Abstract

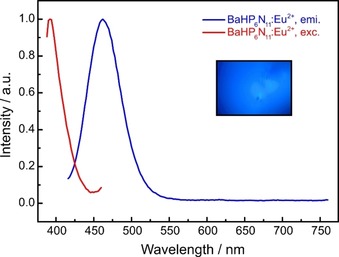

Barium imidonitridophosphate BaP6N10NH was synthesized at 5 GPa and 1000 °C with a high‐pressure high‐temperature approach using the multianvil technique. Ba(N3)2, P3N5 and NH4Cl were used as starting materials, applying a combination of azide and mineralizer routes. The structure elucidation of BaP6N10NH (P63, a=7.5633(11), c=8.512(2) Å, Z=2) was performed by a combination of transmission electron microscopy and single‐crystal diffraction with microfocused synchrotron radiation. Phase purity was verified by Rietveld refinement. 1H and 31P solid‐state NMR and FTIR spectroscopy are consistent with the structure model. The chemical composition was confirmed by energy‐dispersive X‐ray spectroscopy and CHNS analyses. Eu2+‐doped samples of BaP6N10NH show blue emission upon excitation with UV to blue light (λ em=460 nm, fwhm=2423 cm−1) representing unprecedented Eu2+‐luminescence of an imidonitride.

Keywords: high-pressure chemistry, high-temperature chemistry, imidonitridophosphates, luminescence, microfocused synchrotron radiation

The imidonitridophosphate BaP6N10NH was synthesized via high‐pressure high‐temperature approach at 4 GPa and 1150 °C. The crystal structure was determined from single‐crystal diffraction data collected with microfocused synchrotron radiation. Doping of the title compound with Eu2+ leads to unprecedented observation of luminescence from a Eu2+‐doped imidonitridophosphate.

Introduction

The ongoing development of advanced synthesis strategies, enabled the discovery of numerous silicate‐analogous tetrahedra‐based compound classes, of which nitridophosphates are a prominent example.1 Nitridophosphates show structural similarities with oxosilicates as the element combination P/N is isoelectronic to Si/O. Compared to oxosilicates, the synthetic access to nitridophosphates is challenging, because on the one hand high temperatures (often >1000 °C) are needed for rearranging P−N bonds, but on the other hand P3N5, the most important starting material, decomposes above 850 °C. This problem can be resolved with high‐pressure high‐temperature syntheses according to the principle of Le Chatelier. Despite their challenging syntheses, the structural chemistry of nitridophosphates is intriguing, as they can reach even higher degrees of condensation (i.e., atomic ratio κ of tetrahedra centers and ligands) than oxosilicates (κ(P3N5)=0.6, κ(SiO2)=0.5).2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Thus, nitridophosphates feature triply‐bridging N3 atoms or even edge‐sharing PN4 tetrahedra.9 Moreover, nitridophosphates have recently been investigated as host materials for Eu2+‐doped phosphors.10, 11, 12 Although the number of nitridophosphate‐based phosphors is still limited, the known examples almost cover the entire visible spectrum. For example, MP2N4:Eu2+ (M=Ca, Sr, Ba) shows emissions from 450 to 570 nm, featuring full width at half‐maximum (fwhm) values comparable to established nitride‐based phosphor materials.10 Furthermore, Eu2+‐doped quaternary zeolite‐like nitridophosphates Ba3P5N10 X (X=Cl, Br, I) have been investigated concerning their luminescence properties.11, 12 Ba3P5N10Br, for example, has been discussed as a natural‐white‐light single emitter.12

In contrast, quaternary imidonitridophosphates, which have been discussed as possible intermediates on the reaction pathway to highly condensed nitridophosphates, are completely unexplored concerning their luminescence properties.8 These H‐containing compounds can be synthesized using starting materials like amides, NH4Cl, or the underlying ternary imide nitride HPN2.13, 14, 15, 16, 17 For years, only the less condensed alkali metal amide/imide compounds Cs5P(NH)4(NH2)2, Rb8[P4N6(NH)4](NH2)2 and Na10[P4N4(NH)6](NH2)6(NH3)0.5 have been known, showing discrete tetrahedra and adamantane‐like [P4N10−x(NH)x](10−x)− cages, respectively.13, 14, 15 The highly condensed alkaline earth metal imidonitridophosphates MH4P6N12 (M=Mg, Ca, Sr) were the first representatives showing layered network structure types.8, 17 In framework‐type SrP3N5NH, internal H bonds lead to structure types that are not related to isoelectronic SrP3N5O compounds.16

Herein, we report on the highly condensed imidonitridophosphate BaP6N10NH (κ=0.55), initially observed as microcrystalline particles in multiphase samples. Structure elucidation by X‐ray diffraction with microfocused synchrotron radiation revealed an unprecedented structure type. The results enabled the targeted synthesis of phase‐pure products, leading to first studies on the luminescence properties of Eu2+‐doped imidonitridophosphates.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

BaP6N10NH was initially observed in a heterogeneous sample synthesized by high‐pressure high‐temperature reaction at 4 GPa and 1150 °C using a hydraulic press including a modified Walker‐type multianvil apparatus.18, 19, 20, 21, 22 Starting from Ba(N3)2, P3N5, and NH4Cl, a colorless microcrystalline sample was obtained. Stoichiometric reactions according to Equation (1) did not lead to phase‐pure products.

| (1) |

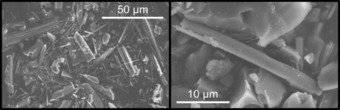

The highest yield was obtained with a slight excess of Ba(N3)2 (1.2 equiv.) and a noticeable excess of NH4Cl (4 equiv.). With NH4Cl acting as hydrogen source and as a mineralizer, this approach is a combination of azide and mineralizer routes. EuCl2 (1 mol %) was added as dopant. The title compound was isolated as an air‐ and moisture‐stable colorless solid (yield per batch ≈35 mg) and was washed with de‐ionized water after synthesis. Optimized syntheses yielded rod‐like crystals with an edge length up to 30 μm (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

SEM images of BaP6N10NH crystals with a maximum length of about 30 μm.

Structure determination

Due to the microcrystalline and multiphase character of the original sample, neither conventional single‐crystal X‐ray diffraction nor structure solution from powder X‐ray diffraction data were applicable. Hence, a combination of transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and microfocused synchrotron radiation was applied.23 Small crystallites (needles up to 8 μm in length with diameters of ca. 1–2 μm) of the target phase were identified by selected‐area electron diffraction (see Supporting Information, Figure S1) and EDX analysis. The crystallites' positions were documented on finder grids and transferred to the synchrotron beamline (ID11, ESRF, Figure S2). Subsequent structure determination was based on single‐crystal diffraction data collected with a microfocused synchrotron beam with a diameter of ca. 1×2 μm.

The crystal structure of the title compound was initially solved by direct methods and refined as BaP6 X 11 (X=O, N) in the hexagonal space group P63 (no. 173) with unit cell dimensions of a=7.5585(1) and c=8.5106(1) Å. The preliminary sum formula BaP6 X 11 (X=O, N) allows for two conceivable charge‐balanced compositions such as BaP6N10O or BaP6N10NH. Although small maxima of residual electron densities were observed at reasonable N−H distances to N1, N2, and N5, they could not be refined, probably because H atoms are disordered on these three suitable N2 positions, of which each single one may only be occupied by one third of H on average. Based on the results of solid‐state NMR and FTIR spectroscopy, BaP6N10NH turned out to be the correct sum formula (Figure 3 and Figure S3). All located atoms were refined anisotropically. The summarized crystallographic data are given in Table S1. Atom positions and anisotropic displacement parameters are listed in Tables S2 and S3 (see Supporting Information). CSD 1942108 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from FIZ Karlsruhe via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

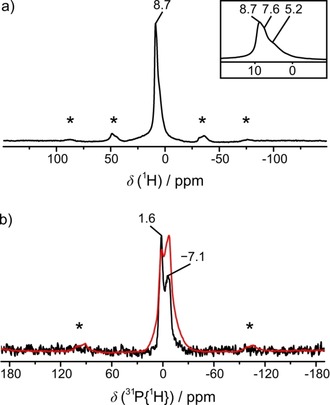

Figure 3.

Solid‐state NMR spectra of BaP6N10NH, measured at a sample spinning frequency of 50 kHz. a) 1H MAS NMR spectrum: One wide band can be identified as three individual signals with shifts of 5.2, 7.6, and 8.7 ppm in the magnified area. b) 31P MAS (black) and 31P{1H} (red) MAS cross polarization NMR spectra: Both show two peaks with chemical shifts of −7.1 and 1.6 ppm. Spinning side bands are marked with asterisks.

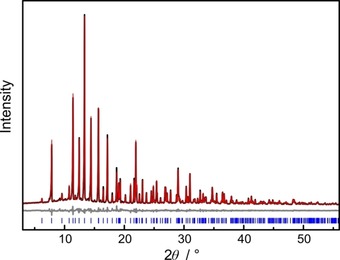

Based on the refined single‐crystal structure of BaP6N10NH, Rietveld refinement of powder X‐ray diffraction data confirms phase purity (Figure 2 and Table S4 in the Supporting Information). For the verification of the chemical composition, energy‐dispersive X‐ray spectroscopy (EDX) was carried out. No elements other than Ba, P, N and O were detected. The determined atomic ratio of Ba : P : N≈1 : 6 : 11 corresponds to the expected sum formula (see Table S5). O was only detected in trace amounts at some points and can most likely be attributed to surface hydrolysis of the sample. CHNS analysis (Table S6) yielded a weight percentage of N that agrees well with the theoretical value, while the weight percentage of H is slightly higher than expected, again a hint at surface hydrolysis.

Figure 2.

Rietveld refinement of BaP6N10NH; observed (black) and simulated (red) powder X‐ray diffraction patterns and difference profile (grey). Positions of Bragg reflections of BaP6N10NH (blue) are marked with vertical blue bars.

The Fourier‐transform infrared (FTIR) spectrum shows a broad vibration band with significant intensity from 2700–3400 cm−1 (see Supporting Information, Figure S3). This can be attributed to N−H valence modes and is comparable to other known imidonitridophosphates.8, 16, 17 Further absorption bands with very strong intensities are visible in the fingerprint region (400–1500 cm−1, see Figure S3). They can be assigned to symmetric and asymmetric P‐N‐P stretching modes.

As another verification for the presence of H atoms and the structure model in general, solid‐state nuclear magnetic resonance measurements (NMR) were performed. The focus of these experiments was on H atoms in order to supplement the results of X‐ray diffraction data. Therefore, 1H, 31P, and 31P{1H} magic angle spinning (MAS) experiments were carried out. At first glance, the observed 1H MAS spectrum shows one signal at 8.7 ppm, which is rather broad in comparison to those of other imidonitridophosphates (Figure 3 a).8, 16, 17 In fact, this band is composed of three signals with shifts of δ=5.2, 7.6, and 8.7 ppm, which can be assigned to the title compound (magnification in Figure 3 a). This observation is in line with the assumption that H is statistically bound to three N atoms. The 31P MAS spectrum shows two signals with chemical shifts of δ=−7.1 and 1.6 ppm (Figure 3 b, black). As these signals remain in the 31P{1H} cross‐polarization spectrum, the corresponding P atoms seem to be located in a hydrogen‐containing environment, and can thus be assigned to BaP6N10NH (Figure 3 b, red).

Structure description

BaP6N10NH can be classified as a highly condensed compound and shows the highest degree of condensation among quaternary imidonitridophosphates (κ=n(P):n(N)=0.55) reaching almost the degree of condensation in HP4N7 (κ=0.57).5, 6, 7 The structure is built up from all‐side vertex‐sharing PN4 tetrahedra and can be described as a three‐dimensional network of interconnected propeller‐like [P3N10] subunits consisting of three PN4 tetrahedra linked by a threefold bridging N atom like that observed in β‐HP4N7.6 While these subunits are linked directly to each other as well as by additional bridging PN4 tetrahedra in β‐HP4N7 forming 3‐, 4‐, and 6‐rings, the BaP6N10NH structure‐type is exclusively built up from interconnected [P3N10] subunits forming 3‐ and 9‐rings.6 Thereby the tetrahedra of one subunit are centered by the same P site in BaP6N10NH (Figure 4, P1: grey; P2: blue).

Figure 4.

Propeller‐like [P3N10] units of P1 and P2 as smallest building units of the crystal structure of BaP6N10NH.

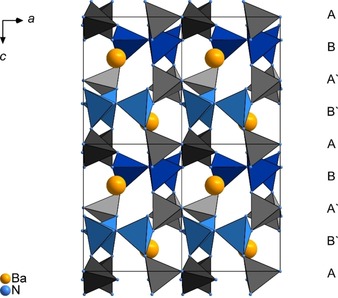

Each [P3N10] unit is linked to six further subunits, which are centered by the other P site. This arrangement leads to a stacking of the propeller‐like building blocks along [0 0 1] with an order of ABA‘B‘ABA‘B‘ (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Projection of the crystal structure of BaP6N10NH along [0 1 0]. Color coding: Ba: yellow, N: blue, P1 centered tetrahedra: grey, P2 centered tetrahedra: blue; unit cells are indicated.

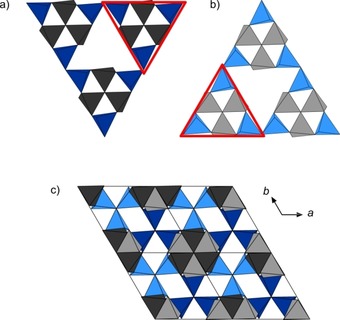

Furthermore, the combinations of the slabs A/B (dark colors) and the equivalent ones A‘/B‘ (bright colors) can be described as layered PN4 substructures, which are related by the 63 screw axis along [0 0 1] (Figures 6 a and 6 b).

Figure 6.

a) Triangular [P6N16] units built up from layers A and B b) Triangular [P6N16] units built up from layers A‘ and B‘ c) Projection of the structure of BaP6N10NH along [0 0 1]. Color coding: P1 centered tetrahedra: grey, P2 centered tetrahedra: blue.

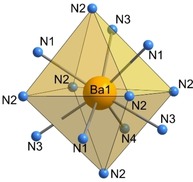

Within these layers, the [P3N10] subunits form larger triangular [P6N16] building blocks which are connected through common vertices (red triangles, Figures 6 a and 6 b). In an alternating stacking sequence of these layers, the grey tetrahedra (P1 centered) form columns whereas the blue [P3N10] units of one layer fill up the triangular channels of the other one (Figure 6 c). In the resulting framework, P−N distances and N‐P‐N angles are similar to values from other alkaline earth metal nitridophosphates (P−N: 1.590(3)–1.735(1) Å, N‐P‐N: 102.3(1)–114.1(1)°).8, 10, 24 Thereby, the elongated P−N distances can be attributed to the triply bridging N3 atoms (P(1)−N(5), P(2)−N(4)), which is in accordance with distances observed in β‐HP4N7.6 Further information about bond lengths and angles is summarized in Table S7 (see Supporting Information). The topology of the network is represented by the point symbol (32.52.64.72)(33.42.53.62), which has not been observed as yet.25 Due to the described arrangement of PN4 tetrahedra, the Ba atoms occupy one single crystallographic site which is coordinated by 13 N atoms in a slightly distorted sevenfold capped octahedron (Figure 7). Ba−N distances range from 2.884(3)–3.363(2) Å and agree with known barium nitridophosphates, as well as with the sum of the ionic radii.24, 26, 27

Figure 7.

Coordination of Ba by 13 N atoms in a slightly distorted sevenfold capped octahedron in BaP6N10NH.

Temperature dependent X‐ray diffraction

In order to investigate the thermal stability of BaP6N10NH, temperature dependent X‐ray diffraction measurements were carried out up to 1000 °C under Ar atmosphere. BaP6N10NH is apparently stable over the entire temperature range, featuring no significant changes in the diffraction pattern (Figure S4). The evolution of the lattice parameters upon heating was determined by Rietveld refinements of selected temperature‐dependent PXRD patterns. The parameters a and c (+0.8 %, +0.6 %) increase almost linearly, resulting in a thermal expansion of the unit cell by 2.2 % in volume at 1000 °C with respect to ambient temperature (Table S8 and Figure S5).

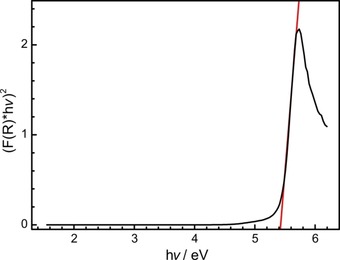

UV/Vis reflectance spectroscopy

The optical properties of BaP6N10NH were investigated by diffuse reflectance measurements. The corresponding spectrum shows an absorption band at around 250 nm (Supporting Information, Figure S6). The Kubelka–Munk function F(R)=(1‐R)2/2R, with R representing the reflectance, was used for the conversion of the reflectance spectrum into a pseudo‐absorption spectrum.28 The band gap was then determined by plotting hν versus (F(R)⋅hν)1/n (Tauc plot, Figure 8).29 The resulting Tauc plot shows an approximately linear region for n=1/2 and suggests a direct band gap. Based on the experimental data, the optical band gap can be estimated to ≈5.4 eV by intersecting the aligned tangent of the linear region with the abscissa.

Figure 8.

Tauc plot (black) for non‐doped BaP6N10NH. Red line as a tangent at the inflection points.

Luminescence

Concluding from structural and optical properties, as well as the thermal stability, BaP6N10NH seems to be a promising candidate for a case study on the luminescence properties of imidonitridophosphates, which have not been reported so far. BaP6N10NH:Eu2+ can efficiently be excited by near‐UV to blue light (Figure 9, red). Excitation at 420 nm results in blue emission (λ em=460 nm, fwhm=52 nm/2423 cm−1) for single particles with a nominal Eu content of 1 atom % referred to Ba, making BaP6N10NH:Eu2+ the first luminescent imidonitride. The occurrence of the Eu2+‐luminescence might have different reasons. Although quenching effects of oscillators like X−H (X=O, N, C) were discussed for aromatic organic compounds in the near‐IR range, luminescence can be observed if it does not excite any overtone of the vibrational X−H modes.30, 31, 32 In the case of BaP6N10NH, an experimental evaluation could therefore not be performed, as the respective emission is located in the blue spectral range and corresponding wavenumbers (ν ≈21.700 cm−1) would require absorption experiments for the fifth (n=6) or sixth (n=7) overtone. The low intensities of high‐order overtones, the low resolution of solid‐state IR spectroscopy and the intrinsic broad bands for N−H valence modes preclude such investigations. Another reason for the visible emission might be given by the low concentration of potentially quenching N−H groups in BaP6N10NH. This concentration can be characterized by the ratio of H‐bonding to non‐H‐bonding N atoms (NH/N) and amounts to 1:10 for the title compound. All other known imidonitridophosphates show significantly higher NH/N values (MH4P6N12≡MP6N8(NH)4: 1/2; SrP3N5NH: 1/5).8, 16, 17 The emission spectrum of BaP6N10NH:Eu2+ exhibits a single emission band with a maximum at 460 nm and a full width at half maximum (fwhm) of 52 nm/2423 cm−1 (see Figure 9). This single emission band results from the fact that Eu2+ is expected to occupy the single crystallographic Ba site apparent in the crystal structure. With these characteristic values, BaP6N10NH:Eu2+ can be compared to ternary and quaternary all‐nitride Eu2+‐doped nitridophosphates, for example, BaP2N4:Eu2+ (λ em=454, fwhm=2244 cm−1) and BaSr2P6N12:Eu2+ (λ em=456, fwhm=2240 cm−1).10 The similar emission values might be explained by the similar environment of the alkaline earth metals in the mentioned compounds, as BaP2N4:Eu2+ (Ba‐N: 2.78–3.48 Å) and BaSr2P6N12:Eu2+ (M‐N: 2.80–3.40 Å) each exhibit two crystallographic Ba/Sr sites, which are coordinated by twelve N atoms.10

Figure 9.

Normalized excitation (red) and emission (blue) spectra (λ exc=420 nm) of BaP6N10NH:Eu2+.

Conclusions

We report on synthesis and characterization of the first barium imidonitridophosphate BaP6N10NH. Among imidonitridophosphates, it exhibits a very high degree of condensation (κ=0.55) and the smallest NH/N ratio. Its structural framework is built up from condensed [P3N10] units, forming larger triangular [P6N16] building blocks. Orientation and arrangement of the latter reveals cavities occupied by Ba atoms in a 13‐fold coordination by N atoms. As previous reports claim that imidonitridophosphates might be less condensed intermediates on the way to highly condensed ternary nitridophosphates, BaP6N10NH seems to be a promising candidate for access to high degrees of condensation in nitridophosphates.8 Investigations on the luminescence of imidonitridophosphates show that Eu2+‐doped samples of BaP6N10NH exhibit blue emission (λ emi=460 nm, fwhm=2423 cm−1) upon excitation with near UV to blue light and make the title compound the first luminescent imidonitride opening up this compound class for the research field of luminescence. Comparison of the observed values and additional thermal stability up to at least 1000 °C make BaP6N10NH, and imidonitridophosphates in general, promising candidates for new luminescent materials. Future studies may focus on more detailed investigations of the luminescence properties, for example the determination of the quantum efficiency in a Eu2+ concentration series. BaP6N10NH also suggests the existence of isotypic compounds of the lighter alkaline earth metals in order to tune the emission. Additionally, more stoichiometric compositions among this compound class should be investigated due to their luminescence properties, as even these first investigations show interesting features without any optimization. This might also bring more insights concerning the assumption that the NH/N concentration may influence the luminescence properties of solid‐state compounds.

Experimental Section

Synthesis of Ba(N3)2: Synthesis of Ba(N3)2 was carried out with a cation exchanger (Amberlyst 15), based on the synthesis by Suhrmann as modified by Karau.33, 34 Thereby, diluted HN3 was formed in situ by passing an aqueous solution of NaN3 (Acros Organics, 99 %, extra pure) through the cation exchanger. Subsequently, the acidic solution of HN3 was dropped carefully into a stirring suspension of BaCO3 (Sigma Aldrich, 99.995 %, trace metals basis) in H2O. The end of the reaction is reached when the liquid phase turned completely clear. Excess BaCO3 was filtered off and the filtrate was boiled down with a rotary evaporator (50 mbar, 40 °C). Ba(N3)2 was obtained as a colorless powder and recrystallized from acetone for purification. Finally, the product was dried under vacuum and its phase purity was confirmed by FTIR spectroscopy and X‐ray diffraction. Caution: Special care is necessary at handling HN3, as even diluted solutions are potentially explosive. Additionally, poisoning threatens upon inhalation of HN3 vapors.

Synthesis of P3N5: Following Stock und Grüneberg, P4S10 (ca. 8.0 g, Sigma Aldrich 99.99 %) was treated in a tube furnace lined with a silica tube (Ø=5 cm) by a constant flow of dried NH3 (≈3.6 l h−1, Air Liquide 5.0).35 Previously, a silica reaction vessel was placed in the reaction tube and the apparatus was dried under reduced pressure (<10−3 mbar) for 4 h at 1000 °C. P4S10 was carefully loaded into the vessel under Ar counter‐stream. At this point it is important to load a limited amount of the starting material, as otherwise there is danger to clog the silica tube by deposition of by‐products. First, the apparatus was purged with NH3 for 4 h and then heated up to 850 °C within 3 h. The temperature was kept for 4 h and then decreased to room temperature within 3 h again. By flushing with Ar for 1 h the remaining NH3 was removed. P3N5 was obtained as a pale orange product and washed with water, ethanol, and acetone. Phase purity and the absence of possible H containing species were verified by powder X‐ray diffraction and FTIR spectroscopy.

High‐pressure high‐temperature synthesis of BaP6N10NH: BaP6N10NH was synthesized applying a 1000 t press (Voggenreiter, Mainleus, Germany) with a modified Walker‐type multianvil apparatus.18, 19, 20, 21, 22 The synthesis started from NH4Cl, P3N5, and Ba(N3)2. Phase‐pure products required the surplus of NH4Cl and Ba(N3)2. The precise amounts of the starting materials are given in the Supporting Information (Table S9). With Ba(N3)2 as an air‐sensitive starting material, all manipulations were carried out in an argon‐filled glovebox (Unilab, MBraun, Garching, O2<1 ppm, H2O<0.1 ppm) under exclusion of oxygen and moisture. The mixture of the starting materials was ground thoroughly and packed into a cylindrical crucible made of hexagonal boron nitride (HeBoSint® S100, Henze, Kempten, Germany). The crucible was transferred into a Cr2O3‐doped (5 %) MgO octahedron (edge length 18 mm, Ceramic Substrates & Components, Isle of Wight, UK), which served as pressure medium. The octahedron was drilled through centrically and filled up with a ZrO2 sleeve (Cesima Ceramics, Wust‐Fischbeck. Germany), a Mo plate, a MgO plate (Cesima Ceramics, Wust‐Fischbeck, Germany) and two graphite tubes (Schunk Kohlenstofftechnik GmbH, Gießen, Germany). Thereby, the ZrO2 sleeve serves as thermal insulator, MgO as spacer, and the combination of two thin graphite tubes with different lengths was used as electrical resistance furnaces with minimum temperature gradient. The Mo plate ensures the electrical contact of the graphite tubes to the surrounding setup. After inserting the crucible, the symmetric assembly was completed by sealing with a hexagonal boron nitride cap, a further MgO plate, and a second Mo plate, closing the circuit. The distribution of the uniaxial pressure, exerted by a 1000 t press, was handled by the usage of the mentioned Walker‐type apparatus and an inserted setup of eight Co‐doped (7 %) WC cubes (Hawedia, Marklkofen, Germany) with truncated edges (edge length 11 mm). For electrical insulation, half of the latter were prepared with Bristol board (369 g m−2) and half with a PTFE film (Vitaflon Technische Produkte GmbH, Bad Kreuznach, Germany). Pyrophyllite gaskets (Ceramic Substrates & Components, Isle of Wight, UK) were used to avoid the outflow of the pressure medium.36 During synthesis BaP6N10NH was compressed to 4 GPa at room temperature and subsequently heated up to 1150 °C within 60 min. The temperature was held for further 60 min and then cooled down to room temperature within 180 min. After decompression of the setup the title compound was recovered as a colorless and crystalline solid, non‐sensitive towards air and moisture.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy‐dispersive X‐ray spectroscopy (EDX): The investigations of the morphology and chemical composition of the title compound were performed on a Dualbeam Helios Nanolab G3 UC (FEI, Hillsboro) with a X‐Max 80 SDD EDX detector (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon). Samples were fixed on adhesive carbon pads and additionally coated with carbon using an electron beam evaporator (BAL‐TEC MED 020, Bal Tec AG), in order to provide electrical conductivity.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM): A small part of the sample was ground in an agate mortar, suspended in absolute ethanol and then drop‐cast on a copper finder grid (S160NH2C, PLANO GmbH, Wetzlar). Crystals were selected using a FEI Tecnai G20 transmission electron microscope (TEM) with thermal emitter (LaB6) operating at 200 keV. SAED patterns and bright‐field images were recorded using a TVIPS camera. The elemental composition of individual crystallites was investigated by energy‐dispersive X‐ray spectroscopy (EDX, EDAX Apollo XLT detector). Bright‐field images of the crystals at different magnifications aided in positioning the crystallites in the synchrotron beam.

Single‐crystal X‐ray diffraction: Single‐crystal diffraction data were collected at ID11, ESRF, Grenoble, on a Symétrie Hexapods Nanopos device (λ=0.309 Å), after recovering the preselected crystal by optical centering and fluorescence scans. The collected data were integrated with CrysAlisPro and SADABS was used for semiempirical absorption correction.37, 38 A correction for incomplete absorption of X‐ray radiation in the phosphor of the CCD detector was applied as well.39 The program package SHELX‐2014 was used for structure determination and least‐squares refinement.40

CCDC https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/services/structures?id=doi:10.1002/chem.201905082 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/ / FIZ Karlsruhe joint deposition service.

CHNS analysis: A Vario Micro Cube device (Elementar, Langenselbold, Germany) was used to perform elemental analysis.

FTIR spectroscopy: A sample of BaP6N10NH was ground with KBr and compressed to a disk. An IFS 66 v/S spectrometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) was used to record the FTIR spectrum.

Powder X‐ray diffraction: A Stadi P powder diffractometer (STOE, Darmstadt, Germany) was used to collect data in parafocussing Debye–Scherer geometry. The diffractometer was equipped with a Ge(111) monochromator (Mo radiation) and a MYTHEN 1 K Si strip detector (Dectris, Baden, Switzerland; angular range Δ2θ=12.5°). Samples were filled into a glass capillary with 0.3 mm diameter and a wall‐thickness of 0.01 mm (Hilgenberg GmbH, Malsfeld, Germany) for executing measurements. Rietveld refinements were carried out with the TOPAS Academic 6.1 package, using the fundamental parameters approach (direct convolution of source emission profiles, axial instrument contributions, and crystallite size and microstrain effects).41 While the background was modeled with a shifted Chebychev function, a fourth‐order spherical harmonics model was applied to describe the potential preferred orientation of the block‐like crystallites.

Solid‐state NMR spectroscopy: The 1H resonance of 1 % Si(CH3)4 in CDCl3 was used as an external secondary reference, using the Ξ value for 31P relative to 85 % H3PO4 as reported by the IUPAC.42 The solid‐state MAS NMR experiments were carried out on a DSX Avance 500 spectrometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with a commercial double‐resonance MAS probe, operating at a field strength of 11.7 T with a 2.5 mm ZrO2 rotor at a spinning frequency of 50 kHz. Relaxation times were determined by saturation recovery measurements.

UV/Vis Spectroscopy: Diffuse reflectance UV/Vis spectroscopy measurements were performed on a Jasco V‐650 UV/vis spectrophotometer with a deuterium and a halogen lamp (JASCO, Pfungstadt, Germany, Czerny‐Turner monochromator with 1200 lines mm−1, concave grating, photomultiplier tube detector).

Luminescence: For luminescence measurements, small particles of Eu2+‐doped samples of BaP6N10NH were sealed in fused silica capillaries. The measurements were performed on a HORIBA Fluoromax4 spectrofluorimeter system, connected to an Olympus BX51 microscope via optical fibers. The excitation wavelength was λ exc=420 nm and the emission spectra were recorded in a range from 400 to 800 nm with a step size of 2 nm.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

We thank Christian Minke for EDX and NMR measurements. Furthermore, we thank Dr. Thomas Bräuniger (both at Department of Chemistry of LMU Munich) for help with NMR experiments. Moreover, we thank Volker Weiler (Lumileds Phosphor Center Aachen) for performing luminescence measurements. We also thank the ESRF, Grenoble, for granting beamtime (project CH‐5149). Dr. Christopher Benndorf, Markus Nentwig and Christina Fraunhofer are acknowledged for help during the beamtime.

S. Wendl, L. Eisenburger, M. Zipkat, D. Günther, J. P. Wright, P. J. Schmidt, O. Oeckler, W. Schnick, Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 5010.

References

- 1. Kloß S. D., Schnick W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 7933–7944; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 8015–8027. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Horstmann S., Irran E., Schnick W., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1998, 624, 620–628. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Horstmann S., Irran E., Schnick W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36, 1873–1875; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1997, 109, 1938–1940. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Landskron K., Huppertz H., Senker J., Schnick W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2643–2645; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2001, 113, 2713–2716. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Horstmann S., Irran E., Schnick W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36, 1992–1994; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1997, 109, 2085–2087. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baumann D., Schnick W., Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 7977–7982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baumann D., Schnick W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 14490–14493; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 14718–14721. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wendl S., Schnick W., Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 15889–15896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Superscripted numbers in square brackets following element symbols give coordination numbers.

- 10. Pucher F. J., Marchuk A., Schmidt P. J., Wiechert D., Schnick W., Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 6443–6448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marchuk A., Wendl S., Imamovic N., Tambornino F., Wiechert D., Schmidt P. J., Schnick W., Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 6432–6441. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marchuk A., Schnick W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 2383–2387; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 2413–2417. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jacobs H., Golinski F., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1994, 620, 531–534. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Golinski F., Jacobs H., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1995, 621, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jacobs H., Pollock S., Golinski F., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1994, 620, 1213–1218. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vogel S., Schnick W., Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 14275–14281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marchuk A., Celinski V. R., Schmedt auf der Günne J., Schnick W., Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 5836–5842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kawai N., Endo S., Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1970, 41, 1178–1181. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Walker D., Carpenter M. A., Hitch C. M., Am. Mineral. 1990, 75, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Walker D., Am. Mineral. 1991, 76, 1092–1100. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rubie D. C., Phase Transitions 1999, 68, 431–451. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huppertz H., Z. Kristallogr. 2004, 219, 330–338. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fahrnbauer F., Rosenthal T., Schmutzler T., Wagner G., Vaughan G. B. M., Wright J. P., Oeckler O., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 10020–10023; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 10158–10161. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Karau F., Schnick W., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2006, 632, 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blatov V. A., Shevchenko A. P., Prosperio D. M., Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 3576–3586. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shannon R. D., Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 1976, 32, 751–767. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sedlmaier S. J., Weber D., Schnick W., Z. Kristallogr. New Cryst. Struct. 2012, 227, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 28. López R., Gómez R., J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2012, 61, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tauc J., Grigorovici R., Vancu A., Phys. Status Solidi B 1966, 15, 627–637. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ermolaev V. L., Sveshnikova E. B., Russ. Chem. Rev. 1994, 63, 905–922. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kreidt E., Kruck C., Seitz M., Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2018, pp. 35–79. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Doffek C., Alzakhem N., Bischof C., Wahsner J., Güden-Silber T., Lügger J., Platas-Iglesias C., Seitz M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 16413–16423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.F. W. Karau, Dissertation, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (Germany) 2007.

- 34. Suhrmann R., Clusius K., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1926, 152, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stock A., Grüneberg H., Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1907, 40, 2573–2578. [Google Scholar]

- 36.H. Huppertz, Habilitationsschrift, Ludwig-Maximilians-UniversitätMünchen (Germany) 2003.

- 37.Agilent Technologies, CrysAlis Pro, Yarnton, Oxfordshire, England, 2011.

- 38.Bruker AXS, Inc., SADABS, Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 2001.

- 39. Wu G., Rodrigues B. L., Coppens P., J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2002, 35, 356–359. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sheldrick G. M., Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.A. A. Coelho, TOPAS-Academic, Version 6, Coelho Software, Brisbane (Australia), 2016.

- 42. Harris R. K., Becker E. D., Cabral de Menezes S. M., Granger P., Hoffman R. E., Zilm K. W., Pure Appl. Chem. 2008, 80, 59–84. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary