There is a desperate need for effective therapies and vaccines for SARS-CoV-2 to mitigate the growing economic crisis that has ensued from societal lockdown. Vaccines are being developed at an unprecedented speed and are already in clinical trials, without preclinical testing for safety and efficacy. Yet, safety evaluation of candidate vaccines must not be overlooked.

Subject terms: SARS-CoV-2

Here, Iwasaki and Yang highlight the potential dangers of inducing suboptimal antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2. They stress the need for proper safety evaluation of candidate vaccines for COVID-19.

SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV share 79.6% sequence identity, use the same entry receptor (ACE2) and cause similar acute respiratory syndromes. As such, key insights from studies of the immune response to SARS-CoV should be considered when developing vaccines for SARS-CoV-2. Crucially, although antibody titres are generally used as correlates of protection, high antibody titres and early seroconversion are reported to correlate with disease severity in patients with SARS1.

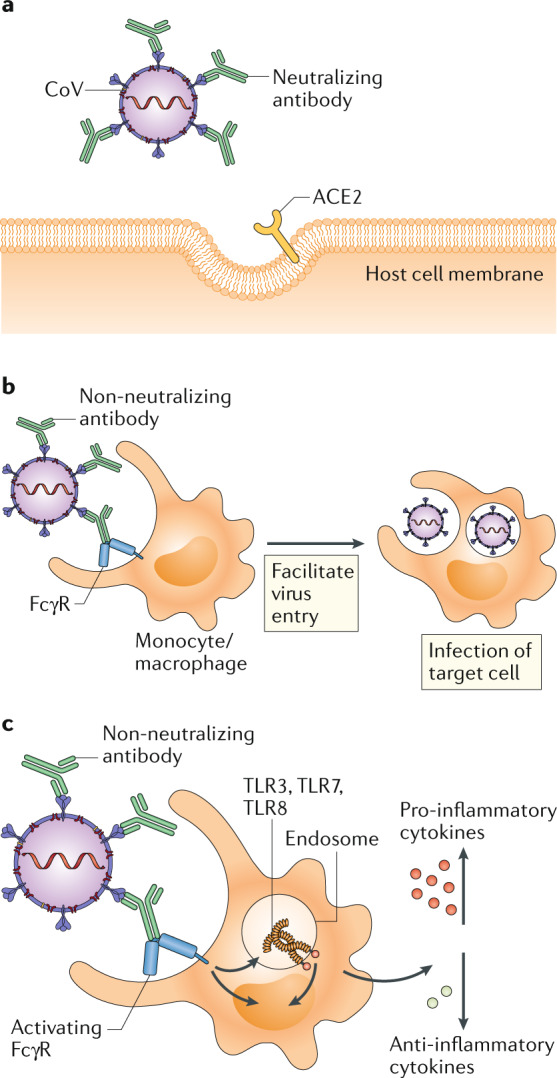

The quality and quantity of the antibody response dictates functional outcomes. High-affinity antibodies can elicit neutralization by recognizing specific viral epitopes (Fig.1a). Neutralizing antibodies are defined in vitro by their ability to block viral entry, fusion or egress. In vivo, neutralizing antibodies can function without additional mediators, although the Fc region is required for neutralization of influenza virus2. In the case of SARS-CoV, viral docking on ACE2 on host cells is blocked when neutralizing antibodies, for example, recognize the receptor-binding domain (RBD) on the spike (S) protein3. S protein-mediated viral fusion can be blocked by neutralizing antibodies targeting the heptad repeat 2 (HR2) domain3. In addition, neutralizing antibodies can interact with other immune components, including complement, phagocytes and natural killer cells. These effector responses can aid in pathogen clearance, with engagement of phagocytes shown to enhance antibody-mediated clearance of SARS-CoV4. However, in rare cases, pathogen-specific antibodies can promote pathology, resulting in a phenomenon known as antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE).

Fig. 1. Potential outcomes of antibody response to coronavirus.

a | In antibody-mediated viral neutralization, neutralizing antibodies binding to the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the viral spike protein, as well as other domains, prevent virus from docking onto its entry receptor, ACE2. b | In antibody-dependent enhancement of infection, low quality, low quantity, non-neutralizing antibodies bind to virus particles through the Fab domains. Fc receptors (FcRs) expressed on monocytes or macrophages bind to Fc domains of antibodies and facilitate viral entry and infection. c | In antibody-mediated immune enhancement, low quality, low quantity, non-neutralizing antibodies bind to virus particles. Upon engagement by the Fc domains on antibodies, activating FcRs with ITAMs initiate signalling to upregulate pro-inflammatory cytokines and downregulate anti-inflammatory cytokines. Immune complexes and viral RNA in the endosomes can signal through Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), TLR7 and/or TLR8 to activate host cells, resulting in immunopathology.

Antibody-dependent enhancement

Although antibodies are generally protective and beneficial, the ADE phenomenon is documented for dengue virus and other viruses. In SARS-CoV infection, ADE is mediated by the engagement of Fc receptors (FcRs) expressed on different immune cells, including monocytes, macrophages and B cells5,6. Pre-existing SARS-CoV-specific antibodies may thus promote viral entry into FcR-expressing cells (Fig. 1b). This process is independent of ACE2 expression and endosomal pH and proteases, suggesting distinct cellular pathways of ACE2-mediated and FcR-mediated viral entry6. There is no evidence that ADE facilitates the spread of SARS-CoV in infected hosts. In fact, infection of macrophages through ADE does not result in productive viral replication and shedding7. Instead, internalization of virus–antibody immune complexes can promote inflammation and tissue injury by activating myeloid cells via FcRs5. Virus introduced into the endosome through this pathway will likely engage the RNA-sensing Toll-like receptors (TLRs) TLR3, TLR7 and TLR8 (Fig. 1c). Uptake of SARS-CoV through ADE in macrophages led to elevated production of TNF and IL-6 (ref.5). In mice infected with SARS-CoV, ADE was associated with decreased levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and TGFβ and increased levels of the pro-inflammatory chemokines CCL2 and CCL3 (ref.8). Furthermore, immunization of non-human primates with a modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) virus encoding the full-length S protein of SARS-CoV promoted activation of alveolar macrophages, leading to acute lung injury9.

Protective versus pathogenic antibodies

Multiple factors determine whether an antibody neutralizes a virus and protects the host or causes ADE and acute inflammation. These include the specificity, concentration, affinity and isotype of the antibody. Viral vector vaccines encoding SARS-CoV S protein and nucleocapsid (N) protein provoke anti-S and anti-N IgG in immunized mice, respectively, to a similar extent. However, upon re-challenge, N protein-immunized mice show significant upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion, increased neutrophil and eosinophil lung infiltration, and more severe lung pathology8. Similarly, antibodies targeting different epitopes on the S protein may vary in their potential to induce neutralization or ADE. For example, antibodies reactive to the RBD domain or the HR2 domain of the S protein induce better protective antibody responses in non-human primates, whereas antibodies specific for other S protein epitopes can induce ADE10. In vitro data suggest that for cells expressing FcRs, ADE occurs when antibody is present at a low concentration but dampens at the high-concentration range. Meanwhile, increasing antibody concentrations promotes SARS-CoV neutralization by blocking viral entry into host cells6. For other viruses, high-affinity antibodies capable of blocking receptor binding tend to not induce ADE.

In the ‘multiple hit’ model of neutralization, the virus-blocking effect correlates with the number of antibodies coating the virion, which is collectively affected by antibody concentration and affinity11. Monoclonal antibodies with higher affinity for the envelope (E) protein of West Nile Virus (WNV) induced better protection in mice receiving a lethal dose of WNV11. For a given concentration of antibody and a specific targeting domain, the stoichiometry of antibody engagement on a virion is dependent on the strength of interaction between antibody and antigen. ADE is induced when the stoichiometry is below the threshold for neutralization. Therefore, higher affinity antibodies can reach that threshold at a lower concentration and mediate better protection11.

Antibody isotypes control their effector functions. IgM is considered more pro-inflammatory as it activates complement efficiently. IgG subclasses modulate immune responses via the engagement of different FcRs. Most FcγRs signal through ITAMs, but FcγRIIb contains an ITIM on its cytoplasmic tail that mediates an anti-inflammatory response. Ectopic expression of FcγRIIa and FcγRIIb, but not of FcγRI or FcγRIIIa, induced ADE of SARS-CoV infection6. Allelic polymorphisms in FcγRIIa are associated with SARS pathology, and individuals with an FcγRIIa isoform that binds to both IgG1 and IgG2 were found to develop more severe disease than individuals with FcγRIIa that only binds to IgG2 (ref.12).

Vaccine approaches

It is crucial to determine which vaccines and adjuvants can elicit protective antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2. Previous studies have shown that the immunization of mice with inactivated whole SARS-CoV13, the immunization of rhesus macaques9 with MVA-encoded S protein and the immunization of mice with DNA vaccine encoding full-length S protein14 could induce ADE or eosinophil-mediated immunopathology to some extent, possibly owing to low quality and quantity of antibody production. Additionally, we need to consider whether a vaccine is safe and effective in aged hosts. For instance, double-inactivated SARS-CoV vaccine failed to induce neutralizing antibody responses in aged mice13. Furthermore, although an alum-adjuvanted double-inactivated SARS-CoV vaccine elicited higher antibody titres in aged mice, it skewed the IgG subclass toward IgG1 instead of IgG2, which was associated with a T helper 2 (TH2)-type immune response, enhanced eosinophilia and lung pathology13. By contrast, studies in mice showed that subunit or peptide vaccines that focus the antibody response against specific epitopes within the RBD of the S protein conferred protective antibody responses3. In addition, live attenuated SARS-CoV vaccine induced protective immune responses in aged mice15. Routes of vaccine administration can further affect vaccine efficacy. Compared with the intramuscular route, intranasal administration of a recombinant adeno-associated virus vaccine encoding SARS-CoV RBD induced significantly higher titres of mucosal IgA in the lung and reduced lung pathology upon challenge with SARS-CoV3.

Concluding remarks

There are now multiple vaccine candidates (including nucleic acid vaccines, viral vector vaccines and subunit vaccines) in the preclinical and clinical trial stages as researchers and institutes from all over the world come together to accelerate the development of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Recent studies of antibody responses in patients with COVID-19 have associated higher titres of anti-N IgM and IgG at all time points following the onset of symptoms with a worse disease outcome16. Moreover, higher titres of anti-S and anti-N IgG and IgM correlate with worse clinical readouts and older age17, suggesting potentially detrimental effects of antibodies in some patients. However, 70% of patients who recovered from mild COVID-19 had measurable neutralizing antibodies that persisted upon revisit to the hospital18. Thus, insights gained from studying the antibody features that correlate with recovery as opposed to worsening of disease will inform the type of antibodies to assess in vaccine studies. We argue that ADE should be given full consideration in the safety evaluation of emerging candidate vaccines for SARS-CoV-2. In addition to vaccine approaches, monoclonal antibodies could be used to tackle this virus. Unlike vaccine-induced antibodies, monoclonal antibodies can be engineered with molecular precision. Safe and effective neutralizing antibodies could be produced on a mass-scale for delivery to populations across the world in the coming months.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank H. W. Virgin, A. Arvin, J. Bloom and R. Medzhitov for helpful discussions.

Author contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Lee N, et al. Anti-SARS-CoV IgG response in relation to disease severity of severe acute respiratory syndrome. J. Clin. Virol. 2006;35:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiLillo DJ, et al. Broadly neutralizing anti-influenza antibodies require Fc receptor engagement for in vivo protection. J. Clin. Invest. 2016;126:605–610. doi: 10.1172/JCI84428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du L, et al. The spike protein of SARS-CoV — a target for vaccine and therapeutic development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:226–236. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yasui F, et al. Phagocytic cells contribute to the antibody-mediated elimination of pulmonary-infected SARS coronavirus. Virology. 2014;454:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang SF, et al. Antibody-dependent SARS coronavirus infection is mediated by antibodies against spike proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014;451:208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.07.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaume M, et al. Anti-severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike antibodies trigger infection of human immune cells via a pH- and cysteine protease-independent FcγR pathway. J. Virol. 2011;85:10582–10597. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00671-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yip MS, et al. Antibody-dependent enhancement of SARS coronavirus infection and its role in the pathogenesis of SARS. Hong Kong Med. J. 2016;22:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yasui F, et al. Prior immunization with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) nucleocapsid protein causes severe pneumonia in mice infected with SARS-CoV. J. Immunol. 2008;181:6337–6348. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu L, et al. Anti-spike IgG causes severe acute lung injury by skewing macrophage responses during acute SARS-CoV infection. JCI Insight. 2019;4:e123158. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.123158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Q, et al. Immunodominant SARS coronavirus epitopes in humans elicited both enhancing and neutralizing effects on infection in non-human primates. ACS Infect. Dis. 2016;2:361–376. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.6b00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierson TC, et al. Structural insights into the mechanisms of antibody-mediated neutralization of flavivirus infection: implications for vaccine development. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan FF, et al. Influence of FcγRIIA and MBL polymorphisms on severe acute respiratory syndrome. Tissue Antigens. 2005;66:291–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2005.00476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolles M, et al. A double-inactivated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus vaccine provides incomplete protection in mice and induces increased eosinophilic proinflammatory pulmonary response upon challenge. J. Virol. 2011;85:12201–12215. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06048-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Z-y, et al. Evasion of antibody neutralization in emerging severe acute respiratory syndrome coronaviruses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409065102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graham RL, et al. A live, impaired-fidelity coronavirus vaccine protects in an aged, immunocompromised mouse model of lethal disease. Nat. Med. 2012;18:1820–1826. doi: 10.1038/nm.2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan W, et al. Viral kinetics and antibody responses in patients with COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.24.20042382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang H-w, et al. Global profiling of SARS-CoV-2 specific IgG/IgM responses of convalescents using a proteome microarray. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.20.20039495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu F, et al. Neutralizing antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in a COVID-19 recovered patient cohort and their implications. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.30.20047365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]