Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Classification of stroke as cardioembolic in etiology can be challenging, particularly since the predominant cause, atrial fibrillation (AF), may not be present at the time of stroke. Efficient tools that discriminate cardioembolic from noncardioembolic strokes may improve care as anticoagulation is frequently indicated after cardioembolism. We sought to assess and quantify the discriminative power of AF risk as a classifier for cardioembolism in a real-world population of patients with acute ischemic stroke.

Methods:

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of a multi-institutional sample of patients with acute ischemic stroke. We systematically adjudicated stroke subtype and examined associations between AF risk using CHA2DS2-VASc, Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology AF (CHARGE-AF), and the recently developed electronic health record-based AF (EHR-AF) scores, and cardioembolic stroke using logistic regression. We compared the ability of AF risk to discriminate cardioembolism by calculating c-statistics and sensitivity/specificity cutoffs for cardioembolic stroke.

Results:

Of 1,431 individuals with ischemic stroke (age 65±15, 40% female), 323 (22.6%) had cardioembolism. AF risk was significantly associated with cardioembolism (odds ratio [OR] per SD of CHA2DS2-VASc 1.69 [95%CI 1.49-1.93]; CHARGE-AF OR 2.22 [95%CI 1.90-2.60]; EHR-AF OR 2.55 [95%CI 2.16-3.04]). Discrimination was greater for CHARGE-AF (c-index 0.695 [95%CI 0.663-0.726]) and EHR-AF (0.713 [95%CI 0.681-0.744]) versus CHA2DS2-VASc (c-index 0.651 [95%CI 0.619-0.683]). Examination of AF scores across a range of thresholds indicated that AF risk may facilitate identification of individuals at low likelihood of cardioembolism (e.g., negative likelihood ratios for EHR-AF ranged 0.31-0.10 at sensitivity thresholds 0.90-0.99).

Conclusions:

AF risk scores associate with cardioembolic stroke and exhibit moderate discrimination. Utilization of AF risk scores at the time of stroke may be most useful for identifying individuals at low probability of cardioembolism. Future analyses are warranted to assess whether stroke subtype classification can be enhanced to improve outcomes in undifferentiated stroke.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, stroke, risk prediction

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the leading cause of cardioembolic stroke, and is associated with substantial morbidity and economic cost.1 Identification of AF as the etiology of stroke is critical, since anticoagulation can prevent recurrent stroke.2 However, AF is frequently unrecognized at the time of stroke,3,4 and is often detected only after long-term monitoring.5 The use of extended monitoring is expensive, utilization remains limited,6 and most patients who receive monitoring do not have AF.3,4 Moreover, indiscriminate anticoagulation for suspected but unconfirmed cardioembolism has not proven effective and increases bleeding.7 Thus, there is a critical need to better identify individuals with cardioembolism who would ultimately benefit from anticoagulation.

Previous studies have demonstrated that AF risk can be estimated using clinical scores.8 Recent work has also shown that the CHA2DS2-VASc9 stroke risk score predicts embolic strokes better than other subtypes,10 indicating that clinical factors other than AF itself may be important proxies for cardioembolism. Given the close association between AF and cardioembolism, we hypothesized that quantification of AF risk may sufficiently classify cardioembolic (versus non-cardioembolic) strokes. If AF risk discriminates cardioembolism, its use may guide management of patients with undifferentiated ischemic strokes. Specifically, more intensive rhythm monitoring may be indicated in patients at sufficiently high likelihood of cardioembolism. Conversely, deferral of invasive rhythm monitoring may be reasonable and cost-effective in patients at low likelihood of having had an AF-related cardioembolic stroke.

Therefore, we sought to compare whether AF risk, as compared to gold-standard stroke subtype labeling, is sufficient to classify cardioembolic versus non-cardioembolic stroke. We applied three validated clinical AF risk schemes: CHA2DS2-VASc9, the Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology AF score (CHARGE-AF)8, and the electronic health record-based AF score (EHR-AF)11, to estimate AF risk in a broad population of ischemic stroke patients. We further modeled the test characteristics of AF risk in a simulated sample of individuals with undifferentiated stroke subtypes (i.e., without diagnosed AF), to assess the potential impact of utilizing AF risk as a cardioembolism classifier.

Methods

Data sharing

Study data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study Population

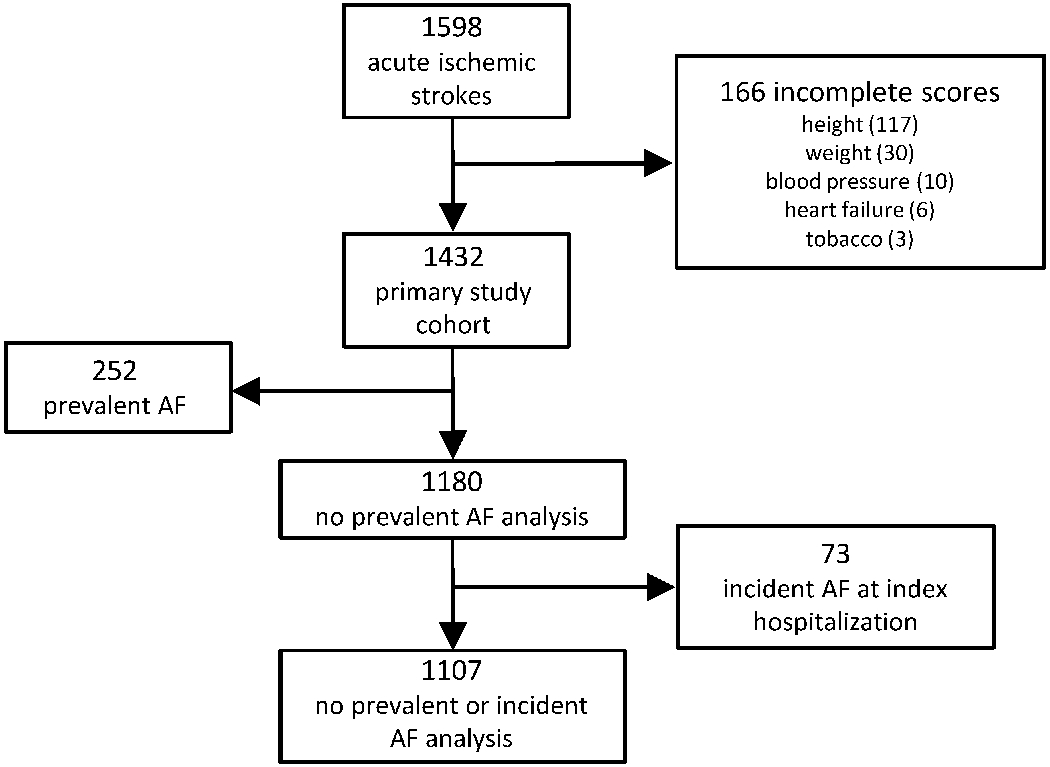

This study is a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data. Between 2002 and 2011, 1,597 patients from Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital were enrolled in a prospective ischemic stroke registry with manual assignment of stroke subtypes (see below). Of these, we excluded 166 with insufficient data to calculate each AF risk score, resulting in 1,431 patients in the primary analysis (Figure 1). Given our intent to quantify the discriminative ability of AF risk as a surrogate for cardioembolism, we included individuals with prevalent AF in our primary analysis and utilized gold-standard stroke subtyping by stroke neurologists. In secondary analyses (see below) we excluded individuals with prevalent AF. The Partners networked healthcare system institutional review board approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects, their legally authorized representatives, or waived via protocol-specific allowance.

Figure 1.

Patient flow through the study.

Flow through the study is depicted.

Stroke classification

All patients underwent routine assessment for ischemic stroke etiology including continuous telemetry monitoring and electrocardiograms. In a retrospective fashion after enrollment and hospital discharge, trained physicians independent of the treating neurologists classified stroke mechanism according to Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST)12 and/or Causative Classification of Stroke (CCS) System criteria13, based on all available clinical data at the time of delayed adjudication. Adjudicators had access to the full medical record of the subjects and completed an online case report form to document TOAST and CCS subtype as part of the phenotyping procedures supported by the NINDS-Stroke Genetics Network (SiGN) initiative, as described previously (details in Supplemental Appendix I).14 Given previous correlation of the TOAST and CCS,15 we defined cardioembolic events as follows: definite cardioembolism (“Definite Cardioembolic” by TOAST, “Cardio-Aortic Embolism Evident” or “Cardio-Aortic Embolism Probable” by CCS), and possible cardioembolism (“Possible Cardioembolic” by TOAST or “Cardio-Aortic Embolism Possible” by CCS). To maximize validity of our cardioembolic stroke classification, we considered possible cardioembolism, in addition to all other strokes not meeting criteria for definite cardioembolism, as non-cardioembolic in the primary analysis.

Comorbidities and AF risk estimation

We obtained patient age, sex, and race from the EHR at the time of stroke. Height, weight, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale were obtained from the initial neurologic exam. If weight was not documented, we accepted any weight in the EHR within one year of stroke. If height was not documented, we accepted any height in the EHR. The presence of smoking, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, coronary heart disease, previous stroke or transient ischemic attack, carotid artery disease, and peripheral arterial disease were obtained from the initial neurological history and physical exam. Additional characteristics including prevalent myocardial infarction, heart failure, hypothyroidism, anti-hypertensive drug use, discharge medications, imaging, monitor utilization, and incident AF during stroke hospitalization were obtained by manual EHR review by an adjudicator blinded to stroke subtype. Development of incident AF after discharge was ascertained using a validated algorithm (positive predictive value 88%).16 We considered atrial flutter equivalent to AF. We defined chronic kidney disease as creatinine >1.5 mg/dL or glomerular filtration rate <60 mg/min at the time of presentation. Heart failure was defined as chart documentation of heart failure, or left ventricular ejection fraction <50%.17,18 Valvular disease was defined as history of valve repair/replacement, or valvular stenosis/regurgitation of moderate or greater severity on initial echocardiogram.

AF risk for each patient was determined by calculation of the linear predictor of three AF risk scores: CHA2DS2-VASc (range 0-9), CHARGE-AF (range 7.01-17.51), and EHR-AF (range 1.94-10.98). Although derived and validated for stroke prediction in AF, we included CHA2DS2-VASc since it is commonly utilized in clinical practice and has been used for AF risk estimation.19 The covariates and weights comprising each score8,9 are shown in Supplemental Tables I–III.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared using t-tests or Fisher’s exact test. To assess for an association between AF risk and cardioembolic stroke, we regressed the log-odds of cardioembolism on each score using logistic regression. To facilitate comparisons, models were not adjusted for additional covariates, and scores were mean-centered and variance-standardized. We assessed discrimination of AF risk for cardioembolic stroke by generating receiver operating characteristic curves and calculating c-statistics. In the absence of a previously-determined positivity criterion for AF risk as a classifier for cardioembolism, we determined score thresholds with 70, 80, 90, 95, and 99% sensitivity and specificity for cardioembolism and determined corresponding likelihood ratios. In secondary analyses, we computed predicted probabilities of AF using CHARGE-AF and EHR-AF scores and determined test characteristics across quantiles of AF risk.

Given our intent to assess the utility of AF risk as a cardioembolism classifier in individuals with acute stroke, we simulated the results of an AF risk-guided approach in a hypothetical cohort of undifferentiated stroke patients (i.e., without diagnosed AF). Since the distribution of stroke subtypes varies across populations, we sought to assess the performance of AF risk across simulated populations with varying cardioembolism prevalence.20 Therefore, we projected the test characteristics of EHR-AF (chosen due to strongest association with cardioembolic stroke) onto a hypothetical sample of individuals with underlying cardioembolism prevalence 5-30%, the range of prevalence observed in previous studies.5,20,21 We then empirically applied the test characteristics of the EHR-AF score at the 90%, 95%, and 99% sensitivity and specificity thresholds across the spectrum of simulated cardioembolism prevalence to determine the resulting posterior probabilities of cardioembolism.22

To assess whether associations between AF risk and cardioembolic stroke were driven solely by the presence of known or clinically apparent AF, we performed sensitivity analyses excluding patients with prevalent AF at the time of stroke, and additionally patients who developed incident AF during stroke hospitalization. The potential utility of AF risk as a cardioembolism classifier is likely related to the ability to predict a future AF diagnosis. We therefore performed secondary analyses assessing whether AF risk was associated with cardioembolism among individuals who developed AF after stroke, and also whether AF risk predicted incident AF after stroke using Cox proportional hazards regression. To assess whether observed associations between AF risk and cardioembolic stroke varied according to stringency of cardioembolism definition, we also performed sensitivity analyses in which we considered both definite (“Definite Cardioembolic” by TOAST, “Cardio-Aortic Embolism Evident” or “Cardio-Aortic Embolism Probable” by CCS) and possible (“Possible Cardioembolic” by TOAST or “Cardio-Aortic Embolism Possible” by CCS) cardioembolic events as cardioembolic. Given known associations between AF and older age, we assessed the value of age alone in discriminating cardioembolism. All modeling was performed using a complete case approach to maximize score comparability (Figure 1). Analyses were performed using R v3.5 (packages epitools, plyr, pROC).23 A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 1,597 individuals with acute ischemic stroke, 1,431 had complete data for AF risk estimation and were included in the primary analysis (Figure 1). Characteristics of individuals excluded for missing data are listed in Supplemental Table IV. Of 1,431 in the primary analysis, the mean (±SD) age was 65.1±15.3 years and 40.4% were female. The mean CHA2DS2-VASc, CHARGE-AF, and EHR-AF scores were 2.89±1.9, 13.1±1.8, and 7.57±1.6, respectively. Almost all patients were treated with an antiplatelet (69%), anticoagulant (37%), or both (12%). Other sample characteristics are listed in Table 1. AF was prevalent at stroke in 255 (17.8%), incident during stroke hospitalization in 71 (5.0%) and incident after discharge in 194 (13.6%). AF risk scores stratified by AF status are displayed in Supplemental Table V.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of stroke sample stratified by mechanism

| N (%) or Mean ± SD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cohort | Cardioembolic | Non-cardioembolic | ||

| Demographics | N=1,431 | N=323 | N=1,108 | p |

| Female *†‡ | 578 (40.4%) | 149 (46.1%) | 429 (38.7%) | 0.02 |

| Age*†‡ | 65.1±15.3 | 72.4±13.2 | 63.0±15.3 | <0.01 |

| White race†‡ | 1328 (92.8%) | 303 (93.8%) | 1025 (92.5%) | 0.47 |

| Stroke Characteristics | ||||

| NIH Stroke Scale | 4.90±5.95 | 7.30±7.00 | 4.21±5.42 | <0.01 |

| Antiplatelet at discharge | 989 (69.1%) | 178 (55.1%) | 811 (73.2%) | <0.01 |

| Anticoagulant at discharge | 530 (37.0%) | 202 (62.5%) | 328 (29.6%) | <0.01 |

| Statin at discharge | 889 (62.1%) | 200 (61.9%) | 689 (62.2%) | 0.95 |

| Potential AF risk factors | ||||

| Height, cm†‡ | 170.6±10.7 | 170.0±11.4 | 170.8±10.5 | 0.29 |

| Weight, kg†‡ | 81.4±19.0 | 79.6±18.5 | 81.9±19.2 | 0.05 |

| Current smoking†‡ | 274 (19.1%) | 42 (13.0%) | 232 (20.9%) | <0.01 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg† | 151±29 | 150±28 | 151±29 | 0.63 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg†‡ | 80±16 | 79±17 | 80±15 | 0.30 |

| Hypertension*‡ | 891 (62.3%) | 213 (65.9%) | 678 (61.2%) | 0.13 |

| Anti-hypertensive medication† | 857 (59.9%) | 235 (72.8%) | 622 (56.1%) | <0.01 |

| Diabetes*†‡ | 302 (21.1%) | 71 (22.0%) | 231 (20.8%) | 0.70 |

| Hyperlipidemia‡ | 594 (41.5%) | 140 (43.3%) | 454 (41.0%) | 0.48 |

| Previous stroke/TIA*‡ | 310 (21.7%) | 74 (22.9%) | 236 (21.3%) | 0.54 |

| Heart failure*†‡ | 193 (13.5%) | 98 (30.3%) | 95 (8.57%) | <0.01 |

| Valvular disease‡ | 183 (12.8%) | 110 (34.0%) | 73 (6.59%) | <0.01 |

| Hypothyroidism‡ | 132 (9.22%) | 37 (11.4%) | 95 (8.57%) | 0.13 |

| Vascular disease* | ||||

| Coronary heart disease‡ | 301 (21.0%) | 100 (31.0%) | 201 (18.1%) | <0.01 |

| Carotid artery disease | 83 (5.80%) | 13 (4.02%) | 70 (6.31%) | 0.14 |

| Peripheral artery disease‡ | 141 (9.85%) | 30 (9.29%) | 111 (10.0%) | 0.75 |

| Myocardial infarction† | 175 (12.2%) | 67 (20.7%) | 108 (9.75%) | <0.01 |

| Chronic kidney disease‡ | 534 (37.3%) | 172 (53.3%) | 362 (32.7%) | <0.01 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 2.89±1.9 | 3.66±1.8 | 2.67±1.9 | <0.01 |

| CHARGE-AF score | 13.1±1.8 | 14.0±1.4 | 12.8±1.8 | <0.01 |

| EHR-AF score | 7.57±1.6 | 8.44±1.2 | 7.32±1.6 | <0.01 |

CHA2DS2-VASc component

CHARGE-AF component

EHR-AF component

Of 1,431 individuals in the sample, 323 (22.6%) had cardioembolic stroke while 1,108 (77.4%) had non-cardioembolic stroke. Of the 1,108 with non-cardioembolic stroke, etiology was large vessel in 339 (23.7%), small vessel in 169 (11.8%), possible cardioembolic in 218 (15.2%), unknown in 96 (6.7%), and other in 286 (20.0%). Patients with cardioembolism had more severe stroke symptoms (mean NIH stroke scale 7.30±7.00 for cardioembolic vs. 4.21±5.42 for non-cardioembolic, p<0.01). Stroke was diagnosed with CT in 1264 (88.3%), MRI in 1284 (89.7%), or both in 1123 (78.5%). Holter/event monitors were deployed within 6 months of stroke and returned for analysis in 790 (55.2%). AF was ultimately diagnosed in 274 (84.8%) individuals with cardioembolic stroke (prevalent in 196 [60.7%], incident during stroke hospitalization in 54 [16.7%], incident after discharge in 23 [7.12%]). Remaining cases of cardioembolism were attributed to cardiac tumor, endocarditis, or intracardiac thrombus outside the setting of AF. Among individuals with non-cardioembolic stroke, AF was prevalent at stroke in 59 (5.3%), incident during stroke hospitalization in 17 (1.5%), and incident after discharge in 171 (15.4%). Of individuals with non-cardioembolic stroke who had prevalent AF or incident AF during stroke hospitalization, stroke etiologies were large vessel in 17 (22.4%), small vessel in 6 (7.9%), possible cardioembolic in 7 (9.2%), unknown in 9 (11.8%), and other in 37 (48.7%).

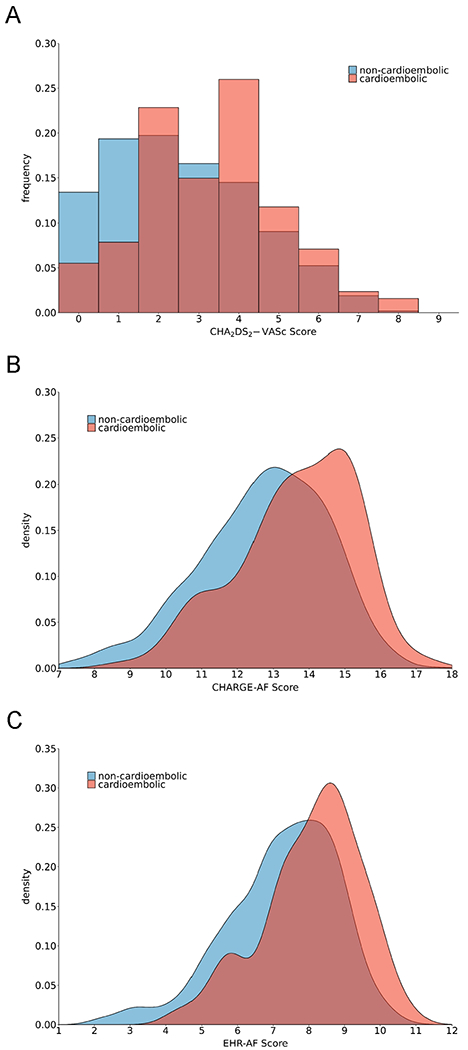

AF risk scores were higher in patients with cardioembolic, as opposed to non-cardioembolic, strokes (mean CHA2DS2-VASc 3.65±1.8 vs. 2.67±1.9, CHARGE-AF 13.97±1.4 vs. 12.80±1.8, EHR-AF 8.43±1.2 vs. 7.32±1.6, respectively, p<0.01 for all). CHA2DS2-VASc, CHARGE-AF, and EHR-AF score distributions stratified by cardioembolic versus non-cardioembolic stroke are depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Distributions of CHA2DS2-VASc, CHARGE-AF and EHR-AF scores stratified by stroke mechanism

The probability distributions of CHA2DS2-VASc (panel A), CHARGE-AF (panel B), and EHR-AF (panel C) scores stratified by stroke mechanism are depicted. Blue shade depicts non-cardioembolic events, while red shade indicates cardioembolic events.

In logistic regression, each AF risk score was associated with cardioembolism (Table 2). Discrimination of cardioembolic from non-cardioembolic stroke varied by score, but was highest using EHR-AF (Table 2). Associations between AF risk and cardioembolic stroke persisted in sensitivity analyses excluding prevalent AF and incident AF during stroke hospitalization, as well as in analyses considering possible cardioembolic stroke within the definition of cardioembolism (Supplemental Tables VI–VIII). Associations between CHARGE-AF and EHR-AF with cardioembolism persisted among individuals who developed incident AF after stroke (Supplemental Table IX). Each AF risk score was predictive of incident AF after stroke (Supplemental Table X). Age alone also discriminated cardioembolism to a moderate extent, although lower than the AF risk scores (Supplemental Table XI).

Table 2.

Associations between AF risk and cardioembolic stroke

| Score | Odds ratio (95%CI) | p-value | C-index (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHA2DS2-VASc (per 1 SD increase) | 1.69 (1.49-1.93) | <0.01 | 0.651 (0.619-0.683) |

| CHARGE-AF (per 1 SD increase) | 2.22 (1.90-2.60) | <0.01 | 0.695 (0.663-0.726) |

| EHR-AF (per 1 SD increase) | 2.55 (2.16-3.04) | <0.01 | 0.713 (0.681-0.744) |

We quantified the test characteristics of AF risk at selected sensitivity and specificity thresholds (Table 3). For example, an EHR-AF score of 6.75 corresponded to 90% sensitivity and 32.4% specificity for cardioembolism with a positive likelihood ratio of 1.31 and negative likelihood ratio of 0.31. Since EHR-AF was designed to estimate incident AF risk in a sample free of baseline AF, we have provided the corresponding 5-year predicted probabilities of AF risk in Supplemental Table XII. Test characteristics at categories and deciles of estimated AF risk are depicted in Supplemental Tables XIII–XIV. The distribution of estimated AF risk according to CHARGE-AF and EHR-AF in the subset of individuals without prevalent AF at the time of stroke are depicted in Supplemental Figure I. Receiver operating characteristic curves for cardioembolism using each AF risk score are shown in Supplemental Figure II.

Table 3.

AF risk score performance for cardioembolic stroke at selected sensitivity and specificity cutoffs

| Score (CE=323, NCE=1109) | Sensitivity Threshold | Corresponding specificity | LR+ | LR− | Score Value | #CE above/below threshold | #NCE above/below threshold | Specificity Threshold | Corresponding sensitivity | LR+ | LR− | Score Value | #CE above/below threshold | #NCE above/below threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHA2DS2-VASc* | 70% | 50.5% | 1.47 | 0.53 | 3 | 236/87 | 549/599 | 70% | 56.7% | 1.73 | 0.64 | 4 | 94/229 | 197/911 |

| 80% | 50.5% | 1.47 | 0.53 | 3 | 236/87 | 549/599 | 80% | 29.1% | 1.64 | 0.86 | 5 | 47/276 | 90/1017 | |

| 90% | 31.3% | 1.28 | 0.39 | 2 | 284/39 | 761/347 | 90% | 14.6% | 1.77 | 0.93 | 6 | 21/302 | 28/1080 | |

| 95% | 12.9% | 1.11 | 0.29 | 1 | 311/12 | 965/143 | 95% | 6.50% | 2.57 | 0.96 | 7 | 6/317 | 4/1104 | |

| 99% | - | 1.00 | - | 0 | 323/0 | 1109/0 | 99% | 1.86% | 5.15 | 0.98 | 8 | 0/323 | 1/1107 | |

| CHARGE-AF | 70% | 58.9% | 1.71 | 0.50 | 13.37 | 227/96 | 455/653 | 70% | 57.3% | 1.91 | 0.61 | 13.90 | 185/138 | 332/776 |

| 80% | 47.3% | 1.52 | 0.42 | 12.85 | 259/64 | 584/524 | 80% | 44.3% | 2.20 | 0.70 | 14.39 | 143/180 | 223/885 | |

| 90% | 30.4% | 1.29 | 0.33 | 11.97 | 291/32 | 771/337 | 90% | 25.4% | 2.56 | 0.83 | 15.00 | 82/241 | 110/998 | |

| 95% | 18.2% | 1.16 | 0.27 | 11.17 | 307/16 | 906/203 | 95% | 12.7% | 2.56 | 0.92 | 15.46 | 41/282 | 55/1053 | |

| 99% | 9.93% | 1.10 | 0.09 | 10.30 | 320/3 | 998/110 | 99% | 2.48% | 2.49 | 0.99 | 16.20 | 8/315 | 11/1097 | |

| EHR-AF | 70% | 59.5% | 1.72 | 0.50 | 7.90 | 226/96 | 449/659 | 70% | 59.1% | 1.96 | 0.58 | 8.32 | 191/132 | 332/776 |

| 80% | 48.7% | 1.55 | 0.41 | 7.45 | 259/64 | 572/536 | 80% | 45.8% | 2.25 | 0.68 | 8.67 | 148/175 | 224/884 | |

| 90% | 32.4% | 1.31 | 0.31 | 6.75 | 292/31 | 765/343 | 90% | 30.0% | 2.97 | 0.78 | 9.13 | 97/226 | 111/997 | |

| 95% | 20.2% | 1.16 | 0.27 | 5.93 | 307/16 | 905/203 | 95% | 20.7% | 4.05 | 0.83 | 9.50 | 67/256 | 56/1052 | |

| 99% | 9.21% | 1.09 | 0.10 | 5.16 | 320/3 | 1006/102 | 99% | 5.88% | 6.18 | 0.95 | 10.15 | 19/304 | 10/1098 | |

CE = cardioembolic stroke, NCE = non-cardioembolic stroke, LR+ = positive likelihood ratio, LR- = negative likelihood ratio

For CHA2DS2-VASc, the score value numerically closest to the desired threshold is displayed. For example, a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 3 has a sensitivity between 70-80%.

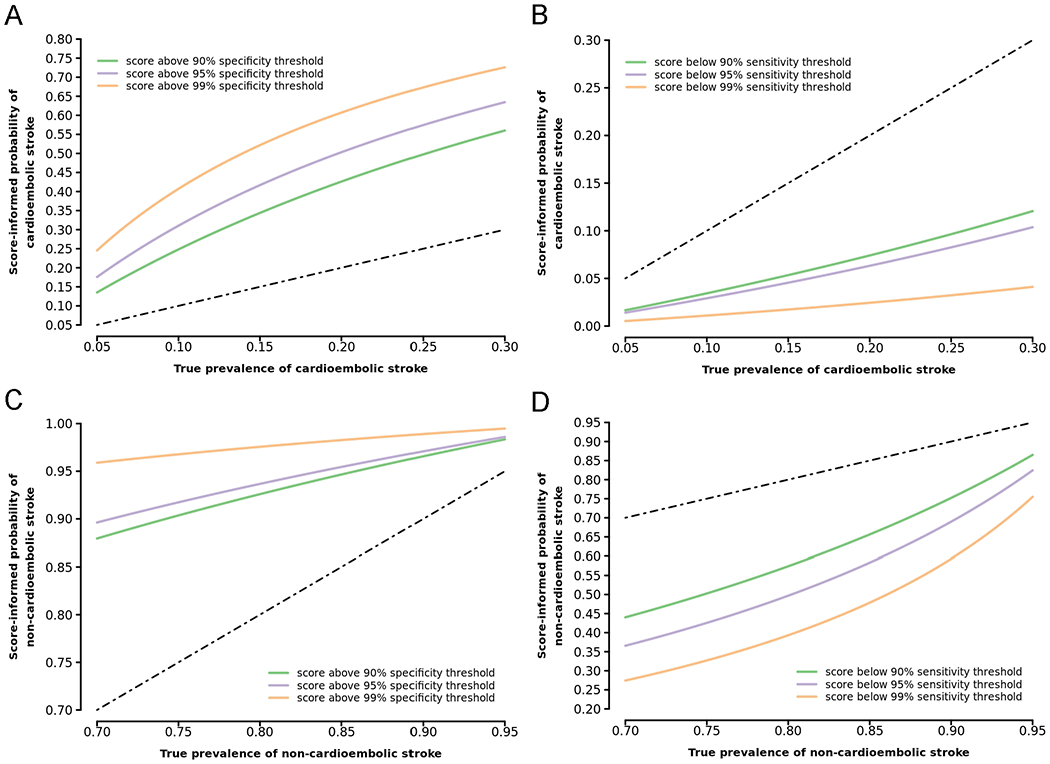

In a hypothetical sample of undifferentiated ischemic strokes, the probability of cardioembolic stroke decreased substantially when utilizing sensitive thresholds of EHR-AF as a “rule-out” test (Figure 3). For example, assuming an underlying cardioembolic stroke prevalence of 20%, individuals with scores not exceeding a 90% sensitive EHR-AF score threshold (i.e., EHR-AF score ≤6.75) have a score-informed probability of cardioembolic stroke below 7.1%. In our sample, 374 (26.1%) individuals had EHR-AF scores below this threshold. The probability of cardioembolic stroke increased more modestly when utilizing specific thresholds of EHR-AF as a “rule-in” test (Figure 3). For example, assuming an underlying cardioembolic stroke prevalence of 20%, individuals with scores exceeding a 90% specific EHR-AF score threshold (i.e., EHR-AF score >9.13) have a score-informed probability of cardioembolic stroke above 42.6%. In our sample, 208 (14.5%) individuals had scores beyond this threshold.

Figure 3.

Predictive value of EHR-AF score for cardioembolic and non-cardioembolic stroke in a simulated undifferentiated ischemic stroke cohort

The EHR-AF score-informed probabilities of cardioembolic and non-cardioembolic stroke are depicted along increasing true prevalence of cardioembolic and non-cardioembolic stroke in a simulated cohort of undifferentiated ischemic stroke patients. EHR-AF thresholds sensitive for cardioembolic and specific for non-cardioembolic stroke are depicted in Panels A and D, respectively, to illustrate the use of the EHR-AF score to identify patients at low risk for cardioembolism (and high risk for non-cardioembolism). EHR-AF thresholds specific for cardioembolic and sensitive for non-cardioembolic stroke are depicted in Panels B and C, respectively, to illustrate the potential use of the EHR-AF score to identify patients at high risk of cardioembolism (and low risk for non-cardioembolism). At a given true prevalence on the x-axis, the corresponding score-informed probability on the y-axis at each threshold curve is the probability of the given stroke subtype in an individual with an EHR-AF score equal to the indicated threshold. Gray dashed lines depict the performance of an uninformative test. The selected cardioembolic stroke true prevalence range (5-30%) reflects rates typically encountered in stroke cohorts.

Discussion

In a cross-sectional analysis of 1,431 individuals with adjudicated ischemic stroke, nearly one quarter of events were cardioembolic. AF risk at the time of stroke using CHA2DS2-VASc, CHARGE-AF, and EHR-AF scores was robustly associated with cardioembolic stroke. AF risk had moderate discrimination for cardioembolism, with the EHR-AF score correctly assigning a higher value to those with a cardioembolic stroke in 71% of cases. Importantly, associations between AF risk and cardioembolism persisted after removing individuals with prevalent AF and incident AF during stroke hospitalization. Based on a negative likelihood ratio of 0.31, utilization of a 90% sensitive EHR-AF score threshold as a “rule-out” test reduces the probability of cardioembolic stroke from 20% to 7%, suggesting that AF risk estimation may identify stroke patients at low likelihood of cardioembolism.

The current study supports and extends previous work demonstrating that AF risk is associated with a cardioembolic mechanism among patients without recognized AF presenting with ischemic stroke. We recently demonstrated that the EHR-AF score not only predicts and discriminates AF risk, but also risks of all-cause stroke and stroke prior to AF, a surrogate for AF-related stroke.11 Furthermore, previous studies have shown that AF risk factors including advanced age, left atrial enlargement, and prolonged PR interval predict subsequent AF diagnosis on rhythm monitoring after stroke of unknown origin.24,25 Recent work by our group has also demonstrated that genetic risk of AF is independently associated with cardioembolism.26 Our study adds to previous findings by formally evaluating and quantifying the performance of AF risk as a cardioembolism classifier.

The low negative likelihood ratios observed using sensitive thresholds of AF risk suggest that AF risk estimation may identify stroke patients at very low likelihood of cardioembolism. AF is frequently unrecognized at the time of stroke, and may only be detected after long-term monitoring.5 However, long-term monitoring is resource-intensive, and the majority of patients who undergo monitoring do not have AF.3,27 When utilizing the 90% sensitivity threshold of EHR-AF (corresponding to 2.94% 5-year risk of AF, and including 26% of our sample) as a “rule-out” test, the score-informed probability of cardioembolism remained below 10% even as the underlying prevalence of cardioembolic stroke approached 25%, the upper end of cardioembolism prevalence typically encountered.5,20,21 Our findings suggest that AF risk estimation may allow clinicians to deploy invasive rhythm monitoring more efficiently. Given associated costs, deferral of routine application of invasive or prolonged monitoring in even a small number of patients at low likelihood of cardioembolism may improve cost-effectiveness. Prospective assessment of an AF risk-guided approach to treatment of stroke survivors is warranted.

In contrast, the weaker positive likelihood ratios observed using very specific AF risk thresholds suggest that use of AF risk to identify patients at high risk for cardioembolism may be more limited using current models. For example, when utilizing the 90% specificity threshold of EHR-AF (corresponding to 27.6% 5-year risk of AF, and including 15% of our sample) as a “rule-in” test, the score-informed probability of cardioembolic stroke rose to only 56% even at a cardioembolism prevalence of 30%, a value higher than typically encountered.5,20,21 Furthermore, likely as a result of shared risk factors, non-cardioembolic events remained common even at high thresholds of AF risk.28 Given the bleeding risk associated with anticoagulation, tools to identify cardioembolism as the cause of stroke would need to be extremely accurate to guide empiric anticoagulation. In contrast, application of monitoring tools in patients at elevated, but not definitive, likelihood of cardioembolism would be acceptable. Future efforts may improve the accuracy of AF risk estimation in stroke patients by incorporating additional clinical factors, advanced imaging, biomarkers, and polygenic AF risk.8,25,26,29

Our findings illustrate the value of model complexity in AF risk estimation. Although all three risk scores discriminated cardioembolic stroke, the two more complex scores (CHARGE-AF and EHR-AF) consistently demonstrated superior test characteristics. Given prior findings that CHARGE-AF and EHR-AF predict AF more accurately than CHA2DS2-VASc, it is likely that greater specificity for AF risk results in improved classification of cardioembolic stroke.11,30 Although widespread application of AF risk estimation may have been limited in the past by score complexity, the ubiquity of robust EHR platforms now provides a ready mechanism for automated AF risk estimation. The EHR-AF score, in particular, was built using EHR-based features so it could be deployed to provide automated, real-time AF risk estimation at the point of care. Given the possible utility of estimated AF risk as a cardioembolism classifier, we submit that future studies assessing the added value of equipping stroke physicians with a simple clinical output at the bedside (e.g., composite AF risk) are warranted.

Our study must be interpreted in the context of design. First, retrospective analysis with ascertainment guided by clinical need introduces selection bias. However, all patients underwent routine electrocardiography and telemetry monitoring as part of a standardized stroke evaluation. Second, given our intent to quantify the performance of AF risk as a classifier for cardioembolism in a broad population of stroke patients, we did not exclude prevalent AF in the primary analysis. The presence of known AF or the development of new AF around the time of stroke identifies a patient population at higher AF risk while also increasing the likelihood that a stroke will be classified as cardioembolic. However, the robust association we observed between AF risk and cardioembolic stroke persisted in individuals without prevalent AF or AF diagnosed during the index hospitalization, as well as within individuals who developed AF after stroke. Our findings suggest that a composite of clinical risk factors for AF increases the likelihood of a specific stroke mechanism – cardioembolism – and may therefore have clinical utility among individuals presenting with stroke of unclear etiology. Third, we utilized a complete case analysis, leading to further selection bias. Fourth, although stroke mechanism was adjudicated by trained physicians, misclassification of subtype remains possible. Fifth, although standard echocardiographic parameters generally perform poorly for predicting incident AF, recent data suggest that novel measures including global longitudinal strain and left atrial volume/left ventricular length ratio may have better predictive value for AF in individuals with stroke.29 We did not specifically assess the role of echocardiography for cardioembolism classification. Sixth, given cross-sectional design, we cannot infer causal relations or exclude residual confounding. Seventh, our sample is largely of European ancestry, hails from a single New England metropolitan area, and has a lower proportion of females than previous stroke cohorts, emphasizing the need for replication in other populations.31

In summary, clinical AF risk determined at the time of acute stroke using the CHA2DS2-VASc, CHARGE-AF and EHR-AF scores is associated with the cardioembolic subtype. Discrimination for cardioembolism was best using CHARGE-AF and EHR-AF, with over 70% of patients correctly classified as high risk. Further research is needed to determine whether prospective use of AF risk deployed at the time of stroke leads to more efficient utilization of rhythm monitoring and improved outcomes in patients presenting with stroke of uncertain etiology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

Dr. Lubitz is supported by NIH 1R01HL139731, and Drs. Lubitz, Anderson, and Trinquart are supported by American Heart Association (AHA) 18SFRN34250007. Dr. Anderson is supported by NIH R01NS103924 and grants from the Massachusetts General Hospital. Drs. Ellinor and Benjamin are supported by NIH 1RO1HL092577 and R01HL128914 and by AHA 18SFRN34110082. Dr. Ellinor is supported by NIH K24HL105780 and by Fondation Leducq 14CVD01. Dr. Benjamin was supported by NIH 1R01HL141434 01A1, AHA Tobacco Regulation and Addiction Center (ATRAC) grant U54HL120163-06, and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Dr. Weng is supported by AHA 17POST33660226. Dr. Khurshid is supported by NIH T32HL007208. This work was is in part supported by NIH-NINDS K23NS064052, R01NS082285, and R01NS086905 (Dr. Rost); American Heart Association/Bugher Foundation Centers for Stroke Prevention Research and Deane Institute for Integrative Study of Atrial Fibrillation and Stroke.

Disclosures

Dr. Lubitz receives research support from Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Bayer AG, and Boehringer-Ingelheim, and has consulted for Abbott, Quest Diagnostics, Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer. Dr. Anderson receives research support from Bayer AG and has consulted for ApoPharma, Inc. Dr. Ellinor has consulted for Bayer AG, Novartis, and Quest Diagnostics. Other authors report no disclosures.

Abbreviations

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- EHR

electronic health record

- EHR-AF

electronic health record-based atrial fibrillation score

- CCS

Causative Classification of Stroke

- CHARGE-AF

Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology atrial fibrillation score

- TOAST

Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment

Footnotes

Twitter handles: @shaan_khurshid, @CDAndersonMD, @steven_lubitz

References

- 1.Stewart S, Hart CL, Hole DJ, McMurray JJV. A population-based study of the long-term risks associated with atrial fibrillation: 20-year follow-up of the Renfrew/Paisley study. Am. J. Med. 2002;113:359–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, Hoffman EB, Deenadayalu N, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Lond. Engl 2014;383:955–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanna T, Diener H-C, Passman RS, Di Lazzaro V, Bernstein RA, Morillo CA, et al. Cryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med 2014;370:2478–2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gladstone DJ, Spring M, Dorian P, Panzov V, Thorpe KE, Hall J, et al. Atrial fibrillation in patients with cryptogenic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med 2014;370:2467–2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kishore A, Vail A, Majid A, Dawson J, Lees KR, Tyrrell PJ, et al. Detection of atrial fibrillation after ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2014;45:520–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Afzal MR, Gunda S, Waheed S, Sehar N, Maybrook RJ, Dawn B, et al. Role of Outpatient Cardiac Rhythm Monitoring in Cryptogenic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. PACE. 2015;38:1236–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hart RG, Sharma M, Mundl H, Kasner SE, Bangdiwala SI, Berkowitz SD, et al. Rivaroxaban for Stroke Prevention after Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source. N. Engl. J. Med 2018;378:2191–2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alonso A, Roetker NS, Soliman EZ, Chen LY, Greenland P, Heckbert SR. Prediction of Atrial Fibrillation in a Racially Diverse Cohort: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). J. Am. Heart Assoc 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lip GYH, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJGM. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koene RJ, Alraies MC, Norby FL, Soliman EZ, Maheshwari A, Lip GYH, et al. Relation of the CHA2DS2-VASc Score to Risk of Thrombotic and Embolic Stroke in Community-Dwelling Individuals Without Atrial Fibrillation (From The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities [ARIC] Study). Am. J. Cardiol 2019;123:402–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hulme OL, Khurshid S, Weng L- C, Anderson CD, Wang EY, Ashburner JM, et al. Development and Validation of a Prediction Model for Atrial Fibrillation Using Electronic Health Records. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol 2019;5:1331–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams HP, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, Biller J, Love BB, Gordon DL, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993;24:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arsava EM, Ballabio E, Benner T, Cole JW, Delgado-Martinez MP, Dichgans M, et al. The Causative Classification of Stroke system: an international reliability and optimization study. Neurology. 2010;75:1277–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NINDS Stroke Genetics Network (SiGN), International Stroke Genetics Consortium (ISGC). Loci associated with ischaemic stroke and its subtypes (SiGN): a genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:174–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McArdle PF, Kittner SJ, Ay H, Brown RD, Meschia JF, Rundek T, et al. Agreement between TOAST and CCS ischemic stroke classification: the NINDS SiGN study. Neurology. 2014;83:1653–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khurshid S, Keaney J, Ellinor PT, Lubitz SA. A Simple and Portable Algorithm for Identifying Atrial Fibrillation in the Electronic Medical Record. Am. J. Cardiol 2016;117:221–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banerjee A, Taillandier S, Olesen JB, Lane DA, Lallemand B, Lip GYH, et al. Ejection fraction and outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure: the Loire Valley Atrial Fibrillation Project. Eur. J. Heart Fail 2012;14:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Diepen S, Hellkamp AS, Patel MR, Becker RC, Breithardt G, Hacke W, et al. Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban in patients with heart failure and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: insights from ROCKET AF. Circ. Heart Fail 2013;6:740–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saliba W, Gronich N, Barnett-Griness O, Rennert G. Usefulness of CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc Scores in the Prediction of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation: A Population-Based Study. Am. J. Med 2016;129:843–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai C-F, Thomas B, Sudlow CLM. Epidemiology of stroke and its subtypes in Chinese vs white populations: a systematic review. Neurology. 2013;81:264–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arboix A, Alió J. Cardioembolic stroke: clinical features, specific cardiac disorders and prognosis. Curr. Cardiol. Rev 2010;6:150–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blaha MJ, Cainzos-Achirica M, Greenland P, McEvoy JW, Blankstein R, Budoff MJ, et al. Role of Coronary Artery Calcium Score of Zero and Other Negative Risk Markers for Cardiovascular Disease: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation. 2016;133:849–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.R Core Team (2015). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: URL https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thijs VN, Brachmann J, Morillo CA, Passman RS, Sanna T, Bernstein RA, et al. Predictors for atrial fibrillation detection after cryptogenic stroke: Results from CRYSTAL AF. Neurology. 2016;86:261–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen X, Luo W, Li J, Li M, Wang L, Rao Y, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of STAF, LADS, and iPAB scores for predicting paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in patients with acute cerebral infarction. Clin. Cardiol 2018;41:1507–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pulit SL, Weng L- C, McArdle PF, Trinquart L, Choi SH, Mitchell BD, et al. Atrial fibrillation genetic risk differentiates cardioembolic stroke from other stroke subtypes. Neurol. Genet 2018;4:e293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edwards JD, Kapral MK, Fang J, Saposnik G, Gladstone DJ, Investigators of the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network. Underutilization of Ambulatory ECG Monitoring After Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: Missed Opportunities for Atrial Fibrillation Detection. Stroke. 2016;47:1982–1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang P-S, Pak H-N, Park D-H, Yoo J, Kim T-H, Uhm J-S, et al. Non-cardioembolic risk factors in atrial fibrillation-associated ischemic stroke. PloS One. 2018;13:e0201062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skaarup KG, Christensen H, Høst N, Mahmoud MM, Ovesen C, Olsen FJ, et al. Usefulness of left ventricular speckle tracking echocardiography and novel measures of left atrial structure and function in diagnosing paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack patients. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2017;33:1921–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christophersen IE, Yin X, Larson MG, Lubitz SA, Magnani JW, McManus DD, et al. A comparison of the CHARGE-AF and the CHA2DS2-VASc risk scores for prediction of atrial fibrillation in the Framingham Heart Study. Am. Heart J 2016;178:45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weber R, Krogias C, Eyding J, Bartig D, Meves SH, Katsanos AH, et al. Age and Sex Differences in Ischemic Stroke Treatment in a Nationwide Analysis of 1.11 Million Hospitalized Cases. Stroke. 2019;50:3494–3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.