Abstract

Gait variability is generally associated with falls, but specific connections remain disputed. To reduce falls, we must first understand how older adults maintain lateral balance while walking, particularly when their stability is challenged. We recently developed computational models of lateral stepping, based on Goal Equivalent Manifolds, that separate effects of step-to-step regulation from variability. These show walking humans seek to strongly maintain step width, but also lateral position on their path. Here, 17 healthy older (ages 60+) and 17 healthy young (ages 18–31) adults walked in a virtual environment with no perturbations and with laterally destabilizing perturbations of either the visual field or treadmill platform. For step-to-step time series of step widths and lateral positions, we computed variability, statistical persistence, and how much participants directly corrected deviations at each step. All participants exhibited significantly increased variability, decreased persistence, and tighter direct control when perturbed. Simulations from our stepping regulation models indicate people responded to the increased variability imposed by these perturbations by either maintaining or tightening control of both step width and lateral position. Thus, while people strive to maintain lateral balance, they also actively strive to stay on their path. Healthy older participants exhibited slightly increased variability, but no differences from young in stepping regulation and no evidence of greater reliance on visual feedback, even when subjected to substantially destabilizing perturbations. Thus, age alone need not degrade lateral stepping control. This may help explain why directly connecting gait variability to fall risk has proven difficult.

Keywords: Lateral Balance, Older Adults, Stepping, Foot Placement, Multi-Objective Control

INTRODUCTION

Over 25% of older adults (age ≥ 65) fall each year, often resulting in injury and increased morbidity and mortality (Bergen et al., 2016). Falls are difficult to predict because they result from many intrinsic and extrinsic factors, including age-related physical and/or cognitive deficits and/or environmental challenges to stability (Fischer et al., 2014; Robinovitch et al., 2013). Since most falls occur while walking (Kelsey et al., 2012), changes in how older adults regulate their stepping movements from step-to-step may affect their fall risk.

Older adults typically exhibit increased gait variability (Kang and Dingwell, 2008b) that is associated with fall history (Toebes et al., 2012), but may or may not predict future falls (Paterson et al., 2011; Verghese et al., 2009). Likewise, experimental findings vary widely as to which increases in variability of which stepping variables contribute to falls (Brach et al., 2005; Moe-Nilssen and Helbostad, 2005; Owings and Grabiner, 2004). Further, the causes of this variability remain unclear. Variability likely results partly from increased physiological noise (Christou, 2011) that may be detrimental (Roos and Dingwell, 2010; Taylor et al., 2013). Conversely, people also purposefully adjust foot placement at each step (Matthis et al., 2017) to maintain balance (Macdonald, 2009; Oddsson et al., 2004), introducing variability that may be beneficial in a changing environment (Twardzik et al., 2019). Indeed, intrinsic redundancy itself contributes to variability (Todorov, 2004). Before we can determine how stepping variability relates to fall risk, we must first determine the extent to which different underlying sources (noise vs. redundancy vs. control) contribute to the variability of which gait variables (e.g., step time, step width, etc.) in what ways (i.e., beneficial or detrimental).

We have developed frameworks that disambiguate the relevance of different stepping variables and the sources of their variability. These frameworks propose goal functions to theoretically define a task and determine the sets of all possible stepping solutions as a Goal Equivalent Manifold (GEM) (John et al., 2016). Applied to the sagittal plane, these GEM-based frameworks demonstrate that humans directly correct deviations in stride speed, but allow fluctuations in stride length and time to persist (Dingwell and Cusumano, 2015; Dingwell et al., 2010). Several studies independently replicated our main predictions (Decker et al., 2012; Roerdink et al., 2015; Roerdink et al., 2019; Terrier and Dériaz, 2012). Importantly, increases in sagittal plane gait variability were not attributed to changes in stepping regulation in healthy older adults (Dingwell et al., 2017).

Understanding lateral stepping regulation is also critical (Bruijn and van Dieën, 2018), as humans are more unstable laterally (McAndrew et al., 2011; O’Connor and Kuo, 2009), and older adults prioritize maintaining lateral balance over energetic cost (Dean et al., 2007). We recently extended our GEM-based framework to identify goal functions for lateral stepping regulation. There, multi-objective control models demonstrate that during unperturbed walking, healthy adults seek primarily to maintain step width, but also to maintain some absolute lateral position on their path (Dingwell and Cusumano, 2019). Here, we apply this new framework to healthy older adults walking both without and with lateral perturbations. This is a critical first step to disambiguate the relevance of different lateral stepping variables and to identify what sources give rise to stepping variability.

Determining how regulating lateral stepping affects lateral balance requires assessing stepping regulation in destabilizing environments. Subjecting participants to lateral perturbations while walking leads to increased variability and local dynamic instability in young and older adults (Francis et al., 2015; McAndrew et al., 2010; McAndrew et al., 2011). While participants in those experiments never actually fell, their risk of falling likely increased, as it would take a much smaller additional perturbation to induce an actual fall (McAndrew et al., 2010), as confirmed by modeling (Roos and Dingwell, 2010; Su and Dingwell, 2007). Thus, to understand how age and challenges to stability may invoke meaningful changes in stepping regulation, it is important to study frontal plane stepping strategies of older adults walking in such destabilizing environments.

Here, we applied destabilizing lateral perturbations to determine how healthy young and older adults alter frontal plane stepping to maintain stability. We applied our GEM-based framework for lateral stepping regulation to quantify gait variability and step-to-step regulation with respect to defined task goals of maintaining step width and lateral body position (Dingwell and Cusumano, 2019). We hypothesized that when walking in destabilizing environments, healthy adults would “tighten” their stepping regulation, increasing priority to maintain step width and/or position. With respect to age, older adults might exhibit greater difficulty maintaining lateral stepping because lateral balance requires greater active control in this population (Dean et al., 2007). Conversely, healthy older adults might instead retain their capacity to regulate lateral stepping despite increased physiological noise (Christou, 2011), as they do for sagittal stepping (Dingwell et al., 2017) and possibly also for lateral stepping (Eckardt and Rosenblatt, 2018). The present study directly tested these competing hypotheses.

METHODS

Participants

Seventeen young healthy (YH) and 19 older healthy (OH) adults initially participated. All participants were screened to ensure their gait was not affected by any cardiovascular, neurological, visual, or musculoskeletal injuries, surgeries or conditions. All participants provided written informed consent, as approved by the University of Texas IRB. Two OH participants used the handrails to maintain balance during walking trials. These participants were excluded from all subsequent analyses, which were conducted on the remaining 17 YH and 17 OH adults (Table 1).

Table 1 –

Young Healthy and Older Healthy Participant Characteristics. All values except Sex are given as Mean ± Standard Deviation. Two-sample t-test (equivalent to a single-factor ANOVA in this case) p-values that indicate significant group mean differences are bolded.

| Characteristic: | Young Healthy (YH): | Older Healthy (OH): | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex [M/F] | 8 / 9 | 7 / 10 | N/A |

| Age [yrs] | 23.7 ± 3.7 | 67.5 ± 4.9 | < 0.001 |

| Body Height [m] | 1.72 ± 0.1 | 1.71 ± 0.1 | 0.772 |

| Body Mass [kg] | 64.5 ± 12.5 | 73.3 ± 18.9 | 0.118 |

| Body Mass Index [kg/m2] | 21.7 ± 3.2 | 24.9 ± 5.4 | 0.042 |

| Leg Length [m] | 0.89 ± 0.05 | 0.90 ± 0.05 | 0.453 |

We measured participants’ body mass, height, leg length, and body mass index. Physical performance assessments included Timed Up and Go (Podsiadlo and Richardson, 1991), Four Square Step Test (Dite and Temple, 2002), average maximum left/right isometric quadriceps strength (Salinas et al., 2017), and preferred overground walking speed (Kang and Dingwell, 2008a). Cognitive assessments included the Mini-Mental State Exam (Folstein et al., 1975) and the 10-point abbreviated Iconographic-Falls Efficacy Scale (Delbaere et al., 2011). Two-sample t-tests assessed differences in participant demographic and assessment characteristics.

Protocol

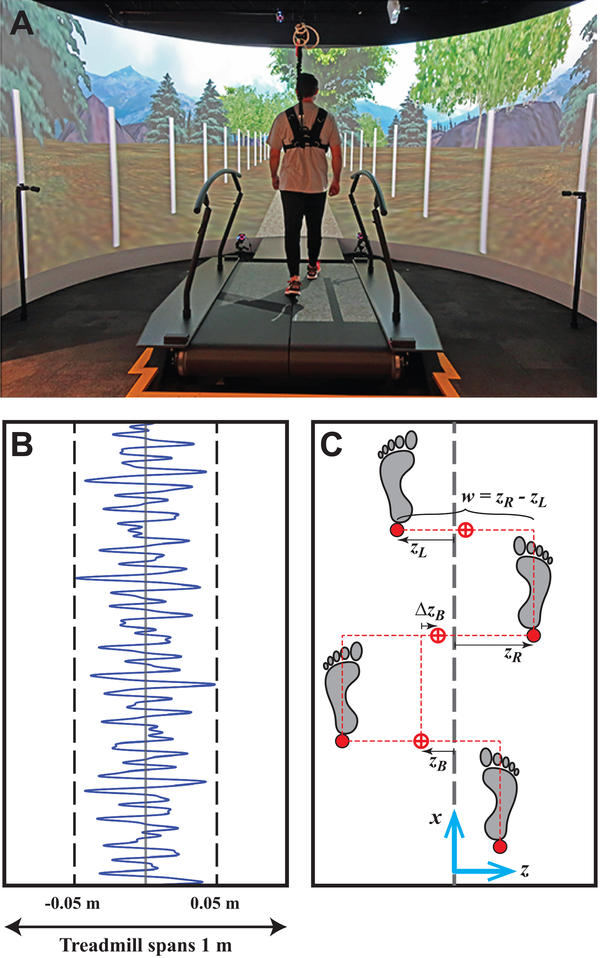

Participants walked in a “V-Gait” virtual reality system (Fig. 1A) that integrates an instrumented treadmill, immersive virtual reality, and motion capture (Motekforce Link, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Participants wore their own comfortable walking shoes throughout. Participants wore a safety harness attached to an external frame and were encouraged not to use available handrails.

Figure 1 –

A) Photo of a typical participant walking in a Motek system that integrates an instrumented treadmill, motion capture, and immersive virtual reality. B) Example sequence of the continuous, pseudorandom oscillations of the treadmill that provided destabilizing perturbations. Visual field oscillations (not shown) used the same pattern. C) Schematic that demonstrates the primary lateral stepping variables that can be regulated from step-to-step (Dingwell & Cusumano, 2019): lateral positions of each foot (zL and zR), absolute lateral body position (zB; proxy for center-of-mass), change in lateral position (ΔzB; proxy for ‘heading’ or lateral speed), and step width (w).

Participants first completed a 3-min acclimation where treadmill speed was gradually increased from 50–90% of their preferred overground walking speed (Table 2). For all subsequent trials, treadmill speed was set to 90%. Forward speed of the visual optic flow was always matched to the treadmill speed. Participants walked under each of 3 conditions: with no perturbations (NOP), or with continuous lateral oscillations of the visual field (VIS) or treadmill platform (PLAT) (McAndrew et al., 2010). Oscillations were pseudorandom to prevent entrainment (Warren et al., 1996), and confined to the lateral direction (O’Connor and Kuo, 2009).

Table 2 –

Young Healthy and Older Healthy Physical and Cognitive Assessment Results. All values are given as Mean ± Standard Deviation. Two-sample t-test (equivalent to a single-factor ANOVA in this case) p-values that indicate significant group mean differences are bolded.

| Assessment: | Young Healthy (YH): | Older Healthy (OH): | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Max. Quad. Strength [N] | 75.1± 23.9 | 75.4 ± 23.9 | 0.520 |

| Timed Up and Go [s] | 8.06 ± 1.20 | 8.66 ± 1.08 | 0.139 |

| Four Square Step Test [s] | 7.18 ± 1.53 | 9.07 ± 2.07 | 0.005 |

| Preferred Overground Walking Speed [m/s] | 1.46 ± 0.15 | 1.35 ± 0.14 | 0.033 |

| Mini Mental State Exam [/30] | 29.2 ± 1.3 | 28.1 ± 2.2 | 0.082 |

| Icon Falls Efficacy Scale [/40] | 13.1 ± 1.5 | 14.9 ± 4.5 | 0.125 |

The order of presentation of conditions was balanced across participants, with all same-condition trials presented consecutively. Participants completed three 3-min trials for each condition. The first trial of each VIS and PLAT condition was an acclimation trial: perturbation magnitudes were gradually increased from 50–100% over the first 2 minutes. Participants rested (≥ 2-min) between trials. Participants were instructed to “try to walk normally and look straight ahead”.

During NOP trials, participants walked with no perturbations. During PLAT trials, the treadmill surface translated pseudorandomly (Fig. 1B) with normal visual optic flow. During VIS trials, the visual field translated pseudorandomly while the treadmill remained stationary. The virtual scene included a path through a forest (Fig. 1A). White posts (2.4 m tall; every 3 m) lined the path to increase motion parallax (Bardy et al., 1996). Medio-lateral perturbations were pseudorandom (Fig. 1B), similar to those used previously (McAndrew et al., 2010):

| (1) |

where D(t) is the lateral translation distance (m), A is a scaling factor and t is time (s). PLAT and VIS oscillations were scaled to amplitudes of A = 0.015 and A = 0.25, respectively.

Motion Capture

Each subject wore 16 retroreflective markers. Four markers each were placed on the head (left and right forehead and backhead), pelvis (left and right Posterior Superior Iliac Spine (PSIS), left and right Anterior Superior Iliac Spine (ASIS)), and on the shoe surface, aligned with various foot landmarks (lateral malleolus, calcaneus, first and fifth metatarsal heads). Four additional markers were placed on the treadmill platform to define a treadmill reference frame. Kinematic data were collected at 120 Hz from a 10-camera Vicon motion capture system (Oxford Metrics, Oxford, UK). Raw data were processed using Nexus (Oxford Metrics, Oxford, UK). Marker trajectories were exported to MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) for further analyses.

Data Analyses

We analyzed only the latter two trials for each condition. Marker trajectory data were first interpolated to 600 Hz to ensure accurate stepping-event detection (Bohnsack-McLagan et al., 2016). To account for the moving treadmill platform during PLAT trials (zTM; Fig. 2), foot kinematics were analyzed in the moving treadmill reference frame.

Figure 2 –

Example time series data for a representative trial of a typical participant for each experimental condition: No Perturbations (NOP), lateral oscillations of the visual field (VIS), and lateral oscillations of the treadmill platform (PLAT). Each plot shows 80 consecutive steps of: left (zL; red) and right (zR; blue) foot placements, step width (w), absolute lateral body position (zB), and position of the treadmill platform (zTM). The position of the treadmill changed only during PLAT condition. For the plots of zL and zR, the black dashed line indicates the center of the treadmill. For the plots of w, the blue dashed line indicates the average step width. For the plots of zB and zTM, the black dashed lines indicate the x-axis (fore-aft) in the lab-based frame.

Each step was defined at heel strike determined using a PSIS-heel maximum distance algorithm (Zeni et al., 2008). For consistency, we analyzed the N=230 consecutive steps following the first 15s of each trial. Lateral (here, z-coordinate; Fig. 1C) placements of the left and right feet for each consecutive step n ∈ {1,⋯,N}, {zLn, zRn}, were defined as the lateral positions of respective heel markers. These {zLn, zRn} define the end effectors that enact regulation of absolute lateral position (zBn) and step width (wn) (Fig. 1C) and are directly related as (Dingwell and Cusumano, 2019):

| (2) |

For each zB and w time series (Fig. 2), we computed means and standard deviations. To quantify how stepping fluctuations were regulated from each step to the next, we computed Detrended Fluctuation Analysis (DFA) scaling exponents (α) for each zB and w time series (Dingwell and Cusumano, 2019; Dingwell et al., 2010). These quantified the amount of statistical persistence in each time series, independent of variability magnitude (Dingwell and Cusumano, 2010). Values of α > ½ indicate statistical persistence, where a deviation of a parameter value is followed by a subsequent deviation in the same direction. Values of α < ½ indicate anti-persistence, where a deviation of a parameter value is followed by a subsequent deviation in the opposite direction. Values of α = ½ indicate uncorrelated deviations, where deviations from step-to-step are attributed to noise. Fluctuations with α ≈ 0.5 are typically exhibited by variables that are more tightly regulated, while fluctuations with α >> ½ (indicating strong persistence) are typically exhibited by variables that are less tightly regulated (Dingwell and Cusumano, 2010, 2019).

DFA analyses capture how much participants adjusted zB and w deviations from each step to the next (Dingwell et al., 2010), but not how each correction depends on the magnitudes of that deviation (Dingwell and Cusumano, 2019). We therefore also performed a direct control analysis of step-to-step corrections (Dingwell and Cusumano, 2015). For q ⊰ {zB, w}, participants attempting to maintain some average exhibit deviations on any given step of . Each such deviation is corrected on the subsequent step with a change in the opposite direction: Δqn+1 =qn+1 – qn. For each time series of zBn and wn, we plotted Δqn+1 vs. q’n (Fig. 3) and computed (via least-squares regression) linear slopes and strength of correlation (R2). We expected that parameters tightly controlled would be corrected quickly, yielding slopes close to –1 and higher R2 (Dingwell and Cusumano, 2015).

Figure 3 –

Example plots for a trial of a typical participant for each of three conditions, including: No perturbations (NOP), oscillations of the visual field (VIS), and oscillations of the treadmill platform (PLAT). These plots show how errors in relative absolute position (zB)n’ and step width (w)n’ were corrected on subsequent strides: Δ(w) and Δ(zB). Each data point represents one step during a trial. Diagonal red lines indicate least-squares fits for each set of data points. Diagonal, dashed black lines indicate “perfect” error correction, at a slope of −1.

Two factor (Age×Condition) mixed-effects-model analyses of variance (ANOVA) tested for differences between means, standard deviations, DFA α exponents, control slopes, and R2 values. Standard deviation variables were first log-transformed to satisfy normality/linearity requirements. When Condition main effects were significant, Tukey’s least significant difference pairwise comparisons were conducted between the relevant Conditions (VIS vs. NOP and PLAT vs. NOP) across both Age groups (YH and OH). When Age×Condition interaction effects were significant, Tukey’s least significant difference pairwise comparisons were conducted separately for Age group differences (YH vs. OH) for each Condition (NOP, VIS, and PLAT) and for the relevant Condition differences (VIS vs. NOP and PLAT vs. NOP) for each Age group (YH and OH). Walking speed was added as a covariate when Age group main effects or Age×Condition interaction effects were significant. Statistical analyses were performed in Minitab (Minitab, Inc. State College, PA).

Multi-Objective Control Simulations

We recently found (Dingwell and Cusumano, 2019) that unperturbed humans use multi-objective control to regulate lateral stepping: they trade-off controlling mostly step width (w) with some lateral position (zB). We performed additional parameter sensitivity analyses (see Supplement) of our model to gain additional insights into the underlying causes of experimental changes observed here. Specifically, we tested three possibilities. First, the external perturbations themselves introduce additional noise into the system. We expected this should increase gait variability, but might not affect control-related variables. To test this hypothesis, we simulated how stepping dynamics would change when we increased only additive noise. Second, when perturbed, participants might simply shift how much they controlled for step width vs. position. To test this hypothesis, we simulated how stepping dynamics would change when we varied only the proportion of w-to-zB control. Lastly, participants might increase their degree of control (Dingwell et al., 2010) over w and/or zB. To test this hypothesis, we simulated how stepping dynamics would change if we increased only the control gains for each (see Supplement for details).

RESULTS

OH participants had slightly higher body mass indexes than YH participants (p = 0.042), but were similar otherwise (Table 1). OH participants took slightly longer to perform the Four-Square Step Test (p < 0.005), and walked slightly slower overground (p = 0.033) than YH participants. Groups did not differ on other assessments (Table 2).

Across all conditions, YH and OH participants exhibited similar mean absolute lateral positions (zB; p = 0.977) and mean step widths (w; p = 0.477) (Fig 4A; Table 3). Both groups took wider steps when perturbed (p < 0.001), but did not alter their positions (p = 0.488). In general, participants exhibited the widest steps for the PLAT condition (p < 0.001). All participants were strongly perturbed by the imposed lateral perturbations, as exhibited by their significantly increased zB and w variability (p < 0.001). This was consistent with prior findings from healthy adults (McAndrew et al., 2010) and persons with amputation (Beurskens et al., 2014). OH participants used slightly more variable step widths (p = 0.0380), particularly in the VIS condition (p = 0.0296), but otherwise exhibited variability similar to YH (Fig 4B; Table 3). Differences in walking speed (when added as a covariate) did not explain differences in variability of zB (p = 0.491) or w (p = 0.563).

Figure 4 –

A) Mean values, B) Standard deviations (σ), and C) DFA scaling exponents (α) of step width (w) and absolute lateral body position (zB) for Young Healthy (YH) and Older Healthy (OH) participants for each experimental condition: NOP, VIS, and PLAT. For (C), the horizontal dashed line at 0.5 indicates uncorrelated statistical persistence (i.e. neither persistent nor anti-persistent). All subplots show summary boxplots indicating the median, 1st and 3rd quartiles, and whiskers extending to 1.5× interquartile range. Values beyond this range are shown as individual data points. Results of corresponding statistical comparisons are provided in Table 3. Asterisks indicate significant group differences.

Table 3 –

Statistical results for differences between Age groups (YH vs. OH) and Conditions (NOP, VIS and PLAT) for the data shown in Fig. 3, including: means, variability (σ), and DFA exponents (α) for step width (w) and lateral position (zB). ANOVA results (F-statistics and p-values) are provided for main effects of Age, Condition, and Age×Condition interaction effects, along with the relevant Tukey’s post-hoc comparisons. Significant differences are indicated in bold.

| Data In | Variable | Age | Condition | Age×Condition | Tukey’s (Age Effects) | Tukey’s (Condition Effects) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fig. 3A | Mean (w) | F(1,32) = 0.52 p=0.478 |

F(2,166) = 39.60 p < 0.001 |

F(2,166) = 1.47 p = 0.233 |

N/A | VIS-NOP: p < 0.001 |

| PLAT-NOP: p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Mean (zB) | F(1,32) = 2.91 p = 0.098 |

F(2,166) = 0.72 p = 0.488 |

F(2,166) = 0.70 p = 0.496 |

N/A | N/A | |

| Fig. 3B | ln [σ (w)] |

F(1,32) = 4.55 p* = 0.041 |

F(2,166) = 701.21 p* < 0.001 |

F(2,166) = 5.64 p = 0.004 |

YH: | |

| VIS-NOP: p < 0.001 | ||||||

| NOP: p = 0.259 | PLAT-NOP: p < 0.001 | |||||

| VIS: p = 0.049 | ||||||

| PLAT: p = 0.917 | OH: | |||||

| VIS-NOP: p < 0.001 | ||||||

| PLAT-NOP: p < 0.001 | ||||||

| ln [σ (zB)] | F(1,32) = 3.42 p* = 0.074 |

F(2,166) = 266.35 p* < 0.001 |

F(2,166) = 4.24 p = 0.016 |

YH: | ||

| VIS-NOP: p < 0.001 | ||||||

| NOP: p = 0.129 | PLAT-NOP: p < 0.001 | |||||

| VIS: p = 0.319 | ||||||

| PLAT: p = 0.997 | OH: | |||||

| VIS-NOP: p < 0.001 | ||||||

| PLAT-NOP: p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Fig. 3C | α (w) | F(1,32) = 0.060 p = 0.801 |

F(2,166) = 104.50 p < 0.001 |

F(2,166) = 1.63 p = 0.199 |

N/A | VIS-NOP: p < 0.001 |

| PLAT-NOP: p < 0.001 | ||||||

| α (zB) | F(1,32) = l.07 p = 0.309 |

F(2,166) = 75.10 p < 0.001 |

F(2,166) = 0.96 p = 0.386 |

N/A | VIS-NOP: p < 0.001 | |

| PLAT-NOP: p < 0.001 | ||||||

In cases where Age×Condition interactions are significant, the main effects results should be considered unreliable and misleading. Tukey’s pairwise comparisons results should be used to draw conclusions about age group differences for each condition, as these account for the effects of the interaction.

Within each condition, OH and YH participants exhibited similar statistical persistence (DFA α) of fluctuations in zB (p = 0.309) and w (p = 0.801) (Fig. 4C; Table 3). For each condition, fluctuations in zB exhibited much stronger statistical persistence (larger α) than fluctuations in w, consistent with (Dingwell and Cusumano, 2019). When perturbed (VIS & PLAT), all participants exhibited significantly decreased (p < 0.001; Table 3) statistical persistence (i.e., smaller α) for fluctuations in both zB and w (Fig. 4C), despite increased variability (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, for PLAT perturbations, the anti-persistence (i.e., α < 0.5) of w fluctuations indicates over-correction typical of less optimal regulation (Dingwell et al., 2010).

For both groups and each condition, step width (w) exhibited steeper correction slopes (closer to −1.0) (Fig. 5A) and higher R2 (Fig. 5B) compared to position (zB), reflecting stronger corrections for w than for zB (Dingwell and Cusumano, 2019). In each condition, OH and YH participants exhibited similar correction slopes and R2 for zB and for w (all p > 0.91) (Fig. 5; Table 4). For PLAT perturbations compared to NOP, both groups exhibited correction slopes that became more negative (closer to −1.0; Fig. 5A) and increased R2 (Fig. 5B) for zB (p < 0.001), but did not change for w (p > 0.58). For VIS perturbations, both groups exhibited w correction slopes that became more negative (closer to −1.0) (p < 0.001), but zB correction slopes that became slightly less negative (closer to 0.0) (p < 0.001) (Fig. 5A), with R2 values also changing accordingly (Fig. 5B; Table 4).

Figure 5 –

A) Boxplots of slopes of least-squares fits for (w)n’ vs. Δ(w)n+1 and (zB)n’ vs. Δ(zB)n+1 for YH and OH groups for all trials for all conditions. The horizontal dashed lines indicate a slope of −1: i.e., “perfect” error correction. B) Boxplots of correlations (R2) of these least-squares fits (w)n’ vs. Δ(w)n+1 and (zB)n’ vs. Δ(zB)n+1 for YH and OH groups for all trials for all conditions. All boxplots constructed in the same manner as in Fig. 4. Results of corresponding statistical comparisons are provided in Table 4.

Table 4 –

Statistical results for differences between Age groups (YH vs. OH) and Conditions (NOP, VIS and PLAT) for the data shown in Fig. 4, including: control slopes, and correlation (R2) for step width (w) and lateral position (zB). ANOVA results (F-statistics and p-values) are provided for main effects of Age, Condition, and Age×Condition interaction effects, along with the relevant Tukey’s post-hoc comparisons. Significant differences are indicated in bold.

| Data In | Variable | Age | Condition | Age×Condition | Tukey’s (Age Effects) | Tukey’s (Condition Effects) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fig. 4B | slope (w) | F(1,32) = 0.01 p = 0.915 |

F(2,166) = 88.42 p < 0.001 |

F(2,166) = 2.48 p = 0.087 |

N/A | VIS-NOP: p < 0.001 |

| PLAT-NOP: p = 0.587 | ||||||

| slope (zB) | F(1,32) = 0.00 p = 0.976 |

F(2,166) = 140.92 p < 0.001 |

F(2,166) = 0.31 p = 0.735 |

N/A | VIS-NOP: p < 0.001 | |

| PLAT-NOP: p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Fig. 4C | R2 (w) | F(1,32) = 0.01 p = 0.923 |

F(2,166) = 88.50 p < 0.001 |

F(2,166) = 2.40 p = 0.094 |

N/A | VIS-NOP: p < 0.001 |

| PLAT-NOP: p = 0.611 | ||||||

| R2 (zB) | F(1,32) = 0.00 p = 0.970 |

F(2,166) = 134.58 p < 0.001 |

F(2,166) = 0.34 p = 0.714 |

N/A | VIS-NOP: p < 0.001 | |

| PLAT-NOP: p < 0.001 | ||||||

In our simulations (Fig. 6), which reveal underlying sources of stepping changes, increasing additive noise amplitudes alone (i.e., imitating the VIS & PLAT pseudorandom inputs) yielded proportional increases in stepping variability (σ) (Fig. 6A), similar to experiment (Fig. 4B), but elicited no changes in any step-to-step control measures (Fig. 6A and Supplement; Fig. S1). This was not consistent with experiment (Figs 4C & 5). Varying the control proportion (Fig. 6B and Supplement; Fig. S2) also failed to replicate experimental observation (Figs. 4C & 5). Increasing overall control gains (Fig. 6C and Supplement; Fig. S3) did elicit approximately parallel changes in the step-to-step control related measures, consistent with experimental observations (Figs. 4C & 5), but predicted only minimal increases in stepping variability, except at unrealistically high gains (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6 –

Model Simulation Results. Shown here are within-trial standard deviations (σ) and DFA exponents (α), corresponding to Fig. 4B–C. In all subplots, horizontal gray bands indicate experimental mean ± SD for each corresponding measure pooled across all participants in both groups (YH and OH). Red triangles indicate results for “baseline” parameter values (note: all of these fall within the gray bands for all dependent measures). A) Increasing only additive noise induced increased stepping variability (σ). However, there were no changes in any of the step-to-step control related measures. B) Varying the proportionality of control between w and zB to either lower values (i.e., greater zΒ-control and less w-control) or higher values (i.e., greater w-control and less zΒ-control) elicited opposing changes in each of the step-to-step control related variables for w vs. zΒ time series. Such changes were not observed in experiment. C) Increasing the overall control gains for both w and zB simultaneously elicited changes in each of the step-to-step control related variables for w vs. zΒ time series that were qualitatively consistent with experimental findings (Fig. 4C and Fig. 5). See Supplement for additional details and supporting results.

DISCUSSION

At each step, humans must adjust foot placements to maintain walking (Matthis et al., 2017; Zaytsev et al., 2018). Older adults exhibit increased gait variability (Brach et al., 2001; Kang and Dingwell, 2008b) that reflects fall risk (Brach et al., 2007; Verghese et al., 2009). Destabilizing environments also increase gait variability (Francis et al., 2015; McAndrew et al., 2010). Because multiple intrinsic and extrinsic factors contribute to gait variability (Christou, 2011; Twardzik et al., 2019), we must disentangle how age and destabilizing perturbations alter step-to-step regulation, independent of stepping variability. Here, we applied a GEM framework for lateral stepping (Dingwell and Cusumano, 2019) to disambiguate these effects.

The OH and YH groups were very healthy, as they demonstrated similar baseline physical and cognitive capabilities (Table 2). OH adults exhibited slower preferred overground walking speeds and Four Square Step Test times than YH adults (Table 2), but these were both still well within their respective healthy ranges (Dite and Temple, 2002; Studenski et al., 2011). In prior studies, similar healthy older adult cohorts exhibited increased gait variability (Francis et al., 2015; Kang and Dingwell, 2008b) and took wider steps, despite increased energy cost (Dean et al., 2007). While such findings might ‘suggest’ altered control, none of these prior studies quantified measures directly associated with step-to-step regulation.

While both the VIS and PLAT perturbations substantially destabilized all participants, we found negligible differences between how these OH and YH adults responded (Figs. 4–5). OH adults demonstrated similar changes in lateral stepping variability (Fig. 4B), stepping regulation (Fig. 4C), and step-to-step error correction (Fig. 5) compared to YH adults. Thus, OH participants exhibited no noteworthy age-related differences in lateral stepping regulation, even when substantially mechanically perturbed. These findings further confirm and extend our prior work on sagittal plane stepping regulation in OH adults (Dingwell et al., 2017). They also extend findings that healthy older and younger adults walking on an irregular surface also exhibited no significant differences in how the variability of their foot trajectories was structured (Eckardt and Rosenblatt, 2018). Thus, that the OH adults tested here still regulated lateral stepping similar to YH adults demonstrates that age alone does not degrade lateral stepping control. This helps explain why directly connecting gait variability to fall risk has proven difficult (Paterson et al., 2011).

Furthermore, prior work suggested healthy older adults rely more heavily on visual feedback when similar visual perturbations were applied, because those participants exhibited greater increases in variability (Francis et al., 2015) and decreases in step width DFA exponents (Franz et al., 2015) compared to matched controls. However, a subsequent study from the same group (Thompson et al., 2018) did not replicate those differences. The OH adults tested here exhibited only slightly more variable step widths than young adults for the VIS condition (Fig. 4B) and no differences for any stepping control measures (Figs. 4C and 5). Thus, we found no evidence here that age alone induces greater reliance on visual feedback to execute lateral foot placement.

Results confirmed our hypothesis that when walking in destabilizing environments, healthy adults tighten their stepping regulation by increasing step-to-step corrections of lateral position and step width. Within each condition, both DFA (Fig. 4C) and direct control slope (Fig. 5A) results indicate that participants regulated step width more tightly than lateral body position. This tighter control of step width was either maintained or increased further during both VIS and PLAT perturbations (Figs. 4–5). Multi-objective control simulations (Fig. 6 and Supplement) further indicate that while the applied perturbations themselves likely drove increased gait variability regardless of participants’ control strategies (Fig. 6A), participants likely also increased their control gains to enact greater corrections for deviations in both w and zB (Fig. 6C). Importantly, these additional insights cannot be inferred without such computational predictions (Dingwell and Cusumano, 2019).

Prioritizing step width is supported by work showing humans primarily use foot placement to maintain lateral balance (Bruijn and van Dieën, 2018; Hof et al., 2007; Oddsson et al., 2004). Intuitively, this makes sense: you need to maintain balance (via w) regardless of where you are on any path (zB). However, most biomechanical analyses disregard where people step on their path, or dismiss such considerations as “less important than not falling” (Wang and Srinivasan, 2014). The more novel finding here is the concurrent increased/tighter regulation of lateral position (zB). Participants did not simply “trade-off” increased w-control for decreased zB-control (Fig. 6B), but generally increased both w-control and zB-control (Fig. 6C and Supplement; Fig. S3) in a context-dependent way (Dingwell and Cusumano, 2019). For example, direct control results indicate VIS perturbations may increase prioritization to correct w in exchange for only very slightly reduced zB-control, while PLAT perturbations increased prioritization to correct zB without compromising w-control (Fig. 5). Thus, while people indeed strive to maintain lateral balance, they do so while also actively striving to stay on their path (Macdonald, 2009). Indeed, real-world environments always both allow and limit where and how people can walk (Moussaïd et al., 2011) and people modify their stepping behaviors accordingly (Twardzik et al., 2019). That participants here corrected deviations in both step width and position more tightly when perturbed (Figs. 4–6) strongly indicates that staying on one’s path is also a very important goal when choosing foot placements (Matthis et al., 2017).

An intrinsic limitation of this study involves making direct comparisons between VIS and PLAT perturbations. The PLAT perturbations imposed actual physical forces, to which participants had to respond. Conversely, the VIS perturbations were entirely perceptual: modifications in foot placement were due entirely to the perception corrections were needed. Further, for both VIS and PLAT perturbations to illicit comparable responses, the gains (scaling factor A in Eq. 1) of each were quite different (Sinitksi et al., 2012). Thus, while it is difficult to compare stepping responses elicited by the VIS and PLAT conditions directly, our results do demonstrate that people alter their stepping regulation in mostly similar ways when subjected to either type of perturbation.

Gait variability remains generally associated with falls (Toebes et al., 2012; Verghese et al., 2009), but specific connections remain lacking and/or disputed (Brach et al., 2005; Moe-Nilssen and Helbostad, 2005; Paterson et al., 2011). Stepping variability may arise from physiological noise (Christou, 2011), intrinsic redundancy (Todorov, 2004), and/or purposeful adjustments of foot placements (Bruijn and van Dieën, 2018). How much each of these (noise vs. redundancy vs. control) contributes to gait variability must be determined before we can meaningfully relate any such variability to fall risk. The present work is the first to use our recently-developed framework (Dingwell and Cusumano, 2019) to identify how both stepping variability and step-to-step regulation are affected by both age and destabilizing perturbations. While the perturbations applied here did not induce falls, they did directly increase risk of falling (McAndrew et al., 2010; Roos and Dingwell, 2010). Although the perturbations themselves induced significant increases in variability (Fig. 6A), people also responded to both types of perturbations (VIS and PLAT) by more tightly regulating both step width and position (Fig. 6C), despite the intrinsic differences in these perturbation types. Most importantly, our findings demonstrate that healthy aging alone need not necessarily impair these processes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant 1-R01-AG049735.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

We the authors declare that we have no conflicts of interest associated with this work.

REFERENCES

- Bardy BG, Warren WH, Kay BA, 1996. Motion Parallax is Used to Control Postural Sway During Walking. Exp. Brain Res. 111, 271–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen G, Stevens MR, Burns ER, 2016. Falls and Fall Injuries Among Adults Aged ≥65 Years — United States, 2014. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 65, 993–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurskens R, Wilken JM, Dingwell JB, 2014. Dynamic Stability of Individuals with Transtibial Amputation Walking in Destabilizing Environments. J. Biomech 47, 1675–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack-McLagan NK, Cusumano JP, Dingwell JB, 2016. Adaptability of Stride-To-Stride Control of Stepping Movements in Human Walking. J. Biomech 49, 229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brach JS, Berlin JE, VanSwearingen JM, Newman AB, Studenski SA, 2005. Too much or too little step width variability is associated with a fall history in older persons who walk at or near normal gait speed. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil 2, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brach JS, Berthold R, Craik R, VanSwearingen JM, Newman AB, 2001. Gait variability in community-dwelling older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 49, 1646–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brach JS, Studenski SA, Perera S, VanSwearingen JM, Newman AB, 2007. Gait Variability and the Risk of Incident Mobility Disability in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci 62, 983–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijn SM, van Dieën JH, 2018. Control of human gait stability through foot placement. J. R. Soc. Interface 15, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christou EA, 2011. Aging and Variability of Voluntary Contractions. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews 39, 77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean JC, Alexander NB, Kuo AD, 2007. The effect of lateral stabilization on walking in young and old adults. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng 54, 1919–1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker LM, Cignetti F, Potter JF, Studenski SA, Stergiou N, 2012. Use of Motor Abundance in Young and Older Adults during Dual-Task Treadmill Walking. PLoS ONE 7, e41306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delbaere K, Smith T, S., Lord SR, 2011. Development and Initial Validation of the Iconographical Falls Efficacy Scale. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 66A, 674–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwell JB, Cusumano JP, 2010. Re-Interpreting Detrended Fluctuation Analyses of Stride-To-Stride Variability in Human Walking. Gait Posture 32, 348–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwell JB, Cusumano JP, 2015. Identifying Stride-To-Stride Control Strategies in Human Treadmill Walking. PLoS ONE 10, e0124879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwell JB, Cusumano JP, 2019. Humans Use Multi-Objective Control to Regulate Lateral Foot Placement When Walking. PLoS Comput. Biol 15, e1006850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwell JB, John J, Cusumano JP, 2010. Do Humans Optimally Exploit Redundancy to Control Step Variability in Walking? PLoS Comput. Biol 6, e1000856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwell JB, Salinas MM, Cusumano JP, 2017. Increased Gait Variability May Not Imply Impaired Stride-To-Stride Control of Walking in Healthy Older Adults. Gait Posture 55, 131–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dite W, Temple VA, 2002. A clinical test of stepping and change of direction to identify multiple falling older adults. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil 83, 1566–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckardt N, Rosenblatt NJ, 2018. Healthy aging does not impair lower extremity motor flexibility while walking across an uneven surface. Hum. Mov. Sci 62, 67–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer BL, Gleason CE, Gangnon RE, Janczewski J, Shea T, Mahoney JE, 2014. Declining Cognition and Falls: Role of Risky Performance of Everyday Mobility Activities. Phys. Ther 94, 355–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR, 1975. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research 12, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis CA, Franz JR, O’Connor SM, Thelen DG, 2015. Gait variability in healthy old adults is more affected by a visual perturbation than by a cognitive or narrow step placement demand. Gait Posture 42, 380–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz JR, Francis CA, Allen MS, O’Connor SM, Thelen DG, 2015. Advanced age brings a greater reliance on visual feedback to maintain balance during walking. Hum. Mov. Sci 40, 381–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof AL, van Bockel RM, Schoppen T, Postema K, 2007. Control of lateral balance in walking: Experimental findings in normal subjects and above-knee amputees. Gait Posture 25, 250–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John J, Dingwell JB, Cusumano JP, 2016. Error Correction and the Structure of Inter-Trial Fluctuations in a Redundant Movement Task. PLoS Comput. Biol 12, e1005118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HG, Dingwell JB, 2008a. The Effects of Walking Speed, Strength and Range of Motion on Gait Stability in Healthy Older Adults. J. Biomech 41, 2899–2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HG, Dingwell JB, 2008b. Separating the Effects of Age and Speed on Gait Variability During Treadmill Walking. Gait Posture 27, 572–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey JL, Procter-Gray E, Hannan MT, Li W, 2012. Heterogeneity of Falls Among Older Adults: Implications for Public Health Prevention. Am. J. Public Health 102, 2149–2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald JHG, 2009. Lateral excitation of bridges by balancing pedestrians. Proc. Royal Soc. A Math. Phys. Engin. Sci 465, 1055–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Matthis JS, Barton SL, Fajen BR, 2017. The critical phase for visual control of human walking over complex terrain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, E6720–E6729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew PM, Dingwell JB, Wilken JM, 2010. Walking variability during continuous pseudo-random oscillations of the support surface and visual field. J. Biomech 43, 1470–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew PM, Wilken JM, Dingwell JB, 2011. Dynamic Stability of Human Walking in Visually and Mechanically Destabilizing Environments. J. Biomech 44, 644–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moe-Nilssen R, Helbostad JL, 2005. Interstride trunk acceleration variability but not step width variability can differentiate between fit and frail older adults. Gait Posture 21, 164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussaïd M, Helbing D, Theraulaz G, 2011. How simple rules determine pedestrian behavior and crowd disasters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 6884–6888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor SM, Kuo AD, 2009. Direction-Dependent Control of Balance During Walking and Standing. J. Neurophysiol 102, 1411–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddsson LIE, Conrad Wall I, McPartland MD, Krebs DE, Tucker CA, 2004. Recovery from perturbations during paced walking. Gait Posture 19, 24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owings TM, Grabiner MD, 2004. Step width variability, but not step length variability or step time variability, discriminates gait of healthy young and older adults during treadmill locomotion. J. Biomech 37, 935–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson K, Hill K, Lythgo N, 2011. Stride dynamics, gait variability and prospective falls risk in active community dwelling older women. Gait Posture 33, 251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsiadlo D, Richardson S, 1991. The Timed Up and Go Test - A Test of Basic Functional Mobility for Frail Elderly Persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 39, 142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinovitch SN, Feldman F, Yang Y, Schonnop R, Leung PM, Sarraf T, Sims-Gould J, Loughin M, 2013. Video capture of the circumstances of falls in elderly people residing in long-term care: an observational study. Lancet 381, 47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roerdink M, Daffertshofer A, Marmelat V, Beek PJ, 2015. How to Sync to the Beat of a Persistent Fractal Metronome without Falling Off the Treadmill? PLoS ONE 10, e0134148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roerdink M, de Jonge CP, Smid LM, Daffertshofer A, 2019. Tightening Up the Control of Treadmill Walking: Effects of Maneuverability Range and Acoustic Pacing on Stride-to-Stride Fluctuations. Frontiers in Physiology 10, 257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos PE, Dingwell JB, 2010. Influence of Simulated Neuromuscular Noise on Movement Variability and Fall Risk in a 3D Dynamic Walking Model. J. Biomech 43, 2929–2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas MM, Wilken JM, Dingwell JB, 2017. How Humans Use Visual Optic Flow to Regulate Stepping During Walking. Gait Posture 57, 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinitksi EH, Terry K, Wilken JM, Dingwell JB, 2012. Effects of perturbation magnitude on dynamic stability when walking in destabilizing environments. J. Biomech 45, 2084–2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, Rosano C, Faulkner K, Inzitari M, Brach J, Chandler J, Cawthon P, Connor EB, Nevitt M, Visser M, Kritchevsky S, Badinelli S, Harris T, Newman AB, Cauley J, Ferrucci L, Guralnik J, 2011. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA 305, 50–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su JL, Dingwell JB, 2007. Dynamic Stability of Passive Dynamic Walking on an Irregular Surface. J. Biomech. Eng 129, 802–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor ME, Delbaere K, Mikolaizak AS, Lord SR, Close JCT, 2013. Gait parameter risk factors for falls under simple and dual task conditions in cognitively impaired older people. Gait Posture 37, 126–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrier P, Dériaz O, 2012. Persistent and anti-persistent pattern in stride-to-stride variability of treadmill walking: Influence of rhythmic auditory cueing. Hum. Mov. Sci 31, 1585–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Plummer P, Franz JR, 2018. Age and falls history effects on antagonist leg muscle coactivation during walking with balance perturbations. Clin. Biomech 59, 94–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorov E, 2004. Optimality principles in sensorimotor control. Nat. Neurosci 7, 907–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toebes MJP, Hoozemans MJM, Furrer R, Dekker J, van Dieën JH, 2012. Local dynamic stability and variability of gait are associated with fall history in elderly subjects. Gait Posture 36, 527–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twardzik E, Duchowny K, Gallagher A, Alexander N, Strasburg D, Colabianchi N, Clarke P, 2019. What features of the built environment matter most for mobility? Using wearable sensors to capture real-time outdoor environment demand on gait performance. Gait Posture 68, 437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese J, Holtzer R, Lipton RB, Wang C, 2009. Quantitative Gait Markers and Incident Fall Risk in Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 64A, 896–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Srinivasan M, 2014. Stepping in the direction of the fall: the next foot placement can be predicted from current upper body state in steady-state walking. Biol. Lett 10, 20140405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren WH, Kay BA, Yilmaz EH, 1996. Visual Control of Posture During Walking: Functional Specificity. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percep. Perf 22, 818–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaytsev P, Wolfslag W, Ruina A, 2018. The Boundaries of Walking Stability: Viability and Controllability of Simple Models. IEEE Trans Robot. 34, 336–352. [Google Scholar]

- Zeni JA, Richards JG, Higginson JS, 2008. Two simple methods for determining gait events during treadmill and overground walking using kinematic data. Gait Posture 27, 710–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.