Abstract

Background

Aspirin has not been reliably shown to reduce all-cause and cardiovascular mortality but can prevent symptomatic myocardial infarction. However, silent myocardial infarction (SMI) is not uncommon in clinical practice. No meta-analysis has compared the effect of aspirin administration on primary prevention of all myocardial infarctions, including SMI.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Library and Google Scholar for randomized double-blind controlled trials evaluating the effect of aspirin on primary prevention of all myocardial infarctions, including SMI.

Results

The current meta-analysis included 9 trials involving 67,486 patients and 67,557 controls on aspirin primary prevention of all myocardial infarctions. When SMI was included in the total number of myocardial infarctions, the aspirin effect on the primary prevention of myocardial infarction was not as significant as expected [risk ratio (RR): 0.883; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.780 to 1.001; P=0.052].

Conclusions

Aspirin may not provide a primary preventive effect in all myocardial infarction patients. Previously demonstrated reductions in myocardial infarction are not present when SMI is included.

Keywords: Aspirin, primary prevention, myocardial infarction

Introduction

The primary preventive effect of aspirin on cardiovascular events has been a controversial issue in past decades. Early studies conducted before 2000 (1,2) consistently considered aspirin to confer a greater benefit than risk in primary prevention. As a result, aspirin was recommended for people with increased cardiovascular risk to balance the benefit-risk ratio. However, studies since 2000 (3,4) have shown little or no benefit from aspirin. In particular, three large studies [Aspirin to Reduce Risk of Initial Vascular Events (ARRIVE) (5), Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) (6), and A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes (ASCEND) (7)] published in 2018 suggested that aspirin might increase bleeding risks and was far from providing significant benefits in primary prevention.

The latest meta-analysis (8) included clinical trials comparing aspirin versus placebo (or no aspirin) for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a minimum follow-up duration of 1 year. The results showed that aspirin reduced the risk of nonfatal myocardial infarction but significantly increased the risk of nonfatal bleeding compared with that in controls. However, the meta-analysis focused only on the primary prevention of symptomatic myocardial infarction with aspirin but paid little attention to silent (or asymptomatic) myocardial infarction (SMI), which actually has an incidence as high as 35% in high-risk populations (9). Thus, the current meta-analysis was performed to determine the association between aspirin and all myocardial infarctions, including SMI.

Methods

Literature search

Studies on aspirin for the primary prevention of all myocardial infarctions were searched in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Library and Google Scholar. Included studies had to be randomized double-blind controlled trials and provide sufficient primary data (including patient number and events of myocardial infarction in the aspirin group and control group). The language was limited to English, and the search was finished on July 27, 2019.

The search strategy was as follows: (‘aspirin’ OR ‘acetylsalicylic acid’ OR ‘acetylsalicylate’ OR ‘2-acetoxybenzoic acid’) AND (‘myocardial infarction’ OR ‘acute myocardial infarction’ OR ‘silent myocardial infarction’ OR ‘asymptomatic myocardial infarction’ OR ‘acute coronary syndrome’ OR ‘heart attack’ OR ‘MI’ OR ‘AMI’ OR ‘SMI’ OR ‘ACS’) AND (‘primary prevention’ OR ‘primary care’ OR ‘healthy population’ OR ‘general population’).

Reference lists of all included studies were also carefully read for potential studies. Dr. Yi Luan and Dr. Ya Li independently evaluated articles. If there was any disagreement on inclusion, it was resolved by discussion with another author, Dr. Wenbin Zhang.

Data extraction

Information including trial name, year of publication, country of population, sample size, subject characteristics, follow-up year, and aspirin dosage were extracted from each study.

Quality assessment

The quality of all original studies was evaluated in accordance with the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool, including selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias and reporting bias. The absence of the above five biases was considered indicative of high quality.

Statistical analysis

The effects of aspirin on the primary prevention of myocardial infarction were estimated by calculating the pooled risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). The Z-test was used to determine the significance of pooled RR. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

I2 was used to evaluate the heterogeneity of the included studies. When I2>50%, the effects were assumed to be homogeneous, and the random-effects model was used. When I2≤50%, the fixed-effects model was applied. Publication bias was assessed using standard normal deviate (SND) linear regression and Egger’s linear regression tests.

All data analyses were performed using STATA 11.0 software (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

After initial screening, fifteen full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. However, the British Male Doctors (BMD) (10), Primary Prevention Project (PPP) (11), Japanese Primary Prevention Project (JPPP) (12), Japanese Primary Prevention of Atherosclerosis With Aspirin for Diabetes (JPAD) (13) and Aspirin for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Renal Disease Progression in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients (AASER) (14) studies had high performance bias because they were not blind. The 650 mg/day aspirin dosage in the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) (15) was much higher than the current dosage used for prevention. We ultimately included 9 original studies (1-7,16,17) with 135,043 participants (aspirin group n=67,486, vs. control group n=67,557). The characteristics of the included trials are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of included trials of aspirin for primary cardiovascular prevention.

| Study, year | Country | Study design | Randomly, N | Dose | Inclusion | Male% | Follow-up, years | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHS, 1989 (2) | United States | 2×2 RCT, beta carotene | 22,071 | 325 mg alternate day | Male physicians aged 40–84 y | 100 | 5.0 | High |

| HOT, 1998 (1) | 26 countries | 3×2 RCT, felodipine + other agents to achieve target blood pressure | 18,790 | 75 mg/d | Aged 50–80 y with hypertension | 53 | 3.8 | High |

| TPT, 1998 (17) | United Kingdom | 2×2 RCT, warfarin | 2,540 | 75 mg/d | Men with high IHD risk aged 45–69 y | 100 | 6.8 | High |

| WHS, 2005 (16) | United States | 2×2 RCT, vitamin E | 39,876 | 100 mg alternate day | Healthy women 45 y of age or older | 0 | 10.1 | High |

| POPADAD, 2008 (4) | Scotland | 2×2 RCT, antioxidant capsule | 1,276 | 100 mg/d | Aged 40 y or more with DM and ABI ≤0.99 | 44.1 | 6.7 | High |

| AAA, 2010 (3) | Scotland | RCT | 3,350 | 100 mg/d | ABI ≤0.95 aged 50–75 y | 28.5 | 8.2 | High |

| ASPREE, 2018 (6) | Australia and United States | RCT | 19,114 | 100 mg/d | 70 years of age or older (or ≥65 years of age among blacks and Hispanics in the United States) | 43.6 | 4.7 | High |

| ASCEND, 2018 (7) | United Kingdom | RCT | 15,480 | 100 mg/d | DM at least 40 y of age | 62.6 | 7.4 | High |

| ARRIVE, 2018 (5) | 7 countries | RCT | 12,546 | 100 mg/d | Aged ≥55 y (male) or 60 y (female) with an average cardiovascular risk | 70.4 | 5.0 | High |

PHS, Physicians’ Health Study; HOT, Hypertension Optimal Treatment; TPT, Thrombosis prevention Trial; WHS, Women’s Health Study; POPADAD, Prevention Of Progression of Arterial Disease And Diabetes; AAA, Aspirin for Asymptomatic Atherosclerosis; ASPREE, Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly; ASCEND, A Study of Cardiovascular Events In Diabetes; ARRIVE, Aspirin to Reduce Risk of Initial Vascular Events; RCT, randomized controlled trial; IHD, ischemic heart disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; ABI, ankle brachial index.

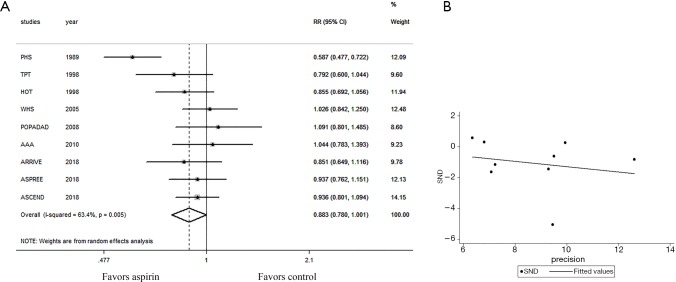

Similar to the results of the latest meta-analysis, aspirin reduced the risk of myocardial infarction (RR: 0.860; 95% CI: 0.747 to 0.991; P=0.037 for test of effect; I2=69.6%, P<0.1 for homogeneity). However, when SMI was included, aspirin showed only a trend in reducing the risk of myocardial infarction, with no statistically significant difference (RR: 0.883; 95% CI: 0.780 to 1.001; P=0.052 for test of effect; I2=63.4%, P<0.1 for homogeneity, Figure 1A), suggesting that aspirin may not be suitable for primary prevention of all myocardial infarctions. To identify potential sources of heterogeneity, we removed Physicians’ Health Study (PHS) (2) from the meta-analysis, as it was terminated ahead of schedule, and its participants were male physicians who had high educational and economic status and who received a higher dosage of aspirin. We found that the effect of aspirin on primary prevention of all myocardial infarctions was further attenuated (RR: 0.935; 95% CI: 0.864 to 1.011; P=0.092 for test of effect; I2=0.0%, P=0.671 for homogeneity). No publication bias was observed with SND linear regression (Figure 1B) or Egger’s test (P=0.881).

Figure 1.

Primary prevention of all myocardial infarctions with aspirin vs. control. (A) Forest plot: individual and pooled RRs with 95% CIs and the weight of the corresponding study in the meta-analysis. (B) SND scatter plot: SND on the vertical axis is equal to the logarithm of RR over its standard error, and the precision on the horizontal axis is the reciprocal of the standard error. The extension line of the regression line passes through the origin (P=0.881), indicating no publication bias. RR, risk ratio; CI, confidence interval; SND, standard normal deviate.

Discussion

Our analysis revealed that the aspirin effect on the primary prevention of myocardial infarction was not as significant as expected when SMI was included in the total number of myocardial infarctions. SMI is one type of myocardial infarction. Like symptomatic myocardial infarction, it can occur at rest or in an active state. It is characterized by atypical clinical symptoms or no symptoms and a lack of clear objective signs of myocardial infarction, but evidence of myocardial necrosis can be found by the relevant tests. Currently, myocardial infarction with typical symptoms is commonly diagnosed in clinical practice, while SMI is rarely clinically recognized. Nevertheless, recent studies have confirmed that SMI is a clinical syndrome occurring throughout the course of coronary artery disease and does not occur by chance. The lesions may have existed for months or even years, and this type of patient is actually not rare but only clinically difficult to identify. It has been reported that SMI accounts for up to approximately half of the total number of myocardial infarctions in different studies (9,18-21), indicating that SMI is a very common phenomenon.

At the same time, patients with SMI belong to a high-risk subgroup. They are often unaware of their illness and do not limit their activities. With SMI, the incidence of heart failure was significantly increased (20,22), and the effects of high-risk factors, such as smoking, reduced physical activity, high body mass index, poor dietary habits, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and hyperglycaemia, on cardiovascular disease were almost doubled (23). If clinically manifested acute myocardial infarction patients were found to have prior SMI by late gadolinium enhancement cardiac magnetic resonance (LGE-CMR) images, they would have a more than 3-fold risk of mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events (21). Furthermore, 42.4% of the individuals who experienced sudden cardiac death without a clinical history of coronary artery disease were detected to have a previous SMI at autopsy (24). All these findings indicate that the presence of SMI is an important prognostic indicator, and SMI patients require attention. Our study found that the preventive effect of aspirin on total myocardial infarction was weakened after the inclusion of SMI, suggesting that aspirin may not exert an overall primary preventive effect on all myocardial infarctions patients. However, due to the heterogeneity of the study population and the limitations of SMI detection methods (electrocardiography used in previous studies might miss smaller infarctions, and not all patients produce Q waves after infarction), it is still challenging to demonstrate that aspirin is completely useless. Though screening SMI by electrocardiography is cost-effective, the sensitivity and negative predictive value of electrocardiography are lower than those of CMR (25). Accordingly, further studies are needed to determine, for example, the location and distribution of scar tissues using LGE-CMR to validate and evaluate the presence and extent of SMI.

Conclusions

Previously demonstrated reductions in myocardial infarction are not present with aspirin primary prevention when SMI is included. Aspirin may not provide a primary preventive effect in all myocardial infarction patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81700213) and the Medical and Health Technology Program of Zhejiang Province (2018263306).

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Luan has been given complimentary Fellow-in-Training membership in the American College of Cardiology. Dr. Fu has been elected as a Fellow of the American College of Cardiology. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet 1998;351:1755-62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04311-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steering Committee of the Physicians' Health Study Research Group . Final report on the aspirin component of the ongoing Physicians' Health Study. N Engl J Med 1989;321:129-35. 10.1056/NEJM198907203210301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fowkes FG, Price JF, Stewart MC, et al. Aspirin for prevention of cardiovascular events in a general population screened for a low ankle brachial index: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;303:841-8. 10.1001/jama.2010.221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belch J, MacCuish A, Campbell I, et al. The prevention of progression of arterial disease and diabetes (POPADAD) trial: factorial randomised placebo controlled trial of aspirin and antioxidants in patients with diabetes and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease. BMJ 2008;337:a1840. 10.1136/bmj.a1840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaziano JM, Brotons C, Coppolecchia R, et al. Use of aspirin to reduce risk of initial vascular events in patients at moderate risk of cardiovascular disease (ARRIVE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2018;392:1036-46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31924-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNeil JJ, Wolfe R, Woods RL, et al. Effect of Aspirin on Cardiovascular Events and Bleeding in the Healthy Elderly. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1509-18. 10.1056/NEJMoa1805819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Ascend Study Collaborative Group , Bowman L, Mafham M, et al. Effects of Aspirin for Primary Prevention in Persons with Diabetes Mellitus. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1529-39. 10.1056/NEJMoa1804988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdelaziz HK, Saad M, Pothineni NVK, et al. Aspirin for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Events. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:2915-29. 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pride YB, Piccirillo BJ, Gibson CM. Prevalence, consequences, and implications for clinical trials of unrecognized myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2013;111:914-8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.11.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peto R, Gray R, Collins R, et al. Randomised trial of prophylactic daily aspirin in British male doctors. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988;296:313-6. 10.1136/bmj.296.6618.313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Gaetano G, Collaborative Group of the Primary Prevention Project . Low-dose aspirin and vitamin E in people at cardiovascular risk: a randomised trial in general practice. Collaborative Group of the Primary Prevention Project. Lancet 2001;357:89-95. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03539-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikeda Y, Shimada K, Teramoto T, et al. Low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in Japanese patients 60 years or older with atherosclerotic risk factors: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:2510-20. 10.1001/jama.2014.15690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogawa H, Nakayama M, Morimoto T, et al. Low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of atherosclerotic events in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008;300:2134-41. 10.1001/jama.2008.623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goicoechea M, de Vinuesa SG, Quiroga B, et al. Aspirin for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Renal Disease Progression in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients: a Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial (AASER Study). Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2018;32:255-63. 10.1007/s10557-018-6802-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ETDRS Investigators . Aspirin effects on mortality and morbidity in patients with diabetes mellitus. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study report 14. ETDRS Investigators. JAMA 1992;268:1292-300. 10.1001/jama.1992.03490100090033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ridker PM, Cook NR, Lee IM, et al. A randomized trial of low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1293-304. 10.1056/NEJMoa050613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Medical Research Council's General Practice Research Framework . Thrombosis prevention trial: randomised trial of low-intensity oral anticoagulation with warfarin and low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of ischaemic heart disease in men at increased risk. Lancet 1998;351:233-41. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11475-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang ZM, Rautaharju PM, Prineas RJ, et al. Electrocardiographic QRS-T angle and the risk of incident silent myocardial infarction in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. J Electrocardiol 2017;50:661-6. 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2017.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soejima H, Ogawa H, Morimoto T, et al. One quarter of total myocardial infarctions are silent manifestation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Cardiol 2019;73:33-7. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2018.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qureshi WT, Zhang ZM, Chang PP, et al. Silent Myocardial Infarction and Long-Term Risk of Heart Failure: The ARIC Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:1-8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amier RP, Smulders MW, van der Flier WM, et al. Long-Term Prognostic Implications of Previous Silent Myocardial Infarction in Patients Presenting With Acute Myocardial Infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;11:1773-81. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soliman EZ. Silent myocardial infarction and risk of heart failure: Current evidence and gaps in knowledge. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2019;29:239-44. 10.1016/j.tcm.2018.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmad MI, Chevli PA, Barot H, et al. Interrelationships Between American Heart Association's Life's Simple 7, ECG Silent Myocardial Infarction, and Cardiovascular Mortality. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e011648. 10.1161/JAHA.118.011648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vähätalo JH, Huikuri HV, Holmström LTA, et al. Association of Silent Myocardial Infarction and Sudden Cardiac Death. JAMA Cardiol 2019. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.2210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paul TK, Mukherjee D. Silent myocardial infarction and risk of heart failure. Ann Transl Med 2018;6:S35. 10.21037/atm.2018.09.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]