Abstract

BACKGROUND AND IMPORTANCE

A pituitary adenoma patient who underwent surgery in our department was diagnosed with COVID-19 and 14 medical staff were confirmed infected later. This case has been cited several times but without accuracy or entirety, we feel obligated to report it and share our thoughts on the epidemic among medical staff and performing endonasal endoscopic surgery during COVID-19 pandemic.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The patient developed a fever 3 d post endonasal endoscopic surgery during which cerebrospinal leak occurred, and was confirmed with SARS-CoV-2 infection later. Several medical staff outside the operating room were diagnosed with COVID-19, while the ones who participated in the surgery were not.

CONCLUSION

The deceptive nature of COVID-19 results from its most frequent onset symptom, fever, a cliché in neurosurgery, which makes it hard for surgeons to differentiate. The COVID-19 epidemic among medical staff in our department was deemed as postoperative rather than intraoperative transmission, and attributed to not applying sufficient personal airway protection. Proper personal protective equipment and social distancing between medical staff contributed to limiting epidemic since the initial outbreak. Emergency endonasal endoscopic surgeries are feasible since COVID-19 is still supposed to be containable when the surgeries are performed in negative pressure operating rooms with personal protective equipment and the patients are kept under quarantine postoperatively. However, we do not encourage elective surgeries during this pandemic, which might put patients in conditions vulnerable to COVID-19.

Keywords: Adenoma, COVID-19, Case report, Endonasal, Endoscopic

ABBREVIATIONS

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- FT3

free triiodothyronine

- TSH

thyroid-stimulating hormone

- WBC

white blood cell count

BACKGROUND AND IMPORTANCE

Since late December 2019, the COVID-19 outbreak has been causing concerns in the medical community and WHO characterized it as a pandemic on March 11th, 2020.1 Wuhan used to be the epic center of the outbreak, a pituitary adenoma patient was the first diagnosed COVID-19 case in our department and 14 medical staff were confirmed infected later, and this specific case has been cited several times but without accuracy or entirety,2,3 misinformation could lead to unnecessary psychological burden upon medical service providers. With this ongoing pandemic, we feel obligated to report it and share our thoughts and precautions to limit the epidemic among our medical staff.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patient Information

A 70-yr-old male patient with a 2-mo history of visual impairment was admitted and then diagnosed with pituitary adenoma in late December 2019. His past medical history was significant for hypertension, diabetes, and heart attack, and medications included perindopril, metformin hydrochloride, atorvastatin, acarbose, and amlodipine. He had a family history of hypertension and denied direct or indirect contact with COVID-2019 patients or visiting Huanan Seafood Market in last 2 wk. Physical exam revealed bitemporal hemianopsia.

Diagnostic Assessment

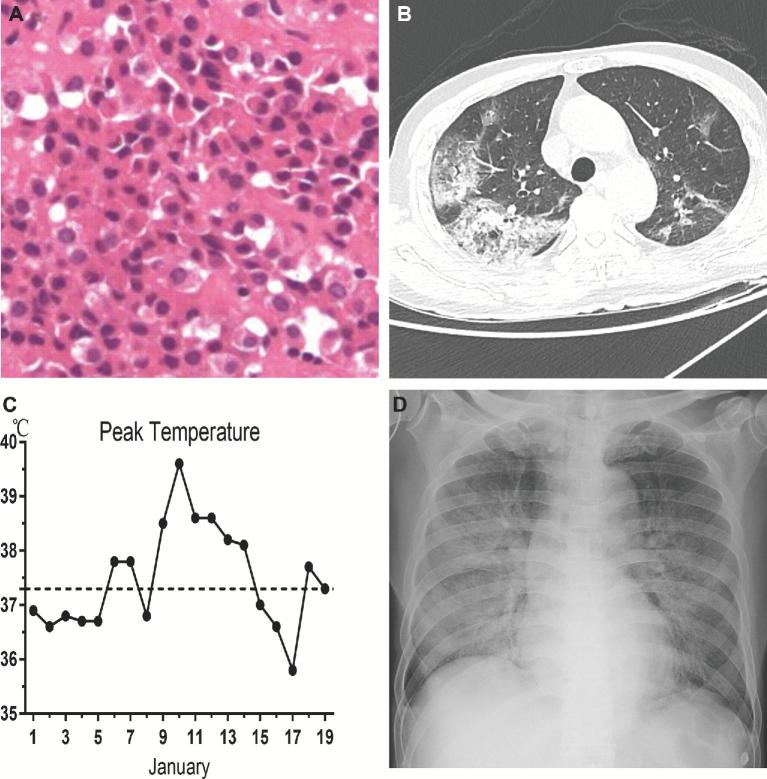

Routine Chest X-ray (Figure 1), blood test and hormonal screening (Table 1) showed no indication for infection, except for anemia and minor hormonal imbalances. Given the patient's metallic prosthetic teeth, head computed tomography (CT) was scheduled instead of magnetic resonance imaging and indicated a well-defined mass lesion in the sellar region, measuring 3.8, 3.5, and 4.5 cm in size and compressing the optic chiasm (Figure 1B-1D). Pathology confirmed pituitary adenoma (Figure 2A).

FIGURE 1.

Preoperative imaging studies. A, Preoperative X-ray indicated no obvious abnormalities. ©2020 Xiaobing Jiang. Used with permission. B, Axial preoperative head CT indicated well-defined mass lesion in sellar region, measuring 3.8, 3.5, 4.5 cm in size and compressing the optic chiasm, black arrows indicates the boundary. C, Coronal reconstruction of head CT scan, black arrows indicates the boundary. D, Sagittal reconstruction of head CT scan, black arrows indicates the boundary. Note that the patient had metallic prosthetic teeth which made it impossible to obtain magnetic resonance imaging.

TABLE 1.

Main laboratory Test Results Pre- and Postoperation

| Categories | Preoperation | January 7 | January 9 | January 10 | January 11 | January 12 | References | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC | 5.92 | 7.07 | 16.93 | 9.98 | 3.5-9.5 | x109/L | ||

| RBC | 4 | 3.86 | 4.23 | 4.1 | 4.3-5.8 | x1012/L | ||

| Hemoglobin | 120 | 115 | 121 | 117 | 130-175 | g/L | ||

| Hematocrit | 35 | 33.7 | 37.4 | 36.6 | 40-50 | % | ||

| MCV | 87.5 | 87.3 | 88.4 | 89.2 | 82-100 | fl | ||

| MCH | 30.1 | 29.7 | 28.6 | 28.5 | 27-34 | pg | ||

| MCHC | 344 | 340 | 324 | 319 | 316-354 | g/L | ||

| Platelet count | 172 | 165 | 205 | 147 | 125-350 | x1012/L | ||

| Neutrophil percentage | 69.63 | 87.51 | 89.5 | 92.6 | 40-75 | % | ||

| Lymphocyte percentage | 21.5 | 6.2 | 7.7 | 5.6 | 20-50 | % | ||

| Monocyte Percentage | 4.91 | 6.26 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 3-10 | % | ||

| Eosinophil percentage | 3.33 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0.4-8.0 | % | ||

| Basophil Percentage | 0.6 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0-1 | % | ||

| Neutrophil count | 4.12 | 6.19 | 15.16 | 9.24 | 1.8-6.3 | x109/L | ||

| Lymphocyte count | 1.27 | 0.44 | 1.31 | 0.56 | 1.1-3.2 | x109/L | ||

| Monocyte count | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.17 | 0.1-0.6 | x109/L | ||

| Eosinophil count | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.02-0.52 | x109/L | ||

| Basophil | 0.04 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.01 | <0.06 | x109/L | ||

| Cortisol 8am | 115 | 247 | 37-194 | μg/L | ||||

| Cortisol 4pm | 62 | 31 | 29-173 | ug/L | ||||

| Testosterone | 0.52 | 0.4 | 1.42-9.23 | ng/mL | ||||

| Prolactin | 8.6 | 1 | 2.6-18.1 | ng/mL | ||||

| Estradiol | <10 | 15 | 11-44 | pg/mL | ||||

| FSH | 59.14 | 7.21 | 1.0-12 | IU/L | ||||

| LH | 2.03 | 0.72 | 0.57-12.07 | IU/L | ||||

| FT4 | 10.5 | 12 | 14.4 | 9-19.18 | pmol/L | |||

| FT3 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 1.8 | 2.63-5.7 | pmol/L | |||

| TSH | 0.6267 | 0.2655 | 0.0801 | 0.35-4.94 | μIU/mL | |||

| PCT | 1.68 | <0.5 | μg/L | |||||

| CRP | 323 | <8 | mg/L |

WBC, white blood cell count. RBC, red blood cell count. MCV, mean corpuscular volume. MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin. MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration. FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone. LH, luteinizing hormone. FT4, free thyroxine. FT3, free triiodothyronine. TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone. PCT, procalcitonin. CRP, C-reactive protein.

FIGURE 2.

Postoperative pathology, imaging and peak axillary temperature records. A, Pathological frozen section of the resected tumor(20x), indicating pituitary adenoma. Immunohistology staining (Figures not shown): Syn (+), ACTH (−), GH (−), Ki 67 (LI < 1%). B, Lung CT scan, 5 d post operation, on January 11th, showed multiple ground glass opacities, effusion and consolidation. C, the peak axillary temperature starting January 1st through 19th, the horizontal dotted line intercepted y-axis at 37.3°C, the cutoff for fever. D, Chest X-ray at bedside, 7 d post operation, on January 13th, after the patients’ symptoms deteriorated, showed multiple bilateral opacities, mainly located in right lung. D, ©2020 Xiaobing Jiang. Used with permission.

Therapeutic Intervention

The patient showed no contraindications in preoperative evaluation 1 d prior surgery. Endonasal endoscopic pituitary adenoma resection was performed in a regular operating room on January 6th. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage occurred during the resection process, and the surgeon managed to fix the dural tears promptly. He had a transient fever of 37.8°C within 20 h postoperation, which could be resolved by physical method of cooling, and he showed no cough or neurological symptoms in that period. Oral prednisone and levothyroxine were administered 2- and 4-d postoperation, respectively, when hormonal test revealed low prolactin, testosterone, free triiodothyronine (FT3), and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH; Table 1).

Three days later, he had a fever of 38.5°C, intravenous meropenem administration was initiated on January 10th accordingly for potential intracranial infection indicated by significant white blood cell count (WBC) elevation (Table 1) and CSF leakage during surgery. The doctors arranged a lumbar puncture soon but failed to collect sufficient CSF. The patient didn’t show Kernig's or Brudzinski's sign but experienced fatigue and dry cough, therefore alternative examinations were scheduled to identify common pathogens, including influenza A and B, adenovirus, Chlamydophila, and Mycoplasma pneumonia, etc.

On January 11th, common pathogen tests (Table 2) came out negative but lung CT (Figure 2B) and blood test (Table 1) turned positive, the former indicated ground glass sign, pleura effusion, and consolidation; the latter showed decreasing lymphocyte count with slightly increasing WBC. After consulting with Department of Infectious Disease, oral antiviral therapy started. The patient was treated as ‘pneumonia of unknown etiology’ in a quarantine room. Special protocol was initiated and all personnel were requested to wear protective equipment when visiting him since then.

TABLE 2.

Common Pathogen Screening list

| Categories | Results | Sample |

|---|---|---|

| Influenza A virus RNA | Negative | Oral Swab |

| influenza B virus RNA | Negative | Oral Swab |

| Respiratory syncytial virus RNA | Negative | Oral Swab |

| Respiratory syncytial virus IgM | Negative | Serum |

| Adenovirus IgM | Negative | Serum |

| Chlamydophila pneumoniae IgM | Negative | Serum |

| Chlamydophila pneumoniae IgG | Negative | Serum |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgM | Negative | Serum |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgG | Negative | Serum |

| Coxsackie B virus | Negative | Serum |

| Bacterial Screening | Negative | Sputum |

RNA, ribonucleic acid.

The fever persisted for 6 d, from January 9th through 14th, with an average peak of 38.6°C (38.1°C∼39.6°C) (Figure 2C) regardless of antibiotic and antiviral therapies. Laboratory test revealed dramatic increase of procalcitonin and C-reactive protein (Table 1) on January 12th. On January 13th, he began to experience severe cough, fatigue, sputum production, shortness of breath, and low peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2 70%-78%). The X-ray demonstrated multiple bilateral opacities (Figure 2D), he was put on non-invasive ventilation to maintain oxygen saturation. On January 18th, the oral swab was taken, and test result revealed positive for SARS-CoV-2 the next day. The main event during his hospitalization was illustrated chronologically (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Time-line of main event of the patient. Numbers in the middle square blocks represent the date of month. Grey color square blocks denote the day with fever and white color block denote the day without. The fever is defined that the axillary temperature greater than 37.3°C. CT, Computed Tomography; WBC, white blood cell count; FT3, free triiodothyronine; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Follow-up and Outcomes

The patient was later transferred to a designated hospital and died of respiratory failure 4 wk after surgery.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was approved by the Institutional Review Board; the patient and his close relatives gave informed consent.

DISCUSSION

The patient had a postoperative fever followed by increasing WBC and CSF leakage during surgery; it would be logical from a neurosurgeon's perspective to speculate intracranial infection. Noticing the cough, doctors scheduled alternative tests which complied with ‘fever of unknown etiology,4 also known as COVID-19 now. Its frequent onset symptom, fever, made COVID-19 deceptive.

Following the first COVID-19 case in our department, 4 nurses who contacted with him directly before quarantine without protective equipment were infected, and 10 more staff who did not contact him were also confirmed later. The 14 staff fully recovered and returned back to work as of March 31st. It's worth noting that none of them participated in the surgery. Furthermore, with proper personal protective equipment and precautions since January 11th, none of those who contacted with him directly were infected, including his attending group who paid daily visit to the patient. In our retrospective view, patient quarantine, proper personal protective equipment, and social distancing between medical staff contributed to limiting epidemic among medical staff since the initial outbreak.

The median incubation period of COVID-19 was estimated to be 5.1 d, 97.5th percentile was 11.5 d,5 based on epidemiological characteristics it's reasonable to speculate that he developed a latent infection of SARS-CoV-2 prior operation and stress inflicted by neurosurgical procedure and anesthesia6 and potential postoperative hypopituitarism7 might impact his immune system. Transmission from an asymptomatic patient was reported,8 and higher viral loads were detected soon after symptom onset, with higher viral loads detected in the nose than in the throat.9 The estimated half-life of SARS-CoV-2 in aerosols was approximately 1.1 to 1.2 h,10 but it does not necessarily mean the aerosols cannot be filtered by surgical masks or N95 respirators. Endonasal endoscopic surgery is performed in a narrow, longitudinal canal, assisted by suction and irrigation. The chance that aerosols and droplets originating in nostrils escape the suction and are inhaled subsequently by surgeons is rare. Therefore, we think it is not wise to cancel all the endonasal endoscopic surgeries especially the emergency ones, such as pituitary apoplexy, and COVID-19 is supposed to be containable when the surgeries are performed in negative pressure operating rooms with sufficient personal protective equipment and the patients are kept under quarantine postoperatively. While we do not encourage elective surgeries during this pandemic, which might impact patients’ immune system and put them in conditions vulnerable to COVID-19.

CONCLUSION

The deceptive nature of COVID-19 results from its most frequent onset symptom, fever, a cliché in neurosurgery, which makes it hard for surgeons to differentiate from postoperative intracranial infection. The COIVD-19 epidemic among medical staff in our department was deemed as postoperative rather than intraoperative transmission, and attributed to not applying sufficient personal airway protection. Proper personal protective equipment and social distancing between medical staff contributed to limiting epidemic since the initial outbreak. Emergency endonasal endoscopic surgeries are feasible since COVID-19 is still supposed to be containable when the surgeries are performed in negative pressure operating rooms with sufficient personal protective equipment and the patients are kept under quarantine postoperatively. However, we do not encourage elective surgeries during this pandemic, which might put patients in conditions vulnerable to COVID-19.

Disclosures

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 81272778 and 81974390 to Dr X. Jiang) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant 2020kfyXGYJ010 to Dr X. Jiang). The authors have no personal, financial, or institutional interest in any of the drugs, materials, or devices described in this article.

Acknowledgments

Junxian Hu, Min Feng, Shun’an Hu, and Kai Chen were a part of the medical team for this patient and contributed their hard work to the treatment.

REFERENCES

- 1. WHO Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. 2020; https://www.who.int/westernpacific/emergencies/covid-19. Accessed April 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schwartz J, King CC, Yen MY. Protecting healthcare workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak: lessons from Taiwan's severe acute respiratory syndrome response. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cohen E. Disease detectives hunting down more information about “super spreader” of Wuhan coronavirus. https://www.cnn.com/2020/01/23/health/wuhan-virus-super-spreader/index.html. Accessed April 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li J-Y, You Z, Wang Q et al.. The epidemic of 2019-novel-coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia and insights for emerging infectious diseases in the future. Microbes Infect. 2020;22(2):80-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q et al.. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. published online: March 10, 2020. (doi:10.7326/M20-0504). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stollings LM, Jia LJ, Tang P, Dou H, Lu B, Xu Y. Immune modulation by volatile anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 2016;125(2):399-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mukherjee A, Helbert M, Davis J, Shalet S. Immune function in hypopituitarism: time to reconsider? Clin endocrinol. 2010;73(4):425-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P et al.. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Eng J Med. 2020;382(10):970-971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M et al.. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Eng J Med. 2020;382(12):1177-1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH et al.. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Eng J Med. published online:2020. (doi:10.1056/ NEJMc2004973). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]