Abstract

Introduction

While pediatricians should receive training in the care of transgender youth, a paucity of formal educational curricula have been developed to train learners to care for this vulnerable population.

Methods

We developed a curriculum including six online modules and an in-person afternoon session observing clinic visits in a pediatric gender clinic. Learners—fourth-year medical students, interns, and nurse practitioner trainees—received protected time during an adolescent medicine rotation to complete the online modules (total duration: 77 minutes). For 20 learners, we assessed the impact of the entire curriculum—online modules and in-person observation—on self-perceived knowledge of considerations for transgender youth. For 31 learners, we assessed the effect of the online modules alone on knowledge and self-efficacy. Descriptive analyses illustrated changes in educational domains by learner group.

Results

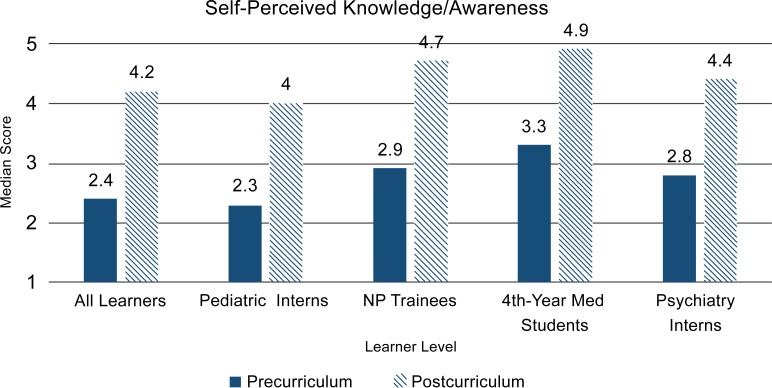

On evaluations of the entire curriculum (modules and observation), median self-perceived knowledge scores (1 = not at all knowledgeable/aware, 5 = extremely knowledgeable/aware) increased within learner groups: pediatric interns (from 2.3 to 4.0), nurse practitioner trainees (from 2.9 to 4.7), fourth-year medical students (from 3.3 to 4.9), and psychiatry interns (from 2.8 to 4.4). Assessment of learners completing only the online modules demonstrated increases in median knowledge and self-efficacy scores within learner groups. All learner groups highly valued the curriculum.

Discussion

Our curriculum for multidisciplinary learners in the care of transgender youth was successful and well received. Increasing learner knowledge and self-efficacy is an important step towards skill development in patient care for the transgender youth population.

Keywords: Transgender, Gender Dysphoria, Gender Diverse, Pubertal Blockers, Gender-Affirming Hormones, Online Modules, Adolescent Medicine, Online/Distance Learning, Pediatric Endocrinology, Pediatrics, Primary Care, Diversity, Inclusion, Health Equity

Educational Objectives

By the end of this activity, learners will be able to:

-

1.

Define the different elements of gender.

-

2.

Describe how transgender youth present to care at different ages and developmental stages.

-

3.

Explore questions to obtain different aspects of a transgender youth's gender history and psychosocial history.

-

4.

Describe the different stages of pubertal development and the role of pubertal progression in potentially worsening gender dysphoria for transgender youth.

-

5.

Identify the psychosocial and medical supports available to transgender youth and their families.

Introduction

Transgender youth are disproportionally affected by poor psychosocial outcomes such as depression, anxiety, suicidality, and substance abuse.1–3 Fortunately, parental acceptance and psychosocial support can improve mental health outcomes for these young people.4–6 Furthermore, medical support in the form of pubertal blockers and gender-affirming hormones can also improve psychological distress.7 Despite professional guidelines that recommend psychological and medical support for these youth,8,9 pediatric medical providers are not confident in their ability to provide transgender-specific care, and they cite lack of medical training and education as a significant barrier to their provision of these services.10

Overall, there has been a lack of educational materials—beyond published review articles and clinical guidelines8,9,11–17—that provide instruction on gender-affirming medical treatment and psychosocial supports for transgender children and adolescents. Other educational resources include a PowerPoint presentation and case videos provided by the organization Physicians for Reproductive Health that focus on primary care considerations for transgender youth.18 Gender Spectrum is an organization with online materials for supporting transgender youth and their families.19 However, these resources are not structured experiences for learners, and learner satisfaction and program efficacy have not been formally evaluated. One MedEdPORTAL publication contains pediatric-specific information within a PowerPoint presentation, but the pediatric transgender population is not the sole emphasis of the curriculum, and it does not emphasize the developmental perspective and role of family for transgender youth.20

Pediatric providers play an important role in the primary care and subspecialty care of transgender children and adolescents. Primary care providers may be the first clinicians from whom transgender youth and their families seek support. Subspecialists also inevitably encounter transgender youth because, similar to cisgender youth, transgender youth experience complex, chronic diseases. The American Academy of Pediatrics acknowledged in a policy statement the crucial need for pediatric providers to provide comprehensive care to these youth, further endorsing the importance of pediatric providers’ education in interacting with transgender youth in a sensitive, gender-affirming manner while being aware of the basic medical and psychosocial considerations for these young people.21

Recognizing the importance of exposing pediatric learners to transgender care and the paucity of educational materials, we developed and evaluated a comprehensive pediatric transgender curriculum. Our online curriculum aimed to do the following:

-

•

Focus solely on transgender children and adolescents through a developmental lens.

-

•

Utilize an independent model of learning through use of online module technology.

-

•

Target multidisciplinary learners who will provide care to children and adolescents.

-

•

Combine with clinical observational experiences with transgender youth as available.

Methods

Target Learners

We embedded the curriculum within the adolescent medicine rotation because all pediatric residents were required to do a 4-week rotation in adolescent medicine per the Accreditation Counsel for Graduate Medical Education. Our key mission of the curriculum was for all pediatric residents at our institution to receive instruction and training in pediatric transgender medicine prior to graduating. Appreciating the importance of multidisciplinary care for transgender youth, we expanded our target learners to include learners from other specialties who would likely clinically encounter transgender youth.

Ultimately, our target learners for the curriculum were medical students and trainees on their adolescent medicine rotation. Our target learners included pediatric interns on a required 1-month rotation, psychiatry interns on a 1-month elective rotation, and fourth-year medical students on a 1-month advanced elective. Additionally, we included pediatric and family medicine nurse practitioner (NP) trainees with a yearlong longitudinal experience with our adolescent medicine division. As a requirement for being specialized in pediatric and family medicine, NP trainees were required to have clinical exposure to adolescent medicine and to participate in adolescent medicine didactics. As the curriculum was part of adolescent medicine didactics, we gave NP trainees the option to participate in the transgender curriculum. Of note, all pediatric and family medicine NP trainees participated.

Prerequisite knowledge needed for learners to complete our curriculum included physiology of reproductive systems and childhood and adolescent development.

Curricular Components

The first component of our curriculum comprised six online modules (Appendices A–F), which took learners through virtual clinical encounters with three transgender youth. We posted the modules on the Collaborative Learning Environment, our institution's dedicated educational platform. We have previously described the development of the modules in detail.22,23 We included the login information for the curriculum within the Collaborative Learning Environment in the rotation orientation materials provided approximately 1 week prior to the learners starting. The original modules described in our prior publications were interactive—that is, they allowed learners to click on terms to reveal definitions—but our institution did not continue the license for the Articulate Studio software. Therefore, we converted the modules to videos, thereby removing the interactivity, to allow for their ongoing use with our platform upgrades and ultimately for future dissemination.

The six modules included the following:

-

•

Module 1: Construct of Gender—duration: 8:38 minutes.

-

•

Module 2: Gender History—duration: 19:00 minutes.

-

•

Module 3: Psychosocial History—duration: 15:48 minutes.

-

•

Module 4: Physical Examination—duration: 11:10 minutes.

-

•

Module 5: Assessment and Psychosocial Plan—duration: 8:08 minutes.

-

•

Module 6: Medical Plan—duration: 14:19 minutes.

We individually assigned learners 2 hours of protected time during their adolescent medicine rotation to complete the online modules, which had a collective duration of 1 hour and 17 minutes. One learner at a time was excused from an afternoon clinic as protected time to complete the modules. We instructed learners to access the curriculum using their own personal computer or computers available in our institution's libraries throughout the campus. Allotting protected time to complete the modules optimized the chances of learners completing this independent learning experience. Of note, we compiled question prompts featured throughout the modules in Appendix G for reference by MedEdPORTAL users.

The second component of our curriculum was a 1-afternoon observership in our pediatric transgender clinic. We assigned each learner to one pediatric gender clinic during their 1-month rotation, and we scheduled their observership approximately 1 week after their protected time for completing the modules. Of note, we assigned a maximum of two learners to each clinic session so as not to overwhelm the families and clinic space. On the day of the observation, learners attended the clinic's 1-hour preclinical conference where providers from the disciplines of pediatric endocrinology, adolescent medicine, psychology, and social work introduced themselves and briefly described their role on the team. During this preclinical conference, the team members presented patients on the 4-hour clinic schedule. We then allowed learners to primarily observe clinical care provided to transgender youth by medical faculty members. At the beginning of the visit and prior to the learner entering the room, the medical faculty member asked the family's permission for the learner to observe. Once permission was granted, the learner entered the room and observed the medical faculty member taking a history, performing a physical exam, and counseling the patient and family. Typically, we allowed learners to see two patients presenting for new evaluations and three to four patients presenting for follow-up visits. Between patient visits, we encouraged learners to ask any questions they had regarding patient care. Additionally, for new patient evaluations, we allowed learners to shadow the psychologists during their portion of the evaluation. At the end of the clinic day, we informally asked the learners if they had any further questions and any thoughts or comments regarding the clinic experience.

Evaluations

Phase 1—the entire curriculum

In the first phase of our evaluation, we assessed the impact of the curriculum on learner self-perceived knowledge and awareness of psychosocial and medical considerations for transgender youth and learner satisfaction.22 For this phase, we evaluated the entire curriculum—inclusive of both the online modules and the observership. At the end of their adolescent medicine rotation, we asked learners to complete a paper assessment (Appendix H). Learners completed this assessment on the last Friday morning of their rotation after the general adolescent medicine didactics; the assessment took approximately 10 minutes to complete. It asked learners to complete demographic items and also items prompting them to reflect on and rate their level of knowledge/awareness on transgender-related issues prior to the curriculum and after having completed the curriculum. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all knowledgeable/aware, 5 = extremely knowledgeable/aware). We calculated the self-perceived knowledge/awareness scores by averaging the summed items for each learner. We compared pre/post statistical median scores for all learners via Wilcoxon signed rank tests. We calculated median scores within each learner level but did not conduct statistical comparisons among learner levels given the small numbers within each level. We also assessed curriculum satisfaction with items using 5-point Likert scales (1 = very unsatisfied, 5 = very satisfied). Satisfaction questions included the following:

-

•

“How satisfied are you with the overall quality of this curriculum?”

-

•

“Overall, how satisfied are you with the quality of the online modules?”

-

•

“How satisfied are you with the quality of the gender clinic experience?”

We compared median satisfaction scores within learner level but did not perform statistical comparisons within learner level given the small numbers.

Phase 2—online modules only

With further dissemination of our curriculum in mind, we recognized that not all institutions have pediatric gender clinics available for learner observerships. Therefore, we formulated a second phase of evaluation to assess the impact of the online modules as a stand-alone training.23 For this evaluation phase, learners completed a paper precurriculum assessment (Appendix I) on the first day of their rotation during orientation. Learners also completed a paper postmodule assessment (Appendix J) on the last Friday morning of their rotation after the general adolescent medicine didactics. These assessments took approximately 10 minutes to complete. Both assessments included nine objective knowledge items with quiz questions (answer key: Appendix K), 24 self-perceived knowledge/awareness questions asking learners to rate how knowledgeable/aware they were regarding transgender-related considerations, and 13 self-efficacy items asking learners to rate their confidence in evaluating and counseling transgender youth. Objective knowledge scores ranged from 0% to 100% correct on the nine-item quiz. Self-perceived knowledge/awareness scores were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all knowledgeable/aware, 5 = extremely knowledgeable/aware), and we calculated scores by averaging the summed items for each learner. Self-efficacy scores were on a 10-point Likert scale (1 = not at all confident, 10 = completely confident), and we calculated scores by averaging the summed items for each learner. We calculated median scores within each learner level but did not conduct statistical comparisons among learner levels given the small numbers within each level. We also assessed curriculum satisfaction with items using 5-point Likert scales. For the question “Overall, how satisfied are you with the quality of the online modules?”, learners rated satisfaction on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very unsatisfied, 5 = very satisfied ). We asked learners asked to rate their level of agreement with two additional items: “The material presented in this curriculum will be useful to me in caring for transgender youth” and “I expect to use the information gained from this curriculum.” We asked learners to rate level of satisfaction on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). We compared median satisfaction scores within learner level but did not perform statistical comparisons within learner level given the small numbers.

Results

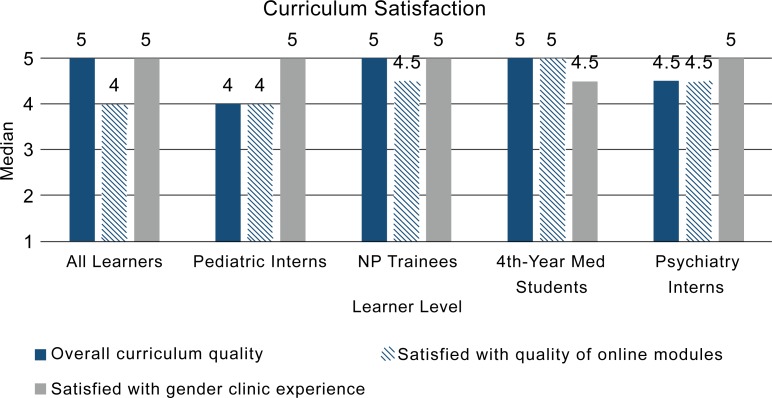

We have described the impact of the entire curriculum and the impact of the online modules as a stand-alone training in prior publications.22,23 For the Phase 1 evaluation of the entire curriculum, 20 learners participated. They had a statistically significant improvement in self-perceived knowledge/awareness of transgender-related considerations; furthermore, they highly valued the entire curriculum and each of its individual components.22 As a collective group, learners had statistically significant improvement in self-perceived knowledge/awareness when comparing pre- and postmedians.22 Because the number of learners per group was too small (12 pediatric interns, four NP trainees, two fourth-year medical students, and two psychiatric interns), we did not have the necessary power to perform statistical subanalyses. However, descriptive analyses with median self-perceived knowledge/awareness scores stratified by learner group suggest that self-perceived knowledge/awareness scores trended towards improvement for each group (Figure 1). Additionally, each learner group reported high satisfaction scores for the curriculum as a whole, the online modules alone, and the gender clinic observation (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Phase 1 evaluation: self-perceived knowledge/awareness median scores by learner level. Pre/post statistical comparisons for all learners had p values of <.001. Abbreviation: NP, nurse practitioner.

Figure 2.

Phase 1 evaluation: postcurriculum median satisfaction scores by learner level. Abbreviation: NP, nurse practitioner.

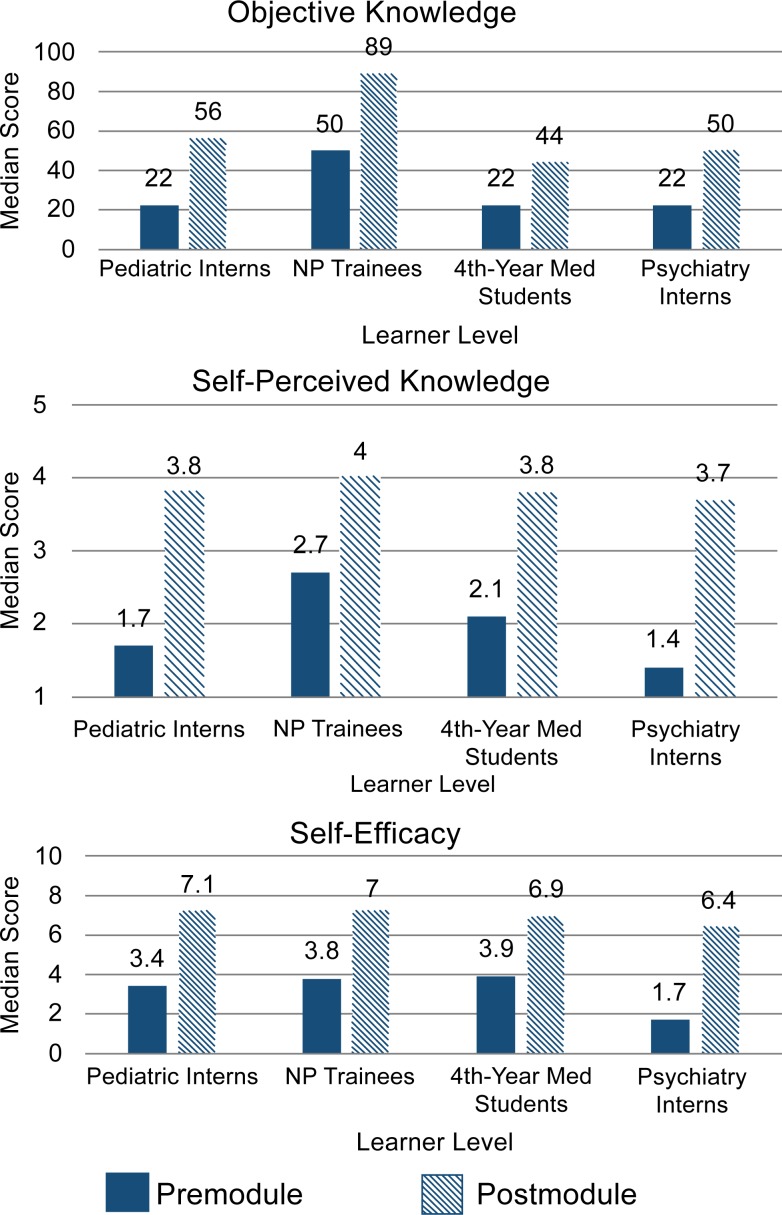

For the Phase 2 evaluation, 31 learners completed the stand-alone training of the online modules. As noted in prior publications, our learners as a collective group had statistically significant improvements in objective knowledge scores, self-perceived knowledge scores, and clinical self-efficacy in evaluating and counseling transgender youth.23 Again, the small number of learners per group (18 pediatric interns, six NP trainees, five fourth-year medical students, and two psychiatric interns) did not allow statistical group comparisons for the educational domains. However, descriptive analyses suggest that each learner group had scores that trended towards improvement in objective knowledge scores, self-perceived knowledge/awareness scores, and self-efficacy scores (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Phase 2 evaluation: pre- and postmodule median educational parameter scores by learner level. Abbreviation: NP, nurse practitioner.

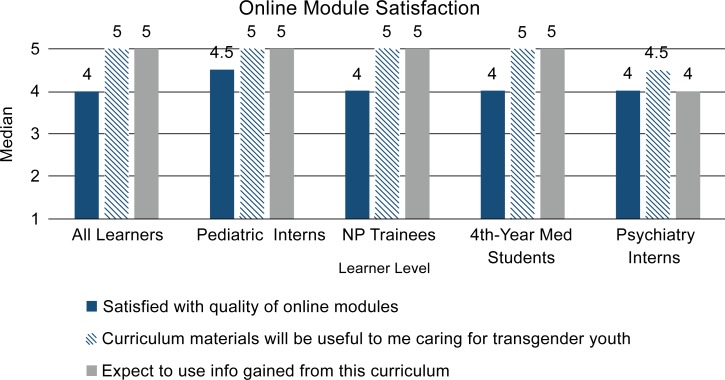

Furthermore, each learner group reported high satisfaction scores for the online modules. Additionally, each group had high levels of agreement that the curriculum would be helpful in caring for transgender youth and that they expected to use information gained from the curriculum (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Phase 2 evaluation: postmodule median satisfaction by learner level. Abbreviation: NP, nurse practitioner.

Discussion

Our curriculum improved perceived self-efficacy, perceived knowledge, and objective knowledge in the care and counseling of transgender youth among our learners, including advanced students and interns. Although transgender youth clinical programs and specialists do not exist at every training site, our online curriculum alone has demonstrated improved self-efficacy and knowledge and is easily adaptable to other sites, broadening potential experiences for learners. Given the success of our curriculum and its easy portability, we believe it can be easily integrated into other training programs with similar success. Answering the American Academy of Pediatrics’ call, our curriculum is a first step in enlisting pediatric clinicians to adequately support transgender youth and their care.21

One of the additional strengths of our curriculum is that it demonstrated improvement in multiple educational domains for different types of learners: fourth-year medical students, pediatric interns, psychiatry interns, pediatric NP trainees, and family medicine NP trainees. Although the numbers of each learner type were too small to draw conclusions regarding the differential curricular impact on learner type, descriptive analyses suggest a trend of improvement for each educational domain for each learner group. The pediatric interns, pediatric NP trainees, and family medicine NP trainees were differentiated to have future clinical careers that involve children and adolescents. On the other hand, the fourth-year medical students and psychiatry interns were less differentiated and may or may not go into specialties or subspecialties that involve youth. Even with these different levels of differentiation, all of the learner groups seemed to have benefited from the curriculum, highly valued the experience, and expected to use what they had learned from the curriculum in the future.

The biggest challenge to implementing our curriculum was ensuring that trainees had protected time to complete the modules. This may be a challenge for other institutions that want to implement our curriculum. For our adolescent medicine rotation, learners had inpatient duties typically in the morning and clinics in the afternoon. It was a challenge to balance the patient care needs of our inpatient and outpatient settings with the educational needs of the learners on our rotation. Ultimately, our division prioritized our trainees’ participation in the curriculum and recognized the importance of them receiving training. The presented data suggest that the curriculum is effective at improving knowledge and self-efficacy. Additionally, during end-of-rotation faculty feedback with trainees, learners reported that the transgender youth curriculum was one of their most favored parts of the rotation.

Pediatric transgender medicine is an of active area of research, and gender-affirming terminology is ever evolving to be optimally inclusive and affirming to the gender-diverse community. We developed our online modules using up-to-date information and affirming terminology at the time of its creation. A limitation of our curriculum is that some of the module content and references may not be the most up-to-date or all-inclusive at the time of this publication. As examples, since the creation of the modules, there has been more research pertaining to chest binding,24 and there is a more current version of the Genderbread Person, which is used to explain gender to youth.25 Additionally, our modules do not cite other resources, such as the World Professional Association for Transgender Health,9 the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association,26 the American Academy of Pediatrics’ policies on LGBTQ youth and care,27 and the World Health Organization,28 that may be helpful for those learning to provide gender-affirming care. We also opted to use an earlier version of the HEEADSSS assessment as the framework for evaluating gender history of a transgender youth rather than the more recent version.29 Finally, we recognize that some terminology currently may not be as frequently used or may have been replaced by other terminology. For example, preferred name and preferred pronouns have been commonly replaced by chosen name/pronoun or affirmed name/pronoun. Unfortunately, we were not able to change terminology or add additional citations throughout the online modules. It is our goal for our curriculum to be one of many tools to train pediatric providers in being more affirming of gender-diverse youth and to start discussions within educational environments regarding the most affirming language.

Future curricular development based on this work include adding aims that allow participants to advance their learning to a higher proficiency, looking at Bloom's taxonomy. It is important for learners to have opportunities for mastery exercises to further build their self-efficacy, develop their skill, and receive formative feedback prior to working with this vulnerable population. In order to do this, we will add standardized patient encounters to our curriculum. In addition to completing a self-assessment, learners will receive feedback from the standardized patients as well as faculty observers. We also aim to offer our curriculum to other learners, including practicing providers who may not have received formal training in providing care to transgender youth.

Appendices

- Module 1 Construct of Gender.mp4

- Module 2 Gender History.mp4

- Module 3 Psychosocial History.mp4

- Module 4 Physical Examination.mp4

- Module 5 Assessment and Psychosocial Plan.mp4

- Module 6 Medical Plan.mp4

- Question Prompts for Modules 1-3.docx

- Entire Curriculum Retrospective Pre- and Postassessment.docx

- Preassessment Online Module Only.docx

- Postassessment Online Module Only.docx

- Answer Key for Objective Knowledge Questions.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Sean Buckelew for his contribution of animations for the online modules, Salvador Oropesa for his contribution as creative design consultant for the online modules, and Lisa Leiva from the University of California, San Francisco, Learning Tech Group for her technical assistance with the modules.

Disclosures

None to report.

Funding/Support

We would like to acknowledge our primary funding source: the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), Academy of Medical Educators Innovations Funding for Education Grant. Additional support was provided by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, under a Cooperative Agreement UA6MC27378 for the Adolescent and Young Adult Research Network, by the HRSA/MCHB Leadership Education in Adolescent Health (LEAH) training grant T71-MC00003, and also by the UCSF Office of Diversity and Outreach.

Ethical Approval

The University of California, San Francisco, Institutional Review Board approved this study.

References

- 1.Becerra-Culqui TA, Liu Y, Nash R, et al.. Mental health of transgender and gender nonconforming youth compared with their peers. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20173845 https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veale JF, Watson RJ, Peter T, Saewyc EM. Mental health disparities among Canadian transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60(1):44–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez-Brumer A, Day JK, Russell ST, Hatzenbuehler ML. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation among transgender youth in California: findings from a representative, population-based sample of high school students. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(9):739–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Travers R, Bauer G, Pyne J, Bradley K, Gale L, Papadimitriou M. Impacts of strong parental support for trans youth: a report prepared for the Children's Aid Society of Toronto and Delisle Youth Services. TransPULSE website. http://transpulseproject.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Impacts-of-Strong-Parental-Support-for-Trans-Youth-vFINAL.pdf. Published October 2, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill DB, Menvielle E, Sica KM, Johnson A. An affirmative intervention for families with gender variant children: parental ratings of child mental health and gender. J Sex Marital Ther. 2010;36(1):6–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230903375560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson EC, Chen Y-H, Arayasirikul S, Raymond HF, McFarland W. The impact of discrimination on the mental health of trans∗female youth and the protective effect of parental support. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(10):2203–2211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1409-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Vries ALC, McGuire JK, Steensma TD, Wagenaar EC, Doreleijers TAH, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Young adult psychological outcome after puberty suppression and gender reassignment. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):696–704. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-2958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al.. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3869–3903. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2017-01658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al.. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. Int J Transgend. 2012;13(4):165–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2011.700873 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vance SR Jr, Halpern-Felsher BL, Rosenthal SM. Health care providers’ comfort with and barriers to care of transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(2):251–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vance SR, Ehrensaft D, Rosenthal SM. Psychological and medical care of gender nonconforming youth. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):1184–1192. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-0772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spack NP. Management of transgenderism. JAMA. 2013;309(5):478–484. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.165234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shumer DE, Spack NP.. Current management of gender identity disorder in childhood and adolescence: guidelines, barriers and areas of controversy. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20(1):69–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/MED.0b013e32835c711e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olson J, Forbes C, Belzer M. Management of the transgender adolescent. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(2):171–176. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee PA, Houk CP.. Evaluation and management of children and adolescents with gender identification and transgender disorders. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2013;25(4):521–527. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0b013e328362800e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopez X, Stewart S, Jacobson-Dickman E. Approach to children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. Pediatr Rev. 2016;37(3):89–98. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.2015-0032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guss C, Shumer D, Katz-Wise SL. Transgender and gender nonconforming adolescent care: psychosocial and medical considerations. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27(4):421–426. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caring for transgender adolescent patients [PowerPoint presentation]. In: ARSHEP presentations & case videos. Physicians for Reproductive Health website. https://prh.org/arshep-ppts/#lgbtq-essentials. Updated January 2, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gender Spectrum website. https://www.genderspectrum.org/. Accessed June 6, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall A, Pickle S, Lawlis S. Transgender medicine curriculum: integration into an organ system–based preclinical program. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10536 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rafferty J; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Adolescence, Section on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health and Wellness. Ensuring comprehensive care and support for transgender and gender-diverse children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4):e20182162 https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vance SR Jr, Deutsch MB, Rosenthal SM, Buckelew SM. Enhancing pediatric trainees’ and students’ knowledge in providing care to transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60(4):425–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vance SR Jr, Lasofsky B, Ozer E, Buckelew SM. Teaching paediatric transgender care. Clin Teach. 2018;15(3):214–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarrett BA, Corbet AL, Gardner IH, Weinand JD, Peitzmeier SM. Chest binding and care seeking among transmasculine adults: a cross-sectional study. Transgend Health. 2018;3(1):170–178. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2018.0017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Killermann S. The Genderbread Person version 4. It's Pronounced Metrosexual website. https://www.itspronouncedmetrosexual.com/2018/10/the-genderbread-person-v4/. Accessed November 18, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. Guidelines for Care of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients. San Francisco, CA: Gay and Lesbian Medical Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adolescent sexual health. American Academy of Pediatrics website. https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/adolescent-sexual-health/Pages/LGBTQ-Youth.aspx. Accessed November 18, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sexual and reproductive health: defining sexual health. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/sexual_health/sh_definitions/en/. Accessed November 18, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein DA, Goldering JM, Adelman WP. HEEADSSS 3.0: the psychosocial interview for adolescents updated for a new century fueled by media. Contemp Pediatr. 2014;31(1):16–28.26185795 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- Module 1 Construct of Gender.mp4

- Module 2 Gender History.mp4

- Module 3 Psychosocial History.mp4

- Module 4 Physical Examination.mp4

- Module 5 Assessment and Psychosocial Plan.mp4

- Module 6 Medical Plan.mp4

- Question Prompts for Modules 1-3.docx

- Entire Curriculum Retrospective Pre- and Postassessment.docx

- Preassessment Online Module Only.docx

- Postassessment Online Module Only.docx

- Answer Key for Objective Knowledge Questions.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.