Abstract

Despite growing appreciation of the need for research on autism in adulthood, few survey instruments have been validated for use with autistic adults. We conducted an institutional ethnography of two related partnerships that used participatory approaches to conduct research in collaboration with autistic people and people with intellectual disability. In this article, we focus on lessons learned from adapting survey instruments for use in six separate studies. Community partners identified several common problems that made original instruments inaccessible. Examples included: (1) the use of difficult vocabulary, confusing terms, or figures of speech; (2) complex sentence structure, confusing grammar, or incomplete phrases; (3) imprecise response options; (4) variation in item response based on different contexts; (5) anxiety related to not being able to answer with full accuracy; (6) lack of items to fully capture the autism-specific aspects of a construct; and (7) ableist language or concepts. Common adaptations included: (1) adding prefaces to increase precision or explain context; (2) modifying items to simplify sentence structure; (3) substituting difficult vocabulary words, confusing terms, or figures of speech with more straightforward terms; (4) adding hotlinks that define problematic terms or offer examples or clarifications; (5) adding graphics to increase clarity of response options; and (6) adding new items related to autism-specific aspects of the construct. We caution against using instruments developed for other populations unless instruments are carefully tested with autistic adults, and we describe one possible approach to ensure that instruments are accessible to a wide range of autistic participants.

Lay summary

Why is this topic important?

To understand what can improve the lives of autistic adults, researchers need to collect survey data directly from autistic adults. However, most survey instruments were made for the general population and may or may not work well for autistic adults.

What is the purpose of this article?

To use lessons learned from our experience adapting surveys—in partnership with autistic adults—to create a set of recommendations for how researchers may adapt instruments to be accessible to autistic adults.

What did the authors do?

Between 2006 and 2019, the Academic Autism Spectrum Partnership in Research and Education (AASPIRE) and the Partnering with People with Developmental Disabilities to Address Violence Consortium used a participatory research approach to adapt many survey instruments for use in six separate studies. We reviewed records from these partnerships and identified important lessons.

What is this recommended adaptation process like?

The adaptation process includes the following:

(1) Co-creating collaboration guidelines and providing community partners with necessary background about terminology and processes used in survey research;

(2) Collaboratively selecting which constructs to measure;

(3) Discussing each construct so that we can have a shared understanding of what it means;

(4) Identifying existing instruments for each construct;

(5) Selecting among available instruments (or deciding that none are acceptable and that we need to create a new measure);

(6) Assessing the necessary adaptations for each instrument;

(7) Collaboratively modifying prefaces, items, or response options, as needed;

(8) Adding “hotlink” definitions where necessary to clarify or provide examples of terms and constructs;

(9) Creating new measures, when needed, in partnership with autistic adults;

-

(10)

Considering the appropriateness of creating proxy report versions of each adapted measure; and

-

(11)

Assessing the adapted instruments' psychometric properties.

What were common concerns about existing instruments?

Partners often said that, if taking a survey that used the original instruments, they would experience confusion, frustration, anxiety, or anger. They repeatedly stated that, faced with such measures, they would offer unreliable answers, leave items blank, or just stop participating in the study. Common concerns included the use of difficult vocabulary, confusing terms, complex sentence structure, convoluted phrasings, figures of speech, or imprecise language. Partners struggled with response options that used vague terms. They also felt anxious if their answer might not be completely accurate or if their responses could vary in different situations. Often the surveys did not completely capture the intended idea. Sometimes, instruments used offensive language or ideas. And in some cases, there just were not any instruments to measure what they thought was important.

What were common adaptations?

Common adaptations included: (1) adding prefaces to increase precision or explain context; (2) modifying items to simplify sentence structure; (3) substituting difficult vocabulary words, confusing terms, or figures of speech with more straightforward terms; (4) adding hotlinks that define problematic terms or offer examples or clarifications; (5) adding graphics to increase clarity of response options; and (6) adding new items related to autism-specific aspects of the construct.

How will this article help autistic adults now or in the future?

We hope that this article encourages researchers to collaborate with autistic adults to create better survey instruments. That way, when researchers evaluate interventions and services, they can have the right tools to see if they are effective.

Keywords: survey adaptation, accessibility, community-based participatory research, autism in adulthood, intellectual and developmental disability, psychometrics, patient-reported outcome measures

Introduction

Despite autism being a lifelong disability, the vast majority of autism research, advocacy, and services have focused on children.1 Not surprisingly, reviews on almost any topic in the adult autism literature—be it physical or mental health, health care, employment, social services, social functioning, or other life outcomes—highlight the paucity of data on adulthood and the presence of important methodological concerns about including autistic adults in research.2–9 Accordingly, in the United States, the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee has called for increased research on adult services in its strategic plan.1 However, accurately evaluating the effectiveness of services interventions depends on the existence of validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Whereas some research may rely on administrative or observational data, studies evaluating services interventions—especially interventions that aim to be patient-centered—usually need to combine such data with PROMs. PROMs may exist for many of the outcomes of interest to the autistic community, but most have not been validated in this population and are likely inaccessible to autistic adults. As a result, studies often inappropriately rely on parental or caregiver report, which can equally decrease the validity of findings and raises ethical concerns.10 Similarly, the use of measures validated only with general populations may yield inaccurate findings in populations of autistic adults or may exclude participants with greater disability-related challenges.

Recommendations exist for translating instruments to other languages,11 culturally adapting instruments,12 or adapting materials for use with people with intellectual disability.13 However, the literature provides little guidance on how to adapt instruments to be accessible to autistic adults, what the adaptation process should entail, or what main issues need to be considered when adapting measures for this population. Thirteen years ago, when we started collecting survey data from autistic participants, we created adaptation processes based on the first author's experience conducting participatory research with other populations. In the intervening years, we have used a participatory approach to create or adapt multiple instruments for use with populations of autistic adults or people with intellectual disability and have included such instruments in six separate studies. This article reviews our experience, focusing on lessons learned that may help other researchers adapt or create measures to be used with autistic adults and people with intellectual disability. While we used a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach on our projects,14 we offer recommendations for a variety of collaborative relationships, including partnerships that use a CBPR approach, teams that use a co-production model, and researchers who work with autistic adults in an advisory capacity.

Institutional Ethnography

Institutional context

This article describes work conducted by two closely related academic–community partnerships. The Academic Autism Spectrum Partnership in Research and Education (AASPIRE; www.aaspire.org)15,16 is an ongoing National Institutes of Health-funded partnership based in the United States. Founded in 2006, AASPIRE conducts research on topics of high importance to the autistic community, including health care,17–21 employment, well-being,22 and autistic burnout. The Partnering with People with Developmental Disabilities to Address Violence Consortium was formed to conduct a single Centers for Disease Control-funded survey about violence and health in people with developmental disabilities in Oregon and Montana (the “Partnering Project”).23–26

Both partnerships use a CBPR approach14 wherein academic and community partners collaborate throughout all phases of the research and share equally in the decision-making process.16 Both teams include academic researchers, autistic adults, family members, and disability and health services providers (with some partners serving in multiple roles). The Partnering Project was focused more broadly on adults with developmental disabilities, so it also included nonautistic adults with intellectual disability and other developmental disabilities. In both partnerships, some team members have had additional physical, sensory, or mental health disabilities.

AASPIRE has been regularly holding team meetings with academic and community partners via text-based group chats since 2006 and has a very active team e-mail list for asynchronous communication. Given the long length of the collaboration, some partners have left the team and others have joined. The Partnering Project held in-person meetings regularly between 2009 and 2013 while the project was actively funded; since then, a subset of the initial team members have communicated remotely, as needed, via a team e-mail list. More information on the CBPR aspects of both partnerships is available elsewhere.15,16,25,27–30

Ethnographic methods

We recently conducted an institutional ethnography of these partnerships to create the AASPIRE Guidelines for the Inclusion of Autistic Adults in Research16 and the AASPIRE Web Accessibility Guidelines for Autistic Web Users.27 These ethnographies used an iterative process, which combined discussions among current team members with a review of several hundred artifacts (e.g., meeting minutes, study protocols, grant proposals, comments from peer-reviewers, and published articles). For the current article, we focus on our experiences adapting or creating survey instruments to offer additional context and depth to the recommendations and to provide detailed examples for other researchers who wish to conduct surveys with autistic adults.

To accomplish this goal, we conducted the following additional artifact reviews:

We compared the original and final versions of all survey instruments that the group formally adapted and tested in at least one sample of autistic adults.

We re-reviewed all meeting minutes where community partners discussed survey instruments.

We reviewed available change logs describing changes the team made to surveys.

Where available, we reviewed early drafts of surveys that included community partners' suggested edits and comments.

As AASPIRE communications primarily occur via text-based chat or e-mail, we reviewed all available AASPIRE meeting transcripts related to instrument development or adaptation. We also identified and reviewed several additional e-mail threads discussing survey instruments.

We invited current and recently active team members from both partnerships to participate in this extension of our work and co-author this article. The first two authors are AASPIRE's founding academic and community co-directors (C.N. and D.M.R.). Both served in leadership positions in each of the related AASPIRE and Partnering Project studies, participated in all the original discussions under review, and conducted the original artifact reviews to create the AASPIRE guidelines.16,27 Although the second author (D.M.R.) has since transitioned to an academic role,28 she served as a community partner through most of the survey adaptation process. The third author (K.E.M.) has served as an AASPIRE academic partner since the beginning of the partnership and was the evaluator for the Partnering Project. The remaining co-authors served as community partners or research staff on one or more of the studies included in the review. The first three authors and a research assistant (K.Y.Z.) conducted the additional artifact reviews necessary for this analysis; the remainder deepened the review with their recollections and helped form final recommendations.

Survey studies included in the ethnography

For this article, we focused on five AASPIRE survey-based studies and the Partnering Project survey (see Table 1 for more details.). AASPIRE has also occasionally provided consults to other researchers who seek feedback from our community partners on their own research projects. In this ethnography, we reviewed a consultation with a researcher who wanted to adapt measures to study anxiety and insomnia in autistic adults.

Table 1.

Survey Studies Included in This Review

| Construct | Original instrument/source | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| AASPIRE Healthcare Experiences Survey | ||

| An online survey of 209 autistic adults and 228 nonautistic adults with and without other disabilities, comparing their experiences with health care17 and barriers to care.21 | ||

| Unmet health care needs | Items from the 2002/2003 Joint Canada/United States Survey of Health39 | Created the 6-item Unmet Healthcare Needs Checklist (re-used in future health care studies) |

| Health care utilization | Items from the 2002/2003 Joint Canada/United States Survey of Health39 and the 2007 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Questionnaire—Adult Access to Health Care & Utilization40,41 | Adapted items used again in future health care studies |

| Satisfaction with patient–provider communication | Items from the NIH Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS)42 | Created first version of the AASPIRE Patient–Provider Communication Scale (asking about past 12 months). Revised version used in other health care studies |

| Health-related Internet use | Items from the NIH Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS)42 | |

| Bias in health care | Scale used in the Commonwealth Fund's 2001 Health Care Quality Survey43 | Created two versions of each item: one about race/ethnicity and another about disability |

| Barriers to health care | Barriers to Accessing Health Care for People with Disabilities Checklist | Created and tested the Barriers to Healthcare Checklist–Long Form; recommended consolidation to the Barriers to Healthcare Checklist–Short Form, which was then used in future studies |

| Chronic disease self-efficacy | Chronic Disease Self-Efficacy Scales—from Stanford Patient Education Research Center44,45 | Separated items into two scales, one for that can be answered by anyone and the other with items than can only be answered by participants with chronic diseases |

| Supports in accessing health care | Created de novo | |

| Demographic and disability characteristics | Created de novo | |

| AASPIRE Identity, Community, and Well-Being Survey | ||

| An online survey of 151 autistic and 173 nonautistic adults focused on online community involvement, identity, and well-being.22,46 | ||

| Autistic identity | Disability Identity Scale—Chicago Center for Disability Research47 | Adapted to reflect autistic identity rather than disability identity |

| Involvement in the online community | Gallop Poll and new items | Adapted to reflect constructs of interest to study, including online autistic community involvement |

| Sense of community | Sense of Community Index 2 (SCI-2)48 | Selected subscales most relevant to study and referenced online autistic community |

| Psychological well-being | Scales of Psychological Well-being49 | Selected subscales most accessible to autistic adults and of theoretical interest to study |

| Social support over the Internet/face-to-face | Social Provisions Scale | Changed item lead to measure social support online and in-person |

| Autism Healthcare Accommodations Tool Test–Retest | ||

| A 2-week test–retest study with 59 autistic adults (42 of whom participated directly and 17 via a proxy reporter) to assess the reliability of the AHAT—a survey-based tool to identify and report patient's accommodation needs.20 | ||

| Health care accommodation needs | Created de novo | Developed the Autism Healthcare Accommodations Survey, used in future interventions |

| AASPIRE Healthcare Toolkit Evaluation Study | ||

| A pre- and postintervention survey to test the AASPIRE Healthcare Toolkit with a national convenience sample of 170 autistic adults (136 of whom participated directly and 34 via a proxy reporter).20 | ||

| Unmet health care needs | Unmet Healthcare Needs Checklist (Originally adapted in AASPIRE Healthcare Experiences Survey) | |

| Health care utilization | Originally adapted in AASPIRE Healthcare Experiences Survey | |

| Satisfaction with patient–provider communication | AASPIRE Patient–Provider Communication Scale (originally adapted in AASPIRE Healthcare Experiences Survey) | Changed from past 12 months to last visit |

| Barriers to health care | Barriers to Healthcare Checklist–Short Form | First test of short-form |

| Health care self-efficacy | Healthcare Self-Efficacy Scale–new instrument | |

| AASPIRE Healthcare Toolkit Integration Study | ||

| A pre- and postintervention survey with 244 autistic adults (194 of whom participated directly and 50 via a proxy reporter) to evaluate the integration of the AASSPIRE Healthcare Toolkit in three health care systems in California and Oregon.33 | ||

| Unmet health care needs | Unmet Healthcare Needs Checklist (Originally adapted in AASPIRE Healthcare Experiences Survey) | |

| Health care utilization | Originally adapted in AASPIRE Healthcare Experiences Survey | |

| Satisfaction with patient–provider communication | AASPIRE Patient–Provider Communication Scale (originally adapted in AASPIRE Healthcare Experiences Survey; revised in AASPIRE Healthcare Toolkit Evaluation Study) | |

| Barriers to health care | Barriers to Healthcare Checklist–Short Form | |

| Health care self-efficacy | Healthcare Self-Efficacy Scale (created in AASPIRE Healthcare Toolkit Evaluation Study) | Factor analysis revealed two factors: individual health care self-efficacy and relationship-dependent health care self-efficacy |

| Provider/staff use of accommodations | Created de novo | |

| Visit preparedness | Created de novo | |

| Partnering with People with Developmental Disabilities to Address Violence Project | ||

| An in-person survey, using an accessible Audio-Computer Assisted Survey Interview, with 350 adults with developmental disabilities in Oregon and Montana to assess the relationship between violence and health in people with developmental disabilities.23–25 | ||

| Physical symptoms | Patient Health Questionnaire—Physical Symptom Scale (PHQ-15)50 | |

| Secondary conditions | Health Conditions Checklist,51 which itself was an adaptation of the Secondary Conditions Surveillance Instrument52 | |

| Depression | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10)53,54 | |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | PTSD Checklist55,56 | |

| Perceived stress | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4)57,58 | |

| Social support | MOS-Social Support Scale59,60 | |

| Substance use | Items loosely based off of CAGE Questionnaire61 and AUDIT-C62 | |

| Child abuse | Items from Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionaire63 | Factor analysis of adapted items yielded three factors: Childhood Physical Abuse, Childhood Sexual Abuse, and Childhood Disability Abuse |

| Adult abuse | Abuse items used in Safer and Stronger Program64 | |

| Perpetrator characteristics | Perpetrator characteristic items used in Safer and Stronger Program64 | |

| Barriers to help seeking | Barriers to help-seeking items used in Safer and Stronger Program64 | |

| Help-seeking behaviors | Created de novo | |

| Life impact of abuse | Created de novo | |

| Disability characteristics and number of functional limitations | Created de novo | |

| Experience taking questionnaire | Created de novo | |

AASPIRE, Academic Autism Spectrum Partnership in Research and Education; AHAT, Autism Healthcare Accommodations Tool; AUDIT-C, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Concise; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Lessons Learned

Processes for survey adaptation or creation

While we have refined our adaptation processes over time, our partnerships have used a relatively consistent approach that includes:

-

(1)

Co-creating collaboration guidelines and providing community partners with necessary background about terminology and processes used in survey research;

-

(2)

Collaboratively selecting which constructs to measure;

-

(3)

Discussing each construct so that we can have a shared understanding of what it means;

-

(4)

Identifying existing instruments for each construct;

-

(5)

Selecting among available instruments (or deciding that none are acceptable and that we need to create a measure de novo);

-

(6)

Assessing the necessary adaptations for each instrument;

-

(7)

Collaboratively modifying prefaces, items, or response options, as needed;

-

(8)

Adding “hotlink” definitions where necessary to clarify or provide examples of terms and constructs;

-

(9)

Creating new measures, when needed, in partnership with autistic adults;

-

(10)

Considering the appropriateness of creating proxy report versions of each adapted measure; and

-

(11)

Assessing the adapted instruments' psychometric properties (Table 2).

Table 2.

Instrument Adaptation Process

| Activity | CBPR or co-production model | Advisory model |

|---|---|---|

| Create collaboration guidelines and provide com. partners with necessary background about terminology and processes used in survey research | Acad. and com. partners | Acad. researcher and com. advisors (but consider working with pre-existing teams) |

| Select which constructs to include in the survey | Acad. and com. partners | Acad. researchers |

| Discuss constructs to ensure a shared understanding of what each one means | Acad. and com. partners | If possible, discuss with com. advisors |

| Identify existing instruments to measure each construct. Prepare materials to share with com. partners. | Acad. partners | Acad. researchers |

| • General approach to instrument adaptation, including desire to only make changes that are absolutely necessary. | ||

| • Copies of each instrument and its instructions/scoring. | ||

| • Lay-friendly summary of how well each measure has been studied in other populations; if and how it has been used with autistic adults; and available psychometric data. | ||

| Review existing instruments to determine which ones to use | Community partners | Community advisors |

| • Comment on how well each instrument captures intended construct. | ||

| • Comment on how easy it would be to complete each instrument as is. | ||

| • Comment on whether or not each instrument uses offensive or ableist concepts. | ||

| • Comment on any other concerns related to using instrument with autistic adults. | ||

| • Comment on which adaptations, in general, would be needed to make the instrument accessible to autistic adults and how easy it would be to make those adaptations. | ||

| Decide which instruments to use or adapt. If no instrument can be adapted feasibly, then consider creating a new measure. | Acad. and com. partners | Acad. researchers |

| For each existing instrument that is being adapted, review preface, individual items, and response options, paying particular attention to | Primarily com. partners (although academic partners actively participate in the discussion) | Community advisors |

| • Difficult vocabulary or confusing terms | ||

| • Convoluted sentence structure | ||

| • Sentence length and complexity | ||

| • Incomplete sentences | ||

| • Double negatives | ||

| • Imprecise language | ||

| • Figurative speech | ||

| • Confusing or inconsistent pronouns | ||

| • Use of the passive voice | ||

| • Need for additional context | ||

| • Need to answer differently when thinking of different situations | ||

| • Overlap between what is being assessed and underlying autism | ||

| • Ableist or offensive language | ||

| • Imprecise or incomplete response options | ||

| Brainstorm possible solutions to each issue. Consider the following potential adaptations | Acad. and com. partners work together to make each adaptation, using a consensus process, to make final decisions on each measure | Community advisors offer suggestions; academic researchers make final decisions based on com. advisor feedback |

| • Addition or modification of preface or instructions to increase precision or explain context | ||

| • Simplifying sentence structure | ||

| • Changing passive voice to active voice | ||

| • Clarifying pronouns or changing them to be consistent | ||

| • Substituting difficult vocabulary words, confusing terms, or figures of speech with more straightforward terms | ||

| • Adding hotlinks that define problematic terms or offer examples or clarifications | ||

| • Adding graphics to increase clarity of response options | ||

| • Adding new items related to autism-specific aspects of the construct. | ||

| Try to avoid | ||

| • Changing intended meaning of an item | ||

| • Decreasing precision when substituting difficult vocabulary with simpler terms | ||

| • Increasing sentence length or complexity to a great degree when trying to add precision | ||

| • Removing items from scored scales | ||

| • Changing overall scoring of scored scales, unless absolutely necessary. | ||

| If creating new measures, design, create, review, and finalize items with each of the above considerations in mind. | Acad. and com. partners discuss which items should be included; academic partners create draft measure; com. partners review measure; group jointly adapts and finalizes scale | Acad. researchers create draft measure; com. advisors review measure and offer suggested edits; academic researchers make final decisions |

| If creating proxy report version | Acad. and com. partners | Acad. researchers |

| • Discuss which constructs are and are not possible for a proxy to report on | ||

| • Pay close attention to wording of items to make it clear when proxy is answering about the participant vs. about themselves. | ||

| Assess psychometric properties of new or adapted instruments. Consider using | Acad. and com. partners collaborate on validations studies (with separate population of autistic adults or people with intellectual disability) | Acad. researchers conduct study with separate population of autistic adults or people with intellectual disability |

| • Cognitive interviewing to assess content validity | ||

| • Pilot testing full survey to assess participant burden and feasibility | ||

| • Cronbach's alpha to assess internal consistency reliability for scored scales | ||

| • Test–retest comparison to test stability over time | ||

| • Factor analysis to assess structural validity | ||

| • A priori hypothesis testing of expected associations to assess construct validity |

Acad., academic; CBPR, community-based participatory research; com., community.

Community partners with different educational attainment or functional accommodation needs have sometimes noted different concerns or suggested contradicting adaptations (e.g., differing preferences for simpler versus more specific language). We entertained the idea of creating multiple versions of instruments, but in all cases so far, we have been able to reach consensus by working together to better understand the barriers and then brainstorm solutions that work across these different needs. As such, we strongly recommend that researchers collaborate with community partners with a wide range of characteristics and backgrounds to be able to better represent the wide spectrum of autistic adults or people with intellectual disability.

Our own projects have used a CBPR approach, with autistic adults (and in the case of the Partnering Project, people with other developmental disabilities) co-leading the entire process, collaborating as equal partners throughout each step, and jointly making all decisions using a consensus process. The instrument adaptation process has been at times intense and time-consuming. For example, in the Partnering Project, where we adapted or created 15 instruments for use with people with developmental disabilities, we were usually able to adapt only one instrument during each 2- to 3-hour in-person meeting (after academic researchers and the community partners on the steering committee had already identified instruments and created written materials for the other community partners). Given that most community partners can be expected to participate in at most two to three meetings per month, the instrument adaptation process took over a year to complete.

We recognize that not all researchers are willing or able to use a CBPR model. We envision that teams who use a co-production model could follow very similar steps to those that we used, but without the expectation that community partners share power equally throughout all aspects of the research. However, most autism researchers do not use participatory methods at all.31,32 Given the need for at least some input from autistic adults to ensure meaningful and valid data collection, we would recommend that all autism researchers at least consider an advisory model, where autistic adults help assess existing measures and provide recommendations for possible adaptations.

Our AASPIRE consultations with other researchers serve as one example of how researchers can obtain input from autistic adults. In the example we reviewed for this ethnography, the Principal Investigator selected the constructs she wished to include and identified potential instruments. She then shared these instruments, over e-mail, with our AASPIRE community partners and asked for their feedback on which instruments were easiest to use, which items or issues caused problems, and what potential solutions might be. She then made decisions on how to adapt her survey instruments based on that feedback. This process was facilitated by the fact that our community partners already had significant experience adapting other instruments and had a strong working relationship with AASPIRE academic partners. Researchers who wish to create their own advisory boards should plan to spend the time and effort needed to build trust and to provide advisors with enough background about survey research methods to be able to participate meaningfully in the process.

Finally, some autistic adults may not be able to participate in surveys directly using the strategies and resources available to date to support direct report. In such cases, proxy reporting may be appropriate. However, proxies may not be able to report on certain constructs, especially ones that describe internal states. It is also sometimes difficult to separate their own perspective from the proxy report. Therefore, for each construct, we have thought carefully about whether or not a proxy might be able to answer on behalf of a participant, and if so, we have reworded items to make it clear when proxies are reporting on behalf of the participant versus when they are offering their own opinion.

Clearly, one must reassess the psychometric properties of adapted instruments. Data on the psychometric properties of our adapted scales are available elsewhere.17,20–25,33 Overall, the adapted and new scales demonstrated promising psychometric characteristics, although further research needs to confirm their validity in other samples.

Common concerns about existing instruments and proposed adaptations

Our community partners have found many existing instruments that are well studied in general populations to be inaccessible to autistic adults or people with intellectual disability. In reviewing available instruments, partners often remarked that, if taking a survey that used these instruments, they would experience significant confusion, frustration, anxiety, or anger. They repeatedly stated that, faced with such measures, they would offer unreliable answers, leave items blank, or just stop participating in the study. Their comments raise significant concerns both about the validity and risks of studies that use instruments, which have not been adapted or tested with autistic adults.

We noticed the following concerns that were common across multiple instruments:

1. Language complexity and pragmatics

Community partners across all studies noted many issues related to the language used in existing instruments. Some concerns echoed well-known issues for people with intellectual disability or low literacy, including the use of difficult vocabulary, confusing terms, complex sentence structure, double negatives, or convoluted phrasings. In many cases, we were able to substitute difficult vocabulary (e.g., “confide in”) with simpler terms (e.g., “share personal information”). Notably, we often were able to simplify complicated phrasing without changing the meaning of the item. However, partners also identified language concerns that may be more specific to autism, such as the use of figures of speech or imprecise language. Again, in most cases, we were able to substitute problematic phrases with more concrete and specific language.

However, in some cases, the solutions were more challenging. For example, some partners' initial suggestions to simplify language resulted in other partners no longer being able to answer the items due to a loss of precision. Similarly, initial attempts to increase precision often resulted in long convoluted sentences. In such cases, we often relied on “hotlinks” that would allow users to click on the problematic phrase to obtain a definition or an example. (Research assistants administering surveys over the phone or in-person were instructed to offer these definitions or examples to participants verbally if they wanted them.) Examples of terms that needed hotlinks included those related to medical care (e.g., “preventive healthcare” or “Pap smear”) or medical concepts (e.g., feeling “emotionally numb”); vague terms or confusing terms such as “regularly” or “on guard”; or terms that could have multiple interpretations (e.g., “lonely” or “sexual activity”). Sometimes, community partners suggested the use of hotlinks when they felt that participants may need examples to understand an item.

Table 3 shows specific examples of how we adapted instruments to address such issues.

Table 3.

Sample Adaptations

| Sample adaptations involving simple substitutions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Issue | Original | Adapted |

| Difficult vocabulary | “confide in” | “share personal information” |

| “if you were confined to bed” | “if you had to stay in bed for many days” | |

| Complicated phrasing | “felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems” | “felt you could handle your personal problems” |

| “avoid thinking about or talking about a stressful experience from the past or avoid having feelings related to it” | “tried not to think about, talk about, or have feelings about a stressful experience from the past” | |

| “The paperwork to fill out is too much for me.” | “I have problems filling out paperwork” | |

| “to be more ineffective” | “less effective” | |

| Figures of speech | “things were going your way” | “things in your life were going well” |

| “feeling as if your future will somehow be cut short” | “feeling as if your life would end quickly” | |

| “could not get going” | “had trouble getting started on activities” | |

| “able to build home” | “able to create home environment” | |

| Sample adaptations involving the use of a hotlink definition or example | ||

|---|---|---|

| Issue | Item | Hotlink |

| Confusing terms |

In the last month, how much have you been bothered or upset by being “super alert” or watchful or on guard? |

On guard—constantly looking out for something bad. |

| Medical concepts or terminology |

In the last month, how much have you been bothered or upset by physical reactions when something reminded you of a stressful experience from the past? |

Physical reactions—heart pounding, trouble breathing, or sweating. |

| In the last month, how much have you been bothered or upset by feeling emotionally numb or being unable to have loving feelings for those close to you? |

Emotionally numb—not feeling much of anything; not being able to feel very happy or very sad. |

|

| Terms with potential for multiple interpretations |

During the past week I felt lonely. |

Lonely—the feeling of being alone when you do not want to be alone. |

| During the past 4 weeks, how much have you been bothered by pain or problems during sexual activity |

Sexual activity—vaginal sex, anal sex, oral sex, masturbation. |

|

| Need for examples | In the last month, how much have you been bothered or upset by a loss of interest in things that you used to enjoy? |

Things—like eating your favorite foods or spending time with the people you like. |

| Does your disability make it harder to take care of your daily personal needs without help from another person, assistive equipment, or other accommodations? | Assistive equipment—examples of assistive equipment include a wheelchair, communication device, service animal, or hearing aid. |

|

| Accommodations—examples of accommodations include ramps, changes in lighting, extra time, large print, accessible restrooms, and subtitles. | ||

| Adaptations to response options | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type of response | Original | Adaptation |

| Proportion of the time |

(a) None of the time; (b) a little of the time; (c) some of the time; (d) most of the time; (e) all of the time |

|

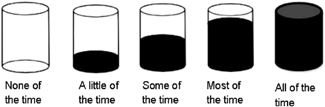

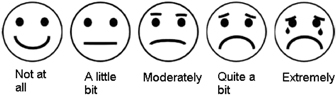

| Degree to which participant is bothered | (a) Not at all; (b) a little bit; (c) moderately; (d) quite a bit; (e) extremely |  |

| Issues addressed by inserting prefaces with greater context or instructions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Issue | Original | Adaptation |

| Need for context | In original instrument, items began with “During the past 12 months, how often did doctors or other health care providers …” | Inserted preface with the following text: “The next set of questions again asks about your ‘provider.’ Please think of your primary care provider or ‘regular doctor.’ If you do not have a primary care provider, then think of the health care provider you have seen most frequently in the past 12 months. If you have not seen a health care provider in the past 12 months, think of the last health care provider you saw.” |

| Other global issues | ||

|---|---|---|

| Issue | Solution | |

| Anxiety around not being able to answer with 100% accuracy |

• Frequent reminders to “please give your best guess from the provided answers.” |

|

| • Comment boxes on each page with the following statement: “If you are not sure how to answer a particular question, please make your best guess and move on to the next question. If you would like to, you can write comments in the comment box below. (Note: information you choose to provide in the comment box will be read, but it will not be considered an answer to the survey questions.) | ||

| Variation in potential responses in different situations |

• Changed instructions to only think about last visit with primary care provider (instead of all visits with any health care provider over the past 12 months) |

|

| Need for additional items to fully capture construct |

• Added two items about receptive and expressive communication to scale on satisfaction with patient–provider communication |

|

| • Added additional barriers about sensory sensitivities and communication skills to checklist about barriers to health care | ||

| Ableist or offensive concepts | • Selected different scales or created new measures | |

2. Likert scales with imprecise response options

Community partners, across all studies, have struggled with Likert-style response options, especially when they used vague terms that may be difficult to differentiate meaningfully (e.g., “a little of the time” versus “some of the time”). We considered removing Likert-style responses and offering yes/no responses, as is sometimes recommended for use with people with intellectual disability. However, autistic partners consistently noted that dichotomous response options were even more problematic, as it was rare for something to always be true or always be false.

Our solutions to this concern have evolved over time. For example, in an AASPIRE team meeting in 2009, community partners discussed their frustration with the “Always/Usually/Sometimes/Never” options offered on an existing health care satisfaction scale, especially as there seemed to be a significant gap between “never” and “sometimes.” They brainstormed the possibility of substituting those terms with percentages or fractions in an effort to add precision but recognized that some participants may find math problematic. Thus, they decided to leave the options as is but added the following parenthetical comment to the preface to help those participants who needed the extra information: “(‘Always' means around 100% of the time; ‘Usually’ means around 66% or 2/3 of the time; ‘Sometimes' means around 33% or 1/3 of the time; and ‘Never’ means around 0% of the time.)”

A few years later, similar issues arose in instrument adaptation meetings for the Partnering Project. This time, with a larger proportion of community partners with intellectual disability, the group discarded the notion of including percentages, even in a parenthetical comment in the preface. Ultimately, we reached consensus by adding graphics of cylinders filled to varying degrees, so that, for example, the words “most of the time” are accompanied by a cylinder that is 80% full. We created other graphics (e.g., images of faces) for other types of response options (Table 3).

3. Anxiety around answering accurately

Community partners often discussed that they would have difficulty in answering items, especially about service utilization or other fact-based questions, because they were concerned that they might not be completely accurate. For example, they might not remember the exact number of times they had been to a clinic, the date of their last preventative health services, or how often they participated in certain activities. We thus inserted frequent reminders asking participants to “make their best guess.” In early studies, we also included a comment box on every page to allow participants space to describe some of their concerns that were not easily captured in a forced-choice response scale (Table 3). Participants often commented that they really appreciated that format, but due to technical issues with our audio computer-assisted self-interview system, we did not use comment boxes in later studies. We would still recommend their use when technically feasible.

4. Potential for varying responses when thinking of different situations

Community partners often felt that they would not be able answer survey questions because their responses could vary dramatically in different situations. For example, when asked to choose between two instruments assessing sleep quality, community partners recommended against using a scale that asked questions about when they went to sleep or how many hours they slept because they thought it varied too much from night to night.

Similar issues arose when we adapted an instrument on satisfaction with patient–provider communication. The initial instrument asked participants how often doctors or other health care providers did certain behaviors over the past 12 months. Community partners felt that they could not answer because some of their providers may have demonstrated awful communication behaviors, whereas others had good communication behaviors. In our first health care survey, we decided to use a preface to guide participants to think about a single provider (their primary care provider, or if they did not have one, then the provider they saw most often). While they felt that was an improvement over the initial scale, they were still concerned about this format as they had to think about every interaction and try to average their experiences over time. Thus, the next time we used the instrument—as part of our intervention assessment—we decided to simply ask participants to think about their last visit with their primary care provider. This adaptation not only addressed the problem of having to think about multiple different encounters, but it also made it easier to assess potential changes related to the intervention. Unfortunately, though, it also made it impossible to compare results from our earlier studies.

5. Inability to fully capture construct

In several circumstances, community partners felt that existing instruments did not fully capture the construct in the context of autism. For example, while a scale assessing satisfaction with patient–provider communication addressed many important aspects of the construct (e.g., offering the patient the chance to ask questions; paying attention to emotions; involving the patient in shared decision-making), it did not specifically address receptive and expressive communication, presumably because patients in the general population may take those aspects for granted. We thus added two new items about whether the provider communicated in a way the participant could understand and whether the provider understood what the participant was trying to communicate.17,33 Similarly, a checklist assessing barriers to care in patients with disabilities included many important barriers. However, it did not include barriers that may be more common for autistic patients, such as those related to sensory sensitivities or communication. Our team thus added new items to assess such barriers.21

Reasons for creating new measures

Additional issues emerged during the instrument selection process that could not always be solved by adapting measures. Sometimes instruments were rejected outright because they used offensive conceptualizations of autism. In other cases, we were unable to identify any instruments that community partners felt captured the intended construct well enough to warrant adaptation. For example, while we identified measures of chronic illness self-efficacy, and in fact adapted one for use in our first health care survey,17 upon further reflection, partners felt that it still did not adequately address the health care self-efficacy issues most important to autistic adults. We thus created a new health care self-efficacy measure for use in our subsequent studies.20,33 Similarly, while many people recommend that health care workers make accommodations for patients with disabilities, we were unable to identify any instruments measuring whether patients received the accommodations they needed. Thus, we created a new instrument for this construct.33 While reviewing best practices for instrument creation is beyond the scope of this article, we do recommend including autistic adults in the process. The same concerns partners noted about existing measures may also affect new measures. Researchers should keep these issues in mind and work closely with autistic adults to ensure scales' content validity and accessibility.

Discussion

In our work with autistic adults and adults with intellectual disability, we have consistently found that measurement adaptation may be necessary to validly collect data directly from participants. When reviewing existing measures, our community partners often felt that original instruments were inaccessible, maintaining that they would experience significant confusion, frustration, anxiety, or anger if they took a survey with these instruments. They warned that instruments may incompletely address the intended constructs; that their use could result in unreliable or incomplete data; or that study results may apply only to the subset of the population who are able to complete the unadapted measures. We recommend researchers heed these warnings and pay close attention to the accessibility of data collection instruments.

One expects a high level of rigor when translating or adapting measures cross-culturally or cross-linguistically11,12; however, this same care and attention has not traditionally been given to studies that include autistic adults as participants. For example, two recent systematic reviews found a dearth of studies assessing the measurement properties of tools to measure depression34 or suicidality35 in autistic adults and made recommendations for needed adaptations. Yet the literature provides almost no guidance on what an adaptation process may entail.

Over the past 13 years, we have refined a process for assessing and adapting instruments to be accessible to autistic adults and people with intellectual disability. This article extends our recent guidelines for the inclusion of autistic adults in research16 by offering a deeper look at our experience adapting survey instruments and providing detailed recommendations for other survey researchers. While we believe our partnerships greatly benefited from the use of a CBPR approach, wherein community and community partners share power equally through all phases of the research, we recognize that not all researchers may choose to use this approach. The adaptation process we describe may work well for research teams that use other co-production or consultative approaches, assuming that researchers pay close attention to ethically including autistic adults or people with intellectual disability on their teams. Our recent inclusion guidelines offer additional recommendations to help teams incorporate autistic adults as co-researchers or study participants.16

In reviewing artifacts from the adaptation of multiple instruments, we found several common concerns that arose across instruments. We recommend that research teams pay particularly close attention to language complexity, precision, and concreteness; the use of Likert scales with imprecise response options; and items with varying responses when respondents are thinking of different situations. Similarly, researchers should not assume that instruments created for general populations fully capture the intended construct for autistic adults. Although our instrument adaptation process was time-consuming, we found several common adaptations (e.g., simplifying language; adding prefaces; creating hotlinks with definitions or examples; adding graphics to Likert scales; or adding items to better capture autism-specific aspects of a construct) helped address a majority of concerns. Preliminary psychometric testing of our adapted instruments is very promising, with good internal consistency reliability, test–retest reliability, content validity, structural validity, convergent validity, and responsiveness to change.17,20–25,33

While participatory research with autistic adults was rare to nonexistent when we first started AASPIRE,31,32 we are very excited by the rapid increase in the use of participatory methods with autistic adults. Several other research teams have worked with autistic adults to create, adapt, or augment survey instruments. For example, McConachie et al. examined the construct validity of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Measure (the WHOQoL-BREF) and developed nine additional autism-specific items based on consultations with groups of autistic adults in four countries.36,37 While their methods may differ from ours, like us, they found that the existing measure did not fully capture the intended construct, so they worked with autistic adults to create additional items. Similarly, Rodgers et al.65 consulted with autistic adults to adapt an anxiety scale to be more accessible to this population. Moreover, research teams have used participatory approaches to create new instruments on topics such as autistic adults' vulnerability to negative life experiences.38 While we recognize that our recommended adaptation method is certainly not the only valid approach to improving the accessibility, reliability, validity, and utility of measurement instruments, we hope our recommendations will encourage other researchers to include autistic adults in the instrument development or adaptation process, while laying out clear steps for research teams to take to make the process useful and rigorous.

Our institutional ethnography has several important limitations. First, we focused on only two closely related partnerships. While we hope that our lessons learned may help other researchers, some of our experiences may be unique to our own partnerships. Second, although we reviewed a large number of artifacts, some records have been lost over time. Similarly, given the long nature of our collaboration, many of the original community partners who had participated in the instrument adaptation processes are no longer active in our group. Our recollections may differ from theirs. Furthermore, while we have intentionally included community partners with a wide range of characteristics, our teams cannot be fully representative of the entire autism spectrum. Also, due to the time commitment required, our partnerships inherently draw community partners with interest in research and the research process. Thus, our members may be more inclined to consider those issues when suggesting adaptations than might a community member with no interest in research. Additionally, the measurement adaptation groups for different studies have some overlap in membership, so the particular concerns and preferences of certain individuals may be more strongly reflected.

Despite these limitations, we feel our findings have important implications. If researchers choose measures just because they were used in other published studies, without consideration of accessibility, they could potentially be building a body of literature based on invalid, unreliable, or unrepresentative data. We hope that researchers can use our lessons learned to partner with autistic adults to assess existing instruments and adapt them as needed. Future research needs to adapt a wider range of instruments and to test them in large heterogeneous samples of autistic adults.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all current and past AASPIRE and Partnering Project partners, as well as all the people who participated in these survey studies.

Authorship Confirmation Statement

C.N. served as the Principal Investigator (PI) or co-PI on all the studies reviewed in this ethnography, co-led the instrument adaptation processes, designed and led this analysis, and wrote the article. D.M.R. served as the community co-PI on all the AASPIRE studies, served as a Steering Committee member on the Partnering Project, co-led all instrument adaptation processes, and participated in the artifact review. K.E.M. served as the PI for the AASPIRE Wellbeing Study and an academic co-investigator on the other AASPIRE studies, led the evaluation for the Partnering Project, and helped with the artifact review for the Wellbeing Study. E.M.L. and S.L. served as research assistants on the Partnering Project and helped write portions of the article. S.K.K. participated in the instrument adaptation process as a community partner on the AASPIRE team. L.M.B. participated in the instrument adaptation process as a community partner on the Partnering Project. M.K. served as the project manager on the Partnering Project. J.M. and M.H. are current community partners on the AASPIRE team. K.Y.Z. is a student intern on the AASPIRE team and helped with the artifact review. All co-authors helped interpret data and edited and approved the article. All co-authors have reviewed and approved the article before submission. The article has been submitted solely to this Journal and is not published, in press, or submitted elsewhere.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

The AASPIRE projects discussed in this article were funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (R34MH111536 and R34MH092503); the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute (OCTRI), grant number UL1 RR024140 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research; Portland State University; and The Burton Blatt Institute and Michael Morris. The Partnering with People with Developmental Disabilities to Address Violence Project was funded by Centers for Disease Control/Association of University.

References

- 1. Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC). 2016. –2017 Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee Strategic Plan For Autism Spectrum Disorder. October 2017. Retrieved from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee website: https://iacc.hhs.gov/publications/strategic-plan/2017/ (accessed January29, 2020)

- 2. Howlin P, Arciuli J, Begeer S, et al. Research on adults with autism spectrum disorder: Roundtable report. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2015;40(4):388–393 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Howlin P, Magiati I. Autism spectrum disorder: Outcomes in adulthood. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30(2):69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Steinhausen HC, Mohr Jensen C, Lauritsen MB. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the long-term overall outcome of autism spectrum disorders in adolescence and adulthood. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;133(6):445–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cashin A, Buckley T, Trollor JN, Lennox N. A scoping review of what is known of the physical health of adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Intellect Disabil. 2018;22(1):96–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shattuck PT, Roux AM, Hudson LE, Taylor JL, Maenner MJ, Trani J-F. Services for adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(5):284–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taylor JL, McPheeters ML, Sathe NA, Dove D, Veenstra-VanderWeele J, Warren Z. A systematic review of vocational interventions for young adults with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):531–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kirby AV, Baranek GT, Fox L. Longitudinal predictors of outcomes for adults with autism spectrum disorder. OTJR (Thorofare N J). 2016;36(2):55–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Report to Congress: Young Adults and Transitioning Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder. October 2017. Retrieved from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2017AutismReport.pdf (accessed January29, 2020)

- 10. McDonald KE, Raymaker DM. Paradigm shifts in disability and health: Toward more ethical public health research. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):2165–2173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chapman DW, Carter J. Translation procedures for the cross cultural use of measurement instruments. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 1979;1:71–78 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Durán LK, Wackerle-Hollman AK, Kohlmeier TL, Brunner SK, Palma J, Callard CH. Individual growth and development indicators-Español: Innovation in the development of Spanish oral language general outcome measures. Early Child Res Q. 2019;48:155–172 [Google Scholar]

- 13. McDonald KE, Conroy NE, Kim CI, LoBraico EJ, Prather EM, Olick RS. Is safety in the eye of the beholder? Safeguards in research with adults with intellectual disability. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2016;11(5):424–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Israel BA, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A, Allen AI, Guzman J. Critical issues in developing and following community based participatory research principles. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, eds. Community Based Participatory Research for Health. San Fransisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003;53–76 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, McDonald K, et al. Collaboration strategies in nontraditional community-based participatory research partnerships: Lessons from an academic-community partnership with autistic self-advocates. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2011;5(2):143–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, Kapp SK, et al. The AASPIRE practice-based guidelines for the inclusion of autistic adults in research as co-researchers and study participants. Autism. 2019;23(8):2007–2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, McDonald K, et al. Comparison of healthcare experiences in autistic and non-autistic adults: A cross-sectional online survey facilitated by an academic-community partnership. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(6):761–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nicolaidis C, Kripke CC, Raymaker D. Primary care for adults on the autism spectrum. Med Clin North Am. 2014;98(5):1169–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nicolaidis C, Raymaker DM, Ashkenazy E, et al. “Respect the way I need to communicate with you”: Healthcare experiences of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism. 2015;19(7):824–831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, McDonald K, et al. The development and evaluation of an online healthcare toolkit for autistic adults and their primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(10):1180–1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Raymaker DM, McDonald KE, Ashkenazy E, et al. Barriers to healthcare: Instrument development and comparison between autistic adults and adults with and without other disabilities. Autism. 2017;21(8):972–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kidney CA. Involvement in the online autistic community, identity, community, and well-being. Dissertations and Theses 2012 (Paper 627):10.15760/etd.15627. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1626&context=open_access_etds (accessed January29, 2020)

- 23. Platt L, Powers L, Leotti S, et al. The role of gender in violence experienced by adults with developmental disabilities. J Interpers Violence. 2017;32(1):101–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hughes RB, Robinson-Wellen S, Raymaker D, et al. The relationship of interpersonal violence to physical and psychological health in adults with developmental disabilities. Disabil Health. 2019 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25. Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, Katz M, et al. Community-based participatory research to adapt health measures for use by people with developmental disabilities. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2015;9(2):157–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oschwald M, Leotti S, Raymaker D, et al. Development of an audio-computer assisted self-interview to investigate violence and health in the lives of adults with developmental disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2014;7(3):292–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Raymaker D, Kapp SK, McDonald K, Weiner M, Ashkenazy E, Nicolaidis C. Development of the AASPIRE Web Accessibility Guideline for autistic web users. Autism Adulthood. 2019;1(2):146–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Raymaker DM. Reflections of a community-based participatory researcher from the intersection of disability advocacy, engineering, and the academy. Action Res. 2017;15(3):258–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Raymaker D, Nicolaidis C. Participatory research with autistic communities: Shifting the system. In: Davidson J, Orsini M, eds. Worlds of Autism. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 2013;169–188 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D. Community based participatory research with communities defined by race, ethnicity, and disability: Translating theory to practice. In: Bradbury H, ed. The Sage Handbook of Action Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, LTD; 2015;167–178 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jivraj J, Sacrey L-A, Newton A, Nicholas D, Zwaigenbaum L. Assessing the influence of researcher–partner involvement on the process and outcomes of participatory research in autism spectrum disorder and neurodevelopmental disorders: A scoping review. Autism. 2014;18(7):782–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wright CA, Wright SD, Diener ML, Eaton J. Autism spectrum disorder and the applied collaborative approach: A review of community based participatory research and participatory action research. J Autism. 2014;1(1):1 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, Croen LA, et al. Measuring autistic adults' healthcare self-efficacy, visit preparedness, and use of accommodations. Annual Meeting of the International Society of Autism Research. Montreal, Canada, May 1–4, 2019

- 34. Cassidy S, Bradley L, Bowen E, Wigham S, Rodgers J. Measurement properties of tools used to assess depression in adults with and without autism spectrum conditions: A systematic review. Autism Res. 2018;11(5):738–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cassidy SA, Bradley L, Bowen E, Wigham S, Rodgers J. Measurement properties of tools used to assess suicidality in autistic and general population adults: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;62:56–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McConachie H, Mason D, Parr JR, Garland D, Wilson C, Rodgers J. Enhancing the validity of a quality of life measure for autistic people. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48:1596–1611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McConachie H, Wilson C, Mason D, et al. What is important in measuring quality of life? Reflections by autistic adults in four countries. Autism Adulthood. 2020;2(1):4–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Griffiths S, Allison C, Kenny R, Holt R, Smith P, Baron-Cohen S. The Vulnerability Experiences Quotient (VEQ): A study of vulnerability, mental health and life satisfaction in autistic adults. Autism Res. 2019;12(10):1516–1528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sanmartin C, Berthelot J-M, Ng E, et al. Comparing health and health care use in Canada and the United States. Health Aff. 2006;25(4):1133–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pleis JR, Lucas JW. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2007. Vital Health Stat. 2009:1–159 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. CDC. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS)—Adult access to health care & utilization. 2007. http://www.ihis.us/ihis/resources/surveys_pdf/survey_form_ih2007_fam.pdf Accessed October10, 2012

- 42. Cantor D, Covell J, Davis T, Park I, Rizzo L Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) 2007 final report. 2009; http://hints.cancer.gov/docs/HINTS2007FinalReport.pdf Accessed May18, 2016

- 43. Collins KS; the Commonwealth Fund. Diverse Communities, Common Concerns: Assessing Health Care Quality for Minority Americans: Findings from the Commonwealth Fund 2001 Health Care Quality Survey. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Hobbs M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4(6):256–262 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lorig K, Stewart A, Ritter P, Gonzalez V, Laurent D, Lynch J. Outcome Measures for Health Education and Other Health Care Interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kidney CA, Raymaker D, McDonald K, Boisclair C, Nicolaidis C. Participation in online communities: Exploring the impact of accessible communication. Paper presented at: Society for Disability Studies 2010, Philadelphia, PA

- 47. Gill CJ. Four types of integration in disability identity development. J Vocat Rehabil. 1997;9(1):39–46 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chavis D, Lee K, Acosta J. The sense of community (SCI) revised: The reliability and validity of the SCI-2. Paper presented at: 2nd International Community Psychology Conference, Lisboa, Portugal; 2008

- 49. Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57(6):1069 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: Validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(2):258–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nosek MA, Hughes RB, Petersen NJ, et al. Secondary conditions in a community-based sample of women with physical disabilities over a 1-year period. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(3):320–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Seekins T, White G, Ravesloot C, et al. Issues in disability & health: The role of secondary conditions & quality of life. In: Simeonsson RJ, McDevitt LN, eds. Issues in disability & health: The role of secondary conditions & quality of life. NC Office on Disability and Health, 1999

- 53. Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: Criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(15):1701–1704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper Presented at: 9th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 56. Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behav Res Ther. 1996;34(8):669–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan SO, ed. The Social Psychology of Health: Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE; 1988;31–67 [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Robinson-Whelen S, Hughes RB, Taylor HB, Hall JW, Rehm LP. Depression self-management program for rural women with physical disabilities. Rehabil Psychol. 2007;52(3):254–262 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mayfield D, McLeod G, Hall P. The CAGE questionnaire: Validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131(10):1121–1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, Kivlahan DR. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(7):1208–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Curry MA, Renker P, Hughes RB, et al. Development of measures of abuse among women with disabilities and the characteristics of their perpetrators. Violence Against Women. 2009;15(9):1001–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rodgers J, Farquhar K, Mason D, et al. Development and Initial Evaluation of the Anxiety Scale for Autism — Adults (ASA-A). Autism Adulthood. 2020;2(1):24–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]