Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 crisis is a global pandemic of a novel infectious disease with far-ranging public health implications. With regard to cardiac electrophysiology (EP) services, we discuss the “real-world” challenges and solutions that have been essential for efficient and successful (1) ramping down of standard clinical practice patterns and (2) pivoting of workflow processes to meet the demands of this pandemic. The aims of these recommendations are to outline: (1) essential practical steps to approaching procedures, as well as outpatient and inpatient care of EP patients, with relevant examples, (2) successful strategies to minimize exposure risk to patients and clinical staff while also balancing resource utilization, (3) challenges related to redeployment and restructuring of clinical and support staff, and (4) considerations regarding continued collaboration with clinical and administrative colleagues to implement these changes. While process changes will vary across practices and hospital systems, we believe that these experiences from 4 different EP sections in a large New York City hospital network currently based in the global epicenter of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic will prove useful for other EP practices adapting their own practices in preparation for local surges.

Keywords: administration, coronavirus, COVID-19, pandemic, restructuring

“So, to the extent people watch their nightly news in Kansas and say, ‘Well, this is a New York problem,’ that’s not what these numbers say. It says it’s a New York problem today. Tomorrow, it’s a Kansas problem and a Texas problem and a New Mexico problem.”

—New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo, April 1, 2020.

INTRODUCTION

In March 2020, New York City became the new global epicenter of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. The exponentially rising New York City COVID-19 caseload and the preceding experiences in China, Italy, and Washington state demonstrated a stark reminder that a catastrophe like a pandemic may potentially overwhelm even the most advanced health systems. In 2009, during the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic, the Institute of Medicine detailed “crisis standards of care,” defined as a “substantial change in the usual health care operations and the level of care it is possible to deliver… justified by specific circumstances and… in recognition that crisis operations will be in effect for a sustained period.”1

All medical departments in New York City instituted their respective crisis and contingency protocols while trying to maintain the highest possible quality of care for the upcoming months. In Lombardy, Italy, the unique organizational issues of an interventional cardiology department in treating patients during the pandemic crisis were recently described, including recommendations for patient risk-stratification, cardiologist team reassignment, interhospital collaboration, and safety considerations.2 With regard to electrophysiology (EP) services, the surge in COVID-19 activity in New York City presented multiple challenges, requiring considerable “ramp down” and structural reorganization specific to the field of EP, as many services do not remain idle during this time period. We describe the changes in usual operations implemented in our 4 dedicated EP laboratory sections across the NewYork-Presbyterian (NYP) enterprise (i.e., Columbia University Irving Medical Center, Weill Cornell Medical Center, Queens, and Brooklyn Methodist Hospital).

Our collective experience across the 4 NYP EP services may be representative of the rapid institutional changes that are required during a pandemic or national disaster. Therefore, we believe that these details of “how to ramp down” can serve as a practical guide and be of particular interest to other EP sections as rapidly rising cases of COVID-19 threaten other parts of the country. We additionally relay a handful of case scenarios from our experience that point out examples for how EP sections can prepare their policies and procedures (with prior CUIMC Institutional Review Board approval).

Step 1: Acknowledge That a Public Health Crisis Has Arrived

Understanding the potential scope of the COVID-19 problem has been challenging at all levels of policy-making, including national, state, and local, and within individual organizations. In the early days of March 2020, there was considerable debate across the country, including over social media, about the scope of scaling back and reprioritization of services, including whether nonurgent EP procedures should be postponed. Although the answer to these questions seems obvious in retrospect, the timing of when to begin canceling cases has often been staggered and made at the local level.

To offer an example of the global sense of how the COVID-19 crisis has impacted our hospital network, as of the writing of this article on April 16, 2020, the entire NYPH medical system (which includes more than these 4 hospitals) reported 2317 COVID+ inpatients (598 at Columbia, 471 at Weill Cornell, 424 at Queens, 326 at Brooklyn Methodist, and remainder at affiliate hospitals); a total of 743 of these patients were located in ICUs given the severity of their illnesses. To meet these demands, one goal of the network has been to increase intensive care unit (ICU) bed capacity from a baseline of approximately 400 ICU beds to over 1000 ICU beds, a herculean task requiring a complete transformation of all hospital resources, including staff duties and physical plant. We describe the pivoting of operations within the context of 3 broad categories of reorganization, including (1) procedure-related and inpatient care, (2) outpatient care, and (3) administrative restructuring.

PROCEDURE-RELATED AND INPATIENT CARE

Step 2: Decide What Urgent EP Procedures Are Possible

We follow the recently consolidated HRS/ACC/AHA COVID-19 practice guidance.3 Such a rapid and complete ramp down requires effort to communicate with and reassure scheduled patients that the procedure can be safely postponed. In reality, a decision about procedure triage is not necessarily a black and white one but includes shades of gray. For example:

We adopted a policy to perform procedures only in patients felt to have a likelihood of significant clinical deterioration within a short period of time, which has varied, depending on local availability of ancillary staff and PPE resources, from between 48 hours to 1–2 weeks.

All other prescheduled elective cases have been canceled without a reschedule date.

Direct admissions or transfers are very limited, given the surge of ED patients requiring admission.

As procedural areas have been converted into ICUs, the availability of procedural space for EP procedures must be carefully discussed with hospital leadership.

The EP procedural volume has decreased along with the overall non-COVID+ volume in the hospital. In our experience, lab volume has decreased by 80%–95% across all sites. The majority of procedures performed are implantable devices, predominantly permanent pacemakers (PPMs) for high-grade atrioventricular block (AVB).

Across our institutions, to date, only one ablation has been performed, which occurred just before the start of the patient surge. One device system extraction due to recalcitrant sepsis with a visible lead vegetation was performed. Patients with ventricular tachycardia (VT) have been to date managed medically, usually with amiodarone (and in many cases as outpatients with frequent follow-up, as described below). As the time spent operating under these conditions increases, we anticipate the increased possibility that patients will breakthrough medical therapy and require ablation therapy. In short, if the case is not urgent, it is not done.

Step 3: Consider How to Optimize Use of Staff to Minimize Exposure During Procedures While Preserving PPEs

Workflows that have been ingrained for years all need to be reconsidered. For example, we maintain one operational EP lab at each center, sometimes shared with cath lab colleagues. In order to preserve PPE, and because staff, including specialized scrub technicians and nurses, have been “redeployed” to other units, we function by the mantra, “If it can be done by one person, then it should be done by one person.” Cases are performed by a single attending. A surgical mask is placed on all patients, and if a patient’s respiratory status is in question or tenuous before a procedure, then consideration of endotracheal intubation is discussed before patient transport to minimize aerosolization risk in the lab. N95 masks are used by operating physicians for all cases. As many anesthesia teams have been redeployed to assist with central lines and intubations, conscious sedation administered by the EP MD (with backup anesthesia services) is utilized if felt to be a reasonable option that does not compromise patient safety.

Step 4: Coordinate With Your EP Group, Other Clinical Sections, and EP Sections From Network Hospitals

Frequent updates are required for appropriate communication in the era of social distancing, including updates regarding staff who are ill and not able to work. For example:

Daily morning meetings, conducted by videoconference, have allowed for the 11 EP attendings, as well as nurse practitioners and administrative staff, in the Columbia practice to remain in active communication. This venue allows for discussion of challenging cases, deliberation of how to message recommendations in a unified way (e.g., regarding COVID-related consultation questions), schedule shared responsibilities, and contingency plan. Smaller EP groups remain in communication via telephone.

Preplanning and coordination of urgent procedures with colleagues of other disciplines, including anesthesia, nursing, blood bank, backup surgery (the latter 2 for urgent extractions), allows for these representatives to deploy already stretched staff/resources and expedite throughput of patients.

Discussion and coordination with colleagues in other hospitals allow for “reality checks” regarding local practice patterns, and brainstorming of strategies to address shared challenges.

The following is a summary of significant lab practice changes, specific cases, and “pearls” from our collective experience:

One area of deliberation has involved the timing of stable pacemaker-dependent outpatients with devices at elective replacement interval (ERI). As there is variation between companies in battery longevity and case reports of rapid unexpected battery depletion after ERI4 and remote monitoring interrogations may further deplete the battery, we recommend performing a generator change within 1 month after the onset ERI in these patients, which we believe is in keeping with the HRS/ACC/AHA guidelines which classify these cases as non-elective/urgent.3 A list of patients monitored at home with devices around ERI should be maintained, so accurate contact information is important.

We have performed implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) placement on stable outpatients wearing an external ICD and awaiting a permanent implantable device or inpatients with multiple episodes of nonsustained VT and systolic dysfunction (HRS/ACC/AHA classification as semi-urgent3). Device implantations are discharged the same day, when feasible, and ideally with remote monitoring capability.

In the case of a COVID-negative patient presenting to the hospital in high-grade AVB, we arranged to perform an expedited same-day PPM (including lab team mobilization on weekends). Similarly, we are prepared to perform same day and secondary prevention ICD placement in heart failure patients with VT.

In the case of an unstable transcatheter aortic valve replacement at high-risk for AVB, we coordinated with the structural valve team to be on-site and perform a PPM immediately following valve deployment in the same operating room if the patient developed irreversible AVB, facilitating same-day discharge. Coordination between cath and EP nursing (if not cross-trained) must be considered, as nursing staff may have been redeployed to other units.

For atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response refractory to medical therapy requiring cardioversion, computed tomography angiography scans are used (whenever possible) to rule-out left atrial appendage thrombi instead of transesophageal echocardiograms to minimize aerosolized exposure to transesophageal echocardiograms and anesthesia staff. Intracardiac echocardiogram to assess for thrombus has also been considered for appropriate candidates.

Attempt to perform device interrogations remotely. It is important to coordinate as early as possible with all device companies, as well as with clinical colleagues in the emergency department (ED), to establish remote monitoring capability in the ED and even ICUs. Indications for interrogation are limited to frank syncope, documented device malfunction, recurrent ICD shocks, need for a program change, and rule-out atrial fibrillation/flutter + cryptogenic stroke.

We have rotated device representative assistance in an effort to minimize exposure risk.

For hospitals that do not routinely perform device implantations on weekends, implement a strategy of opening the EP lab during this time period to implant a PPM in AVB patients and expedite patient flow/free up ICU bed space.

Urgent device implants have been performed while tolerating higher than usual international normalized ratios (e.g., international normalized ratio > 3.0), when benefit:risk ratio deemed appropriate.

Some patients have had procedures, including generator changes and direct current cardioversions, performed outside the metro New York area to minimize exposure risk and preserve PPE and other hospital resources.

Step 5: Strategize How to Manage Inpatient EP Consultations

Inpatient consult volume has diminished to approximately 1/3 of its baseline during the pandemic. Consultations are evaluated by one person to minimize exposure. Based on guidance regarding emergency healthcare provision during this crisis in the state of New York, if in-person consultation is not deemed to be necessary for diagnosis and treatment, then provider discretion is used to forego such potential exposure. Careful attention to communicate case presentations and recommendations thoroughly among consulting teams, consultants, and patients is paramount. Real-world applications of these points include:

Consults are performed remotely if possible via the electronic medical record, including Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant texts of electrocardiograms (ECGs) and telemetry strips sent to the consultant via the media section of the EMR. Some centers have remote access to inpatient telemetry. Telephone consultation with COVID+ inpatients (when possible), as well as discussions over the phone with family/friends (who are not able to remain with patients during this time period), has been utilized.

In the case of COVID-positive patients, we use telemetry to determine the rhythm and measure the QTc, preferably with lead II. COVID-19 related consults have included atrial fibrillation, atrial tachycardia, sinus arrest, accelerated idioventricular rhythm and VT in patients with myocarditis, and QTc prolongation with torsades.

Physician protection is paramount, and refresher web-based videos of donning and doffing were reviewed by all clinical staff.

OUTPATIENT CARE

Step 6: Set Up Telehealth and Address Its Challenges

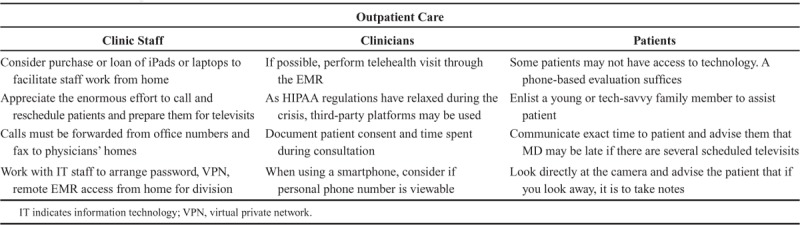

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine across the country advanced dramatically within 1 week. Guided in part by changes in billing restrictions regarding televisits, as well as HIPAA restrictions, we transitioned nearly all patients to telehealth visits using videoconferencing capability native to electronic medical record system or using third-party video applications.5 A summary of outpatient challenges, considerations, and recommendations is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Challenges, Responsibilities, and Considerations for Clinic Staff, Clinicians, and Patients During the Transition to Telehealth Visits During the COVID-19 Pandemic

For front-end staff: To facilitate remote “work from home” EP, some challenges and solutions have included:

For staff without access to appropriate computer equipment, the division purchased and loaned iPads for some staff at one hospital to perform televisits and loaned laptop computers for other staff who needed to access the electronic record system.

Recognize the increased efforts required to (1) contact patients to shift previously scheduled outpatient in-person visits and device checks to televisits, (2) remind patients not to come to clinic in-person, (3) obtain appropriate training to accommodate this change in workflow, (4) have staff guide patients through the process of being televisit-ready. Additional staff (e.g., medical assistants) are often required to be deployed to accomplish these tasks.

Coordination of call-forwarding of office numbers and fax management to staff now working from home.

Brainstorming flexible work solutions for those staff now with children at home from school or ill relatives needed to be addressed. Our network has been heavily involved in coordinating and communicating options to staff.

Working with informational technology (IT) staff (who themselves required additional support due to increased demand) to ensure adequate password access, virtual private network (VPN) access, and access to all required remote systems from home.

While supporting flexibility and addressing barriers to home-based work, reinforcing the need for prioritization of work-related commitments while based in a home environment.

Reaching consensus regarding changes in workflow patterns, including televisits, that are occurring due to the COVID-19 crisis.

Interestingly, whereas in the past, patients were resistant to setting up telemedicine, we have found that patients are now amenable to this option and have expressed satisfaction with reduced travel time and peace of mind regarding social distancing.

For clinical providers performing televisits, potential challenges and solutions of rapid adaptation to telehealth have included:

Review if and how it is possible to perform televisits through the electronic medical record system, if possible.

In this crisis setting with relaxed HIPAA regulations, other third-party applications have also been utilized for televisits, and specific accounts have been opened for each attending, with a discussion of individuals’ preferences. All video conference visits have been deemed eligible for reimbursement by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, provided that documentation confirms the patient consented to telemedicine and specifies the time spent in consultation. Documentation of televisit type is noted in case other modalities, such as telephone visits, are deemed acceptable for billing.

If smartphones are used, consider whether personal phone number is viewable while using these different modalities.

For patients, the following potential challenges and solutions have included:

Each patient’s televisit capabilities must be assessed. Some patients may not be technologically adept, or not have access to a smartphone, laptop, WiFi, or e-mail. Although a telephone-based evaluation is not reimbursed at this time, we have found it is still an effective way to provide care to anxious patients who are unable to access telehealth in other ways. We have found that the following basic telemedicine “pearls” help smoothen the experience for patient and caregiver:

Communicate an exact time when the patient should log in to prevent miscommunication. Remind patients that providers may be late to calls, and to please allow for a certain time period to lapse before logging off.

Consider enlisting family members to assist patients requiring technical help to initiate or complete a visit.

When speaking to the patient, look directly into the camera on your computer to simulate eye contact. Explain to the patient that if you look away, it is to take notes.

Ensure appropriate lighting is present in the physician’s home “office” space.

Patients transmitting remotely who were coming for an annual visit were rescheduled for a time in the distant future with continued remote monitoring; patients who had remote monitoring-capable devices but were not enrolled were called by an MD or NP and encouraged to enroll, and a remote monitor was sent to them; patients with devices incapable of remote monitoring were scheduled for an outpatient session in the future, with timing dependent on prior history, including estimation of battery life.

Postprocedure “wound care” follow-up has been accomplished through a dedicated, staffed e-mail address where patients may send photos of their wound site. Rapid provision and in-servicing in the use of remote home interrogators is imperative, as patients can send remote downloads from their home monitors to serve as postprocedure interrogations.

Apple watch, Kardia recordings, and mailed Holters and patch monitors have been used to assess for arrhythmias and to follow the QT interval.6 Remote ECG transmissions have been useful to document exacerbations of arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation, in otherwise stable outpatients, as well as provide reassurance to those patients with heightened anxiety in general during the COVID-19 crisis.

When higher-risk patients are seen in person, the EP administrative staff is informed. A screening for COVID-19 symptoms must be performed before the visit. If possible, efforts should be made to have the consult at a less utilized “off-site” away from the hospital. At least one hospital has transitioned all outpatient visits off-site, as this option was felt to minimize exposure risk to outpatients (versus a facility with a high percentage of COVID+ patients).

Examples of patients who had in-person appointments during the COVID-19 surge in our system include assessments for patients with a concern for radiation skin injury after prolonged biventricular device placement, poor wound-healing in a device patient that required cleaning and adhesive, a thorough device interrogation in a PPM-dependent patient with a question of RV lead integrity, and an ICD interrogation for a patient with a lead conduction fracture and increasing episodic noise.

Lastly, it is an enormous challenge to manage patients who are shocked by their ICD at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. In our experience, due to patient reluctance and/or limited availability of ED and inpatient resources, cases ordinarily managed with ED visits/admissions or direct admissions may not be possible. To date, of 4 patients with multiple ICD shocks due to VT, all were medically managed after presenting to the ED for assessment of vitals and baseline laboratory testing and released home with careful follow-up, without inpatient admission. Examples include:

A patient with history of familial dilated cardiomyopathy and a subcutaneous ICD received 3 successive shocks for monomorphic VT. He was advised to take an extra dose of carvedilol and was transported by ambulance to a local ED, where he received an intravenous amiodarone load and was discharged on oral amiodarone 24 hours later without recurrent events, with plan to follow-up at a later date, as medical resources allow.

A patient with history of ischemic cardiomyopathy and a single lead ICD was brought to a network hospital site after receiving 7 shocks for monomorphic VT in the ventricular fibrillation zone in the setting of medication noncompliance. He received intravenous amiodarone 150 mg bolus and 6 hours of an infusion at 1 mg/min before being discharged on metoprolol and oral amiodarone load.

ADMINISTRATIVE RESTRUCTURING

Step 7: Plan for Shifting Responsibilities as Staff Are Redeployed

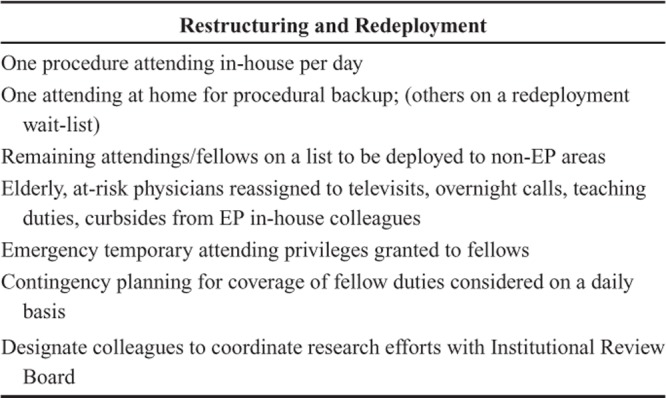

Paralleling the procedural and outpatient experience, day-to-day life of the administrative aspects of the inpatient EP services have changed completely during the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Key Points When Considering Administrative Restructuring and Both External and Internal Redeployment

MD scheduling: Given the dramatic decrease in EP-centered patient volume, each on-call physician is involved in direct patient care at each hospital. As mentioned above, one attending performs procedures alone, with a backup physician available for assistance if needed. This system allowed for the flexibility of physician staff to continue to attend to their prescheduled responsibilities, including outpatient telehealth visits and inpatient rounding within the Cardiology division, and to record staff available for possible redeployment.

Contingency Planning for Deployment and Illness: Continuous flexibility regarding the rotation of MD staff should be maintained to adjust for physicians who fall ill or are redeployed in other areas of the hospital system, including ready availability of staff.7

Internal Redeployment: Providers and staff (physicians included) with patient-facing duties who have relevant medical comorbidities, and/or older age have been redeployed to nonpatient-facing duties,8 including

-

-

Covering inpatient as well as outpatient remote televisits, including for colleagues who have been redeployed

-

-

Talking to patient families over the phone who are unable to be physically with their loved ones in the hospital

-

-

Fielding overnight and weekend calls to relieve inpatient-based colleagues

-

-

Curbside consultations with junior EP staff members

-

-

Continuing teaching duties of trainees when appropriate

-

-

Administrative scheduling (i.e., to see patients remotely, talk with patients’ families).

Practically, we have created a schedule to delegate and track specific responsibilities for each MD that is accessible through a shared EP drive or the internet, with the goals of transparency and equitable balance of responsibilities. This has allowed for regular updating, including

One procedure attending in-house per day for procedures, clinic or floor work

One attending at home for procedural backup

Remaining attendings and fellows on a list to be deployed to non-EP areas (e.g., ICU/expanding ICD footprints or clinic as needed due to the expansion of ICU units, hospitalists, and general medicine services).

Contingency planning for fellows and non-MD staff: Other staff members’ responsibilities have also changed considerably, often directed by hospital leadership, including department chiefs. These include:

Emergency temporary attending privileges have been granted to fellows in their board certified/eligible fields.

Nurse practitioners and physician-assistants have been transitioned to outpatient remote practices and also redeployed to surging EDs, cough/fever clinics, and ICUs.

Contingency planning for coverage of fellow duties and nonclinical staff is considered on a daily basis.

Satellite offices have been consolidated to minimize exposure risk and allow for redeployment of staff to other needed areas.

Each deployment is managed centrally in conjunction with the Cardiology and Medicine divisions, depending on the particular needs of the hospital, and staff has also been deployed to hospitals within the network, as emergency privileges for all clinicians within the network hospitals were authorized. Further staff responsibilities include designating colleagues to coordinate research efforts with Institutional Review Board and other departments on topics of more urgent COVID-related interest (e.g., QTc in the setting of COVID-19 treatment, obtaining 7-lead ECGs off telemetry in units since unable to perform frequent 12-lead ECGs on COVID-19 patients).

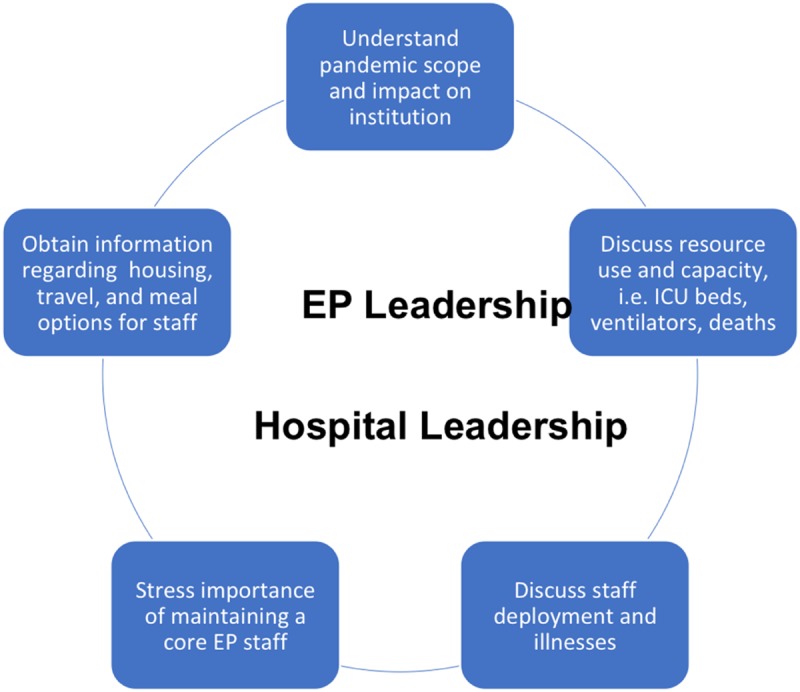

Step 8: Communicate With Hospital Leadership Regularly

Lastly, but certainly not least in importance, is the need for regular, 2-way communication between sections and hospital leadership (Fig.1). For larger EP practices, we recommend that at least one staff member directly communicates with hospital and clinical division leaders each day for several reasons. These communications allow EP staff to:

Figure 1.

Discussion points for regular daily communication between the hospital and EP leadership. It is important to troubleshoot clinical and administrative challenges and understand the broader balance of hospital needs with EP division resources during dynamic workflow changes.

Understand and appreciate the broader institutional picture, including the scope of the pandemic and its impact on the network

Discuss resource use and capacity

Discuss staff allocation, challenges, and illnesses

Troubleshoot daily clinical and administrative challenges

Provide and receive feedback in the setting of altered workflows

Convey that EP practices are relatively smaller compared with other services, and deployment needs of the hospital should be balanced with the need for availability of a core number of EP staff with specialized skills necessary to perform urgent/emergent EP procedures

Coordinate staffing changes regarding ill/exposed staff members from Workforce Health & Safety and Infection Prevention & Control departments.

Obtain information regarding possible housing, travel, and meal options for staff, including (1) the provision of temporary housing while working and unable to travel back-and-forth, or desiring of isolating from loved ones at home, (2) reimbursement of parking expenses for staff who normally travel without vehicles, (3) shuttle schedules for urban commuters, and (4) meal provisions while at work. These resources have been provided to us by the network system, including temporary housing provision for over 1800 staff members.

All this information is relayed during a daily EP section videoconference. The point-person is responsible for communicating directly to hospital/clinical leadership.

Practically, our shared morning workflow proceeds as follows:

Holding a regularly scheduled video conference among physicians and ancillary staff to discuss health check-ins, hospital capacity updates, and procedural and ethical discussions. An agenda is circulated before each meeting, and minutes are kept. Depending on local staffing and workflow, frequency of meetings has varied from daily to a few times per week.

Video conferences allow for the continuation of fellow education conferences, which are performed remotely with PowerPoint lectures and electrogram-based “quizzes.”

Solicit questions, suggestions, and feedback, including reviewing the importance of appropriate PPE use, as well as experiences and best-practice tips for donning and doffing PPE.

We find that these daily meetings also present a much-needed opportunity to decompress and maintain positive morale among staff, as more deliberate communication with colleagues is necessary to overcome the physical barriers to “curbside encounters” imposed by social distancing. Striving to maintain regularly scheduled weekly electrogram conferences and case reviews helps to maintain a sense of camaraderie and “normalcy” during these challenging times.

CONCLUSIONS

During the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City, restructuring in the form of multiple “ramp down” and pivot modifications have been rapidly applied to the EP services across the NYPH hospital system, resulting in deployment of EP resources in a streamlined but not idle fashion. It is obviously better to prepare in advance for such ramp down, with contingency protocols in place before the COVID-19 pandemic reaches a hospital system. We understand that not all EP practices are the same, and groups will face different challenges, including managing the financial burden and sequelae of decreased volume, as well as the possible “second surge” of both inpatients and outpatients who have remained at home with EP disorders until peak COVID-19 surging has dissipated. Nevertheless, we hope our experience is useful for EP sections in other parts of the country and world who, unfortunately, anticipate an influx of COVID-19 cases. As we learn from each other how to face an unprecedented modern pandemic, continued communication, collaboration, and preparedness are critical to helping our patients and each other.

Footnotes

S.K. reports institutional research grants from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Abbott, consulting fees from Abbott, Admedus, and Meril Lifesciences, and equity options from Biotrace Medical and Thubrikar Aortic Valve Inc. A.K. reports Institutional funding to Columbia University and/or Cardiovascular Research Foundation from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular, Abiomed, CSI, Philips, ReCor Medical. Personal: CME program honoraria and travel/meal reimbursements only. A.B reports serving as a medical advisory board member for Boston Scientific and Biosense Webster.

References

- 1.Altevogt BM, Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Guidance for Establishing Standards of Care for Use in Disaster Situations. Guidance for Establishing Crisis Standards of Care for Use in Disaster Situations: a Letter Report. 2009Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stefanini GG, Azzolini E, Condorelli G. Critical organizational issues for cardiologists in the COVID-19 outbreak: a frontline experience from Milan, Italy. Circulation. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakkireddy DR, Chung MK, Gopinathannair R, et al. Guidance for cardiac electrophysiology during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic from the Heart Rhythm Society COVID-19 Task Force; electrophysiology section of the American College of Cardiology; and the Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association. Heart Rhythm. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozcan C, Rottman JN, Heist EK, et al. Unpredictable battery depletion of St Jude Atlas II and Atlas+ II HF implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:717–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Notification of Enforcement Discretion for Telehealth Remote Communications During the COVID-19 Nationwide Public Health Emergency. 2020. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html. Accessed 2020, April 9.

- 6.Cobos Gil MA. Standard and precordial leads obtained with an apple watch. Ann Intern Med. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ng K, Poon BH, Kiat Puar TH, et al. COVID-19 and the risk to health care workers: a case report. Ann Intern Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buerhaus PI, Auerbach DI, Staiger DO. Older clinicians and the surge in novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]