Abstract

The caudal forelimb area (CFA) of the mouse cortex is essential in many forelimb movements, and diverse types of GABAergic interneuron in the CFA are distinct in the mediation of cortical inhibition in motor information processing. However, their long-range inputs remain unclear. In the present study, we combined the monosynaptic rabies virus system with Cre driver mouse lines to generate a whole-brain map of the inputs to three major inhibitory interneuron types in the CFA. We discovered that each type was innervated by the same upstream areas, but there were quantitative differences in the inputs from the cortex, thalamus, and pallidum. Comparing the locations of the interneurons in two sub-regions of the CFA, we discovered that their long-range inputs were remarkably different in distribution and proportion. This whole-brain mapping indicates the existence of parallel pathway organization in the forelimb subnetwork and provides insight into the inhibitory processes in forelimb movement to reveal the structural architecture underlying the functions of the CFA.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12264-019-00458-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Forelimb area, Input circuit, Interneuron, Parvalbumin, Somatostatin, Vasoactive intestinal peptide

Introduction

Complex movement patterns, such as forelimb motion, require the coordination of many muscles and joint movements that is specifically associated with neural activity in the cortical forelimb area (CFA) [1–3]. Cytoarchitectonic, electrophysiological, and behavioral experiments have shown that forelimb movements are regulated by several cortical areas, including the CFA [4, 5]. In mice, the CFA includes a portion of the primary motor cortex (CFAMOp) and somatosensory cortex (CFASSp), which are organized into two central nodes of the cortical forelimb subnetwork [6]. Each cortical area is significantly associated with different muscle groups and specific phases of forelimb motor tasks [3, 4, 7–9].

GABAergic neurons in the neocortex can be classified into three main groups: parvalbumin-positive (PV+), somatostatin-positive (SOM+), and vasoactive intestinal peptide-positive (VIP+). Physiological and functional studies have shown that different cortical interneuron types exhibit distinct and diverse activities in different behavioral states [10] and the long-range inputs to GABAergic interneurons are important in visual, auditory, and somatosensory cortical circuits [11–13]; however, the long-range inputs to different interneuron types in the CFA remain unclear. To illuminate their connective circuit mechanisms in mammalian forelimb subnetworks, it is imperative to map the synaptic inputs to CFA interneurons, including both local and long-range inputs, at the whole-brain level. Conventional neural tracing using retrograde chemical tracers has indicated that the CFA integrates long-range inputs from several sources including cortical areas and subcortical nuclei [6]; however, these methods have not demonstrated any input connections to specific types of neuron. Mouse lines with different kinds of Cre driver in conjunction with the monosynaptic rabies virus (RV) system [14, 15] provide a stable and reliable approach to map the long-range inputs to GABAergic neurons in the target region at the whole-brain level [16–20]. Therefore, we used monosynaptic RV in the CFAMOp and CFASSp of three GABAergic Cre lines to investigate the long-range inputs to different interneurons in the CFA.

Materials and Methods

Animals

VIP-Cre [B6J.Cg-Viptm1(cre)Zjh/AreckJ], PV-Cre [B6;129P2-Pvalbtm1(cre)Arbr/J], and SOM-Cre [B6N.Cg-Ssttm2.1(cre)Zjh/J] transgenic mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All mice were housed in an experimental animal barrier environment with a 12-h light/dark cycle and food and water ad libitum. Only adult mice (2–3 months old) were used. All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Surgery and Stereotaxic Viral Injection

The mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 10% ethylurethane, 2% chloral hydrate, and 1.7 mg/mL xylazine mixed in 0.9% NaCl (0.1 mL/10 g body weight). Then the anesthetized mice were mounted on a stereotaxic holder (item 68030, RWD Life Science, Shenzhen, China), and the angle of the skull was adjusted before craniotomy. We set the bregma and lambda points at the same level and the left and right hemispheres were symmetrical with the center line on the plane. A small hole (~0.5 mm diameter) was bored through the skull above the target region using a dental drill. All the viral tools were injected through a glass micropipette connected to a pressure injection pump (Nanoject II: Drummond Scientific Co., Broomall, PA) at 35 nL/min. After the operation, the wound was treated with lincomycin hydrochloride to prevent inflammation.

The monosynaptic RV system was as described previously [14, 21], and all the viral tools used were provided by BrainVTA Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). We first injected 150 nL adeno-associated helper viruses (AAV helper) into the CFAMOp upper limb region [antero-posterior (AP), 1.34 mm from bregma; medio-lateral (ML), 1.75 mm; dorso-ventral (DV), −1.5 mm], or the CFASSp upper limb region (AP, 0.14 mm; ML, 2.2 mm; DV, −1.4 mm) in PV-Cre, SOM-Cre, and VIP-Cre mice. The AAV helper was mixed with rAAV2/9-Ef1α-DIO-BFP-2a-TVA-WPRE-pA and rAAV2/9-Ef1α-DIO-RG-WPRE-pA at a ratio of 1:2, and the final titer was 2.30 × 1012 viral genomes/mL. Three weeks later, we repeated the operation and injected 300 nL RV-ΔG-EnvA-EGFP in the same area at a titer of 2.00 × 108 infectious units/mL.

Histology

Approximately one week after RV injection, mice were anesthetized and perfused with 0.01 mol/L phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA; Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.01 mol/L PBS. The perfused brains were immersed in 4% PFA for 24 h and then placed in 0.01 mol/L PBS for 4 h at 4 °C before embedding. The procedures of agarose embedding were based on previous research [22]. Briefly, agarose type I (Sigma-Aldrich) was oxidized by stirring in 10 mmol/L sodium periodate (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3 h at room temperature and the oxidized product was then washed repeatedly in PBS at a final concentration of 5%. The brains were embedded in melted oxidized agarose using a silicone mold and maintained at 4 °C for solidification. The embedded brains were sectioned at 50 µm on a vibrating microtome (Leica VT1200S; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

For immunohistochemistry, selected sections were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) containing 0.3% Triton in 0.01 mol/L PBS. One hour later, the following primary antibodies were added and incubated for ~12 h at 4 °C: anti-PV (1:1,000, mouse, Millipore, MAB1572; Burlington, MA), anti-SOM (1:200, goat, Santa Cruz, sc-7819; Dallas, TX), and anti-ChAT (1:500, goat, Millipore, AB144P). After rinsing five times in PBS, these sections were incubated with the following fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature: donkey anti-goat (Alexa Fluor 647, 1:500, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) and goat anti-mouse (Alexa Fluor 647, 1:500, Invitrogen). All the antibodies were diluted in 5% BSA. DAPI at 5 µg/mL was used to stain nuclei.

Microscopy and Analysis

For whole-brain input counting, 50-µm sections were mounted with 50% glycerol and visualized using a slide-scanning microscope (× 4, 0.2 NA objective; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). For imaging starter cells and immunohistochemistry, selected sections were mounted with 50% glycerol and then imaged on an inverted confocal microscope (× 10, 0.45 NA objective, Zeiss LSM 710; × 20, 0.75 NA objective Zeiss LSM 710; Oberkochen, Germany).

The RV-GFP-labeled input neurons were manually counted using the Fiji (NIH, Bethesda, MD) Cell Counter plug-in, and their locations were defined according to the Allen brain atlas [23]. All the abbreviations for brain region used here are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The proportion of input from each brain area was normalized to the total number of long-range inputs.

Statistics

All the graphs were generated in GraphPad Prism v.8.02 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) and statistical results are presented as the mean ± SEM. The individual data points are shown in histograms and though the data distributions were assumed to be normal, this was not formally tested. The two-tailed Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc tests were performed using SPSS (version 23; IBM, Armonk, NY). To quantify the similarity in input patterns, we calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficients and the significance level was set to P < 0.05.

Results

Tracing Monosynaptic Inputs to Different Interneuron Types in the CFA

To label the whole-brain input connection patterns of three interneuron types in the CFA, we used three Cre lines that expressed Cre recombinase in PV+, SOM+, and VIP+ neurons. We delivered AAV as a helper virus carrying specific DNA sequences that coded TVA, BFP, and G proteins (AAV-DIO-BFP-TVA and AAV-DIO-RG) into mouse brains (Fig. 1A,B). The injection sites of all samples were concentrated in the CFA (Fig. 1C). The interneurons that demonstrated Cre recombinase expressed BFP, the avian receptor TVA, and rabies glycoprotein (RG). Three weeks later, we delivered RV-EnvA-GFP into the same region (Fig. 1A,B). Only neurons that expressed TVA and RG simultaneously were infected by RV and spread the virus retrogradely to presynaptic cells. One week after RV injection, we imaged the brains. In each group, the distribution of the majority of starter cells was restricted to the CFA (Fig. 1D). Local input cells in the CFA were labeled with EGFP, while the neurons that co-expressed BFP and EGFP were defined as starter cells (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Strategies for tracing monosynaptic inputs to three interneuron types in the CFA. A Recombinant AAV helper viruses and genetically-modified RV. B Experimental design. C Diagram showing the central coordinates of every injection site in the CFA. Each colored spot indicates one animal, and different colors indicate different Cre lines. D Coronal sections showing the injection site and the distribution of starter cells in each group (scale bars, 100 μm). E Starter cells of the three interneuron types (arrowheads, scale bars, 50 μm). F Individual layer-specific distribution of starter cells in the three interneuron types. Each line indicates one coronal section (upper x-axis, distance from pia; lower x-axis, layer distribution of each starter cell; each colored spot indicates a single starter cell; blue, PV+; red, SOM+; orange, VIP+ starter cells).

To dissect the layer-specific distribution of starter cells across the three major interneuron types, we measured the distance between each starter cell and the pial surface (Fig. 1F). PV+ starter cells were found throughout the cortical layers with most located in superficial layers; SOM+ starter cells were primarily distributed in layer V, consistent with the known distribution of SOM+ interneurons in the neocortex [24]; and VIP+ starter cells in the CFA were primarily detected in the superficial layers.

Whole-brain Mapping of Long-range Inputs to Three Interneuron Types in the CFA

Whole-brain mapping of the monosynaptic input neurons was accomplished in 62 discrete nuclei in the three kinds of mice. Representative coronal sections showed that all three interneuron types in the CFA received major long-range inputs from ipsilateral cortical, thalamic, and cerebral nuclei and contralateral cortex that had already been identified (Fig. 2A). We quantified the GFP-labeled neurons in coronal sections of labeled mice. According to the standard mouse brain atlas [23], there were 48,249 PV-Cre (3 mice), 24,706 SOM-Cre (4 mice), and 11,925 VIP-Cre (3 mice) long-range input neurons. Although the CFAMOp contained a large number of GFP-labeled neurons, we could not confirm that these were directly rabies-infected interneurons (TVA+ only) at the injection site.

Fig. 2.

Overview of whole-brain input connections to three interneuron types in the CFA. A Representative coronal sections showing the main long-range inputs to PV+, SST+, and VIP+ interneurons in the CFA (yellow, cortical regions; orange, subcortical regions; scale bar, 2 mm). B–E Proportions of input from the ipsilateral hemisphere (B), contralateral hemisphere (C), deep and superficial ipsilateral motor-sensory cortex (D), and ipsilateral cortex except motor-sensory cortex (E) to each interneuron type (mean ± SEM).

The ipsilateral cortex was the most important source of long-range input to the three types of interneuron in the CFAMOp, accounting for ~75% of the total long-range inputs (VIP-Cre, 74.5% ± 6.4%; PV-Cre, 74.4% ± 4.2%; SOM-Cre, 75.0% ± 4.1%; Fig. 2B). The majority of the ipsilateral input was derived from the motor-sensory cortex and the thalamus, while fewer input neurons were located in the frontal pole cortex, orbital cortex, cerebral nuclei, hypothalamus, midbrain, pons, and other cortical regions (Fig. 2B). The input neurons in the contralateral hemisphere were mainly distributed in the motor-sensory and orbital cortex; however, almost no RV-GFP-labeled neurons were found in the subcortical area (Fig. 2A, C).

Cortical Input to Three Interneuron Types in the CFA

The cortical PV+, SOM+, and VIP+ interneurons were preferentially located in different cortical layers (Fig. 1E), and previous studies established that cortico-cortical projections have layer-specific patterns [25]. To further analyze the layer-specific patterns of cortical inputs to the CFA, we separated the main motor-sensory cortical inputs into superficial (layers II and III) and deep (V and VI) populations. Deep and superficial cortical inputs were detected in multiple regions, such as the secondary motor cortex, the nose and mouth areas of primary sensory cortex, the upper and lower limb areas of primary sensory cortex, the secondary somatosensory area (SSs), and the barrel cortex (Fig. 2D). A few input neurons were found in layer IV, particularly in the nose and mouth areas of primary sensory cortex and SSs, and we clustered them into the superficial input group. Our quantitative analysis showed no significant difference between the proportion of deep and superficial cortical inputs to each interneuron type (Fig. 2D). Intra-telencephalic neurons, which projected to the cerebral cortex and striatum, were distributed in layers II/III and V/VI [26]. This result indicates that all three types of CFA interneurons received uniform input from deep and superficial intra-telencephalic neurons.

We also found that SOM+ neurons were most closely associated with the limb-related sensory cortex and received more direct input connections than PV+ (P = 0.023) and VIP+ (P = 0.018) neurons (Fig. 2D). Moreover, compared to VIP+ neurons, SOM+ and PV+ neurons received more inputs from the orbital cortex and agranular insular area, which are associated with somatosensory and emotional control. Sparse or negligible long-range input neurons were detected within the isocortex, olfactory areas, hippocampal formation, and cortical subplate (Fig. 2E).

Subcortical Input to Three Interneuron Types in the CFA

Subcortical mapping of the RV-GFP-labeled neurons showed that the thalamus and cerebral nuclei were prominent long-range subcortical input sources for CFA interneurons (Fig. 2B), consistent with previous structural studies of CFA pyramidal neurons [25]. In our data, the striatal input was weak or negligible, while major direct input neurons were observed in the pallidum, especially in the external segment of the globus pallidus (GPe). We found that SOM+ neurons received more input from the GPe than PV+ neurons (P = 0.033) (Fig. 3A). A similar pattern of GPe input distribution was evident in the different Cre lines, in that RV-GFP-labeled neurons were concentrated in the rostrolateral and caudoventral regions (Fig. 3B). As the pallidum is the main source of the corticopetal cholinergic projection [26, 27], we assessed the proportions of neurons co-labeled with choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) antibodies and RV-GFP in PV-Cre (2 mice, 26 cells) and SOM-Cre (2 mice, 7 cells) mice. The results demonstrated proportions >80% in both groups (Fig. 3C, D), suggesting that the majority of GPe inputs to the CFA SOM+ and PV+ interneurons are corticopetal cholinergic neurons.

Fig. 3.

Subcortical input connections to three interneuron types in the CFA. A Proportions of cerebral nuclear input to each interneuron type (mean ± SEM). B Coronal sections showing the distribution of GPe input to each interneuron type (scale bar, 500 μm). C Identification of RV-GFP+/ChAT+ input neurons in the GPe (scale bar, 50 μm). D Proportions of RV-GFP-labeled neurons expressing ChAT in the GPe (mean ± SEM). E Proportions of input from the thalamus (mean ± SEM). F Proportions of input from other brainstem regions except the thalamus (mean ± SEM).

The thalamic input accounted for ~10% of the whole-brain input to CFA interneurons (VIP-Cre, 13.8% ± 3.1%; PV-Cre, 9.7% ± 0.9%; SOM-Cre, 12.6% ± 1.8%). Whole-thalamus analysis revealed that CFA interneurons received equal proportions of thalamic input from the sensory-motor cortex-related thalamus and polymodal association cortex-related thalamus (Fig. 3E). In the latter, each interneuron type received similar proportions of input from all major thalamic input structures, such as the posterior medial nucleus (PO), mediodorsal nucleus, nucleus reuniens, central medial nucleus, paracentral nucleus, and parafascicular nucleus (PF). In the sensory-motor cortex-related thalamus, the major inputs came from the ventral anterior-lateral nucleus (VAL) and the ventral medial nucleus (VM) of the thalamus. Each CFA interneuron type received similar input from the VM, while VIP+ neurons received more inputs from the VAL than the PV+ neurons (P = 0.048) (Fig. 3E). This result suggested that higher-order thalamic nuclei forward information equally to each interneuron type in the CFA, while VAL activation might promote the disinhibition of neuronal activity in forelimb movement via VIP+ interneurons.

Moreover, we detected a few RV-GFP-labeled neurons in the lateral hypothalamic area, lateral preoptic area, and zona incerta of the hypothalamus; periaqueductal gray, ventral tegmental area, dorsal raphe nucleus, substantia nigra pars compacta, and pedunculopontine nucleus of the midbrain; and the pontine reticular nucleus, superior central raphe nucleus, parabrachial nucleus, laterodorsal tegmental nucleus, and locus ceruleus of the pons (Fig. 3F). These nuclei might be part of the source of cortically-modulated signals.

Distinct Whole-brain Long-range Input to CFAMOp and CFASSp Interneurons

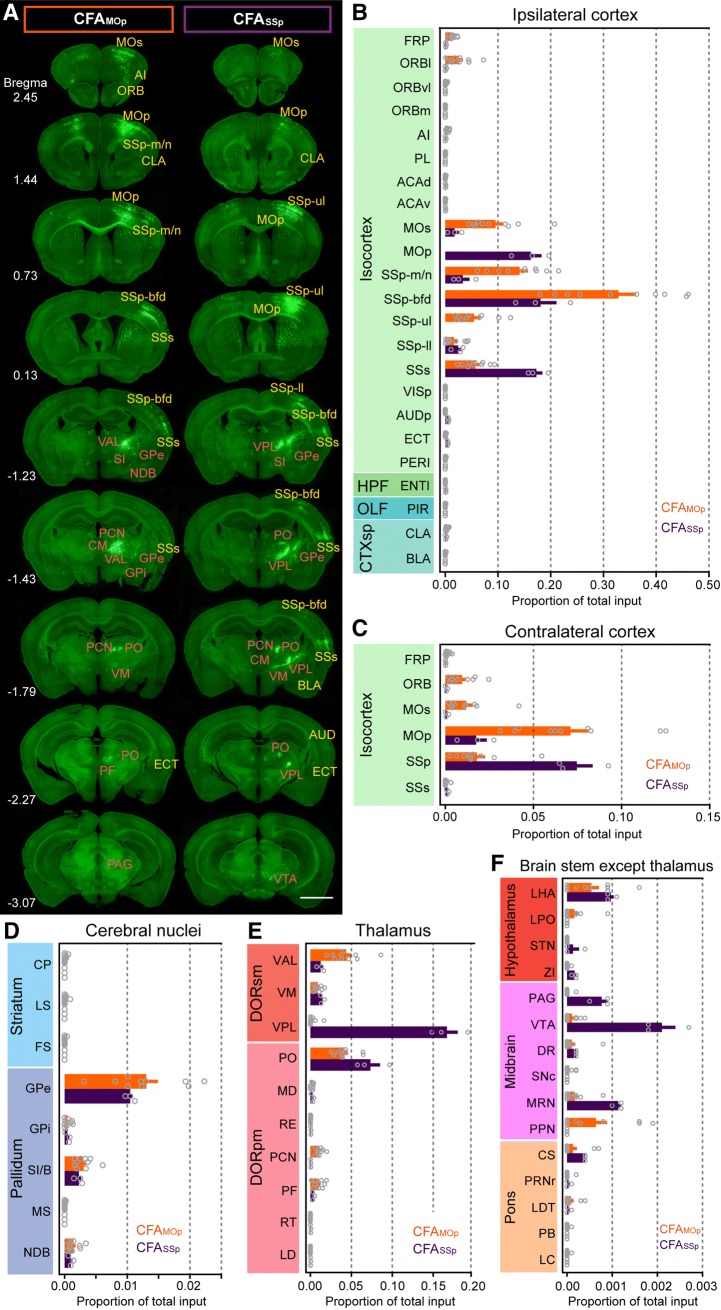

We divided the CFA into two sub-regions to explore the structural connections between forelimb motor and forelimb sensory activity. We labeled whole-brain monosynaptic input to the interneurons in CFASSp, which were mainly located in SSp-ul, another somatic sensorimotor node in the upper limb subnetwork [6]. Compared with CFAMOp, we found that interneurons in CFASSp also received major inputs from the cerebral cortex, cerebral nuclei, and thalamus. Most of CFASSp input sources also had projections to the CFAMOp (Fig. 4A); however, quantitative analysis indicated that the proportions of input to CFAMOp and CFASSp were remarkably different in different brain areas (Fig. 4B–F).

Fig. 4.

Overview of whole-brain input connections to interneurons in the CFAMOp/CFASSp. A Representative coronal sections showing the contrast of input connections to VIP+ interneurons in the CFAMOp and CFASSp (yellow, cortical regions; orange, subcortical regions; scale bar, 2 mm). B Quantitative analysis of the proportions of long-range inputs from the ipsilateral cortex to the CFAMOp and CFASSp (mean ± SEM). C Proportions of input from the contralateral hemisphere (mean ± SEM). D Proportions of input from cerebral nuclei (mean ± SEM). E Proportions of input from the thalamus (mean ± SEM). F Proportions of input from other brainstem regions except the thalamus (mean ± SEM).

Notably, in the cerebral cortex the motor-sensory cortex had the strongest connectivity with both CFAMOp and CFASSp; however, nose and mouth areas of primary sensory cortex and barrel cortex preferentially projected to the interneurons in the CFAMOp rather than in the CFASSp, consistent with the actual movement patterns of the mice (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, neurons in anterior cortical regions, such as the frontal association cortex, orbital cortex, agranular insular area, and secondary motor cortex provided more direct projections to the interneurons in the CFAMOp; however, neurons in caudal cortical regions, such as SSs, primary auditory cortex, and the ectorhinal area, had more direct projections to the CFASSp, which followed the topological structure of the two CFA sub-regions (Fig. 4B). We did not observe CFASSp interneurons receiving input from the frontal pole and orbital cortex of the contralateral cortex (Fig. 4A, C).

In the cerebral nuclei, we did not observe any striatal input neurons in CFASSp RV-labeled samples (n = 3); in the pallidum, we detected similar proportions of input to the CFAMOp and CFASSp (Fig. 3D). In the thalamus, the CFAMOp interneurons received input primarily from the VAL (P = 0.002), paracentral nucleus (P = 0.002), and PF (P = 0.011), while the CFASSp interneurons preferentially received input from the VPL (P = 0.006) and PO (P = 0.008) (Fig. 4E). In other brainstem regions, the proportion of input to the CFA was <0.2%. The midbrain, especially the ventral tegmental area, is known to contain a high density of dopaminergic neurons and provided more direct projections to the interneurons in the CFASSp (P = 0.022), while few RV-GFP-labeled neurons were detected in the substantia nigra pars compacta (Fig. 4A, F). This result suggests that the dopamine signal in the forelimb subnetwork might primarily arise from the ventral tegmental pathway and innervate CFASSp interneurons.

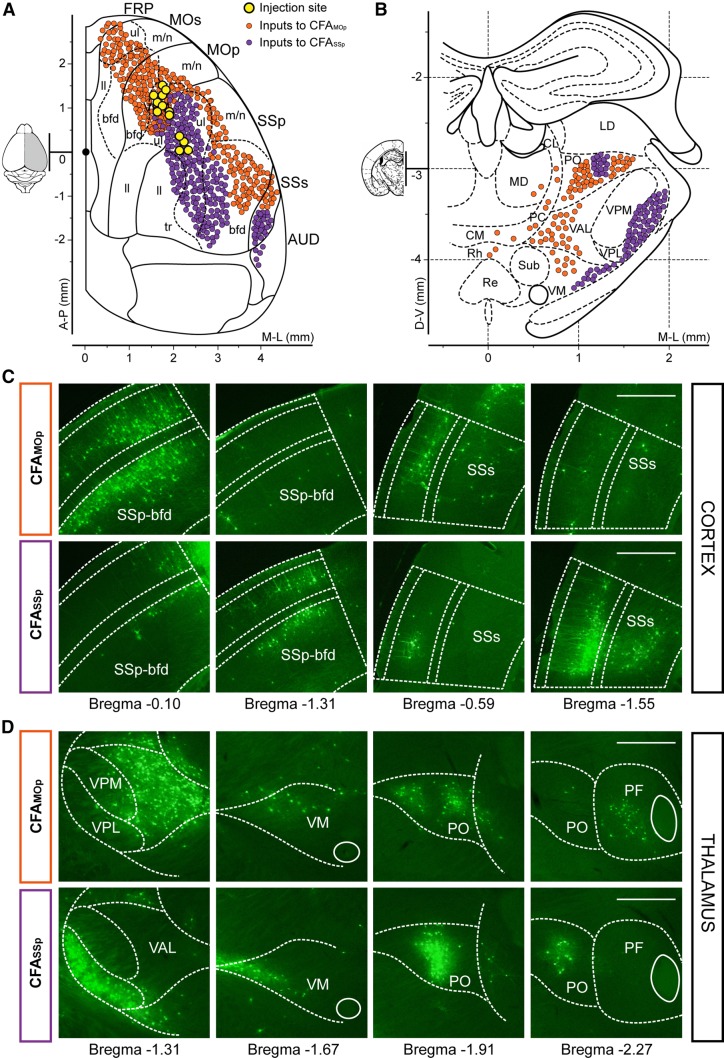

Parallel Pathways of Cortical and Thalamic Inputs to the CFAMOp and CFASSp

Quantitative analysis showed that both CFAMOp and CFASSp interneurons received a large number of direct inputs from barrel cortex and the SSs; however, the input neurons that projected to the CFAMOp were mainly distributed in the anterolateral barrel cortex, while those that directly projected to the CFASSp were mainly distributed posterolaterally. Following a similar topological organization, in the SSs the inputs to the CFAMOp were mainly distributed in the anterior area, while the inputs to the CFASSp were mainly distributed caudally (Fig. 5A, C). These results suggest that the interneurons in CFAMOp and CFASSp receive distinct sensory information from two parallel cortical pathways.

Fig. 5.

Cortical and thalamic input connection patterns of CFA interneurons. A, B Schematic diagrams of the cortical (A) and thalamic (B) inputs to CFAMOp or CFASSp interneurons (yellow, injection sites of AAV and RV; orange, inputs to CFAMOp interneurons; purple, inputs to CFASSp interneurons). C Coronal sections showing the different cortical input connection patterns. Input neurons distributed in anterior (barrel field, bregma −0.10 mm; SSs, −0.59 mm) and caudal regions (barrel field, −1.31 mm; SSs, −1.55 mm) (sections from two VIP-Cre mice; scale bars, 500 μm). D Coronal sections showing the different thalamic input connection patterns. Input neurons distributed in VAL/VPL (bregma −1.31 mm), VM (−1.67 mm), PO (−1.91 mm), and PF (−2.27 mm) (sections from two VIP-Cre mice; scale bars, 500 μm).

We showed that both CFAMOp and CFASSp interneurons received major thalamic inputs from the higher-order PO thalamic nuclei (Fig. 3E, 4E). Worthy of mention is that the PO neurons that projected to the CFAMOp were mainly distributed laterally, while the neurons that projected to the CFASSp were only distributed in the central region (Fig. 5B, D). Interestingly, the separation of thalamus–CFA sub-loops was not only observed in the PO, but also in the VM and PF (Fig. 5D). Consistent with parallel cortical pathways, this result in the thalamus also suggests the existence of parallel pathways in the forelimb subnetwork, which are only related to one another (i.e., not identical). Furthermore, the separation of lateral and central parts in the PO is helpful in understanding the complex higher-order thalamic nuclei.

Discussion

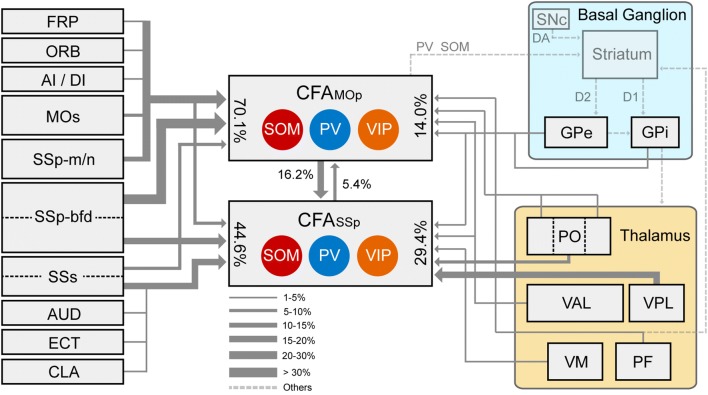

Using the monosynaptic RV system, we studied the long-range input connections of CFA interneurons at the whole-brain level in mice, and generated a comprehensive long-range input atlas of interneurons in the CFAMOp and CFASSp. All of the PV+, SOM+, and VIP+ interneurons in the CFA received major long-range inputs from the cerebral cortex, pallidum, and thalamus to varying degrees (Fig. 6). Notably, the interneurons in different sub-regions of the CFA received long-range inputs from the cortex and thalamus in remarkably differing distributions and proportions. These differences were not only reflected in the known structures, but also in brain areas that had not yet been subdivided. The anatomical evidence indicated that the interneurons in the CFAMOp and CFASSp have distinct connectivity subnetworks, and the connectivity mapping provides important guidance for further understanding the inhibitory regulatory processes in forelimb movement and the structural architecture underlying the functions of the CFA.

Fig. 6.

Schematic of the main long-range input connection patterns to the GABAergic interneurons in the CFA: the cortico-cortical projections (left); the interactions between CFAMOp and CFASSp (middle); and the inputs from the thalamus and the basal ganglia (right). Percentages represent the proportion of total long-range inputs at the whole-brain level. Line thickness represents the range of proportions.

Diverse GABAergic interneuron types in the neocortex have a characteristically low density and are highly heterogeneous. These interneurons only account for ~20% of cortical neurons, but they are divided into a number of different subtypes according to their morphological, physiological, and biochemical characteristics [25, 28–30]. Although there is still no clear consensus on how many inhibitory cell types there are, PV+, SOM+, and VIP+ are generally considered to be the three major non-overlapping classes of interneuron in the mouse neocortex [29]. Using the monosynaptic RV tracing system, VIP+ interneurons in the barrel cortex received a significantly greater proportion of distant cortical input from deep layers than the PV+ or SOM+ neurons [15]; however, this may not be a common characteristic among all cortical interneurons because we found that the three interneuron types in the CFAMOp received deep cortical inputs in similar proportions (VIP-Cre, 37.5% ± 4.4%; PV-Cre, 35.7% ± 1.6%; SOM-Cre, 37.6% ± 2.2%). We consider that this difference may be due to the distribution of starter cells, but this has not yet been confirmed.

Both the PV+ and SOM+ interneurons in the CFAMOp received direct projections from the GPe, which mainly co-releases GABA and acetylcholine to inhibit and activate interneurons and pyramidal neurons across cortical layers [27]. The cortico-striatal PV+/SOM+ projecting neurons directly innervate striatal dopamine (D1/D2) receptor neurons, while striatal information flows to the internal segment of the globus pallidus and GPe through D1/D2 receptor neurons from direct and indirect pathways [31, 32]. This suggests that PV+ and SOM+ interneurons in the CFAMOp contribute to the MOp–STR–GPe–MOp inhibitory microcircuit and the neural activity may be modulated by striatal GABAergic spiny projection neurons that bypass the thalamus. Furthermore, CFAMOp interneurons receive direct input from the PF, which projects to both the somatosensory cortex and the dorsolateral striatum [33]; however, our results showed that the PF preferentially innervates the motor rather than the sensory cortex.

Moreover, in the thalamus, PO is the major source of long-range subcortical information to CFAMOp interneurons, and the proportions among the three groups displayed no significant differences. In the somatosensory cortex, the terminals of thalamo-cortical PO neurons were densely assembled in layers I and Va and preferentially innervated PV+ interneurons in layer Va and VIP+ interneurons in layer II [34, 35]. Our structural results in the CFA confirmed that the monosynaptic inputs to SOM+ interneurons were densely distributed in the PO, consistent with both PV+ and VIP+ interneurons in the CFA. The innervation of such structural connections is unclear, but we also provided thalamo-cortical connections that provide a basis for functional research on SOM+ interneurons.

We also compared the distributions and proportions of long-range inputs to interneurons in different CFA sub-regions, and found that the cortex and thalamus were the most important long-range input sources that connect to the CFA; however, GABAergic interneurons in the CFAMOp received more cortico-cortical projections, while the CFASSp interneurons received more thalamic inputs (Fig. 6). The proportion of cortical inputs to CFASSp VIP+ neurons was 70.4% ± 1.7%, whereas the proportion of CFAMOp VIP+ neurons was 84.1% ± 3.1%. In contrast, the proportion of input from the thalamus to the CFASSp was 27.4% ± 1.7%, and to the CFAMOp was only 13.8% ± 3.1%. We speculated that the neurons located in the anterior cortex preferentially receive more cortico-cortical inputs and fewer thalamo-cortical inputs than those in the posterior cortex.

The barrel cortex is generally considered to be structurally and functionally equivalent to the somatosensory cortex [12, 15, 35]; in our study, direct input signals from multiple sub-regions of the somatosensory cortex to CFA interneurons were counted separately, and the inputs from barrel cortex and SSs were anatomically organized into two cortical information channels to CFA interneurons. In the thalamus, the higher-order PO thalamic nucleus is subdivided into four subnuclei according to their connection with layer Vb neurons in the barrel cortex [36]; however, we first separated the PO into lateral and central portions in the forelimb-movement subnetwork. The segregation of two CFA–PO loops may also support the concept of parallel pathway organization in the forelimb-movement system.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Qingtao Sun, Pan Luo, Mei Yao, and Peilin Zhao for help with experiments and data analysis. We thank the Optical Bioimaging Core Facility of Huazhong University of Science and Technology for providing support with data acquisition. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61721092, 91749209, and 31871088) and the Director Fund of Wuhan National Laboratory for Optoelectronics.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Iwaniuk AN, Whishaw IQ. On the origin of skilled forelimb movements. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:372–376. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01618-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemon RN. Descending pathways in motor control. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:195–218. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang X, Liu Y, Li X, Zhang Z, Yang H, Zhang Y, et al. Deconstruction of corticospinal circuits for goal-directed motor skills. Cell. 2017;171(440–455):e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tennant KA, Adkins DL, Donlan NA, Asay AL, Thomas N, Kleim JA, et al. The organization of the forelimb representation of the C57BL/6 mouse motor cortex as defined by intracortical microstimulation and cytoarchitecture. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:865–876. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Touvykine B, Mansoori BK, Jean-Charles L, Deffeyes J, Quessy S, Dancause N. The effect of lesion size on the organization of the ipsilesional and contralesional motor cortex. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2016;30:280–292. doi: 10.1177/1545968315585356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zingg B, Hintiryan H, Gou L, Song MY, Bay M, Bienkowski MS, et al. Neural networks of the mouse neocortex. Cell. 2014;156:1096–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramanathan D, Conner JM, Tuszynski MH. A form of motor cortical plasticity that correlates with recovery of function after brain injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11370–11375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601065103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison TC, Ayling OG, Murphy TH. Distinct cortical circuit mechanisms for complex forelimb movement and motor map topography. Neuron. 2012;74:397–409. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hira R, Terada S, Kondo M, Matsuzaki M. Distinct functional modules for discrete and rhythmic forelimb movements in the mouse motor cortex. J Neurosci. 2015;35:13311–13322. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2731-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sachidhanandam S, Sermet BS, Petersen CCH. Parvalbumin-expressing GABAergic neurons in mouse barrel cortex contribute to gating a goal-directed sensorimotor transformation. Cell Rep. 2016;15:700–706. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson A, Schneider DM, Takatoh J, Sakurai K, Wang F, Mooney R. A circuit for motor cortical modulation of auditory cortical activity. J Neurosci. 2013;33:14342–14353. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2275-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S, Kruglikov I, Huang ZJ, Fishell G, Rudy B. A disinhibitory circuit mediates motor integration in the somatosensory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1662–1670. doi: 10.1038/nn.3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang S, Xu M, Kamigaki T, Hoang Do JP, Chang WC, Jenvay S, et al. Selective attention. Long-range and local circuits for top-down modulation of visual cortex processing. Science. 2014;345:660–665. doi: 10.1126/science.1254126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wickersham IR, Lyon DC, Barnard RJ, Mori T, Finke S, Conzelmann KK, et al. Monosynaptic restriction of transsynaptic tracing from single, genetically targeted neurons. Neuron. 2007;53:639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Yang H, Pan L, Hao S, Wu X, Zhan L, et al. Brain-wide mapping of mono-synaptic afferents to different cell types in the laterodorsal tegmentum. Neurosci Bull. 2019;35:781–790. doi: 10.1007/s12264-019-00397-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wall NR, De La Parra M, Sorokin JM, Taniguchi H, Huang ZJ, Callaway EM. Brain-wide maps of synaptic input to cortical interneurons. J Neurosci. 2016;36:4000–4009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3967-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang S, Xu M, Chang WC, Ma C, Hoang Do JP, Jeong D, et al. Organization of long-range inputs and outputs of frontal cortex for top-down control. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1733–1742. doi: 10.1038/nn.4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su YT, Gu MY, Chu X, Feng X, Yu YQ. Whole-brain mapping of direct inputs to and axonal projections from GABAergic neurons in the parafacial zone. Neurosci Bull. 2018;34:485–496. doi: 10.1007/s12264-018-0216-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Z, Chen Z, Fan G, Li A, Yuan J, Xu T. Cell-type-specific afferent innervation of the nucleus accumbens core and shell. Front Neuroanat. 2018;12:84. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2018.00084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo P, Li A, Zheng Y, Han Y, Tian J, Xu Z, et al. Whole brain mapping of long-range direct input to glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons in motor cortex. Front Neuroanat. 2019;13:44. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2019.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun Q, Li X, Ren M, Zhao M, Zhong Q, Ren Y, et al. A whole-brain map of long-range inputs to GABAergic interneurons in the mouse medial prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:1357–1370. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0429-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang T, Long B, Gong H, Xu T, Li X, Duan Z, et al. A platform for efficient identification of molecular phenotypes of brain-wide neural circuits. Sci Rep. 2017;7:13891. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14360-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oh SW, Harris JA, Ng L, Winslow B, Cain N, Mihalas S, et al. A mesoscale connectome of the mouse brain. Nature. 2014;508:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature13186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu X, Roby KD, Callaway EM. Immunochemical characterization of inhibitory mouse cortical neurons: three chemically distinct classes of inhibitory cells. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:389–404. doi: 10.1002/cne.22229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hooks BM, Mao T, Gutnisky DA, Yamawaki N, Svoboda K, Shepherd GM. Organization of cortical and thalamic input to pyramidal neurons in mouse motor cortex. J Neurosci. 2013;33:748–760. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4338-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Yu B, Sun Q, Zhang Y, Ren M, Zhang X, et al. Generation of a whole-brain atlas for the cholinergic system and mesoscopic projectome analysis of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:415–420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1703601115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saunders A, Oldenburg IA, Berezovskii VK, Johnson CA, Kingery ND, Elliott HL, et al. A direct GABAergic output from the basal ganglia to frontal cortex. Nature. 2015;521:85–89. doi: 10.1038/nature14179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feldmeyer D, Qi G, Emmenegger V, Staiger JF. Inhibitory interneurons and their circuit motifs in the many layers of the barrel cortex. Neuroscience. 2018;368:132–151. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tremblay R, Lee S, Rudy B. GABAergic interneurons in the neocortex: from cellular properties to circuits. Neuron. 2016;91:260–292. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee S, Hjerling-Leffler J, Zagha E, Fishell G, Rudy B. The largest group of superficial neocortical GABAergic interneurons expresses ionotropic serotonin receptors. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16796–16808. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1869-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmitz Y, Luccarelli J, Kim M, Wang M, Sulzer D. Glutamate controls growth rate and branching of dopaminergic axons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:11973–11981. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2927-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melzer S, Gil M, Koser DE, Michael M, Huang KW, Monyer H. Distinct corticostriatal GABAergic neurons modulate striatal output neurons and motor activity. Cell Rep. 2017;19:1045–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mandelbaum G, Taranda J, Haynes TM, Hochbaum DR, Huang KW, Hyun M, et al. Distinct cortical-thalamic-striatal circuits through the parafascicular nucleus. Neuron. 2019;102(636–652):e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aronoff R, Matyas F, Mateo C, Ciron C, Schneider B, Petersen CC. Long-range connectivity of mouse primary somatosensory barrel cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:2221–2233. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Audette NJ, Urban-Ciecko J, Matsushita M, Barth AL. POm thalamocortical input drives layer-specific microcircuits in somatosensory cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2018;28:1312–1328. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sumser A, Mease RA, Sakmann B, Groh A. Organization and somatotopy of corticothalamic projections from L5B in mouse barrel cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:8853–8858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704302114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.