Abstract

This clinical demonstration project used facilitation to implement VA Video to Home (VTH) to deliver evidence-based psychotherapies to underserved rural Veterans, to increase access to mental health care. Participants were Veterans seeking mental health treatment at “Sonny” Montgomery Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Jackson, MS, and/or its six community-based outpatient clinics. Measures included patient encounter and demographic data, patient and provider interviews, reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance (RE-AIM) factors, measures of fidelity to manualized evidence-based psychotherapies (EBPs), and qualitative interviews. The project was deemed feasible; 93 (67 men, 26 women, including 77 rural, 16 urban) patients received weekly EBPs via VTH. Nearly half were Black (n = 46), 36 of whom (78.3%) were also rural. Fifty-three (48.4%) were Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom Veterans. Ages varied widely, from 20 to 79 years. Primary diagnoses included posttraumatic stress disorder (41), depressive disorders (22), anxiety disorders (nine), insomnia (eight), chronic pain (eight), and substance use disorder (five). Fifteen clinicians were trained to deliver eight EBPs via VTH. Growth in number of Veterans treated by telehealth was 10.12 times and mental health visits were 7.34 times greater than the national annual average of growth for telehealth at VHA facilities. Illustrative examples and qualitative data from both patients and providers suggested overall satisfaction with VTH. This demonstrates the benefits of VTH for increasing access to mental health treatment for rural patients and advantages of an implementation facilitation strategy using an external facilitator. Continuing research should clarify whether certain patients are more likely to participate than others and whether certain EBPs are more easily delivered with VTH than others.

Keywords: Evidence-based practice; Mental health; Mobile health; Telehealth; Veterans; Rural health services; Technology; Areas, medically underserved; Posttraumatic stress disorder; Psychology

Introduction

Incorporating technological innovations to improve or facilitate title delivery of mental health care has rapidly evolved (Hilty et al. 2017), for example, integration of technology-assisted therapies that can be completed autonomously (Carroll et al. 2008) or with the support of a therapist to increase treatment fidelity (Craske et al. 2009). Advances in telehealth technology, including tools and services, have made remote delivery of care more accessible, with an estimated 60% of all health care institutions in the USA offering some form of telehealth (Office of Health Policy 2016; Tuekson et al. 2017), for example, delivery of evidence-based psycho therapies (EBPs) to patients at home or other secure locations of then-choosing, is one of the most promising innovations in telehealth (Aciemo et al. 2016, 2017; Gilmore et al. 2016; Gros et al. 2011a, b, 2013, 2016; Strachan et al. 2012). While clinic-to-clinic delivery of telehealth has been used for some time and shown to be an effective alternative to in-person care (Hilty et al. 2013), the option for a patient to receive care directly to his or her home has the potential to address additional barriers patients face when accessing care (e.g., lack of transportation, distance/travel time, taking time off from work/school, arranging child care, stigma associated with clinic visits).

Despite growing technological advances, access to innovations and providers who are trained in remote delivery of EBPs is still lacking. Barriers to care can be especially limiting for rural patients, who often have less access to EBPs than their urban counterparts (Mott et al. 2014a). Rural clinics are particularly susceptible to shortages in EBP-trained therapists, stemming from factors such as limited access to adequate provider training (Cully et al. 2010), and challenges such as isolation of rural providers (Cueciare et al. 2016), thus preventing many patients from accessing needed mental health care.

One strategy helping to circumvent staff shortages in rural areas has been establishing a structure of regional hubs of providers delivering EBPs to distant patients, often referred to as a top-down approach. This project used an evidence-based implementation facilitation strategy (Harvey and Kitson 2015; Ritchie et al. 2017) in a bottom-up approach to train providers at the G.V. “Sonny” Montgomery Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Jackson, MS, and its associated community-based outpatient clinics, to deliver EBPs via VA Video to Home (VTH). The goal of the current project was to increase access to evidence-based psychotherapy for under-served rural patients by encouraging providers to include VTH deliveiy methods as part of regular clinical practice.

Method

This clinical demonstration project occurred between October 2014 and September 2016.

The external facilitator chose Jackson due to the density of highly rural Veterans who access this healthcare system and prior participation in a study involving video telehealth delivery of therapy for PTSD from the main clinic to surrounding community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs; Lindsay et al. 2015). In addition, a PTSD psychologist was already delivering EBPs, serving many rural Veterans, with an established referral network from the six CBOCs. Another selection criteria for identifying this site specifically was the EBP Clinic, which housed several providers and psychologists who served in leadership roles related to the delivery of outpatient EBPs (e.g., evidence-based practice coordinator).

Collaborators

Guided by the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework (i.e., context, evidence, and facilitation), the implementation facilitation strategy benefited from innovative characteristics described by previous researchers (Kirchner et al. 2014). It was highly partnered and involved the Michael E. DeBakey VAMC in Houston, TX, and G.V. “Sonny” Montgomery VAMC in Jackson, MS; Veterans Integrated Service Network 16; South Central Mental Illness Research and Education and Clinical Center; Mental Health Quality Enhancement Research Initiative; VA Central Office; and National Center for Telehealth and Technology. Similarly, stakeholders (site leadership, healthcare providers, and Veterans) at all levels collaborated in developing the implementation facilitation strategy. It included both an external facilitator and two internal facilitators, all of whom were psychologists.

Implementation Facilitation

Facilitators worked with key stakeholders to identify and address potential problems and evaluate progress through audit and feedback. The external facilitator liaised between site leadership and providers, leading weekly teleconference calls providing a forum for a community of practice, helped connect providers with national EBP trainers, explained ways EBP delivery might differ using VTH, and liaised between national and local stakeholders, was responsible for staying abreast of technological advances (e.g., equipment, which transitioned from desktop computers to iPads, and, eventually, 4G tablets to overcome barriers to access); maintained compliance with changing regulations, often requiring adjustments in the training/certification protocol; provided educational outreach; dealt with emerging issues (e.g., how to handle licensing queries across state lines); and assisted with using equipment (e.g., how to order technology, instruction on set-up and use, and guidance related to incorporating necessary data into medical records).

Internal facilitators served as clinical champions by supporting and promoting adoption of the program among colleagues, delivering presentations to leadership, and assisting with troubleshooting (e.g., scheduling issues related to VTH; identifying appropriate attendees for meetings; providing information about organizational structure, culture, procedures), clinically supervising other clinicians administering EBPs, including administration of instruments at appropriate times during therapy to measure fidelity to the EBPs. Internal facilitators met with the external facilitator weekly for the first year, and bimonthly in the second year.

Facilitation activities evolved and underwent adaptation to meet the needs of each site. Critical to success were monthly formative evaluations to identify barriers and facilitators to implementation, involving audit and feedback of data, such as identification of patients being reached in terms of patient demographics, rurality, and diagnoses being treated, as well as relative successes of strategies used to deal with barriers to expand access, such as frequency of referrals between sites and identification of factors contributing to their success.

Clinical Intervention

Providers completed telehealth training, consisting of a web-based curriculum covering the modality and safety procedures (i.e., information on suicide prevention and emergency care) and an in-person training to ensure skills and competencies for clinicians. Eligible rural Veterans receiving treatment at the Jackson VAMC and the surrounding community clinics were referred to an initial in-clinic meeting with a mental health provider, where they received appropriate equipment (e.g., webcam or tablet) and instructions for receiving treatment at home. The clinical intervention included weekly delivery of manualized EBPs for mental health care. EBPs were chosen by clinicians providing treatment based on clinical judgment, including cognitive processing therapy (CPT); prolonged exposure (PE) therapy; interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT); acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT); and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

Evaluation

A mixed-method program evaluation was conducted, involving data extraction and in-depth qualitative interviews. Quantitative data included patient encounter and demographic data from the VHA Data Portal national telehealth database and were collected and analyzed during the first and third quarters of each fiscal year and then applied for quality improvement as necessary. After treatment completion, individual qualitative interviews were conducted via telephone with consenting Veterans (n = 5) and providers (n = 5). Veteran interviews lasted 25–51 min; provider interviews lasted 27–50 min. All interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using directed content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon 2005) with Atlas.ti (v. 7) software (Scientific Software Development Gmbh, Berlin, Germany).

Evaluation of VTH implementation was loosely based upon the RE-AIM framework (Virginia Tech College of Agriculture and Life Sciences n.d.) and evaluated reach (number of patients receiving treatment), effectiveness (retention in therapy when delivered via VTH), adoption (number of providers using VTH), implementation (fidelity to the delivery method and consistency with national telehealth standards), and maintenance (degree of sustainability of VTH after external facilitator decreases involvement).

Annual rates of VTH per 1000 encounters were calculated and graphically plotted (number of VTH encounters in mental health in study year/number of all VTH encounters in study year X 1000 visits for mental health per VHA fiscal year X 1000), and annual rates of VTH per unique Veterans treated in mental health for both the study site in Jackson, and VHA nationwide at VAMCs delivering VTH for three study years were similarly calculated: 2014 (baseline), 2015 (study year 2), and 2016 (study year 3), respectively. The average change (percentage) in rates between baseline and 2016 for both encounter-based rates and unique Veteran-based rates of VTH delivery was also calculated. There was no formal testing for statistical significance of changes given that there was a single test site.

The project was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the “Sonny” Montgomery VAMC, the Michael E. DeBakey VAMC, and Baylor College of Medicine.

Results

During this 2-year project, 93 (77 rural, 16 urban) Veterans received EBPs via VTH; 67 were men, and 26 were women. Women were overrepresented (27.9%), as only 6% of Veterans who seek services at the VHA are women (Friedman et al. 2011). Nearly 50% were Black (n = 46, of whom 36, or 78.3%, were rural; one declined to answer; one multiethnic; two unknown; and 43 Whites). Fifty-three (48.39%) were Veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom. A wide range of ages were served: 20 to 29 years (11), 30 to 39 years (24), 40 to 49 years (27), 50 to 59 years (21), 60 to 69 years (7), and 70 to 79 years (3). Primary diagnoses included PTSD (41), depressive disorders (22), anxiety disorders (9), insomnia (8), chronic pain (8), and substance use disorder (5). Fifteen clinicians were trained to deliver EBPs via VTH, including four psychologists, one social worker, one licensed marriage and family therapist, two licensed professional counselors, and seven psychology interns. Patients receiving an adequate dose (at least eight sessions (Karlin and Cross 2014)) of an EBP that was delivered by fulltime staff (not including intern clinicians) included CBT for chronic pain, 75% (6 of 8 recipients); CBT for insomnia, 75% (6 of 8 recipients); CPT, 68% (15 of 22 recipients); PE, 66% (2 of 3 recipients); ACT, 50% (1 of 2 recipients); and CBT for depression, 67% (6 of 9 recipients).

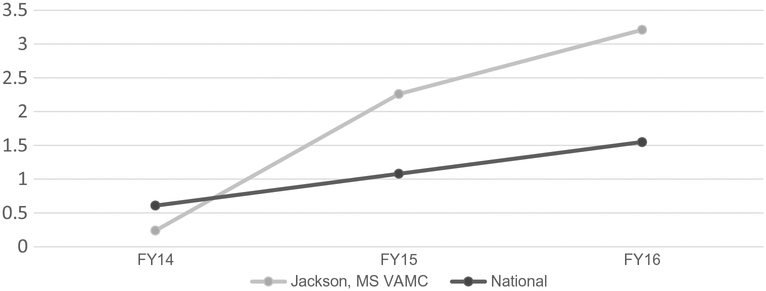

There were 141 VAMCs during the study period, including the study intervention site in Jackson. By controlling for size of VAMCs nationally, based on enrollment, prevalence rates were calculated (per 1000 Veterans receiving mental health services). Annual VTH delivery rates per 1000 unique Veterans in 2014 were low, both in the VHA nationwide and in Jackson, as VTH was first introduced to VHA in 2013 (Fig. 1). Rates increased in each subsequent study year in both the VHA nationwide and at Jackson; however, the relative increase in prevalence rates was much higher in Jackson, with final absolute prevalence rates of VTH per 1000 Veterans also higher in Jackson.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence rates of unique Veterans (per 1000) in VA Video to Home

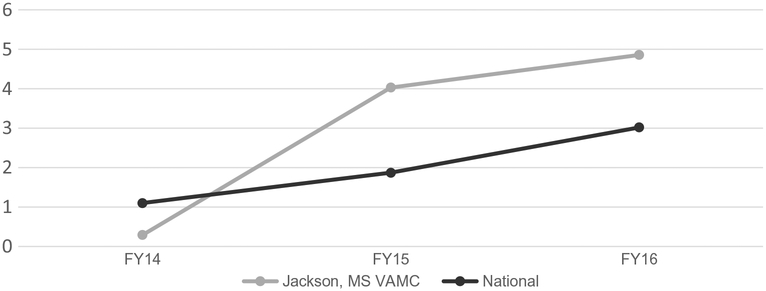

As expected, a similar trend was observed in number of overall mental health encounters (Fig. 2), with Jackson demonstrating a greater increase in prevalence rate than the national average across the VHA. Growth in number of Veterans receiving mental health treatment via VTH was 10.12 times higher than the national average across the VHA (see Fig. 1). The number of visits of mental health encounters via VTH at Jackson VAMC and its clinics grew at a rate 7.34 times the national average (see Fig. 2). Overall, there were 522 encounters for 93 patients. Travel miles saved (from Veterans’ homes to the site where they were/would have been receiving treatment) totaled 106,332.80 miles. Travel pay (calculated on the same basis as travel miles), saved totaled $44,128.36. Thirty-seven different counties were served, most of which were highly rural. Importantly, growth was sustained at the end of the 2-year implementation effort.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence rate of visits (per 1000) via VA Video to Home

Qualitative data from both patients and providers suggest overall satisfaction with VTH, and we provide highlights and illustrative examples below. Additional qualitative feedback can be found in Tables 1 and 2. Providers describe how VTH increased access to care (i.e., reach) for rural patients: “Well, I think that what we’re finding is that we’re tapping into Veterans that aren’t being seen…it’s [VTH] making you know Veterans who are coming to CBOCs or coming to [the VAMC], it’s making it more convenient for them” (provider 1). Several factors have the potential to impact the effectiveness of delivering EBPs via VTH; for example, VTH can increase patient engagement in treatment but also could reinforce a patient’s maladaptive behaviors if not carefully considered. One provider describes such a scenario:

Table 1.

Summary of qualitative feedback from provider interview

| RE-AIM domain | Provider qualitative feedback |

|---|---|

| VTH expands the reach of mental health care for rural Veterans | “It’s a lot to ask somebody to commit to an hour a week for 12 weeks [for mental health treatment]. But if they live 2 h away or more, now you are asking them to commit to taking off an entire day of work a week, and that is just tremendous … so I think access to care is really one of the biggest advantages [of VTH].” Provider 3 |

Factors influencing the effectiveness of VTH as a mode of treatment delivery, e.g.:

|

“So I remember seeing a Veteran with PTSD … her maintenance man was supposed to come because she was uncomfortable. But that was interesting because … you get to see her like triple lock the door … you are seeing that home environment. In some situations, that can be good.” Provider 2 |

| “The only time that…we have all just sort of a little bit hesitated would be more on dealing with people with severe anxiety and really wanting to not allow them to continue to avoid leaving the house.… We do the first couple sessions in their home and then teach them to come out and see us in person.…” Provider 3 | |

Positive (+)/negative (−) factors influencing provider VTH adoption, e.g.:

|

“I mean I had to spend 20 min walking this guy and his wife through logging in and then it did not work … it doesn’t really bother me that much because I would just be flexible and just adapt my session based on that. Other providers like that is like a death no. They are not interested in doing it [i.e. VTH] if stuff like that happens.” Provider 1 |

| “At the beginning, like maybe some people feel like it’s [i.e. VTH] going to be this huge obstacle and it’s not gonna really be the same … it does not really affect that rapport of that service as much as I would have thought.” Provider 7 | |

| VTH implementation benefits from advanced planning (e.g., advanced mailing of treatment worksheets), and providers’ abilities to adapt treatment to the home environment (e.g., sharing of homework exercises) as well as address technological issues during sessions | “A couple of times the technology was a problem, and we had to finish a session on the telephone. … Fortunately, that was people that I already had a pretty good decent relationship with. So it was fine. We just rolled with it. It was just a nuisance.” Provider 6 |

| “You have to be a little bit more flexible. You have to think a little and you know think ahead a bit more. You know cannot just whip out a handout and show it to them.” Provider 1 |

|

| Maintenance of VTH is contingent on identifying local clinical champions to promote adoption, and improvements to internet/technology, scheduling procedures, and real-time sharing of information during treatment sessions | “If my providers go and use this new system and you have not figured the glitches out, I am gonna get pushback, and once they push against it, it’ll be really hard to get them back. … But you have to have like an advocate that is a provider that can kind of address those concerns because if there are any frustrations. … it’s going to reinforce the idea that this [i.e. VTH] does not work.” Provider 2 |

Table 2.

Patient feedback from the qualitative interviews

| RE-AIM domain | Patient qualitative feedback |

|---|---|

Mental health care via VTH reaches Veterans who experience several barriers to care, e.g.:

|

“I also have social anxiety and panic attacks so that the shuttle with 14 strangers for 2½ hours and … we all have different appointments so I have to stay … all day until all of the other Veterans’ appointments to be done and then we have to ride the shuttle back. And so that just creates a whole lot of other problems for me…” Patient 1 |

| “I think everybody needs therapy but if I had to travel for that, that’s not my main problem and so I probably would not do it.” Patient 6 | |

| “She [i.e. the provider] would actually be available to talk to me about 6:00 because that gave me enough time to get up at 5:00 and get myself together and then I’ll be talking to her and then once we got through, it was 7:00 so I would leave and go to work. So she made it to work just so she could talk to me early.” Patient 7 | |

Veteran feedback identifies factors that positively (+)/negatively (−) influence the effectiveness of VTH as a mode of mental health care delivery, e.g.:

|

“Being in the home made it [i.e. VTH] comfortable because I hate hospitals in the first place. My feeling behind going to the doctor’s office, it makes me nervous, and being in the comfort of my own home added that extra comfort.” Patient 4 |

| “I just had a feeling … that yeah well this is easy to talk about you know over the internet and some things maybe felt a little less comfortable speaking about and you wish that ‘Oh, I wish I was there in person. I would feel more comfortable.’” Patient 6 | |

| “There were several times you know during the course of the services that like I said we had some hiccups in the system to where not only me getting frustrated but the therapist was really getting frustrated. … You know but we would you know we worked through it.” Patient 8 | |

| Veteran feedback on VTH is positive overall with ease of set-up/use and comfort with technology promoting adoption; use of tablets and improving how providers share information in sessions are potential factors to increase Veteran uptake of VTH | “I am comfortable with the computer but it was something she was telling me to do that I did not know how to do and I had to get my niece to show me and then she called me back and my niece had showed me what to do so I could get on there.” Patient 7 |

| “I have got 5 of the guys that were up under me [in the military], I have got them involved in it. … So I kept telling them that they need to go see if they can get signed up for it, and a couple of them did …” Patient 4 | |

| “It’s [i.e. VTH] one of the best things since sliced bread.” Patient 8 |

[T]here was a concern as to whether if this is a person who has an anxiety about driving and we’re doing that [i.e., treatment] from home, is that reinforcing that? … How I’ve kind of handled that for myself is that if that can get them started in treatment … make the goal at home that they start driving. Then, you know at least we’re giving them something. Because if that anxiety is so high that they’re not gonna drive. Say they start missing appointments, we’re not going to get through the treatment that they need anyway (provider 2).

Additionally, VTH removes the logistical challenge of finding available clinic space for treatment and offers providers flexible hours for appointments, which helps promote uptake (i.e., adoption) of the technology. However, technical issues and concerns over licensing and delivering care across state lines were aspects that can negatively impact provider adoption. Feedback also suggests how providers need to remain flexible when using VTH, as the EBP may need to be adapted to “fit” the technology platform. For example, one provider discusses how he/she had to adapt treatment for delivery over VTH:

[A] lot of the … work that we do involves a lot of handouts and a lot of materials, and figuring out what is the best way to kind of share that with the patient was something that was really helpful. So for instance, when you’re sitting with someone in the room, it’s really easy to just kind of sit close to them at that point with that handout and walk them through it… [s]o being able to adapt to that was something that took a little bit of time. … [O]ne of the things that was really useful was being able to share the screen. … It gave me a tool to really like not miss out on that opportunity of like explaining or drawing different concepts or using different analogies and examples that required us to kind of be like looking at the same thing (provider 7).

Patients felt that VTH addressed several barriers to care, such as distance to the VAMC and availability of transportation, parking, work schedules, and health conditions that made travel to the VHA difficult One Veteran noted how the 60-mile drive to the VAMC would cause swelling and pain in his/her knee, which he/she found “aggravating” (patient 4). Veteran feedback also indicates how the technology platform did not affect patient/provider rapport, they were comfortable receiving care in the home environment, and minor technological “hiccups” (patient 8) were not an issue. However, our feedback suggests that patients felt some topics or issues may be better suited to discuss in-person than over VTH, and that certain skills like meditation do not translate well to the VTH platform: “Yeah, that was not very comfortable online I must say. … sometimes I like to meditate but doing it online and you have your camera on and they have their camera on and you’re both meditating and it’s kind of it feels uncomfortable” (patient 6). The Veterans we interviewed reacted positively to VTH, with one remarking that VTH is “… one of the best things since sliced bread” (patient 8). Veteran feedback hints that ease of set-up/use of VTH and comfort with the technology are potential factors in overall satisfaction. To improve Veteran satisfaction, using tablet devices and improving how providers and patients share information over the technology platform were mentioned.

Discussion

This 2-year clinical demonstration project increased access to weekly treatment of EBPs, delivered to the home, for 93 patients; half were racial minorities or women, and most were rural. Fifteen clinicians at six CBOCs completed training in eight EBPs and learned to deliver them via VTH. The number of Veterans treated was more than seven times the national VHA average for growth of patients treated via telehealth, and further, this progress was sustained through project completion. The project was deemed feasible and sustainable.

The project allowed 93 patients to receive EBPs at home, eliminating travel to a clinic for treatment, the most significant barrier to receipt of mental health treatment for Veterans (Buzza et al. 2011). Although one study reported Veterans with PTSD were less likely than those without to be willing to use electronic communication for therapy delivery (Whealin et al. 2015), 41 patients with PTSD received from eight to 12 weekly sessions of EBP at home. It also agrees with the results of a previous study comparing preliminary results of outcomes of VTH and in-person delivery for PTSD, which successfully delivered PE therapy for Veterans with PTSD via VTH (Yuen et al. 2015). In addition, more than half of all patients with PTSD in this study received a “full dose” (at least eight of 12 weekly sessions (Karlin and Cross 2014)) of either PE, CPT, or acceptance and commitment therapy via VTH. This compares favorably with the findings of a large clinical trial (Sehnurr et al. 2007), and three clinic-based studies (Gros et al. 2011b; Jeffreys et al. 2014; Mott et al. 2014b) of PE therapy in which less than half of Veterans with PTSD completed treatment, and also with four clinic-based studies of CPT, which had dropout rates of from 31 % to 50% (Chard et al. 2010; Davis et al. 2013; Jeffreys et al. 2014; Mott et al. 2014b;). Findings from this clinical demonstration project support the notion that remote delivery to the home may impact retention in treatment.

VTH may be particularly helpful for delivering mental health services to populations who are traditionally underserved in the VHA system. As Gilmore et al. (2016) suggested, VTH effectively reaches women victims of military sexual trauma, which often results in PTSD, because it prevents them from having to appear in an environment that reminds them of the one in which they experienced trauma. Additionally, a high percentage of patients receiving treatment were Black, and many of these individuals were also rural. VTH enabled delivery of treatment to this group, believed to be less likely to receive formal mental health treatment than other racial groups in rural parts of the southern USA (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2003).

Strengths of this project included an implementation facilitation strategy involving external and internal facilitators, resulting in greater expansion of VTH than most VHA facilities experienced during the years of this project. Including clinical champions allowed expansion of services beyond the main medical center to surrounding clinics, especially during the maintenance period, thus sustaining delivery of services by training new employees in a timely manner. Internal facilitators had been heavily involved in training before participating in this project. Another strength was being able to provide appropriate technology for interested patients, as minority groups generally face greater barriers to accessing hardware and private internet space (Wykes and Brown 2016).

Although feasible, this project had a number of limitations. The project focused on remote delivery of EBPs to the home and did not include delivery of pharmacotherapy. This clinical demonstration project highlights the use of implementation facilitation to increase uptake of VTH as a mode of mental health treatment delivery, and, therefore, the focus was placed on evaluating the implementation effort rather than the effectiveness of the mental health interventions. One way to expand the scope of services would be to include clinicians able to prescribe medications (psychiatrists, primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, and pharmacists). Qualitative data were summative rather than formative in nature, which limited our ability to identify additional barriers and facilitators in real-time. Also, the technology evolved throughout the project, which meant responses may not have fully reflected the technology used. Some clinicians had more experience working with the technology than others when they provided qualitative responses, and experience level may have influenced their responses.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates benefits of VTH for increasing access to mental health treatment for rural patients and advantages of an implementation facilitation strategy using an external facilitator and internal facilitators and a bottom-up approach to deliver EBPs via VTH. Continuing research should clarify whether certain patients are more likely to participate than others and whether certain EBPs are more easily delivered with VTH than others.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mona Ritchie, PhD, MSW, and Jo Ann Kirchnei; MD, for implementation facilitation training and mentoring; and Rhonda Johnson, PhD, BC-FNP, BC-ANP, and Mr. John Peters for assistance and expertise in providing telehealth services.

Funding This work is the result of a grant from the VA Office of Rural Health, N16-FY15Q1-S1-P01392 (4440), to Jan Lindsay, support by the VA South Central Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, and use of resources and facilities at the Houston VA HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN13–413). The opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the U.S. Government or Baylor College of Medicine.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Aciemo R, Gros DF, Ruggiero IJ, Hemandez-Tejada MA, Knapp RG, Lejuez CW, et al. (2016). Behavioral activation and therapeutic exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder: a noninferiority trial of treatment delivered in person versus home-based telehealth. Depression and Anxiety, 33(5), 415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aciemo R, Knapp R, Tuerk P, Gilmore AK, Lejuez C, Ruggiero K, et al. (2017). A non-inferiority trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder: in person versus home-based telehealth. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 89, 57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzza C, Ono SS, Turvey C, Wittrock S, Noble M, Reddy G, et al. (2011). Distance is relative: unpacking a principal barrier in rural healthcare. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(Supp 12), 648–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Martino S, Nich C, Babuscio TA, Nuro KF, et al. (2008). Computer-assisted delivery of cognitive-behavioral therapy for addiction: a randomized trial of CBT4CBT. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(1), 881–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chard KM, Schumm JA, Owens GP, & Cottingham SM (2010). A comparison of OEF and OIF Veterans and Vietnam Veterans receiving cognitive processing therapy. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(1), 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Rose RD, Lang AJ, Welch SS, Campbell-Sills L, Sullivan G, et al. (2009). Computer assisted delivery of cognitive behavior therapy for anxiety disorders in primary care settings. Depression and Anxiety, 26,235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucciare MA, Curran GM, Craske MG, Abraham T, McCarthur MB, Marchant-Miros K, et al. (2016). Assessing fidelity of cognitive behavioral therapy in rural VA clinics: design of a randomized implementation effectiveness (hybrid type III) trial. Implementation Science, 11(1), 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cully JA, Jameson JP, Phillips LL, Kunik ME, & Fortney JA (2010). Use of psychotherapy by rural and urban Veterans. Journal of Rural Health, 26(3), 225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JJ, Walter KH, Chard KM, Parkinson RB, & Houston WS (2013). Treatment adherence in cognitive processing therapy for combat-related PTSD with history of mild TBI. Rehabilitation Psychology, 55(1), 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SA, Phibbs CS, Schmitt SK, Hayes PM, Herrera L, & Frayne SM (2011). New women Veterans in the VHA: a longitudinal profile. Womens Health Issues, 21(4 suppl), S103–S111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AK, Davis MT, Grubaugh A, Resnick H, Birks A, Denier C, et al. (2016). “Do you expect me to receive PTSD care in a setting where most of the other patients remind me of the perpetrator?”: home-based telemedicine to address barriers to care unique to military sexual trauma and Veterans affairs hospitals. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 48, 59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros DF, Veronee K, Strachan M, Ruggiero KJ, & Aciemo R (2011a). Managing suicidality in home-based telehealth. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 17(6), 332–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros DF, Yoder M, Tuerk PW, Lozano BE, & Aciemo R (2011b). Exposure therapy for PTSD delivered to Veterans via telehealth: predictors of treatment completion and outcome and comparison to treatment delivered in person. Behavior Therapy, 42(2), 276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros DF, Morland LA, Greene CJ, Aciemo R, Strachan M, Egede LE, et al. (2013). Delivery of evidence-based psychotherapy via video telehealth. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 35(4), 506–521. [Google Scholar]

- Gros DF, Lancaster CL, López CM, & Aciemo R (2016). Treatment satisfaction of home-based telehealth versus in-person delivery of prolonged exposure for combat-related PTSD in Veterans. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. [Epub ahead of print, September 26,2016], 10.1177/1357633X16671096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey G, & Kitson A (2015). Implementing evidence-based practice in healthcare: a facilitation guide. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Hilty DM, Ferrer DC, Parish MB, Johnston B, Callahan EJ, & Yellowlees PM (2013). The effectiveness of telemental health: a 2013 review. Telemedicine and e-Health, 19(6), 444–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilty DM, Chan S, Hwang T, Wong A, & Bauer AM (2017). Advances in mobile mental health: opportunities and implementation for the spectrum of e-mental health services. mHealth, 3(34), 3–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffreys MD, Reinfeld C, Nair PV, Garcia HA, Mata-Galan E, & Rentz TO (2014). Evaluating treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder with cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure therapy in a VHA specialty clinic. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(1), 108–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin BE, & Cross G (2014). From the laboratory to the therapy room. National dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychotherapies in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs health care system. American Psychologist, 69(11), 19–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner JE, Ritchie MJ, Pitcock JA, Parker LE, Curran GM, & Fortney JC (2014). Outcomes of a partnered facilitation strategy to implement primary care mental health. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29(Suppl 4), S904–S912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay JA, Kauth MR, Hudson S, Martin LA, Ramsey DJ, Daily L, et al. (2015). Implementation of video telehealth to improve access to evidence-based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Telemedicine and e-Health, 21, 6 10.1089/tmj.2014.0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott JM, Grubbs KM, Sansgiry S, Fortney JC, & Cully JA (2014a). Psychotherapy utilization among rural and urban Veterans from 2007–2010. The Journal of Rural Health, 31, 235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott JM, Mondragon S, Hundt NE, Beason-Smith M, Grady RH, & Teng EJ (2014b). Characteristics of US Veterans who begin and complete prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy for PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(3), 265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Health Policy, Office ofthe Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluations. (2016). Report to Congress: e-health and telemedicine. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie MJ, Dollar KM, Miller CJ, Oliver KA, Smith JL, Lindsay JA, et al. (2017). Using implementation facilitation to improve care in the Veterans Health Administration (version 2). Veterans Health Administration, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) for Team-Based Behavioral Health; Available at: https://www.queri.research.va.gov/tools/implementation/Facilitation-Manual.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Engel CC, Foa EB, Shea MT, Chow BK, et al. (2007). Cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in women. Journal of the American Medical Association, 297(8), 820–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strachan M, Gros DF, Ruggiero KJ, Lejuez CW, & Aciemo R (2012). An integrated approach to delivering exposure-based treatment for symptoms of PTSD and depression in OEF/OEF Veterans: preliminary findings. Behavior Therapy, 43(3), 560–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuckson RV, Edmunds M, & Hodgkins ML (2017). Special report: telehealth. New England Journal ofMedicine, 377(16), 1585–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2003). Achieving the promise: transforming mental health care in America. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Virginia Tech College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, (n.d.). Reach effectiveness adoption implementation (RE-AEM). RE-AIM.org. http://re-aim.org/. Accessed 6 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Whealin JM, Seibert-Hatalsky A, Howell JW, & Tsai J (2015). E-mental health preferences of Veterans with and without probable posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 52(6), 725–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykes T, & Brown M (2016). Over promised, over-sold and underperforming?—e-health in mental health (editorial). Journal of Mental Health, 25(1), 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen EK, Gros DF, Price M, Zeigler S, Tuerk PW, Foa EB, et al. (2015). Randomized controlled trial of home-based telehealth versus in-person prolonged exposure for combat-related PTSD in veterans: preliminary results. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(6), 500–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]