Listeria monocytogenes is the causative agent of listeriosis, an infectious and fatal disease of animals and humans. In this study, we have shown that lysR contributes to Listeria pathogenesis and replication in cell lines. We also highlight the importance of lysR in regulating the transcription of genes involved in different pathways that might be essential for the growth and persistence of L. monocytogenes in the host or under nutrient limitation. Better understanding L. monocytogenes pathogenesis and the role of various virulence factors is necessary for further development of prevention and control strategies.

KEYWORDS: Listeria, virulence, RNA sequence, Listeria monocytogenes, transcription regulator

ABSTRACT

The capacity of Listeria monocytogenes to adapt to environmental changes is facilitated by a large number of regulatory proteins encoded by its genome. Among these proteins are the uncharacterized LysR-type transcriptional regulators (LTTRs). LTTRs can work as positive and/or negative transcription regulators at both local and global genetic levels. Previously, our group determined by comparative genome analysis that one member of the LTTRs (NCBI accession no. WP_003734782) was present in pathogenic strains but absent from nonpathogenic strains. The goal of the present study was to assess the importance of this transcription factor in the virulence of L. monocytogenes strain F2365 and to identify its regulons. An L. monocytogenes strain lacking lysR (the F2365ΔlysR strain) displayed significant reductions in cell invasion of and adhesion to Caco-2 cells. In plaque assays, the deletion of lysR resulted in a 42.86% decrease in plaque number and a 13.48% decrease in average plaque size. Furthermore, the deletion of lysR also attenuated the virulence of L. monocytogenes in mice following oral and intraperitoneal inoculation. The analysis of transcriptomics revealed that the transcript levels of 139 genes were upregulated, while 113 genes were downregulated in the F2365ΔlysR strain compared to levels in the wild-type bacteria. lysR-repressed genes included ABC transporters, important for starch and sucrose metabolism as well as glycerolipid metabolism, flagellar assembly, quorum sensing, and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis. Conversely, lysR activated the expression of genes related to fructose and mannose metabolism, cationic antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) resistance, and beta-lactam resistance. These data suggested that lysR contributed to L. monocytogenes virulence by broad impact on multiple pathways of gene expression.

IMPORTANCE Listeria monocytogenes is the causative agent of listeriosis, an infectious and fatal disease of animals and humans. In this study, we have shown that lysR contributes to Listeria pathogenesis and replication in cell lines. We also highlight the importance of lysR in regulating the transcription of genes involved in different pathways that might be essential for the growth and persistence of L. monocytogenes in the host or under nutrient limitation. Better understanding L. monocytogenes pathogenesis and the role of various virulence factors is necessary for further development of prevention and control strategies.

INTRODUCTION

The Gram-positive, intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenes is one of the most costly foodborne pathogens due to the costs of health care and significant food recalls (1). Listeria is responsible for 28% of annual deaths attributable to known foodborne pathogens (2). This bacterium has an extremely adaptable metabolism that enables survival under a variety of environmental conditions, including extracellular, abiotic, and intracellular environments. A successful transition of L. monocytogenes in response to these environmental changes requires a precise regulatory system that adjusts the metabolism (3, 4).

The transcription regulation of many L. monocytogenes virulence genes is controlled partially by the pleiotropic transcriptional activator PrfA, belonging to the Crp/Fnr family of transcription regulators (5). PrfA activates a cluster of L. monocytogenes virulence genes, including prfA, plcA, hly, mpl, actA, plcB, inlA, inlB, inlC, and hpt (6), and, thus, is regarded as a master or central virulence regulator (7). In addition, the presence and utilization of different carbohydrates has a significant impact on the virulence of L. monocytogenes (8). For example, metabolizable unphosphorylated sugars, cellobiose, and other fermentable sugars have been shown to inhibit the expression of PrfA-dependent virulence genes in L. monocytogenes. In fact, PrfA activity depends on a fully functional carbohydrate phosphotransferase (PTS) phosphorylation cascade (9). Although PrfA fulfills a central role in the virulence regulation of L. monocytogenes, several other important regulators have been identified and found to contribute to the Listeria virulence regulatory network, such as the stress-responsive alternative sigma factor σB (10), a response regulator of a two‐component system named VirR (11), the RNA-binding protein Hfq (12), and transcriptional repressors MogR (12), DegU, and GmaR (13).

Previously, our research group found, using orthology analysis, that a member of the LysR-type transcriptional regulators (LTTRs) (LMOf2365_0522) was present in pathogenic strains (EGD-e and F2365) but absent from nonpathogenic Listeria innocua strain CLIP1182 and L. monocytogenes strain HCC23 (14). The LMOf2365_0522 gene is composed of 302 amino acids and shares sequence similarity with members of the LTTRs. The family of LTTRs is the most abundant family of prokaryotic DNA-binding proteins, and these transcription factors can function as either activators or repressors of gene expression (15). The basic structure of LTTR family members includes an HTH domain at the N terminus, which is essential for binding target DNA and, thus, is crucial for its activity as a transcriptional regulator, whereas the C terminus possesses the regulatory domains 1 and 2, which are coinducer binding sites (16, 17) and exhibit low amino acid conservation. Despite their importance, no Listeria LTTRs have been characterized, and very little is known about the role of LTTRs in Listeria. The aim of the present study was to determine the role of this protein in L. monocytogenes virulence together with the identification of its regulon members.

RESULTS

The loss of LysR does not impact growth in rich or minimal medium.

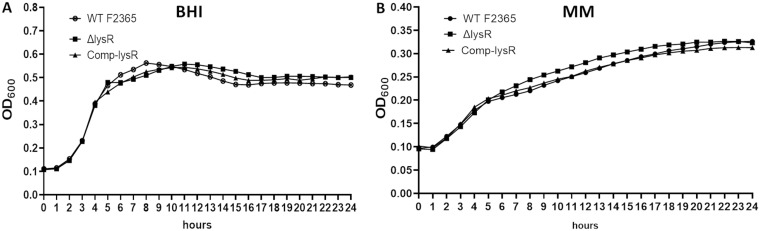

The LMOf2365_0522 gene encodes the putative LysR-type transcriptional regulator found in an L. monocytogenes pathogenic strain (F2365) but absent from nonpathogenic strains. To gain insight into the function and role of lysR, an F2365ΔlysR strain containing an in-frame deletion in the LMOf2365_0522 was constructed by allelic exchange (18). To determine whether lysR gene deletion would influence bacterial growth, the growth rates of F2365ΔlysR and wild-type strains were analyzed in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth, as enriched medium, or in minimal medium (MM). The F2365ΔlysR strain exhibited growth curves similar to those of the wild-type strain in BHI broth or MM (Fig. 1). In addition, the cell wall of the F2365ΔlysR strain seemed to be intact, as the mutant strain exhibited no significant difference in sensitivity to lysozyme or treatment with penicillin (data not shown).

FIG 1.

F2365ΔlysR strain exhibits normal growth patterns in BHI broth, as enriched medium (A), and MM (B). Bacterial growth was determined by optical density measurements at 600 nm. All growth data are the results from three independent experiments. The growth assay was conducted with wild-type F2365, F2365ΔlysR, and complement strains.

LysR contributes to L. monocytogenes cellular adhesion and invasion.

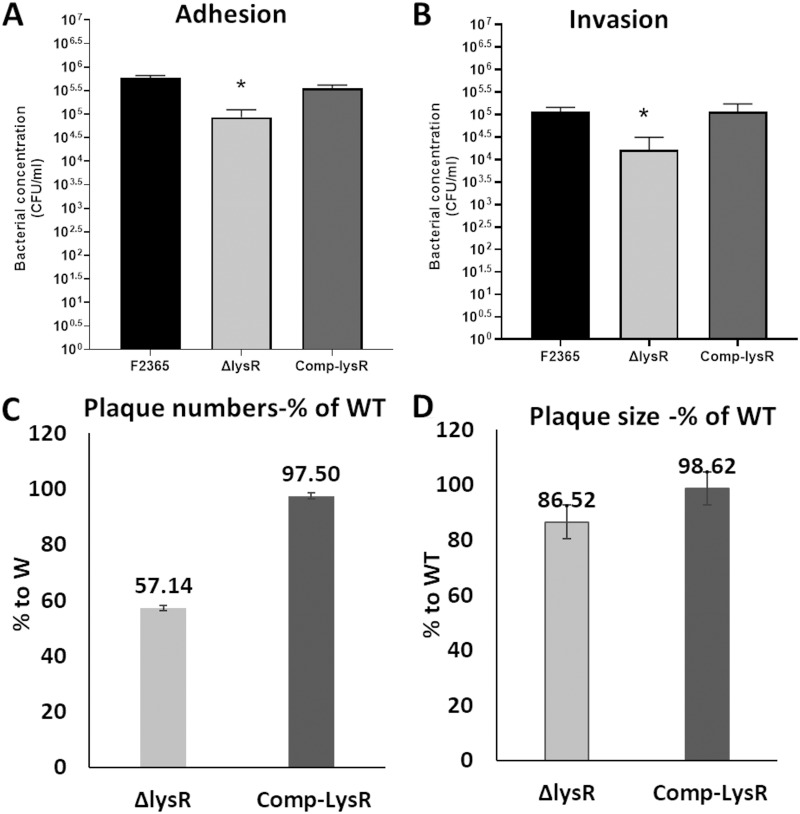

Cellular adhesion and invasion are crucial steps in L. monocytogenes pathogenesis and for bacterial crossing of the intestinal epithelial barrier. Therefore, we investigated the importance of lysR in Listeria adhesion and invasion using Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cell lines. The F2365ΔlysR strain exhibited approximately 0.7-log and 0.9-log reductions in adhesion to and invasion of Caco-2 cells compared with levels for the parent strain, F2365 (Fig. 2A and B, respectively). These differences were statistically (P < 0.05) significant. Complementation of the mutations restored adhesion and invasion properties.

FIG 2.

F2365ΔlysR strain showed reduction in adhesion (A), invasion (B), plaque number (C), and plaque size (D) with respect to the wild type. Adherence and invasion were performed with Caco-2 cells at an MOI of 10 bacteria to 1 Caco-2 cell. The experiment was performed three independent times with four replicates. Data represent mean numbers of CFU from four replicates. Error bars reflect standard errors from each means. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) compared to the wild type. Plaque assays were performed with mouse L2 fibroblasts at an MOI of 10 bacteria to 1 fibroblast cell. The plaque number and plaque size were determined 96 h postinfection. The experiment was repeated 3 independent times. At least 10 plaques were measured each time. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means. The wild-type strain was set at 100%.

The ability of the F2365ΔlysR strain to invade cells, replicate, and spread cell to cell was analyzed using the plaque formation assays in fibroblast cells (19). The mean number of plaques formed by cells infected with the F2365ΔlysR strain was significantly (P < 0.05) lower than that of cells infected with parental strain F2365 and the complement strain, with an average of 42.86% reduction in plaque numbers observed with the F2365ΔlysR strain (Fig. 2C). The reduction in the total numbers of plaques is consistent with an adhesion/invasion defect for the F2365ΔlysR mutants. Moreover, the plaques formed by cells infected with the F2365ΔlysR strain were significantly smaller (13.48% reduction in plaques size) than those infected by the wild type (Fig. 2D). These findings indicate an important contribution of LysR to cellular invasion and suggest an additional defect exists that reduces plaque size, such as defects in bacterial intracellular replication and/or cell-to-cell spread.

LysR contributes to L. monocytogenes virulence in vivo.

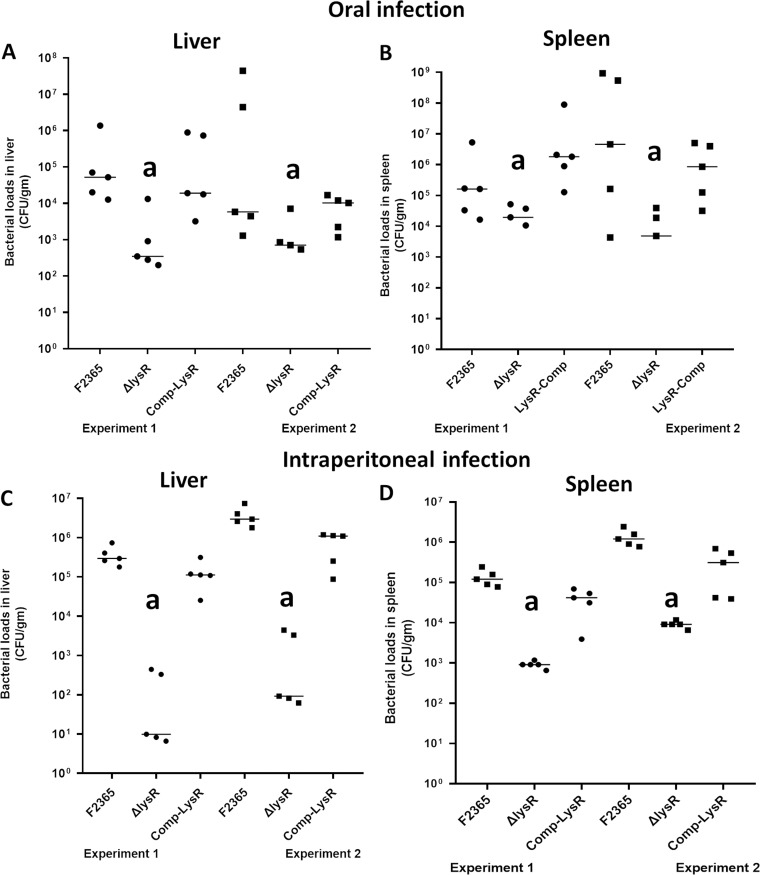

Given that the deletion of lysR has an effect on adhesion, invasion, and possibly cell-to-cell spread, we predicted that LysR would similarly show defects in mouse infection models. To determine whether lysR plays a role in L. monocytogenes virulence in vivo, the bacterial burdens of the F2365ΔlysR and wild-type strains in liver and spleen were assessed following oral and intraperitoneal (i.p.) infection of BALB/c mice. In the case of oral infection, bacterial burdens of the wild-type F2365 strain in spleen and liver were found to be significantly (P < 0.05) higher than those of the F2365ΔlysR strain. Compared to the parental strain F2365, reduction in bacterial loads in liver and spleen were 3.69 log and 3.58 log, respectively (Fig. 3A and B). There was no significant difference in bacterial load between parental strain F2365 and the complementary strain in which lysR was restored. Following i.p. infection, bacterial loads in liver and spleen were reduced about 3.6 log and 2.2 log, respectively, in mice infected with the F2365ΔlysR strain compared with those infected with the wild-type strain (Fig. 3C and D). These differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference between the parental strain F2365 and the complemented strain.

FIG 3.

Strain lacking lysR is attenuated for virulence in a mouse model following oral (A and B) and intraperitoneal (C and D) infections. Mice (5 mice per group) were infected orally or intraperitoneally with 5.9 × 107 or 1 × 105 CFU/ml. The number of CFU in liver and spleen was determined by serial dilution and plating on BHI plates. Each dot represents the bacterial concentration in one mouse. Median numbers for each strain are indicated by horizontal lines. Data were analyzed using a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. Data from two independent experiments (n = 5) are shown. Letter a, significant difference (P < 0.05) from the wild type.

To compare disease induced by the F2365ΔlysR and wild-type F2365 strains, histological analysis was performed on liver and spleen tissue collected from orally infected mice. Livers and spleens in mice infected with the F2364 strain had severe to mild/moderate pathological lesions. No severe to mild lesions were observed in the liver and spleen tissues of mice infected with the F2365ΔlysR strain (see Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). Taken together, these results indicate a significant role for LysR in L. monocytogenes pathogenesis.

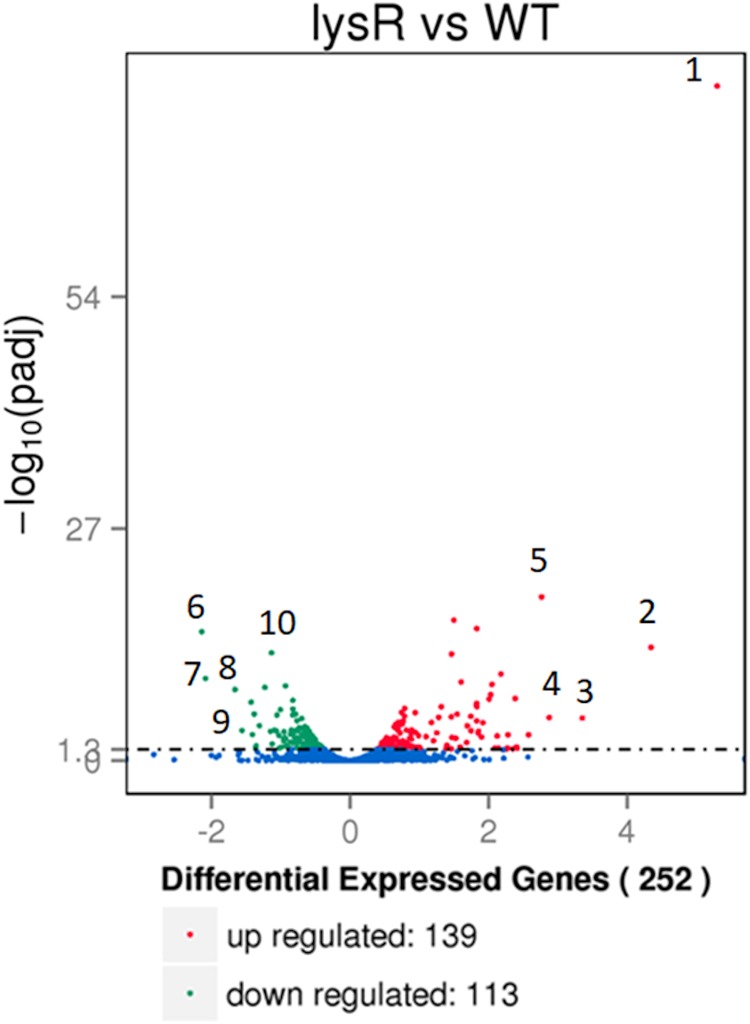

Transcriptome analysis of F2365ΔlysR and F2365 strains indicates the extensive impact of LysR on L. monocytogenes gene expression.

Given that LTTR family members are known to positively and/or negatively regulate transcription at global genetic levels and the observation that LysR is required for bacterial pathogenesis, we examined the regulatory role played by LysR in L. monocytogenes during growth in J774A.1 macrophage cell lines (Fig. 4). Macrophage cells were infected at a range of multiplicities of infection (MOI) from 1 to 10 CFU, and bacterial RNA was harvested at 4 h postinfection. A total of 252 genes were found to be significantly differentially expressed (P < 0.05). Of these, 139 were upregulated and 113 were downregulated in the F2365ΔlysR strain compared to levels in the wild type (Fig. 4), indicating that LysR acts as both an activator and repressor of transcription. The most upregulated (20) and downregulated (18) genes are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. These included genes encoding products such as ABC transporters, proteins required for motility and quorum sensing, and transcriptional regulators. A notable number of gene products had roles relating to bacterial metabolism, including starch and sucrose metabolism, glycerolipid metabolism, fructose and mannose metabolism, and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis. In addition, gene products relating to cationic antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) resistance and two-component signaling systems were identified, as were products necessary for beta-lactam resistance and peptidoglycan biosynthesis and for genes of unknown function. The diversity and number of genes directly or indirectly regulated by LysR indicate the broad impact of this regulator on L. monocytogenes physiology.

FIG 4.

Volcano plot highlighting the differential expression genes modulated by J774A.1 macrophage cells at 4 h of infection by F2365ΔlysR and wild-type strains at an MOI range from 1 to 10. The fold change in expression of each gene is plotted against mean gene expression. Upregulated genes are plotted in red, and downregulated genes are in green. Numbers 1 to 5 represent the top upregulated genes, and 6 to 10 represent the top downregulated genes. Number 1 is type I 3-dehydroquinate dehydratase 1 (aroD). Number 2 is the DUF5067 domain-containing protein. Number 3 is a hypothetical protein. Number 4 is a hypothetical protein. Number 5 is an ABC transporter protein (extracellular solute-binding protein/arabinogalactan oligomer/maltooligosaccharide transport). Number 6 is an activator of the mannose operon, transcriptional antiterminator. Number 7 is mannosylglycerate hydrolase. Number 8 is PTS fructose transporter subunit IIC. Number 9 is an ABC transporter permease. Number 10 is a PspC domain-containing protein.

TABLE 1.

Most upregulated genes in the F2365ΔlysR strain compared to levels in the F2365 strain

| Locus tag | Protein name | Log2 fold change | P value | Corrected P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABC transporter | ||||

| LMOf2365_0190 | Multiple sugar transport system permease protein | 1.17 | 5.81E−07 | 3.65E−05 |

| LMOf2365_0191 | Putative multiple sugar transport system protein | 1.39 | 8.83E−04 | 1.62E−02 |

| LMOf2365_0267 | Extracellular solute-binding protein/arabinogalactan oligomer/maltooligosaccharide transport | 2.57 | 3.00E−05 | 9.76E−04 |

| LMOf2365_0268 | Sugar ABC transporter permease (arabinogalactan oligomer/maltooligosaccharide transport) | 2.03 | 1.19E−10 | 2.14E−08 |

| LMOf2365_0269 | Sugar ABC transporter permease (arabinogalactan oligomer/maltooligosaccharide transport) | 1.85 | 9.30E−06 | 3.84E−04 |

| LMOf2365_2830 | Multiple sugar transport system substrate-binding protein | 2.18 | 2.74E−13 | 8.80E−11 |

| LMOf2365_0570 | ABC transporter substrate-binding protein, iron complex transport system substrate-binding protein | 2.12 | 4.44E−05 | 1.35E−03 |

| LMOf2365_2828 | Carbohydrate ABC transporter permease, multiple sugar transport system permease protein | 2.05 | 5.52E−12 | 1.33E−09 |

| LMOf2365_2829 | Sugar ABC transporter permease, multiple sugar transport system permease protein | 2.01 | 4.37E−10 | 7.01E−08 |

| LMOf2365_0044 | SIS domain-containing protein glucoselysine-6-phosphate deglycase | 2.39 | 3.41E−10 | 5.78E−08 |

| LMOf2365_2732 | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | 1.01 | 6.54E−04 | 1.26E−02 |

| Starch and sucrose metabolism and PTS | ||||

| LMOf2365_0388 | Glycoside hydrolase family 1 protein | 0.87 | 9.02E−04 | 1.64E−02 |

| LMOf2365_0389 | PTS system, beta-glucoside-specific, IIC component; PTS system, cellobiose-specific IIC component | 0.89 | 1.33E−04 | 3.17E−03 |

| LMOf2365_0043 | PTS sugar transporter subunit IIC PTS system, cellobiose-specific IIC component | 1.83 | 1.63E−09 | 2.24E−07 |

| LMOf2365_0270 | Alpha-glucosidase (malL-2) | 1.68 | 3.85E−04 | 7.91E−03 |

| LMOf2365_0271 | Sucrose phosphorylase | 1.85 | 2.01E−05 | 6.99E−04 |

| LMOf2365_1271 | Trehalose-6-phosphate hydrolase or alpha,alpha-phosphotrehalase | 0.86 | 9.65E−05 | 2.47E−03 |

| LMOf2365_2772 | Beta-glucosidase (bglX-2) | 1.02 | 2.51E−03 | 3.42E−02 |

| Glycerolipid metabolism, glycolysis/ gluconeogenesis | ||||

| LMOf2365_0364 | d-Threitol dehydrogenase | 2.26 | 4.14E−03 | 4.76E−02 |

| LMOf2365_0365 | Ribose 5-phosphate isomerase B′′ | 2.41 | 2.82E−03 | 3.65E−02 |

| LMOf2365_0366 | Triosephosphate isomerase | 2.35 | 3.66E−03 | 4.35E−02 |

| LMOf2365_0367 | Dihydroxyacetone kinase subunit L (dhaL) | 2.40 | 1.73E−03 | 2.58E−02 |

| LMOf2365_0368 | Dihydroxyacetone kinase subunit (dhaK) | 2.14 | 2.61E−03 | 3.51E−02 |

| LMOf2365_0369 | Hypothetical protein | 2.09 | 2.72E−03 | 3.59E−02 |

| LMOf2365_0371 | PTS-dependent dihydroxyacetone kinase phosphotransferase subunit (dhaM) | 1.46 | 3.66E−03 | 4.35E−02 |

| LMOf2365_1055 | Glycerol kinase (glpK1) | 1.90 | 6.26E−05 | 1.82E−03 |

| Quorum sensing | ||||

| LMOf2365_0155 | ABC transporter permease | 1.06 | 6.00E−08 | 5.09E−06 |

| LMOf2365_1830 | Signal recognition particle-docking protein FtsY | 0.89 | 1.86E−03 | 2.72E−02 |

| LMOf2365_0058 | Putative accessory gene regulator protein D (agrD) | 0.49 | 9.17E−04 | 1.65E−02 |

| LMOf2365_0059 | Putative accessory gene regulator protein C (agrC) | 0.49 | 9.17E−04 | 1.65E−02 |

| Flagellar assembly | ||||

| LMOf2365_0749 | Flagellar basal body M-ring protein FliF | 0.86 | 1.21E−03 | 2.02E−02 |

| LMOf2365_0750 | Flagellar motor switch protein FliG | 0.99 | 1.72E−03 | 2.58E−02 |

| LMOf2365_0751 | Flagellar assembly protein H FliH | 0.83 | 1.22E−03 | 2.02E−02 |

| LMOf2365_0726 | FliC/FljB family flagellin | 0.71 | 5.00E−04 | 9.96E−03 |

| Phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis: LMOf2365_0521 | Type I 3-dehydroquinate dehydratase 1 (aroD) | 5.30 | 1.04E−82 | 3.01E−79 |

| Pentose phosphate pathway | ||||

| LMOf2365_0362 | Transketolase (tkt-1) | 2.27 | 2.73E−03 | 3.59E−02 |

| LMOf2365_1054 | Putative transketolase, C-terminal subunit (tkt-2) | 2.28 | 2.91E−05 | 9.66E−04 |

| Transcriptional factor | ||||

| LMOf2365_0041 | ROK family protein | 1.74 | 8.72E−08 | 7.00E−06 |

| LMOf2365_0189 | ROK family transcriptional regulator | 1.50 | 4.49E−20 | 4.32E−17 |

| LMOf2365_0042 | Glycosyl hydrolase; glycosyl hydrolase, family 9 | 1.55 | 4.16E−08 | 3.88E−06 |

| LMOf2365_0575 | Hypothetical protein (oxidoreductase, putative) | 1.25 | 1.65E−05 | 5.97E−04 |

| LMOf2365_RS08335 | Phage transcriptional regulator, ArpU family | 1.74 | 1.12E−5 | 1.12E−05 |

| Anaerobic regulatory protein: #x2003;LMOf2365_0626 | Crp/Fnr family transcriptional regulator | 1.32 | 4.40E−09 | 5.29E−07 |

| Alanine aspartate and glutamate metabolism and pyrimidine metabolism | ||||

| LMOf2365_1864 | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase small subunit (carA) | 1.42 | 1.11E−09 | 1.61E−07 |

| Call wall binding and surface protein | ||||

| LMOf2365_0614 | WxL domain-containing protein | 1.12 | 6.19E−04 | 1.20E−02 |

| LMOf2365_2495 | LysM peptidoglycan-binding domain-containing protein | 1.83 | 4.12E−09 | 5.17E−07 |

| PTS | ||||

| LMOf2365_1056 | PTS beta-glucoside transporter subunit IIBCA (bglP) | 1.28 | 1.21E−07 | 9.66E−04 |

| LMOf2365_1900 | Trypsin-like serine protease | 1.60 | 2.68E−12 | 7.04E−10 |

| Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | ||||

| LMOf2365_2826 | Sugar phosphate isomerase/epimerase YcjR | 1.83 | 3.60E−07 | 2.41E−05 |

| LMOf2365_2827 | Zinc-binding alcohol dehydrogenase | 1.75 | 8.01E−06 | 3.40E−04 |

| Sucrose phosphorylase: LMOf2365_2831 | Sucrose phosphorylase or sucrose glucosyltransferase, disaccharide glucosyltransferase | 1.83 | 5.95E−19 | 4.29E−16 |

| Miscellaneous and unknown | ||||

| LMOf2365_0646 | DUF5067 domain-containing protein | 4.34 | 1.37E−16 | 9.30E−20 |

| LMOf2365_0648 | Hypothetical protein | 2.76 | 6.44E−23 | 2.64E−06 |

| LMOf2365_0649 | DUF1398 domain-containing protein | 0.94 | 2.65E−08 | 1.28E−03 |

| LMOf2365_0650 | Sulfite exporter TauE/SafE family protein | 0.99 | 4.15E−05 | 8.14E−06 |

| LMOf2365_1028 | Hypothetical protein | 2.87 | 1.27E−07 | 2.14E−03 |

| LMOf2365_1052 | Fucose isomerase | 1.47 | 8.03E−05 | 9.30E−20 |

| LMOf2365_2313 | LLM class flavin-dependent oxidoreductase | 1.35 | 0.00114 | 0.019598 |

| LMOf2365_0526 | DUF896 domain-containing protein | 1.92 | 6.47E−07 | 3.98E−05 |

| LMOf2365_2209 | DUF4870 domain-containing protein | 1.01 | 1.11E−08 | 1.19E−06 |

| LMOf2365_2824 | Glycoside hydrolase family 65 protein | 1.69 | 1.65E−06 | 9.01E−05 |

| LMOf2365_2825 | Gfo/Idh/MocA family oxidoreductase | 1.59 | 1.73E−03 | 2.58E−02 |

TABLE 2.

Most downregulated genes in the F2365ΔlysR strain compared to levels in the F2365 strain

| Locus tag | Description | Log2 fold change | P value | Corrected P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fructose and mannose metabolism | ||||

| LMOf2365_0115 | PTS mannose/fructose/sorbose transporter family subunit IID | −0.95 | 1.18E−05 | 4.48E−04 |

| LMOf2365_RS02125 | PTS sugar transporter subunit IIA | −1.15 | 1.00E−05 | 3.94E−04 |

| LMOf2365_RS02130 | PTS fructose transporter subunit IIB | −1.36 | 3.08E−03 | 3.89E−02 |

| LMOf2365_RS02135 | PTS fructose transporter subunit IIC | −1.66 | 2.81E−11 | 5.41E−09 |

| LMOf2365_0421 | Mannosylglycerate hydrolase | −2.09 | 9.61E−13 | 2.78E−10 |

| LMOf2365_0422 | Activator of the mannose operon, transcriptional antiterminator | −2.14 | 1.71E−18 | 9.88E−16 |

| CAMP resistance, two-component system | ||||

| LMOf2365_0991 | d-Alanyl-lipoteichoic acid biosynthesis protein DltD | −1.03 | 3.79E−05 | 1.19E−03 |

| LMOf2365_0992 | d-Alanine-poly(phosphoribitol) ligase subunit DltC | −1.31 | 1.54E−06 | 8.55E−05 |

| LMOf2365_0993 | d-Alanyl-lipoteichoic acid biosynthesis protein DltB | −1.09 | 6.47E−06 | 2.92E−04 |

| LMOf2365_0994 | d-Alanine-poly(phosphoribitol) ligase subunit DltA | −0.86 | 2.64E−05 | 8.96E−04 |

| LMOf2365_0995 | Teichoic acid d-Ala incorporation-associated protein DltX | −0.79 | 1.08E−04 | 2.69E−03 |

| LMOf2365_0312 | Serine protease Do | −0.83 | 5.33E−08 | 4.67E−06 |

| Beta-lactam resistance: LMOf2365_2262 | Penicillin-binding protein 1A | −1.09 | 1.31E−05 | 4.91E−04 |

| ABC transporter permease: LMOf2365_2148 | ABC transporter permease | −1.56 | 7.05E−06 | 3.13E−04 |

| Membrane protein: LMOf2365_2457 | Phage holin family protein | −1.23 | 1.47E−11 | 3.03E−09 |

| Uncharacterized proteins with unknown function | ||||

| LMOf2365_2411 | YxeA family protein | −1.38 | 4.40E−08 | 3.97E−06 |

| LMOf2365_0633 | Hypothetical protein | −1.06 | 8.50E−06 | 3.56E−04 |

| LMOf2365_2458 | PspC domain-containing protein | −1.41 | 2.79E−05 | 9.36E−04 |

| LMOf2365_2459 | PspC domain-containing protein | −1.13 | 6.90E−16 | 2.85E−13 |

Functional classification of differentially expressed genes.

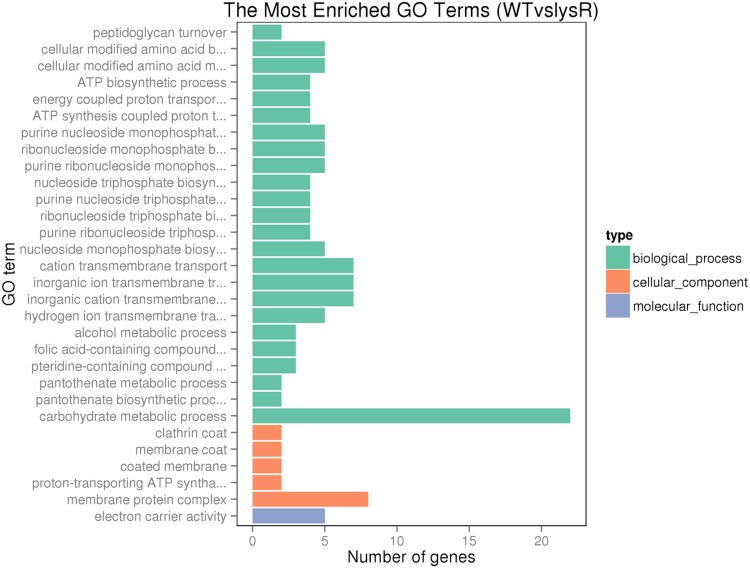

To better understand the impact of LysR on L. monocytogenes gene expression, gene ontology (GO) analysis was conducted to functionally categorize differentially expressed genes into three categories, as shown in Fig. 5: biological process, cellular component, and molecular function. Among the enriched categories in the biological process component were carbohydrate metabolic process, inorganic cation transmembrane transport, peptidoglycan turnover, cellular modified amino acid biosynthesis and metabolism, and ATP biosynthetic process. In the cellular component category, membrane protein complex, coated membrane, and proton-transporting ATPase were among the most enriched. In the molecular function category, electron carrier activity was the most enriched group (Fig. 5).

FIG 5.

GO functional enrichment analysis for all differentially expressed genes. The colors represent different GO types.

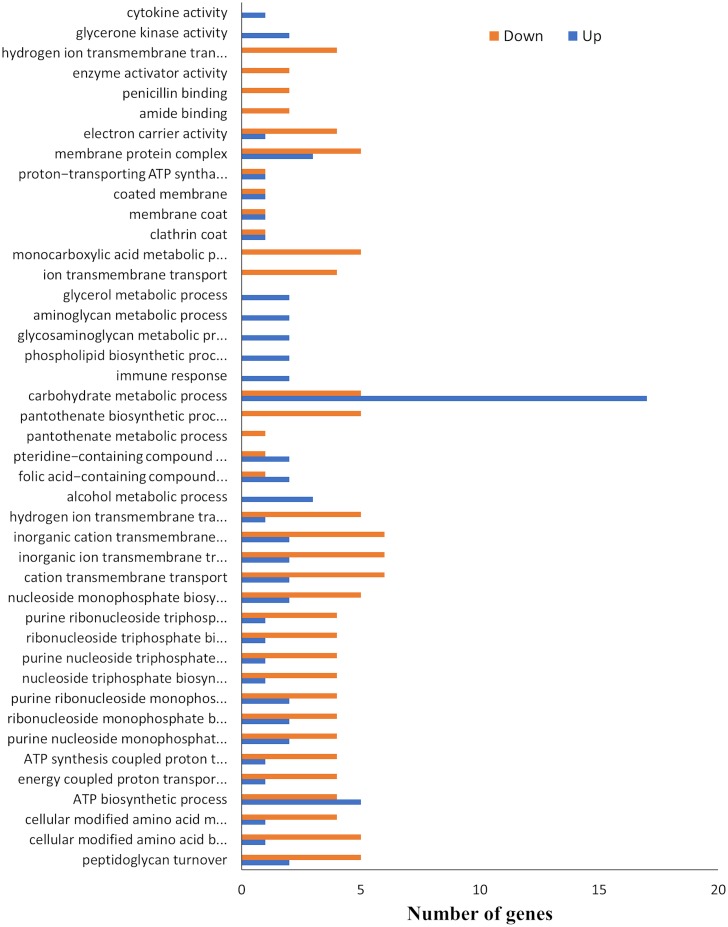

The main GO categories for upregulated and downregulated differentially expressed genes are shown in Fig. 6. The main categories represented among the upregulated genes were those involved in the carbohydrate metabolic process (17 genes), ATP biosynthetic process (5 genes), alcohol metabolic process (3 genes), glycerol metabolic process (2 genes), aminoglycan metabolic process (2 genes), glycosaminoglycan metabolic process (2 genes), phospholipid biosynthetic process (2 genes), and immune response (2). In contrast, the main categories represented among the downregulated genes were genes associated with ion transmembrane transport (5 genes), monocarboxylic acid metabolic process (6 genes), proton transport (4 genes), hydrogen transport (4 genes), inorganic cation transmembrane transport (6 genes), inorganic ion transmembrane transport (6 genes), cation transmembrane transport (6 genes), cellular modified amino acid metabolism (5 genes), and cellular modified amino biosynthesis (5 genes).

FIG 6.

GO categories for upregulated and downregulated genes based on differentially expressed genes in the RNA-seq.

Pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes.

Differentially expressed genes were mapped to reference pathways in the KEGG database to further identify the significantly enriched metabolic pathways or signal transduction pathways between the F2365ΔlysR strain and wild-type F2365. There were 21 upregulated pathways and 24 downregulated pathways (Tables 3 and 4). Some pathways were shared in both upregulated and downregulated genes, especially those including microbial metabolism in diverse environments (10 genes upregulated and 7 genes downregulated), biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (16 genes upregulated and 9 genes downregulated), biosynthesis of antibiotics (13 genes upregulated and 5 genes downregulated), fructose and mannose metabolism (4 genes upregulated and 4 genes downregulated), phosphotransferase system (PTS) (5 genes upregulated and 4 genes downregulated), carbon metabolism (9 genes upregulated and 4 genes downregulated), and metabolic pathways (28 genes upregulated and 21 genes downregulated).

TABLE 3.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for upregulated genes

| Term | Sample no. | P value | Corrected P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABC transporters | 7 | 9.51E−02 | 4.22E−01 |

| Starch and sucrose metabolism | 6 | 3.41E−04 | 1.60E−02 |

| Metabolic pathways | 28 | 1.08E−01 | 4.22E−01 |

| Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites | 16 | 7.35E−02 | 3.84E−01 |

| Biosynthesis of antibiotics | 13 | 5.44E−02 | 3.84E−01 |

| Microbial metabolism in diverse environments | 10 | 1.03E−01 | 4.22E−01 |

| Carbon metabolism | 9 | 1.97E−02 | 2.63E−01 |

| Quorum sensing | 3 | 2.60E−01 | 6.82E−01 |

| Biosynthesis of amino acids | 8 | 2.10E−01 | 6.18E−01 |

| Glycerolipid metabolism | 4 | 5.61E−03 | 1.32E−01 |

| Flagellar assembly | 4 | 3.42E−02 | 3.21E−01 |

| Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis | 5 | 5.93E−02 | 3.84E−01 |

| PTS | 5 | 3.21E−01 | 6.30E−01 |

| Pyruvate metabolism | 4 | 7.15E−02 | 3.84E−01 |

| Fructose and mannose metabolism | 4 | 2.40E−01 | 6.18E−01 |

| Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | 3 | 2.23E−02 | 2.63E−01 |

| Pentose phosphate pathway | 3 | 2.10E−01 | 6.18E−01 |

| Pyrimidine metabolism | 3 | 3.12E−01 | 6.30E−01 |

| RNA degradation | 2 | 1.42E−01 | 5.12E−01 |

| Homologous recombination | 2 | 2.33E−01 | 6.18E−01 |

| Methane metabolism | 2 | 2.80E−01 | 6.18E−01 |

TABLE 4.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for downregulated genes

| Term | Gene no. | P value | Corrected P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two-component system | 10 | 1.87E−05 | 7.29E−04 |

| CAMP resistance | 5 | 4.77E−05 | 9.30E−04 |

| Metabolic pathways | 21 | 2.76E−01 | 6.82E−01 |

| Fructose and mannose metabolism | 4 | 1.54E−01 | 6.00E−01 |

| Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites | 9 | 5.28E−01 | 6.82E−01 |

| Microbial metabolism in diverse environments | 7 | 2.64E−01 | 6.82E−01 |

| Biosynthesis of antibiotics | 5 | 7.78E−01 | 8.42E−01 |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | 4 | 2.35E−02 | 1.63E−01 |

| Beta-lactam resistance | 2 | 5.36E−02 | 2.62E−01 |

| PTS | 4 | 3.74E−01 | 6.82E−01 |

| Carbon metabolism | 4 | 4.06E−01 | 6.82E−01 |

| Pantothenate and coenzyme A biosynthesis | 3 | 2.64E−02 | 1.63E−01 |

| Ribosome | 3 | 5.14E−01 | 6.82E−01 |

| d-Alanine metabolism | 2 | 2.24E−02 | 1.63E−01 |

| Cyanoamino acid metabolism | 2 | 2.24E−02 | 1.63E−01 |

| Beta-alanine metabolism | 2 | 2.92E−02 | 1.63E−01 |

| Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | 2 | 1.28E−01 | 5.53E−01 |

| Alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism | 2 | 2.02E−01 | 6.82E−01 |

| Methane metabolism | 2 | 2.15E−01 | 6.82E−01 |

| Glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism | 2 | 3.19E−01 | 6.82E−01 |

| Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | 2 | 3.58E−01 | 6.82E−01 |

| Pyrimidine metabolism | 2 | 4.79E−01 | 6.82E−01 |

| Purine metabolism | 2 | 5.86E−01 | 7.14E−01 |

| Biosynthesis of amino acids | 2 | 9.48E−01 | 9.57E−01 |

On the other hand, genes in some pathways were either only upregulated or only downregulated. The primary pathways for upregulated differentially expressed genes were starch and sucrose metabolism (6 genes), glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (5 genes), glycerolipid metabolism (4 genes), flagellar assembly (4 genes), pyruvate metabolism (4 genes), citrate cycle (tricarboxylic acid [TCA] cycle; 3 genes), pentose phosphate pathway (3 genes), pyrimidine metabolism (3 genes), and RNA degradation (2 genes). Two-component systems (10 genes), CAMP resistance (10 genes), and oxidative phosphorylation (4 genes) were represented only among the downregulated differentially expressed genes.

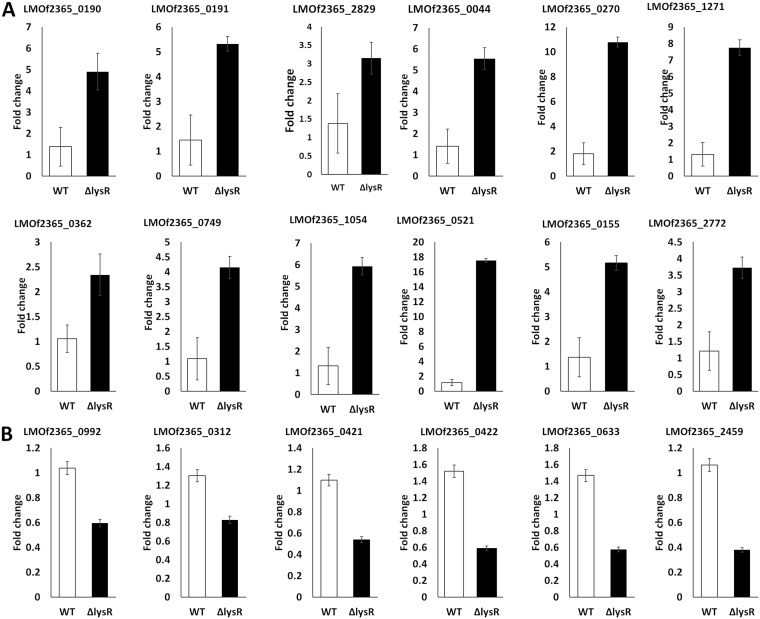

Verification of gene expression using qRT-PCR.

Twelve upregulated and six downregulated genes were selected from the list based on functional categories and pathways to verify their expression by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR). The expression profiles of the examined genes were consistent with the transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) results (Fig. 7), although observed fold changes differed in qRT-PCR and RNA-seq data, which may reflect sensitivity and specificity differences between qRT-PCR and RNA-sequencing technology (21).

FIG 7.

RT-PCR analyses of selected differentially expressed genes. (A) Upregulated genes; (B) downregulated genes. The data represent means ± standard errors from four biological replicates.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the infection of Caco-2 cells, fibroblast plaque assays, and a mouse model were used to determine the contribution of lysR to L. monocytogenes virulence. The F2365ΔlysR strain displayed attenuation in mice following oral and i.p. infection. Attenuation in cases of oral infection may include a contribution from defects in adherence to and penetration of the intestinal epithelium and/or systemic effects. The i.p. route allows Listeria to disseminate systemically via the lymphatic system and blood, but it bypasses the need for invasion of the intestine, as occurs in oral infection (22). Previous work showed that the disruption of LTTR family members caused a loss of virulence. For example, MvfR of P. aeruginosa reduced virulence in mice and plants (23, 24). ShvR of Burkholderia cenocepacia reduced virulence in a mammalian and plant model of infection (25). Several LTTRs are known to play a role in host-pathogen interactions by controlling the expression of virulence genes. Examples of bacterial virulence genes under LTTR are protease and type 2 secretion system (T2SS) genes of B. cenocepacia (ShvR) (25), ADP-ribosyltransferase toxin of Yersinia enterocolitica, the T3SS of P. aeruginosa (MexT) (26, 27), and a pathogenicity island (SPI-1) in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (LeuO) (28). In the present study, given the number of genes whose expression is affected by the deletion of lysR, it is difficult to attribute the virulence defects to any one type of gene or pathway, and it may be that the virulence effect stems from the misregulation of several sets of genes.

In the present study, the transcriptome data revealed 139 upregulated and 113 downregulated protein-coding genes in the F2365ΔlysR strain, including carbohydrate transport and metabolism, amino acid metabolism, flagellar assembly, the phosphotransferase system (PTS), cell wall binding and surface proteins, beta-lactam resistance, and two-component systems. Previously, it was shown that members of the LTTRs regulate the expression of a variety of genes, including those involved in virulence (29, 30), quorum sensing (25), motility (31), metabolism, and environmental recognition (32, 33). aphA of Vibrio cholerae controls the expression of nearly 300 genes, including genes involved in type III secretion systems, flagellum synthesis, pilus production, and members of the quorum-sensing circuit (34). ampR in Pseudomonas aeruginosa acts as a global transcriptional factor gene whose regulon includes genes for beta-lactamases, proteases, quorum sensing, and other virulence factors (35, 36). Clearly, the LysR family members appear to wield broad impacts on multiple pathways of gene expression.

L. monocytogenes can utilize glycerol as a source of carbon through a complex set of genes involved in the metabolism of glycerol (37). Indeed, glycerol and three other carbon sugars serve as the primary carbon source used by L. monocytogenes within the cytosol of infected host cells (38). In the current study, transcriptome analysis showed the upregulation of genes associated with glycerol metabolism and glycerol uptake (glpK, dhaL, dhaK, and dhaM). glpK encodes glycerol kinase and plays a role in converting glycerol to glycerol-3 phosphate. Dihydroxyacetone (dha) plays a role in phosphorylation and subsequent metabolization of glycerol (39). dhaKLM genes are part of an extended operon, and the entire operon was highly upregulated in the F2365ΔlysR strain compared to that in F2365. This operon encodes five other proteins that previously were shown to be involved in different metabolic pathways and metabolism (40). This result implies that the repression of lysR activity facilitates the uptake and utilization of glycerol as a carbon source by directly regulating glpK and dhaKLM genes.

Flagellar motility in Listeria plays an important role in facilitating adherence to abiotic and cellular surfaces and is important for biofilm formation and cellular invasion (41, 42). RNA-seq analysis revealed that the deletion of the lysR gene resulted in the upregulation of four genes involved in motility, including fliF, fliG, fliH, and fliC-fljB. A previous study in Campylobacter jejuni showed that the lysR regulator is involved in the upregulation of flagellum biogenesis (flaA, flaB, flgG2, flgH, fliD, and fliS) (43), whereas in Escherichia coli K-12, the LysR-type transcriptional regulator QseD represses motility (44). Despite these changes in transcript levels, motility in vitro of the F2365ΔlysR strain was unchanged compared to that of the wild-type strain (data not shown). Moreover, flagellar motility in Listeria differs from other bacterial species, because in L. monocytogenes flagellar motility is temperature dependent and is regulated by a distinctly different mechanism than the well-described regulation in Gram-negative bacteria. The regulation of flagellar synthesis genes in Listeria is controlled by sigma factors as well as by specific regulators (such as flgM) (45).

In the present study, RNA-seq revealed that the deletion of lysR led to the downregulation of an operon encoding fructose-specific components of the phosphotransferase transport system (PTS) permease. This operon contains three genes encoding the fructose-specific PTS, which consists of IIA, IIB, and IIC components. The PTS serves as a sugar transport system in bacteria, and there are approximately 30 copies of different PTS present in the genome of L. monocytogenes (46). A previous study demonstrated that an IIA component (LMOf2365_0442) is required for virulence in L. monocytogenes strain F2365 (47). Besides carbohydrate transporters, the PTS also regulates numerous cellular processes, including carbon catabolite repression (CCR) (48). Some PTSs also have been associated with stress response and biofilm formation (49). Therefore, it was suggested that metabolizable sugars that are taken up by the phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP)-dependent PTS, like glucose, mannose, and especially cellobiose, are negatively correlated with the activity of prfA (50–52). Results from the present study suggest that lysR indirectly modulates (interferes with) prfA activity through the decreased uptake of fructose, mannose, or other sugar components.

Another major finding in the present study was the downregulation of the gene encoding an activator of the mannose operon, a transcriptional antiterminator. The PTS encoded by the mannose permease (mpt) is the principal glucose transporter in L. monocytogenes (53–55). In Listeria species, mannose PTS permease has been shown to play a central role in class IIa bacteriocin resistance (56), CCR (57, 58), and downregulation of virulence gene expression in glucose medium (9, 59, 60). The downregulation of mpt may be an adaptable mechanism of Listeria to reduce the consumption of glucose as a carbon source in the F2365ΔlysR strain.

Another important finding in the present study was the downregulation of the clpP gene, encoding the serine protease Do. clpP is essential for the intracellular growth of L. monocytogenes in vivo and plays a major role in the induction of anti-Listeria protective immunity (20). An L. monocytogenes mutant with a deletion in the clpP gene failed to grow in macrophages during the early phase of infection (8 h). In the absence of clpP, the virulence of L. monocytogenes also was sharply reduced, and this behavior was due to the reduction in functional listeriolysin O (LLO), explaining the inability of the bacteria to escape the phagosomal compartment in macrophages (61). Accordingly, we speculate that the reduced virulence and defect in intracellular growth of the F2365ΔlysR strain is caused in part by clpP repression.

The present study represented transcriptome profiling of the L. monocytogenes F2365ΔlysR strain using RNA-seq technology. Thus, transcriptomic changes observed were adaptive responses of L. monocytogenes to the deletion of lysR in the context of bacterial growth within macrophages. Data presented in this study further extend our knowledge of the role of lysR in L. monocytogenes and also provide insight into the regulatory network of this bacterium. Because most LTTRs activate the transcription of target promoters only in the presence of small signaling molecules (coinducers), the identification of the coinducer molecule required for lysR expression needs to be examined in a further study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 5. Escherichia coli DH5α was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) (Difco Laboratories) broth and agar. Listeria strains were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Difco) at 37°C. Human enterocyte-like Caco-2 (TIB37; ATCC) and fibroblast (CRL-2648; ATCC) cell lines were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (ATCC, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA) and 1% glutamine. Cultures were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 under humidified conditions.

TABLE 5.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Bacterial strain, plasmid, or primer | Description or sequence | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | Competent cells | Invitrogen |

| L. monocytogenes | ||

| F2365 | Wild-type serotype 4b strain | 72 |

| F2365ΔlysR | F2365ΔlysR mutant strain | This study |

| F2365ΔlysR::pPL2-lysR | F2365ΔlysR::pPL2-lysR complemented strain | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pHoss1 | 8,995 bp, pMAD::secY antisense, ΔbgaB | 18 |

| pPL2 | 6,123 bp, PSA attPP, Chlr | 62 |

| pLmΔlysR | pHoss1::ΔlysR | This study |

| pPL2-lysR | pPL2::lysR | This study |

| Primers | ||

| LysR_F02 | AAGTCGACCTTGGCGTTCACTTGGTTCTA | SalI |

| LysR_R938 | GGATGGGTGCTCTTTACTCGT | |

| LysR_F833 | ACGAGTAAAGAGCACCCATCCTAACATCAATTTGCCCAGGAG | |

| LysR_R02 | AACCATGGCACACAAAGAAATGCCAGTTG | NcoI |

| LysR_seq | CTTGCCAGGGAGAGCATCGTT | |

| LysR_Comp-F01 | AAAGAGCTCGAGCACCCATCCTATATTCAGC | SacI |

| LysR_Comp-R01 | AAAGTCGACCTGCTTCAAGAATTATTTTCGTTT | SalI |

Construction of ΔlysR mutant and complemented strains.

The lysR gene (LMOf2365_0522) was targeted for in-frame deletion using an allelic exchange technique as previously published (18). The sequences of primers used for the construction and validation of the mutant are listed in Table 5. The mutant strain was complemented by inserting a copy of the wild-type gene with its promoter region using the pPL2 shuttle integration vector (62).

Growth assay.

Growth of wild-type F2365, F2365ΔlysR, and complemented strains in BHI broth and minimal medium (MM) (63) was analyzed. Bacterial curves were generated by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) on a multimode reader (BioTek Cytation 5) every hour after a brief agitation for 24 h at 37°C. The growth assays were conducted in three independent experiments, and each experiment was run with six replicates.

MIC determination.

The MICs of penicillin and lysozyme were determined using a broth microdilution assay in 96-well plates. Bacteria were grown overnight, and then approximately 105 cells were used to inoculate 200 μl BHI broth containing 2-fold dilutions of penicillin or lysozyme. The starting concentrations were 0.06 μg/ml for penicillin and 0.1 mg/ml for lysozyme. The OD600 readings were determined after incubating the 96-well plates for 24 h at 37°C with shaking.

Adherence, invasion, and plaque assays.

Adherence and invasion of the F2365ΔlysR mutant to Caco-2 epithelial cells were evaluated as described previously (64). In brief, monolayer Caco-2 cells were grown into 24-well tissue culture plates at 105 cells per well. For adhesion assay, cells were infected with bacteria (106 CFU) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 bacterial cells per Caco-2 cell and incubated at 37°C for 1 h, after which the medium was removed. Infected cells then were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to eliminate nonadherent bacteria. Adherent Listeria organisms were lysed with 0.5% Triton X-100 and serially diluted and plated on BHI agar for enumeration. For the invasion assay, bacteria were added to the Caco-2 cell monolayer to yield an MOI of 10 bacteria per Caco-2 cell and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Infected cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated in medium containing gentamicin (10 μg/ml) for 2 h to kill extracellular bacteria. Cells then were washed three times with PBS and lysed using 0.5% Triton X-100. Appropriate dilutions of the lysates were spread on BHI agar. All infections were performed three independent times, and four replicates were performed for each infection.

Plaque assays with murine fibroblast cell (ATCC CRL-2648) monolayers were conducted as described previously (19). Briefly, fibroblast cells were grown in DMEM in six-well tissue culture plates until confluence. Confluent monolayers were infected with bacteria for 1 h. DMEM agar containing 10 μg/ml gentamicin then was added to each well. The plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 4 days. Living cells were visualized by adding an additional overlay consisting of DMEM, 0.5% agarose, and 0.1% neutral red and incubating the dishes overnight.

Murine infection.

The virulence of the F2365ΔlysR strain was compared with that of L. monocytogenes strain F2365 and a complemented strain in BALB/c mice through oral and intraperitoneal (i.p.) routes as previously described (65, 66). Animal studies were performed under a protocol (18-508) approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Mississippi State University. Female 8- to 12-week-old BALB/c mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory and were housed in 4 cages (5 mice/cage) according to treatment group. Animals were maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions and provided with food and water ad libitum. In the case of oral infections, the OD600 was adjusted so that approximately 5.9 × 107 CFU/ml of each bacterial strain was orally infused by gavage needle in each mouse. For i.p. infection, mice were injected with 1 × 105 CFU/ml bacteria suspended in 100 μl of sterile saline. Control mice were inoculated with sterile saline. Animals were monitored daily for signs of disease and mortality. For oral infection studies, mice were euthanized on day 5 postinfection. For i.p. infection studies, mice reached a moribund stage earlier and were euthanized on day 3 postinfection. After euthanasia, spleen and liver tissues were aseptically removed, weighed, and homogenized in sterile saline. Suspensions then were diluted and plated onto BHI agar plates to determine the number of CFU per gram. Portions of the liver and spleen from orally infected mice were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histopathological analysis. After fixation, tissues were embedded in paraffin, followed by sectioning at 5 μm and staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Gram stain as previously described (67). The animal experiment was repeated independently twice, and bacterial strains were tested using groups of five animals.

Infection of J774A.1 cells by F2365ΔlysR strain.

A murine macrophage cell line, J774A.1, was grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were passaged when they reached 70% to 80% confluence and seeded onto 12-well plates 2 days before infection. Overnight cultures of F2365ΔlysR and F2365 strains were harvested by centrifugation, and the pellet was resuspended in PBS. Cells were washed twice with Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) and covered for 1 h with DMEM containing a bacterial strain. The average MOI was calculated to range from 1 to 10. After the cells were washed once with HBSS, extracellular bacteria were removed by adding 0.5 ml DMEM containing 10 μg/ml gentamicin. After 4 h of incubation, the infected J774A.1 cells were washed again with HBSS and then lysed in 1 ml cold Triton X-100 (0.1%). RNA extraction was performed as described below.

RNA extraction.

Total RNA was isolated from macrophage cell lines infected with Listeria (F2365 or F2365ΔlysR strain) using the FastRNA spin kit for microbes and the FastPrep-24 instrument (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) by following the manufacturer’s instructions. For each strain, total RNA was isolated from four independent biological replicates. Genomic DNA was eliminated from the total RNA by using on-column DNase treatment with an RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The quantity and quality of total RNA were analyzed using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) by measuring the OD260/OD280 ratio. A Ribo-Zero magnetic kit for Gram-positive bacteria (Epicentre) was used to remove rRNAs, and then a fragmentation buffer was added to fragment mRNAs. Before library construction, the concentration of RNA was normalized by using specific ScriptSeq kits (Epicentre).

Library preparation for strand-specific transcriptome sequencing.

Library construction and sequencing were performed by Novogene Corporation, Inc., Centre for Genomic Research (CGR). Briefly, strand-specific RNA-seq was performed as previously described (68). Using random hexamers as primers (Promega), mRNA fragments were reverse transcribed to single-stranded cDNAs. After the synthesis of single-stranded cDNAs, first-strand buffer (Invitrogen), deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dTTP was replaced by dUTP), DNA polymerase I, and RNase H were applied, and samples were incubated at 25°C for 2 min to synthesize complementary cDNA strands. Double-stranded cDNAs were purified using AMPure XP (Biolabs) beads according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Resultant double-stranded cDNAs were end repaired, polyadenylated, ligated with adapter sequences, and size selected using AMPure XP beads. Uracil-containing strands then were degraded with USER Enzyme (NEB, USA), and the remaining strands were amplified using PCR and purified using AMPure XP beads. The cDNA libraries then were subjected to sequencing using the HiSeq platform (Illumina). For each strain, four independent biological replicates were sequenced.

Gene annotation, alignment, and analysis.

Before analyzing data, raw reads were filtered to remove reads containing adapters or low-quality reads. The resulting reads were used for mapping sequences to the genome of a Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b strain using Bowtie2 (69). Transcriptomic analysis was conducted using the Bioconductor Edge R analysis package (70). Transcripts for each sample were quantified and normalized as the number of reads per kilobase per million reads (RPKM). Four replicate RPKM values for each sample were standardized on the basis of their mean transcript values and were used to assess gene expression and fold change differences in expression between the F2365 and ΔlysR strains. To minimize false-positive results, a stringent cutoff false discovery rate (FDR) of 1 was applied when identifying differentially expressed genes of the wild-type compared to the mutant strains.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses.

GO enrichment analysis was conducted by GOseq (73), which is based on Wallenius noncentral hypergeometric distribution. GO covers molecular functions, biological processes, and cellular components. The differentially expressed gene list was mapped to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) to identify significantly enriched metabolic pathways or signal transduction pathways.

Verification of gene expression by qRT-PCR.

To validate gene expression and RNA-seq data, qRT-PCR was performed on the same RNAs as those used for transcriptome experiments. Primers and gene information are listed in Table 6. Primers were designed with IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies) software. Purified RNA (5 μg) was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis (Thermo Scientific kit), which was performed with the following steps: 10 min at 25°C followed by 30 min at 50°C, with reaction termination at 85°C for 5 min. The product of the first-strand cDNA synthesis was diluted 50 times for use in qRT-PCR. qRT-PCR was performed in a 20-μl reaction volume containing 5 μl of cDNA, 10 μl of SYBR green real-time PCR master mix (Roche Diagnostic GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), 0.6 μl of gene‐specific primers (10 μM), and 3.8 μl water. Amplification and detection of specific products were performed with the Mx3000P real-time PCR system (Stratagene) with the following cycle profile: initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. The expression of each gene was normalized against the expression of the housekeeping gene, 16S rRNA, before comparative analysis. Further, DNA melting curve analysis at the end of each run ensured that the desired amplicon was detected and that no secondary products were amplified. For each gene, triplicate assays were done. Expression levels of tested genes were quantified by the relative quantitative method (2−△△CT) (71).

TABLE 6.

Primers used in qRT-PCR

| Gene locus tag | Primer sequence (5′–3′) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | |

| LMOf2365_0190 | CTCGTTTGGAAATGGCTGTTC | ACCAATATCTTTCCACGCACTAG |

| LMOf2365_0191 | TGGCTGGTTGGATTCGTATG | GTAAAATGATTGGCACCGTCC |

| LMOf2365_2829 | TGCAAACGGTCGATAAGTCG | AAGTACCGGCATAATCGCTG |

| LMOf2365_0044 | TGGCAAGAGGAATTCGCTAC | GCCCATGCATAAACGCTTC |

| LMOf2365_0270 | ATCAGCCGGGAATTGAAGAG | CAAACACCATACGGAAATGACC |

| LMOf2365_1271 | TTATCATTCGGCAACCCTCC | GCGTTTCCACATCCACATAATC |

| LMOf2365_0362 | GATTCGTTTGGTATGTCTGGC | GCTCCGTCAAGTTCTCTACAG |

| LMOf2365_0749 | TGTCGTTGTCTGGGTTGATC | TCTTCGGTTGTCATATTAGGCG |

| LMOf2365_1054 | AAGTGATTCAAGAGGATCCGC | GGCAATCCCAGTCTCAACTAG |

| LMOf2365_0521 | TGCTGGAGACGTACTAACTTTAC | CATTGCGGAGCCAAATACTTC |

| LMOf2365_0155 | ATGACCCTAATGCTCTTTCCG | CATCGCAAATACACCGACAAG |

| LMOf2365_2772 | GTAGACCAATCGCTATCCCAG | CCGAAAAGAACCTCAGCAATC |

| LMOf2365_0992 | TGCTTGATTCTATGGCTACGG | ATTTCAGGAGTAGCCCATTCG |

| LMOf2365_0312 | AAGTGGTAACGGGAATGGTG | TCACCATTATCCCAAGCGAC |

| LMOf2365_0421 | GTAATGACAGAGGGCGTACG | AACGATTGACTCACCGGAAG |

| LMOf2365_0422 | GGTAGCCACTTATCAGCTCAG | GATTTCGATTTTGTATCCCGCG |

| LMOf2365_0633 | CATTACTCCCGCGATTATCTGG | TCATTACAACTACACCAGCGAC |

| LMOf2365_2459 | GAAGACCAAGACCAGAAAATGC | AGTAAAGGAACGGAAAGTCGC |

| 16S rRNA | CAAGCGTTGTCCGGATTTATTG | GCACTCCAGTCTTCCAGTTT |

Statistical analysis.

The dot plots and median values of bacterial numbers in each mouse were generated using GraphPad Prism 8 software. For in vivo experiments, a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was used to detect the statistical significance in bacterial load in liver and spleen of infected mice with F2365, 2365ΔlysR, and complemented strains. Fold changes were calculated for each gene using the 2−ΔΔCT formula and used for statistical analysis to determine significant differences in gene expression between F2365ΔlysR and F2365 strains. The statistical significance of differences was evaluated with one-way analysis of variance using PROC GLM in SAS (v 9.4; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant in all analyses.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Laboratory Animal Resources and Care Unit at Mississippi State University for animal and veterinary care. We also thank Basant Gomaa, and Michelle Banes, for their help in mouse experiments. We also thank John Harkness and Stephen Pruett for review of the manuscript.

This study was supported by the Center for Biomedical Research Excellence in Pathogen-Host Interactions, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health (P20 GM103646-06).

H.A., M.L.L., and A.K. designed the study. H.A. constructed the mutant and complemented strains and performed the RNA-seq. H.A., R.R., O.O., and A.C. performed mouse experiments and real-time PCR. A.C. and A.K.O. performed the histopathological analysis. L.N. performed the plaque assay. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vázquez-Boland JA, Kuhn M, Berche P, Chakraborty T, Domínguez-Bernal G, Goebel W, González-Zorn B, Wehland J, Kreft J. 2001. Listeria pathogenesis, and molecular virulence determinants. Clin Microbiol Rev 14:584–640. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.3.584-640.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson MA, Roy SL, Jones JL, Griffin PM. 2011. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States–major pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis 17:7–15. doi: 10.3201/eid1701.p11101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cossart P. 2011. Illuminating the landscape of host-pathogen interactions with the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:19484–19491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112371108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camejo A, Carvalho F, Reis O, Leitao E, Sousa S, Cabanes D. 2011. The arsenal of virulence factors deployed by Listeria monocytogenes to promote its cell infection cycle. Virulence 2:379–394. doi: 10.4161/viru.2.5.17703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lampidis R, Gross R, Sokolovic Z, Goebel W, Kreft J. 1994. The virulence regulator protein of Listeria ivanovii is highly homologous to PrfA from Listeria monocytogenes and both belong to the Crp-Fnr family of transcription regulators. Mol Microbiol 13:141–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milohanic E, Glaser P, Coppée J-Y, Frangeul L, Vega Y, Vázquez-Boland JA, Kunst F, Cossart P, Buchrieser C. 2003. Transcriptome analysis of Listeria monocytogenes identifies three groups of genes differently regulated by PrfA. Mol Microbiol 47:1613–1625. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freitag NE, Port GC, Miner MD. 2009. Listeria monocytogenes–from saprophyte to intracellular pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:623–628. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreft J, Vazquez-Boland JA. 2001. Regulation of virulence genes in Listeria. Int J Med Microbiol 291:145–157. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herro R, Poncet S, Cossart P, Buchrieser C, Gouin E, Glaser P, Deutscher J. 2005. How seryl-phosphorylated HPr inhibits PrfA, a transcription activator of Listeria monocytogenes virulence genes. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 9:224–234. doi: 10.1159/000089650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliver HF, Orsi RH, Wiedmann M, Boor KJ. 2010. Listeria monocytogenes σB has a small core regulon and a conserved role in virulence but makes differential contributions to stress tolerance across a diverse collection of strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:4216–4232. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00031-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandin P, Fsihi H, Dussurget O, Vergassola M, Milohanic E, Toledo-Arana A, Lasa I, Johansson J, Cossart P. 2005. VirR, a response regulator critical for Listeria monocytogenes virulence. Mol Microbiol 57:1367–1380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christiansen JK, Larsen MH, Ingmer H, Søgaard-Andersen L, Kallipolitis BH. 2004. The RNA-binding protein Hfq of Listeria monocytogenes: role in stress tolerance and virulence. J Bacteriol 186:3355–3362. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.11.3355-3362.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamp HD, Higgins DE. 2009. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of the GmaR antirepressor governs temperature-dependent control of flagellar motility in Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol 74:421–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06874.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paul D, Steele C, Donaldson JR, Banes MM, Kumar R, Bridges SM, Arick M, Lawrence ML. 2014. Genome comparison of Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4a strain HCC23 with selected lineage I and lineage II L. monocytogenes strains and other Listeria strains. Genom Data 2:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.gdata.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schell MA. 1993. Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol 47:597–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stec E, Witkowska-Zimny M, Hryniewicz MM, Neumann P, Wilkinson AJ, Brzozowski AM, Verma CS, Zaim J, Wysocki S, Bujacz GD. 2006. Structural basis of the sulphate starvation response in E. coli: crystal structure and mutational analysis of the cofactor-binding domain of the Cbl transcriptional regulator. J Mol Biol 364:309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang WM, Zhang JJ, Jiang X, Chao H, Zhou NY. 2015. Transcriptional activation of multiple operons involved in para-nitrophenol degradation by Pseudomonas sp. strain WBC-3. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:220–230. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02720-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdelhamed H, Lawrence ML, Karsi A. 2015. A novel suicide plasmid for efficient gene mutation in Listeria monocytogenes. Plasmid 81:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones S, Portnoy DA. 1994. Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis in a strain expressing perfringolysin O in place of listeriolysin O. Infect Immun 62:5608–5613. doi: 10.1128/IAI.62.12.5608-5613.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaillot O, Bregenholt S, Jaubert F, Di Santo JP, Berche P. 2001. Stress-induced ClpP serine protease of Listeria monocytogenes is essential for induction of listeriolysin O-dependent protective immunity. Infect Immun 69:4938–4943. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.8.4938-4943.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, Shen B, Du P, Wang N, Wang J, Li J, Sun A. 2017. Transcriptomic analysis of the response of Pseudomonas fluorescens to epigallocatechin gallate by RNA-seq. PLoS One 12:e0177938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pitts MG, D’Orazio S. 2018. A comparison of oral and intravenous mouse models of listeriosis. Pathogens 7:E13. doi: 10.3390/pathogens7010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao H, Krishnan G, Goumnerov B, Tsongalis J, Tompkins R, Rahme LG. 2001. A quorum sensing-associated virulence gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a LysR-like transcription regulator with a unique self-regulatory mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:14613–14618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251465298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deziel E, Gopalan S, Tampakaki AP, Lepine F, Padfield KE, Saucier M, Xiao G, Rahme LG. 2005. The contribution of MvfR to Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis and quorum sensing circuitry regulation: multiple quorum sensing-regulated genes are modulated without affecting lasRI, rhlRI or the production of N-acyl-L-homoserine lactones. Mol Microbiol 55:998–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Grady EP, Nguyen DT, Weisskopf L, Eberl L, Sokol PA. 2011. The Burkholderia cenocepacia LysR-type transcriptional regulator ShvR influences expression of quorum-sensing, protease, type II secretion, and afc genes. J Bacteriol 193:163–176. doi: 10.1128/JB.00852-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Axler-DiPerte GL, Miller VL, Darwin AJ. 2006. YtxR, a conserved LysR-like regulator that induces expression of genes encoding a putative ADP-ribosyltransferase toxin homologue in Yersinia enterocolitica. J Bacteriol 188:8033–8043. doi: 10.1128/JB.01159-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian Z-X, Fargier E, Mac Aogáin M, Adams C, Wang Y-P, O'Gara F. 2009. Transcriptome profiling defines a novel regulon modulated by the LysR-type transcriptional regulator MexT in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nucleic Acids Res 37:7546–7559. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Espinosa E, Casadesus J. 2014. Regulation of Salmonella enterica pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) by the LysR-type regulator LeuO. Mol Microbiol 91:1057–1069. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russell DA, Byrne GA, O'Connell EP, Boland CA, Meijer WG. 2004. The LysR-type transcriptional regulator VirR is required for expression of the virulence gene vapA of Rhodococcus equi ATCC 33701. J Bacteriol 186:5576–5584. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.17.5576-5584.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doty SL, Chang M, Nester EW. 1993. The chromosomal virulence gene, chvE, of Agrobacterium tumefaciens is regulated by a LysR family member. J Bacteriol 175:7880–7886. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7880-7886.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heroven AK, Dersch P. 2006. RovM, a novel LysR-type regulator of the virulence activator gene rovA, controls cell invasion, virulence and motility of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 62:1469–1483. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hartmann T, Zhang B, Baronian G, Schulthess B, Homerova D, Grubmüller S, Kutzner E, Gaupp R, Bertram R, Powers R, Eisenreich W, Kormanec J, Herrmann M, Molle V, Somerville GA, Bischoff M. 2013. Catabolite control protein E (CcpE) is a LysR-type transcriptional regulator of tricarboxylic acid cycle activity in Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem 288:36116–36128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.516302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takao M, Yen H, Tobe T. 2014. LeuO enhances butyrate-induced virulence expression through a positive regulatory loop in enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 93:1302–1313. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kovacikova G, Skorupski K. 1999. A Vibrio cholerae LysR homolog, AphB, cooperates with AphA at the tcpPH promoter to activate expression of the ToxR virulence cascade. J Bacteriol 181:4250–4256. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.14.4250-4256.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kong K-F, Jayawardena SR, Indulkar SD, del Puerto A, Koh C-L, Høiby N, Mathee K. 2005. Pseudomonas aeruginosa AmpR is a global transcriptional factor that regulates expression of AmpC and PoxB β-lactamases, proteases, quorum sensing, and other virulence factors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:4567–4575. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4567-4575.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balasubramanian D, Schneper L, Merighi M, Smith R, Narasimhan G, Lory S, Mathee K. 2012. The regulatory repertoire of Pseudomonas aeruginosa AmpC β-lactamase regulator AmpR includes virulence genes. PLoS One 7:e34067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joseph B, Mertins S, Stoll R, Schar J, Umesha KR, Luo Q, Muller-Altrock S, Goebel W. 2008. Glycerol metabolism and PrfA activity in Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol 190:5412–5430. doi: 10.1128/JB.00259-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bruno JC Jr, Freitag NE. 2010. Constitutive activation of PrfA tilts the balance of Listeria monocytogenes fitness towards life within the host versus environmental survival. PLoS One 5:e15138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ouellette M, Makkay AM, Papke RT. 2013. Dihydroxyacetone metabolism in Haloferax volcanii. Front Microbiol 4:376. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Domain F, Bina XR, Levy SB. 2007. Transketolase A, an enzyme in central metabolism, derepresses the marRAB multiple antibiotic resistance operon of Escherichia coli by interaction with MarR. Mol Microbiol 66:383–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Neil HS, Marquis H. 2006. Listeria monocytogenes flagella are used for motility, not as adhesins, to increase host cell invasion. Infect Immun 74:6675–6681. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00886-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lemon KP, Higgins DE, Kolter R. 2007. Flagellar motility is critical for Listeria monocytogenes biofilm formation. J Bacteriol 189:4418–4424. doi: 10.1128/JB.01967-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dufour V, Li J, Flint A, Rosenfeld E, Rivoal K, Georgeault S, Alazzam B, Ermel G, Stintzi A, Bonnaure-Mallet M, Baysse C. 2013. Inactivation of the LysR regulator Cj1000 of Campylobacter jejuni affects host colonization and respiration. Microbiology 159:1165–1178. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.062992-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Habdas BJ, Smart J, Kaper JB, Sperandio V. 2010. The LysR-type transcriptional regulator QseD alters type three secretion in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli and motility in K-12 Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 192:3699–3712. doi: 10.1128/JB.00382-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gründling A, Burrack LS, Bouwer HGA, Higgins DE. 2004. Listeria monocytogenes regulates flagellar motility gene expression through MogR, a transcriptional repressor required for virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:12318–12323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404924101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stoll R, Goebel W. 2010. The major PEP-phosphotransferase systems (PTSs) for glucose, mannose and cellobiose of Listeria monocytogenes, and their significance for extra- and intracellular growth. Microbiology 156:1069–1083. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.034934-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Y, Yoo BB, Hwang CA, Suo Y, Sheen S, Khosravi P, Huang L. 2017. LMOf2365_0442 encoding for a fructose specific PTS permease IIA may be required for virulence in L. monocytogenes strain F2365. Front Microbiol 8:1611. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deutscher J, Francke C, Postma PW. 2006. How phosphotransferase system-related protein phosphorylation regulates carbohydrate metabolism in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 70:939–1031. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00024-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu MC, Chen YC, Lin TL, Hsieh PF, Wang JT. 2012. Cellobiose-specific phosphotransferase system of Klebsiella pneumoniae and its importance in biofilm formation and virulence. Infect Immun 80:2464–2472. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06247-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gilbreth SE, Benson AK, Hutkins RW. 2004. Catabolite repression and virulence gene expression in Listeria monocytogenes. Curr Microbiol 49:95–98. doi: 10.1007/s00284-004-4204-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Milenbachs AA, Brown DP, Moors M, Youngman P. 1997. Carbon-source regulation of virulence gene expression in Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol 23:1075–1085. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2711634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Renzoni A, Klarsfeld A, Dramsi S, Cossart P. 1997. Evidence that PrfA, the pleiotropic activator of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes, can be present but inactive. Infect Immun 65:1515–1518. doi: 10.1128/IAI.65.4.1515-1518.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dalet K, European Listeria Genome Consortium, Cenatiempo Y, Cossart P, Héchard Y. 2001. A σ54-dependent PTS permease of the mannose family is responsible for sensitivity of Listeria monocytogenes to mesentericin Y105. Microbiology 147:3263–3269. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-12-3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stoll R, Mertins S, Joseph B, Muller-Altrock S, Goebel W. 2008. Modulation of PrfA activity in Listeria monocytogenes upon growth in different culture media. Microbiology 154:3856–3876. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/018283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vadyvaloo V, Arous S, Gravesen A, Hechard Y, Chauhan-Haubrock R, Hastings JW, Rautenbach M. 2004. Cell-surface alterations in class IIa bacteriocin-resistant Listeria monocytogenes strains. Microbiology 150:3025–3033. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xue J, Hunter I, Steinmetz T, Peters A, Ray B, Miller KW. 2005. Novel activator of mannose-specific phosphotransferase system permease expression in Listeria innocua, identified by screening for pediocin AcH resistance. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:1283–1290. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1283-1290.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arous S, Buchrieser C, Folio P, Glaser P, Namane A, Hebraud M, Hechard Y. 2004. Global analysis of gene expression in an rpoN mutant of Listeria monocytogenes. Microbiology 150:1581–1590. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26860-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xue J, Miller KW. 2007. Regulation of the mpt operon in Listeria innocua by the ManR protein. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:5648–5652. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00052-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deutscher J, Herro R, Bourand A, Mijakovic I, Poncet S. 2005. Ser-HPr–a link between carbon metabolism and the virulence of some pathogenic bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta 1754:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mertins S, Joseph B, Goetz M, Ecke R, Seidel G, Sprehe M, Hillen W, Goebel W, Muller-Altrock S. 2007. Interference of components of the phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system with the central virulence gene regulator PrfA of Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol 189:473–490. doi: 10.1128/JB.00972-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gaillot O, Pellegrini E, Bregenholt S, Nair S, Berche P. 2000. The ClpP serine protease is essential for the intracellular parasitism and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol 35:1286–1294. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lauer P, Chow MY, Loessner MJ, Portnoy DA, Calendar R. 2002. Construction, characterization, and use of two Listeria monocytogenes site-specific phage integration vectors. J Bacteriol 184:4177–4186. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.15.4177-4186.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Premaratne RJ, Lin WJ, Johnson EA. 1991. Development of an improved chemically defined minimal medium for Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 57:3046–3048. doi: 10.1128/AEM.57.10.3046-3048.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cowart RE, Lashmet J, McIntosh ME, Adams TJ. 1990. Adherence of a virulent strain of Listeria monocytogenes to the surface of a hepatocarcinoma cell line via lectin-substrate interaction. Arch Microbiol 153:282–286. doi: 10.1007/bf00249083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bou Ghanem EN, Jones GS, Myers-Morales T, Patil PD, Hidayatullah AN, D'Orazio SEF. 2012. InlA promotes dissemination of Listeria monocytogenes to the mesenteric lymph nodes during food borne infection of mice. PLoS Pathog 8:e1003015. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Olier M, Pierre F, Rousseaux S, Lemaître J-P, Rousset A, Piveteau P, Guzzo J. 2003. Expression of truncated internalin A is involved in impaired internalization of some Listeria monocytogenes isolates carried asymptomatically by humans. Infect Immun 71:1217–1224. doi: 10.1128/iai.71.3.1217-1224.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brown RC, Hopps HC. 1973. Staining of bacteria in tissue sections: a reliable gram stain method. Am J Clin Pathol 60:234–240. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/60.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Parkhomchuk D, Borodina T, Amstislavskiy V, Banaru M, Hallen L, Krobitsch S, Lehrach H, Soldatov A. 2009. Transcriptome analysis by strand-specific sequencing of complementary DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 37:e123. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. 2009. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol 10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. 2010. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schefe JH, Lehmann KE, Buschmann IR, Unger T, Funke-Kaiser H. 2006. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR data analysis: current concepts and the novel “gene expression’s CT difference” formula. J Mol Med 84:901–910. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nelson KE, Fouts DE, Mongodin EF, Ravel J, DeBoy RT, Kolonay JF, Rasko DA, Angiuoli SV, Gill SR, Paulsen IT, Peterson J, White O, Nelson WC, Nierman W, Beanan MJ, Brinkac LM, Daugherty SC, Dodson RJ, Durkin AS, Madupu R, Haft DH, Selengut J, Van Aken S, Khouri H, Fedorova N, Forberger H, Tran B, Kathariou S, Wonderling LD, Uhlich GA, Bayles DO, Luchansky JB, Fraser CM. 2004. Whole genome comparisons of serotype 4b and 1/2a strains of the food-borne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes reveal new insights into the core genome components of this species. Nucleic Acids Res 32:2386–2395. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Young MD, Wakefield MJ, Smyth GK, Oshlack A. 2010. Gene ontology analysis for RNA‐seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol 11:R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.