Summary

Pathogenic fungi often target the plant plasma membrane (PM) H+‐ATPase during infection. To identify pathogenic compounds targeting plant H+‐ATPases, we screened extracts from 10 Stemphylium species for their effect on H+‐ATPase activity.

We identified Stemphylium loti extracts as potential H+‐ATPase inhibitors, and through chemical separation and analysis, tenuazonic acid (TeA) as a potent H+‐ATPase inhibitor. By assaying ATP hydrolysis and H+ pumping, we confirmed TeA as a H+‐ATPase inhibitor both in vitro and in vivo. To visualize in planta inhibition of the H+‐ATPase, we treated pH‐sensing Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings with TeA and quantified apoplastic alkalization.

TeA affected both ATPase hydrolysis and H+ pumping, supporting a direct effect on the H+‐ATPase. We demonstrated apoplastic alkalization of A. thaliana seedlings after short‐term TeA treatment, indicating that TeA effectively inhibits plant PM H+‐ATPase in planta. TeA‐induced inhibition was highly dependent on the regulatory C‐terminal domain of the plant H+‐ATPase.

Stemphylium loti is a phytopathogenic fungus. Inhibiting the plant PM H+‐ATPase results in membrane potential depolarization and eventually necrosis. The corresponding fungal H+‐ATPase, PMA1, is less affected by TeA when comparing native preparations. Fungi are thus able to target an essential plant enzyme without causing self‐toxicity.

Keywords: fusicoccin, phytotoxin, plasma membrane H+‐ATPase, Stemphylium loti, tenuazonic acid

Introduction

Plants have evolved an advanced, multilayered defense system that fends off pathogen invasion. In response, pathogens have adapted by developing increasingly advanced invasion strategies to overcome plant defense mechanisms. Although plant defense relies on recognition of specific and conserved microbe structures, known as microbe‐associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), pathogens must target vital plant functions or the proteins involved (Jones & Dangl, 2006; Boller & Felix, 2009).

Many fungal species – both pathogenic and beneficial – target the plant plasma membrane (PM) H+‐ATPase (Elmore & Coaker, 2011). Nutrient uptake in plant cells is highly reliant on the electrochemical gradient across the PM, which is established primarily by the PM H+‐ATPase (Palmgren, 2001; Falhof et al., 2016). Protons are transported across the PM and energized by the hydrolysis of ATP into ADP and Pi. H+‐ATPase is essential for plant growth and development, as well as specific functions, such as stomata dynamics (Kinoshita & Shimazaki, 1999; Inoue & Kinoshita, 2017). The H+‐ATPase has 10 transmembrane helices, a large cytoplasmic domain, a C‐terminal autoinhibitory domain, and it belongs to the family of P‐type ATPases (Morth et al., 2011). The C‐terminus comprises approx. 100 amino acids and does not have any defined structure. Rather, it is suggested to wind around the body of the H+‐ATPase and physically constrain protein activity (Pedersen et al., 2007). H+‐ATPase regulation often involves direct phosphorylation of specific sites in the C‐terminus. The well‐studied Arabidopsis thaliana H+‐ATPase (AHA2) is activated by phosphorylation of Thr881 and Thr947, whereas it is inactivated by phosphorylation of Ser889 and Ser931 (Jahn et al., 1997; Fuglsang et al., 2007; Rudashevskaya et al., 2012; Guzel Deger et al., 2015; Haruta et al., 2015). Deletion of the regulatory C‐terminal domain or mutation of specific phosphorylation sites results in an activated pump that is insensitive to inhibition caused by phosphorylation.

Like plants, fungi are dependent on the PM H+‐ATPase to generate an electrochemical gradient across the PM. The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae H+‐ATPase (PMA1) shares structural similarity with its plant equivalent, but the C‐terminally regulatory domain is much shorter (Portillo, 2000; Pedersen et al., 2007). PMA1 has only two known phosphorylation sites, both of which are responsive to glucose (Mazón et al., 2015). This difference in regulatory mechanisms between the H+‐ATPases of plants and fungi creates the opportunity for fungal compounds to interact with plant H+‐ATPases without affecting the fungus itself. Indeed, the fungal phytotoxin fusicoccin (FC), from the fungus Fusicoccum amygdali, specifically stabilizes binding between the regulatory C‐terminal domain of the plant PM H+‐ATPase and its activating 14‐3‐3 protein, resulting in irreversible activation of the pump (Fuglsang et al., 1999, 2003; Würtele et al., 2003). FC is used widely to investigate H+‐ATPase activation in the laboratory; however, plants treated with FC lose control of stomata regulation and suffer from uncontrolled water loss and wilt (Marre, 1979).

Members of the fungal species Stemphylium are plant pathogens that cause leaf spots in crops such as asparagus (Asparagus officinalus), garlic (Allium sativum), parsley (Petroselinum crispum), pear (Pyrus communis) and sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) (Köhl et al., 2009; Koike et al., 2013; Hanse et al., 2015; Gálvez et al., 2016; Graf et al., 2016; Tanahashi et al., 2017). The taxonomy and metabolite production of Stemphylium spp. reveal a large family of both host‐specific and nonhost‐specific pathogenic fungi, producing a vast number of diverse metabolites (Woudenberg et al., 2017; Olsen et al., 2018). However, the invasion strategy and plant pathogenicity of Stemphylium spp. remain elusive.

In this study, we screened a range of chemical extracts from different plant pathogenic fungi and identified Tenuazonic acid (TeA) from S. loti as specifically targeting the plant PM H+‐ATPase. TeA previously was shown to inhibit photosynthesis, and the potential use of TeA as a herbicide targeting PSII was recently reviewed by Chen & Qiang (2017). Herein we show that TeA inhibits plant PM H+‐ATPases at micromolar concentrations by a mechanism involving the C‐terminal regulatory domain. Furthermore, we show that TeA targets the plant PM H+‐ATPase with a higher specificity compared to its S. cerevisiae homolog, PMA1, when comparing native preparations of H+‐ATPase. These results suggest that Stemphylium loti targets the PM H+‐ATPase of the host cell upon infection as part of a mechanism that eventually leads to cell death.

Materials and Methods

Chemical materials

Tenuazonic acid (TeA) (cat #610‐88‐8) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). Fusicoccin (FC) (cat #F0537) was purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich.

Purification of spinach plasma membranes

Plasma membrane (PM)‐enriched vesicles from Spinacia oleracea (baby spinach) were isolated using two‐phase partitioning as described by Lund & Fuglsang (2012). Fresh S. oleracea leaves (30 g) were homogenized in buffer (50 mM MOPS, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM Na4P2O7, 0.33 M sucrose and 1 mM Na2MoO4, pH 7.5) and centrifuged for 15 min at 10 000 g. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged for 30 min at 50 000 g, and the pellet was resuspended in 330/5 buffer (0.33 M sucrose and 5 mM K2HPO4). Following PM were enriched by two‐phase partitioning (in 20% Dextran T500 solution, 0.33 M sucrose, 5 mM K2HPO4 and 4 mM KCl). PM fractions were frozen in liquid N2 and stored at − 80°C.

In cases where plant material was pretreated, S. oleracea leaves were incubated with 5 μM TeA or an equal volume of 1% DMSO (control) for 15 min at room temperature before homogenization.

Plant material for bioimaging and growth tests

For perfusion assays, Arabidopsis thaliana (ecotype Col‐0) seeds stably expressing the pH sensor apo‐pHusion (Gjetting et al. 2012) were surface‐sterilized and grown under long‐day light conditions (16 h : 8 h, light : dark photoperiod) on agar plates containing ½ Murashige & Skoog (½MS) (Murashige & Skoog, 1962) + 1% (w/v) sucrose for 4–5 d before perfusion imaging experiments.

In order to test the effect of TeA on root growth, Arabidopsis thaliana (Col‐0) seeds were surface sterilized using 1–5% w/w sodium hypochlorite and 0.73% w/w HCl. Seeds were saturated over night at 4°C on ½MS including vitamins (1% sucrose, 0.7% plant agar). Germinated and grown for 6 d under long‐day light conditions (16 h : 8 h, light : dark, at 20°C) before transferring to ½MS agar containing 0, 2.5, 5, 10 or 20 μM TeA. Seedlings were grown for another 6 d, and growth were measured every second day. Image analysis was done using imagej v.1.47.

Perfusion assays

Roots of 4‐ to 5‐d‐old seedlings were immobilized with agar on Teflon‐coated slides, covered with a droplet of bath solution (0.1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM KCl and 10 µM MES, pH 5.5) and left to stabilize for 5–10 min before mounting on a Leica SP5‐X confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany). Using a ×20 dipping objective and a perfusion set‐up as described by Gjetting et al. (2012), either bath solution or 10 µM TeA was added.

Imaging data for apo‐pHusion fluorescence in the root elongation zone were acquired in xyt‐mode using a white light laser with line‐by‐line sequential scanning (line average 2) of the fluorescent proteins EGFP (excitation 488 nm; emission 500–530 nm) and mRFP1 (excitation 558 nm; emission 600–630 nm). The pinhole was set to an airy disc of 2.

Perfusion experiments showing no focal shift or unstable baseline before initial changing of buffer were selected for data analysis. Imaging data were analyzed using the open‐source software imagej (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/index.html). Background values were subtracted based on average intensity in areas without cells. Ratio calculations were created using pixel‐by‐pixel division of EGFP with mRFP1 generating floating 32‐bit images (RFP, red fluorescent protein). Regions of interest (ROIs) were chosen for calculating average pixel intensities to represent the largest possible area with cells in the same optical plane. Calibration curves were created using 10 mM MES/10 mM MOPS and 10 mM citrate. pH was adjusted to between 5 and 7 with KOH.

Yeast strain growth and plasmids

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain RS‐72 (MATa ade1‐100 his4‐519 leu2‐3, 112) was transformed with plasmids containing cDNA of the S. cerevisiae H+‐ATPase, PMA1 (pMP 400); AHA2 (pMP 1625); or C‐terminally truncated A. thaliana H+‐ATPases, aha2Δ40 (pMP 810), aha2∆77 (pMP210) or aha2Δ92 (pMP 132), under control of the PMA1 promoter (Regenberg et al., 1995). In the RS‐72 strain, the promoter of the endogenous PM H+‐ATPase PMA1 gene is replaced with a galactose‐dependent promoter, GAL1. When cells are grown on galactose, the endogenous H+‐ATPase PMA1 is expressed, whereas changing to glucose‐based media requires complementation with a functional PM H+‐ATPase. Transformed yeast cells were precultured in 5 ml of SGAH medium (galactose, yeast nitrogen base, adenine, histidine), transferred to 100 ml SGAH and cultured overnight. The cell culture was transferred to 500 ml sterile YPD medium for 20 h before membrane harvest. All cultures were grown at 30°C, 200 rpm.

Purification of yeast microsomes, plasma membranes and ER enriched membranes

Transformed Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells were harvested essentially as described by Villalba et al. (1992). To obtain PM and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) enriched fractions, microsomal fractions (MFs) were resuspended in GTED20 (20% glycerol (v/v), 100 mM Tris‐HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8, and 1 mM DTT) or STED10 (as GTED but with 10% sucrose w/v), placed on top of an 8‐ml sucrose step gradient consisting of increasing concentrations of sucrose in STED buffer (29%, 33%, 43% and 53% STED), and centrifuged for 16–20 h at 154 000 g at 4°C. PM fractions were collected at the 43/53% interface, ER fractions at the 29/33% interface, resuspended in ice‐cold MilliQ water, and centrifuged for 1 h at 250 000 g at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in GTED20, frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80°C.

Protein determination

Protein concentration was determined as described by Bradford (1976) with γ‐globulin as standard.

SDS‐PAGE and Western blotting

SDS‐gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) was performed according to standard techniques. SDS‐PAGE gels were stained using Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) to visualize separated proteins. For immunoblotting PM H+‐ATPase was detected by an antibody directed against the central part of AHA2. Phosphothreonine residues were detected by an anti‐P‐Thr antibody from Zymed (#71‐8200; dilution 1 : 600).

ATPase assay

H+‐ATPase activity was assayed according to the modified protocol of Baginski et al. (1967) described by Wielandt et al. (2015). For each well, 0.5–3 μg of protein was added in a 60 μl volume. For initial screening, the assay was performed at 30°C for 30 min, with 2.5 mM ATP, pH 7, in ATPase assay buffer (20 mM MOPS, 8 mM MgSO4, 50 mM KNO3 (inhibitor of V‐ATPases), 5 mM NaN3 (inhibitor of mitochondrial ATPases) and 0.25 mM Na2MoO4 (inhibitor of acid phosphatases)). For kinetics studies, an ATP regenerating system (5 mM phosphoenolpyruvate and 0.05 μg μl−1 pyruvate kinase) was added. For competition assays between TeA and FC/14‐3‐3, PM fractions were incubated with either 20 μM TeA and 1 μg 14‐3‐3 or 20 μM FC and 1μg 14‐3‐3 protein for 10 min at room temperature before assay initiation. PM from S. oleracea was used for control experiments and incubated with 10 µM FC, 1µg 14‐3‐3 protein or both for 10 min before assay start (total assay volume 60 µl). All ATPase assays were performed using three technical replicates and two biological replicates.

Proton pumping assay

Spinacia oleracea PM vesicles were turned inside out by the detergent Brij 58 (Johansson et al., 1995). Proton transport across the membrane was assayed using a modified version of the method described by Lund & Fuglsang (2012). The fluorescent probe 9‐amino‐6‐chloro‐2‐methoxyacridine (ACMA) can move freely across membranes in the unprotonated state. As inside‐out vesicles become loaded with H+ upon activation of the H+‐ATPase, ACMA becomes protonated and, thus, trapped inside vesicles, resulting in fluorescence quenching (excitation 412 nm; emission 480 nm). The assay was performed using 0.03 μg μl−1 protein in reaction buffer (11.4 mM MOPS, 56.8 mM K2SO4, 22.7 mM glycerol, 2.3 mM ATP, 1 μM ACMA, 0.05% Brij 58, and 60 nM valinomycin, pH 7.0) and started by addition of MgSO4 to a final concentration of 3 mM. The assay was stopped by addition of 10 μM of the H+ ionophore nigericin.

Dose–response and enzyme kinetics analysis

The dose–response kinetics of ATP hydrolysis of plant PM to inhibitors (i.e. fungal extracts and TeA) or agonists (i.e. FC/14‐3‐3) were determined by monitoring ATP hydrolysis in response to increasing inhibitor/agonist concentration. Kinetic data were obtained by monitoring ATP hydrolysis in response to increasing ATP concentration. All ATP hydrolysis data were obtained as described in the Materials and Methods ‘ATPase assay’ section. The concentration of inhibitor needed to reach half‐inhibition, IC50, was calculated by nonlinear regression fitted to log[inhibitor] vs the normalized response (variable slope, bottom constraint = 0.0) using prism 5.0a for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software; http://www.graphpad.com). The kinetic parameters V max and K m were estimated by nonlinear regression using prism 5.0a.

Statistics

All experiments were performed as technical triplicates (minimum) with two or more biological replicates. Values are presented as mean ± SEM; P‐values were calculated by one‐ or two‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post‐test analysis or Bonferroni post‐test using prism 5.0a. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Sequence alignment

The PMA1 amino acid sequence was obtained from the Saccharomyces Genome Database (http://www.yeastgenome.org). blastp was employed to identify sequences of H+‐ATPases from Stemphylium lycopersici, Alternaria alternata and Fusarium oxysporum with close similarity to that of PMA1 using the ExPASy Bioinformatics Resource Portal (http://www.expasy.org). blastp was employed to identify sequences of H+‐ATPases from Solanum lycopersicum, Brassica rapa and Glycine max with close similarity to AHA2 using ExPASy. Sequences were aligned using MUSCLE alignment software (Edgar, 2004), and pairwise distances were calculated using mega6 software (http://www.megasoftware.net). C‐terminal domains were predicted using tmhmm v.2.0 software (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0).

Fungal cultivation and fractionation

Several Stemphylium species were grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA), malt extract agar (MEA) and yeast extract with supplements (YES) plates for 10–14 d at 25°C in the dark. Fungal growth was then harvested and extracted with ethyl acetate containing 0.5% (v/v) formic acid. The extracts were concentrated in vacuo. Stemphylium loti FIP 217 was identified as the most active in the H+‐ATPase assay and was selected for further examination. A large‐scale extract from S. loti FIP 217 was generated by cultivation of S. loti FIP 217 on an equal number of PDA and YES plates (100 plates in total). Fungal growth was extracted with ethyl acetate containing 1% (v/v) formic acid, and the pooled extract was concentrated in vacuo.

The large‐scale S. loti FIP 217 extract initially was fractionated on diol‐functionalized silica (Biotage, Uppsala, Sweden) using an Isolera autoflasher (Biotage). The column was eluted stepwise using heptane, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate and methanol in 50% increments. The active fractions were pooled and taken through another round of fractionation using a C18 packed column. Fractions were eluted using a stepwise gradient of (A) H2O + 50 ppm trifluoroacetic acid and (B) methanol + 50 ppm trifluoroacetic acid, from 10% methanol to 100% methanol in increments of 10% methanol, using an Isolera autoflasher (Biotage), each fraction being three column volumes (45 ml).

UHPLC‐DAD‐HRMS

Extracts and fractions were analyzed by ultra high‐performance liquid chromatography‐diode array detection‐high‐resolution mass spectrometry (UHPLC‐DAD‐HRMS) using a 1290 Infinity UHPLC machine (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Separation was achieved on a 2.0 × 150‐mm Poroshell phenyl‐hexyl column (2.7 Å; Agilent). The column was eluted with a linear gradient consisting of (A) H2O + 20 mM formic acid and (B) acetonitrile + 20 mM formic acid starting at 10% B and increasing to 100% B over 15 min and held at this composition for 2 min before returning to initial conditions. MS detection was performed by a 6540 series quadropole time‐of‐flight (QTOF) mass spectrometer equipped with a dual jet stream electrospray ionization (ESI) source operating in positive mode. Data‐dependent auto MS/MS acquisition was performed using fixed collision induced dissociation (CID) collision energies of 10, 20 and 40 eV. The data generated were dereplicated employing an in‐house MS/HRMS natural product database (Kildgaard et al., 2014).

Results

Screening for inhibitors

We established a bioactivity‐based screening procedure to identify fungal compounds targeting the plant PM H+‐ATPase (Fig. 1). Crude extracts from 10 Stemphylium species (here named sp1–sp10) were initially tested for their effects on PM H+‐ATPase activity in vitro. All metabolites were extracted using ethyl acetate, dissolved in DMSO, and screened for effects on the activity of S. oleracea PM H+‐ATPase by quantifying ATP hydrolysis (Fig. 2). Most extracts had an inhibitory effect on H+‐ATPase activity, except sp8, which did not affect ATP hydrolysis. We chose the extract from sp7, S. loti, for further analysis.

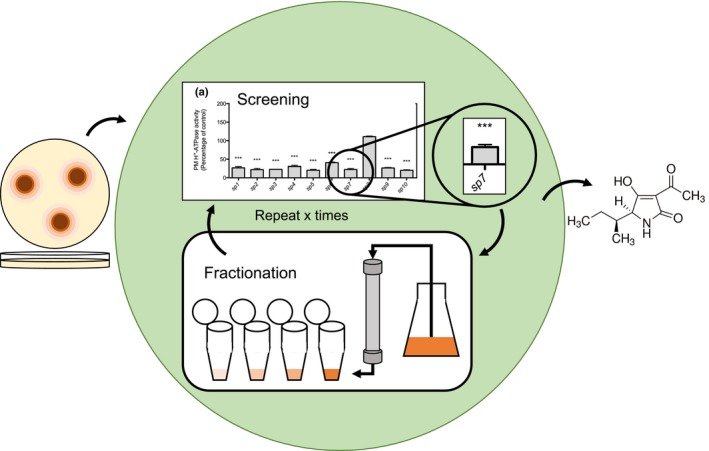

Figure 1.

Screening of fungal extracts for their effect on ATPase enzyme activity. Fungi were grown on plates, harvested and metabolites extracted. The extracts were added to plant H+ ‐ATPase assays in order to identify effectors of the plasma membrane (PM) H+‐ATPase. Fractions exhibiting a significant effect (***, P < 0.001) on the H+‐ATPase were further separated and re‐tested. This procedure was repeated until a relatively clean target was identified.

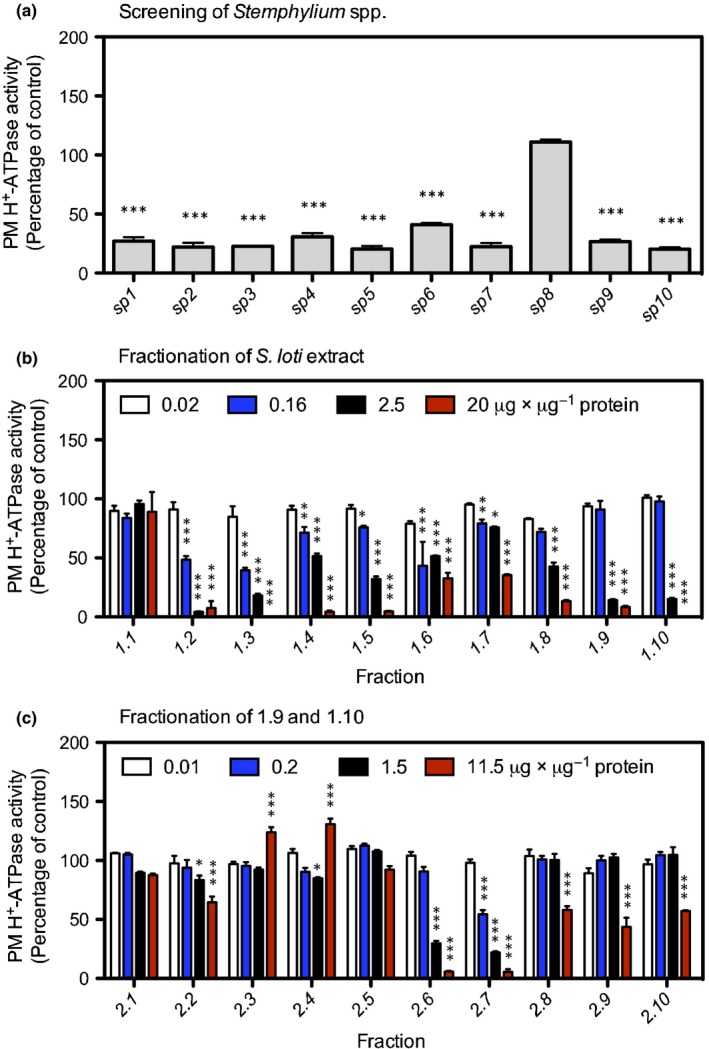

Figure 2.

H+‐ATPase activity of Spinacia oleracea plasma membranes in the presence of metabolites from Stemphylium spp. (a) Addition of total metabolites (30 µg) from 10 different Stemphylium spp., (b) Stemphylium loti extracts (from panel a) fractionated into 10 fractions (1.1–1.10), and (c) fractionation of fractions 1.9 and 1.10 (from panel b) into 10 new fractions, 2.1–2.10. Fractions 1.1–1.10 were added as 0.02 (white bars), 0.16 (blue bars), 2.5 (black bars) and 20 μg μg−1 protein (red bars). Fractions 2.1–2.10 were added as 0.01 (white bars), 0.2 (blue bars), 1.5 (black bars) and 11.5 μg μg−1 protein (red bars). Values are means ± SEM. Data were analyzed by two‐way ANOVA, and H+‐ATPase activity was compared to H+‐ATPase activity of the control (no addition of extracts, not shown) with a Bonferroni posttest. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; n = 3.

In order to identify the inhibitory compound(s), extracts of S. loti were further fractionated using normal‐phase (NP) and reversed‐phase liquid flash. The initial extract from Stemphylium loti was separated into 10 fractions (fractions 1.1–1.10), each of which was then tested individually (Fig. 2b). We used three different concentrations of extract to assess whether the inhibitory effect was dose‐dependent (Fig. 2b). Fractions 1.9 and 1.10 were the best candidates and were further tested for their dose‐dependency. These two fractions inhibited PM H+‐ATPase activity in a dose‐dependent manner with IC50 values of 0.82 and 0.64 µg µg−1 protein, respectively (Fig. 3a; Table 1). Fractions 1.9 and 1.10 were further fractionated into 10 fractions (2.1–2.10) by reversed‐phase HPLC. Again, we tested each fraction individually for its effect on ATP hydrolysis by the plant H+‐ATPase (Fig. 2c). The inhibitory molecules were clearly separated into fractions 2.6 and 2.7. The IC50 values were 0.77 and 0.33 µg µg−1 protein, respectively (Fig. 3b; Table 1).

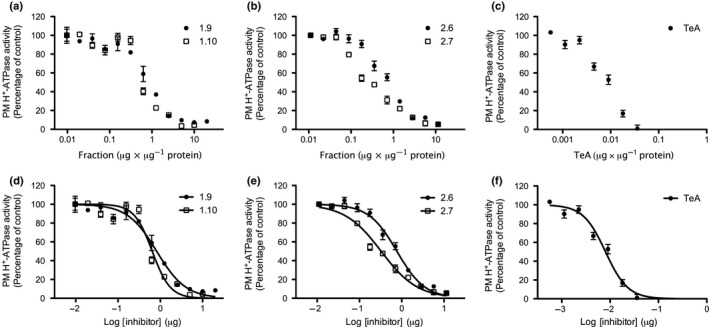

Figure 3.

Dose‐dependent inhibition of H+‐ATPase activity measured in Spinacia oleracea plasma membranes (PMs) in response to tenuazonic acid (TeA) treatment. Values are means ± SEM. Experiments with Stemphylium loti fractions 1.9 and 1.10 (a), and 2.6 and 2.7 (b) were carried out in triplicate (n = 3), whereas experiments with TeA (c) were carried out in triplicate and on three independent PM fractions (n = 9). (d, e, f) Data were analyzed using nonlinear regression and fitted to log[inhibitor] (µg) vs the normalized response for determination of IC50 values.

Table 1.

IC50 values of Stemphylium loti fractions 1.9, 1.10, 2.6 and 2.7 and tenuazonic acid (TeA) in ATP hydrolysis assays using Spinacia oleracea plasma membrane (PM) H+‐ATPases.

| Stemphylium loti extract | IC50 (µg µg−1 protein) | Ratio: IC50 of extract/IC50 of TeA |

|---|---|---|

| Fraction 1.9 | 0.82 (0.69–0.97) | 102.7 |

| Fraction 1.10 | 0.65 (0.55–0.76) | 80.7 |

| Fraction 2.6 | 0.77 (0.68–0.87) | 96.3 |

| Fraction 2.7 | 0.33 (0.28–0.38) | 40.9 |

| TeA (commercial) | 0.008 (0.007–0.009) | 1 |

ATP hydrolysis was analyzed using nonlinear regression and fitted to log[inhibitor] vs the normalized response to determine IC50 values. For S. oleracea PMs treated with fractions 1.9, 1.10, 2.6 and 2.7, n = 3. For S. oleracea PMs treated with TeA, n = 9.

We analyzed fractions 2.6 and 2.7 by HPLC‐DAD‐HRMS and dereplicated the data using a MS/HRMS library (Kildgaard et al., 2014). This revealed TeA to be a prevalent compound and possible candidate for PM H+‐ATPase inhibition. Commercially available TeA was purchased for further experiments. TeA inhibited PM H+‐ATPase‐mediated ATP hydrolysis with an IC50 value of 8 ng TeA µg−1 protein, equivalent to 0.7 µM under these assay conditions. This corresponds to a 103‐, 81‐, 96‐ and 41‐fold increase in inhibitory effect compared to fractions 1.9, 1.10, 2.6 and 2.7, respectively (Table 1).

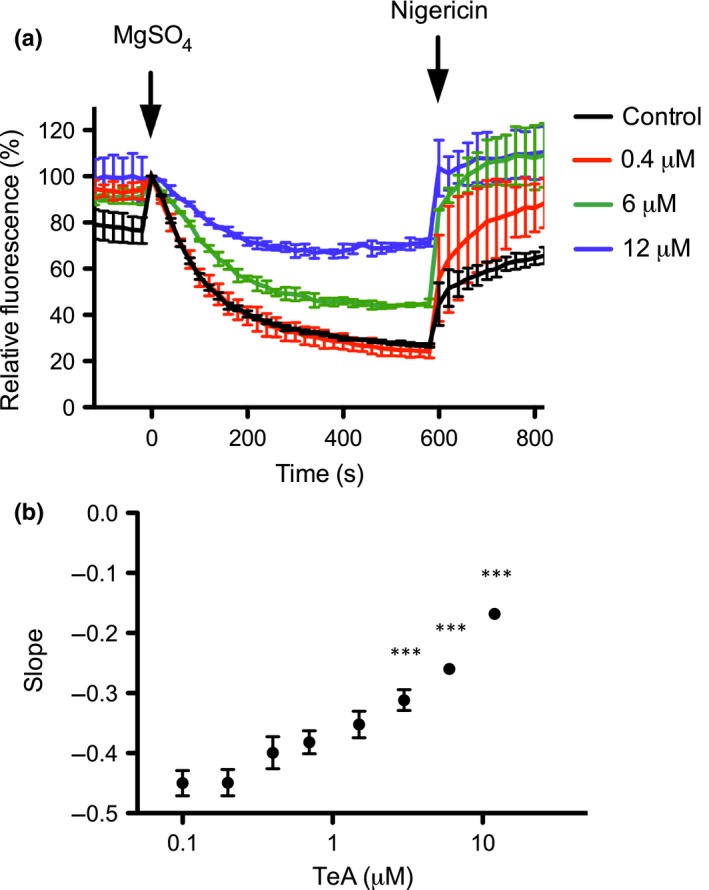

In order to confirm the inhibitory effect of TeA on the PM H+‐ATPase, we employed another assay measuring H+ pumping rate as opposed to the previously used assay measuring ATP hydrolysis. Accumulation of protons in inside‐out vesicles was measured using the fluorescent probe ACMA. Upon protonation, ACMA is trapped inside the vesicles, leading to a decrease in fluorescence. We treated inside‐out vesicles with TeA in the range of 0.1–12 µM (Fig. 4a). A clear reduction in fluorescence was observed upon TeA addition. The initial rate of proton transport into vesicles was estimated by linear regression of the decrease in fluorescence from time 0–120 s. The resulting slope was plotted as a function of TeA concentration (Fig. 4b). TeA concentrations of 3, 6 and 12 µM significantly inhibited proton pumping compared to the control. Taken together, these data indicate that TeA inhibits both ATP hydrolysis and proton pumping, confirming that TeA is an inhibitor of the plant PM H+‐ATPase in vitro.

Figure 4.

Tenuazonic acid (TeA) effect on H+ pumping of Spinacia oleracea plasma membrane (PM) vesicles. (a) Accumulation of protons in inside‐out PM vesicles of S. oleracea treated with increasing concentrations of TeA visualized and quantified using the fluorescent probe ACMA. Addition of MgSO4 initiates ATP‐stimulated proton pumping into vesicles, whereas addition of nigericin releases the trapped protons by acting as a proton ionophore. Values are means ± SEM based on two technical replicates (n = 2) and are representative of two independent PM purifications. (b) The initial slope of each curve (from t = 0 s to t = 120 s) was estimated by linear regression and plotted as a function of TeA concentration (µM). Values are means ± SEM based on two technical replicates and are representative of two independent PM fractions. Data were analyzed using one‐way ANOVA, and Dunnett's multiple comparisons test was used to calculate the difference in slopes compared to the control: ***, P < 0.001.

TeA mode of action

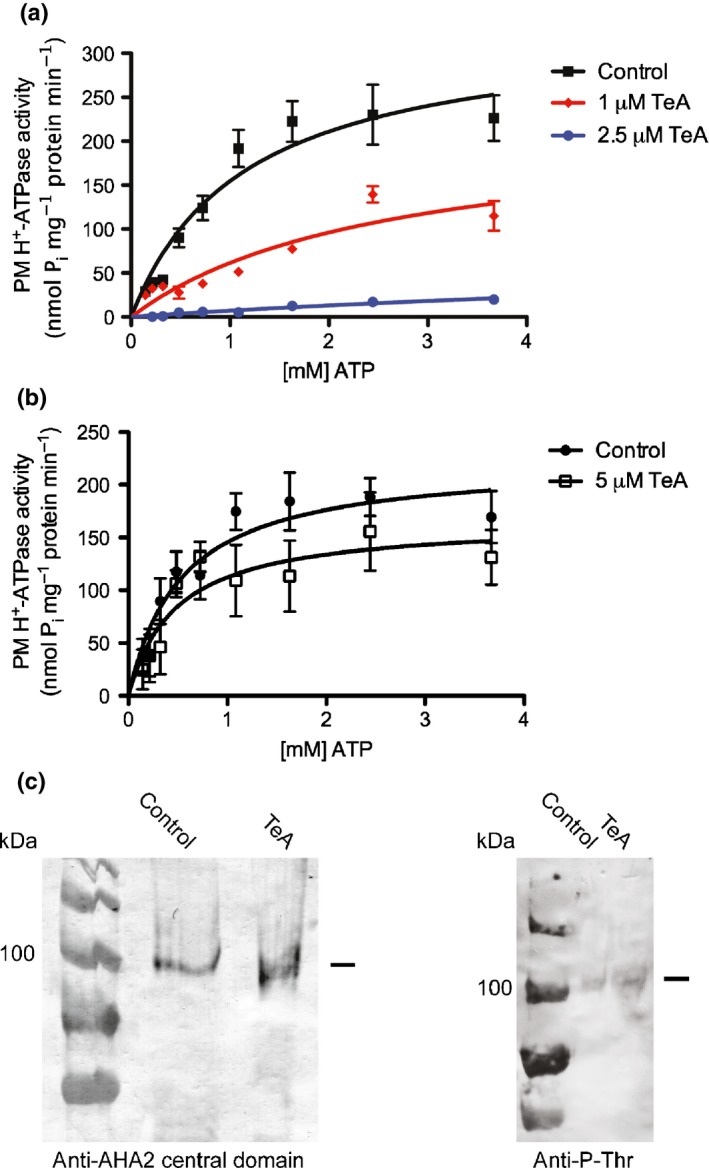

In order to characterize the mechanism of TeA inhibition, we investigated the effect of TeA on H+‐ATPase kinetics by combining increasing concentrations of the substrate, ATP, with different concentrations of TeA (Fig. 5a). A preliminary Hanes–Woolf plot revealed similar K m values independent of TeA, whereas V max was affected in the presence of both 1 and 2.5 µM TeA. The data were fitted as a noncompetitive inhibitor using nonlinear regression. This showed that V max decreased from 332.4 to 219.3 nmol Pi mg−1 protein min−1 and to 83.8 nmol Pi mg−1 protein min−1 after treatment with 1 and 2.5 µM TeA, respectively (Table 2). These results indicate that TeA inhibits H+‐ATPase activity by acting as a noncompetitive inhibitor of ATP.

Figure 5.

Kinetic analysis of Spinacia oleracea plasma membrane (PM) H+‐ATPase inhibition by tenuazonic acid (TeA). Specific activity was plotted as a function of ATP concentration (mM) at the indicated concentrations of TeA. (a) In vitro treatment. (b) In vivo treatment of S. oleracea leaves, 5 μM TeA or DMSO (control) for 15 min before purification of plasma membranes. Values are means ± SEM of four technical replicates of two independent PM samples (n = 8). (c) Immunodetection of PM H+‐ATPase and Phospho‐Threonine in the plasma membrane samples (20 µg per lane). +/− indicates pretreatment with TeA or not.

Table 2.

Effect of tenuazonic acid (TeA) on K m and V max of the Spinacia oleracea plasma membrane (PM) H+‐ATPase.

| Tenuazonic acid (μM) | K m (mM ATP) | V max (nmol Pi mg−1 min−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.15 (0.59–1.71) | 332.4 (262.9–401.8) |

| 1.0 | 2.56 (0.74–4.38) | 219.3 (132.5–306.1) |

| 2.5 | 10.96 (0.0–37.0) | 83.8 (−76.6–244.2) |

ATP hydrolysis of S. oleracea PM fractions was measured at different ATP concentrations in response to various TeA doses, and enzyme kinetic constants, K m and V max, were determined from nonlinear regression of the Michaelis–Menten equation. Values are means ± SEM of four technical replicates of two independent PM fractions (n = 8).

In order to further investigate the inhibitory effect of TeA on the H+‐ATPase, we treated S. oleracea leaves in vivo with 5 μM TeA, or DMSO as a control, for 15 min before purification of PMs. In vivo treatment with TeA did not affect K m, whereas V max was decreased in the subsequent ATPase activity test (Fig. 5b), thus confirming the data obtained from the in vitro treatment experiment (Table 3). As the observed decrease in V max could be due to degradation of H+‐ATPase, PM fractions were separated on an SDS gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and the H+‐ATPase detected by immunoblotting. The bands corresponding to the PM H+‐ATPase were detected at c.100 kDa. No degradation was observed in the TeA‐treated sample compared to the control (Fig. 5c). Also, no difference was observed between the two samples in the degree of Threonine phosphorylation. These results indicate that the observed decrease in V max is caused neiether by protein degradation nor by post‐translational modification of the Thr‐residue in the very C‐terminal end, but isntead by a TeA‐mediated inhibition of the H+‐ATPase.

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters, K m and V max, for Spinacia oleracea plasma membrane (PM) H+‐ATPases in response to tenuazonic acid (TeA) pretreatment.

| K m | V max | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.53 (0.21–0.86) | 223.1 (178.0–268.2) |

| TeA 5 μM | 0.48 (0.02–0.93) | 165.8 (115.1–216.5) |

ATP hydrolysis in S. oleracea PM fractions purified from leaves that had been pretreated with 5 μM TeA was measured at various ATP concentrations. The enzyme kinetic constants, K m and V max, were determined from nonlinear regression of the Michaelis–Menten equation. Values are means ± SEM of four technical replicates of two independent PM fractions (n = 8).

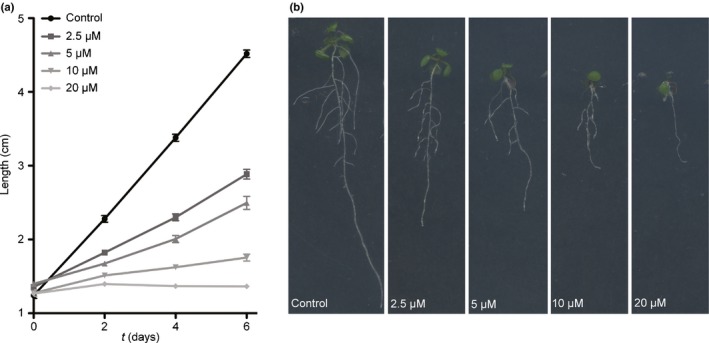

Effect of TeA on A. thaliana root growth

In order to investigate the effect of TeA on plant growth, a growth experiment was set up in which 6‐d‐old A. thaliana seedlings were moved to substrates containing 0–20 μM TeA for another 6 d of growth. TeA treatment resulted in reduced root growth on all concentrations, with 20 μM being the most effectful (Fig. 6a,b). Root growth was significantly different already at Day 2 on all concentrations employed (Fig. 6a). Seedlings treated with TeA exhibited fewer side roots and the abaxial side of leaves were purple due to stress, compared to controls (Fig. 6b). A close look at the epidermis revealed an increased number of root hairs at 5 µM TeA, but at 20 µM the cells in the elongation zone looked small and collapsed, compared to the normally elongated form of the cells.

Figure 6.

Tenuazonic acid (TeA) effect on Arabidopsis thaliana root growth. Seeds (Col‐0) were germinated and grown for 6 d on ½ Murashige & Skoog, before transfer to ½MS agar containing 0, 2.5, 5, 10 or 20 µM TeA, respectively, and further grown for 6 d. (a) Root length of 12‐d‐old seedlings was measured on days 0, 2, 4 and 6 after transfer to plates with TeA. Values given are means ± SEM, n = 32–48. Root lengths of treated plants were all highly significant (P < 0.001) for treatments compared to control after 2 d growth with TeA. (b) Images of 12‐d‐old seedlings.

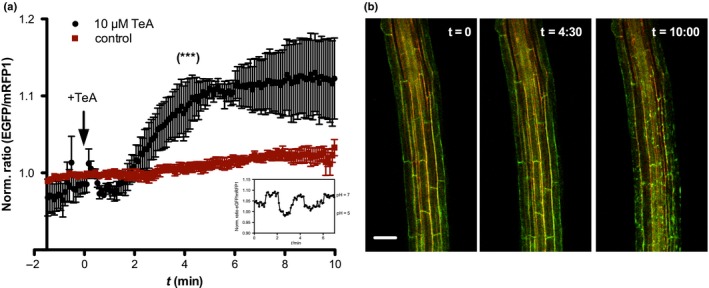

Live imaging of TeA effects on root cells

As the next step, we wanted to investigate the inhibitory effect of TeA on the cellular level. Seedlings expressing the ratiometric fluorescent pH biosensor apo‐pHusion, which is targeted to the apoplast (Gjetting et al., 2012), were used in a perfusion assay for live imaging of 4‐ to 5‐d‐old A. thaliana seedlings. Apoplastic pH was measured in elongating root cells as changes in the ratio of EGFP/mRFP1 intensity in response to treatment with either 10 µM TeA or bath solution (control). TeA treatment resulted in an apoplastic alkalinization starting after ~ 90 s of treatment, peaking after ~ 3–4 min, and lasting for the entire 10 min of the experiment (Fig. 7a). The apoplastic pH increased with 0.1 ratiometric unit indicating a pH change larger than 1 pH unit (see insert). In addition, root cells perfused with TeA appeared to accumulate fluorescent protein in fragmented endoplasmic reticulum compartments after ~ 5 min, and this accumulation increased in intensity over the course of the experiment (Fig. 7b; t = 10:00).

Figure 7.

In vivo tenuazonic acid (TeA)‐induced alkalization of the apoplast in elongating root cells of 4‐ to 5‐d‐old Arabidopsis thaliana roots expressing apo‐pHusion. (a) Seedlings were mounted with agar on a Teflon‐coated microscope slide and covered with a droplet of bath solution. Root cells in the elongation zone were viewed on an SP5‐X confocal laser scanning microscope, using a ×20 dipping objective and a perfusion setup for addition of TeA. After c. 2 min, 500 µl of 10 µM TeA (black curve) or bath solution (control, red curve) was added (black arrow) and the experiment was run for 10 min in total. Normalized ratio measurements of EGFP/mRFP1 are given as means ± SEM of n = 4 replicates. pH changes in response to TeA treatment were highly significant (***, P < 0.001) in comparison with controls (Student's t‐test). Inset shows in planta pH calibration curve using 10 mM MES, 10 mM MOPS, and 10 mM citrate buffer with pH adjusted to pH 5–7. (b) Confocal overlay images of EGFP (green) and mRFP1 (red) channels at three time points during the experiment: t = 0 before addition of TeA, t = 4:30 at the peak of the response, and t = 10:00 after 10 min. Bar, 50 µm.

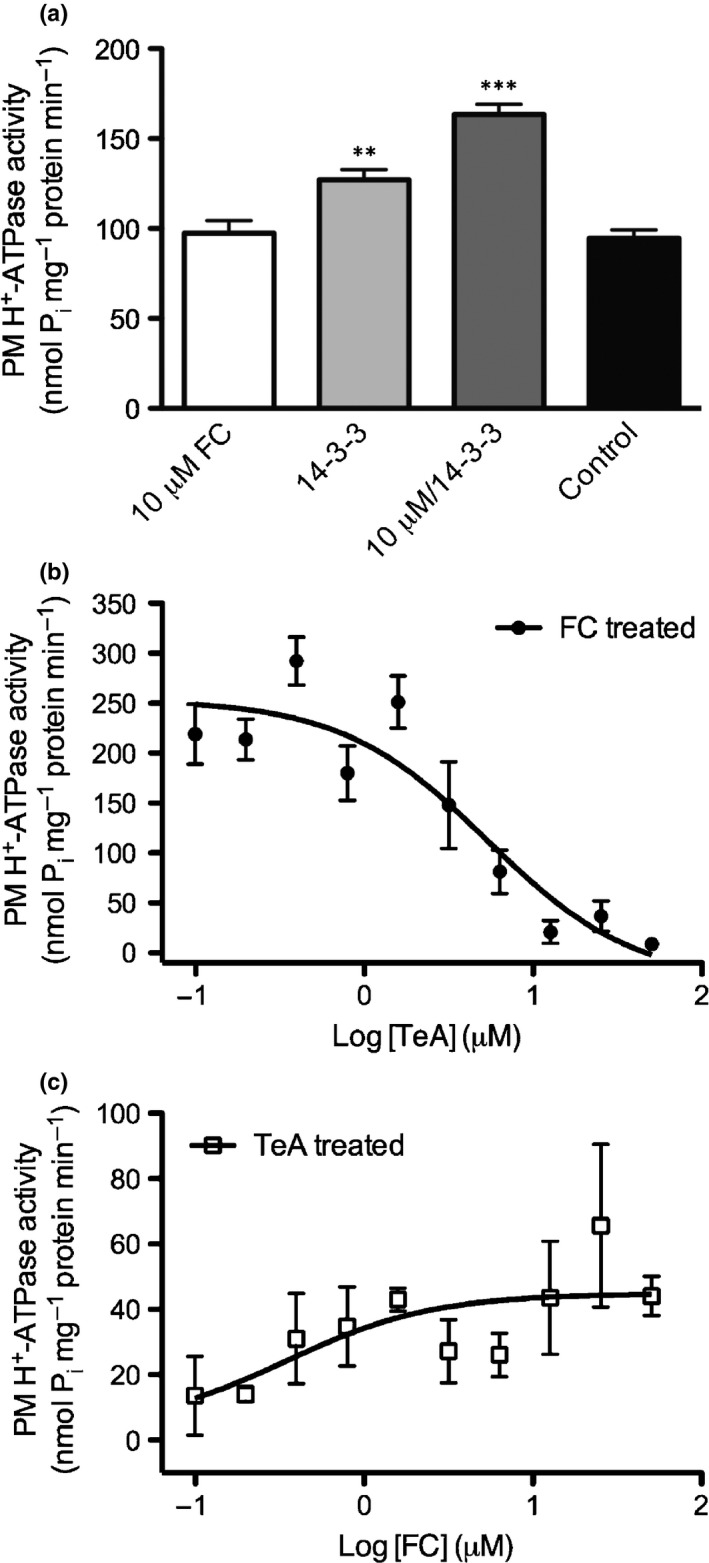

TeA treatment of plant material interferes with fusicoccin activation of PM H+‐ATPases

The fungal toxin FC is commonly used to study H+‐ATPase activation as it stabilizes binding of activating 14‐3‐3 protein to the C‐terminus of the plant H+‐ATPase. In vivo treatment with TeA suggests that H+‐ATPases inactivated by TeA are not degraded, but rather permanently inactivated. To investigate the mechanism of binding between TeA and the H+‐ATPase, we initially confirmed that FC and 14‐3‐3 together activate the PM H+‐ATPase (Fig. 8a). We then incubated PM fractions with 20 μM FC + 14‐3‐3 (1 µg) for 10 min and measured ATP hydrolysis at increasing TeA concentrations (Fig. 8b). A clear effect of TeA was observed, as TeA was able to reverse the activated conformation induced by FC. The data were analyzed using nonlinear regression, revealing an IC50 value of 5.4 μM, significantly higher than 0.7 as obtained in the original material.

Figure 8.

Competition between Fusicoccin (FC) and tenuazonic acid (TeA). (a) Activation of Spinacia oleracea plasma membrane (PM) H+‐ATPase preincubated with either FC, 14‐3‐3 or FC/14‐3‐3 before assay start. (b) Dose‐dependent TeA inhibition of S. oleracea PM H+‐ATPase preincubated with FC and 14‐3‐3 protein before assay start. (c) Dose‐dependent FC/14‐3‐3 activation of S. oleracea PM H+‐ATPase preincubated with 20 μM TeA before assay start. (b, c) Data were analyzed using nonlinear regression and fitted to log[agonist] (μM) vs the normalized response (variable slope) to determine the half maximal effective concentration (EC50) value. FC (10 µM) and 14‐3‐3 (1 µg) were used in all treatments. Treatments with 14‐3‐3 alone or FC/14‐3‐3 were significantly different from nontreated (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). Experiments were performed in triplicates of two independent PM fractions, and values represent means ± SEM (n = 6).

Similarly, we pre‐incubated PM fractions with 20 μM TeA and 14‐3‐3 protein for 10 min and measured ATP hydrolysis at increasing FC concentrations (Fig. 8c). Previous experiments suggested significant TeA‐induced inhibition of H+‐ATPase activity after 10 min of treatment, and without added FC, we observed little to no Pi in the ATP hydrolysis assay (10 nmol Pi mg−1 min−1). However, increasing the concentration of FC reduced the inhibition, although specific activity was very low compared to that in FC‐treated PM fractions in the absence of TeA (Fig. 8a–c).

Taken together, these results indicate that TeA effectively inhibits the plant PM H+‐ATPase even when the regulatory domain is displaced by association with 14‐3‐3 protein.

The plant PM H+‐ATPase regulatory C‐terminus is required for TeA inhibition

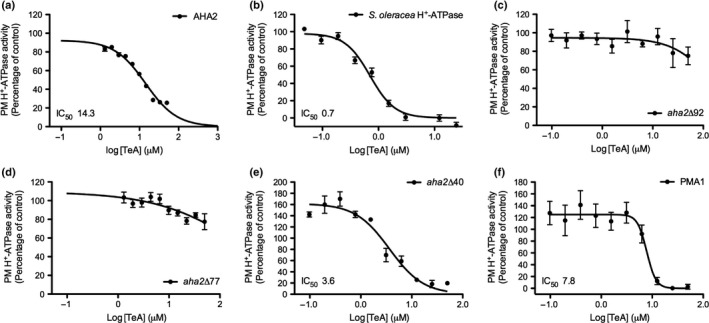

The TeA inhibition of the plant PM H+‐ATPase was dose‐dependent with an IC50 value of 8 ng (Fig. 3c,f), equivalent to 0.7 μM (Table 4; Fig. 8a). We previously demonstrated that TeA‐induced inhibition is noncompetitive with respect to ATP both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 5). The C‐terminus of plant H+‐ATPases is a well‐described autoregulatory domain, where both activation and inhibition are determined by phosphorylation of specific residues (Fuglsang et al., 2007), leading to binding of regulatory proteins (Fuglsang et al., 2003, 2007; Yang et al., 2010). Consequently, we sought to determine the importance of the C terminus in TeA‐induced inhibition of the H+‐ATPase. Wild‐type (WT) and C‐terminally truncated mutants of the well‐studied PM H+‐ATPase from Arabidopsis, AHA2, were heterologously expressed in S. cerevisiae. We purified membranes from S. cerevisiae containing aha2Δ92, aha2Δ77, aha2Δ40 and WT AHA2. All membranes were assayed for ATP hydrolysis in response to increasing TeA concentration (Fig. 9). TeA inhibited AHA2 activity (Fig. 9a) in a comparable manner to what we observed in plant‐derived material (Fig. 9b), but with a much higher IC50 value. By contrast, TeA was unable to inhibit ATP hydrolysis of recombinant aha2Δ92 expressed in S. cerevisiae (Table 4), even at concentrations of 50 µM TeA. The same tendency was observed for aha2Δ77, indicating that TeA inhibition is dependent on the presence of the regulatory C‐terminus. TeA inhibited both AHA2 and aha2Δ40, but with a much higher IC50 value (14.3 and 3.7 µM; Table 4) than observed in plant tissue. This could indicate that binding of TeA to the H+‐ATPase is sensitive to the protein conformation which might change due to the different lipid environment in the two organisms. Another interesting observation is that at low concentrations of TeA, a slight activation is observed for some of the H+‐ATPases (Fig 9e,f; aha2∆40 and PMA1).

Table 4.

IC50 values of tenuazonic acid (TeA) for Spinacia oleracea H+‐ATPase, Saccharomyces cerevisiae PMA1, and truncated Arabidopsis thaliana H+‐ATPases aha2Δ92 and aha2Δ40.

| IC50 (μM) | |

|---|---|

| Spinacia oleracea H+‐ATPase | 0.68 (0.59–0.78) |

| AHA2 (expressed in yeast) | 14.33 (12.0‐17.1) |

| PMA1 | 7.8 (5.8–10.4) |

| aha2Δ92 | ND |

| aha2Δ77 | ND |

| aha2Δ40 | 3.7 (2.7–5.0) |

ATP hydrolysis of plasma membrane (PM) fractions from S. oleracea and S. cerevisiae expressing PMA1, aha2Δ92, aha2Δ77 and aha2Δ40 or endoplasmic reticulum (ER) enriched fraction with AHA2, all treated with increasing concentrations of TeA. Data were analyzed using nonlinear regression and fitted to log[TeA] vs the response (variable to slope) (bottom constrain = 0.0) to determine the IC50 values. ND, not determined as data could not be fitted to the model.

Figure 9.

The effect of tenuazonic acid (TeA) on plasma membrane (PM) H+‐ATPases with C‐terminal deletions. TeA‐induced inhibition of H+‐ATPase activity measured on (a) AHA2 expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, (b) PMs from Spinacia oleracea, (c, d, e) C‐terminally truncated versions of AHA2; aha2Δ92 (c), aha2Δ77 (d) and aha2Δ40 (e), all expressed in S. cerevisiae, (f) endogenous S. cerevisiae H+‐ATPase PMA1. ATP hydrolytic activity experiments were performed in triplicates of three independent fractions (n = 9), except for AHA2 and aha2Δ77 (two independent fractions, n = 6). Values represent means ± SEM. Data were analyzed using nonlinear regression and fitted to log[TeA] vs the response (variable slope) (constrains bottom = 0.0) to determine the IC50 values.

The PM H+‐ATPase of S. cerevisiae, PMA1, and the plant PM H+‐ATPase are structurally comparable (Morth et al., 2011), although the C‐terminal regulatory domains are markedly different. The C‐termini of PMA1 and AHA2 were predicted to contain 43 and 111 amino acid residues, respectively. The PMA1 C‐terminal has two phosphorylation sites, Ser911 and Thr912 (Lecchi et al., 2007), whereas the C‐terminus of the A. thaliana H+‐ATPase, AHA2, has seven reported phosphorylation sites (Rudashevskaya et al., 2012), (Haruta & Constabel, 2003; Fuglsang et al., 2014). We purified PM fractions from S. cerevisiae expressing PMA1 and analyzed ATP hydrolysis at increasing TeA concentrations. TeA inhibition of PMA1 was in the same range as when AHA2/aha2∆40 was expressed in yeast. For PMA1, IC50 was found to be 7.8 µM TeA compared to 14.33 and 3.7µM for AHA2 and aha2∆40, respectively. Again this is higher than what is found in plant material (Fig. 9b,f; Table 4).

Taken together, these results indicate that TeA interacts with the regulatory C‐terminus of the plant H+‐ATPase to inhibit activity and that the length of the C‐terminus is important for this interaction. Furthermore, the data also indicate that the lipid composition of the membrane is of importance for the effect of TeA.

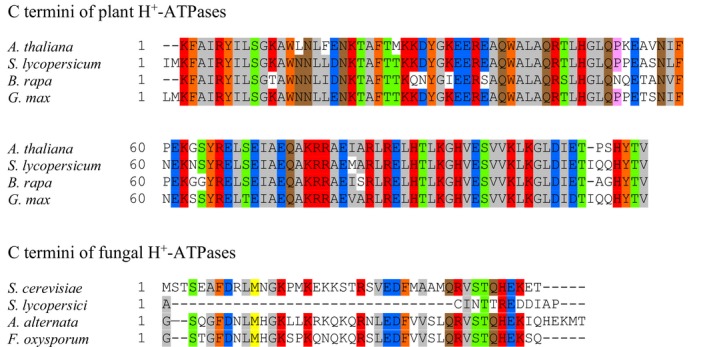

Sequence differences between H+‐ATPases from plants and fungi

The present data highlight the importance of the C‐terminus of the plant H+‐ATPase in TeA‐induced inhibition. We speculate that PMA1 is less sensitive to TeA because its regulatory domain differs from plants. We analyzed the amino acid sequence of AHA2 to identify highly similar sequences from S. lycopersicum, B. rapa and G. max for alignment. Likewise, we used the amino acid sequence of PMA1 to identify highly similar sequences from S. lycopersici, A. alternata and F. oxysporum for alignment (Fig 10). This revealed that the C‐termini of all plant H+‐ATPases are highly conserved, whereas the fungal C‐termini are less conserved. Besides the differences in length, few similarities were observed among fungal H+‐ATPases, and we expect that post‐translational regulation is essential for both plant and fungal H+‐ATPases.

Figure 10.

Alignments of amino acid sequences of the C termini of H+‐ATPases from the plants Arabidopsis thaliana, Solanum lycopersicum, Brassica rapa and Glycine max, and the fungi Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Stemphylium lycopersici, Alternaria alternata and Fusarium oxysporum. Numbers indicate length of the C terminus, and colors indicate conserved amino acids.

Pairwise distance, a measure of the number of substitutions per site between sequences, was calculated using Mega6 software to assess differences in amino acid composition between pairs of sequences. The pairwise distance between AHA2 and corresponding sequences from S. lycopersicum, B. rapa and G. max was 0.104, 0.118 and 0.121, respectively, confirming that very few amino acids differ between these sequences. Conservation of the regulatory domain in an essential enzyme highlights its importance in normal cell function, and we speculate that activity regulation through post‐translational modulation of the H+‐ATPase C‐termini is shared among the plants examined.

In order to test if TeA affects fungal growth, S. cerevisiae expressing either PMA1 or AHA2 were incubated with increasing concentrations of TeA and the growth was monitored for 48 h. No effect was found (data not shown). This result further confirms the limited ability of TeA to reach the fungal H+‐ATPase compared to the possibility of reaching the plant H+‐ATPase when inserted in native membranes.

Discussion

Stemphylium spp. invade numerous plant species, and cause leaf spots, ultimately leading to decreased yield and accumulation of mycotoxins in harvested crops (Hanse et al., 2015). In this study, we screened extracts from 10 different Stemphylium species for their effect on plant plasm membrane (PM) H+‐ATPase activity, to investigate whether this essential enzyme was targeted by any of the fungi. PM fractions were purified from Spinacia oleracea leaves using the aqueous two‐phase partitioning. Extracts from nearly all screened Stemphylium species inhibited ATP hydrolysis to various extents, suggesting that several species modulate host H+‐ATPase activity upon pathogen attack.

We further separated and screened the Stemphylium loti extract for its effect on ATP hydrolysis and identified tenuazonic acid (TeA) as the main compound responsible for H+‐ATPase inhibition (Fig. 3). TeA also inhibited proton pumping, confirming TeA as a plant H+‐ATPase inhibitor (Fig. 4). Identification of TeA in S. loti extracts contrasts with a recent publication by Olsen et al. (2018) claiming that S. loti does not produce TeA; however, revisiting their data revealed TeA to be a highly abundant component in all four extracts of S. loti screened (Olsen et al., 2018).

It is proposed that the main mechanism of TeA action in phytotoxicity is TeA blocking the electron transport chain of PSII (Chen et al., 2015, 2007, 2010). TeA inhibits the O2 evolution rate of PSII in isolated thylakoid membranes when treated with as little as 1 μM TeA; however, even 2 mM TeA is unable to inhibit O2 evolution completely (Chen et al., 2007), suggesting that the effect does not result from a high‐affinity interaction. Mesophyll cells in epidermal segments treated with 250 and 500 μM TeA for 30 min to 6 h show clear accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) leading to cell death after prolonged exposure (Chen et al., 2010). This requirement for long exposure and high concentrations contrasts with our results. We observed an effect on the plant PM H+‐ATPase after in vivo treatment with 5 μM TeA for 15 min and determined a concentration of inhibitor needed to reach half‐inhibition (IC50) of only 0.7 μM TeA in our ATP hydrolysis assay. Prolonged exposure to TeA will inhibit transfer of electrons from QA to QB; however, our present study suggests that an earlier response to TeA is the inhibition of the PM H+‐ATPase. Considering the low IC50 value of TeA on plant PM H+‐ATPases (0.7 µM), we expect that most H+‐ATPases will be effectively inhibited in plant tissue treated with 250 µM TeA. Effective inhibition of proton transfer across the PM leads to depolarization and eventually necrosis (Golstein & Kroemer, 2007). When one cell suffers from necrosis, cell debris will spread to neighboring cells causing increased ROS (Apel & Hirt, 2004). The ROS accumulation observed in response to TeA by Chen et al. (2010) may therefore be explained by necrosis due to severe membrane depolarization, rather than blocking of the electron transport chain.

A decrease in ATP hydrolysis and proton pumping could be caused by protein degradation, and TeA is reported to inhibit the release of newly synthesized proteins (Shigeura & Gordon, 1963). To rule out protein degradation as the cause for decreased H+‐ATPase activity, we pretreated leaves of S. oleracea with 5 μM TeA, for 15 min before PM purification. Immunoblotting analysis revealed that TeA pretreatment did not alter H+‐ATPase concentrations in PM fractions nor their phosphorylation status (Fig. 5c). We also investigated the effect of TeA on the kinetic constants V max and K m. Pretreatment of S. oleracea with TeA before PM purification resulted in a decrease in V max from 223.1 to 165.8 ng Pi mg−1 protein min−1 compared to the control. The ATP dose necessary to reach half of V max and K m remained largely unaffected, suggesting that TeA does not compete for the ATP‐binding site of the PM H+‐ATPase.

In order to visualize the effect of TeA on plant growth, the root length of A. thaliana seedlings grown on TeA was measured. The effect of TeA was apparent already on Day 2 of growth with TeA. After Day 6, root length of seedlings treated with 2.5 μM TeA was on average 1.6 cm shorter than nontreated seedlings. Treatment with 20 μM TeA resulted in little to no growth, with average growth 0.1 cm after 6 d. This suggests that TeA is a potent toxin, which can be used to inhibit plant growth.

In order to confirm that TeA is a H+‐ATPase inhibitor in planta, we employed a live‐imaging method using the apoplastic pH sensor apo‐pHusion (Gjetting et al., 2012). Apoplastic pH increased within 2–4 min after treatment with 10 µM TeA (Fig. 8). By calibrating the change in fluorescence to known pH values, we estimated the increase in apoplastic pH to be from ~ 5 to 7 after TeA treatment. Intracellular pH is c. pH 7 in healthy plant cells, indicating that TeA treatment effectively eliminates the electrical gradient across the PM. Apoplastic pH did not return to initial pH for the duration of these experiments, suggesting an irreversible inactivation of H+‐ATPases. TeA is therefore a potent inhibitor of H+‐ATPase in planta.

PM H+‐ATPase activation by 14‐3‐3 includes dislocation of the C‐terminal regulatory domain and is dependent on phosphorylation of the penultimate threonine residue (Fuglsang et al., 1999). The fungal toxin fusicoccin (FC) stabilizes complex formation between the C‐terminal domain and the 14‐3‐3 protein (Fuglsang et al., 2003; Würtele et al., 2003). By pretreating PM fractions for 10 min with FC and 14‐3‐3 protein, before TeA, we demonstrated that TeA can ‘overcome’ the stable binding complex between the C‐terminus, 14‐3‐3 and FC. The IC50 value of TeA on FC‐activated PM H+‐ATPase fractions was 5.4 μM. For untreated PM, the IC50 value of TeA was 0.7 μM, indicating that FC/14‐3‐3 protein treatment increased the amount of TeA required to reach half‐inhibition by 7.8‐fold. Conversely, FC/14‐3‐3 protein was not able to reciprocally reactivate PM fractions incubated with 20 μM TeA for 10 min before assay start. In the absence of FC and 14‐3‐3 protein, we observed a specific activity of 10.1 Pi mg−1 protein min−1, which was increased to 44.1 Pi mg−1 protein min−1 when treated with 50 μM FC and 14‐3‐3 protein (1 μg μl−1). This demonstrates that PM H+‐ATPases inhibited by TeA to only a small degree can be reactivated by FC/14‐3‐3 protein, although this requires an elevated dose. These data suggest that the regulatory domain is not only involved in FC binding, but also is important for TeA‐induced inhibition.

The A. thaliana H+‐ATPase, AHA2, is permanently activated by removal of 77 or 92 amino acid residues of the C‐terminal regulatory domain (Palmgren et al., 1990; Regenberg et al., 1995). Interestingly, we did not observe TeA‐mediated inhibition of aha2Δ92 or aha2Δ77, confirming the importance of the regulatory domain in TeA‐mediated H+‐ATPase inhibition. The H+‐ATPase native to Saccharomyces cerevisiae, PMA1, responded to TeA treatment but required a higher dosage compared to the H+‐ATPase protein purified from S. oleracea. Interestingly, expression and purification of AHA2 in S. cerevisiae led to an increase in the IC50 value, reaching a value comparable to the one found for PMA1. Similarly, activity of aha2Δ40, where only 40 C‐terminal amino acid residues were removed, was not affected by TeA to the same degree as the S. oleracea H+‐ATPase. This indicates that not only the C‐terminal, but also the chemical environment is important for TeA inhibition. When AHA2 is inserted into yeast membranes the accessibility of TeA seems to be significantly reduced. One can imagine that TeA binds to a site generated between the body of the protein and is stabilized by the C‐terminus. We have previously demonstrated that lysophospholipids can activate the plant PM H+‐ATPase, whereas they do not have any effects on the fungal Pm H+‐ATPase (Wielandt et al., 2015). Additionally this regulation involved the regulatory C‐terminal domain. The regulatory domains of PMA1 and aha2Δ40 are of comparable length but do not show any sequence similarity, which might explain the difference in observed IC50 values. Based on these data, we suggest that inhibition by TeA requires the full regulatory domain of the plant H+‐ATPase.

Aligning the C‐terminal regulatory domains from H+‐ATPases of the plants A. thaliana, Solanum lycopersicum, Brassica rapa and Glycine max confirmed the very high degree of conservation of the PM H+‐ATPase between the four species (Fig. 10). This allows phytotoxins to be functional against many host plant species by targeting the regulatory domain to modulate plant H+‐ATPase activity. Stemphylium species are reported to target many different plant species, and targeting this highly conserved domain provides an opportunity to cause necrosis in many plants using the same metabolite.

In order to further illustrate that S. loti can target plant H+‐ATPases without affecting the activity of the endogenous H+‐ATPase, we aligned the amino acid sequences of H+‐ATPases from four plant species with H+‐ATPase sequences from four fungi. The C‐termini of the plant PM H+‐ATPases were predicted to be 111–114 amino acids long, whereas the C‐termini from S. cerevisiae, S. lycopersici, Alternaria alternata and Fusarium oxysporum H+‐ATPases were predicted to contain only 13–46 amino acids.

In addition to the theory that the plant C‐terminus is important for the binding, also the conformational change between E1 to E2 might play a role for binding of TeA. The binding site might be more exposed in one conformation as compared to another. Here we can speculate that a compound only binds when the binding site is exposed, which could be when the protein is in the E2 formation.

In conclusion, the fungus S. loti produces the phytotoxin TeA that specifically targets the plant PM H+‐ATPase. We demonstrated through extensive biochemical evaluation and direct visualization using apo‐pHusion plants that TeA inhibits the plant PM H+‐ATPase. Inhibition of the PM H+‐ATPase results in depolarization of the membrane potential and eventually necrosis. The corresponding fungal H+‐ATPase, PMA1, is much less affected, and we propose that this is due to structural differences in the C‐terminal regulatory domains, but, just as importantly, also due to the different lipid composition of the plasma membrane of fungi compared to plants. By utilizing these differences, fungi are able to target an essential plant enzyme without causing self‐toxicity.

Author contributions

SAR and TIP carried out fungal growth and compound purification; PKB and JØI did biochemical screening; PKB and NWH carried out biochemical characterization of TeA; SKG carried out bioimaging of the TeA effect in planta; NWH assessed the TeA effect on plant growth; PKB performed sequence alignment; TOL and ATF conceived and coordinated the experiments; and PKB wrote the first draft of the manuscript with input from SAR, TOL and ATF.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lasse Kjellerup for kindly providing us with yeast microsomal fractions expressing PMA1. This work was supported by The Danish Council for Independent Research, Technology and Production Sciences (FTP) grant no. DFF–4184‐00548 COMBAT.

References

- Apel K, Hirt H. 2004. Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annual Review of Plant Biology 55: 373–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baginski ES, Foa PP, Zak B. 1967. Determination of phosphate: Study of labile organic phosphate interference. Clinica Chimica Acta 15: 155–158. [Google Scholar]

- Boller T, Felix G. 2009. A renaissance of elicitors: perception of microbe‐associated molecular patterns and danger signals by pattern‐recognition receptors. Annual Review of Plant Biology 60: 379–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein‐dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry 72: 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Kang Y, Zhang M, Wang X, Strasser RJ, Zhou B, Qiang S. 2015. Differential sensitivity to the potential bioherbicide tenuazonic acid probed by the JIP‐test based on fast chlorophyll fluorescence kinetics. Environmental and Experimental Botany 112: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Qiang S. 2017. Recent advances in tenuazonic acid as a potential herbicide. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology 143: 252–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Xu X, Dai X, Yang C, Qiang S. 2007. Identification of tenuazonic acid as a novel type of natural photosystem II inhibitor binding in QB‐site of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii . Biochimica et Biophysica Acta – Bioenergetics 1767: 306–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Yin C, Qiang S, Zhou F, Dai X. 2010. Chloroplastic oxidative burst induced by tenuazonic acid, a natural photosynthesis inhibitor, triggers cell necrosis in Eupatorium adenophorum Spreng . Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Bioenergetics 1797: 391–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research 32: 1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore JM, Coaker G. 2011. The role of the plasma membrane H+‐ATPase in plant‐microbe interactions. Molecular Plant 4: 416–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falhof J, Pedersen JT, Fuglsang AT, Palmgren M. 2016. Plasma membrane H+‐ATPase regulation in the center of plant physiology. Molecular Plant 9: 323–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuglsang AT, Borch J, Bych K, Jahn TP, Roepstorff P, Palmgren MG. 2003. The binding site for regulatory 14‐3‐3 protein in plant plasma membrane H+‐ATPase: Involvement of a region promoting phosphorylation‐independent interaction in addition to the phosphorylation‐dependent C‐terminal end. Journal of Biological Chemistry 278: 42266–42272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuglsang AT, Guo Y, Cuin TA, Qiu Q, Song C, Kristiansen KA, Bych K, Schulz A, Shabala S, Schumaker KS et al 2007. Arabidopsis protein kinase PKS5 inhibits the plasma membrane H+‐ATPase by preventing interaction with 14‐3‐3 protein. Plant Cell 19: 1617–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuglsang AT, Kristensen A, Cuin TA, Schulze WX, Persson J, Thuesen KH, Ytting CK, Oehlenschlaeger CB, Mahmood K, Sondergaard TE et al 2014. Receptor kinase‐mediated control of primary active proton pumping at the plasma membrane. The Plant Journal 80: 951–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuglsang AT, Visconti S, Drumm K, Jahn T, Stensballe A, Mattei B, Jensen ON, Aducci P, Palmgren MG. 1999. Binding of 14‐3‐3 protein to the plasma membrane H+‐ATPase AHA2 involves the three C‐terminal residues Tyr 946 ‐Thr‐Val and requires phosphorylation of Thr 947 *. Biochemistry 274: 36774–36780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gálvez L, Gil‐Serna J, García M, Iglesias C, Palmero D. 2016. Stemphylium leaf blight of garlic (Allium sativum) in Spain: taxonomy and in vitro fungicide response. Plant Pathology Journal 32: 388–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjetting KSK, Ytting CK, Schulz A, Fuglsang AT. 2012. Live imaging of intra‐and extracellular pH in plants using pHusion, a novel genetically encoded biosensor. Journal of Experimental Botany 63: 3207–3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golstein P, Kroemer G. 2007. Cell death by necrosis: towards a molecular definition. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 32: 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf S, Bohlen‐Janssen H, Miessner S, Wichura A, Stammler G. 2016. Differentiation of Stemphylium vesicarium from Stemphylium botryosum as causal agent of the purple spot disease on asparagus in Germany. European Journal of Plant Pathology 144: 411–418. [Google Scholar]

- Guzel Deger A, Scherzer S, Nuhkat M, Kedzierska J, Kollist H, Brosché M, Unyayar S, Boudsocq M, Hedrich R, Roelfsema MRG. 2015. Guard cell SLAC1‐type anion channels mediate flagellin‐induced stomatal closure. New Phytologist 208: 162–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanse B, Raaijmakers EEM, Schoone AHL, van Oorschot PMS. 2015. Stemphylium sp., the cause of yellow leaf spot disease in sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) in the Netherlands. European Journal of Plant Pathology 142: 319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Haruta M, Constabel CP. 2003. Rapid alkalinization factors in poplar cell cultures. Peptide isolation, cDNA cloning, and differential expression in leaves and methyl jasmonate treated cells. Plant Physiology 131: 814–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haruta M, Gray WM, Sussman MR. 2015. Regulation of the plasma membrane proton pump (H+‐ATPase) by phosphorylation. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 28: 68–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue S, Kinoshita T. 2017. Blue light regulation of stomatal opening and the plasma membrane H+‐ATPase. Plant Physiology 174: 531–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn T, Fuglsang AT, Olsson A, Brüntrup IM, Collinge DB, Volkmann D, Sommarin M, Palmgren MG, Larsson C. 1997. The 14‐3‐3 protein interacts directly with the C‐terminal region of the plant plasma membrane H+‐ATPase. Plant Cell 9: 1805–1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson F, Olbe M, Sommarin M, Larsson C. 1995. Brij 58, a polyoxyethylene acyl ether, creates membrane vesicles of uniform sidedness. A new tool to obtain inside‐out (cytoplasmic side‐out) plasma membrane vesicles. The Plant Journal 7: 165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JDG, Dangl JL. 2006. The plant immune system. Nature 444: 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kildgaard S, Mansson M, Dosen I, Klitgaard A, Frisvad JC, Larsen TO, Nielsen KF. 2014. Accurate dereplication of bioactive secondary metabolites from marine‐derived fungi by UHPLC‐DAD‐QTOFMS and a MS/HRMS library. Marine Drugs 12: 3681–3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Shimazaki KI. 1999. Blue light activates the plasma membrane H+‐ATPase by phosphorylation of the C‐terminus in stomatal guard cells. EMBO Journal 18: 5548–5558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhl J, Groenenboom‐De Haas B, Goossen‐Van De Geijn H, Speksnijder A, Kastelein P, De Hoog S, Gerrits Van Den Ende B. 2009. Pathogenicity of Stemphylium vesicarium from different hosts causing brown spot in pear. European Journal of Plant Pathology 124: 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Koike ST, O'Neill N, Wolf J, Van Berkum P, Daugovish O. 2013. Stemphylium leaf spot of Parsley in California caused by Stemphylium vesicarium . Plant Disease 97: 315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecchi S, Nelson CJ, Allen KE, Swaney DL, Thompson KL, Coon JJ, Sussman MR, Slayman CW. 2007. Tandem phosphorylation of Ser‐911 and Thr‐912 at the C terminus of yeast plasma membrane H+‐ATPase glucose leads to ‐dependent activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 282: 35471–35481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund A, Fuglsang AT. 2012. Purification of plant plasma membranes by two‐phase partitioning and measurement of H+ pumping In: Shabala S, Cuin TA, eds. Plant salt tolerance: methods and protocols. Totowa, NJ, USA: Humana Press, 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marre E. 1979. Fusicoccin: a tool in plant physiology. Annual Review of Plant Physiology 30: 273–288. [Google Scholar]

- Mazón MJ, Mazón M, Eraso P, Portillo F. 2015. Specific phosphoantibodies reveal two phosphorylation sites in yeast Pma1 in response to glucose. FEMS Yeast Research 15: 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morth JP, Pedersen BP, Buch‐Pedersen MJ, Andersen JP, Vilsen B, Palmgren MG, Nissen P. 2011. A structural overview of the plasma membrane Na+, K+‐ATPase and H+‐ATPase ion pumps. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 12: 60–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. 1962. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia Plantarum 15: 473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen KJK, Rossman A, Andersen B. 2018. Metabolite production by species of Stemphylium . Fungal Biology 122: 172–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmgren MG. 2001. Plant plasma membrane H+‐ATPases. Evolution 52: 817–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmgren MG, Larsson C, Sommarin M. 1990. Proteolytic activation of the plant plasma membrane H+‐ATPase by removal of a terminal segment. Journal of Biological Chemistry 265: 13423–13426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen BP, Buch‐Pedersen MJ, Morth JP, Palmgren MG, Nissen P. 2007. Crystal structure of the plasma membrane proton pump. Nature 450: 1111–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portillo F. 2000. Regulation of plasma membrane H+‐ATPase in fungi and plants. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Reviews on Biomembranes 1469: 31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regenberg B, Villalba JM, Lanfermeijer FC, Palmgren MG. 1995. C‐terminal deletion analysis of plant plasma membrane H+‐ATPase: yeast as a model system for solute transport across the plant plasma membrane. Plant Cell 7: 1655–1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudashevskaya EL, Ye J, Jensen ON, Fuglsang AT, Palmgren MG. 2012. Phosphosite mapping of P‐type plasma membrane H+‐ATPase in homologous and heterologous environments. Journal of Biological Chemistry 287: 4904–4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigeura HT, Gordon CN. 1963. The biological activity of tenuazonic acid. Biochemistry 2: 1132–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanahashi M, Okuda S, Miyazaki E, Parada RY, Ishihara A, Otani H, Osaki‐Oka K. 2017. Production of host‐selective SV‐toxins by Stemphylium sp. Causing brown spot of European pear in Japan. Journal of Phytopathology 165: 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Villalba JM, Palmgren MG, Berberian GE, Ferguson C, Serrano R. 1992. Functional expression of plant plasma membrane H+‐ATPase in yeast endoplasmic reticulum. Journal of Biological Chemistry 267: 12341–12349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wielandt AG, Pedersen JT, Falhof J, Kemmer GC, Lund A, Ekberg K, Fuglsang AT, Pomorski TG, Buch‐Pedersen MJ, Palmgren M. 2015. Specific activation of the plant P‐type plasma membrane H+‐ATPase by lysophospholipids depends on the autoinhibitory N‐ and C‐terminal domains. Journal of Biological Chemistry 290: 16281–16291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woudenberg JHC, Hanse B, van Leeuwen GCM, Groenewald JZ, Crous PW. 2017. Stemphylium revisited. Studies in Mycology 87: 77–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Würtele M, Jelich‐Ottmann C, Wittinghofer A, Oecking C. 2003. Structural view of a fungal toxin acting on a 14‐3‐3 regulatory complex. EMBO Journal 22: 987–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Qin Y, Xie C, Zhao F, Zhao J, Liu D, Chen S, Fuglsang AT, Palmgren MG, Schumaker KS et al 2010. The Arabidopsis Chaperone J3 regulates the plasma membrane H+ ‐ATPase through Interaction with the PKS5 kinase. Plant Cell 22: 1313–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]