Abstract

The 12-kDa FK506-binding protein (FKBP12) is the target of the commonly used immunosuppressive drug FK506. The FKBP12-FK506 complex binds to calcineurin and inhibits its activity, leading to immunosuppression and preventing organ transplant rejection. Our recent characterization of crystal structures of FKBP12 proteins in pathogenic fungi revealed the involvement of the 80’s loop residue (Pro90) in the active site pocket in self-substrate interaction providing novel evidence on FKBP12 dimerization in vivo. The 40’s loop residues have also been shown to be involved in reversible dimerization of FKBP12 in the mammalian and yeast systems. To understand how FKBP12 dimerization affects FK506 binding and influences calcineurin function, we generated Aspergillus fumigatus FKBP12 mutations in the 40’s and 50’s loop (F37M/L; W60V). Interestingly, the mutants exhibited variable FK506 susceptibility in vivo indicating differing dimer strengths. In comparison to the 80’s loop P90G and V91C mutants, the F37M/L and W60V mutants exhibited greater FK506 resistance, with the F37M mutation showing complete loss in calcineurin binding in vivo. Molecular dynamics and pulling simulations for each dimeric FKBP12 protein revealed a two-fold increase in dimer strength and significantly higher number of contacts for the F37M, F37L, and W60V mutations, further confirming their varying degree of impact on FK506 binding and calcineurin inhibition in vivo.

Keywords: Aspergillus, FK506, FKBP12, Calcineurin, Dimerization, Molecular Dynamics

1. Introduction

The immunophilin FKBP12 (12-kDa FK506 binding protein), belongs to the family of peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerases and is an abundant cytosolic protein [1]. It is the target of the clinically-important immunosuppressive drug, FK506, that is the foundation for modern organ transplantation [2]. FK506 binding to FKBP12 is key to inhibition of calcineurin (CN) activity, which involves the formation of the CN-FK506-FKBP12 complex [3, 4]. CN is a heterodimer with catalytic (CnA) and the regulatory (CnB) subunits and is highly conserved across eukaryotes [5]. The FKBP12-FK506 complex binds to a hydrophobic groove in an extended α-helical region of CnA (CnB-Binding Helix) and the associated CnB subunit to inhibit CN activity [6]. Due CN inhibition, the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) is not dephosphorylated by CN and therefore, unable to translocate from the cytoplasm to the nucleus to induce the transcription of interleukin-2 leading to immune suppression [7, 8]. While the role of CN in T lymphocytes activation is established in mammals [9], its importance for fungal growth, stress response and pathogenesis makes it a promising antifungal target [10–12]. Our recent CN-FK506-FKBP12 complexes crystallization studies in major human fungal pathogens revealed overall conservation with the mammalian complexes at the interface between CN and the FKBP12-FK506 complex, but specific differences were noted in the binding surfaces of CN and FKBP12 [13].

The use of FKBP12 in dimerization applications to study cellular functions has emerged as a powerful tool [14], made possible by the serendipitous discovery of dimerization of the mammalian FKBP12 through a single 40’s loop mutation at Phe37 residue [15–17]. Other 40’s and 50’s loop residues have been shown to be involved in reversible dimerization of FKBP12 in the mammalian and yeast systems [14, 17]. We crystallized the A. fumigatus FKBP12 (AfFKBP12) in its apo form (PDB 5HWB) and captured its dimerization, with one FKBP12 80’s loop Pro90 residue in a cis conformation bound to the second FKBP12 monomer with the Pro90 residue in a trans conformation indicative of possible self-catalysis function [18]. Efforts to crystallize the wild-type AfFKBP12 bound to FK506 failed, but we were able to crystallize the complex by mutation of the Pro90 residue to Gly90 (P90G) in AfFKBP12 (PDB 5HWC) [18]. Comparison of the apo AfFKBP12 structure with AfFKBP12 (P90G)-FK506 complex revealed that the self-substrate binding region overlaps the FK506-binding site. In addition, based on the AfFKBP12 (P90G)-FK506 structure we introduced a Cys mutation at the Val91 residue (V91C) to capture the FKBP12 intermolecular interaction and confirmed that AfFKBP12 (V91C) dimerization occurs in solution [18]. Physiological assessment of these mutations in vivo revealed that both P90G and V91C mutations conferred FK506 resistance to different degrees, with the V91C mutant showing higher resistance coinciding with decreased CN affinity in vivo [18].

To better understand the role of the 40’s and 80’s loops in FKBP12 intermolecular interactions and how this translates to ligand binding and CN inhibition in vivo, we introduced mutations in the 40’s and 50’s loops of AfFKBP12 to induce dimerization. We reveal for the first time the consequence of different FKBP12 dimerization mutations on FK506 sensitivity and CN inhibition in vivo by utilizing genetic and molecular dynamics coupled with pulling simulations.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Strains, culture conditions and construction of FKBP12 mutants

A. fumigatus akuBKU80 (wild-type; WT) was used for growth and transformation experiments [19]. Strains were cultured in the presence or absence of different concentrations of FK506 (0.1–5 μg/ml) on GMM agar (for 3–5 days) or RPMI 1640 liquid media (for 48 h) at 37°C. E. coli DH5α was used for subcloning. Site-directed mutagenesis of FKBP12 (F37M, F37L, W60V) was performed by PCR using the pUCGH-FKBP12cDNA plasmid with Affkbp12 cDNA (fkbp1/Afu6g12170) as template. In the first PCR, two fragments were amplified using complementary primers (with respective mutation) overlapping the fkbp12 region to be mutated and pUCGH-F and pUCGH-R primers flanking the N- and C-terminus of the fkbp12 cDNA. To express the gfp fusion no stop codon was introduced at the C-terminus of fkbp12. Next, fusion PCR using an equi-proportional mixture of the two PCR fragments as templates, the final fkbp12 cDNA mutated fragment (336 bp) was amplified with pUCGH-F and pUCGH-R primers. Mutated fkbp12 fragments were BamHI digested and cloned into the pUCGH-Fkbp12promo-Fkbp12term vector with 800 bp fkbp12 promoter and 1006 bp terminator to replace the 384 bp wild-type fkbp12 gene. Mutated fkbp12s were sequenced, linearized with KpnI, transformed into the akuBKU80 strain and selected with hygromycin B (150 μg/ml). Transformants were PCR verified for homologous integration (Suppl. Figs. 1–4) and for sequence accuracy (Suppl. Figs. 5–7). All primers and strains are listed (Suppl. Table 1 and Suppl. Table 2).

2.2. Fluorescence microscopy

Conidia of A. fumigatus recombinant strains expressing mutated forms of FKBP12-GFP fusion proteins (F37M, F37L, and W60V) were inoculated in 5 ml GMM medium in the absence or presence of FK506 (100 ng/ml) on coverslips in a 60 × 15 mm petri dish, cultured for 18–20 h at 37ºC. Fluorescence microscopy was performed using a Zeiss Axioskop 2 plus microscope equipped with AxioVision 4.6 imaging software.

2.3. Molecular dynamics and dimer pulling simulations

Molecular dynamic (MD) simulations were performed for 100 ns using the GROMACS 5.0.1 software, GROMOS53a6 force field, and the flexible simple point-charge water model [20]. The starting conformations used for the MD simulations were either PDB 5HWB (WT, P90G, F37L, F37M, and W60V) or PDB 5J6E (V91C) [18]. The initial structures were immersed in a periodic water box (dodecahedron - 1 nm edges) and neutralized with counter ions. Energy minimization used the steepest descent algorithm with a final maximum force below 100 kJ/mol/min (0.01 nm step size, cutoff of 1.4 nm for neighbor list, Coulomb interactions, and Van der Waals interactions). Next, the system was equilibrated at 300 K and normal pressure for 1 ns. All bonds were constrained with the LINCS algorithm (same cutoffs). After temperature stabilization, pressure stabilization was obtained by utilizing the v-rescale thermostat to hold the temperature at 300 K and the Berendsen barostat was used to bring the system to 1 bar pressure. Production MD calculations (100 ns) were performed under the same conditions except that the position restraints were removed (same cutoffs). Ending structures of these trajectories were used as starting configurations for pulling simulations. The pulling simulations utilized identical solvating conditions as stated above except that the AfFKBP12 structures were placed in a rectangular box with sufficient space for pulling. Equilibration was performed for 100 ps under an NPT ensemble, using the same methodology described above. Following equilibration, all restraints were removed from chain B in the AfFKBP12 system while those for chain A were retained; to ensure it was used as an immobile reference for the pulling simulations. For each dimer, chain B was pulled away from the core structure along the z-axis over 500 ps (spring constant of 1000 kJ mol−1 nm−2 and a pull rate of 0.01 nm ps−1). A final center-of-mass (COM) distance between chain A and B of approximately 9.5 nm was achieved. Starting configurations for the umbrella sampling windows (a sampling distribution with a lower energy barrier to sample the unfavorable conformational states between two stable conformations, e.g., the transition from a dimeric to monomeric conformation) were taken from these trajectories. An asymmetric distribution of sampling windows was used such that the window spacing was 0.25–0.3 nm up to 9.5 nm COM separation (Suppl. Fig. 8). In each window, 10 ns of MD was performed for a total simulation time of 500 ns with an average of 30 simulations used between ~3 nm to 9.5 nm utilized for umbrella sampling. GROMACS built-in and homemade scripts were used to analyze the MD simulation results [21]. Statistical errors of the free energy profiles were estimated using bootstrap analysis [22, 23]and the zero set point was 10nm. All scoring of protein-protein complexes were accomplished through FireDock [24]. Each resulting potential of mean force (PMF) and FireDock curve was fitted to: y=A0*exp(A1*x), while the number of contact curves were fit to : y=A0*exp(−A1*x) using Grace (http://plasma-gate.weizmann.ac.il/Grace/). All images were produced with PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.7.4 Schrödinger, LLC.).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. A. fumigatus FKBP12 dimer mutants are altered in FK506 susceptibility

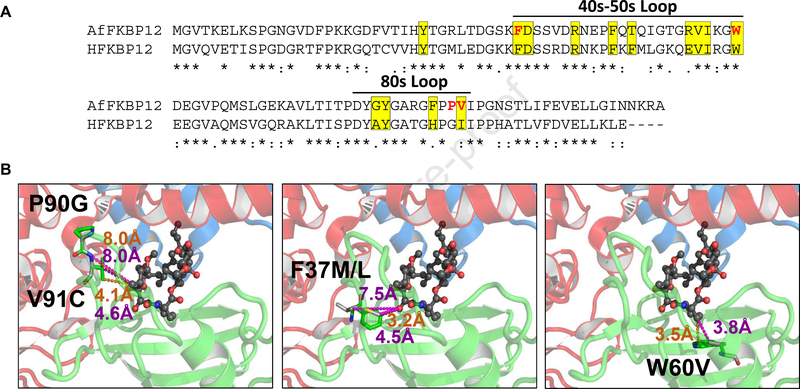

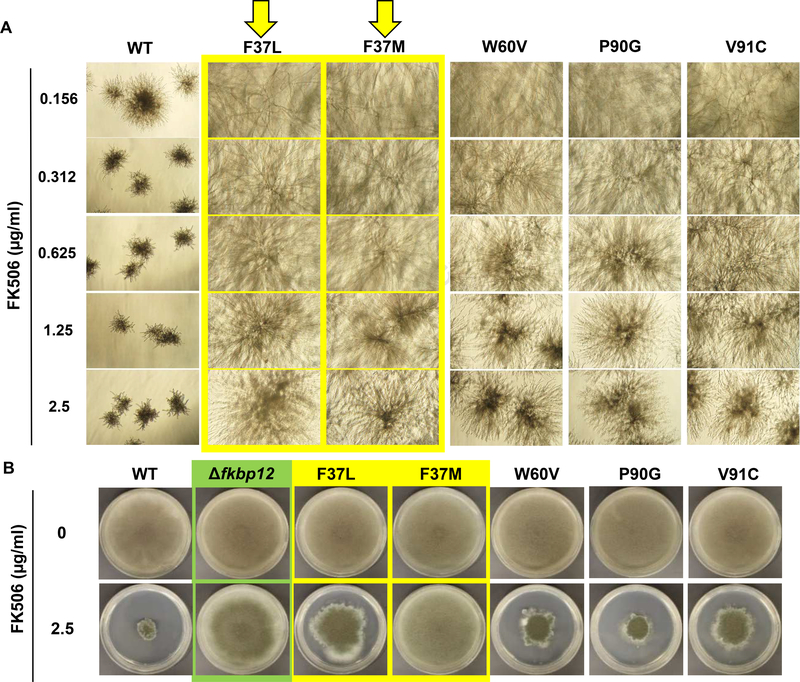

FKBP12 contains two main loops, the 40’s-50’s and the 80’s loops (Fig. 1A), wherein majority interactions with FK506 and the CN complex occur. Of the fourteen FKBP12 residues that reside within 5Å of FK506, thirteen residues are present in these two main loops. While nine of these residues are conserved between the human and A. fumigatus counterparts, two residues each in the 40’s-50’s loop (T49 and R55) and in the 80’s loop (G82 and V91) are not conserved. Importantly, the AfFKBP12 Pro90 residue that is a Gly90 in human FKBP12 (HFKBP12) and resides more than 5Å away from FK506 (Fig. 1B; panel 1) appears to be important for inducing FK506 sensitivity in a fungal-specific manner because mutation of Pro90 to Gly90 (P90G) induced FK506 resistance. Therefore, based on our previous observation of increased FK506 resistance in the AfFKBP12 80’s loop mutants (P90G and V91C) and the dimerization of the V91C mutant, we wanted to verify the contribution of the 40’s-50’s loop in FKBP12 dimerization and make quantitative comparisons on FK506 binding and CN inhibition in vivo between the mutants. For this, we chose to mutate two residues, Phe37 and Trp60, which are 3.2Å and 3.8Å away respectively from FK506 in the crystal structure (PDB 5HWC), and were previously shown to promote dimerization in mammalian FKBP12 [15, 16] (Fig. 1B; panels 2 and 3). Two Phe37 site mutants, F37M and F37L, and a single Trp60 site mutant, W60V, were generated and phenotyped for FK506 susceptibility in both liquid and agar cultures (Fig. 2). At all the concentrations tested, the wild-type strain was completely FK506 sensitive, indicating FK506 complexing with AfFKBP12 and inhibiting CN (Fig. 2A). Testing the mutated strains in the presence of increasing concentrations of FK506 (in RPMI liquid) revealed that the F37M and F37L strains were more resistant in comparison to the W60V, P90G, and V91C strains, indicating alterations in FK506 binding due to these mutations. However at 2.5 μg/ml FK506 (on GMM agar), in comparison to the F37L strain the F37M strain was as resistant as the Affkbp12 deletion strain (Δfkbp12), but the W60V, P90G, and V91C strains showed greater FK506 susceptibility (Fig. 2B). Together these results suggest that the variable FK506 susceptibility of the AfFKBP12 mutants might be dependent on the protein-protein contact residues during dimer formation, the strength of the contacts, and the ability of the dimer to dissociate in the presence of the ligand.

FIG. 1.

(A) Alignment of A. fumigatus and human FKBP12s showing the loops. Residues within 5Å of FK506 are highlighted yellow. Residues important for FKBP12 dimerization are colored red. (B) Cartoon representation of the A. fumigatus CN-FK506-FKBP12 complex (PDB 6TZ7): CnA (red), CnB (blue), FKBP12 (green) and FK506 (black stick and sphere format). Mutations P90G, V91C, F37M/L and W60V (pymol generated using PDB 6TZ7 as template) are in grey with their respective distance to FK506. Residue atoms closest to FK506 in the wild-type protein (orange) and the closest residue atom to FK506 due to the mutation (purple) are shown.

FIG. 2.

(A) The wild-typeakuBKU80 (WT), the ΔAffkbp12, and the Affkbp12 mutant strains (F37L, F37M, W60V, P90G, and V91C; 104 spores/ml) were cultured in RPMI liquid media for 48 h with FK506 (0.156–2.5 μg/ml) and observed by inverted microscope. (B) Growth of the WT and the various Affkbp12 mutant strains was assessed after 5-days on GMM agar with or without FK506 (2.5 μg/ml).

3.2. Dimer pulling simulations show stronger FKBP12 dimer interface with 40’s-50’s loop mutations

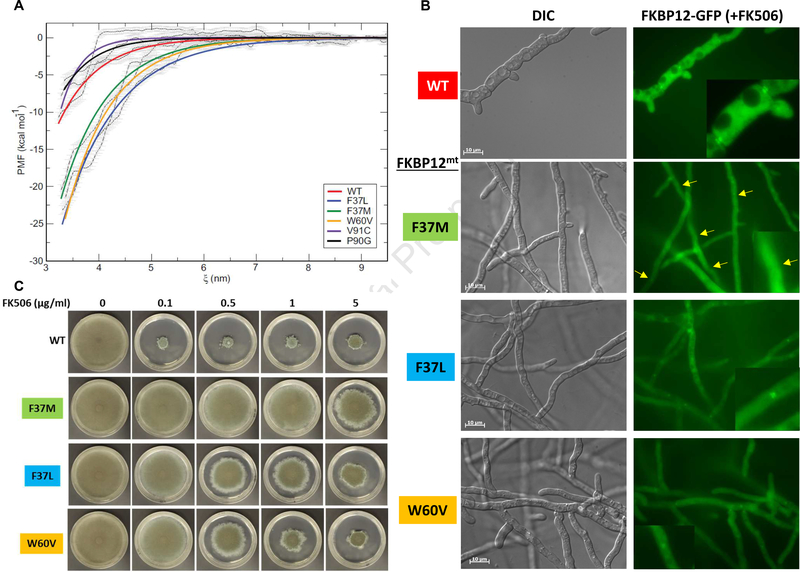

To investigate the differences in FK506 susceptibility of the different AfFKBP12 mutants, MD simulations for the wild-type and each of the dimeric FKBP12 mutants were performed. First, 100 ns simulations were performed to relax the X-ray crystal contacts and accommodate any necessary structural alterations due to the respective mutations. Next, the ending structure from each 100 ns MD simulation was utilized as the starting structure for the dimer pulling simulations (Fig. 3A). In these simulations, one chain of the dimeric AfFKBP12 was pulled away from the other along the z-axis and the PMF was measured to approximate the ΔG of binding for one monomer to another (e.g., the strength of the dimer interface). Approximately 30 sample windows for each protein along the z-axis were collected (Suppl. Fig. 8) for each dimeric AfFKBP12 and a weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) was performed and error analysis was calculated by the bootstrapping method [21, 23]. Accounting for standard error (±2 kcal/mol) in the PMF, AfFKBP12:V91C (−9.5 kcal/mol) and AfFKBP12:WT (−11.3 kcal/mol) are virtually indistinguishable from one another in the ΔG of binding between monomer A and B. The AfFKBP12:P90G (−6.9 kcal/mol) mutation is slightly more distinguishable from AfFKBP12:WT with a less stable dimerization interface, a ΔΔG of 4.4 kcal/mol. Finally, AfFKBP12:F37L, AfFKBP12:F37M, and AfFKBP12:W60V (−25.1, −21.5, and −24.4 kcal/mol) appear to have twice the strength of the ΔG of binding between monomer A and B compared to AfFKBP12:WT (−11.3 kcal/mol) (Fig. 3A and Suppl. Table 3). The resulting hierarchy in ΔG of binding (PMF) between monomer A and B of AfFKBP12 suggests that AfFKBP12:P90G <AfFKBP12:V91C= AfFKBP12:WT<<AfFKBP12:F37L = AfFKBP12:F37M = AfFKBP12:W60V.

FIG. 3. (.

A) Potential of mean force (PMF) curves and WHAM (weighted histogram analysis method) generated curves are shown in black lines with grey error bars. WT (red), F37L (blue), F37M (green), W60V (orange), V91C (indigo), and P90G (black). (B) Fluorescence microscopy of A. fumigatus wild-type (WT) and the Affkbp12 mutants tagged to GFP in the presence of FK506 (100 ng/ml). White arrows show septal localization of the WT and AfFKBP12-F37L and W60V proteins indicating their binding to calcineurin at the hyphal septum. Yellow arrows show the absence of septal localization of AfFKBP12-F37M mutant protein. (C) Growth of the WT and the strains expressing Affkbp12 mutants after 5-days on GMM agar with FK506 (0–5 μg/ml). Note the concentration dependent increase in FK506 sensitivity of the F37L and W60Vmutants indicative of FK506 ligand concentration induced FKBP12 dimer dissociation and CN inhibition.

3.3. AfFKBP12-F37M dimer mutation impairs calcineurin binding

We previously demonstrated that A. fumigatus CN complex localizes to the hyphal septum and that AfFKBP12 binds to CN at the septum in the presence of FK506 and inhibits its activity [25]. To investigate if the increased FK506 resistance in the 40’s-50’s loop mutants is due to the inability of the FKBP12-FK506 complex to bind CN in vivo, we visualized the localization pattern of the AfFKBP12 proteins tagged to GFP in the presence of FK506 (0.1 μg/ml). While each of the AfFKBP12 proteins (including the wild-type) showed cytosolic and nuclear localization in the absence of FK506 (data not shown) as we previously reported [18, 26], FK506 treatment showed translocation of AfFKBP12 to the septum indicating its binding to CN at the septum (Fig. 3B; top panel). However, the AfFKBP12-F37M mutant did not show septal localization upon FK506 treatment (Fig. 3B; F37M panel), supporting the observed complete FK506 resistance at 0.1 μg/ml (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, although the F37L and the W60V mutants also showed complete FK506 resistance at 0.1 μg/ml, they still showed septal localization in response to the presence of FK506 (Fig. 3B; F37L and W60V panels). Moreover, the F37L and W60V mutants showed FK506 concentration-dependent increased susceptibility wherein the W60V mutant was as sensitive as the wild-type strain in the presence of 5 μg/ml FK506. This indicated the ability of the F37L/W60V dimer dissociation in the presence of the FK506 ligand. The dissociation of the dimer probably facilitates the enhanced binding of FK506 to FKBP12 and resulting in FK506 sensitivity. Recent work on reversible dimerization mutants in mammalian FKBP12 has shown the ligand induced dissociation of the dimer enabling ligand binding and occlusion of the dimerization interface [14].

3.4. Structural details of AfFKBP12 dimer mutant proteins reveal important contact residue differences between the 80’s loop versus the 40’s-50’s loop residues

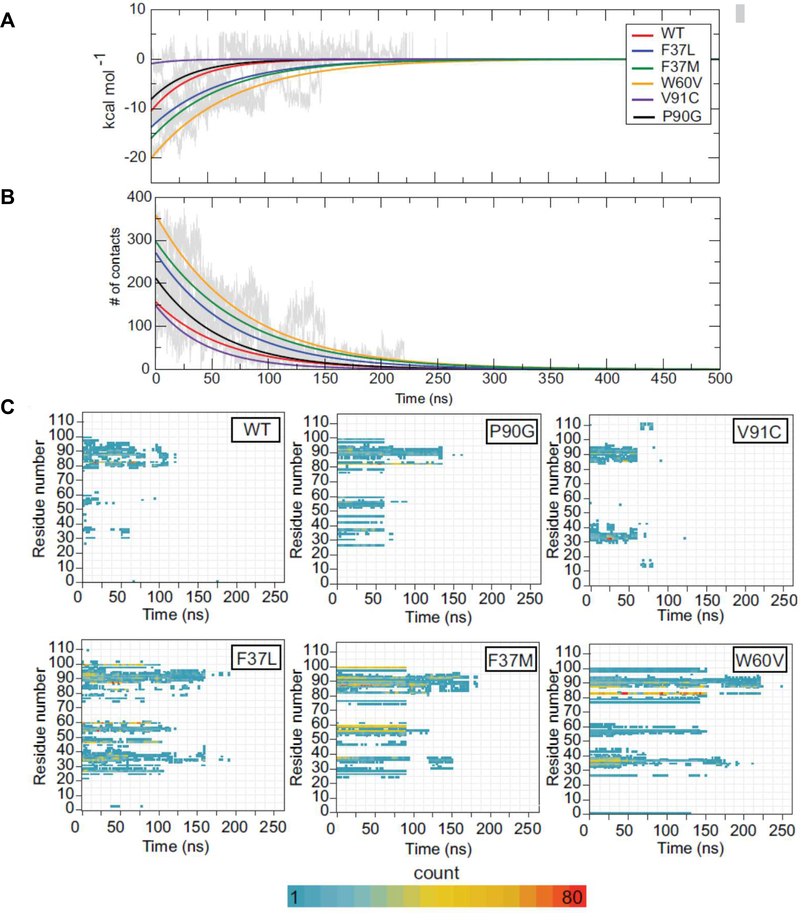

The number of residue contacts between the AfFKBP12 dimer mutants may dictate the strength of the dimer interface and the ability of the dimer to dissociate in the presence of the ligand. For the analysis of the residue contacts, each dimer pulling simulation was concatenated into 500 ns long MD simulation. FireDock scoring algorithms were used to score each protein:protein dimer interface during the dimer pulling simulation to account for van der Waals interactions, atomic contact energy, electrostatic, and additional binding free energy estimations between the monomers. The resulting hierarchy in binding energy between monomer A and B of AfFKBP12 suggests the strength of the homodimers results in the following hierarchy: AfFKBP12:V91C <AfFKBP12:P90G <AfFKBP12:WT<AfFKBP12:F37L <AfFKBP12:F37M <AfFKBP12:W60V, which mirrors that of the PMF analysis (Figs. 3A, 4A, and Suppl. Table 3). In addition, determining the number of contacts between each monomer (defined as two atoms, one from each monomer, within 4Å of another) suggest a similar number of contacts for AfFKBP12:WT and AfFKBP12:V91C, with an increased amount for AfFKBP12:P90G, and a significant increased number for AfFKBP12:F37L, AfFKBP12:F37M, and AfFKBP12:W60V (Fig. 4B). A detailed analysis of the number of interactions per residue versus time (Fig. 4C) reveals several aspects that are similar between AfFKBP12:WT, AfFKBP12:P90G, and AfFKBP12:V91C as well as between AfFKBP12:F37L, AfFKBP12:F37M, and AfFKBP12:W60V. Within AfFKBP12:WT, the largest number of interactions between the monomers are as result of residues in and around the 80s’s loop, with additional contacts with the 30’s loop and 50’s loop. In fact, AfFKBP12:P90G and AfFKBP12:V91C showed similar contacts with AfFKBP12:P90G showing longer-lived contacts within the 80’s and 50’s loop. Interestingly, AfFKBP12:V91C interactions while similar in location are relatively short lived compared to AfFKBP12:P90G and AfFKBP12:WT.AfFKBP12:WT, AfFKBP12:P90G, and AfFKBP12:V91C also each end any interactions between monomers around 125–135 ns with the majority of interactions for AfFKBP12:V91C ending around 75 ns. Finally, AfFKBP12:WT and AfFKBP12:P90G lose interactions in the 50’s and 30’s loop within the first 75 ns and those interactions within the 80’s loop last the longest (AfFKBP12:V91C loses interactions in the 30’s and 80’s loop at the same time) (Fig. 4C; top row).

FIG. 4.

(A) Firedock scoring of each dimeric complex throughout the simulation time. (B) Number of contacts between each dimeric complex throughout the simulation time. Panels A and B: WT (red), F37L (blue), F37M (green), W60V (orange), V91C (indigo), and P90G (black). (C) Three-dimensional plots of the number of contacts per residue versus time. Each plot is labeled with the corresponding FKBP12 mutation.

AfFKBP12:F37L, AfFKBP12:F37M, and AfFKBP12:W60V all share similarities between each other and are quite different to those observed in AfFKBP12:WT, AfFKBP12:P90G, and AfFKBP12:V91C. AfFKBP12:F37L and AfFKBP12:F37Mshare common contacts with residues G34, F47, G59, G87, P93, G94, and I99. AfFKBP12:F37M also heavily relies on residue V56, but AfFKBP12:F37L does so to a lesser extent and time. AfFKBP12:W60V heavily relies on residues G34, K36, F37, Y83, and G87 (Fig. 4C; bottom row). AfFKBP12:WT and AfFKBP12:P90G heavily rely on residue Y83, while AfFKBP12:V91C relies on residue D33 and I91. AfFKBP12:WT, AfFKBP12:P90G, and AfFKBP12:V91C relied on contacts in the 30’s for approximately 75 ns while for the AfFKBP12:F37L, AfFKBP12:F37M, and AfFKBP12:W60V mutants these interactions last greater than 150 ns with AfFKBP12:W60V lasting 175 ns. Interactions within the 80’s loop lasted approximately 175 ns for AfFKBP12:F37L and AfFKBP12:F37M while lasting 225 ns for AfFKBP12:W60V. This compared to the 75–125 ns for AfFKBP12:WT, AfFKBP12:P90G, and AfFKBP12:V91C suggest that those interactions within the 30’s and 80’s loop add to the stability of these mutant proteins.

Conclusion

Dimer pulling simulations were used to investigate the structural ramifications of the FKBP12 mutation that lead to variable FK506 susceptibility in vivo. These simulations lead to a hierarchy of strength of dimers between monomer A and B of AfFKBP12; AfFKBP12:P90G < AfFKBP12:V91C = AfFKBP12:WT << AfFKBP12:F37L = AfFKBP12:F37M = AfFKBP12:W60V which closely resembles the FK506 susceptibility in vivo experiments. While all mutations used the 40’s loop to increase dimerization strength compared to WT, F37L/M, and W60V AfFKBP12 mutants’ increased dimerization strength can be structurally attributed to a significant increase in interactions in the 80’s loop despite the mutation location structurally allosteric to the 80’s loop. In fact, mutations within the 80’s loop (P90G and V91C) weaken the strength of homo-dimerization relative to allosteric mutations.

All third-party financial support for the work in the submitted manuscript.

All financial relationships with any entities that could be viewed as relevant to the general area of the submitted manuscript.

All sources of revenue with relevance to the submitted work who made payments to you, or to your institution on your behalf, in the 36 months prior to submission.

Any other interactions with the sponsor of outside of the submitted work should also be reported.

Any relevant patents or copyrights (planned, pending, or issued).

Any other relationships or affiliations that may be perceived by readers to have influenced, or give the appearance of potentially influencing, what you wrote in the submitted work. As a general guideline, it is usually better to disclose a relationship than not.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Aspergillus fumigatus FKBP12 dimerizing mutations alter FK506 susceptibility

Molecular dynamics simulations revealed structural ramifications in AfFKBP12 dimers

Mutations in the 40’s-50’s loop reveal strong AfFKBP12 dimer interface

AfFKBP12-F37M dimer is impaired in calcineurin binding in vivo

AfFKBP12 dimers contact residues differ in the 80’s versus the 40’s-50’s loops

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH/NIAID (R01 AI112595-04; P01 AI104533-03) grants. S.M.G. is a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) postdoctoral fellow. Support from Duke’s Research Computing staff to use the Duke Computing Cluster, and the Duke NMR Center for computing capability is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- FKBP12

FK506-binding protein

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- MD

molecular dynamics

- CN

Calcineurin

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interests

☒ The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Siekierka JJ, Hung SHY, Poe M, Lin CS, Sigal NH, A cytosolic binding protein for the immunosuppressant FK506 has peptidyl-prolyl isomerase activity but is distinct from cyclophilin, Nature, 341 (1989) 755–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Liu J, Farmer JD, Lane WS, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber SL, Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes, Cell, 66 (1991) 807–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kissinger CR, Parge HE, Knighton DR, Lewis CT, Pelletier LA, Tempczyk A, Kalish VJ, Tucker KD, Showalter RE, Moomaw EW, Gastinel LN, Habuka N, Chen X, Maldonado F, Barker JE, Bacquet R, Villafranca JE, Crystal structures of human calcineurin and the human FKBP12–FK506–calcineurin complex, Nature, 378 (1995) 641–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Griffith JP, Kim JL, Kim EE, Sintchak MD, Thomson JA, Fitzgibbon MJ, Fleming MA, Caron PR, Hsiao K, Navia MA, X-ray structure of calcineurin inhibited by the immunophilin-immunosuppressant FKBP12-FK506 complex, Cell, 82 (1995) 507–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hemenway CS, Heitman J, Calcineurin, Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics, 30 (1999) 115–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Li H, Rao A, Hogan PG, Interaction of calcineurin with substrates and targeting proteins, Trends in Cell Biology, 21 (2011) 91–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Luo C, Shaw KT, Raghavan A, Aramburu J, Garcia-Cozar F, Perrino BA, Hogan PG, Rao A, Interaction of calcineurin with a domain of the transcription factor NFAT1 that controls nuclear import, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 93 (1996) 8907–8912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Flanagan WM, Corthésy B, Bram RJ, Crabtree GR, Nuclear association of a T-cell transcription factor blocked by FK-506 and cyclosporin A, Nature, 352 (1991) 803–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Clipstone NA, Crabtree GR, Identification of calcineurin as a key signalling enzyme in T-lymphocyte activation, Nature, 357 (1992) 695–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Park H-S, Lee SC, Cardenas ME, Heitman J, Calcium-Calmodulin-Calcineurin Signaling: A Globally Conserved Virulence Cascade in Eukaryotic Microbial Pathogens, Cell Host & Microbe, 26 (2019) 453–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Juvvadi PR, Lee SC, Heitman J, Steinbach WJ, Calcineurin in fungal virulence and drug resistance: Prospects for harnessing targeted inhibition of calcineurin for an antifungal therapeutic approach, Virulence, 8 (2017) 186–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Steinbach WJ, Reedy JL, Cramer RA, Perfect JR, Heitman J, Harnessing calcineurin as a novel anti-infective agent against invasive fungal infections, Nature Reviews Microbiology, 5 (2007) 418–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Juvvadi PR, Fox D 3rd, Bobay BG, Hoy MJ, Gobeil SMC, Venters RA, Chang Z, Lin JJ, Averette AF, Cole DC, Barrington BC, Wheaton JD, Ciofani M, Trzoss M, Li X, Lee SC, Chen Y-L, Mutz M, Spicer LD, Schumacher MA, Heitman J, Steinbach WJ, Harnessing calcineurin-FK506-FKBP12 crystal structures from invasive fungal pathogens to develop antifungal agents, Nat Commun, 10 (2019) 4275–4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Barrero JJ, Papanikou E, Casler JC, Day KJ, Glick BS, An improved reversibly dimerizing mutant of the FK506-binding protein FKBP, Cellular Logistics, 6 (2016) e1204848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rollins CT, Rivera VM, Woolfson DN, Keenan T, Hatada M, Adams SE, Andrade LJ, Yaeger D, van Schravendijk MR, Holt DA, Gilman M, Clackson T, A ligand-reversible dimerization system for controlling protein–protein interactions, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97 (2000) 7096–7101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Clackson T, Yang W, Rozamus LW, Hatada M, Amara JF, Rollins CT, Stevenson LF, Magari SR, Wood SA, Courage NL, Lu X, Cerasoli F, Gilman M, Holt DA, Redesigning an FKBP–ligand interface to generate chemical dimerizers with novel specificity, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 95 (1998) 10437–10442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Schories B, Nelson TE, Sane DC, Multimer formation by FKBP-12: roles for cysteine 23 and phenylalanine 36, Journal of Peptide Science, 13 (2007) 475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tonthat NK, Juvvadi PR, Zhang H, Lee SC, Venters R, Spicer L, Steinbach WJ, Heitman J, Schumacher MA, Structures of Pathogenic Fungal FKBP12s Reveal Possible Self-Catalysis Function, mBio, 7 (2016) e00492–00416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bok JW, Keller NP, LaeA, a Regulator of Secondary Metabolism in Aspergillus spp, Eukaryotic Cell, 3 (2004) 527–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Abraham MJ, Murtola T, Schulz R, Páll S, Smith JC, Hess B, Lindahl E, GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers, SoftwareX, 1–2 (2015) 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kumar S, Rosenberg JM, Bouzida D, Swendsen RH, Kollman PA, THE weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. I. The method, Journal of Computational Chemistry, 13 (1992) 1011–1021. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hub JS, de Groot BL, Does CO2 Permeate through Aquaporin-1?, Biophysical Journal, 91 (2006) 842–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lemkul JA, Bevan DR, Assessing the Stability of Alzheimer’s Amyloid Protofibrils Using Molecular Dynamics, The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 114 (2010) 1652–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mashiach E, Schneidman-Duhovny D, Andrusier N, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ, FireDock: a web server for fast interaction refinement in molecular docking, Nucleic Acids Research, 36 (2008) W229–W232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Juvvadi PR, Fortwendel JR, Rogg LE, Burns KA, Randell SH, Steinbach WJ, Localization and activity of the calcineurin catalytic and regulatory subunit complex at the septum is essential for hyphal elongation and proper septation in Aspergillus fumigatus, Molecular Microbiology, 82 (2011) 1235–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Falloon K, Juvvadi PR, Richards AD, Vargas-Muñiz JM, Renshaw H, Steinbach WJ, Characterization of the FKBP12-Encoding Genes in Aspergillus fumigatus, PLOS ONE, 10 (2015) e0137869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.