Abstract

BACKGROUND

High sodium (Na+) intake augments blood pressure variability (BPV) in normotensive rodents, without changes in resting blood pressure (BP). Augmented BPV is associated with end-organ damage and cardiovascular morbidity. It is unknown if changes in dietary Na+ influence BPV in humans. We tested the hypothesis that high Na+ feeding would augment BPV in healthy adults.

METHODS

Twenty-one participants (10 F/11 M; 26 ± 5 years; BP: 113 ± 11/62 ± 7 mm Hg) underwent a randomized, controlled feeding study that consisted of 10 days of low (2.6 g/day), medium (6.0 g/day), and high (18.0 g/day) salt diets. On the ninth day of each diet, 24-h urine samples were collected and BPV was calculated from 24-h ambulatory BP monitoring. On the tenth day, in-laboratory beat-to-beat BPV was calculated during 10 min of rest. Serum electrolytes were assessed. We calculated average real variability (ARV) and standard deviation (SD) as metrics of BPV. As a secondary analysis, we calculated central BPV from the 24-h ambulatory BP monitoring.

RESULTS

24-h urinary Na+ excretion (low = 41 ± 24, medium = 97 ± 43, high = 265 ± 92 mmol/24 h, P < 0.01) and serum Na+ (low = 140.0 ± 2.1, medium = 140.7 ± 2.7, high = 141.7 ± 2.5 mmol/l, P = 0.009) increased with greater salt intake. 24-h ambulatory ARV (systolic BP ARV: low = 9.5 ± 1.7, medium = 9.5 ± 1.2, high = 10.0 ± 1.9 mm Hg, P = 0.37) and beat-to-beat ARV (systolic BP ARV: low = 2.1 ± 0.6, medium = 2.0 ± 0.4, high = 2.2 ± 0.8 mm Hg, P = 0.46) were not different. 24-h ambulatory SD (systolic BP: P = 0.29) and beat-to-beat SD (systolic BP: P = 0.47) were not different. There was a trend for a main effect of the diet (P = 0.08) for 24-h ambulatory central systolic BPV.

CONCLUSIONS

Ten days of high sodium feeding does not augment peripheral BPV in healthy, adults.

CLINICAL TRIALS REGISTRATION

Keywords: blood pressure, blood pressure variability, central blood pressure variability, hypertension, salt

The American Heart Association recommends no more than 2,300 mg of sodium (Na+) per day and 1,500 mg Na+ per day for at-risk populations and for overall optimal health.1 On average, Americans consume 3,400 mg Na+ per day,2 increasing the risk of adverse cardiovascular events, independent of changes in resting blood pressure (BP).3 Data from salt-resistant, normotensive rodents4 suggest that excess dietary salt intake increases spontaneous fluctuations of BP, termed BP variability (BPV). Importantly, increased BPV is associated with adverse cardiovascular risks/effects in humans.5 However, there are limited data regarding the impact of dietary salt intake on BPV in healthy humans.

BPV is primarily controlled by central and reflex autonomic modulation and can be effected by emotional states, behavioral (i.e., physical activity and sleep) and humoral systems.6 BPV can be characterized by short-term fluctuations on a beat-to-beat basis and over a 24-h period using 24-h ambulatory BP monitoring.7 Augmented BPV is associated with the development of target organ damage,8 cerebrovascular events,9 carotid atherosclerosis,10 and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.11 Thus, despite the fact that current BP guidelines12 do not provide recommendations on targeting BPV, there are important clinical implications to determining if high dietary salt intake augments BPV in humans.

One study examining patients with hypertension determined that 24-h urinary Na+ excretion was positively correlated to 24-h BPV13 suggesting that dietary salt intake may impact BPV. However, this study examined habitual salt intake and was not a controlled feeding study comparing BPV following various levels of dietary salt. Although our group has previously shown that hypertonic saline infusions and high salt feeding alters autonomic control of BP, including exaggerated sympathetic responses to perturbations and altered baroreflex sensitivity,14–16 the effect of high dietary salt consumption on BPV in healthy young adults is unclear. Given the high dietary salt consumption in the United States2 and that high dietary salt in rodents increases BPV,4 we sought to determine if high dietary salt augments BPV in healthy young adults following 10 days of controlled feeding on low-, medium-, and high-salt diets. We used 24-h ambulatory BP monitoring and laboratory-based beat-to-beat BP measures to comprehensively assess BPV. We hypothesized that increasing levels of dietary salt would augment beat-to-beat and 24-h ambulatory BPV in healthy young individuals. Because central BP provides additional prognostic information17,18 compared with brachial BP alone, we also sought to determine if dietary salt influences indices of central BPV as a secondary analysis. We hypothesized that greater dietary salt would also augment indices of central BPV.

METHODS

Participants

The study protocol procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Delaware and conform to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 (as revised in 1983). The data reported here are part of an ongoing registered clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02881515). Written and verbal consent were obtained from all participants. All participants provided a complete medical history during screening. Screening included determination of height and weight for calculation of body mass index (kg/m2). Oscillometric assessment of BP (Welch Allyn Spot LXi, Skaneateles Falls, NY) was performed in triplicate after a minimum of 5 min of quiet sitting with participant’s legs and back supported. The average of the three measures is reported here. Individuals with abnormal results from a resting 12-lead electrocardiogram or those with abnormal glucose, lipid levels, and biochemical indices of kidney or liver function were excluded. Exclusion criteria also included a history of a hypertension diagnosis, cardiovascular disease, malignancy, diabetes mellitus, renal impairment, and pregnancy. Participants who were obese (body mass index >30 kg/m2) or used tobacco products were also excluded.

Controlled salt diets

Participants completed three 10-day controlled dietary feeding conditions in random order with at least a 4-week washout between trials. A registered dietitian prepared diets in a designated research kitchen that were either low (2.6 g NaCl/day or 1.0 g Na+/day), medium (6.0 g NaCl/day or 2.3 g Na+/day), and high (18 g NaCl/day or 7 g Na+/day) in dietary salt. A sample diet is presented in the supplement. The diets were isocaloric (estimated from the Mifflin-St Jeor formula19) containing 50% carbohydrates, 30% fat, and 20% protein, with potassium fixed at 2.5 g/day.

On the ninth day of each diet, participants collected their urine and wore an ambulatory BP monitor for 24 h preceding the experimental visit on day 10. Participants were instructed to abstain from caffeine and exercise for the 24-h prior to and during the 24-h urine and BP collection. Urine was collected in a light-protected, sterile 3,500 ml container. The total urine volume, urine specific gravity (Goldberg Brix Refractometer, Reichert Technologies, Buffalo, NY), urinary electrolytes (EasyElectrolyte Analyzer, Medica, Bedford, MA), and urine osmolality (Advanced 3D3 Osmometer, Advanced Instruments, Norwood, MA) were assessed from a mixed aliquot of the 24-h collection container. Urine flow rate was calculated and used to determine 24-h Na+ excretion. Ambulatory BP (Oscar 2 with SphygmoCor, SunTech Medical, Morrisville, NC) was monitored every 20 min during the day (0601–2,200 h) and every 30 min at night (2,201–6,000 h). This device has been validated for brachial BP measurement.20 The SunTech Oscar 2 ambulatory BP monitors also report central BP with each brachial BP recording using the same validated algorithm as tonometry-based SphygmoCor products.21 Participants self-reported sleep and wake times in the laboratory to note the start of “daytime” and “nighttime” for the BP values. Given that there is no standard, clinically accepted definition of salt-sensitivity, our laboratory defines salt sensitive as a change in 24-h mean arterial pressure of >5 mm Hg from the low- to the high-salt diet.22,23

Study visit

On the tenth day of the diet, participants reported to the laboratory after at least a 4 h fast. Investigators were blinded to participant’s diet assignment during data collection and analysis. A spot urine sample was obtained to check for pregnancy in female participants. Body mass was determined (TNF-300A, Tanita, Tokyo, Japan). Participants were instrumented for heart rate assessment with a single-lead electrocardiogram and oscillometric BP was assessed with an upper arm cuff placed on the dominant arm (Dash 2000, GE medical Systems, Chicago, IL). An intravenous blood catheter was placed in participant’s dominant arm. Beat-to-beat BP was assessed via servocontrolled photoplethysmography (Finometer, Finapres Medical Systems, Enschede, Netherlands). A cuff was placed on the middle finger of the participant’s nondominant arm. Consistent with previous beat-to-beat BPV assessments,24 participants were supine for 10 min prior to testing. Data were collected during a 10-min baseline period as participants rested quietly in a dimly lit, temperature-controlled room (22–24 °C).

Blood pressure variability

24-h ambulatory BPV and beat-to-beat BPV were assessed. We analyzed ambulatory BP data that had at least 15 measurements during the daytime and at least 8 measurements during the nighttime.25 Beat-to-beat BPV was calculated over 10 min of quiet rest in the laboratory. We assessed BPV using standard deviation (SD) and average real variability (ARV). Although SD of ambulatory BP monitoring is associated with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,26,27 ARV of BP is a more reliable representation of BPV than SD.28 ARV expresses the absolute difference of consecutive measurements and is calculated using the following formula28:

where N stands for the number of BP readings, k is the order of measurements, and w is the time interval between BPk and BPk+1.

Statistical analysis

Beat-to-beat BP and electrocardiogram signals were recorded continuously (LabChart Pro 8, AD Instruments, Sydney, Australia) at 20,000 Hz and stored for offline analysis. Our statistical approaches were informed by recent guidelines for statistical reporting of cardiovascular research.29 Repeated measures one-way analysis of variance were used to compare biochemical and resting hemodynamic markers across the three dietary interventions. The differences in the BPV indices following the diets were examined using a generalized linear mixed-model analysis with repeated measures for diet and time. When appropriate, a Tukey’s post hoc test was performed for pairwise comparisons. We tested data for normality. Data that did not pass normality were analyzed using a nonparametric test. To explore potential sex differences, we employed two-way analysis of variance to compare BPV across the three dietary interventions in male and female participants. Significance was set at P < 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistics were completed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Twenty-one nonhypertensive and nonobese individuals (11 male and 10 female participants) completed the study (Table 1). All but three female participants were classified as salt-resistant. Three of the 10 female participants were taking oral contraceptives throughout the study. Table 2 presents the biochemical and resting BP changes from the dietary salt manipulations. 24-h urinary Na+ excretion increased in a stepwise fashion from the low-, to the medium-, to the high-salt diet, confirming compliance with the diets. Serum sodium was higher following the high-salt diet compared with the low-salt diet. Plasma osmolality was not different following the three diets. Resting brachial BP was also not different following the three diets. Ambulatory BP measures are presented in Table 3. Absolute ambulatory BPs were not different across the three diets.

Table 1.

Participants

| Screening characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Number (F/M) | 21 (10/11) |

| Race/ethnicity (W/L/A) | 14/2/5 |

| Age, year | 26 ± 5 |

| Body mass, kg | 68 ± 11 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25 ± 3 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 113 ± 11 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 62 ± 7 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Abbreviations: A, Asian; BP, arterial blood pressure; L, Latino/Hispanic; W, White; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Biochemical and resting hemodynamic measures

| LS | MS | HS | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary sodium excretion | 42 ± 24 | 97 ± 43a | 265 ± 92a,b | <0.01 |

| Urine rate, l/24 h | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.7a | 0.03 |

| 24-h urine specific gravity | 1.015 ± 0.009 | 1.016 ± 0.009 | 1.013 ± 0.006 | 0.61 |

| Spot urine specific gravity | 1.019 ± 0.009 | 1.015 ± 0.009 | 1.015 ± 0.008 | 0.28 |

| Urine osmolality, mOsm/kg/H2O | 504 ± 293 | 429 ± 199 | 531 ± 234 | 0.32 |

| Plasma osmolality, mOsm/kg/H2O | 288.4 ± 3.8 | 288.5 ± 3.9 | 289.0 ± 2.9 | 0.74 |

| Serum sodium, mmol/l | 140.0 ± 2.1 | 140.7 ± 2.6 | 141.7 ± 2.5a | 0.009 |

| Serum chloride, mmol/l | 103.8 ± 3.2 | 103.3 ± 2.0 | 103.7 ± 1.4 | 0.58 |

| Serum potassium, mmol/l | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 0.39 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 112 ± 14 | 112 ± 12 | 113 ± 10 | 0.79 |

| Mean BP, mm Hg | 78 ± 7 | 78 ± 8 | 80 ± 6 | 0.34 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 61 ± 7 | 61 ± 8 | 63 ± 6 | 0.17 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD, paired, one-way analysis of variance.

Abbreviations: BP, arterial blood pressure; LS, low salt; MS, medium salt; HS, high salt; SD, standard deviation.

P < 0.05.

aDifference with low-salt diet.

bDifference with medium-salt diet.

Table 3.

Ambulatory blood pressure measures

| LS | MS | HS | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h systolic BP, mm Hg | 114 ± 8 | 115 ± 8 | 117 ± 8 | 0.15 |

| 24 h diastolic BP, mm Hg | 64 ± 7 | 64 ± 5 | 64 ± 6 | 0.67 |

| Daytime systolic BP, mm Hg | 117 ± 9 | 119 ± 8 | 120 ± 8 | 0.30 |

| Daytime diastolic BP, mm Hg | 67 ± 8 | 67 ± 6 | 68 ± 7 | 0.74 |

| Nighttime systolic BP, mm Hg | 106 ± 7 | 105 ± 8 | 109 ± 12 | 0.17 |

| Nighttime diastolic BP, mm Hg | 56 ± 6 | 56 ± 6 | 57 ± 7 | 0.77 |

| Nighttime systolic BP dipping, % | 10 ± 5 | 13 ± 6 | 10 ± 9 | 0.25 |

| Nighttime diastolic BP dipping, % | 16 ± 7 | 18 ± 8 | 17 ± 7 | 0.74 |

| 24 h central systolic BP, mm Hg | 103 ± 8 | 104 ± 7 | 105 ± 9 | 0.50 |

| 24 h central diastolic BP, mm Hg | 65 ± 7 | 66 ± 6 | 66 ± 7 | 0.56 |

| Daytime central systolic BP, mm Hg | 105 ± 8 | 107 ± 7 | 108 ± 8 | 0.55 |

| Daytime central diastolic BP, mm Hg | 68 ± 8 | 69 ± 7 | 69 ± 6 | 0.98 |

| Nighttime central systolic BP, mm Hg | 96 ± 7 | 96 ± 7 | 98 ± 11 | 0.16 |

| Nighttime central diastolic BP, mm Hg | 58 ± 6 | 58 ± 6 | 58 ± 6 | 0.69 |

| 24 h heart rate, beats/min | 65 ± 10 | 66 ± 10 | 63 ± 9 | 0.14 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Abbreviations: BP, arterial blood pressure; LS, low salt; MS, medium salt; HS, high salt; SD, standard deviation.

Blood pressure variability

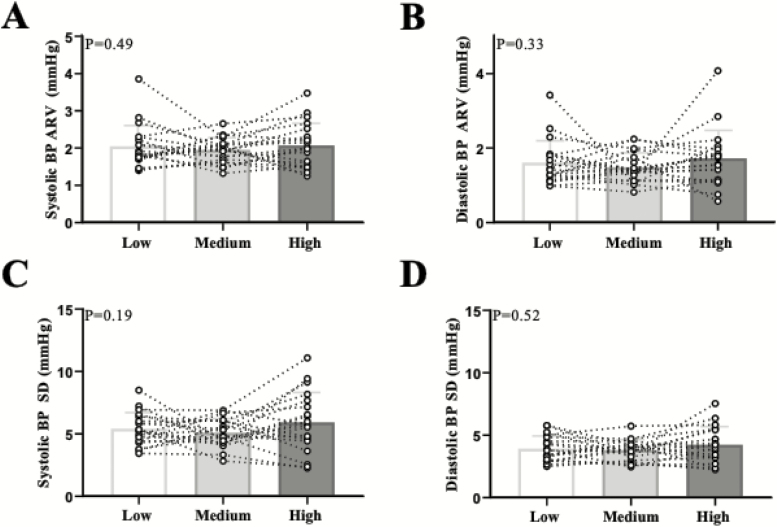

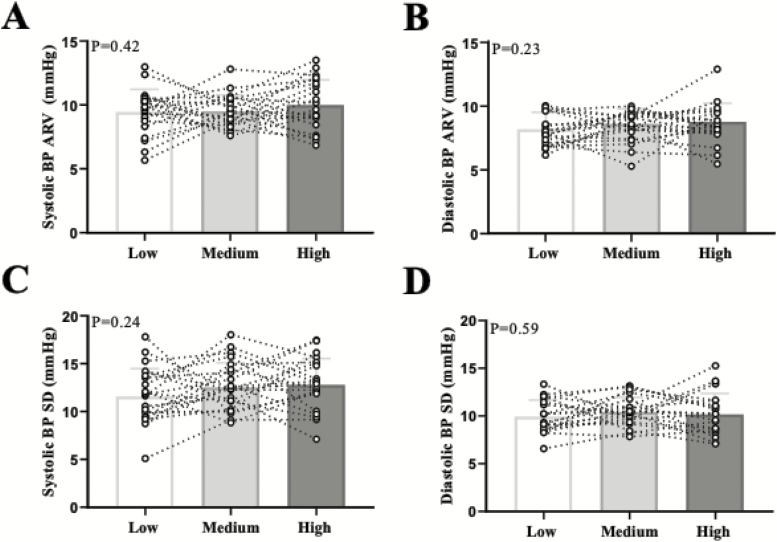

Beat-to-beat systolic and diastolic BP ARV and SD were not different across the three salt diets (Figure 1). Similarly, we did not observe differences in 24-h ambulatory BPV (Figure 2). There were no differences in awake (systolic BP ARV: P = 0.41; diastolic BP ARV: P = 0.77) or asleep (systolic BP ARV: P = 0.73; diastolic BP ARV: P = 0.72) BPV (see Supplementary Table online). We also used the weighted SD approach which eliminates the effects of circadian rhythm.30 There were no differences in weighted SD (systolic BP wSD: P = 0.67; diastolic BP wSD: P = 0.50). There were no sex differences in any BPV metric in the beat-to-beat or 24-h ambulatory BP measurements (data not shown). There was no correlation between urinary Na+ excretion and any metric of BPV (e.g., systolic BP ARV: r2 = 0.01, P = 0.42).

Figure 1.

Individual data points are presented for beat-to-beat systolic BP (a) and diastolic BP (b) average real variability (ARV) and systolic BP (c) and diastolic BP (d) standard deviation (SD) across the three diets. N = 21. Abbreviation: BP, blood pressure.

Figure 2.

Individual data points are presented for 24-h ambulatory systolic BP (a) and diastolic BP (b) average real variability (ARV) and systolic BP (c) and diastolic BP (d) standard deviation (SD) across the three diets. N = 21. Abbreviation: BP, blood pressure.

Central BPV

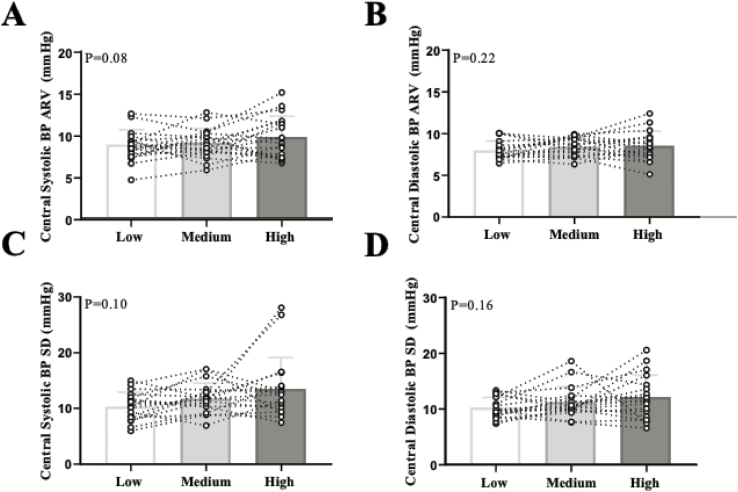

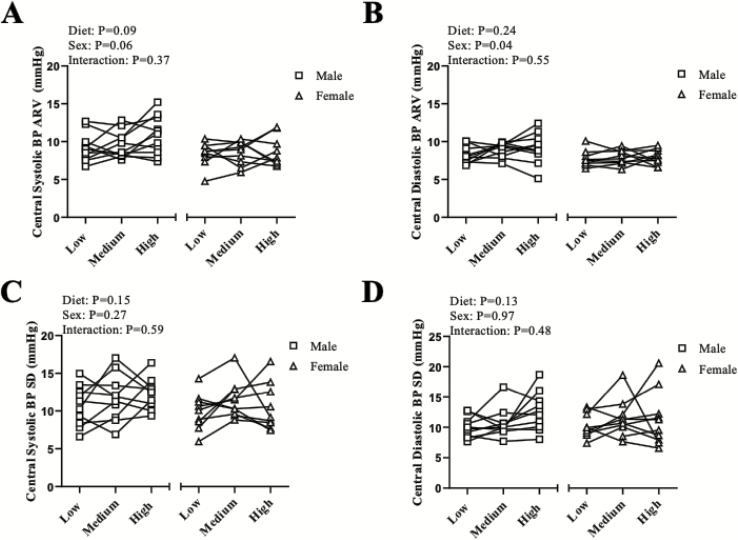

We also examined the effect of dietary salt on central BPV as a secondary aim (Figure 3). When examining the entire cohort, there was a trend for an increase in central systolic BP ARV (P = 0.08). Therefore because of this trend, we examined indices of central ARV (Figure 4a,b) and SD (Figure 4c,d) across male and female participants on an exploratory basis. Although not reaching statistical significance (main effect of sex: P = 0.06), it appears that male participants had an increase in central systolic BP ARV (Figure 4a). There was a main effect of sex (P = 0.04) for central diastolic BP ARV (Figure 4b). There were no sex differences in central systolic BP SD (Figure 4c) or central diastolic BP SD (Figure 4d).

Figure 3.

Individual data points are presented for 24-h ambulatory central systolic BP (a) and central diastolic BP (b) average real variability (ARV) across the three diets. Data are presented for 24-h ambulatory central systolic BP (c) and central diastolic BP (d) SD. N = 21. Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 4.

Individual data points for male and female participants are presented for 24-h ambulatory central systolic BP (a) and central diastolic BP (b) ARV. Individual data points for male and female participants are presented for 24-h ambulatory central systolic BP (c) and central diastolic BP (d) SD. Males N = 11; females N = 10. Abbreviations: ARV, average real variability; BP, blood pressure; SD, standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

The primary novel finding of this study is that high dietary salt intake does not increase BPV compared with medium- or low dietary salt intake in healthy, young, nonhypertensive adults. High dietary salt increased 24-h urinary Na+ excretion in a stepwise manner and increased serum Na+ levels. However, beat-to-beat and 24-h ambulatory BPV were not different between diets. Together, these data suggest that dietary sodium does not influence resting or ambulatory BPV in young, nonhypertensive individuals.

We chose to comprehensively assess BPV using both beat-to-beat laboratory BP and 24-h ambulatory BP recordings using SD and ARV, as different BPV metrics correlate with increased risk of cardiovascular events.31 This study was informed by previous findings suggesting that a high-salt diet increases BPV, independent of resting BP, in normotensive rodents4 and that urinary Na+ excretion correlates with BPV in humans with hypertension.13 However, the duration of the dietary salt diets may impact the responses. For example, in rodents, augmented BPV has been reported following 14–17 days of high dietary salt,4 potentially due to sensitization of the rostral ventrolateral medulla increasing sympathetic outflow.4 When rodents were fed a high-salt diet for 1 week, there were no enhanced sympathetic activity or BP responses.32 Thus, potential species differences and time of dietary salt feeding (14–17 days in rodents to increase BPV vs. 9–10 days in the present study) may partially explain why our results do not support our original hypothesis. However, due to subject burden, we chose to do a 10-day dietary sodium feeding study. A prior investigation by Ozkayar et al.13 demonstrated a significant relation between 24-h urinary Na+ excretion and ambulatory systolic and diastolic ARV in adults with hypertension. Thus, it is possible that habitual high dietary sodium consumption may elicit changes in BPV. Nonetheless, this study assessed habitual salt intake and thus a causal relationship between salt intake and BPV cannot be made. Contrary to these findings, another study reported that adults with hypertension and type 2 diabetes had no improvement in BPV following 7 days of salt-restriction in a hospital setting.33 Taken together, these prior findings demonstrate it is possible that 10 days of high dietary salt feeding in our study was not enough time to elicit changes in BPV. Therefore, future studies may be warranted to elucidate if prolonged (i.e., >10 days) dietary salt influences BPV in healthy young adults. Future studies are also needed to assess the impact of high dietary salt on BPV in older individuals and patient populations.

Regarding central BP, the relationship between aortic and brachial BP is not linear and systolic BP varies between the aortic and brachial artery up to 40 mm Hg.17 Aortic BP directly affects target organs such as the kidney and brain.17 Previously, our group, using radial artery applanation tonometry, found that high dietary salt intake leads to an increase in central systolic BP in middle-aged (52 ± 1 years) and in young (27 ± 1 years) normotensive adults with a greater increase observed in the middle-aged adults.34 Therefore, as a secondary aim, we also determined if increasing amounts of dietary salt increases central BPV. While no significant effect was found, there was a trend for an increase in central systolic ARV across the three diets. Thus, we also choose to examine these variables across male and female participants as an exploratory analysis. Interestingly, we found a trend for a sex difference with central systolic BP ARV (main effect of sex: P = 0.06) and a sex difference with central diastolic BP ARV (main effect of sex: P = 0.04) where it appears that male participants had higher central ARV compared with female participants regardless of the diet. Although the results of central systolic ARV did not reach statistical significance for the effect of diet (P = 0.09), it is well documented that BP regulation varies between male and female individuals.35 Male individuals are at a greater risk for cardiovascular disease then premenopausal women36 and therefore more clinical evidence is needed to understand the value of central BPV. While one study found that an increase in both peripheral and central BPV in individuals with hypertension was associated with end-organ damage,37 another group examining central vs. peripheral BPV using 24-h ambulatory monitoring in individuals with hypertension, found that central (i.e., aortic) ARV is better associated with cardiac abnormalities even after adjustments for confounding factors such as age, sex, and hypertension status.38 Thus, there may be clinical implications to measuring central BPV.

In healthy humans, BP follows a circadian pattern characterized by a surge (increase) in the morning and dip (reduction) throughout the nighttime. Previous work from our laboratory found that 7 days of high salt feeding did not blunt nocturnal BP dipping in normotensive male and female participants.39 Consistent with his previous report, we did not observe alterations in dietary salt over 9–10 days to affect nighttime BP dipping or BPV.

There are some limitations to note including not controlling for the menstrual cycle across the diets. Due to the nature of the study design (i.e., preparing the diets for pick up 10 days prior to the experimental visit), we were unable to control for menstrual cycle. Additionally, as baseline measurements were not performed, we do not know the baseline BPV of each participant prior to any dietary sodium manipulation (i.e., under habitual conditions). However, our primary aim was to determine the effects of dietary sodium using controlled feeding on indices of BPV, not the effects of salt manipulation compared with habitual intake. Although we measured urinary sodium excretion on the ninth day of the diet, we cannot be sure that participants complied with the diet each day. In addition, our results are only applicable to young, healthy individuals. While indices of peripheral BPV are linked to worse cardiovascular outcomes,5 central BP is emerging as an important prognostic variable. However, the 24-h ambulatory cuff provides an estimate of central BP derived from the brachial BP waveform. Therefore, the central BPV results need to be interpreted with caution. Our original aim of the study was to assess BPV following dietary salt manipulation in healthy young adults and thus, the sex comparison results should be interpreted with caution given the small sample size in each group.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that 10 days of high dietary salt feeding does not augment peripheral BPV in young, healthy individuals. While dietary salt has other deleterious effects on cardiovascular function,23,34,40 the present results indicate that dietary salt does not influence BPV in healthy young adults.

FUNDING

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 1R01HL128388. This publication was made possible by the Delaware COBRE in Cardiovascular Health, supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences—NIGMS (5 P20 GM113125) from the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1. Sodium | American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/sodium 2017. Accessed 17 December 2018.

- 2. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015–2020. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/. 2015. Accessed 20 June 2018.

- 3. Strazzullo P, D’Elia L, Kandala NB, Cappuccio FP. Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 2009; 339:b4567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Simmonds SS, Lay J, Stocker SD. Dietary salt intake exaggerates sympathetic reflexes and increases blood pressure variability in normotensive rats. Hypertension 2014; 64:583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kikuya M, Hozawa A, Ohokubo T, Tsuji I, Michimata M, Matsubara M, Ota M, Nagai K, Araki T, Satoh H, Ito S, Hisamichi S, Imai Y. Prognostic significance of blood pressure and heart rate variabilities: the Ohasama study. Hypertension 2000; 36:901–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Parati G, Ochoa JE, Lombardi C, Bilo G. Assessment and management of blood pressure variability. Nat Rev 2013; 10:143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN, Jones DW, Kurtz T, Sheps SG, Roccella EJ. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation 2005; 111:697–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Parati G, Bilo G, Valentini M, Bilo G, Valentini M. Blood pressure variability: methodological aspects, physiology, and clinical implications. In Mancia G, Grassi G, Redon J (eds), Manual of Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension, 2nd edn. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2014, pp. 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Verdecchia P, Angeli F, Gattobigio R, Rapicetta C, Reboldi G. Impact of blood pressure variability on cardiac and cerebrovascular complications in hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2007; 20:154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sander D, Kukla C, Klingelhöfer J, Winbeck K, Conrad B. Relationship between circadian blood pressure patterns and progression of early carotid atherosclerosis: a 3-year follow-up study. Circulation 2000; 102:1536–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rossignol P, Kessler M, Zannad F. Visit-to-visit blood pressure variability and risk for progression of cardiovascular and renal diseases. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2013; 22:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC Jr, Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA Sr, Williamson JD, Wright JT Jr. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71:e127–e248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ozkayar N, Dede F, Ates I, Akyel F, Yildirim T, Altun B. The relationship between dietary salt intake and ambulatory blood pressure variability in non-diabetic hypertensive patients. Nefrologia 2016; 36:694–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wenner MM, Rose WC, Delaney EP, Stillabower ME, Farquhar WB. Influence of plasma osmolality on baroreflex control of sympathetic activity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007; 293:H2313–H2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brian MS, Matthews EL, Watso JC, Babcock MC, Wenner MM, Rose WC, Stocker SD, Farquhar WB. The influence of acute elevations in plasma osmolality and serum sodium on sympathetic outflow and blood pressure responses to exercise. J Neurophysiol 2018; 119:1257–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Babcock MC, Brian MS, Watso JC, Edwards DG, Stocker SD, Wenner MM, Farquhar WB. Alterations in dietary sodium intake affects cardiovagal baroreflex sensitivity. Am J Physiol Integr Comp Physiol 2018; 315:R688–R695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McEniery CM, Cockcroft JR, Roman MJ, Franklin SS, Wilkinson IB. Central blood pressure: current evidence and clinical importance. Eur Heart J 2014; 35:1719–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Kizer JR, Lee ET, Galloway JM, Ali T, Umans JG, Howard BV. Central pressure more strongly relates to vascular disease and outcome than does brachial pressure: the Strong Heart Study. Hypertension 2007; 50:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Frankenfield D, Roth-Yousey L, Compher C. Comparison of predictive equations for resting metabolic rate in healthy nonobese and obese adults: a systematic review. J Am Diet Assoc 2005; 105:775–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goodwin J, Bilous M, Winship S, Finn P, Jones SC. Validation of the Oscar 2 oscillometric 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitor according to the British Hypertension Society protocol. Blood Press Monit 2007; 12:113–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Butlin M, Qasem A. Large artery stiffness assessment using SphygmoCor technology. Pulse (Basel) 2017; 4:180–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. DuPont JJ, Greaney JL, Wenner MM, Lennon-Edwards SL, Sanders PW, Farquhar WB, Edwards DG. High dietary sodium intake impairs endothelium-dependent dilation in healthy salt-resistant humans. J Hypertens 2013; 31:530–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lennon-Edwards S, Ramick MG, Matthews EL, Brian MS, Farquhar WB, Edwards DG. Salt loading has a more deleterious effect on flow-mediated dilation in salt-resistant men than women. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2014; 24:990–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wei FF, Li Y, Zhang L, Xu TY, Ding FH, Wang JG, Staessen JA. Beat-to-beat, reading-to-reading, and day-to-day blood pressure variability in relation to organ damage in untreated Chinese. Hypertension 2014; 63:790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. O’Brien E, Coats A, Owens P, Petrie J, Padfield PL, Littler WA, de Swiet M, Mee F. Use and interpretation of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring: recommendations of the British Hypertension Society. BMJ 2000; 320:1128–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pickering TG, James GD. Ambulatory blood pressure and prognosis. J Hypertens Suppl 1994; 12:S29–S33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Verdecchia B, Ciucci G, Schillaci S, Santucci S, Reboldi P. Prognostic significance of blood pressure variability in essential hypertension. Blood Press Monit 1996; 1:3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mena L, Pintos S, Queipo NV, Aizpúrua JA, Maestre G, Sulbarán T. A reliable index for the prognostic significance of blood pressure variability. J Hypertens 2005; 23:505–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lindsey ML, Gray GA, Wood SK, Curran-Everett D. Statistical considerations in reporting cardiovascular research. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2018; 315:H303–H313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bilo G, Giglio A, Styczkiewicz K, Caldara G, Maronati A, Kawecka-Jaszcz K, Mancia G, Parati G. A new method for assessing 24-h blood pressure variability after excluding the contribution of nocturnal blood pressure fall. J Hypertens 2007; 25:2058–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pengo MF, Rossitto G, Bisogni V, Piazza D, Frigo AC, Seccia TM, Maiolino G, Rossi GP, Pessina AC, Calò LA. Systolic and diastolic short-term blood pressure variability and its determinants in patients with controlled and uncontrolled hypertension: a retrospective cohort study. Blood Press 2015; 24:124–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Adams JM, Madden CJ, Sved AF, Stocker SD. Increased dietary salt enhances sympathoexcitatory and sympathoinhibitory responses from the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Hypertension 2007; 50:354–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Iuchi H, Sakamoto M, Suzuki H, Kayama Y, Ohashi K, Hayashi T, Ishizawa S, Yokota T, Tojo K, Yoshimura M, Utsunomiya K. Effect of one-week salt restriction on blood pressure variability in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0144921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Muth BJ, Brian MS, Chirinos JA, Lennon SL, Farquhar WB, Edwards DG. Central systolic blood pressure and aortic stiffness response to dietary sodium in young and middle-aged adults. J Am Soc Hypertens 2017; 11:627–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Joyner MJ, Wallin BG, Charkoudian N. Reply. Exp Physiol 2016; 101:449–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Reckelhoff JF. Gender differences in the regulation of blood pressure. Hypertension 2001; 37:1199–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. de la Sierra A, Pareja J, Yun S, Acosta E, Aiello F, Oliveras A, Vázquez S, Armario P, Blanch P, Sierra C, Calero F, Fernández-Llama P. Central blood pressure variability is increased in hypertensive patients with target organ damage. J Clin Hypertens 2018; 20:266–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chi C, Yu SK, Auckle R, Argyris AA, Nasothimiou E, Tountas C, Aissopou E, Blacher J, Safar ME, Sfikakis PP, Zhang Y, Protogerou AD. Association of left ventricular structural and functional abnormalities with aortic and brachial blood pressure variability in hypertensive patients: the SAFAR study. J Hum Hypertens 2017; 31:633–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brian MS, Dalpiaz A, Matthews EL, Lennon-Edwards S, Edwards DG, Farquhar WB. Dietary sodium and nocturnal blood pressure dipping in normotensive men and women. J Hum Hypertens 2017; 31:145–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Greaney JL, DuPont JJ, Lennon-Edwards SL, Sanders PW, Edwards DG, Farquhar WB. Dietary sodium loading impairs microvascular function independent of blood pressure in humans: role of oxidative stress. J Physiol 2012; 590:5519–5528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.