Abstract

Human exposures to fentanyl analogs, which significantly contribute to the ongoing U.S. opioid overdose epidemic, can be confirmed through the analysis of clinical samples. Our laboratory has developed and evaluated a qualitative approach coupling liquid chromatography and quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (LC-QTOF) to address novel fentanyl analogs and related compounds using untargeted, data-dependent acquisition. Compound identification was accomplished by searching against a locally-established mass spectral library of 174 fentanyl analogs and metabolites. Currently, our library can identify 150 fentanyl-related compounds from the Fentanyl Analog Screening (FAS) Kit), plus an additional 25 fentanyl-related compounds from individual purchases. Plasma and urine samples fortified with fentanyl-related compounds were assessed to confirm the capabilities and intended use of this LC-QTOF method. For fentanyl, 8 fentanyl-related compounds and naloxone, lower reportable limits (LRL100), defined as the lowest concentration with 100% true positive rate (n=12) within clinical samples, were evaluated and range from 0.5 ng/mL to 5.0 ng/mL for urine and 0.25 ng/mL to 2.5 ng/mL in plasma. The application of this high resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) method enables the real-time detection of known and emerging synthetic opioids present in clinical samples.

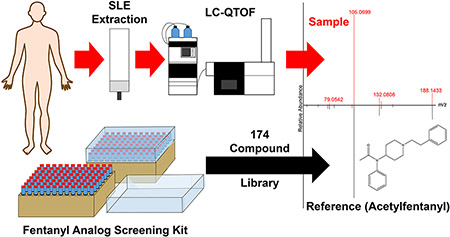

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Drug overdose deaths in the United States have risen substantially with deaths involving opioids contributing significantly to the drug overdose epidemic (Scholl et al., 2019). Much of this is due to synthetic opioids such as fentanyl and fentanyl analogs, with a 45.2% increase in death rates related to these compounds from 2016 to 2017 (Scholl et al., 2019). A similar trend has also been seen in Europe (UNODC, 2017; Mounteney et al., 2015). While fentanyl was synthesized in the 1960’s by Jansson pharmaceuticals, modifications to increase potency or onset has added multiple analogs to this family of compounds (Vardanyan and Hruby, 2014). In 2018, 8 out of the 26 synthetic opioids identified in the US were reported for the first time (DEA, 2018). With this rapid addition of new analogs, methods to identify exposure to as many fentanyl analogs as possible are needed.

Developed methods to detect fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and metabolites in biological matrices include immunoassays (Angelini et al., 2019; Guerrieri et al., 2019; Ruangyuttikam et al., 1990; Schuttler and White, 1984; Wang et al., 2011), gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (Buchalter et al., 2019; Gillespie et al., 1981; Misailidi et al., 2019; Van Rooy, 1981), and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (Fogarty et al., 2018; Seymour et al., 2019; Sofalvi et al., 2017; Strayer et al., 2018). While immunoassays are typically quick and sensitive, many are neither able to identify nor distinguish between emerging fentanyl analogs since the selectivity of the antibodies used was developed primarily for the detection of fentanyl (Guerrieri et al., 2019). When responses are detected, cross-reactivity of the antibodies may make it impossible to differentiate analogs (Guerrieri et al., 2019). Methods using GC-MS and LC-MS/MS have been developed for many fentanyl analogs in human matrices including urine, blood, plasma, and oral fluid (Buchalter et al., 2019; Busardo et al., 2019; Fogarty et al., 2018; Misailidi et al., 2019; Palamar et al., 2019; Salomone et al., 2019; Seymour et al., 2019; Sofalvi et al., 2017; Strayer et al., 2018). These methods were reported to have detection limits as low as 0.002 ng/mL for selected compounds, with most fentanyl analog detection limits around 0.1 ng/mL (Busardo et al., 2019; Fogarty et al., 2018; Misailidi et al., 2019; Salomone et al., 2019; Seymour et al., 2019; Sofalvi et al., 2017; Strayer et al., 2018). When applied to case reports of opioid overdoses, carfentanil, acetylfentanyl, acrylfentanyl, and furanyl fentanyl were detected at 0.0102 ng/mL to 827 ng/mL (Butler et al., 2018; Martucci et al., 2018; Mochizuki et al., 2018; Shanks and Behonick, 2017; Sofalvi et al., 2017; Swanson et al., 2017). The lowest concentration was attributed to carfentanil, which has also been determined to be significantly more toxic than most other analogs (Shanks and Behonick, 2017). The majority of these case studies identified in overdose samples were detected at 0.1 ng/mL or greater.

While targeted GC-MS and LC-MS/MS methods allow for low detection levels, they are limited to the analytes predetermined in each method. Recent targeted methods, developed in response to the opioid crisis, have typically reported around 20 fentanyl analogs per method (Busardo et al., 2019; Fogarty et al., 2018; Strayer et al., 2018). To identify a broader array of compounds, an untargeted approach for data collection is needed. High resolution mass spectrometry has been used as a data-independent technique for detection of multiple fentanyl analogs in clinical and forensic samples (Noble et al., 2018; Palmquist and Swortwood, 2019). Following data acquisition, the collected data are evaluated against a reference spectral library for accurate mass and fragmentation patterns to identify and confirm the compounds present. As new reference materials for emerging opioids becomes available their reference spectra can be added to the library. Since compounds are identified after data collection, the results can potentially be retrospectively and independently interrogated evaluated for these new compounds (Campos-Mañas et al., 2019; Noble et al., 2018; Partridge et al., 2018).

Mass spectral libraries can be purchased or created in-house. Currently commercially available forensic libraries offered by three major instrument vendors contain up to 18 fentanyl analogs. Published libraries include up to 50 fentanyl analogs; however, some of those identifications are based on predicted product ions, not the infusion of reference materials (Noble et al., 2018). Our method utilizes the newly available product line of Traceable Opioid Material§ Kits (TOM Kits§), specifically the Fentanyl Analog Screening (FAS) Kit, along with 25 other commercially available and custom synthesized compounds to create an in-house spectral library of 174 synthetic opioid compounds. Using Scientific Working Group for Forensic Toxicology (SWGTOX) guidelines, a qualitative method was developed and fully validated for a subset of 10 synthetic opioid compounds; including investigating the lower reportable limit, matrix effects, and possible interferences; in both urine and plasma (Scientific Working Group for Forensic, 2013). This method has been designed to collect data permitting the identification of currently known fentanyl-related compounds and retrospective data mining as new fentanyl analogs are discovered.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials.

High-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade methanol (Fisher, Hampton, NH), acetonitrile (The Lab Depot, Dawsonville, GA), and dichloromethane (DCM) (The Lab Depot, Dawsonville, GA) were used for all experiments. Deionized (DI) water was prepared with an on-site water purification system (Aqua Solutions Inc., Jasper, GA). Ammonium formate and formic acid (99%) were acquired from Sigma Aldrich (Pittsburg, PA). Isotopically labeled (2H5) standards of cyclopropylfentanyl, 2-furanylfentanyl, acrylfentanyl, isobutyrylfentanyl, ocfentanil, and methoxyacetylfentanyl were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Fentanyl, norfentanyl, and corresponding 2H5 labeled standards as well as acetylfentanyl and corresponding 13C6 labeled standard were purchased from Cerilliant (Round Rock, TX). Naloxone, naltrexone, heroin, 6-MAM, morphine, morphine-6-G, cocaine, and norcocaine were also purchased from Cerilliant. Norlofentanil and corresponding 2H3 labeled standard were purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, Canada). Carfentanil, norcarfentanil, sufentanil, norsufentanil, corresponding 2H5 labeled standards, and 13C6-alfentanil were custom synthesized by Battelle (Columbus, OH). Pooled urine and pooled plasma along with individual urine and plasma reference samples were purchased from Tennessee Blood Services (Memphis, TN). This study does not meet the definition of human subjects as specified in 45 CFR 46.102 (f) as all urine and plasma samples were acquired from commercial sources with appropriate institutional review board approvals.

2.2. Evaluation Samples.

Three novel opioids and benzodiazapines (NOB) survey samples from the College of American Pathologists (CAP) were used to challenge our method. The samples, prepared by CAP in processed ovine blood, were evaluated in the same manner as human plasma samples used for method development.

2.3. Fentanyl Analog Screening (FAS) Kit.

CDC has contracted Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI) to manufacture and distribute the FAS Kit containing 200 micrograms each of 120 fentanyl analogs and metabolites analytical reference materials (Fentanyl Analog Screening Kit, FAS Kit). In addition, an expansion pack (Emergent Panel Version 1, FAS V1) was developed to contain 200 micrograms of an additional 30 synthetic opioid related compounds. Each compound in the FAS Kit and FAS V1 was provided in separate, individual vials. A list of all synthetic opioids and related compounds in the FAS Kit and FAS V1 can be found on the vendor’s website (https://www.caymanchem.com/forensics/faskit/). FAS kit development is explored in greater depth by Mojica et al. (Mojica et al, 2019)

2.4. Working Solutions

Individual stock solutions of all analytes, purchased individually or provided in the FAS Kit and FAS V1, were prepared at 10 μg/mL in a mixture of methanol and DI water at a ratio of 3:2, respectively, with individual working solutions generated by diluting to 100 ng/mL in DI water. A 25 ng/mL internal standard (IS) working solution was created by a mixture of the isotopically labeled standards of fentanyl, carfentanil, acetylfentanyl, 2-furanylfentanyl, cyclopropylfentanyl, acrylfentanyl, sufentanil, ocfentanil, and methoxyacetylfentanyl. To form a 1 μg/mL quality control (QC) stock solution, 4-ANPP, acetylfentanyl, carfentanil, cyclopropylfentanyl, fentanyl, fluoroisobutyrylfentanyl, furanylfentanyl, methoxyacetylfentanyl, naloxone, and norfentanyl were diluted from the 10 μg/mL stock solutions. The QC stock solution was further diluted in pooled urine and plasma to create a positive QC Low (QCL) at 2 ng/mL and a positive QC High (QCH) at 15 ng/mL. In addition, an aliquot of pooled urine and plasma with no fortification was designated as a negative QC Blank (QCB).

2.5. Sample Preparation.

A 200 μL aliquot of urine or plasma sample was pipetted into a 2 mL conical bottomed 96-deep well plate. IS working solution (25 μL) was added to the 96-deep well plate, followed by 175 μL of 0.1% v/v formic acid in DI water. The 96-deep well plate was sealed with adhesive foil and mixed at 1,000 rpm for 5 minutes (Eppendorf MixMate, Hauppauge, NY). The extraction was automated using a Biotage Extrahera (Charlotte, NC). The diluted sample was pipetted onto a Biotage ISOLUTE SLE+ 400 μL plate and given a 5 second burst of positive pressure air. The sample was allowed to absorb onto the media for 5 minutes, after which time 900 μL of DCM was applied to each sample well in the SLE plate. The DCM eluted without added pressure for 5 minutes into an empty 96-deep well plate. After 5 minutes, 0.7 bar of positive pressure was applied to the SLE plate to ensure the entire aliquot of DCM had eluted before a second 900 μL aliquot of DCM was added again to each sample well in the SLE plate. After 5 minutes had elapsed after the addition of the second 900 μL aliquot, a final 5 second burst of positive pressure was applied to the SLE plate. The collection plate was removed from the Extrahera and dried down with N2 using a Porvair TurboVap (Ashland, VA) at a maximum temperature of 55 °C until dryness. The dried samples were then reconstituted in 100 μL of 78:22 10 mM ammonium formate in water : 0.1% v/v formic acid in acetonitrile. The 96-deep well plate was sealed with adhesive foil and shaken at 1,000 rpm for 5 minutes. The samples were then transferred into a 96-well PCR plate, heat sealed, and loaded into the instrument for analysis.

2.6. Liquid Chromatography.

An Agilent Technologies 1290 Infinity II Liquid Chromatography (LC) system (Santa Clara, CA) with a 100 × 3.0 mm Phenomenex (Torrance, CA) biphenyl column kept at 50 °C was used for chromatographic separation. The column has a particle size of 2.6 μm and a pore size of 100 Å. For separation the eluents (A) 10 mM ammonium formate in DI water and (B) acetonitrile containing 0.1% v/v formic acid were used in the following gradient with a 700 μL/min flow rate: 78% A held for 0.5 min then reduced to 75% A over next 8.5 min. After 9 min A reduced to 70% over 2 min, then dropped to 60% at 11.01 min. From 11.01 min A was reduced to 55% over 1.99 min, and at 13 min A reduced to 5% over 0.60 min, at which it was held until chromatography completion at 16 min. The sample (15 μL) was injected, and the needle multi-washed with methanol containing 1% v/v formic acid and 82:18 10 mM ammonium formate in DI water : 0.1% v/v formic acid in acetonitrile before each injection.

2.7. Mass Spectrometry.

Mass analysis was performed with an Agilent 6545 Q-TOF mass spectrometer in Auto MS/MS mode controlled using Agilent’s MassHunter Data Acquisition Version B.09.00. Analytes were ionized in positive mode electrospray ionization (ESI) using an Agilent Jet Stream source. The first 0.5 minutes and last 2 minutes of the chromatographic separation were diverted to waste. A capillary voltage of 3500 V and nozzle voltage of 1000 V was used for ESI, along with nebulizer and sheath gas (ultra-high purity nitrogen) at 350 °C to assist in ionization. For broadband MS analysis a mass range of m/z 100–1000 was analyzed a rate of 5 spectra/s and a time of 200 ms/spectrum. For each MS cycle, two precursors within m/z 200–600 and with at least 1000 counts abundance were automatically selected for MS/MS. Those precursors were then dynamically excluded for 0.1 minutes. To conserve cycle time, all IS compounds were placed on a static exclusion list, except fentanyl-D5 which was used as a control to ensure sample viability. To ensure identification of library components, a list of the compounds in the library was used for preferential precursor selection. Precursors were isolated with a medium isolation width (~4 Da wide) and fragmented by collision-induced dissociation (CID) at 20 eV and 40 eV. The fragments were acquired at a rate of 3 spectra/s and a time of 333.3 ms/spectrum across m/z 50–1000. The instrument was externally calibrated daily with Agilent low concentration ESI tuning mix, and each analysis internally calibrated with purine and HP-0921 (hexakis(1H, 1H, 3H-tetrafluoropropoxy)phosphazine) from Agilent’s ESI-TOF reference mass solution kit.

2.8. Creation of a Spectral Library using the FAS Kit and FAS V1

The molecular formula of the synthetic opioids, fentanyl analogs, or other associated compounds found in the FAS Kit, FAS V1, or available in-house were entered into a personal compound database and library (PCDL) along with their calculated monoisotopic mass using MassHunter PCDL Manager B.08.00 (Agilent). To acquire mass fragmentation spectra, each individual compound stock solution was diluted to 25 ng/mL in DI water and analyzed in triplicate. The retention time (RT) was averaged and added to the PCDL alongside the fragmentation spectra. A table of all compounds in the in-house PCDL can be found in supplemental information (Table S1).

2.9. Spectral Library Matching.

Chromatographic peaks were extracted in MassHunter Qualitative Analysis Workflows (Agilent, MassHunter Qualitative Analysis software version B.10) and identified by accurate mass and isotopic spacing using the Find-by-Formula algorithm against the in-house PCDL with a mass tolerance of ±5 ppm and RT tolerance of ±0.50 minutes. Only chromatographic peaks with a height greater than 7000 counts were extracted. Find by Formula’s match score is weighted based on mass (32.3%), isotope abundance (19.4%), isotopic spacing (16.1%), and RT accuracy (32.2%). The MS/MS spectra of the precursors identified by the Find by Formula were then used for library matching against the in-house PCDL, containing the reference CID spectra at 20 and 40 eV, using the “Identify Compounds” tool in Qualitative Analysis Workflows with an allowable mass error of ±10 ppm.

2.10. Method Validation.

This method was validated for both urine and plasma following SWGTOX guidelines, as described in the following paragraphs (Scientific Working Group for Forensic, 2013).

2.10.1. Lower Reportable Limit.

The lower reportable limit (LRL100) for urine and plasma was determined for the quality control compounds (Table 1) by spiking one blank pooled and three blank individual matrix (urine and plasma) samples with analytes at decreasing concentration levels (5 ng/mL to 0.075 ng/mL). Analysis was performed in triplicate each day across four days. The lowest concentration level in which the compound was positively identified across all 12 replicates was reported as the LRL100 for that matrix.

Table 1.

Evaluation of analyte matrix effects, extraction efficiency, and lower reportable limit (LRL100) in plasma and urine. Matrix effects and extraction efficiency shown is at 15 ng/mL.

| Analyte | Plasma | Urine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matrix Effects (%) | Extraction Efficiency (%) | LRL100 (ng/mL) | Matrix Effects (%) | Extraction Efficiency (%) | LRL100 (ng/mL) | |

| Fentanyl | −14.4 | 82.4 | 0.50 | −17.6 | 86.7 | 0.50 |

| Acetylfentanyl | −10.5 | 85.2 | 0.25 | −11.2 | 88.6 | 0.75 |

| Carfentanil | −12.2 | 84.0 | 0.75 | −16.5 | 88.6 | 1.00 |

| Cyclopropylfentanyl | −14.2 | 86.5 | 0.75 | −18.0 | 85.1 | 1.00 |

| Fluoroisobutyrylfentanyl | −23.1 | 86.4 | 1.00 | −27.1 | 87.0 | 0.75 |

| Furanylfentanyl | −10.1 | 81.5 | 2.50 | −14.8 | 81.7 | 1.00 |

| Methoxyacethylfentanyl | −9.2 | 82.0 | 0.50 | −9.3 | 88.1 | 1.00 |

| 4-ANPP | −12.3 | 63.1 | 1.00 | −17.6 | 71.3 | 1.00 |

| Norfentanyl | −17.5 | 91.6 | 2.50 | −54.5 | 92.1 | 5.00 |

| Naloxone | −26.1 | 48.9 | 2.50 | −31.6 | 43.3 | 5.00 |

2.10.2. Carryover.

Carryover was evaluated by injecting an extracted blank matrix immediately following injection of an extracted sample of quality control compounds at 100 ng/mL. This experiment was performed in triplicate.

2.10.3. Interference.

Fifty individual urine and 50 individual plasma reference samples, assumed to be unexposed, were analyzed to confirm the absence of matrix interferences. In addition, biomarkers of several drugs of misuse commonly associated with fentanyl use (i.e., cocaine, heroin, and tramadol) were also analyzed to confirm no interference with library compounds.

2.10.4. Extraction Efficiency and Matrix Effects.

Extraction efficiency was determined by comparing QC analytes spiked into matrix before and after extraction at both QC levels (2.0 and 15 ng/mL) and calculated as follows:

To determine matrix effects, solutions of the QC analytes spiked post extraction in urine/plasma and QC analytes spiked at the equivalent concentration level in DI water were prepared, analyzed, and compared to each other. The DI solutions were prepared at double the QC concentration levels, as the extraction process ultimately doubles the concentration of the analyte sample concentration for analysis. Matrix effects were then calculated using SWGTOX guidelines section 7.5.2 (Scientific Working Group for Forensic, 2013).

2.10.5. Extracted Stability.

Stability was assessed by extracting QC samples and storing at 10 °C for 24 hours before analysis. Samples were then evaluated to confirm all analytes were identified with the established criteria.

2.11. Method Characterization.

Twenty replicate analytical runs of QCL, QCH, and QCB were analyzed to evaluate internal standard abundance, retention time, and library scores. These analytical runs were extracted and analyzed by two analysts, with no more than two replicates per day, over the course of 10 separate days.

3. Results and Discussion.

3.1. Method Development

3.1.1. LC parameters.

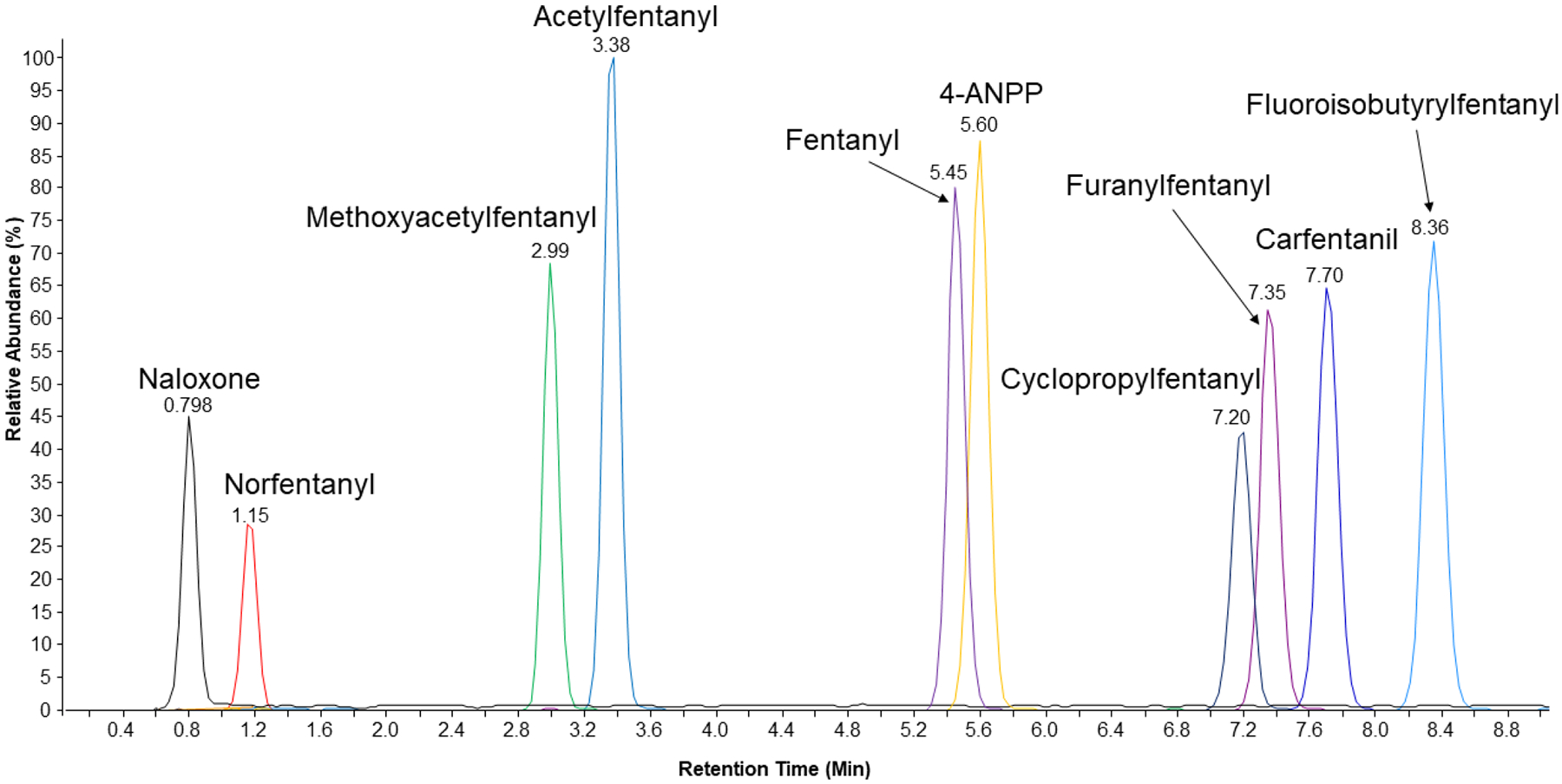

Ten synthetic opioids and related compounds were chosen and defined as QC compounds to optimize sample preparation and instrument parameters. These compounds were selected due to their frequency in recent illicit use, pharmacetical use, or association with synthetic opioid exposure or treatment (Emerging threat report). Contained within the QC compounds is one synthetic precursor (4-ANPP), one metabolite (norfentanyl), and six fentanyl analogs in addition to fentanyl. Naloxone, commonly used to treat opioid overdoses, is also included. Baseline LC separation was achieved for the compounds in the quality control solution, except two pairs of co-eluting peaks that are easily distinguished by mass. (Figure 1). To minimize source contamination, the LC eluent was diverted to waste for the first 30 seconds and last two minutes of the analytical run.

Figure 1.

TIC of all compounds in the quality control solution at 15 ng/mL in water after LC-QTOF analysis. Quality control solution contains a total of eight different fentanyl related compounds in addition to fentanyl. six of these compounds are fentanyl analogs, one is a synthetic precursor (4-ANPP), and one is a metabolite (norfentanyl). Naloxone is also studied due to its usage as treatment against opioid exposure.

3.1.2. MS Optimization and Library Creation.

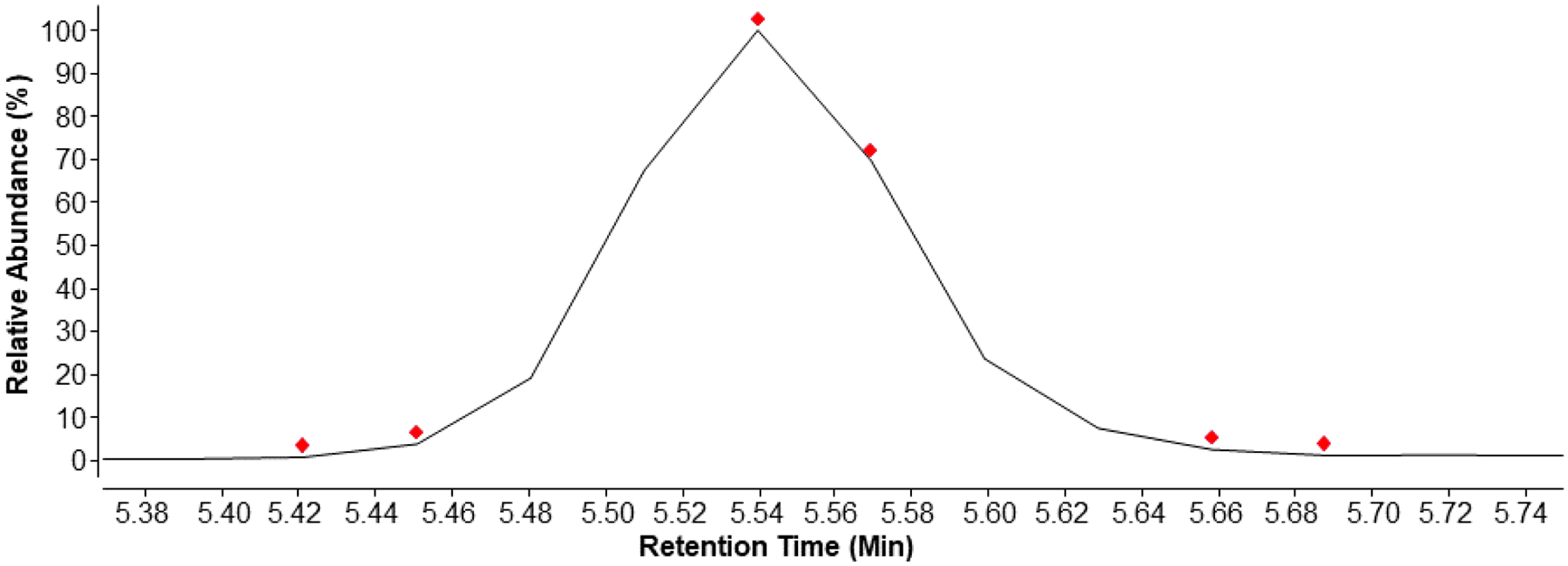

Agilent’s Auto MS/MS parameters were optimized to capture library compounds that may be found in a sample. A preferred list, comprised of exact m/z and retention times, was established to preferentially select library compounds for fragmentation. In the event of co-eluting compounds of interest, the most abundant ion from the preferred list was selected for fragmentation. When no preferred compounds were found, the instrument selected the most abundant ion present with a height greater than 1000 counts. After two fragmentation spectra of a given m/z were acquired, at both fragmentation energies, the compound was excluded for 0.1 minutes so other compounds may be selected. The red diamonds in Figure 2 indicate where fentanyl (black peak) was selected for fragmentation. The short exclusion duration (i.e., 5.46 to 5.54 min) permits the selection of other compounds, while fragmenting fentanyl at high abundance.

Figure 2.

Extracted Ion Chromatogram (m/z 337.2278 ± 0.0005) of fentanyl. Red diamonds indicate when MS/MS spectra were acquired, as triggered by the Auto MS/MS mode.

All compounds from the FAS Kit, FAS V1, internal standards, additional commercially available fentanyl analogs (e.g., carfentanil), and other compounds commonly detected in fentanyl exposure specimens (e.g., naloxone and heroin metabolites) were analyzed using these parameters to create the in-house spectral library for 174 fentanyl analogs and related compounds (Table S1).

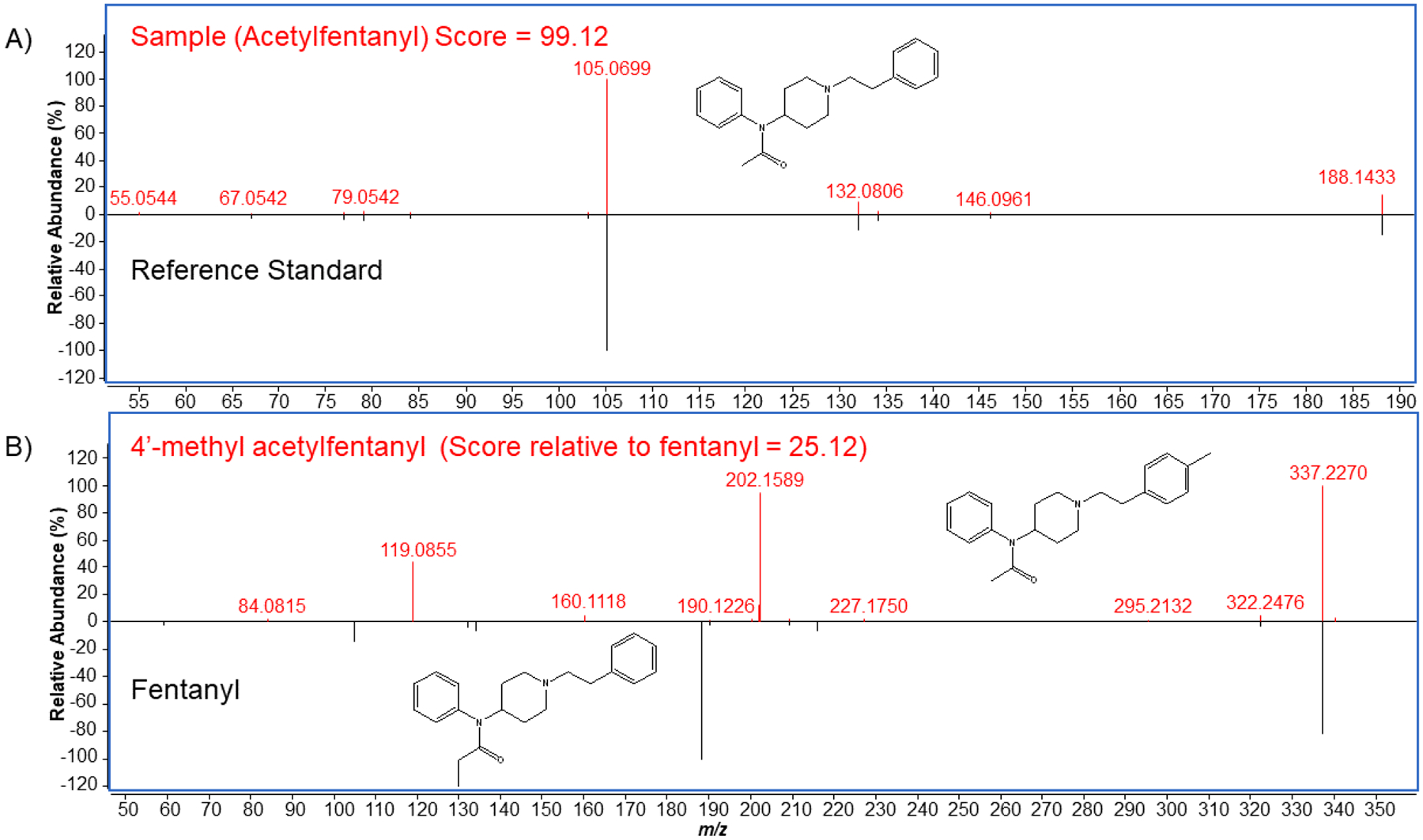

3.1.3. Match and Confirmation Criteria.

Twenty replicate analytical runs of the QCL, QCH, and QCB were used to characterize the method and set match criteria. To minimize false positives, chromatographic peaks with a height less than 7000 counts were not evaluated. Compounds with database scores, determined by mass, isotopic abundance, isotope spacing, and RT accuracy, greater than 40 were selected for library matching. Then the experimental fragmentation pattern was compared to a reference fragmentation pattern (Figure 3, A) to generate a library score. When a peak was identified with a library match, the library scores of the two fragmentation spectra (collected at 20 and 40 eV) were averaged. Only averaged library scores greater than 70 were accepted as a potential positive match, eliminating misidentification of potential isomers (Figure 3, B). Library matching requires a relatively broad RT window (± 0.5 minutes) to account for column or solvent variations that may occur since the compound RT was first measured and added to the library. For the analysis of samples, however, a narrower RT window is desired to ensure no false positive identifications or to distinguish between various isomers with similar fragmentation patterns that may all elute within the broad RT window. Therefore, for final identity confirmation, reference standards of all potential positive identifications were analyzed within 24 hours of the initial sample analysis, using the same column and mobile phase batch. The identity of the compound was confirmed when the mass error of the reference standard and unknown were within 5 ppm and the RT difference was less than 0.15 min of each other.

Figure 3.

Comparison of fragmentation spectra between A) acetylfentanyl and its reference standard within the library, and B) 4’-methyl acetylfentanyl and its isomer fentanyl. Acetylfentanyl has a close match with its reference standard giving a high match score of 99.12. Despite fentanyl and 4’-methyl acetylfentanyl being isomers, they have different fragmentation patterns due to the differing location of a methyl group, resulting in a poor match score (25.12) of 4’-methyl acetylfentanyl relative to the fentanyl.

3.2. Method Validation

Extraction efficiency and matrix effects were investigated for the QC compounds (Table 1). Data is only shown for 15 ng/mL but matched calculations for 2.0 ng/mL. Plasma extraction efficiencies ranged from 48.9 – 91.6%; urine extraction efficiencies ranged from 43.3 – 92.1%. The majority of the compounds had extraction efficiencies greater than 80% or above in both matrices. Only 4-ANPP and naloxone had lower extraction efficiencies, which could be attributed to their differences in chemical structures relative to fentanyl analogs. Matrix effects were below the SWGTOX guidelines of 25% with the exception of three compounds for urine and one for plasma (Table 1)(Scientific Working Group for Forensic, 2013). With the exception of fluoroisobutyrylfentanyl, the compounds with high matrix effects eluted at the extremes of the chromatographic run, which coincides with the elution of matrix components.

The LRL100 was determined for the QC compounds (Table 1). LRL100 for these compounds ranged from 0.25 – 1.00 ng/mL with the exception of norfentanyl and naloxone which were higher. In addition, LRL100 were higher in urine than plasma. Compounds with lower extraction efficiencies, higher matrix effects, or a combination had higher LRL100. The selected approach to determine LRL resulted in a conservative estimate to best describe method performance across time and variable conditions. Reported concentrations of fentanyl and fentanyl analogs following exposure have varied greatly, with fentanyl, carfentanil, acetylfentanyl, and furanylfentanyl concentrations ranging from 0.0102 ng/mL to 827 ng/mL in human matrices (Butler et al., 2018; Henderson, 1991; Martucci et al., 2018; Mochizuki et al., 2018; Shanks and Behonick, 2017; Sofalvi et al., 2017; Swanson et al., 2017). Although sensitivity may preclude the detection of all exposures due to delayed sample collection or opioid toxicity, this method has the capability to identify 174 fentanyl related compounds. This method can confirm the presence of analogs based on library match criteria, but the absence of an analyte cannot be definitively reported without characterization of the individual compound LRL.

Matrix interferences did not result in the positive identification of library compounds in the analysis of 50 individual urine samples and 50 individual plasma samples. However, fentanyl, acetylfentanyl, fluroisobutrylfentanyl, morphine, and norfentanyl were all positively identified in one of the individual plasma samples. Identification of fentanyl and acetylfentanyl was confirmed with a second method (data not shown). The addition of isotopically labeled standards or the metabolites of drugs commonly associated with fentanyl use did not result in any false positives.

Carryover was not observed in matrix blanks following a highly concentrated sample (100 ng/mL). Stability of processed samples was assessed over a period of 24 hours with no decrease in peak area counts.

3.3. Method Characterization

Three quality control materials (QCL, QCH, QCB) were extracted and analyzed in duplicates over the course of 10 days. All QC analytes were positively identified in QCL and QCH across all runs, with the exception of norfentanyl, which had an LRL100 above QCL concentration. No false positives were detected in the QCB.

3.4. Analysis of evaluation samples

In analysis of the three CAP evaluation samples, eight compounds were positively identified (Table 2) with library scores greater than 70 and mass error less than 5 ppm. A contemporaneous reference standard was analyzed within 24 hours for each positive identification and retention times were compared (Table 2) to confirm identification.

Table 2.

Positive compound confirmations from three spiked whole blood CAP evaluation samples.

| Sample ID | Compounds Identified | ΔRT* (min) | Mass Error (ppm) | Library Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOB-01 | Acetylfentanyl | 0.02 | 0.72 | 99.1 |

| Acrylfentanyl | 0.00 | 1.55 | 96.3 | |

| Carfentanil | 0.06 | 1.03 | 95.5 | |

| NOB-02 | α-Methylfentanyl | 0.00 | 1.04 | 98.8 |

| 4-ANPP | 0.03 | 1.50 | 99.6 | |

| Furanylfentanyl | 0.00 | 1.53 | 91.4 | |

| NOB-03 | para-Fluorofentanyl | −0.03 | 1.50 | 98.4 |

| U-47700 | −0.03 | 1.67 | 99.1 |

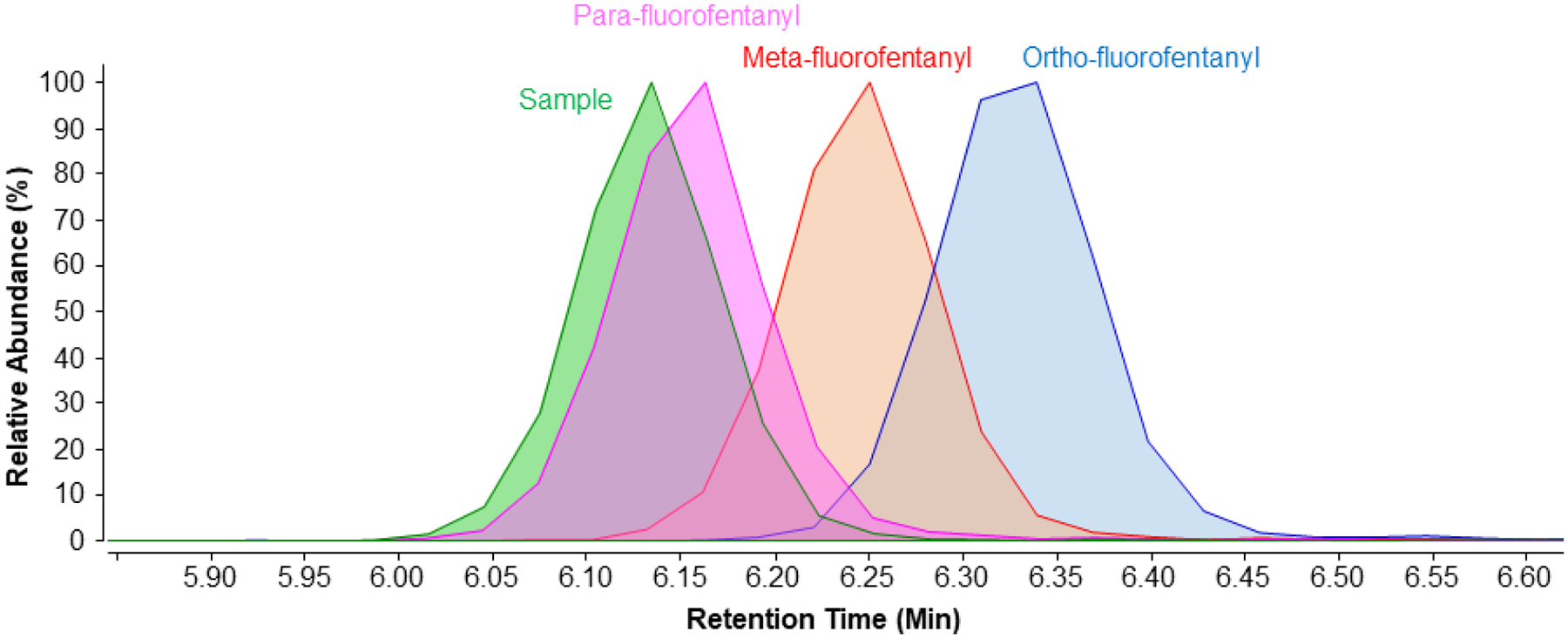

During the analysis of NOB-03, there were three possible isomeric identifications for a single peak: para-fluorofentanyl, meta-fluorofentanyl, and ortho-fluorofentanyl. As demonstrated from the chromatogram of all three standards and the CAP sample peak (Figure 4) the retention time of the sample most closely matches that of para-fluorofentanyl. With the similar retention times and library match we confirmed the peak as para-fluorofentanyl. Without the addition of the FAS Kit and the FAS V1 materials into this work’s newly implemented spectral database, the authors would not have known that the method would chromatographically separate the fluorofentanyl isomers ortho, meta, and para. Additionally, if the specimen had contained the ortho or meta isomers, and the laboratory was limited to a reference standard for only the para-fluorofentanyl, the method would not have been able to distinguish the specific fluorofentanyl isomer present, a potentially important piece of information critical to exposure surveillance. The application of the FAS Kit in this work, therefore, demonstrates the ability of the new analytical reference materials to expand opioid testing capabilities. The CAP NOB survey report, received after analysis, confirmed that para-fluorofentanyl was spiked into the sample, in agreement with our identification. Even with retention time tolerances and tight mass error criteria, this demonstrates the importance of analyzing known standards to positively identify unknown peaks, preferably within 24 hours as requested by a number of data reporting programs. In addition to the para-fluorofentanyl, all synthetic opioid-related compounds identified in table 2 were confirmed by the CAP NOB survey report to be found in the samples indicating there were no false positives. In addition, there were no false negatives, confirmed by the CAP NOB survey report.

Figure 4.

Extracted ion chromatrogram (m/z 355.2185 ± 0.0005) overlay of the evaluation sample NOB-03 (green) and separate standards of para-fluorofentanyl (pink), meta-fluorofentanyl (red), and ortho-fluorofentanyl (blue) from the FAS Kit (all isomers). The evaluation sample was positively identified as the para-fluorofentanyl isomer due to the similar retention times.

4. Conclusions

A spectral library and detection method for fentanyl analogs and related compounds was developed for exposure analysis in human urine and plasma using LC-QTOF instrumentation. This method was validated for a subset of compounds using SWGTOX guidelines with lower reportable limits ranging from 0.25 to 2.5 ng/mL. The spectral library of 174 compounds used in this work was created to expand the laboratory’s opioid testing capabilities for emerging fentanyl-related compounds. The library was heavily influenced by its inclusion of the product line of Traceable Opioid Material§ Kits, specifically the FAS Kit (120 compounds) and FAS V1 (30 compounds). The effective use of this method was confirmed by its application in the analysis of CAP NOB survey samples, where the correct synthetic opioid-related analytes were identified even when isomers were present. This method provides a much-needed resource toward expanding laboratory synthetic opioid testing capabilities and identifying emerging fentanyl analogs and related compounds in human matrices.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

§TRACEABLE OPIOID MATERIAL, TOM KITS, and the TOM KITS logo are marks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The CDC appreciates the College of American Pathologists’ (CAP) assistance in providing essential information of CAP proficiency testing samples used in this program.

This work was funded through CDC’s National Center for Injury prevention and Control. The authors would like to especially thank the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and the many CDC offices that provided support in the areas of contracting, policy, communications, ethics, technology transfer, general counsel, and administrative services.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer

Publisher's Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, or the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, or the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Fentanyl Analog Screening Kits. https://www.caymanchem.com/forensics/faskit/. Access Date 07/02/2019.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2017. Fentanyl and its Analogues - 50 Years On. Global Smart Update. UNODC, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Angelini DJ, Biggs TD, Maughan MN, Feasel MG, Sisco E, Sekowski JW, 2019. Evaluation of a lateral flow immunoassay for the detection of the synthetic opioid fentanyl. Forensic Sci Int 300, 75–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchalter S, Marginean I, Yohannan J, Lurie IS, 2019. Gas chromatography with tandem cold electron ionization mass spectrometric detection and vacuum ultraviolet detection for the comprehensive analysis of fentanyl analogues. Journal of Chromatography A 1596, 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busardo FP, Carlier J, Giorgetti R, Tagliabracci A, Pacifici R, Gottardi M, Pichini S, 2019. Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Assay for Quantifying Fentanyl and 22 Analogs and Metabolites in Whole Blood, Urine, and Hair. Front Chem 7, 184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler DC, Shanks K, Behonick GS, Smith D, Presnell SE, Tormos LM, 2018. Three Cases of Fatal Acrylfentanyl Toxicity in the United States and a Review of Literature. J Anal Toxicol 42, e6–e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Mañas MC, Ferrer I, Thurman EM, Sánchez Pérez JA, Agüera A, 2019. Identification of opioids in surface and wastewaters by LC/QTOF-MS using retrospective data analysis. Science of The Total Environment 664, 874–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEA, 2018. 2018 Emerging Threat Report. https://ndews.umd.edu/resources/dea-emerging-threat-reports. Access Date: 6/26/2019.

- Fogarty MF, Papsun DM, Logan BK, 2018. Analysis of Fentanyl and 18 Novel Fentanyl Analogs and Metabolites by LC–MS-MS, and report of Fatalities Associated with Methoxyacetylfentanyl and Cyclopropylfentanyl. Journal of Analytical Toxicology 42, 592–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie TJ, Gandolfi AJ, Vaughan RW, 1981. Gas Chromatographic Determination of Fentanyl and its Analogues in Human Plasma. Journal of Analytical Toxicology 5, 133–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrieri D, Kjellqvist F, Kronstrand R, Green H, 2019. Validation and Cross-Reactivity Data for Fentanyl Analogs With the Immunalysis Fentanyl ELISA. J Anal Toxicol 43, 18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson GL, 1991. Fentanyl-Related Deaths Demographics, Circumstances, and Toxicology of 112 Cases. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 422–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martucci HFH, Ingle EA, Hunter MD, Rodda LN, 2018. Distribution of furanyl fentanyl and 4-ANPP in an accidental acute death: A case report. Forensic Science International 283, e13–e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misailidi N, Athanaselis S, Nikolaou P, Katselou M, Dotsikas Y, Spiliopoulou C, Papoutsis I, 2019. A GC-MS method for the determination of furanylfentanyl and ocfentanil in whole blood with full validation. Forensic Toxicol 37, 238–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki A, Nakazawa H, Adachi N, Takekawa K, Shojo H, 2018. Postmortem distribution of mepirapim and acetyl fentanyl in biological fluid and solid tissue specimens measured by the standard addition method. Forensic Toxicology 37, 27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojica MA, Carter MD, Isenberg SL, Pirkle JL, Hamelin EI, Shaner RL, Seymour C, Sheppard CI, Baldwin GT, Johnson RC, 2019. Designing traceable opioid material* kits to improve laboratory testing during the U.S. opioid crisis. Toxicology Letters 317, 53–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounteney J, Giraudon I, Denissov G, Griffiths P, 2015. Fentanyls: Are we missing the signs? Highly potent and on the rise in Europe. International Journal of Drug Policy 26, 626–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble C, Weihe Dalsgaard P, Stybe Johansen S, Linnet K, 2018. Application of a screening method for fentanyl and its analogues using UHPLC-QTOF-MS with data-independent acquisition (DIA) in MS(E) mode and retrospective analysis of authentic forensic blood samples. Drug Test Anal 10, 651–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Salomone A, Bigiarini R, Vincenti M, Acosta P, Tofighi B, 2019. Testing hair for fentanyl exposure: a method to inform harm reduction behavior among individuals who use heroin. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 45, 90–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmquist KB, Swortwood MJ, 2019. Data-independent screening method for 14 fentanyl analogs in whole blood and oral fluid using LC-QTOF-MS. Forensic Sci Int 297, 189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge E, Trobbiani S, Stockham P, Charlwood C, Kostakis C, 2018. A Case Study Involving U-47700, Diclazepam and Flubromazepam-Application of Retrospective Analysis of HRMS Data. J Anal Toxicol 42, 655–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruangyuttikam W, Law MY, Rollins DE, Moody DE, 1990. Detection of Fentanyl and its Analogs by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay. Journal of Analytical Toxicology 14, 160–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomone A, Palamar JJ, Bigiarini R, Gerace E, Di Corcia D, Vincenti M, 2019. Detection of Fentanyl Analogs and Synthetic Opioids in Real Hair Samples. J Anal Toxicol 43, 259–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G, 2019. Drugs and Opioid Involved Overdose Deaths - United States 2013–2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 67, 1419–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuttler J, White PF, 1984. Optimization of the Radioimmunoassays for Measureing Fentanyl and Alfentanil in Human Serum. Anesthesiology 61, 315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scientific Working Group for Forensic, T., 2013. Scientific Working Group for Forensic Toxicology (SWGTOX) standard practices for method validation in forensic toxicology. J Anal Toxicol 37, 452–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour C, Shaner RL, Feyereisen MC, Wharton RE, Kaplan P, Hamelin EI, Johnson RC, 2019. Determination of Fentanyl Analog Exposure Using Dried Blood Spots with LC-MS-MS. J Anal Toxicol 43, 266–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanks KG, Behonick GS, 2017. Detection of Carfentanil by LC-MS-MS and Reports of Associated Fatalities in the USA. J Anal Toxicol 41, 466–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofalvi S, Schueler HE, Lavins ES, Kaspar CK, Brooker IT, Mazzola CD, Dolinak D, Gilson TP, Perch S, 2017. An LC–MS-MS Method for the Analysis of Carfentanil, 3-Methylfentanyl, 2-Furanyl Fentanyl, Acetyl Fentanyl, Fentanyl and Norfentanyl in Postmortem and Impaired-Driving Cases. Journal of Analytical Toxicology 41, 473–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strayer KE, Antonides HM, Juhascik MP, Daniulaityte R, Sizemore IE, 2018. LC-MS/MS-Based Method for the Multiplex Detection of 24 Fentanyl Analogues and Metabolites in Whole Blood at Sub ng mL(−1) Concentrations. ACS Omega 3, 514–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson DM, Hair LS, Strauch Rivers SR, Smyth BC, Brogan SC, Ventoso AD, Vaccaro SL, Pearson JM, 2017. Fatalities Involving Carfentanil and Furanyl Fentanyl: Two Case Reports. Journal of Analytical Toxicology 41, 498–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooy HH, 1981. The assay of fentanyl and its metabolites in plasma of patients using gas chromatography with alkali flame ionisation detection and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. JOurnal of Chromatography 233, 85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardanyan RS, Hruby VJ, 2014. Fentanyl-related compounds and derivatives: current status and future prospects for pharmaceutical applications. Future Med Chem 6, 385–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Huynh K, Barhate R, Rodrigues W, Moore C, Coulter C, Vincent M, Soares J, 2011. Development of a homogeneous immunoassay for the detection of fentanyl in urine. Forensic Sci Int 206, 127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.