Abstract

Objectives

To compare parental attitudes about short stature over time and determine possible factors that predict changes in attitudes.

Study design

At baseline (1993–1994), we surveyed parents about their attitudes regarding their children’s height. We compared parents of children (age 4–15 years) referred to endocrinologists (referred, 154) with those of children with heights <10th percentile seen by pediatricians during regular visits (control, 240). At follow-up (2008–2009), 103 control and 98 referred parents completed a similar survey. We then made a logistic regression analysis to observe changes in perception. Primary variables included self-esteem, treatment by peers and ability to cope with current height.

Results

At baseline, referred parents perceived a worse impact of short stature on their children than did controls. At follow-up, instead, referred parents were 3.8 times more likely to report improvement in self-esteem, 2.4 times more likely to report improved treatment from peers, and 5.7 times more likely to report overall ability to cope with height than were unreferred parents. Perception of psychosocial improvement was greater in the referred than the control group. Referral was a stronger predictor of an improved follow-up response than patients’ current height or change in height.

Conclusion

While incorporating parental attitudes into management decisions, clinicians should be aware that parental perceptions may change over time and that referral itself may lead parents to perceive psychosocial improvements over time.

Keywords: Growth hormone, short stature, ethics

Pediatricians routinely monitor children’s height and weight. If children have short stature, their pediatrician may discuss a referral to an endocrinologist. Decisions about whether or not to refer a child to a specialist, and specialists’ decisions on treatment, are complex. They include consideration of both physiological and non-physiological factors.1 One of the important non-physiological factors is parental concern about the psychological effects of short stature on their child.1,2 Some parents believe that short stature will lead to low self-esteem, poor school performance, or difficulties with peer relationships. These attitudes might influence decisions about starting growth-promoting therapies, administration strategies, and length of the treatment.3 Finkelstein et al showed that physicians were 40% more likely to recommend growth hormone treatment (GH) for a child when the family showed strong interest in the treatment.4

We wondered whether parents who are referred and seek care from a pediatric endocrinologist differ from unreferred parents in their views about short stature. We also wondered how the attitudes about short stature of these two groups of parents change over time. No studies have addressed these questions. To address this gap, we compared attitudes toward short stature among parents of short children referred to endocrinologists for their initial visit and parents of children with heights <10th percentile presenting to their pediatricians for a regular visit who were not referred. Some of the data from the referred cohort have previously been published.4 We then surveyed these same groups of parents (both referred and controls) 15 years later. We asked about their children’s final height and whether or not they had received growth-promoting therapy. Some of the children who were referred at baseline were treated with growth-promoting therapies. Some of the children who were not initially referred eventually started treatment. We also studied which factors predict changes in parental attitudes about short stature from baseline to follow-up.

Methods

In 1993–1994, Feldt et al surveyed the parents of 154 children (ages 4–15 years) who were referred for short stature to any of the 4 pediatric endocrinology practices in the greater Cleveland metropolitan area (referred group). They then surveyed parents of 240 relatively short children (ages 4–15 years) who presented for well-child visits and routine care to pediatricians and family physicians (control group).

The survey was conducted in the participants’ homes by a trained interviewer. The questions were structured as a Likert-type scale (ranking from 1 as “not at all” to 4 as “a lot”) and evaluated how stature affected their child’s feelings, self-esteem, school achievement, social interactions, and overall quality of life. An increase was defined as higher than one point increase on the four point scale.

In 2008–2009, these researchers resurveyed the same parents and compared their retrospective evaluation of the impact of short stature on their children with their initial concerns. They used free and paid search engines to identify 308 of the original parents’ contact information. They surveyed 201 parents whose children had short stature. Of these, 98 had been referred to an endocrinologist for evaluation (referred group) and 103 had not been referred (control group).

The follow-up survey consisted of a brief phone interview. Data gathered included children’s adult height reported by their parents and information about receipt of any growth-promoting therapy (such as testosterone or GH). The parents completed a survey that was almost identical to the original. However, some questions were modified to more appropriately reflect the child’s age. These surveys were scored on the same Likert-type scale as in the original survey. Primary variables therefore once again included self-esteem, treatment by peers and ability to cope with current height.

Finally, to evaluate factors that may predict changes in parental attitudes, we performed a logistic regression analysis and examined parents’ perceptions of improvement from baseline to follow-up for 3 variables: self-esteem, treatment by peers, and ability to cope with current height. We controlled evaluating independent effects, such as referred vs. control, sex (male vs female), current height in standard deviation score (SDs), and change in height in SDs.

This study was approved by the University Hospitals of Cleveland Institutional Review Board for Human Investigation (IRB number: 07–90-135).

Results

At baseline, the rate of survey completion was close to 80%. Children were on average around 9 years old in both groups, as shown in Table. Participants’ height was statistically different (as measured in standard deviation below the mean for their age, <0.001) between the 2 groups. In the referred group, there were considerably more males (69.3%) than females (30.7%).

Table 1.

Baseline (1993–94) and Follow-up (2008–09) Cohorts Characteristics.

| BASELINE | Referred | Control | P value | FOLLOW-UP | Referred | Control | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 154 | 240 | N | 98 | 103 | ||

| Child’s age (years) | 10.3±3.4 | 8.7±3.9 | NS | Received growth therapy (%) | 23.5% | 7.8% | <0.002 |

| Height (SD) | −2.2±0.7 | −1.9±1.0 | <0.001 | Adult Height (SD) | −0.47±0.49 | −0.35±0.41 | NS |

| Father | 171.6±1.8 | 171.2±1.6 | |||||

| Gender (%M/F) | 69.3/30.7 | 57.9/42.1 | <0.01 | Gender (%M/F) | 60.6/39.4 | 55.3/44.7 | <0.01 |

At follow-up, 23.5% in the referred group and 7.8% in the control group reported having received growth-promoting therapy. Among the 98 patients who were referred to endocrinologists, 18 patients received GH, 3 received testosterone, and 75 did not receive any growth-promoting treatment. 2 participants did not provide information about treatment. Among the control patients, 3 reported to have taken GH, 2 testosterone, and 2 lupron. Adult height was comparable between the children in the referred and the unreferred groups, even after controlling for the receipt of growth-promoting therapy. Change in height was also comparable between groups. The sex distribution, although different between groups, was representative of the original cohort.

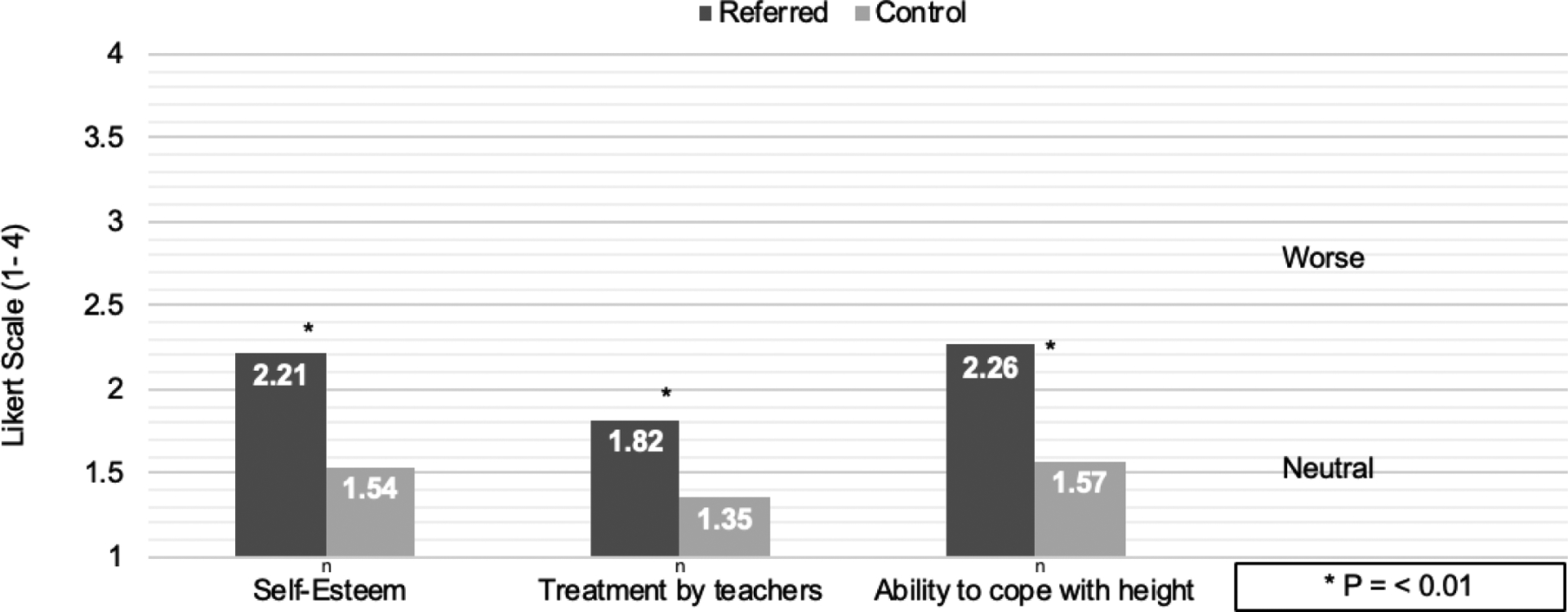

At baseline, referred parents responded to 3 of the 14 questions asked that they perceived greater suffering in their child due to short stature than did parents who were not referred. The answers to 11 questions were not different between the groups and only positive findings are presented in this manuscript. Parental concern was elicited by asking questions that focused on psychosocial problems (self-esteem, treatment by teachers, and overall ability to cope with current height). Those questions were: 1) Does your child’s self-esteem appear to be affected by how he/she feels about his/her height? 2) Does your child notice that he/she is treated differently by teachers because of his/her height? 3) Overall, do you think it is difficult for him/her to cope with his/her current height?

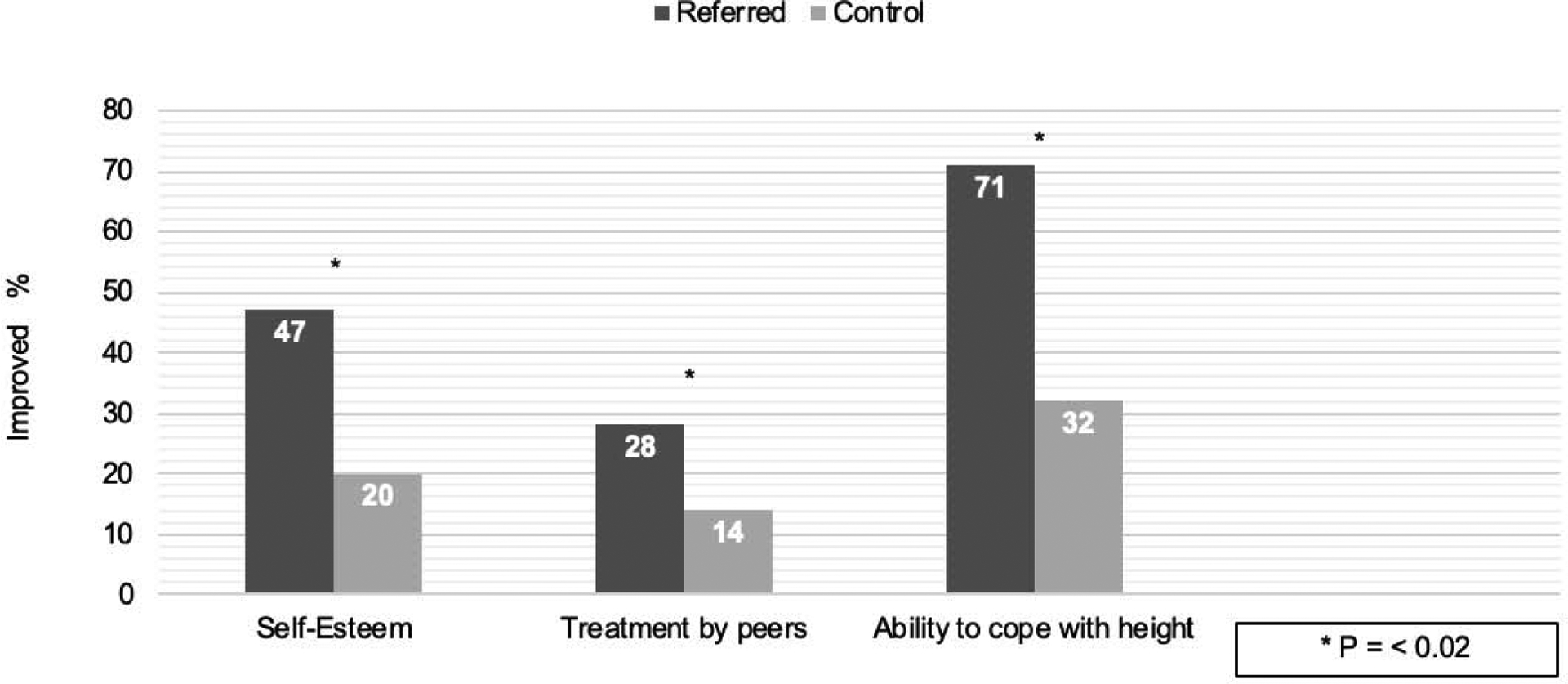

At follow-up, we asked the questions listed above and adjusted the second one to participants’ age (given that children at follow up are on average 24–25 years old): does your child think people treat him/her differently because of his/her height? Measures of self-image, self-esteem, and coping had improved in both groups (Figure 2). Referred parents reported more improvement than did controls. The graph in Figure 2 denotes the same 3 measures as above: improved self-esteem, treatment from peers, and ability to cope with current height. All of these were significantly higher in referred than control groups.

Figure 2.

At follow-up, both groups reported improvement in outcome in the same questions as the original studies. Parents of referred patients were significantly more likely to perceive improvement than were controls.

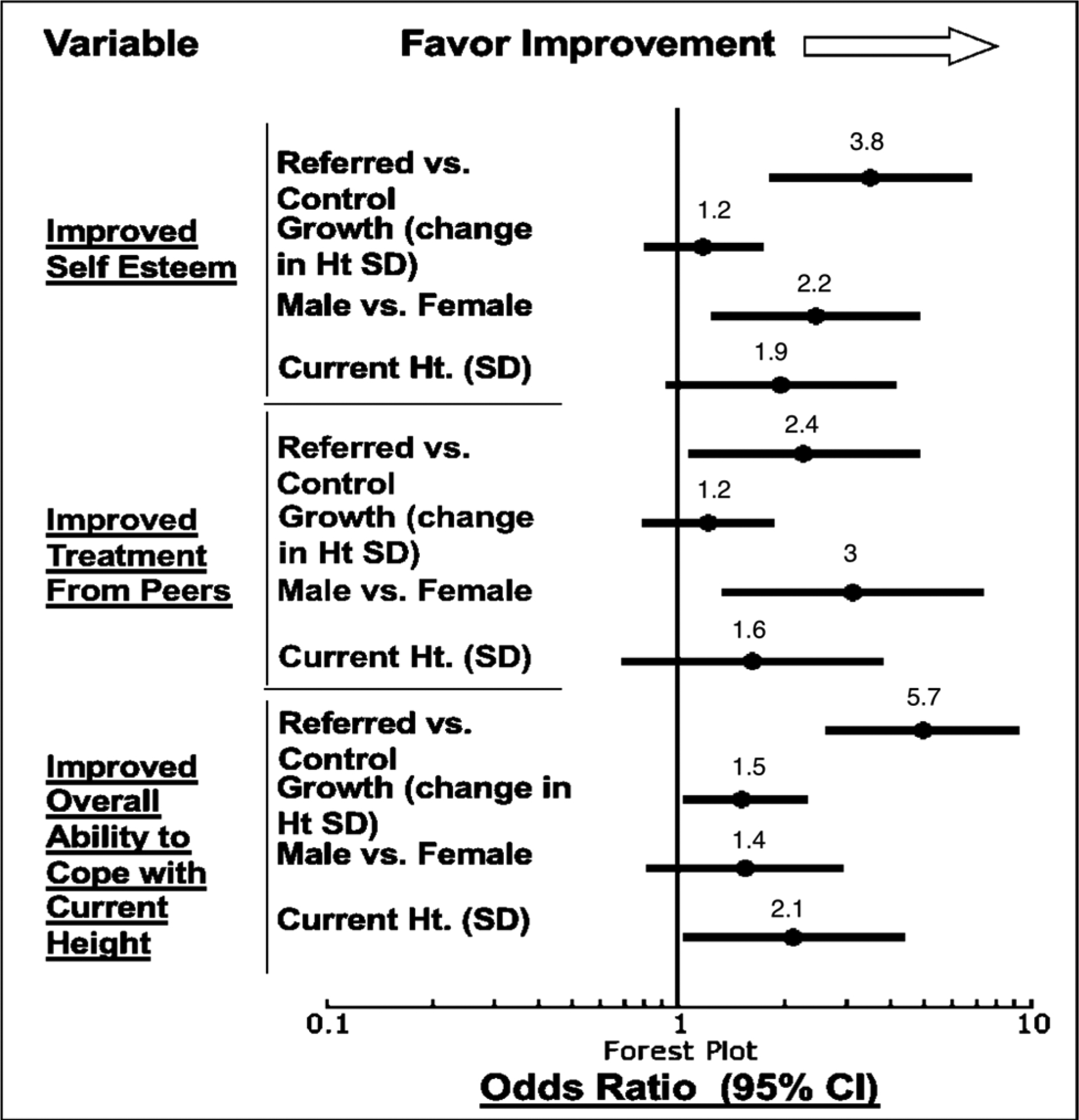

At follow-up, parents whose child was referred to a pediatric endocrinologist were more likely than control parents to believe that their child’s self-esteem had improved, that the child was treated better by peers, and that their child was able to cope with problems that resulted from short stature (Figure 3). Referral to an endocrinologist was a better predictor of psychosocial improvement than was final adult height or change in height since the original study. Being treated was not associated with a perception of fewer psychosocial problems. Untreated control and referred children gained considerably in height SDs over 15 years, reaching similar adult heights.

Figure 3.

Factors predicting change in parental attitudes from baseline to follow-up: Logistic regression. Improvement was associated with referral to endocrinologists in all questions. Male sex was predictive of improved self esteem and perception of treatment from peers. Growth and current height (SD) were predictive of improved ability to cope.

Discussion

One reason why GH treatment is thought to be beneficial for short children is the belief that height is correlated with better psychosocial outcomes. However, there is little evidence that short stature causes psychosocial burdens to children or that GH leads to better psychological outcomes.5,6 Because of this lack of evidence for psychological benefit, the Pediatric Endocrine Society (PES) maintains that although there is supporting evidence for the use of GH for children with severe deficiency of growth hormone or insulin-like growth factor-I, a conservative approach should be used in treatment management of children who have idiopathic short stature or “partial” isolated idiopathic growth hormone deficiency. For these 2 indications, the PES suggests, “Patients and their parents/guardians should be counseled that not starting GH therapy at all is an option”(p. 382).5

In this study, many parents perceived a detrimental psychological impact of short stature on their children. This perception was more likely in children who went on to be referred to endocrinologists than in children of similar height who were not referred. The remarkable finding in this study was that the parents of children who were referred to an endocrinologist were more likely to perceive an improvement in their child’s psychological outcomes than did the parents of children who were not referred, even when controlling for whether the child received treatment or the child’s final adult height; orchange in height since baseline. This was true for measures of self-esteem, treatment by peers, and ability to cope.

Parental attitudes about short stature vary across a wide spectrum. Some parents clearly consider short stature to be a disadvantage and seek treatment for their children.7 Others choose not to seek evaluation or treatment for their child’s short stature. This study suggests that, for at least some parents, referral to an endocrinologist might itself be therapeutic, in as far as being referred to a pediatric endocrinologist was associated with a perception that their child has had a psychosocial improvement. Parental concerns about the detrimental impact of short stature may, in fact, represent parental anxiety about whether they had done everything possible to help their child. That anxiety might be relieved simply by knowing that their child has seen a specialist.

Psychologists have described a phenomenon called the “focusing illusion.”8 This occurs when one focuses on one specific aspect of life to the exclusion of others. This narrowed focus results in overweighting that factor in the experience of well-being. Some parents might be so focused on their child’s short stature that they ignore or downplay other aspects of life that may be psychologically beneficial or detrimental to their child.9,10

This study has limitations. Only 201/394 original participants (51%) participated in the follow-up study. Still, this was 2/3 of the participants for whom we had contact information (201/308). There may have been selection bias in the respondents. We also note that, among the control group, 7.8% of the patients eventually received a form of growth-promoting therapy. This means that children in the control group were referred to some specialists in-between our baseline and follow-up interviews. In spite of these limitations, we believe that the study results suggest some important factors that pediatricians and endocrinologists might consider when counseling parents of children with short stature.

This study provides information to clinicians who wonder how to incorporate parental attitudes into managing decisions about growth promoting therapies. The fact that parents in this study changed their attitudes toward short stature some years after their referral to endocrinologists and the positive impact that referral had on our participants reveal that parental attitudes towards short stature might be more complex than they first appear at initial evaluation. Physicians who may be influenced by parental attitudes in their decisions on treatment should be aware that merely giving parents the chance to talk to a specialist can have a positive outcome in the long term. The results of this study might be complemented by narrative approaches to better understand why parents are concerned about short stature and what might make them change their mind over time.

Figure 1.

At baseline, parental perception of the impact of short stature on their children was worse in the referred group than in the control group. This figure shows the mean values for 3 of the 14 questions asked (self-esteem, treatment by teachers, and overall ability to cope with current height).

Acknowledgments

We thank S. MacLeish, DO, D. Rogers, MD, J.B. Silvers, PhD, and L. Cuttler M.D. for their contributions in primary and secondary data collection, and the Medical Writing Center at Children’s Mercy Kansas City for editing this manuscript.

The data collection part of this study was supported by the NIH(#HD300053). The writing part was funded by the Claire Giannini Fund.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Portions of this study were presented at the Graduate Medical Education Children’s Mercy, May 14, 2019, Kansas City, Mossuri; and at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting, April 24 – May 1, 2019, Baltimore, Maryland.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Maheshwari N, Uli NK, Narasimhan S, Cuttler L. Idiopathic Short Stature: Decision Making in Growth Hormone Use. Indian J Pediatr. 2012; 79:238–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuttler L, Marinova D, Mercer MB, Connors A, Meehan R, Silvers JB. Patient, physician, and consumer drivers: referrals for short stature and access to specialty drugs. Med Care 2009;47:858–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silvers JB, Marinova D, Mercer MB, Connors A, Cuttler L. A national study of physician recommendations to initiate and discontinue growth hormone for short stature. Pediatrics. 2010;126:468–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkelstein BS, Singh J, Silvers JB, Marrero U, Neuhauser D, Cuttler L. Patient Attitudes and Preferences regarding Treatment: GH Therapy for Childhood Short Stature. Hormone Research 1999; 51: 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grimberg A, DiVall SA, Polychronakos C, Allen DB, Cohen LE, Quintos JB et al. Murad on behalf of the Drug and Therapeutics Committee and Ethics Committee of the Pediatric Endocrine Society. Guidelines for Growth Hormone and Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Treatment in Children and Adolescents: Growth Hormone Deficiency, Idiopathic Short Stature, and Primary Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Deficiency. Horm Reseas Paediatr 2016; 86:361–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimberg A, Allen DB. Growth hormone treatment for growth hormone deficiency and idiopathic short stature: new guidelines shaped by the presence and absence of evidence. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 2017; 28:466–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Visser-van Balen H, Sinnema G, Geenen R. Growing up with idiopathic short stature: psychosocial development and hormone treatment; a critical review. Arch Dis Child 2006; 91:433–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandberg D, Gardner M. Short stature is it a psychosocial problem and does changing height matter? Pediatr Clin N Am 2015; 62: 963–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erling A, Wiklund I, Albertsson-Wikland K. Prepubertal children with short stature have a different perception of their well-being and stature than their parents. Quality of Life Research 1994;3:425–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quitmann J, Rohenkohl A, Sommer R, Bullinger M, Silva N. Explaining parent-child (dis)agreement in generic and short stature-specific health-related quality of life reports: do family and social relationships matter? Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2016; 14:150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]