Summary

Understanding how fungi interact with other organisms has significant medical, environmental, and agricultural implications. Nematode-trapping fungi (NTF) can switch to pathogens by producing various trapping devices to capture nematodes. Here we perform comparative genomic analysis of the NTF with four representative trapping devices. Phylogenomic reconstruction of these NTF suggested an evolutionary trend of trapping device simplification in morphology. Interestingly, trapping device simplification was accompanied by expansion of gene families encoding adhesion proteins and their increasing adhesiveness on trap surfaces. Gene expression analysis revealed a consistent up-regulation of the adhesion genes during their lifestyle transition from saprophytic to nematophagous stages. Our results suggest that the expansion of adhesion genes in NTF genomes and consequential increase in trap surface adhesiveness are likely the key drivers of fungal adaptation in trapping nematodes, providing new insights into understanding mechanisms underlying infection and adaptation of pathogenic fungi.

Subject Areas: Biological Sciences, Genomics, Evolutionary Biology

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Expansion of subtilisin, adhesion protein, and polygalacturonase gene families

-

•

Trap simplification during evolution of nematode-trapping fungi

-

•

Connection between trap simplification and expansion of adhesion genes

Biological Sciences; Genomics; Evolutionary Biology

Introduction

Fungal infections have devastated agricultural crops and contributed to severe diseases in humans and animals (Fisher et al., 2012). Plant pathogenic fungi can destroy plant tissues and result in great crop losses. Animal fungal pathogens can cause systemic and opportunistic mycoses, with two ongoing epidemics that have caused millions of deaths of amphibians (O'Hanlon et al., 2018) and bats (Kramer et al., 2019). In humans, life-threatening fungal diseases have been among the most challenging medical problems. Indeed, fungal infestations continue to rise and pose a significant threat to all plants and animals, including humans. However, fungal infections are difficult to treat, partly because fungi are evolutionarily closely related to plants and animals and many of them are not obligate pathogens but arise through adaptations from preexisting characteristics of non-parasitic lifestyles. The mechanisms underlying such adaptations are poorly understood.

Most fungal pathogens have two or more lifestyles, and they can switch to pathogenic mode under specific environmental cues (Gauthier, 2015). Therefore, understanding fungal lifestyle transition is of great significance to uncover the mechanisms underlying fungal pathogenesis. For instance, Magnaporthe oryzae can cause rice blast. Its pathogenesis starts from the attachment of conidia to plant surface and followed by conidia germination and penetration (Ebbole, 2007). M. oryzae has been a model for understanding plant-fungal interactions. The dimorphic fungus Candida albicans is a commensal of the mammalian mycoflora and the most common opportunistic pathogen of humans. Its ability to transition between yeast and hyphal form is essential for pathogenesis (Mayer et al., 2013). The insect pathogen Metarhizium anisopliae grows naturally in soils as a saprophyte and causes disease in various insects initiated by conidia germination after the adhesion of conidia to the host cuticle (Aw and Hue, 2017). However, most fungal lifestyle transitions are difficult to determine. Among the pathogenic fungi, the nematode-trapping fungi (NTF) are unique in that they have evolved specialized morphological adaptations to capture nematodes. The formation of trapping devices is the key indicator of their lifestyle transition from saprophytes to predators and thus makes them good models for studying the mechanisms of fungal pathogenesis and adaptation (Abad et al., 2008, Yang et al., 2011, Yang et al., 2012, Zhang and Hyde, 2014).

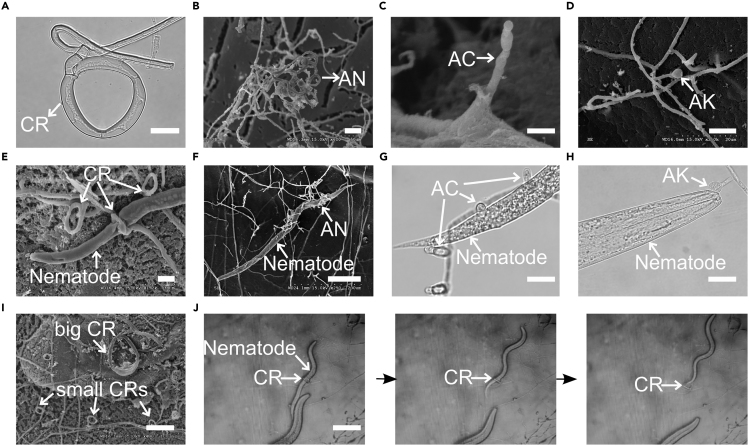

Four representative types of traps are known among the nematode-trapping fungi, including constricting ring (CR), adhesive network (AN), adhesive column (AC), and adhesive knob (AK). In CR, when triggered, the three curved ring cells swell rapidly inward and lasso the victim quickly using mechanical force (Figure 1A). Instead of mechanical forces, fungi with AN form interlocking loops by growing branching hyphae and fusing with the parent hyphae to develop adhesive networks to capture nematodes (Figure 1B). Fungi with the AC device form a string of cells with adhesive surfaces (Figure 1C). Lastly, AK is an erect stalk with an adhesive bulb at the end (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Various Trapping Devices Have Been Developed to Capture Nematodes

(A) Constricting ring developed by Drechslerella brochopaga (Scale bar, 10 μm).

(B) 3-D adhesive networks developed by Arthrobotrys oligospora (Scale bar, 20 μm).

(C) Adhesive columns developed by Dactylellina cionopagum (Scale bar, 5 μm).

(D) Adhesive knob developed by Dactylellina entomopaga (Scale bar, 10 μm).

(E) Nematode being captured by constricting ring (Scale bar, 10 μm).

(F) Nematode being captured by adhesive networks (Scale bar, 100 μm).

(G) Nematode being captured by multiple adhesive columns (Scale bar, 10 μm).

(H) Nematode being captured by one single adhesive knob (Scale bar, 10 μm).

(I) Constricting rings of various sizes were developed (Scale bar, 50 μm).

(J) Nematode escaped from the constricting rings (Scale bar, 50 μm).

CR, constricting ring; AN, adhesive network; AC, adhesive column; AK, adhesive knob. See also Tables S1 and S2.

Of the four types of nematode-trapping devices, two have had their representative genomes sequenced, including Arthrobotrys oligospora representing AN (Ji et al., 2019, Yang et al., 2011) and Monacrosporium haptotylum representing AK (Meerupati et al., 2013). Here we sequenced the genomes of three additional species, including Drechslerella brochopaga (representing CR), Dactylellina cionopagum (representing AC), and Dactylellina entomopaga (representing AK). In addition, a close relative to NTF but without a trapping device, Dactylella cylindrospora, was also sequenced for comparative analyses. The combined analysis showed that the expansion of genes encoding adhesion proteins (APs) among fungal genomes and their up-regulation during the fungal lifestyle change were responsible for the increasing adhesiveness on trap surface, driving the evolution of the nematode-trapping fungi and their adaptation in capturing nematodes using different trapping devices. The expansion of adhesion gene families has likely played very important roles during the evolution and adaptation of the predatory lifestyle by the NTF. They function in capturing nematodes, ensuring their lifestyle transition from saprophytes to predators and pathogens. Our results provide insights into the mechanisms underlying fungal pathogenesis and adaptation.

Results

The four types of nematode traps have distinct features. Morphologically, CRs are most complicated (Xue-Mei Niu and Zhang, 2011, Yang et al., 2007). They immobilize nematodes actively and mechanically by rapid swelling of three highly ordered ring cells (Figure 1E). In contrast, ANs use complex three-dimensional adhesive nets to capture nematodes (Figure 1F), whereas ACs and AKs use two-dimensional adhesive columns and simple adhesive knobs, respectively (Figures 1G and 1H). Compared with the adhesive traps, one of the limiting factors for CRs is nematode size. Fungi with different-sized CRs were likely selected to capture nematodes of various sizes (Figure 1I). However, nematodes can escape CR even after entrapment (Figure 1J). Among the four types of traps, AK is the most efficient where a single knob is often sufficient to capture large nematodes (Figure 1H).

Genome Sequencing of Nematode-Trapping Fungi

The estimated genome sizes of the sequenced NTF ranged from 35 to 43 Mb (Table S1). The GC contents were about 44%–50% (Table S2). Their gene models, ranging from 9,924 to 10,716 (Table S3), were predicted by combining ab initio prediction and evidence-based searches. The average lengths of protein-coding genes were about 1.5 kb, and each gene contained averages of 2.8–3 exons, with 2,500–3,000 genes containing only one single exon each. About 60% of the inferred proteins had matches in public databases.

Phylogenomic Analysis Reveals Simplification of Trapping Devices

Previous research based on fossil records and phylogenetic analyses suggested potential evolutionary relationships among various nematode-trapping devices (Yang et al., 2007, Yang et al., 2012). To further study the pathogenic adaptation of the nematode-trapping fungi at the genome level, the phylogenomic relationships among the representative NTF were constructed using the maximum likelihood method based on 395 conserved genes coding for orthologous proteins. These 395 genes were conserved across all the 16 genomes used in phylogenomic analysis (Table S4), including the 5 representative NTF, the close relative D. cylindrospora, 7 other pathogenic fungi, and 3 saprophytes. These orthologous genes were mostly involved in house-keeping functions. Saccharomyces cerevisiae was used as the outgroup member. The bootstrap analysis based on 1,000 replications strongly supported the tree topology (Figure 2A). The phylogenomic tree showed that the NTF and their close relative Dactylella cylindrospora belonged to a monophyletic clade and suggested an unambiguous trend during the evolution of trapping devices. Specifically, the fungal nematode-trapping ability originated from a saprophytic ancestor of Orbiliomycetes. After D. cylindrospora split at around 339 Myr ago, the organisms with the active mechanical trap (CR) emerged first, followed by those with passive adhesive traps, including the fungi developing complex 3-D adhesive networks, adhesive columns, and adhesive knobs evolved in sequence.

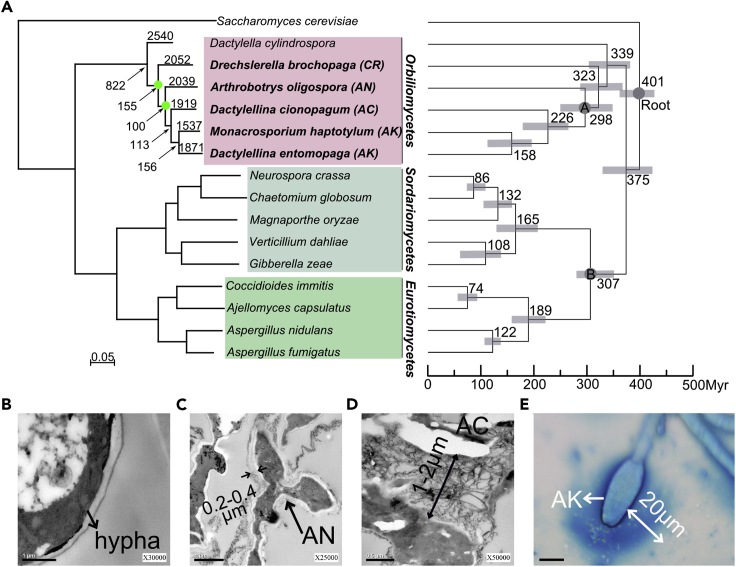

Figure 2.

Phylogenomics and Ultrastructural Analyses of Nematode-Trapping Fungi

(A) Phylogenomic tree constructed based on concatenated orthologous proteins from 16 fungal genomes using maximum-likelihood method. The numbers on the branches represent the gene numbers specific to the species; the numbers with arrows pointing to the nodes represent the numbers of orthologous genes specific to the clades. The bootstrap values are all 1,000/1,000 except two of them are 999/1,000 that are labeled with green circles. The right panel showed the estimated divergence times of the major lineages. Error bars represent the 95% highest posterior density (HPD) for a node age. Three calibrations include root node (310–420 Mya), node A (100–420 Mya), and node B (290–420 Mya) (Cracraft and Donoghue, 2004, Prieto and Wedin, 2013, Sipiczki, 2000).

(B) No obvious adhesive layer can be observed on the hyphal surfaces of A. oligospora (Scale bar, 1 μm).

(C) The thickness of adhesive layer on adhesive networks is about 0.1–0.2 μm (Scale bar, 1 μm).

(D) The thickness of adhesive layer on adhesive columns is about 2 μm (Scale bar, 0.5 μm).

(E) The thickness of adhesive layer on adhesive knobs is up to 20 μm (Scale bar, 10 μm).

AN, adhesive network; AC, adhesive column; AK, adhesive knob. See also Figures S2 and S3, and Tables S3 and S4.

The derived phylogenomic tree suggested that the nematode-trapping fungi underwent morphological simplification in trapping devices through evolution. However, the morphological simplification of traps has not weakened the nematode-capturing capacity. On the contrary, one single adhesive knob can immobilize nematodes of different sizes, whereas each constricting ring can only catch nematodes of a specific-size category (Figure 1H). Ultrastructural studies revealed that the adhesive trapping devices captured nematodes by means of an adhesive layer covering the trap surfaces (Belder et al., 1996, Tunlid et al., 1991). Specifically, the adhesion of nematodes to fungal traps as well as the nematode-trapping efficiency significantly decreased when the adhesive layer was denatured (Tunlid et al., 1991).

Ultrastructural Measurements Reveal Increase of Adhesiveness on Trap Surfaces

We measured the thickness of the adhesive layers on trap surfaces of the examined species. We found no adhesive layer on cells of CRs or on un-induced hyphae of all trapping devices (Figure 2B). On the contrary, different adhesive traps produced adhesive layers that differed greatly in their thickness. Specifically, a 0.2- to 0.4-μm-thick layer matrix was observed on the surface of ANs (Figure 2C), and about 1-2 μm for ACs (Figure 2D) and up to 20 μm for AKs (Figure 2E), respectively. Thus, the combined results based on ultrastructural observations and the phylogenomic tree suggested that increasing adhesiveness on trap surfaces was a key innovation allowing NTF to capture nematodes with a high efficiency even with morphologically simple trapping devices.

Comparative Genomic Analyses Reveal Expansion of Genes Encoding Adhesion Proteins

To further investigate the underlying genetic basis for pathogenic adaptation of the nematode-trapping fungi, genomic and comparative genomic analyses were performed. Genomic analysis showed that more than 40% of protein-coding genes belonged to multi-gene families (Table S5). The results revealed that selected groups of genes have significantly expanded in NTF genomes. Specifically, comparative analyses identified that 12 multi-gene families and 23 gene domains have significantly expanded (p < 0.05) in NTF genomes (Figures S1A and S1B). Interestingly, nine of the expanded multi-gene families lack significant matches in public databases, suggesting the existence of potentially novel genetic pathways underlying pathogenesis of NTF. Examples of the expanded gene families include lectins and proteins containing the yeast cell wall-integrity and stress-response component (WSC) domain and the Winged-helix (WH) domain. Lectins have been previously proposed to mediate the interactions between several parasitic fungi (including NTF) and their hosts (Rosen et al., 1996). Proteins containing the WSC domain serve as cell wall sensors (Dupres et al., 2009) and are involved in fungal adhesions (Linder and Gustafsson, 2008). Proteins containing the WH domain play very important roles during DNA binding of transcription factors (Lilley, 1995).

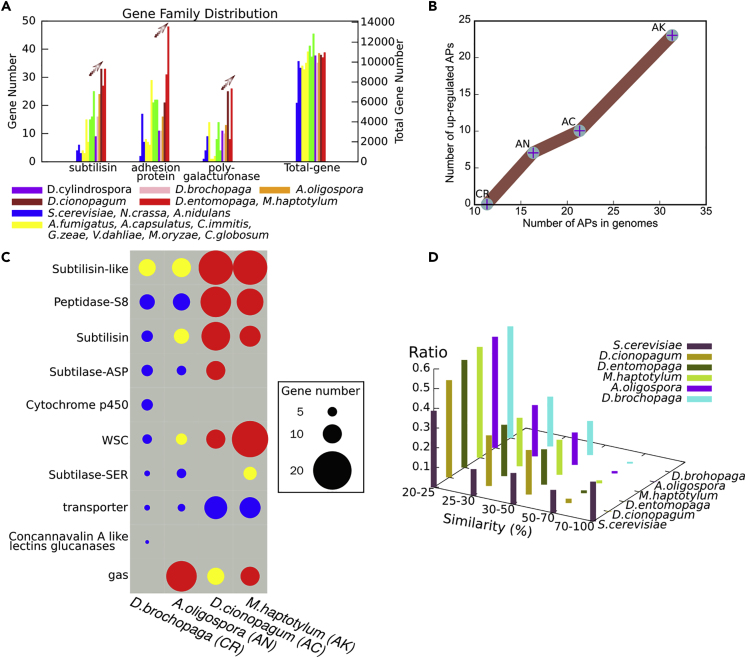

Previous studies have identified a diversity of genes and gene families related to fungal pathogenicity (Meerupati et al., 2013, Yang et al., 2011). Comparative analysis showed that some of them significantly expanded in NTF genomes (Figure S1C). For example, three gene families, including subtilisins, adhesion proteins, and polygalacturonases, showed continuous expansion during the evolution of progressively simplified trapping devices (Figure 3A). Subtilisins are known to play important roles in the pathogenicity of carnivorous fungi (Ahman et al., 2002). The polygalacturonases degrade lectin networks comprising cell walls and play an important role in fungal pathogenicity to plants (D'Ovidio et al., 2004). And, adhesion proteins help fungi adhere to a diversity of surfaces (Ebbole, 2007, Mayer et al., 2013).

Figure 3.

Comparative Genomic Analyses

(A) The gene members showed continuous expansion along the evolutionary history of nematode-trapping fungi.

(B) Real-time PCR analysis showed the number of up-regulated genes encoding adhesion proteins (AP) was consistent with their distributions on genomes, i.e., the numbers increased in the order of CR-AN-AC-AK. There was no adhesion gene up-regulated in D. brochopaga (CR), whereas D. entomopaga (AK) had the most adhesion genes with up-regulated expression.

(C) The species-specific genes of the representative nematode-trapping fungi were found differently enriched in gene expansion. Blue circle represents “not significantly enriched,” yellow circle represents "significantly enriched," and red circle represents "significantly enriched after Bonferroni correction"; circle size represents gene number.

(D) Nematode-trapping fungi (NTF) possess few highly similar genes, whereas the model fungus S. cerevisiae (without RIP) had many highly similar genes.

NTF, nematode-trapping fungi; CR, constricting ring; AN, adhesive network; AC, adhesive column; AK, adhesive knob; AP, adhesion protein. See also Figures S1 and S2, and Tables S2–S6.

Ultrastructural studies showed that the trapping devices acquired a progressively thicker adhesive layer on the surface of trap cells after they evolved the ability to trap nematodes by adhesion. In the NTF genomes, the genes encoding adhesion proteins were significantly expanded and the expansion paralleled the increasing adhesiveness of the trapping devices (Figures 3A and 3B). Specifically, there are 11 adhesion protein-encoding genes in D. brochopaga (CR), 16 in A. oligospora (AN), 21 in D. cionopagum (AC), and 31 in D. entomopaga (AK). There is a positive correlation between the number of adhesion proteins and the thickness of adhesive layer of corresponding trapping devices.

Genes Encoding Adhesion Proteins Show Consistent Up-Regulations

To further investigate the relationship between adhesion proteins and trap induction of NTF, quantitative RT-PCR was performed to measure the gene expression levels of APs during the trap formation when induced by live nematodes. Gene expression analysis showed that the up-regulation of APs during trap induction was also consistent with both expansion of APs in genomes and the increasing adhesiveness of traps. Specifically, 7 genes encoding APs were significantly up-regulated (3 replicates, fold change >2) during induction of ANs and 10 were significantly up-regulated in ACs, whereas 23 were significantly up-regulated during induction of AKs (Figure 3B). In contrast, no APs were found up-regulated during the induction of CRs, which capture the nematodes by means of mechanical forces instead of adhesive layers. The positive correlation also exists between the thickness of adhesive layer and the numbers of up-regulated adhesion proteins during trap induction. Taken together, the nematode-trapping fungi using CRs have the least number of APs encoded in genome, whereas the fungi using AKs have most APs and the thickest adhesive layer on trap surface.

Our previous work showed that disruption of adhesion-related gene reduced the production of adhesive layer on trap surface of A. oligospora and significantly decreased its ability to capture nematodes (Liang et al., 2015). The results suggest that the significant expansion of APs along the NTF lineage is likely responsible for the gradual thickening of the adhesive layers. Given that capturing the nematodes with various traps is the most crucial step of infection by NTF, the number of APs and their regulation represent a key factor in shaping the evolution of various traps and achieving corresponding adaptation.

Species-Specific Genes Emerged in Different Genomes

Comparative analysis has also identified large numbers of species-specific genes among NTF genomes (Figure 2A). Interestingly, the species-specific genes were found enriched in many of the expanded pathogenicity-related gene families (Figure S2). Compared with the non-species-specific genes that are shared with non-NTF species, the species-specific genes possessed a few marked features. For example, the average length of proteins encoded by species-specific genes was 332 amino acids, much shorter than that of non-species-specific genes (509 amino acids). Second, a large proportion (72%) of the species-specific genes had no homologous matches in public databases. Third, there were fewer paralogs in species-specific genes than in other genes. Specifically, in non-species-specific genes, an average of 47% of the protein-encoding genes belonged to multi-gene families (Table S5), whereas in species-specific genes, the average number was 19%. Indeed, less than 3% of species-specific genes belonged to 12 large clusters consisting of more than 10 paralogs. The results on species-specific genes suggest that their expansions are likely related to gene diversification that contributes significantly to functional innovation of the nematode-trapping fungi.

Enrichment analysis showed that the species-specific genes among the NTF differed in gene expansion patterns. For example, all the species-specific genes of NTF are enriched in genes encoding subtilisin-like proteins, but D. brochopaga has much fewer coding genes than those developing adhesive trapping devices (Figure 3C). D. cionopagum, D. entomopaga, and M. haptotylum with morphologically simple adhesive traps are enriched in genes encoding subtilisins and peptidases, suggesting important roles of proteolysis in their infectious attack. In A. oligospora, the genes coding for GAS proteins are highly enriched. GAS proteins bind to the plasma membrane through a lipid anchor and are involved in cell wall synthesis and cell signaling (van Zanten et al., 2009, Verghese et al., 2006). In particular, M. haptotylum contains 19 genes with WSC domains, which is consistent with trap adhesion being very important for adhesive knobs.

Repeat-Induced Point Mutations Involved in Gene Expansion

Gene-family expansion can be caused by gene duplication and is recognized as one of the main mechanisms of adaptive innovation (Gladieux et al., 2014). However, the underlying mechanism for gene duplication and diversity is often unknown. Genomic analyses revealed that less than 2% of NTF genomes consisted of repetitive sequences (Table S2), even lower than that in the model filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa (Galagan et al., 2003, Selker, 1990) in which the repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) has been considered as responsible for its low percentage of repetitive sequences. RIP is a homology-based process that mutates repetitive sequences. Thus, RIP can significantly impact genome evolution by slowing the creation of new genes through genomic duplication (Galagan and Selker, 2004). Here, we calculated RIP indices to determine whether RIP contributed to the evolution of NTF genomes. By using the default settings (Hane and Oliver, 2008), positive RIP responses were detected in various genomic regions (Table S6), including multi-gene families and repetitive sequences. In addition, consistent with the actions that RIP mutates duplicated sequences with greater than about 80% nucleotide similarity (Galagan et al., 2003), there are very few highly similar genes within the sequenced NTF genomes (Figure 3D). In particular, homologous genes with more than 70% similarity are almost absent from NTF genomes, whereas there are many such genes in S. cerevisiae. In addition, the RIP process requires the RID1 gene (Freitag et al., 2002). The homologous gene of RID1 has been found in all the NTF genomes. Furthermore, DNA methylation is usually associated with RIP (Singer et al., 1995). We performed a DNA methylation analysis of the whole genome of A. oligospora and identified a total of 737 5-mC positions, and positive RIP responses were detected in 705 of them. The results suggest that the RIP mechanism has had a profound impact on gene expansion in nematode-trapping fungi and contributes significantly to their pathogenic adaptation.

Discussion

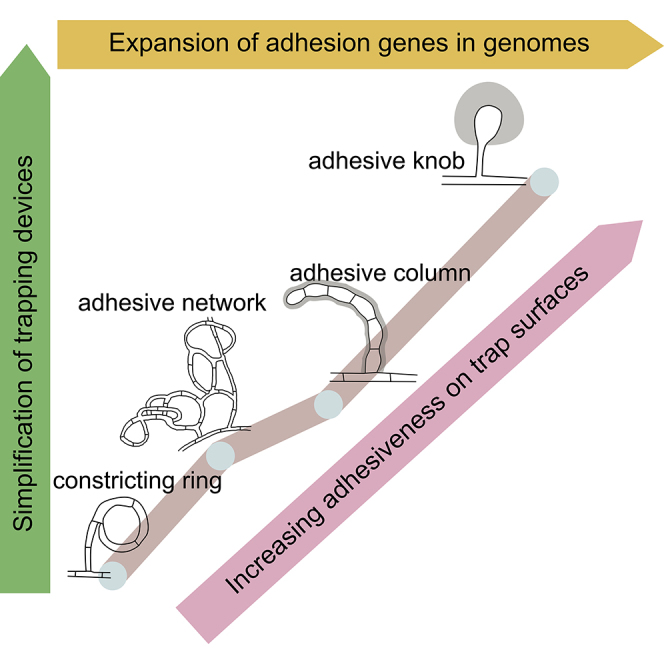

Lifestyle transition is a fundamental property of fungi in their responses to environmental changes. For nematode-trapping fungi, nitrogen deficiency is a common inducer for developing traps to capture nematodes (Nordbring-Hertz et al., 2006). Through evolution, various trapping devices likely emerged to deal with nitrogen deficiency. As the earliest emerged and morphologically the most complicated trapping device, CRs immobilize nematodes actively and mechanically by rapid swelling of three highly ordered ring cells. However, large nematodes cannot enter CRs and small nematodes can pass through the traps without triggering any response (Figure 1J). In contrast, the passive adhesive traps capture nematodes by means of adhesive layers on the surfaces of trap cells and can capture nematodes using a single adhesive knob (Figure 1H). Therefore, the simplification of traps has not reduced trapping efficiency but instead has likely provided competitive advantages. However, the simplification of trapping structures may have caused a reduction in the contact area between the fungi and nematodes, thus increasing the requirement for surface adhesiveness. The observed continuous expansion of adhesion proteins and the consequent thickening of adhesive layers are consistent with the above hypothesis to ensure capture efficiency with even simple trap structures (Figure 4). In addition, the continuous expansion of subtilisins and other related genes could enhance the ability of the fungi to penetrate and digest the nematodes after the nematodes are captured.

Figure 4.

A Proposed Model for Trap Evolution and Carnivorous Adaptation of the Nematode-Trapping Fungi

Gene duplication and divergence provide basis for genomic evolution, which leads to progressive thickening of adhesive layers on trap surface. The increasing adhesiveness is coupled with changes in the nematode-capturing mechanism from mechanic force to adhesive traps, followed by simplification of adhesive trapping devices while ensuring capturing efficiency. The adhesive layer is shown in gray. CR, constricting ring; AN, adhesive network; AC, adhesive column; AK, adhesive knob. See also Figure S4.

Gene duplication and divergence are important mechanisms for adaptive innovation (Gladieux et al., 2014, Hittinger and Carroll, 2007). Among NTF genomes, 44% of protein-coding genes belong to multi-gene families. Our analyses showed that trap evolution was associated with significant expansion of multiple gene families and many of them may function in pathogenicity of the nematode-trapping fungi. RIP plays important roles in gene duplication. Positive RIP responses have been detected in repetitive sequences, multi-gene families, species-specific genes, and DNA methylation positions in NTF genomes. In S. cerevisiae, more than 30% of gene pairs have more than 50% sequence identities, whereas in nematode-trapping fungi, the highly similar genes are almost completely absent (Figure 3D). Genomic rearrangement can also result in gene duplication. Syntenic analyses can be used for identification of genomic rearrangement. An example of genomic inversion among the sequenced NTF is shown in Figure S4. Genomic rearrangement could also facilitate the emergence of species-specific genes. Indeed, some of the species-specific genes are highly enriched in certain genomic regions. The low sequence similarity in gene families, large numbers of species-specific genes and few paralogs in species-specific genes suggest functional diversification following gene duplication. Other than the nematode-trapping fungi, other fungal pathogens (Table S5) also showed patterns of gene expansion and accumulation of species-specific genes. For example, search against PHI (pathogen-host interaction) gene database (Winnenburg et al., 2008) identified that the nematode-trapping fungi share more putative PHI genes with fungal pathogens (including animal and plant pathogens, Table S4) than with saprophytes (101 versus 19). Interestingly, they share more putative PHI genes with plant fungal pathogens (including M. oryzae) than with animal fungal pathogens (37 versus 23). The result is consistent with previous observations showing the putative PHI genes being enriched in plant-pathogen interaction and the important roles of poly-galacturonases in fungal pathogenicity to plants.

For most fungal pathogens, attachment to host tissues is among the most crucial stage for successful infection. These attachments are generally mediated by cell surface adhesion molecules (Aw and Hue, 2017, Ebbole, 2007, Mayer et al., 2013). These molecules play critical roles in the establishment of fungal infections of plants, animals, and humans. In this study, we demonstrated that expansion of genes encoding adhesion proteins in nematode-trapping fungi was positively correlated with the thickening of adhesive layers on the surface of trapping devices during lifestyle transitions, which ensure high efficiency for capturing nematode preys using simplified trapping devices (Figure 4). Expansion of adhesion proteins is thus a key driver in the evolution of nematode-trapping fungi and their trapping devices. Our results suggest that adhesion proteins play critical roles in the adaptive evolution and pathogenesis of nematode-trapping fungi. However, lifestyle transitions of nematode-trapping fungi involve multiple complex stages and adhesion is just the beginning of fungal predation on nematodes. The genomic resources generated here should help further studies on the genetic bases and molecular mechanisms underlying lifestyle transitions and pathogenesis of nematode-trapping fungi.

Limitations of the Study

Our analyses indicated a likely process for the evolution of nematode trapping devices and suggested the possible mechanisms underlying trapping device simplification while enhancing nematode trapping efficiencies. However, given the prevalence of RIP, how exactly the gene family expansion escaped RIP during evolution remains unknown. Similarly, previous studies have shown that disruption of adhesion-related gene reduced the adhesive layers of trap surface of A. oligospora, and how the adhesion genes interact to control the thickness of the adhesive layers among various NTF requires further investigation. In our investigations, we also identified the expansion of several other gene families such as subtilisins and polygalacturonases involved in the degradations of proteins and other macromolecules. Their roles in trapping device evolution and NTF adaptation, including how they interact with adhesion proteins to ensure capturing capacity, remain to be investigated.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

We thank BGI-Shenzhen who contributed to the genome projects. We acknowledge grant support from the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program: 2013CB127500), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31270131, 31160021, and U1502262), the Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications Scientific Foundation (NUPTSF) (NY218140), and a grant (2018KF003) from YNCUB.

Author Contributions

K.-Q.Z. and X.J. conceived the study and designed scientific objectives. K.-Q.Z. led the project. X.J. analyzed the data and prepared the manuscript. Z.Y. provided the materials and performed the experiments. J.Y. contributed to experiments. J.X. contributed to manuscript preparation. Y.Z., S.L., C.Z., J.L., and L.L. participated in discussions and provided suggestions.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: May 22, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101057.

Data and Code Availability

All the data and methods necessary to reproduce this study are included in the manuscript and Supplemental Information. The genome projects have been deposited at GenBank under the BioProject accession number PRJNA283584, PRJNA283942, PRJNA283944, and PRJNA283946. The gene annotation information has been included.

Supplemental Information

References

- Abad P., Gouzy J., Aury J.M., Castagnone-Sereno P., Danchin E.G., Deleury E., Perfus-Barbeoch L., Anthouard V., Artiguenave F., Blok V.C. Genome sequence of the metazoan plant-parasitic nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:909–915. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahman J., Johansson T., Olsson M., Punt P.J., van den Hondel C.A., Tunlid A. Improving the pathogenicity of a nematode-trapping fungus by genetic engineering of a subtilisin with nematotoxic activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:3408–3415. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.7.3408-3415.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aw K.M.S., Hue S.M. Mode of infection of Metarhizium spp. fungus and their potential as biological control agents. J. Fungi (Basel) 2017;3:30. doi: 10.3390/jof3020030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belder E.d., Jansen E., Donkers J. Adhesive hyphae of Arthrobotrys oligospora: an ultrastructural study. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 1996;102:471–478. [Google Scholar]

- Cracraft J., Donoghue M.J. Oxford University Press; 2004. Assembling the Tree of Life. [Google Scholar]

- D'Ovidio R., Mattei B., Roberti S., Bellincampi D. Polygalacturonases, polygalacturonase-inhibiting proteins and pectic oligomers in plant-pathogen interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1696:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupres V., Alsteens D., Wilk S., Hansen B., Heinisch J.J., Dufrene Y.F. The yeast Wsc1 cell surface sensor behaves like a nanospring in vivo. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:857–862. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbole D.J. Magnaporthe as a model for understanding host-pathogen interactions. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2007;45:437–456. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.45.062806.094346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M.C., Henk D.A., Briggs C.J., Brownstein J.S., Madoff L.C., McCraw S.L., Gurr S.J. Emerging fungal threats to animal, plant and ecosystem health. Nature. 2012;484:186–194. doi: 10.1038/nature10947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag M., Williams R.L., Kothe G.O., Selker E.U. A cytosine methyltransferase homologue is essential for repeat-induced point mutation in Neurospora crassa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002;99:8802–8807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132212899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galagan J.E., Selker E.U. RIP: the evolutionary cost of genome defense. Trends Genet. 2004;20:417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galagan J.E., Calvo S.E., Borkovich K.A., Selker E.U., Read N.D., Jaffe D., FitzHugh W., Ma L.J., Smirnov S., Purcell S. The genome sequence of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Nature. 2003;422:859–868. doi: 10.1038/nature01554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier G.M. Dimorphism in fungal pathogens of mammals, plants, and insects. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004608. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladieux P., Ropars J., Badouin H., Branca A., Aguileta G., de Vienne D.M., Rodriguez de la Vega R.C., Branco S., Giraud T. Fungal evolutionary genomics provides insight into the mechanisms of adaptive divergence in eukaryotes. Mol. Ecol. 2014;23:753–773. doi: 10.1111/mec.12631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hane J.K., Oliver R.P. RIPCAL: a tool for alignment-based analysis of repeat-induced point mutations in fungal genomic sequences. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:478. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hittinger C.T., Carroll S.B. Gene duplication and the adaptive evolution of a classic genetic switch. Nature. 2007;449:677–681. doi: 10.1038/nature06151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X., Li H., Zhang W., Wang J., Liang L., Zou C., Yu Z., Liu S., Zhang K.Q. The lifestyle transition of Arthrobotrys oligospora is mediated by microRNA-like RNAs. Sci. China Life Sci. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s11427-018-9437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer A.M., Teitelbaum C.S., Griffin A., Drake J.M. Multiscale model of regional population decline in little brown bats due to white-nose syndrome. Ecol. Evol. 2019;9:8639–8651. doi: 10.1002/ece3.5405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang L., Shen R., Mo Y., Yang J., Ji X., Zhang K.Q. A proposed adhesin AoMad1 helps nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora recognizing host signals for life-style switching. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2015;81:172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilley D.M.J. IRL Press at Oxford University Press; 1995. DNA-protein: Structural Interactions. [Google Scholar]

- Linder T., Gustafsson C.M. Molecular phylogenetics of ascomycotal adhesins--a novel family of putative cell-surface adhesive proteins in fission yeasts. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2008;45:485–497. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer F.L., Wilson D., Hube B. Candida albicans pathogenicity mechanisms. Virulence. 2013;4:119–128. doi: 10.4161/viru.22913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerupati T., Andersson K.M., Friman E., Kumar D., Tunlid A., Ahren D. Genomic mechanisms accounting for the adaptation to parasitism in nematode-trapping fungi. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003909. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu X.M., Zhang K.-Q. Arthrobotrys oligospora: a model organism for understanding the interaction between fungi and nematodes. Mycology. 2011;2:59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Nordbring-Hertz B., Jansson H.B., Tunlid A. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2006. Nematophagous Fungi. [Google Scholar]

- O'Hanlon S.J., Rieux A., Farrer R.A., Rosa G.M., Waldman B., Bataille A., Kosch T.A., Murray K.A., Brankovics B., Fumagalli M. Recent Asian origin of chytrid fungi causing global amphibian declines. Science. 2018;360:621. doi: 10.1126/science.aar1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto M., Wedin M. Dating the diversification of the major lineages of Ascomycota (Fungi) PLoS One. 2013;8:e65576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen S., Kata M., Persson Y., Lipniunas P.H., Wikstrom M., Van Den Hondel M.J., Van Den Brink J., Rask L., Heden L.O., Tunlid A. Molecular characterization of a saline-soluble lectin from a parasitic fungus. Extensive sequence similarities between fungal lectins. Eur. J. Biochem. 1996;238:822–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0822w.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selker E.U. Premeiotic instability of repeated sequences in Neurospora crassa. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1990;24:579–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.24.120190.003051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M.J., Marcotte B.A., Selker E.U. DNA methylation associated with repeat-induced point mutation in Neurospora crassa. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995;15:5586–5597. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipiczki M. Where does fission yeast sit on the tree of life? Genome Biol. 2000;1 doi: 10.1186/gb-2000-1-2-reviews1011. reviews1011.1–1011.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunlid A., Johansson T., Nordbring-Hertz B. Surface polymers of the nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1991;137:1231–1240. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-6-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese G.M., Gutknecht M.F., Caughey G.H. Prostasin regulates epithelial monolayer function: cell-specific Gpld1-mediated secretion and functional role for GPI anchor. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C1258–C1270. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00637.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winnenburg R., Urban M., Beacham A., Baldwin T.K., Holland S., Lindeberg M., Hansen H., Rawlings C., Hammond-Kosack K.E., Kohler J. PHI-base update: additions to the pathogen host interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D572–D576. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Yang E., An Z., Liu X. Evolution of nematode-trapping cells of predatory fungi of the Orbiliaceae based on evidence from rRNA-encoding DNA and multiprotein sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2007;104:8379–8384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702770104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Wang L., Ji X., Feng Y., Li X., Zou C., Xu J., Ren Y., Mi Q., Wu J. Genomic and proteomic analyses of the fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora provide insights into nematode-trap formation. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002179. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang E., Xu L., Yang Y., Zhang X., Xiang M., Wang C., An Z., Liu X. Origin and evolution of carnivorism in the Ascomycota (fungi) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2012;109:10960–10965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120915109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zanten T.S., Cambi A., Koopman M., Joosten B., Figdor C.G., Garcia-Parajo M.F. Hotspots of GPI-anchored proteins and integrin nanoclusters function as nucleation sites for cell adhesion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:18557–18562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905217106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K.Q., Hyde K.D. Vol 23. Springer; 2014. (Nematode-Trapping Fungi). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data and methods necessary to reproduce this study are included in the manuscript and Supplemental Information. The genome projects have been deposited at GenBank under the BioProject accession number PRJNA283584, PRJNA283942, PRJNA283944, and PRJNA283946. The gene annotation information has been included.