Abstract

The role of transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME) in minimally invasive proctectomy, especially rectal cancer surgery, is increasing. There has been exponential growth in uptake from the initial in vivo case in 2010 to the present day. Early adopters of taTME are well within the mature portions of their learning curve, but there are a significant number of novice taTME surgeons. We have overviewed the critical aspects of patient selection, operating room set-up, and necessary equipment. In particular, we recommend that a one-team approach is used for the early cases, and ideally with an experienced proctor. The important technical pearls that will aid the novice taTME surgeon were also described.

Keywords: transanal total mesorectal excision, rectal cancer, patient selection, operating room set up, equipment, one-team approach, pearls

Minimizing risk and complications, while optimizing the chance of successful outcome, is critical to any surgeon performing a new technique. Transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME) provides a unique approach to rectal dissection in a “down to up” fashion while generating high-quality mesorectal specimens and impressive early outcomes in phase 2 and registry studies. 1 However, the change in perspective to the anatomy of the pelvis and distal anorectum has also led to the development of complications unique to this surgical approach including the infamous urethral injury. 2 3 Unfamiliarity with new surgical planes, in addition to the distinctive effects of pneumodissection can lead even the most experienced surgeons astray. Appropriate patient selection including consideration of different rectal pathologies, as well as appreciation of variations in pelvic morphology is important. Furthermore, one must consider a one-team versus two-team approach, or whether to begin with an abdominal approach or a perineal approach. At minimum, surgeons should be expected to have consulted with their hospital guidelines and have taken a formal course with didactic and cadaveric training, prior to developing taTME into clinical practice. 4 Video and/or case observation alone is insufficient. Simulation, or team training as well as proctorship should also be strongly considered. Lastly, despite all preparations prior to the first case, one should still proceed cautiously. An audit of our North American structured training course in North America revealed the risk of iatrogenic injury remains high in early practice suggesting this pathway alone is insufficient. 4 5 6

Patient Selection

TaTME naturally evolved to improve access and surgical precision to the extraperitoneal rectum. Bulky or distal rectal tumors, especially those found in the narrow pelvis of an obese male, pose substantial challenges to conventional approaches to TME and sphincter preservation. Although intuitively, this is the clearest indication for a transanal approach, it is these same patients, which likely pose the most risk for urethral injury, especially those requiring an open intersphincteric approach. As with the traditional TME through an abdominal approach, a female pelvis is frankly easier.

Careful evaluation of the preoperative MRI is imperative. In addition, to tumor height and circumferential resection margin, appraisal of the anal canal height, the posterior anorectal angle, and degree of sacral curvature are important variables to note as well with the taTME approach. Tumor height above the anorectal ring, best measured on coronal and then sagittal images, can be used to accurately determine the initial transanal approach used ( Fig. 1 ). Generally, when the distal edge of the tumor lies greater than 2 cm from the anorectal ring, one can perform the technically easier approach whereas the transanal platform can be placed into the rectum and a purse-string placed endoluminally.

Fig. 1.

Identification of the distal edge of the tumor on coronal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can facilitate planning of the transanal surgical approach.

In our practice, taTME has also been used extensively for benign indications including endometriosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and familial adenomatous polyposis, where proctectomy with reestablishment of bowel continuity is desired. However, those with extensive proctitis or transmural inflammation may pose surgical challenges. Similarly, removal of a retained rectum following total colectomy with or without abdominal assistance is an ideal candidate for initial experience. However, ease of dissection is often proportionate to the duration of diversion and degree of inflammation. Although patients with T4 tumors invading into prostate or vagina have been safely performed, they should be avoided as initial cases.

Room Set-Up/Instrumentation

TaTME is a complex procedure that requires careful thought regarding patient positioning, operating equipment, and set-up. All patients undergoing this procedure should be positioned in supine lithotomy with arms tucked and Allen stirrups. Care much be taken to ensure that the patient's perineum is accessible and will not slide cephalad during the procedure as steep Trendelenburg is required. This can be achieved by use of the Pink Pad (Xodus Medical, New Kensington, PA), or with a vacuum-sealed beanbag. The room set-up should be identical regardless of the single- or two-team approach ( Fig. 2 ). The abdominal team is positioned on the patient's right side, and the transanal team between the legs. Monitors are required on both sides of the patient for the abdominal team, as well as at the head of the bed for the transanal team. In the majority of cases, the abdominal team will remain along the patient's side for the entirety of the procedure, but occasionally the surgical assistant is required to transition to the patient's left side for the rectal dissection from the abdominal approach to avoid obscuring the view of the transanal team. The abdominal scrub nurse and instrument table is usually positioned on the patient's right side, and the transanal scrub nurse and instrument table positioned on the patient's left side behind the transanal operating team. Ideally, the abdominal and transanal towers that contain the video equipment, insufflators, and energy devices should be positioned on opposite sides of the patient to avoid cluttering and to allow for ease of movement of the abdominal team; however, this may not be feasible for operating rooms with integrated booms. No additional specialized equipment is required for the abdominal dissection during a taTME. However, there are several important pieces of equipment that are necessary for the transanal portion ( Table 1 ).

Fig. 2.

Operating room setup for two-team synchronous transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME).

Table 1. Equipment that are necessary for the transanal portion.

| Operating platform | There are several transanal operating platform options (discussed below). The choice should be based on surgeon preference and availability, although the largest experience has been with a flexible platform |

| Camera | A high-definition camera with a 30- or 45-degree scope is recommended. The flexible tip EndoEye Flex (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) may also be used and allows for the camera head and scope to be away from the in-line operating instruments |

| Insufflator | A high-flow insufflator is recommended. The most commonly used is the AirSeal (ConMedm Utica, NY, US), although other high-flow insufflators can be used, such as the TEM high-flow insufflator (Richard Wolf GmbH, Knittlingen, Germany) or the PneumoClear (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI). These high-flow insufflators minimize the bellowing that is associated with standard insufflators, and also provide continuous smoke evacuation. However, the inclusion of the Insufflation Stabilization Bag with the GelPOINT Path (Applied Medical, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA) may provide adequate performance with a standard insufflator |

| Energy device | A bipolar energy device is generally not required during the transanal dissection, especially as the dissection should remain within the avascular TME plane. A monopolar hook cautery with integrated suction is ideal; however, the handle of these instruments may be bulky and may cause significant “knocking” of handles. A hook cautery is recommended over the needle tip as there may be certain portion where retraction and tissue tension may not be adequate |

| Miscellaneous | The choice of the laparoscopic retracting instrument can be left to the surgeon's discretion. Generally, this instrument should have a blunt tip to avoid injury to the mesorectal envelope during retraction, nor should the tips be too long to increase range of motion A Lone Star retractor (Cooper Surgical, Trumbull, CT) is often required for low lesions to evert the anal canal and allow for open placement of the purse-string. This is not generally required for higher lesions where the purse-string is placed endoscopically |

Abbreviations: TEM, transanal endoscopic microsurgery; TME, total mesorectal excision.

Single-Team versus Two-Team Approach

Early in the development of taTME, the two-team, synchronous approach was developed by Professor Antonio Lacy. 7 In early outcomes, the synchronous approach, with surgeons simultaneously operating from both abdominal and perineal fields, has been demonstrated to significantly decrease operative time. Although attainable with experience, there are many subtleties to choreographing two separate operative teams and can provide unique challenges for the novice. In addition, the quantity of personnel required can be prohibitive in many hospitals.

To the contrary, for the beginner taTME surgeon, we recommend a single-team approach. A similarly trained cosurgeon or assistant is imperative in helping to avoid pitfalls. Still, one must decide whether to initiate the surgery abdominally or transanally. An abdominal approach may provide a surgeon with the familiarity of traditional TME. Left colon mobilization and dissection of the upper rectum is performed first up to the peritoneal reflection or until retraction becomes difficult. The transanal portion is then performed and communicated with the abdominal plane. Alternatively, following laparoscopic evaluation to assure there is no evidence of peritoneal disease, surgery can be initiated transanally with dissection continuing until entry into the peritoneal cavity, followed by an abdominal approach for colon mobilization. The transanal approach permits early identification of a safe distal margin, and places immediate concentration on precise dissection of the low and mid rectum. More importantly, it mandates the apprentice taTME surgeon focus on mastery of the critical unique steps including an endoluminal purse-string, proctotomy, and subsequently the intricacies of the surgical planes from this perspective. In cases of laparoscopic TME with intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer, the primary perineal approach appears to reduce operative time and is associated with similar short- and long-term outcomes as compared with the primary abdominal approach. 8 The International taTME Registry also exhibits an increasing trend toward two-team synchronous surgery with decreasing operative times. 1 Therefore, we recommend a single-team approach, with primary transanal approach until adequate experience and maturation are achieved prior to pursuing two-team surgery.

Transanal Platform: Rigid or Flexible

At the same time the first taTME was performed with the use of a rigid transanal platform, transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS), and the first flexible transanal platform (GelPOINT Path, Applied Medical, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA) were in development. The subsequent rapid uptake of taTME was facilitated by the access and easy usability of the flexible channel; in fact, the current technical steps in which taTME is performed and taught is a direct reflection of the device with which it organically evolved and became standardized. More than 80% of taTME surgeries recorded in the taTME registry have been performed with the flexible platform. 1

In a recent comparative analysis between transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) and TAMIS, our group demonstrated that the two platforms were equivalent with identical rates of margin positivity, local recurrence, and peritoneal entry. 9 However, the operative times were significantly longer when the rigid platform (TEM) was used, almost certainly related to prolongation of the setup time. This is certainly reproduced if not aggravated with taTME. After initial fixation to the patient bed and within the anorectum, the rigid platform requires continuous adjustments as the dissection is advanced up the pelvis. This can be time consuming for even the most experienced TEM/transanal endoscopic operation surgeons. The simplicity of the flexible port insertion, just above the anal canal with quick access to the distal mesorectum, with comparable ergonomics clearly favors its use.

On the other hand, both platforms are capable of producing precise high-resolution access to the distal rectum, with stable pneumorectum permitting precise dissection required for mesorectal excision. Surgeons who perform high-volume local excision and are extremely proficient with the use of the rigid platform will not unexpectedly appreciate its familiarity while acquiring the nuances of taTME. In addition, use of the rigid platform for those who have already made a capital investment, is extremely cost effective, eliminating the expense of a disposable port. 10

Many options for both reusable and disposable flexible platforms now exist in different sizes with expanding features. Additionally, the standard rigid platforms continue adapting to the advancing field of transanal surgery. Unfortunately, in many countries and hospitals, cost and access may be the single determinant. Whichever platform is chosen, we unequivocally recommend that the surgeon perform cadaveric training, with the same setup with which they plan on operating.

Technical Tips

TaTME is a complex procedure and should be reserved for those who already have an expertise in minimally invasive rectal cancer surgery as well as local excision via transanal endoscopic surgery. 5 6 There are several important technical pearls that can facilitate all surgeons performing taTME, in particular those in the early portion of their learning curve.

Purse-string : The initial purse-string is first and one of the most important elements of taTME, as this will immediately define the distal margin. In addition, it permits early washout of the distal rectum with betadine while maintaining a sterile and sealed area to produce pneumatic distention. Although more technically demanding, we encourage early learning and application of the endoluminally placed purse-string. However, the purse-string can also be performed in “open” fashion, through the operating channel, with a traditional winged anorectal retractor, or through disposable operating anoscopes. Endoscopic placement requires insufflation of the bowel, which can cause colonic distension and may impede the abdominal dissection. The upper rectum should be occluded with a laparoscopic instrument during the entirety of purse-string placement to avoid this. Further unwanted colonic distention should make the abdominal surgeon immediately aware of an incompletely secured purse-string below ( Fig. 3 ). Prior to purse-string placement, we mark the rectum with cautery to plan its exact placement and avoid spiraling. We use a 2–0 Prolene suture and start the purse-string approximately 0.5 to 1 cm below the lower edge of the tumor at the 4 to 5 o'clock position. The suture can be placed as high as one would like in the rectum, as ultimately the distal margin is determined by the location of proctotomy.

Fig. 3.

Distention of the colon or rectum should immediately alarm the abdominal surgeon to an incompletely closed purse-string.

In cases with tumors within 2 cm to the anorectal ring, an intersphincteric dissection is begun without the operating port, and the rectum closed with a running suture once there is enough free edge to do so. This is generally done once the intersphincteric dissection reaches or extends past the anorectal ring (the operating port is then placed into the anal canal afterwards). The purse-string should optimally be seromuscular and not full-thickness to avoid inadvertently pulling surrounding structures into the rectal wall (such as the endopelvic fascia overlying the levator muscles, or vagina). This is common for very low tumors and will make identifying the correct plane and circumferential dissection more difficult. Care must also be taken to place bites symmetrically to avoid excessive bunching of the rectal wall when the purse-string is tied down ( Fig. 4 ). This will make the proctotomy subsequently more difficult if there are large folds to cut through. Finally, the purse-string should be airtight to allow for optimal pneumorectum and avoid distension of the abdominal colon, as well as prevent spillage of tumor cells or colonic contents into the operative field. Multiple knots should be tied to provide a “handle” for retraction and avoid breaking the purse-string.

Fig. 4.

The purse-string should be performed evenly to avoid bunching and asymmetry.

For higher lesions, an endoscopic purse-string is performed in similar fashion. We recommend leaving the suture long and placing a snap at the free end outside of the operating platform to create some tension along the suture and avoid an excessive amount of loose suture within the rectal lumen. Once the purse-string is complete, a knot pusher can be used to tie down the purse-string, or for a simpler method, the cap can be removed and the knot tied conventionally. Endoluminal knot tying is very technically demanding within the confined space of the rectal lumen, especially with the tension required to close the purse-string airtight. An inadvertently damaged purse-string or one not closed tight enough should be immediately repaired. Again, the easiest repair is to open the cap, grasp the suture with forceps and retract distally, and place a single figure-of-eight suture.

Proctotomy : Once the purse-string is completed, the next important step is the circumferential full-thickness proctotomy. We recommend that the proposed line of incision is again marked using the cautery device prior to starting the proctotomy. These marks should be placed at least 1 cm away from the purse-string itself and is generally recommended to be placed outside of the mucosal folds ( Fig. 5 ). This generates an adequate distal margin and reinforces the importance of a properly created purse-string. Tension should be created by retracting the knots of the purse-string. The surgeon must be aware that the rectal wall is quite thick and must ensure that the proctotomy is complete before the dissection continues cephalad to avoid dissection within the rectal tube. We generally start in the anterior midline, as this is where the mesorectum is the thinnest and correct TME plane can be immediately found once the rectal wall is transected completely ( Fig. 6 ). It is also important to be aware that the rectal wall should be cut perpendicularly, and that an oblique transection line can be easily done due to the pneumorectum “pushing out” the rectal lumen. 11 If a hook cautery is used, the tip of the hook should be placed to create a “U” between the longitudinal muscle fibers and the L-hook, and the instrument rotated 90 degrees to “hook” the rectal wall. This technique facilitates perpendicular proctotomy. Once the rectal wall is fully transected in the anterior midline, the remaining circumferential proctotomy is easily performed.

Fig. 5.

The proctotomy should be marked distal to the purse-string on the flattened portion of the rectum if possible, to avoid cutting through the mucosal folds, or inadvertently cutting the purse-string.

Fig. 6.

The anterior midline is the easiest place to start the dissection and divide through the rectal wall.

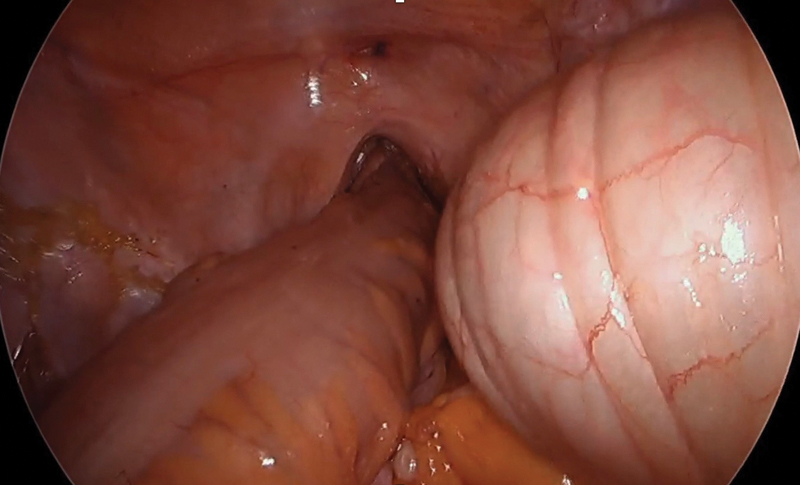

Maintaining the correct plane : Once the proctotomy is completed with identification of the correct plane of dissection anteriorly, we recommend finding the plane at the 4 o'clock or 8 o'clock position and then working clockwise to the other side ( Fig. 7 ). The anterolateral positions are left for the end as these generally represent the most difficult areas to identify the correct plane. Anteriorly, the posterior surface of the prostate or vagina clearly delineates the correct plane, and there is minimal mesorectum at this level, which makes identifying the correct TME plane simpler. Starting the proctotomy and TME dissection in males also immediately identifies the posterior surface of the prostate, which will ensure the prostate is not inadvertently dissected into the specimen and avoid urethral injuries. Similarly, the 4 o'clock position is delineated laterally by the endopelvic fascia that envelopes the pelvic floor muscles. This fascia should be left on the muscles, and contraction of the pelvic floor or exposure of bare muscle at this level alerts the surgeon that the plane of dissection is too deep ( Fig. 8 ). The mesorectum is thickest in the posterior midline, especially if taTME is performed for higher tumors. Care must also be taken to transect the mesorectum perpendicularly to the proctotomy to avoid coning. Once the correct anterior and posterolateral planes of dissection are identified, the anterolateral areas are dissected. As with TME from an abdominal approach, the plane in this location is the most challenging to visualize. In males, these positions contain the seminal vesicles and the neurovascular bundles of Walsh. 3 When dissection is performed too lateral, and inside the endopelvic fascia at this level, a distinct ovoid of fatty tissue remains and is one of the most obvious clues to an incorrectly deep dissection plane ( Fig. 9 ). Encountering bleeding at these levels further signifies that the dissection plane is too deep and should be corrected.

Fig. 7.

Once the proctotomy is performed and the rectal wall detached, we recommend locating the mesorectum at the 4 or 8 o'clock positions.

Fig. 8.

Exposure of the bare levator muscle in the posterolateral positions should alert the operating surgeon that he is deep into the endopelvic fascia.

Fig. 9.

( A ) Identification of the distinctly different ovoid of fat anterolaterally (marked with *) and just behind the peritoneal reflection is one of the most obvious visual clues to a deep dissection. ( B ) The correct dissection plane is noted medially by arrows.

It is also important to ensure that the TME dissection is performed circumferentially at equal extent and not carried too far in any one quadrant. If this is done, the pneumorectum will push the specimen away and distort the contralateral planes. One must also be always conscious of the importance of proper retraction. The correct plane of dissection can be conceptualized as “triangles” and “O's.” 12 Encountering an “O” sign during dissection signifies a new plane has been breached. Although this may indicate the proper plane, during taTME this is more commonly noted with incursion into an abnormal plan. In addition, single-instrument proper retraction produces the formation of triangles in the tissue ( Fig. 10 ). The dissection should be performed along the tips of the triangles and not at the base.

Fig. 10.

The identification of an “O” should alert the surgeon a plane has been entered. Similarly, proper retraction will produce triangles, which can guide the surgeon into the correct plane.

How far to go? : It is generally recommended to continue the circumferential TME dissection cephalad until the peritoneal reflection anteriorly, and to approximately the level of S3 posteriorly. It is at this level that the sacrum usually changes angle abruptly which makes adequate retraction and visualization difficult from the transanal approach. Furthermore, there is no obvious advantage to proceeding beyond this level from below, as the abdominal dissection is generally performed without much difficulty to this level. If a two-team approach is used, the abdominal and transanal planes of dissection are usually connected at the S3 level posteriorly and at the peritoneal reflection anteriorly. Once the planes are connected, either team can retract for the other and facilitate completion of the circumferential dissection. This is especially important at the positions of the seminal vesicles where the correct planes of dissection are often not as obvious as the rest of the TME.

Anastomotic details : Once the TME dissection is completed, the specimen can be exteriorized through the anus or through an abdominal incision. We have trended away from transanal excision unless a hand-sewn coloanal anastomosis is planned. This avoids overmanipulation and trauma to the intended colonic conduit and sphincter complex with transanal extraction. As anastomotic techniques are discussed in a separate chapter, we will only describe tips for our preferred method of transanal anastomosis.

Extraction through a Pfannenstiel incision, as this has had the lowest incidence of short- and long-term morbidity in our experience. 13 For stapled anastomosis, the access channel is left in place and the cap of the GelPOINT Path is removed to create the purse-string “open.” A running “baseball” stitch is performed using 2–0 Prolene beginning in the posterior midline from outside to in. At the anterior midline the suture is reversed to continue suturing forehand and to end the suture on the outside. The knot is then tied down with the sleeve still in place, and the sutures left long as a handle and pulled in as the anvil is tightened. It is impossible to secure the purse-string completely tight, and a small opening will always persist. The access channel, while retained in place, stents the sphincter complex open and permits easier placement and manipulation of any circular stapler between 25 and 32 mm. Unlike with conventional anastomosis, the spike on a circular stapler is extended completely and easily placed through the central opening, especially when illuminated with a laparoscope. The proximal anvil is then mated under direct vision and the anastomosis is created. We attempt, whenever possible, to create a side-to-end or colonic J-pouch for low anastomoses to improve function 14 however, is not always feasible. Alternative techniques for anastomotic creation include guiding the proximal anvil through the rectal purse-string directly, prior to securing the purse-string. This allows easy transanal mating of the circular stapler, but can be more challenging during the initial cases; hence, the increased utilization of longer anvil staplers. While early in ones taTME experience, we recommend an abdominal extraction, with an anastomosis performed according to comfort level. Perhaps, the best early indication may be in patient not a candidate for sphincter preservation, however, not one requiring abdominal perineal resection, as this has its own complexities.

Conclusion

The role of taTME in minimally invasive proctectomy, especially rectal cancer surgery, is increasing. There has been exponential growth in uptake from the initial in vivo case in 2010 to the present day. Early adopters of taTME are well within the mature portions of their learning curve, but there are a significant number of novice taTME surgeons. We have overviewed the critical aspects of patient selection, operating room set-up, and necessary equipment. In particular, we recommend that a one-team approach is used for the early cases, and ideally with an experienced proctor. The important technical pearls that will aid the novice taTME surgeon were also described.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Dr. Albert reports personal fees from Applied Medical, personal fees from Stryker Medical, personal fees from Conmed, personal fees from Cooper Surgical, personal fees from Human Extensions, outside the submitted work.

References

- 1.Penna M, Hompes R, Arnold S et al. Transanal total mesorectal excision: international registry results of the first 720 cases. Ann Surg. 2017;266(01):111–117. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atallah S, Albert M, Monson J R. Critical concepts and important anatomic landmarks encountered during transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME): toward the mastery of a new operation for rectal cancer surgery. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20(07):483–494. doi: 10.1007/s10151-016-1475-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atallah S, Albert M. The neurovascular bundle of Walsh and other anatomic considerations crucial in preventing urethral injury in males undergoing transanal total mesorectal excision. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20(06):411–412. doi: 10.1007/s10151-016-1468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atallah S B, DuBose A C, Burke J P et al. Uptake of transanal total mesorectal excision in North America: initial assessment of a structured training program and the experience of delegate surgeons. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(10):1023–1031. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francis N, Penna M, Mackenzie H, Carter F, Hompes R; International TaTME Educational Collaborative Group.Consensus on structured training curriculum for transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME) Surg Endosc 201731072711–2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penna M, Hompes R, Mackenzie H, Carter F, Francis N K. First international training and assessment consensus workshop on transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME) Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20(06):343–352. doi: 10.1007/s10151-016-1454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arroyave M C, DeLacy F B, Lacy A M. Transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME) for rectal cancer: step by step description of the surgical technique for a two-teams approach. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(02):502–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanso F, Maggiori L, Debove C, Chau A, Ferron M, Panis Y. Perineal or abdominal approach first during intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer: which is the best strategy? Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(07):637–644. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee L, Edwards K, Hunter I A et al. Quality of local excision for rectal neoplasms using transanal endoscopic microsurgery versus transanal minimally invasive surgery: a multi-institutional matched analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(09):928–935. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maslekar S, Pillinger S H, Sharma A, Taylor A, Monson J R. Cost analysis of transanal endoscopic microsurgery for rectal tumours. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9(03):229–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atallah S, Gonzalez P, Chadi S, Hompes R, Knol J. Operative vectors, anatomic distortion, fluid dynamics and the inherent effects of pneumatic insufflation encountered during transanal total mesorectal excision. Tech Coloproctol. 2017;21(10):783–794. doi: 10.1007/s10151-017-1693-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernardi M P, Bloemendaal A L, Albert M, Whiteford M, Stevenson A R, Hompes R. Transanal total mesorectal excision: dissection tips using ‘O's and ’triangles'. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20(11):775–778. doi: 10.1007/s10151-016-1531-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee L, Abou-Khalil M, Liberman S, Boutros M, Fried G M, Feldman L S. Incidence of incisional hernia in the specimen extraction site for laparoscopic colorectal surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(12):5083–5093. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5573-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown C J, Fenech D S, McLeod R S. Reconstructive techniques after rectal resection for rectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(02):CD006040. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006040.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]