Problem

On March 17, 2020, the Association of American Medical Colleges recommended the suspension of all direct patient contact responsibilities for medical students because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given this change, medical students nationwide had to grapple with how and where they could fill the evolving needs of their schools’ affiliated clinical sites, physicians, and patients and the community.

Approach

At Harvard Medical School (HMS), student leaders created a COVID-19 Medical Student Response Team to: (1) develop a student-led organizational structure that would optimize students’ ability to efficiently mobilize interested peers in the COVID-19 response, both clinically and in the community, in a strategic, safe, smart, and resource-conscious way; and (2) serve as a liaison with the administration and hospital leaders to identify evolving needs and rapidly engage students in those efforts.

Outcomes

Within a week of its inception, the COVID-19 Medical Student Response Team had more than 500 medical student volunteers from HMS and had shared the organizational framework of the response team with multiple medical schools across the country. The HMS student volunteers joined any of the 4 virtual committees to complete this work: Education for the Medical Community, Education for the Broader Community, Activism for Clinical Support, and Community Activism.

Next Steps

The COVID-19 Medical Student Response Team helped to quickly mobilize hundreds of students and has been integrated into HMS’s daily workflow. It may serve as a useful model for other schools and hospitals seeking medical student assistance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Next steps include expanding the initiative further, working with the leaders of response teams at other medical schools to coordinate efforts, and identifying new areas of need at local hospitals and within nearby communities that might benefit from medical student involvement as the pandemic evolves.

Problem

The worst is, yes, ahead for us. It is how we respond to that challenge that’s going to determine what the ultimate endpoint is going to be.1

These words, proclaimed on March 15, 2020, by Dr. Anthony Fauci, the longtime director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, were a call to action in today’s COVID-19 reality. The medical profession is facing one of its greatest challenges and needs to act. This call fueled a fire that was rapidly building at our institution, Harvard Medical School (HMS), among clerkship and postclerkship medical students, for whom clinical responsibilities fundamentally changed when we were pulled from all direct patient care–related duties on March 13. As student leaders at HMS, we knew medical students could still play a role in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Approach

On March 15, our group of student leaders formed the COVID-19 Medical Student Response Team (https://covidstudentresponse.org, send direct inquiries to hmscovid19studentresponse@gmail.com), with the support of the HMS administration. The underlying motivation and goals of this team were to: (1) develop a student-led organizational structure that would optimize students’ ability to efficiently mobilize interested peers in the COVID-19 response, both clinically and in the community, in a strategic, safe, smart, and resource-conscious way; and (2) serve as a liaison with the administration and hospital leaders to identify evolving needs and rapidly engage students in those efforts. Advanced medical students have valuable skills and clinical knowledge that can be appropriately used to help physicians, staff, and ultimately patients. While physicians are working on the frontlines caring for patients, student leaders can organize the medical student workforce and, with hospital administration, determine where this untapped but skilled group can best contribute.

Recommendations from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) regarding the role of medical students in direct patient care were rapidly evolving at the time we formed our response team. While the AAMC initially endorsed medical students’ continued involvement in clinical settings, on March 17, they released the following statement: “Starting immediately, the AAMC strongly supports our member medical schools in placing, at minimum, a two-week suspension on their medical students’ participation in any activities that involve patient contact.”2

Discussions with fellow students who had been in clinical settings as COVID-19 pressures mounted made it clear why many medical students may endorse this position. Any expectation to continue “business as usual” in terms of undergraduate medical education on the wards might cause more harm than good. As trainees, we have a certain degree of medical and clinical experience and skill that could be beneficial to patients. At the same time, we are limited in what we can do as trainees. Elective surgical cases were cancelled, clinics were closed, personal protective equipment was limited, and the clinical workflow was changing. Pausing to rethink our role as medical trainees would be prudent. The last thing we wanted to do was endanger sick patients and further burden those already working overtime in the hospital.

Outcomes

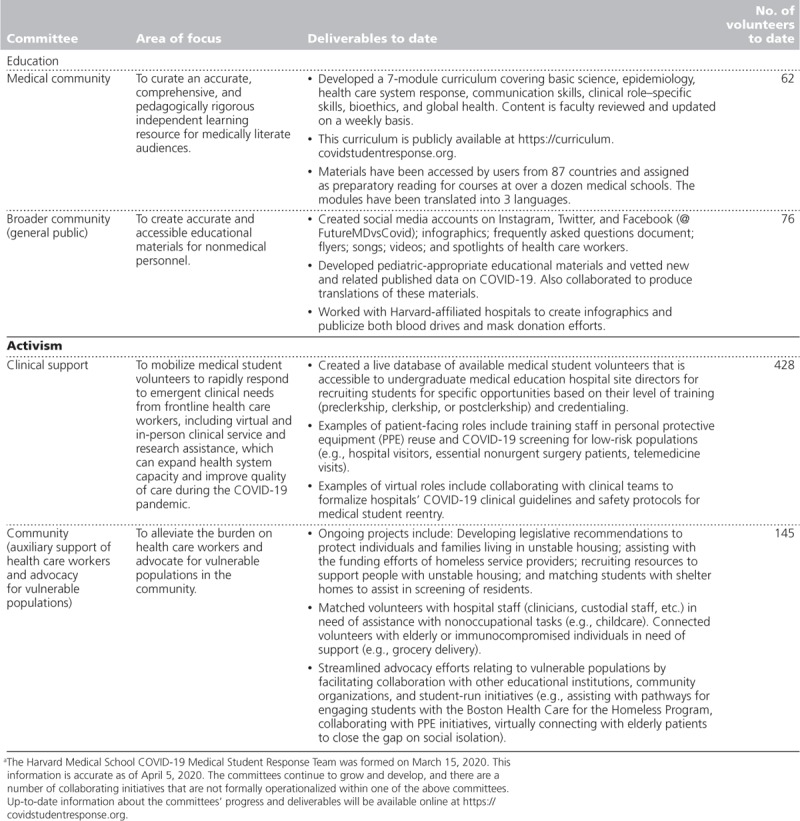

Our COVID-19 Medical Student Response Team identified areas of need relating to education on COVID-19 and the activism in which medical students at all levels of training were either already taking part or potentially could have an active and impactful role. These areas translated into the establishment of 4 virtual committees: Education for the Medical Community, Education for the Broader Community, Activism for Clinical Support, and Community Activism. The 2 education committees create and disseminate materials on COVID-19 for medical providers and nonmedical personnel. The 2 activism committees mobilize student volunteers to alleviate burdens on health care workers both in the hospital and at home. Table 1 includes more details about the work of these committees to date, including the creation of a COVID-19 curriculum and other educational materials as well as a public database of available volunteers and opportunities to get involved. From the start, we decided that the response team would not focus on real-time challenges facing students, such as virtual coursework learning environments, housing, and graduation; these concerns would be addressed by the student council and members of the HMS Medical Education Representative program, which was formed in 2015 to foster student–faculty partnerships to improve the educational curriculum.3

Table 1.

Organization and Progress of the COVID-19 Medical Student Response Team, Harvard Medical School, 2020a

We recruited team leaders for each of the committees to refine the scope, goals, and potential deliverables of the groups. By March 17, we had opened up the committees to the entire HMS student body. Students were invited to volunteer for any of the 4 committees or to share their input on how to further improve this work. Within 5 days, more than 500 medical students across HMS alone had volunteered to participate. Initially, the leadership team (composed of the 3 response team coleaders [D.S., S.G., K.W.S.] and each of the committee leaders [D.B., P.E., N.J., M.K., N.U., D.V., K.V.]) met on a daily basis via videoconference (Zoom, Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, California) to discuss progress, barriers, needs for administration guidance, and opportunities for growth. The committees then established their own internal forms of communication and daily meeting schedules. Currently, the leadership team conducts a weekly strategic review to identify key processes that need to be established, identify synergies between committees, and adapt processes as the crisis unfolds. Committees use GroupMe (Microsoft, New York, New York), a group text messaging service, to simplify communications. GroupMe allows for intercommittee collaboration and discussion, sharing of key COVID-19 resources, and distribution of other updates relevant to the group.

Even as our response team took shape, we learned of other medical school initiatives in the preliminary stages and sought ways to collaborate and broaden our collective impact. Through peer discussions, we spoke about our initiative with medical student leaders from 32 schools across the United States who were mobilizing their student bodies in a similar manner. Even faculty and student leaders from other graduate schools across our institution as well as others from external programs inquired about how their students, with no medical training, could engage with our committees. For instance, many of these individuals have joined our volunteer pool to provide emergency childcare, assist with grocery pickup, or fill other urgent needs for frontline health care staff.

What we had already sensed locally at HMS and nationally became even more apparent during these broader discussions: Medical students were strongly and intrinsically motivated to help. Trainees, especially those in their postclerkship period, were well-positioned to practically assist with the COVID-19 response, given our clinical and scientific knowledge, access to hospital electronic health records for patient care, and most importantly, time to contribute in ways that faculty cannot during this public health emergency.

Our response team’s efforts to engage medical students in the COVID-19 response had other advantages as well. Many advanced clerkship and postclerkship medical students, like us, who had been turned away from clinical responsibilities felt powerless. Yet, research has shown that these feelings can be countered through collective action toward a common goal.4 Enthusiasm and organized movement toward such a goal can foster a sense of empowerment, purpose, and connection. This, and the fact that we as students can provide unique and rare assistance, fueled a growing desire within our trainee community to organize and act. Though we are not yet fully trained physicians, we can collectively leverage the training we have had to serve where we can be most valuable, supporting our frontline physicians and, ultimately, patients.

Next Steps

Already, the COVID-19 Medical Student Response Team has accomplished a range of deliverables across its 4 committees and functions as the primary organization coordinating medical student involvement across the 5 main hospitals affiliated with HMS that support clerkship students (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston Children’s Hospital, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Cambridge Health Alliance, and Massachusetts General Hospital). The leadership team provides nearly daily verbal and written updates to the HMS administration and student body and will continue to track a range of committee process measures, including the number of users accessing the curriculum, students volunteering at clinical sites, connections made for supporting childcare, and social media followers. Yet, our primary motivation and the outcome that matters most are preventing unnecessary suffering from COVID-19.

For medical schools across the country with a similar sentiment among their student body, we suggest developing a team akin to ours that is open to all medical students in a given area (for instance, all within the same city). To reduce duplication of efforts and optimize our impact as students, leaders from each of these teams should convene weekly. Structured collaboration between medical schools would optimize students’ impact, particularly relating to the dissemination of information and materials on COVID-19.

If they have not done so already, we strongly recommend that medical school and hospital administrators identify individuals from their faculty or staff to liaise with their medical student team. HMS identified an individual from each affiliated hospital and, within a week of the response team’s inception, these hospital liaisons were tapping into our student network of volunteers. In addition, our clinical support activism committee leaders regularly meet virtually with these liaisons and associated administrative staff to strategize ways in which students might best fulfill the constantly evolving needs of physicians and staff at the different hospitals. We also have been heartened to learn of the numerous medical student response groups emerging across the country and have expanded our leadership team to work on initiatives that will help us to formalize collaborations with these other groups moving forward.

COVID-19 has left clerkship and postclerkship medical students unexpectedly with no traditional clinical duties, but all hands are needed to confront this growing threat. Despite our limitations as trainees, medical students still have a duty to contribute what we can to response efforts. We can actively serve our patients and our community in one capacity or another, whether by learning the science of COVID-19, offering guidance about social distancing to family and friends, engaging in activism for the most vulnerable who are being affected, filling needed roles to augment clinical capacity, or lessening the burden on frontline health care workers. We are ready to rise to the challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic, and our medical student response team is one way that we are doing just that.

Acknowledgments:

First and foremost, the authors would like to thank Dr. George Daley, Dean of Harvard Medical School, Dr. Edward Hundert, Dean for Medical Education, and Dr. Fidencio Saldana, Dean for Students, for their support and leadership with the COVID-19 Medical Student Response Team. The authors also would like to acknowledge those individuals who were present at the response team’s inception and/or have collaborating initiatives: Troy Amen, Grace Baldwin, Pooja Chandrashekar, Josie Fisher, Andrew Foley, Gwendolyn Lee, Benjamin Levy, Vartan Pahalyants, and Hema Pingali. The authors would like to extend their deepest gratitude to all the medical student volunteers who have worked tirelessly through these committees. This work would not be possible without them. See https://covidstudentresponse.org for a complete list of the medical students involved. Finally, the authors would like to thank Dr. David S. Jones and Dr. Edward Hundert, professors at Harvard Medical School, for their valuable advice on this manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding/Support: None reported.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

References

- 1.Kendall B, Day C, Leary A. Wall Street Journal; https://www.wsj.com/articles/fauci-urges-americans-to-stay-home-amid-coronavirus-11584284229. Published March 15,2020. Accessed April 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association of American Medical Colleges. Guidance on Medical Students’ Clinical Participation: Effective Immediately. https://lcme.org/wp-content/uploads/filebase/March-17-2020-Guidance-on-Mediical-Students-Clinical-Participation.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2020

- 3.Scott KW, Callahan DG, Chen JJ, et al. Fostering student-faculty partnerships for continuous curricular improvement in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94:996–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenstein L. To fight burnout, organize. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:509–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]