Abstract

This study uses an atomizer and fluorescent markers to simulate contamination of uncovered skin and hair of health care workers wearing personal protective equipment after intubating patient manikins under emergency conditions.

A major challenge with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic is the effective protection of health care workers.1 Recommendations for the use of personal protective equipment to protect against SARS-CoV-2 exposure by health care workers were recently published by the World Health Organization and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. For aerosol-generating procedures, N95 respirators, eye protection, isolation gowns, and gloves were recommended. Coveralls, boots with a cover, and hair coverings were not part of the recommended protective clothing.2,3

We assessed the protection of emergency physicians and nurses wearing the recommended personal protective equipment while caring for a simulated patient with respiratory distress.

Methods

A simulation study was conducted in the emergency department of Rambam Health Care Campus in Haifa, Israel, on March 21, 2020, examining the presence of a surrogate measure of contamination on exposed skin of participants wearing personal protective equipment to protect against SARS-CoV-2 exposure.4 Two scenarios of patients with respiratory distress requiring airway management similar to those commonly encountered in the emergency department were conducted using adult and child high-fidelity manikins (SimMan and SimJunior, Laerdal). An atomizing device (MAD Nasal, Teleflex) was used to simulate droplets exhaled during coughing episodes.5

The adult scenario consisted of a 74-year-old man experiencing fever and shortness of breath with a decline in oxygen saturation level prompting endotracheal intubation and peripheral intravenous cannulation. The simulation lasted 20 minutes. The simulated patient had 2 coughing episodes during which droplets were expelled from the manikin’s nostrils.5 Participating health care workers were instructed to provide airway management and ventilatory support meeting the standard of care for patients with the novel coronavirus disease 2019.6

The intubation was performed by the most skilled physician present using a rapid-sequence intubation technique and was assisted by a second physician. Because bag-mask ventilation prior to intubation could generate aerosols, participants were allowed to use it only when preoxygenation was ineffective. One nurse was responsible for intravenous access and medication administration and a second nurse recorded and assisted with all procedures.

The pediatric scenario was similar. Before the simulation, a nonvisible fluorescent compound (Glo Germ) as a marker of contamination was applied on predetermined surface areas (around the nose and mouth, palms, and upper chest) of the manikin and was added to the simulated secretion areas. After completion of the simulation and before doffing, the fluorescent markers on the participants were visualized and photographed under UV light. The simulations were videotaped to capture all physical contacts between each participant and the manikin to assess possible infection risk.

The ethics committee of Rambam Health Care Campus waived the need for approval and consent because the study was considered a quality control project.

Results

For each simulation (adult and child manikins), 2 physicians and 2 nurses participated (8 total participants). All participants were experienced in emergency department care and had participated in resuscitations.

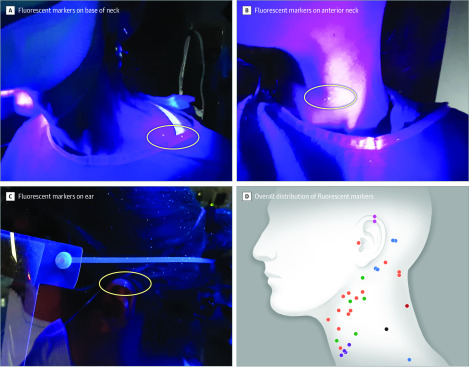

In the adult scenario, intubation was successful during the second videolaryngoscopic attempt. In the pediatric scenario, intubation was successful using direct laryngoscopy after 1 failed videolaryngoscopic attempt. Seven of 8 participants had fluorescent markers on their exposed skin, 6 on the neck and 1 on an ear (Figure).

Figure. UV Visualization of Contaminated Spots on the Skin of Participants.

After completion of the simulation and before doffing, the fluorescent markers on the participants were visualized and photographed under UV light. Of 8 participants, 6 had markers on the neck (A and B) and 1 had markers on the ear (C). Distribution of the markers on all participants is shown with each color representing 1 participant (D).

All team members had fluorescent markers on their hair and 4 had markers on their shoes. During the adult and pediatric scenarios, there were 102 and 88, respectively, participant-manikin contacts.

Discussion

Despite personal protective equipment, fluorescent markers were found on the uncovered skin, hair, and shoes of participants after simulations of emergency department management of patients experiencing respiratory distress. The findings suggest that the current recommendations for personal protective equipment may not fully prevent exposures in emergency department settings. Clothing that covers all skin may further diminish exposure risk.

Inhalation of aerosols and exposure risks associated with doffing were not evaluated in this study. The small number of participants, the simulated health care setting, and the surrogate measures of exposure are the primary limitations. Because this was a simulation study using manikins, it is uncertain how the results might apply to actual patient care.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Adalja AA, Toner E, Inglesby TV. Priorities for the US health community responding to COVID-19. JAMA. Published online March 3, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Published February 27, 2020. Accessed March 21, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331215/WHO-2019-nCov-IPCPPE_use-2020.1-eng.pdf

- 3.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for patients with suspected or confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in healthcare settings. Accessed March 21, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/infection-control/control-recommendations.html

- 4.Verbeek JH, Rajamaki B, Ijaz S, et al. Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7:CD011621. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011621.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lockhart SL, Naidu JJ, Badh CS, Duggan LV. Simulation as a tool for assessing and evolving your current personal protective equipment: lessons learned during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Can J Anaesth. Published online March 27, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01638-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anaesth. Published online February 12, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01591-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]