“We have simple, affordable and proven interventions that save lives. All people around the world should have access to the timely, life-saving care they deserve.” WHO Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus [1].

Improving emergency care saves lives, prevents secondary morbidity and reduces time to recovery. Emergency care presentations are increasing exponentially around the world. Timely recognition and treatment of the acutely ill and injured at the appropriate levels of the health system are fundamental to the quality and safety of healthcare. This is particularly true in the emergency care environment where delivering care is uniquely challenging, particularly for emergency nurses whose practice is starkly different to other nursing specialties [2]. Emergency nurses assess and initiate care for patients of all ages, with varying degrees of clinical urgency and illness severity, most of whom are undiagnosed and undifferentiated. Failure to recognise and respond to clinical deterioration during emergency care increases the incidence of high-mortality adverse events both during emergency care but also following the emergency care episode, irrespective of whether the patient is admitted to hospital or discharged [3], [4].

2020 is the WHO year of the Nurse and Midwife. Nurses are by far the largest proportion of the professional health workforce. Achieving universal health coverage globally will depend on them being able to use their knowledge and skills to the full extent of their scope. Yet they are, too often, undervalued, and their contribution underestimated. Nurses are positioned and poised to facilitate the wider triple impact of improving health, promoting gender equality and supporting economic growth [5] of individuals, families and societies globally.

To achieve this, the World Health Assembly (WHA) 2019 draft resolution recommended emergency care training for all relevant health provider cadres through the creation of speciality training programmes and integrating dedicated emergency care training into undergraduate nursing curricula [1]. The resolution is sympathetic to the shortage of permanent staff assigned to emergency units and the lack of standards for clinical management and documentation but noted that many high-impact improvements in emergency care can be made at very low cost. These include implementing systematic processes to improve the quality of emergency care and save lives. For example, the use of a formal triage protocol in emergency units to prioritize care based on a patient’s needs rather than the order of arrival improves outcomes even where resources are limited. Structured checklists are also known to be an effective low-cost way to enable recognition of life-threatening conditions for critical actions by healthcare personnel [6].

And there lies the evidence practice gap. The lack of structured approaches to comprehensive emergency patient assessment [6]. Standardised patient assessment during emergency care beyond the ABC of Airway, Breathing and Circulation is required. A more comprehensive assessment is crucial. Emergency nurses are responsible for the initial assessment, management and safety of critically ill and injured patients. They are the first and sometimes only clinicians that patients see, so the quality of their initial assessment and ongoing treatment is vital [5]. This is especially so in times of epidemics and pandemics, such as the current COVID-19. Emergency nurses must perform a comprehensive assessment and escalate care to meet the clinical needs of patients. This may also include ordering and interpreting investigations (e.g. pathology tests) and performing interventions (e.g. analgesia) as clinically indicated. The quality and timeliness of emergency nurses’ assessment is crucial as patients seeking emergency care often have extended wait times for medical review. Emergency nurses’ assessment findings underpin clinical decisions by all members of the emergency care team and promotes safe care by preventing, detecting and acting upon deterioration. We propose a nursing solution for emergency care delivery that addresses many of the WHA draft resolutions [1].

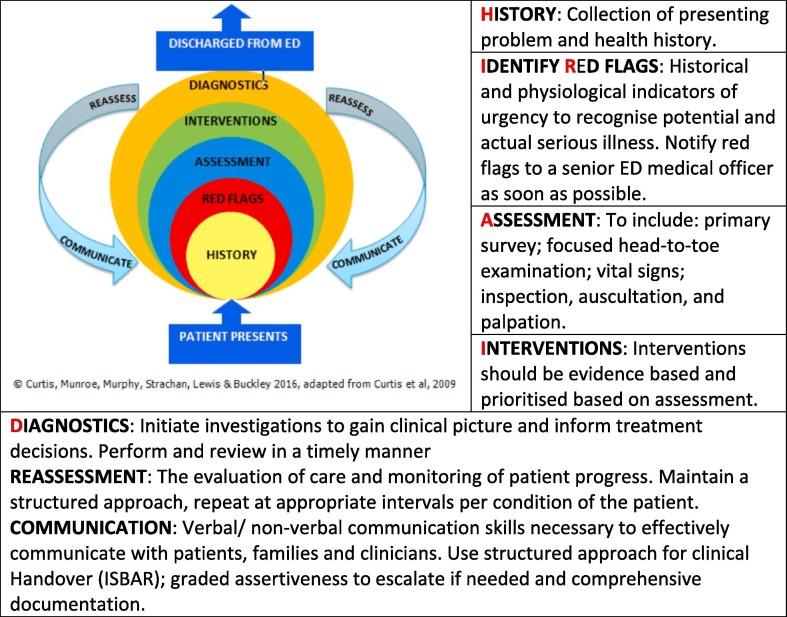

A nursing-led solution for structured assessments in emergency care. HIRAID (History, Identify Red flags, Assessment, Interventions, Diagnostics, communication and reassessment) [7] is a structured emergency assessment framework for application by nurses in any emergency presentation (medical or trauma related) and is based on the best available evidence. HIRAID, illustrated in Fig. 1 , is the only comprehensive assessment framework that can be applied to all patients in the emergency setting [6]. HIRAID improves the quality of patient assessment [8], in particular detection of clinical and historical indicators of urgency. The use of HIRAID also improves the quality and relevance of information collected and handed over to nursing and medical colleagues. Further, the use of HIRAID reduces clinician anxiety and increases self-efficacy [9] which are associated with clinical performance [10], [11]. The operationalisation of HIRAID as a nursing assessment process, and foundation for nurse initiated care protocols could be a tool to meet the WHA recommendations.

Fig. 1.

HIRAID emergency nursing assessment framework [7].

The application of HIRAID is not dependent on context, clinical skill level or resources. It has been formally evaluated in the Australian emergency care environment with the results demonstrating its acceptability, feasibility and practicalilty [12]. Nurses who already use this instrument report it to be a useful, easy to use assessment and documentation tool that provides clinical consistency. The majority of respondents in a multicentre evaluation believed HIRAID is reflective of their responsibilities as emergency nurse. HIRAID is viewed by medical officers as an improvement from previous clinical handover tools [12].

HIRAID is intended to provide a structured approach to application of knowledge and skills in the emergency care environment. It does not replicate existing courses or rely on upskilling. The operationalisation of HIRAID as a basic assessment process, and foundation for nurse-initiated care protocols can be readily adapted for implementation in other international jurisdictions. HIRAID train-the-trainer courses have been delivered in Sri Lanka, Fiji, Nepal and Colombia. However, as HIRAID has only been tested in Australia, it requires formal consultation and evaluation with emergency nurses in low- and middle-income countries. Global intervention in our emergency departments and other emergency care settings will improve emergency nursing assessment, reduce unwarranted variation in care, facilitate timely recognition and response to clinical deterioration, reduce time to treatment, and enable escalation of care as needed. All of which improves the quality and safety of health care for patients.

Contributor Information

Kate Curtis, Email: kate.Curtis@sydney.edu.au.

Ramon Z. Shaban, Email: ramon.shaban@sydney.edu.au.

Margaret Fry, Email: Margaret.Fry@uts.edu.au.

Julie Considine, Email: julie.considine@deakin.edu.au.

Fanny Esperanza Acevedo Gamboa, Email: facevedo@javeriana.edu.co.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Seventy-Second World Health Assembly Draft Resolution (WHA72.16/A72/A/CONF./1). Emergency and trauma care. Emergency care systems for universal health coverage: ensuring timely care for the acutely ill and injured. Geneva 2019.

- 2.Fry M. Chapter 1: emergency nursing in Australia and New Zealand. In: Curtis K., Ramsden C., Shaban R., Fry M., Considine J., editors. Emergency and trauma care: for nurses and paramedics. 2nd ed. Elsevier Australia; Chatswood NSW: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Considine J., Jones D., Pilcher D., Currey J. Patient physiological status during emergency care and rapid response team or cardiac arrest team activation during early hospital admission. Eur J Emerg Med. 2017;24(5):359–365. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forster A.J., Rose N.G.W., Van Walraven C., Stiell I. Adverse events following an emergency department visit. Qual Safety Health Care. 2007;16(1):17–22. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.017384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.All-Party Parliamentary Group on Global Health. Triple Impact – how developing nursing will improve health, promote gender equality and support economic growth. London 2016.

- 6.Munroe B., Curtis K., Considine J., Buckley T. The impact structured patient assessment frameworks have on patient care: an integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(21–22):2991–3005. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munroe B., Curtis K., Margerat M., Strachan L., Buckley T. HIRAID: an evidence-informed emergency nursing assessment framework. Austr Emerg Nurses J. 2015;18(2):83–97. doi: 10.1016/j.aenj.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munroe B., Curtis K., Murphy M. A structured framework improves clinical patient assessment and non-technical skills of early career emergency nurses: a pre-post study using full immersion simulation. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(15–16):2262–2274. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munroe B., Buckley T., Curtis K. The impact of HIRAID on emergency nurses’ self-efficacy, anxiety and perceived control: a simulated study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2016;25:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hollingsworth E., Ford-Gilboe M. Registered nurses’ self-efficacy for assessing and responding to woman abuse in emergency department settings. Can J Nurs Res. 2006;38(4):55–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheung R., Au T. Nursing students' anxiety and clinical performance. J Nurs Educ. 2011;50(5):286–289. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20110131-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis K., Munroe B., Van C., Elphick T.-L. The implementation and usability of HIRAID, a structured approach to emergency nursing assessment. Austr Emerg Care. 2020;23(1):62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.auec.2019.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]