Abstract

The present study investigated the potential of a small molecule inhibitor, 1-deoxynojirimycin (DNJ), to extend the shelf life of tomatoes. The optimum concentration of DNJ and the proper ripening stage for treatment were standardized using response surface methodology, following a central composite design. The concentration of DNJ used for the analysis was 0.15 mM, and 0.30 mM and the ripening stages of the tomato fruit analysed were immature green, mature green, breaker, ripen and over-ripen. Analysis of the influence of the DNJ treatment of the fruit using quadratic multiple regression models considering the factors colour, texture, and free sugars revealed significant responses. A DNJ concentration of 0.30 mM and fruit-ripening stage of mature green was found to be optimal for the treatment. DNJ-treatment maintained fruit firmness throughout ripening with a significant reduction in reducing sugar formation. Enzyme activity of the N-glycan processing enzymes involved in cell wall softening, α-mannosidase and β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase revealed a significant reduction in their activity by 2 and 3.5-fold, respectively. Down-regulation of expression of important ripening-related and softening process-associated genes, aminocyclopropane carboxylic synthase-4, aminocyclopropane carboxylic oxidase, polygalacturonase and pectin methylesterases at 4, 5, 6 and 5-fold, respectively, was also observed. The present results showed that the treatment of mature green tomato fruit with DNJ at a concentration of 0.30 mM can delay the ripening of the tomato fruit by inhibiting cell wall and N-glycan processing enzymes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-020-02196-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Deoxynojirimycin, Response surface methodology, Central composite design, α-Mannosidase, β-N-Acetylhexosaminidase, Tomato

Introduction

Fruit ripening is an essential phase of fruit development where the fruit attains physiological maturity, growth is arrested and the ripening processes begin. During ripening, the nutritional quality of the fruit is enhanced and they achieve the desired colour, sugar level and aroma (Giovannoni 2001; Klee and Giovannoni 2011; Suzuki and Nagata 2019; Zhang et al. 2020).

Enzymes involved in cell degradation soften the cell wall of fruit during ripening (Goulao and Oliveira 2008; Wang et al. 2018). Pectin-methylesterases (PME; EC 3.1.1.11), polygalacturonases (PG; EC3.2.1.15) and galactosidases (EC 3.2.1.23) are known to act on cell wall polymers, causing their degradation and leading to softening of the fruit (Huber et al. 2001; Brummell 2006; Prasanna et al. 2007).

Suppression of these enzymes leads to reduced accumulation of free sugars and diminished damage to the cell wall pectin polymers (Cherian et al. 2014). Various efforts have been made to reduce the fruit softening processes through suppression of genes encoding cell wall degrading enzymes. However, the results were not satisfactory because the targeted enzymes did not influence the texture of fruit (Giovannoni et al. 1989; Giovannoni 2001, 2004; Cherian et al. 2014; Grierson 2016; Verma et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2018).In addition, suppression of the enzymes was not sufficient to stop fruit softening because they were functionally essential components of various other metabolic processes (Brummell and Harpster 2001; Giovannoni 2001, 2004; Saldie et al. 2004).

Meli et al. (2010) used transgenic approaches to show that N-glycan processing enzymes play a fundamental role in the ripening-associated softening processes. Identification of novel compounds that can inhibit N-glycan processing enzymes (NGPEs) such as α-mannosidase, β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase, a-L-arabinofuranosidase, and β-xylosidase, which play a crucial role in the ripening-associated softening processes, could be a relevant target to delay the fruit ripening processes (Martínez et al. 2004; Tateishi et al. 2005; Meli et al. 2010). There are 10 N-glycan processing enzymes, among which α-mannosidase and β-N-acetylhexosaminidase are the most important in relation to fruit ripening (Priem et al. 1993). α-mannosidase cleaves the terminal mannosidic linkages and β-N-acetylhexosaminidase cleaves terminal sides of hexose aminidase linkages of high-mannose and complex types of the N-glycoproteins present in the plant cell wall. Higher expression of these two enzymes causes excessive softening and a reduction in their activity maintains the firmness of the fruit (Ghosh et al. 2011; Meli et al. 2010). Silencing of α-mannosidase and β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase genes extended the shelf-life of tomato fruit up to 45 days, while cell wall disassembly and deterioration of control fruit occurred within 20 days (Meli et al. 2010; Ghosh et al. 2011; Irfan et al. 2016). Inhibition of the N-glycan processing enzymes through non-transgenic methods, such as coating and dipping treatments, made it possible to extend the shelf-life of fruit (Lin and Zhao 2007; Nawab et al. 2017; Chaturvedi et al. 2019).

Several potent N-glycan processing enzyme inhibitors have been reported in animal cell culture models, including castanospermine, swainsonine, kifunensine, tunicamycin, deoxymannojirmycin, deoxynojirimycin, fagomine and isofagomine (Butters et al. 2009; Gloster and Vocadlo 2012). The present work focused on 1-deoxynojirimycin (DNJ), an alkaloid iminosugar, popularly known as moranoline (Supplementary Figure. 1), which is a derivative of polyhydroxylated piperidines. Iminosugars contain an analogue of the six-membered glucose ring structure in which an amino group replaces the oxygen group.DNJ is present in microorganisms such as Bacillus spp., Streptomyces spp.as well as in many plant species like mulberry (Hardick et al. 1991; Shibano et al. 2004).DNJ is known to have anti-diabetic, anti-obesity, anti-inflammatory, and anti-atherosclerosis as well as antioxidant properties and is a potent inhibitor of α-glucosidase (Norez et al. 2006; Kumar et al. 2011; Kiappes et al. 2018). However, so far, the mode of action and its use in delaying fruit ripening as an edible fruit coating has not been evaluated.

Response surface methodology (RSM), can be used to optimise process conditions and determine the effect of different factors and their interactions on the response variable (Thompson 1982; Myers and Montgomery 1995). It has been successfully used to optimise the composition and concentration of volatiles in grape berries during ripening (Torchio et al. 2016), for metabolite profiling of kiwifruit (Lim et al. 2017), for studying the physicochemical and nutritional characteristics of banana flour processing (Campuzano et al. 2018) and for optimisation of extraction conditions for improving the phenolic content of Berberisasiatica fruit (Belwal et al. 2016).In this study, we used DNJ to delay fruit ripening in tomato fruit and optimised the DNJ concentration using an RSM approach as well as studied the physiology of the delay in fruit ripening.

Materials and methods

Plant material, fruit treatment, and storage condition

Tomato (‘Pusa Hybrid 1’) were grown in Mysuru, Karnataka, India, and fruit harvested at 70–80 days after flowering. The harvested fruit was divided into five categories according to their maturity stage: immature green, mature green, breaker, ripen and over-ripen (Wang et al. 2009; Moniruzzaman et al. 2013; Skolik et al. 2019) (Fig. 1a). The fruit was surface sterilised with 2% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite for 1 min, washed thrice with distilled water and air-dried at room temperature. The fruit was selected randomly for different treatments. The treatment groups were: control (distilled water with 0.1% Tween 20) as well as 0.30 mM and 0.15 mM 1-deoxynojirimycin (08012) from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) with 0.1% Tween 20 in distilled water, applied by dipping the fruit (5 fruit/L) for 30 min. The fruit was allowed to dry at room temperature and then divided into three replications, each with five fruit. Each replication was placed in perforated polyethylene packaging bags and stored for up to 15 days at 25 °C and 60% relative humidity (RH). On day 15, samples were analysed, weighed and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for further analyses.

Fig. 1.

a Different stages of fruit development; immature green, mature green, breaker, ripen and overripe; b effect of the deoxynojirimycin (DNJ) treatment on the ripening of tomato fruit after 15 days. Fruit treated with DNJ significantly retained the textural quality and delayed colour change to red of the fruit as is evident from the figure

Optimisation of the DNJ-treatment by response surface methodology (RSM)

For optimising the DNJ-treatment, a face-centered central composite design was selected (Belwal et al. 2016; Myers and Montgomery 1995). The input variables chosen for the analysis were the concentration of the DNJ and the fruit developmental stage. The tomato fruit maturation and ripening comprise various stages of development, which can be divided into five phases: the immature green, mature green, breaker, ripen and over-ripen stages. For selecting the phase of the fruit to be treated with DNJ to attain the delayed ripening, it is necessary to assign values when designing the RSM model. Values for the ripening stage were assigned based on the development stage of the fruit, where values one, two, three, four and five designate immature green, mature green, breaker, ripen and over-ripen stages of the fruit, respectively (Fig. 1a).In the present experiment, the following fruit phases after harvest were included: mature green, breaker and ripening stages. Immature green fruit was excluded as they were not harvested at this stage and the over-ripen fruit was also omitted as fruit at this stage is not usually considered for consumption and fruit development has progressed so far that the processes are irreversible.

The experiment for the optimisation was designed and analysed using the Minitab statistical software version 17 (Minitab Inc., State College, PA, USA). For the RSM design and analysis, the combined effect of two independent variables (DNJ concentration and fruit harvesting stage, coded as X1 and X2, respectively) was employed. The minimum and maximum values for the fruit ripening stage were set to two and four (denoting mature green and ripen stages) and for DNJ concentration, the values were set to 0 and five (0–0.30 mM). The complete design consisted of 13 combinations, including five replications of the center point (Table 1). The responses measured were the fruit texture (Texture), red colour development (Chroma) and free sugar content (Sugar).

Table 1.

Central composite experimental design for the DNJ treatment and observed physiochemical response sat different ripening stages of tomato fruits during storage time

| Run | Factor | Response | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNJ concentration (mg/100 mL) | Fruit ripening stage | Texture (N) | Chroma (L*a*b*) | Sugar (%) | |

| 1 | 0.0 | 2 | 49.8550 | 49.6204 | 33.54 |

| 2 | 5.0 | 2 | 56.4562 | 47.5508 | 19.59 |

| 3 | 0.0 | 4 | 47.9739 | 50.9221 | 34.65 |

| 4 | 5.0 | 4 | 53.7849 | 47.5701 | 22.23 |

| 5 | 0.0 | 3 | 47.2218 | 53.2655 | 34.19 |

| 6 | 5.0 | 3 | 55.4887 | 47.3797 | 19.90 |

| 7 | 2.5 | 2 | 54.0647 | 51.8738 | 20.49 |

| 8 | 2.5 | 4 | 54.0786 | 49.8811 | 21.09 |

| 9 | 2.5 | 3 | 51.8487 | 49.2363 | 19.98 |

| 10 | 2.5 | 3 | 53.1248 | 48.9778 | 18.84 |

| 11 | 2.5 | 3 | 51.6955 | 48.0439 | 19.46 |

| 12 | 2.5 | 3 | 52.2303 | 47.6232 | 18.93 |

| 13 | 2.5 | 3 | 52.1130 | 49.1830 | 18.96 |

The tomato fruit was dip-treated with different concentrations of deoxynojirimycin (DNJ) and samples collected at 15 days for analysing the changes in the fruit texture, colour and reducing sugar content. The ripening stages numbered as two, three and four correspond to the mature green, breaker and ripened stages of the tomato fruit ripening phases, respectively. The texture strength shown is the applied force in Newton (N), colour as the L*a*b* values and free sugar content as the percentage (%) of actual content in the samples

Texture analysis

The firmness of each biological replication of fruit was measured at the end of each storage time using a Universal Testing Machine (UTM Lloyds, LR—5 K, Lloyd Instruments Ltd., Fareham, U.K.). The instrument applies a compression load of 10 mm per min. Shear was the parameter used to analyse the firmness of the fruit. A shear probe with a diameter of 2 mm was made to cut the fruit at a constant jog speed to a depth of 50 mm per min with a load of 0.5 N (N) (Candir et al. 2017; Li et al. 2017; Cheema et al. 2018). The maximum force applied to break the fruit peel represents the hardness, which was expressed in Newton as reported by Breene (1975).

Colour analysis

Tomato fruit surface colour of each biological replication was measured using Hunter Lab Color Measuring System (Minolta CM3500D) at visible wavelengths of light, following a previously reported method (McGuire 1992; Candir et al. 2017) with the colour space of L*, a*, and b*, indicating lightness, red/green colour, and blue/yellow colour, respectively. C* values (Chroma) were calculated from the a* and b* values. The C* values were calculated as (a*2 + b*2) × 0.5.

Estimation of reducing sugars by the acid (DNS) method

The pericarp of fresh fruit (1 g) was homogenised in 5 mL of 100 mM sodium phosphate extraction buffer (pH 6.6), centrifuged at 9000 × g for 15 min and the supernatants were collected. The supernatant(1 mL) was made up of 3 mL with distilled water and then 3 mL DNS solution (1% v/v) was added and mixed thoroughly (Miller 1959). The reaction mixture was kept in a boiling water bath for 5 min. After the colour developed, 1 mL 40% (w/v) potassium sodium tartrate tetrahydrate was added and the solution mixed. The experimental tubes were allowed to cool and the absorbance was measured at 510 nm using a NanoQuantplate reader (Tecan-Infinite pro-M 200, Austria). Galactose, 0.1–1 mg/mL, was used to prepare a standard curve.

Activity assay for α-mannosidase and β-D-N-acetylhexosaminidase

One gram of pericarp tissue was ground in liquid nitrogen, suspended in 5 mL of 100 mM sodium phosphate extraction buffer (pH 6.6), containing a final concentration of 0.25 M sodium chloride and 1 mM phenyl methane sulfonyl fluoride. The mixture was incubated for overnight extraction in a shaker at 100 rpm at 4 °C. Extracted tomato samples were centrifuged at 9,072 × g for 20 min and the supernatant was used for further analysis (Meli et al. 2010).

The reaction mixture consisted of 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.5) for α-mannosidase and 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) for β-D-N-acetylhexosaminidase. The substrate was 3 mM p-nitrophenyl-α-D-mannopyranoside for α-mannosidase and 3 mM p-nitrophenyl-β-D-N-acetylglucosaminide for β-D-N-acetylhexosaminidase. The activity was measured after terminating the reaction by adding 0.5 M sodium carbonate. The colour developed was recorded at 405 nm using a NanoQuant plate reader (Tecan-Infinite pro-M 200, Austria) and the amount of p-nitrophenol (PNP) released was determined using a standard curve. A unit of the enzyme is defined as the amount of enzyme required to liberate one μmol of p-nitrophenol per min of a reaction. The specific activity was calculated as enzyme units per mg protein. Protein content was calculated from a bovine serum albumin (BSA) standard curve using the Bradford protein assay method (Bradford 1976).

RNA extraction, primer designing, and gene expression analysis by qPCR

RNA from the treated tomato was isolated according to the TRIzol phenol-chloroform protocol Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). One gram of fruit sample was taken for the RNA extraction. The sample was flash-frozen by adding liquid nitrogen, ground to powder and then the TRI reagent was added. After isolation, RNA was quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (NP1000, Thermo Fischer, Delaware, USA). One microgram of RNA was used for cDNA synthesis using the Iscript cDNA synthesis kit (Biorad, 708,891) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Gene-specific tomato primers were designed using the NCBI-Primer-BLAST software (Supplementary Figure. 1b) and qPCR studies were carried using One-step real-time qPCR (AppliedBiosystemsQuantStudio5, Singapore) using PowerUp SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems, A25742). The PCR cycle comprised an initial denaturation (95°Cfor 5 min) followed by 40 cycles of denaturation (95 °C for 30 s), annealing (52 °C for 30 s) and extension (72 °C for 30 s). The analysis was carried out in triplicate. Changes in gene expression data were calculated as fold changes, normalised to the endogenous reference gene actin and set relative to the control treatment by the 2ΔΔct method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001).

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were carried out in triplicate. Biological replications were individual fruit from different plants. Experimental values were analysed using GraphPad Prism 5 statistical software (San Diego, CA, USA). Data were subjected to one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison Test to determine significant differences among samples and P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results and discussion

Model fitting and analyses of response surface modeling

DNJ is a bioactive molecule, well-established in cell culture studies, where it is known to inhibit N-glycan processing enzymes such as glycosidase and α-glucosidase enzymes. Furthermore, it is also known as an anti-diabetic molecule(Kimura et al. 2004; Kiappes et al. 2018). In plants, N-glycan processing enzymes are involved in ripening-related cell wall softening in fruit as well. However, there is limited information on the effect of DNJ in plant systems. We are the first to report that DNJ is a potent inhibitor of cell wall degrading enzymes and to study its role in delaying the ripening of tomato fruit using response surface methodology.

The central composite experimental design (CCD) for the DNJ-treatment was performed by considering two independent variables, X1 and X2, where X1 denotes the concentration of DNJ and X2 denote stages of tomato fruit ripening. The observed responses are shown in Table 1. The results from the analyses of texture, colour development and sugar accumulation during fruit ripening were fitted into a second-order polynomial equation. Regression coefficient values were also estimated and explained in Table 2. The regression equations for the responses were derived from the experimental values and are as follows:

Table 2.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the delayed fruit ripening responses; texture, chroma and reducing sugar content as a function concentration of fruit (X1) and ripening stage of DNJ (X2)

| Factors | Adjusted mean square | F value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Texturea | |||

| X1 | 1.9957 | 2.58 | 0.152 |

| X2 | 0.7530 | 0.97 | 0.356 |

| X1 × X1 | 5.6469 | 7.31 | 0.031 |

| X2 × X2 | 4.5714 | 5.91 | 0.045 |

| X1 × X2 | 0.1561 | 0.20 | 0.667 |

| Error (lack-of-fit) | 1.3895 | 4.48 | 0.091 |

| Chromab | |||

| X1 | 0.38708 | 0.16 | 0.703 |

| X2 | 0.47699 | 0.19 | 0.672 |

| X1 × X1 | 0.01084 | 0.00 | 0.949 |

| X2 × X2 | 0.617 | 0.27 | 0.617 |

| X1 × X2 | 0.41105 | 0.17 | 0.694 |

| Error (lack-of-fit) | 5.00081 | 9.30 | 0.028 |

| Sugarc | |||

| X1 | 103.185 | 266.39 | 0.000 |

| X2 | 1.451 | 3.75 | 0.094 |

| X1 × X1 | 146.404 | 377.97 | 0.000 |

| X2 × X2 | 2.906 | 7.50 | 0.029 |

| X1 × X2 | 0.585 | 1.51 | 0.259 |

| Error (lack-of-fit) | 0.594 | 2.55 | 0.194 |

The variables X1 and X2 denote the factors ‘concentration’ and ‘ripening stage’, respectively

aThe correlation coefficient (r2) the Texture model is 0.93

bThe correlation coefficient (r2) the Chroma model is 0.56

cThe correlation coefficient (r2) the Sugar model is 0.99

The regression equation for texture:

Texture = 60.75 + 2.760 X1—8.28 X2—0.2288 X1 × X1 + 1.287 X2 × X2—0.079 X1 × X2.

The regression equation for chroma:

Chroma = 54.75—0.32 X1—2.74 X2—0.010 X1 × X1 + 0.492 X2 × X2—0.128 X1 × X2.

The regression equation for sugar content:

Sugar = 41.65—8.994 X1—5.81 X2 + 1.1649 X1 × X1 + 1.026 X2 × X2 + 0.153 X1 × X2.

The obtained values for correlation coefficients (r2) were 0.93 for the texture model, 0.56 for the chroma model and 0.99 for the sugar model. The statistical analyses of the values showed that the present treatment had a significant effect on free sugar and texture of the fruit, but not for the fruit colour (chroma). The error (lack-of-fit) values obtained for each response indicates whether the treatment factors had any influence on a response. A significant error (lack-of-fit) value shows that the response observed is not significantly influenced by the treatment. The chroma model showed an error (lack-of-fit) P value of 0.028, implying that the treatment had no significant effect on the colour development of the fruit during ripening. However, error (lack-of-fit) P values for texture and sugar were 0.091–0.194, respectively, implying that there was a significant influence by the treatment on the texture as well as on the sugar content of the tomato fruit during ripening.

Analyses of response surface plot

Graph plotting of the effects of the two variables, the concentration of DNJ (X1) and ripening stage (X2), using the response surface 3D modeling on the three factors texture, chroma, and sugar content of the fruit is shown in (Fig. 2a–c.) To determine the quality of stored tomato fruit, DNJ-treated tomato fruit was sampled on day 15 after treatment and their texture analysed. The results are plotted against DNJ-concentration at different ripening stages (Fig. 2a). DNJ-treated fruit maintained its structure throughout the experiment, showing retention of firmness, whereas control fruit lost their rigidity and started deteriorating (Fig. 1b). This indicates enzymatic cell wall degradation and there are reports suggesting that specific enzymes such as α-mannosidase, β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase, polygalacturonase and pectin methylesterase can act on the cell wall of fruit. Overexpression of these enzymes leads to excessive softening, whereas inhibiting them gives firmness to the fruit (Yang and Hoffman 1984; Giovannoni et al. 1989; Zhang et al. 2009; Ghosh et al. 2011; Irfan et al. 2016). As the concentration of DNJ increased, it inhibited the activity of cell wall degrading enzymes, which actively affected texture during the ripening of the fruit. This resulted in the extension of shelf-life of the fruit and maintained firmness as well. Hence, DNJ effectively influences texture and results in the desired quality of fruit after long-term storage.

Fig. 2.

Response surface plot and optimisation of the factors affecting the tomato fruit ripening responses. a Surface plot of the combined effect of DNJ concentration and ripening stage on texture; b chroma and; c sugar content of the fruit. Chroma is indicated by the red colour development and sugar indicates reducible sugar formation; d the optimisation of the factors to attain the maximum desired responses where the fruit after treatment will result in a slower change in red colour (chroma), retain the structure characteristics (texture) and less development of reducible sugars. A DNJ concentration of 4.84 mg/100 mL (0.30 mM) and fruit ripening stage two (mature green) was the optimum conditions for treatment

Chroma indicates red colour development during the ripening processes. As the ripening starts, chlorophyll degradation in the fruit begins and the synthesis of lycopene, carotenoids and anthocyanins results in the red colouration of tomato fruit (Giovannoni 2001; Klee and Giovannoni 2011; Cherian et al. 2014; Candir et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2019). Colour is a vital attribute visually to determine the quality of fruit when they start ripening. In our study, the response surface methodology (RSM) plot showed that the concentration of DNJ delayed the development of the red colour of the fruit (Figs. 1b, 2b). This indicates that there was a delayed degradation of chlorophyll during ripening because of the inhibitory action of DNJ.

Sugar content indicates the formation of reducible sugars during fruit ripening. It has been reported that metabolic changes occur during maturation of climacteric fruits, resulting in increased accumulation of free sugars (Klee and Giovannoni 2011). Fruit cell walls are mainly composed of starch, cellulose, hemicellulose and pectin molecules and these molecules will be degraded by cell wall degrading enzymes, resulting in the accumulation of sugars (Hulme 1971; Giovannoni 2001; Klee and Giovannoni 2011; Cherian et al. 2014). In the present study, the fruit was analysed for reducing sugar content and results are represented in an RSM 3D graph. There was a reduction in the formation of reducing sugars in the DNJ-treated fruit. As the concentration of DNJ increased, we observed that the accumulation of free sugar was reduced. On the other hand, an increase in the free sugar content was observed in the control fruit (Fig. 2c). Hence, there was reduced degradation of cell wall polymers due to the inhibitory action of DNJ on cell wall enzymes. DNJ effectively inhibits the cell wall enzymes, which are responsible for the formation of free sugars in the cell walls during the ripening of tomato fruit.

Optimisation and verification of response surface 3D plot

Optimisation of the treatment conditions predicted that a DNJ concentration of 0.30 mM gave the maximum response in delaying fruit ripening. The fruit ripening stage of 2.0 (mature green) was optimal for the treatment among the different ripening stages of tomato fruit (Fig. 2d).

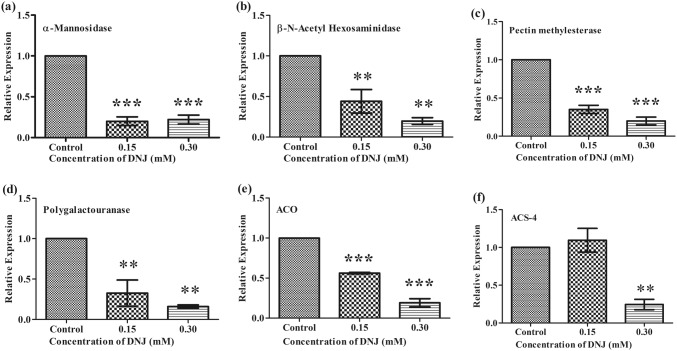

To analyse the role of other ripening-related factors influenced by DNJ, tomato fruit at the mature green stage was treated with 0.30 mM DNJ (50 mg/L) by dipping. Expression analysis by qPCR of the genes coding for the cell wall degrading enzymes α-mannosidase and β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase also showed that the optimum DNJ-treatment could significantly down-regulate these enzymes. Gene expression analysis of the selected ripening-related, cell wall-degrading enzymes (N-glycan processing enzymes and other pectin cleaving enzymes) were also carried out after the DNJ-treatment. DNJ-treatment significantly down-regulated the expression of these genes during tomato fruit ripening as well. (Fig. 4) The treatment conditions optimised by the RSM matched with results obtained in the analysis at the gene expression and enzyme levels as well.

Fig. 4.

Relative gene expression of cell wall-associated genes during fruit ripening after DNJ-treatment of tomato fruit. Relative expression of a α-Mannosidase; b β-N-Acetylhexosaminidase; c Pectin methylesterase; d Polygalacturonase; e Aminocyclopropane carboxylic oxidase; f Aminocyclopropane carboxylic synthase-4 analysed by qPCR. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM for triplicate determinations. The gene expression values of the DNJ-treated fruit were normalised with respect to the control fruit using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001 compared to the control

α-Mannosidase and β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase regulate tomato fruit ripening

The mechanisms behind the fruit softening processes were assessed by studying whether the activities of enzymes during ripening correlated with the observed cell wall changes in the fruit. α-mannosidase and β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase are carbohydrate hydrolases playing a pivotal role in the ripening-associated softening processes and their activities are higher during the later stages of fruit ripening. Degradation of fruit cell walls by these two enzymes starts at the middle stages of fruit ripening,i.e. at the breaker and ripen stages (Yang and Hoffman 1984; Alexander and Grierson 2002; Meli et al. 2010). These enzymes also influence other biochemical changes during ripening, like the accumulation of free sugars and the enhancement of the activity of N-glycan processing enzymes.

We used two substrates to study the specific activity of α-mannosidase and β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase. Thus, p-nitrophenyl-α-d-mannopyranoside (pNP-Man) and p-nitrophenyl- β-d-N-acetylglucosaminide (pNP-GlcNAc) were used as the substrates, respectively. We studied the effect of DNJ on the mature green stage of tomato fruit according to the RSM optimisation studies. Higher activities of α-mannosidase and β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase were found in the control fruit, compared to the DNJ-treated tomato fruit (Fig. 3). The DNJ treatment effectively down-regulated the activity of α-mannosidase and β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase during ripening, resulting in delayed tomato ripening.

Fig. 3.

The specific activity of sugar reducing enzymes from the pericarp of tomato fruit treated with deoxynojirimycin (DNJ): a α-Mannosidase and; b β-N Acetylhexosaminidase, represented as µmol p-nitrophenol released/min/mg of protein. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM for triplicate determinations. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001 compared to the control

Previous reports showed that gene silencing of α-mannosidase and β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase extended the shelf-life of fruit up to 45 days (Meli et al. 2010). However, we followed a non-GMO approach to delay the ripening process of climacteric fruit. Our experiments with DNJ showed that effective inhibition of N-glycan processing enzymes could result in the extension of the shelf-life of tomato fruit. Together, these observations show that α-mannosidase starts to act on the N-glycoprotein complex and high mannose types present in the tomato cell wall. The specific activity of α-mannosidase was significantly reduced by DNJ. β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase plays a similar role in ripening-associated softening processes. Thus, this enzyme also cleaves two types of N-glycoprotein, resulting in the accumulation of N-glycans and thus fruit ripening. We observed that DNJ suppresses the β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase activity.

Gene expression analysis of cell wall genes during tomato fruit ripening after DNJ treatment

The expression of the ripening-related genes was quantified after harvesting of tomato fruit at day 15 after DNJ-treatment. The ripening-related fruit cell wall softening genes, α-mannosidase, β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase, polygalacturonase, pectin methylesterase, 1-aminocyclopropane 1-carboxylic oxidase, and 1-aminocyclopropane 1-carboxylic synthase were selected for the gene expression analysis as they are reported to play a significant role in climacteric fruit ripening (Giovannoni 2004; Goulao and Oliveira 2008; Meli et al. 2010; Ghosh et al. 2011). The analyses showed that the expression of the α-mannosidase gene in tomato fruit was significantly down-regulated after treatment with the two concentrations of DNJ (Fig. 4a). β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase is another N-glycan processing enzyme, which cleaves the terminal N-glycoprotein linkages present in the fruit cell wall and the gene coding for this enzyme was also significantly down-regulated in the fruit treated with DNJ when compared with control fruit (Fig. 4b). Thus, DNJ-treatment is an effective treatment to reduce expression of genes involved in the ripening process and the treatment also down-regulated the expression of other cell wall degrading genes like pectin methylesterase and polygalacturonase (Fig. 4c, d).

Ripening is a phenomenon where many genes are actively involved. However, only a few genes play a role in the ripening-associated softening processes, mainly the N-glycan processing enzymes, which cleave the terminal glycoproteins (Martínez et al. 2004; Tateishi et al. 2005; Meli et al. 2010; Ghosh et al. 2011). α-mannosidase and β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase play essential roles in fruit ripening and silencing of these genes using a gene knock-down approach resulted in delayed tomato fruit ripening and extension of shelf-life (Meli et al. 2010; Ghosh et al. 2011; Irfan et al. 2016). The involvement of other N-glycan processing enzymes in ripening has also been shown, e.g., in Japanese pear and strawberry fruit (Tateishi et al. 2005).

Genes involved in cell wall pectin degradation are also involved in the fruit ripening process. An increase in the expression level of these genes affects the cell wall decomposition and loosening of the cell wall, leading to the softening of the fruit (Pressey and Avants 1977; Tucker and Grierson 1982; Giovannoni et al. 1989). To obtain the desired quality fruit with optimum firmness, targeting genes involved in cell wall degradation is also essential. For example, the enzymes polygalacturonase (PG) and pectin methylesterase (PME) play important roles in fruit ripening (Smith et al. 1990; Tieman et al. 1992). In the current study, the expression of pectin methylesterase was down-regulated during ripening in DNJ-treated compared with control fruit (Fig. 4c). Expression of PG was also down-regulated by DNJ-treatment and the changes in expression were significantly correlated with the concentration of DNJ. The GMO approach of antisense technology has been used to inhibit the cell wall pectin associated genes and silencing PG genes resulted in delayed ripening (Pressey and Avants 1977; Tucker and Grierson 1982; Giovannoni et al. 1989; Smith et al. 1990). However, we succeeded in delaying the ripening of tomato fruit using DNJ, regulating cell wall pectin degradative genes at the gene expression level by indirect regulation of the pathways they control.

Regulation of genes involved in fruit ripening is a challenging process. Blocking of ethylene and ethylene biosynthetic genes along with cell wall genes may give an extension of the shelf-life of fruit. In tomatoes, ethylene plays different roles during different developmental stages up to maturation. At the breaker stages of fruit, ethylene production will be high, reaching the maximum level and inducing ripening (Alexander and Grierson 2002). There are two ethylene biosynthetic genes, which are primarily responsible for the production of ethylene, namely 1-aminocyclopropane 1-carboxylic oxidase (ACO) and1-aminocyclopropane 1-carboxylic synthase (ACS4), both of which have multiple isoforms (Lincoln et al. 1993). Blocking of ACO and ACS4 controls the production of ethylene, resulting in the enhancement of shelf-life of tomato fruit (Yang and Hoffman 1984; Alexander and Grierson 2002; Zhang et al. 2009). We found that after DNJ-treatment, the expression level of ACO declined compared with the control fruit (Fig. 4e). ACS4 gene expression was up-regulated at the lower (0.15 mM) concentration of DNJ, but down-regulated at the higher concentration (0.30 mM). This suggests that DNJ may not be sufficient to suppress the activity of the ACS4 gene at the low concentration (Fig. 4f). When the concentration of DNJ increased to 0.30 mM, the gene expression level decreased, indicating that this concentration could enhance the shelf-life of tomato fruit.

Leaves of mulberry (Commelina communis) has been reported as a particularly rich source of DNJ and also some bacterial strains (Bacillusspp. and Streptomyces spp.) have been found as important sources (Gao et al. 2016). The yield of the DNJ can be further enhanced from mulberry leaves by fermentation with microorganisms, such as Lactobacillus plantarum (lactic acid bacteria), Zygosaccharomyces rouxii (yeast), Wickerhamomyces anomalus (yeast) and Bacillus subtilis (Gao et al. 2016). Currently, the synthesis of DNJ is achieved by synthetic strategies and fermentation by various Bacillus or Streptomyces species. The present report of the potential of DNJ to delay the ripening of a highly perishable fruit such as tomato is an important observation and there are prospects that a natural source can be developed into a commercial project that can gain wider use in preserving the fruit quality in tomato and potentially other perishable fruits.

Conclusion

We report, for the first time, the application of DNJ and its effect on ripening in tomato. The optimisation of DNJ concentration and ripening stage for treatments to delay tomato fruit ripening was achieved using the RSM approach. The theoretical model was validated and we found that it fitted well with subsequent experimental values. The correlation coefficient between texture and sugar was 0.92, which shows the adequacy of the model. DNJ at 0.30 mM was the optimised concentration and the green stage of tomato fruit development was the appropriate time to give the treatment for extending the shelf-life. Analyses of cell wall degrading enzymes supported the optimisation of the treatment conditions for the delayed fruit ripening. This information will help enable us to design DNJ formulations that can be used to treat other climacteric and non-climacteric fruit, also to avoid textural softening and enhance the shelf-life of essential crops. Textural softening of fruit is affected by N-glycan processing enzymes and DNJ inhibited N-glycan processing enzymes and other genes coding for cell wall degrading enzymes, as well as ethylene biosynthetic genes.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Director of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, the Central Food Technological Research Institute, for providing all the facilities for the work. We also wish to thank UGC-RGNF for financial support.

Author contribution

NPS conceived and designed the experiments. DD, BP, and NPS performed the experiments and analysed the data. DD and NPS wrote and edited the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alexander L, Grierson D. Ethylene biosynthesis and action in tomato: a model for climacteric fruit ripening. J Exp Bot. 2002;53:2039–2055. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erf072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belwal T, Dhyani P, Bhatt ID, et al. Optimization extraction conditions for improving phenolic content and antioxidant activity in Berberis asiatica fruits using response surface methodology (RSM) Food Chem. 2016;207:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.03.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breene WM. Application of texture profile analysis to instrumental food texture evaluation. J Texture Stud. 1975;6:53–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4603.1975.tb01118.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brummell DS. Primary cell wall metabolism during fruit ripening. NZ J Forest Sci. 2006;36:99. [Google Scholar]

- Brummell DA, Harpster MH. Plant cell walls. Dordrecht: Springer; 2001. Cell wall metabolism in fruit softening and quality and its manipulation in transgenic plants; pp. 311–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butters TD, Alonzi DS, Kukushkin NV, et al. Novel mannosidase inhibitors probe glycoprotein degradation pathways in cells. Glycoconj J. 2009;26:1109. doi: 10.1007/s10719-009-9231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campuzano A, Rosell CM, Cornejo F. Physicochemical and nutritional characteristics of banana flour during ripening. Food Chem. 2018;256:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.02.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candir E, Candir A, Sen F. Effects of aminoethoxyvinylglycine treatment by vacuum infiltration method on postharvest storage and shelf life of tomato fruit. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2017;125:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2016.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi K, Sharma N, Yadav SK. Composite edible coatings from commercial pectin, corn flour and beetroot powder minimize post-harvest decay, reduces ripening and improves sensory liking of tomatoes. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;133:284–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.04.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheema A, Padmanabhan P, Amer A, et al. Postharvest hexanal vapor treatment delays ripening and enhances shelf life of greenhouse grown sweet bell pepper (Capsicum annum L.) Postharvest Biol Technol. 2018;136:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2017.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cherian S, Figueroa CR, Nair H. ‘Movers and shakers’ in the regulation of fruit ripening: a cross-dissection of climacteric versus non-climacteric fruit. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:4705–4722. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao K, Zheng C, Wang T, et al. 1-Deoxynojirimycin: Occurrence, extraction, chemistry, oral pharmacokinetics, biological activities and in silico target fishing. Molecules. 2016;21:1600. doi: 10.3390/molecules21111600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Meli VS, Kumar A, et al. The N-glycan processing enzymes α-mannosidase and β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase are involved in ripening-associated softening in the non-climacteric fruits of capsicum. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:571–582. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni J. Molecular biology of fruit maturation and ripening. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2001;52:725–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni JJ. Genetic regulation of fruit development and ripening. Plant Cell. 2004;16:S170–S180. doi: 10.1105/tpc.019158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni JJ, DellaPenna D, Bennett AB, Fischer RL. Expression of a chimeric polygalacturonase gene in transgenic rin (ripening inhibitor) tomato fruit results in polyuronide degradation but not fruit softening. Plant Cell. 1989;1:53–63. doi: 10.1105/tpc.1.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloster TM, Vocadlo DJ. Developing inhibitors of glycan processing enzymes as tools for enabling glycobiology. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:683–694. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulao L, Oliveira C. Cell wall modifications during fruit ripening: when a fruit is not the fruit. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2008;19:4–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2007.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grierson D. Identifying and silencing tomato ripening genes with antisense genes. Plant Biotechnol J. 2016;14:835–838. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardick DJ, Hutchinson DW, Trew SJ, Wellington EMH. The biosynthesis of deoxynojirimycin and deoxymannonojirimycin in Streptomyces subrutilus. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1991;10:729–730. doi: 10.1039/C39910000729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huber DJ, Karakurt Y, Jeong J. Pectin degradation in ripening and wounded fruits. Revista Brasileira de Fisiologia Vegetal. 2001;13:224–241. doi: 10.1590/S0103-31312001000200009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme AC. The biochemistry of fruits and their products. London, New York: Academic Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Irfan M, Ghosh S, Meli VS, et al. Fruit ripening regulation of α-mannosidase expression by the MADS box transcription factor ripenig inhibitor and ethylene. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:10. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatoon R, MFB H, MM R. Ripening of tomato at different stages of maturity influenced by the post harvest application of ethrel. Bull Ins Trop Agric Kyushu Univ. 2013;36:017–030. [Google Scholar]

- Kiappes JL, Hill ML, Alonzi DS, et al. ToP-DNJ, a selective inhibitor of endoplasmic reticulum α-glucosidase II exhibiting antiflaviviral activity. ACS Chem Biol. 2018;13:60–65. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T, Nakagawa K, Saito Y, et al. Determination of 1-deoxynojirimycin in mulberry leaves using hydrophilic interaction chromatography with evaporative light scattering detection. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:1415–1418. doi: 10.1021/jf0306901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klee HJ, Giovannoni JJ. Genetics and control of tomato fruit ripening and quality attributes. Annu Rev Genet. 2011;45:41–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Narwal S, Kumar V, Prakash O. α-glucosidase inhibitors from plants: a natural approach to treat diabetes. Pharmacogn Rev. 2011;5:19. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.79096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Tao J, Zhang H. Peach gum polysaccharides-based edible coatings extend shelf life of cherry tomatoes. 3 Biotech. 2017;7:168. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0845-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S, Lee JG, Lee EJ. Comparison of fruit quality and GC–MS-based metabolite profiling of kiwifruit ‘Jecy green’: Natural and exogenous ethylene-induced ripening. Food Chem. 2017;234:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.04.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Zhao Y. Innovations in the development and application of edible coatings for fresh and minimally processed fruits and vegetables. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2007;6:60–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2007.00018.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln JE, Campbell AD, Oetiker J, et al. LE-ACS4, a fruit ripening and wound-induced 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase gene of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum). Expression in Escherichia coli, structural characterization, expression characteristics, and phylogenetic analysis. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:19422–19430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez GA, Chaves AR, Civello PM. β-xylosidase activity and expression of a β-xylosidase gene during strawberry fruit ripening. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2004;42:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire RG. Reporting of objective color measurements. HortScience. 1992;27:1254–1255. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI.27.12.1254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meli VS, Ghosh S, Prabha TN, et al. Enhancement of fruit shelf life by suppressing N-glycan processing enzymes. PNAS. 2010;107:2413–2418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909329107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GL. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal Chem. 1959;31:426–428. doi: 10.1021/ac60147a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myers RH, Montgomery DC. Response surface methodology: process and product optimization using designed experiments. New York: Wiley; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nawab A, Alam F, Hasnain A. Mango kernel starch as a novel edible coating for enhancing shelf-life of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruit. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;103:581–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norez C, Noel S, Wilke M, et al. Rescue of functional delF508-CFTR channels in cystic fibrosis epithelial cells by the α-glucosidase inhibitor miglustat. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2081–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna V, Prabha TN, Tharanathan RN. Fruit ripening phenomena—an overview. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2007;47:1–19. doi: 10.1080/10408390600976841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressey R, Avants JK. Occurrence and properties of polygalacturonase in avena and other plants. Plant Physiol. 1977;60:548–553. doi: 10.1104/pp.60.4.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priem B, Gitti R, Bush CA, Gross KC. Structure of ten free N-glycans in ripening tomato fruit (Arabinose is a constituent of a plant N-glycan) Plant Physiol. 1993;102:445–458. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.2.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladie M, Rose JKC, Watkins CB. Characterization of DFD (delayed fruit deterioration): a new tomato mutant. V Int Postharvest Symp. 2004;682:79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Shibano M, Fujimoto Y, Kushino K, et al. Biosynthesis of 1-deoxynojirimycin in Commelina communis: a difference between the microorganisms and plants. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:2661–2665. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skolik P, Morais CLM, Martin FL, McAinsh MR. Determination of developmental and ripening stages of whole tomato fruit using portable infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:236. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1852-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CJS, Watson CF, Bird CR, et al. Expression of a truncated tomato polygalacturonase gene inhibits expression of the endogenous gene in transgenic plants. Molec Gen Genet. 1990;224:477–481. doi: 10.1007/BF00262443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Nagata Y. Postharvest ethanol vapor treatment of tomato fruit stimulates gene expression of ethylene biosynthetic enzymes and ripening related transcription factors, although it suppresses ripening. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2019;152:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2019.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tateishi A, Mori H, Watari J, et al. Isolation, characterization, and cloning of α-l-arabinofuranosidase expressed during fruit ripening of Japanese Pear. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:1653–1664. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.056655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson D. Response surface experimentation1. J Food Process Preserv. 1982;6:155–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4549.1982.tb00650.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tieman DM, Harriman RW, Ramamohan G, Handa AK. An antisense pectin methylesterase gene alters pectin chemistry and soluble solids in tomato fruit. Plant Cell. 1992;4:667–679. doi: 10.2307/3869525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torchio F, Giacosa S, Vilanova M, et al. Use of response surface methodology for the assessment of changes in the volatile composition of Moscato bianco (Vitis vinifera L.) grape berries during ripening. Food Chem. 2016;212:576–584. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.05.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker GA, Grierson D. Synthesis of polygalacturonase during tomato fruit ripening. Planta. 1982;155:64–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00402933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma C, Kumar Mani A, Mishra S. Biochemical and molecular characterization of cell wall degrading enzyme, pectin methylesterase versus banana ripening: an overview. Asian J Biotechnol. 2016;9:1–23. doi: 10.3923/ajbkr.2017.1.23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H-M, Yin W-C, Wang C-K, To K-Y. Isolation of functional RNA from different tissues of tomato suitable for developmental profiling by microarray analysis. Bot stud. 2009;50:115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Yeats TH, Uluisik S, et al. Fruit Softening: Revisiting the role of pectin. Trends Plant Sci. 2018;23:302–310. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Baldwin E, Luo W, et al. Key tomato volatile compounds during postharvest ripening in response to chilling and pre-chilling heat treatments. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2019;154:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2019.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SF, Hoffman NE. Ethylene biosynthesis and its regulation in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1984;35:155–189. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.35.060184.001103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Huber DJ, Hurr BM, Rao J. Delay of tomato fruit ripening in response to 1-methylcyclopropene is influenced by internal ethylene levels. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2009;54:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2009.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Duan W, Chen K, Zhang B. Transcriptome and methylome analysis reveals effects of ripening on and off the vine on flavor quality of tomato fruit. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2020;162:111096. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2019.111096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.