Abstract

Objective

To characterize the visceral metastasis as a predictive tool for the survival of patients with spinal metastases through an exploratory meta‐analysis.

Methods

Two investigators independently searched PubMed and Embase databases for eligible studies from 2000–2016. The effect estimates for the hazard ratio (HR) or risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were collected and pooled with a random‐ or fixed‐effect model.

Results

In total, 18 eligible studies were retrieved with 5468 participants from nine countries. The overall pooled effect size for HR and RR was 1.50 and 3.79, respectively, which was proved to be statistically significant. In the subgroup of prostate cancer (PCa) and non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), statistical significance and marginal statistical significance was presented for the pooled HR (HR = 1.76, 95% CI 1.35–2.29) and (RR = 1.56, 95% CI 0.99–2.48), respectively. However, in the subgroup of thyroid cancer, breast cancer, and renal cancer, statistical significance was not achieved (HR = 1.17, 95% CI 0.75–1.83, Z = 0.70, P = 0.486). The results did not show any evidence of publication bias.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that visceral metastasis was a significant prognostic factor in patients with spinal metastases as a whole. Interestingly, the onset of visceral metastases differentially impacted the survival in different primary tumors. Therefore, the prognostic value of visceral metastasis might be related to the type of primary tumor.

Keywords: Meta‐analysis, Metastatic spinal cord compression, Prognosis, Survival, Visceral metastasis

Introduction

The prevalence of symptomatic spinal metastasis has increased due to improved treatments and prolonged survival in cancer patients. Approximate 70% of the patients with cancer can develop spinal metastases1, 2, among whom 20% are usually suffering from neurological deficits3, 4. For metastatic spinal cord compression, approximately 10% of such patients would choose to undergo surgical decompression with/without stabilization1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, which can restore neurological function and improve quality of life. However, the mechanism to identify the patients who may benefit maximally from surgical treatment is not yet clear. Thus, decompressive surgery is not indicated for patients with a severely limited lifespan for only a few weeks9, while supportive care or radiotherapy is appropriate10. Therefore, life expectancy drives treatment regimens for spinal metastasis9, 10, 11, 12.

Currently, several prognostic scoring systems have been proposed to predict the life expectancy in patients with metastatic spinal cord compression (MSCC)13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, primarily including several parameters such as general condition, the extent of extraspinal bone metastases, the extent of spinal metastases, visceral metastases, primary tumor, the severity of spinal cord palsy, and pathological fracture. Of these, visceral metastasis is one of the most valuable prognostic factors in several previous studies13, 15.

Although Tomita et al.13, Tokuhashi et al.14, 15, Sioutos et al.16, North et al.17, van der Linden et al.18, Bauer and Wedin19, and Leithner et al.20 regarded visceral metastasis as a critical component of the scoring systems, nearly half of the studies reported controversial results of its prognostic effect on patients. Ju et al.21 demonstrated that visceral metastasis did not associate significantly with the survival in patients with MSCC from prostate cancer. Moreover, Zadnik et al.22 reported that the difference in survival was not significant between patients with visceral metastases (median survival, 25.9 months) as compared to those without visceral metastases (median survival, 28.1 months). In addition, visceral metastasis is considered to be in the terminal stage of their disease, thereby necessitating only palliative treatments. However, Walcott et al.23 concluded that the existence of a progressive systemic disease should not be a contradiction to aggressive surgery. Therefore, visceral metastasis was a controversial prognostic factor in patients with spinal metastases.

The current meta‐analysis is performed with the goal of identifying and quantifying the role of visceral metastasis in predicting the survival time in patients with spinal metastases.

Methods

Collection of Published Literature

We performed a systematic search in PubMed and Embase databases for eligible publications. The following terms were used: “Visceral metastasis,” “Prognosis,” “Survival,” and “Metastatic spinal cord compression.”

Searching strategies for PubMed and Embase were applied as below:

(i) PubMed

#1 Visceral metastasis

#2 lung

#3 prostate

#4 kidney

#5 thyroid

#6 breast

#7 #1#2#3#4#5#6

#8 spinal metastases

#9 #7 AND #8

((((((((lung) OR prostate) OR kidney) OR thyroid) OR breast)) OR Visceral metastasis)) AND spinal metastases

(ii) Embase

#1 ‘Visceral metastasis'/exp OR ‘lung':ab,ti OR ‘prostate':ab,ti OR ‘kidney':ab,ti OR ‘thyroid':ab,ti OR ‘breast':ab,ti

#2 ‘spinal metastases’/exp

#3 #1 AND #2

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Studies

Studies were included if the following criteria were fulfilled: (i) patients were diagnosed with spinal metastases; (ii) patients who received surgery or radiotherapy; (iii) survival outcomes and prognostic factors were analyzed; and (iv) in order to avoid the impact of targeted therapeutic drugs on the results, only published papers in the English language between January 2000 and December 2016 were searched. All the potentially relevant articles were reviewed and extracted independently by two investigators; the disagreements were resolved by discussion, and the consensus was finally reached.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) the nature of the study was a systematic review, basic research, letter to editors, sensitive analysis, or diagnostic study; (ii) there are <10 participants included; (iii) studies with repeated patients' cohorts; and (iv) duplicated studies.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers extracted the data from eligible articles independently, discussed discrepancies, and reached conformity with respect to all parameters. The indispensable information extracted from all primary studies included baseline characteristics (title, author, year of publication, country, period of the study, and study design), participants' characteristics (age, percentage of males, number of involved patients, number of patients with MSCC, and primary tumor type), effect sizes of hazard ratio (HR) or risk ratio (RR) coupled with respective 95% confidence interval (95% CI). In addition, if HR or 95% CI was not estimated directly, related raw data, such as the survival rates of specific time points and Kaplan–Meier survival curves, were collected by Get Data Graph Digitizer software (version 2.25, http://getdata-graph-digitizer.com) that was calculated rather indirectly.

The Excel spreadsheet24 is also used in the calculation. Diversities on the obtained information were deduced, and disagreements were discussed in person. In the event that several cohorts were studied among the similar population, the newest or most impeccable survey was applied.

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS)25 was used to assess the quality of the method and risk of bias by the two researchers independently as described previously. The scale employed a 9‐star system that assessed three domains: patient selection, comparability of the study groups, and ascertainment of the study outcome. A score of 9 stars indicated low risk of bias, whereas 7–8 indicated medium risk of bias, and a score ≤6 indicated a high risk of bias.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Data, extracted into the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, were pooled by an exploratory time‐to‐event meta‐analysis. All recorded HRs or RRs were combined with 95% CI (including statistically significant or non‐significant) from eligible literature, incorporating the HRs re‐calculated from raw data or Kaplan–Meier curves obtained from primary studies that were synthesized narratively. The pooled estimate for HR or RR and 95% CI of visceral metastasis was deduced using the random‐effect or fixed‐effect model26.

The heterogeneity assumption was verified by Q‐test. A significant Q‐test value (P < 0.10) indicated heterogeneity across studies, following which, the random‐effect model would be selected. On the other hand, the fixed‐effect model would be selected. The significance of the pooled effect was determined by the Z‐test (P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant). One‐way sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the stability of the results, termed as a single study in the meta‐analysis that was deleted each time to reflect the influence of the individual dataset on the pooled effect size. An estimate of potential publication bias was carried out by the funnel plot. An asymmetric plot suggested a potential publication bias. The asymmetry of the funnel plot was assessed by Egger's test. The significance of the intercept was determined by the t‐test, as suggested by the Egger's test (P < 0.10 was considered as statistically significant publication bias). Subgroup analyses were performed according to the participants, primary tumor histology, and effect estimates of HR or RR in each study. All statistical tests were performed using Stata (version 13.0, StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, USA) with two‐sided P‐values.

Results

Search Result and Data Extraction

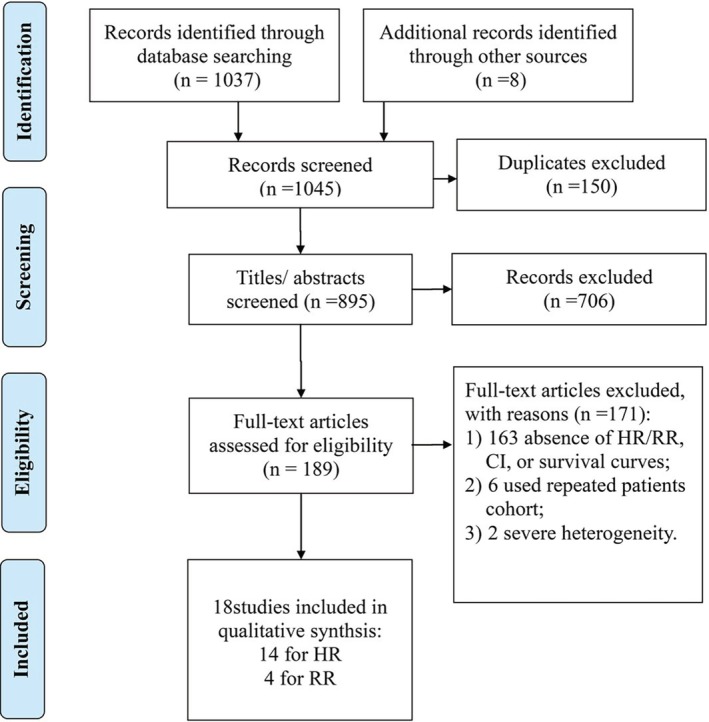

The initial search retrieved 1045 articles. After 150 duplicates were excluded, 895 articles remained. Then, after scrutinizing the titles and abstracts, 706 studies were excluded. A further 163 studies were excluded due to the absence of HR, 95% CI, or survival curves. 1/163 study27 did not present an effect size for HR in multivariate analysis although it significantly originated from visceral metastasis as assessed by univariate analysis and was included in multivariate Cox proportional hazard model. Six studies with the selection of repeated patients were excluded28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33. Another two studies (HR = 199.239, 95% CI 2.615–15180.426 and HR = 5.55, 95% CI 2.39–12.89, respectively)34, 35 were excluded due to severe heterogeneity with other studies according to sensitivity analysis. Finally, 18 studies18, 20, 21, 22, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49 containing 5468 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria, and hence were enrolled in the meta‐analysis that consisted of 14 studies with an effect size for HR and four for RR. The schematic representation of the literature search was shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of studies' identification and selection.

Characteristics of Included Studies

A summary of individual studies was listed in Table 1. In 16 studies with age reported, there were 1883 males and 1535 females, with a mean age of 61.4 years (from 27 to 91 years). The histology of primary tumors varied among 18 studies, with six non‐specified containing 4148 participants, three non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with 470 participants, four prostate cancer with 646 participants, two thyroid cancer with 53 patients, two breast cancer with 130 patients, and one renal cell cancer containing 646 participants. Three thousand seven hundred and ninety‐two patients in 11 studies presented with progressive neurological deterioration by metastatic spinal cord compression. Of those, 2945 patients in four studies18, 45, 47, 48 were treated with radiotherapy alone, 733 patients in five studies21, 36, 37, 40, 49 received surgery plus adjuvant therapy, 64 patients in one study by Lei et al.38 received surgery alone, 50 patients [40] were treated with surgery and other adjuvant therapy. The axial pain was the main clinical symptom in seven studies with 2290 patients. Of those,1493 patients in three studies20, 43, 46 received surgery plus adjuvant therapy, 140 patients in three studies41, 42, 44 with surgery alone, 43 ones22 with surgery and other adjuvant therapy. Studies were conducted in different countries: five in the USA, three in Germany, three in China, three in the Netherlands, and one each in Japan, Sweden, Austria, South Korea, and Dutch. With respect to the delimitation, 17 were retrospective and only one was a semi‐retrospective cohort with prospective manner for assimilation of the information. All studies were high quality with an average score of 7.9 ± 0.9 stars; only one study had a score of 6.0 stars.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies

| Author | Year | Country | Study period | Study design | Patients involved | Patients with MSCC | Male% | Primary tumor | Age (years) | Overall survival | Therapeutic modality | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van der Linden et al.18 | 2005 | Dutch | Mar. 1996–Sept. 1998 | Retrospective cohort | 342 | 12 | 53 | NI | Mean (min‐max): 66 (34–90) | Mean: 11 months; median: 7 months | RT alone | 8 |

| Leithner et al.20 | 2008 | Austria | Jan. 1998–Sept. 2006 | Prospective + retrospective | 69 | NS | 54 | NI | Mean (min‐max): 60 (30–79) | OS% (12 months): 28 median: 14 months | SUR+RT, et al. | 7 |

| Arrigo et al.36 | 2011 | USA | 1999–2009 | Retrospective cohort | 200 | 172 | 61 | NI | Mean (min‐max): 58.9 (19–89) | OS% (1 year, 3 year, 5 year): 38.3, 21.1, 9.41 | SUR+RT, et al. | 9 |

| Chong et al.37 | 2012 | Korea | Mar. 2002–Jun. 2010 | Retrospective cohort | 105 | 105 | 69 | NI | Mean (min‐max): 58.3 (30,87) | Median: 6 months; OS% (1 year, 2 year): 34, 14 | SUR+RT, et al. | 8 |

| Rades et al.45 | 2013 | Germany | 1992–2011 | Retrospective cohort | 2029 | 2029 | NS | NI | NS | OS% (2months): 80 | RT alone | 8 |

| Bollen et al.46 | 2014 | Netherlands | Jan. 2001–Dec. 2010 | Retrospective cohort | 1403 | NS | 52 | NI | Mean: 64.8 (±12.5) | Median: 4.8 months; OS% (6 weeks, 2 year): 77, 17 | SUR/RT/(SUR+RT) | 9 |

| Rades et al.47 | 2012 | Germany | 1992–2010 | Retrospective cohort | 356 | 356 | 74 | NSCLC | Median:64 | OS% (6 months, 12 months): 27.7, 13.5 | RT alone | 9 |

| Lei et al.38 | 2015 | China | May. 2005–May. 2015 | Retrospective cohort | 64 | 64 | 66 | NSCLC | Median:57 | Median: 6.3 months; OS% (6 months, 12 months): 52. 6, 23 | SUR, et al. | 9 |

| Chen et al.39 | 2015 | China | Nov. 2000‐ Mar. 2010 | Retrospective cohort | 50 | 50 | 68 | NSCLC | Mean (min‐max): 61.6 (20–87) | Median: 7.5 months | SUR & other adjuvant therapy | 8 |

| Ju et al.21 | 2013 | USA | Jun. 2002‐ Aug. 2011 | Retrospective cohort | 27 | 27 | 100 | PCa | Median (min‐max): 65 (46,82) | OS% (1 m, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, 12 months): 96, 81, 70, 62, 40 | SUR+RT, et al. | 8 |

| Rades et al.48 | 2012 | Germany | 1992–2010 | Retrospective cohort | 218 | 218 | 100 | PCa | NS | OS% (6 months,12 months): 62.2, 48.9 | RT alone | 7 |

| Crnalic et al.49 | 2012 | Sweden | Sept. 2003–Sept. 2010 | Retrospective cohort | 68 | 68 | 100 | PCa | Median:71 | OS% (3 months, 6 months, 12 months, 24 months): 64, 45, 30, 8 | SUR+RT, et al. | 7 |

| Drzymalski et al.40 | 2010 | USA | Jun. 1990–Apr. 2009 | Retrospective cohort | 333 | 77 | 100 | PCa | Median (min‐max): 68 (43,90) | Median: 24 months OS% (12 months): 73 | SUR/RT, et al. | 8 |

| Bakker et al.43 | 2014 | Netherlands | Jan. 2006–Jul. 2013 | Retrospective cohort | 21 | NS | NS | RCC | NS | Median (min‐max): 25 months (11 months, 75 months) | SUR+RT, et al. | 6 |

| Kato et al. 41 | 2016 | Japan | 1984–2011 | Retrospective cohort | 32 | NS | 22 | TCa | Mean: 60.6 | Median:6.4 year OS% (5 year, 10 year): 71%, 31% | SUR, et al. | 7 |

| Liang et al.42 | 2014 | China | 1999–2013 | Retrospective cohort | 21 | NS | 24 | TCa | NS | NS | SUR, et al. | 7 |

| Sciubba et al.44 | 2007 | USA | Jun. 1993–Jun. 2001 | Retrospective cohort | 87 | NS | 0 | BCa | Median (min‐max): 53 (35,84) | OS% (1 year, 2 year, 3 year, 4 year, 5 year): 62, 44, 33, 27, 24 | SUR, et al. | 9 |

| Zadnik et al.22 | 2004 | USA | Jun. 2002–Aug. 2011 | Retrospective cohort | 43 | NS | 0 | BCa | Median (min‐max): 56 (27,91) | Median:26.8 months | SUR & other adjuvant therapy | 8 |

BCa, breast cancer; MSCC, metastatic spinal cord compression; NI, not identified primary tumor type; NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa Scale; NS, not specified; NSCLC, non‐small cell lung cancer; OS%, percentage of overall survival; PCa, prostate cancer; RCC, renal cell cancer; RT, radiotherapy; SUR, surgery; TCa, thyroid cancer.

Qualitative Summary and Data Synthesis

Among the 18 studies included, only eight studies reported statistically significant results. Moreover, 14 studies presented the effect sizes for HR. Among these studies, all cohorts were involved with surgical procedures except one, wherein only radiotherapy was administered18. In this study, the HR was 1.67 (CI 95% 1.25–2.50), with a significant result (P < 0.001). Additionally, four studies that presented effect sizes for RR were treated with radiotherapy alone.

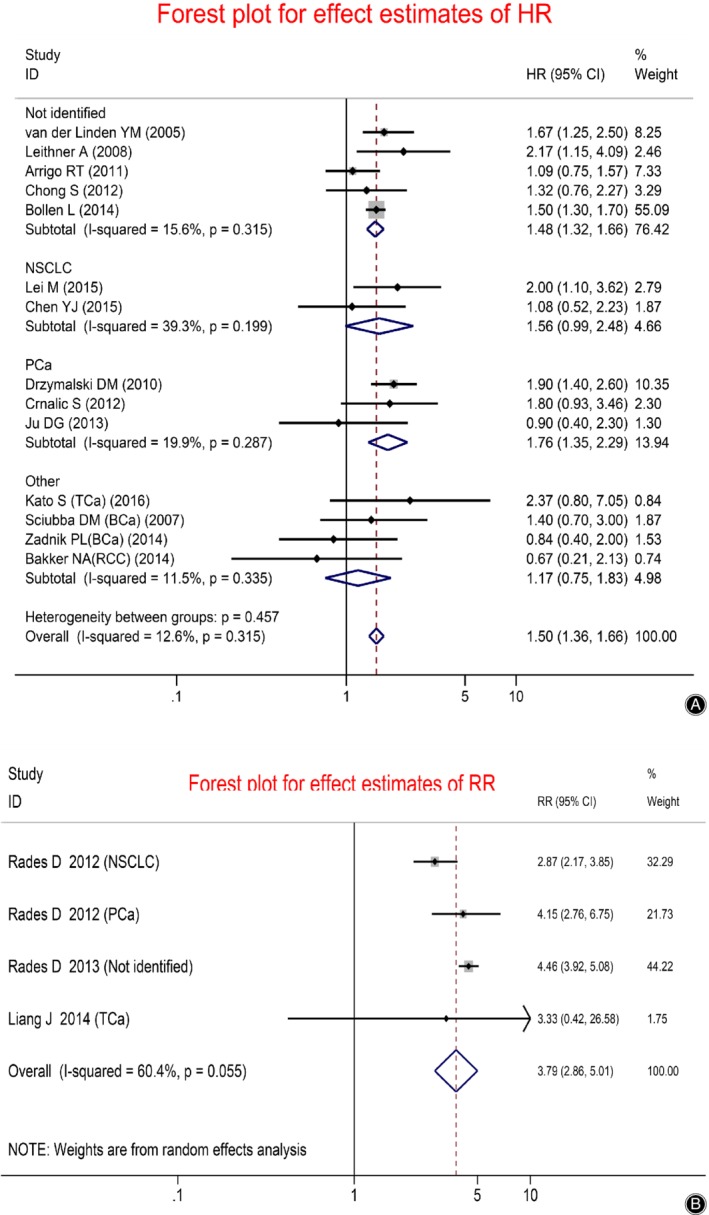

For the HR group (Fig. 1), all the effect estimates for HR were synthesized narratively by a subgroup meta‐analysis based on the primary tumor histology using the fixed‐effect model. The overall pooled effect size for HR was 1.50 (95% CI 1.36–1.66), which was substantiated as statistically significant. However, the subgroups of the thyroid, breast, and renal cancers did not achieve statistical significance (HR = 1.17, 95% CI 0.75–1.83, Z = 0.70, P = 0.486). In NSCLC subgroup, a marginal statistical significance was presented for the pooled HR (HR = 1.56, 95% CI 0.99–2.48, Z = 1.90, P = 0.058), whereas in the subgroup of prostate cancer, statistical significance was presented for the pooled HR (HR = 1.76, 95% CI 1.35–2.29).

For the RR group including three radiotherapy cohorts and one surgery cohort (Fig. 2), the effect estimates were pooled by the random‐effect meta‐analysis. The pooled effect size for RR was 3.79 (95% CI 2.86–5.01) and I 2 = 60.4%, which was proved to be significant by the Z‐test (Z = 9.33, P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Forest plot presenting the effect estimates of survival in patients with spinal metastases: (A) The effect sizes for HR between patients with and without visceral metastases; (B) The effect sizes for RR between patients with and without visceral metastases.

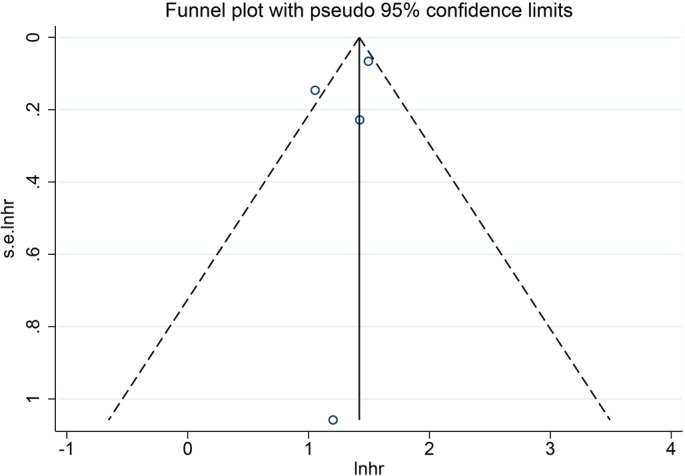

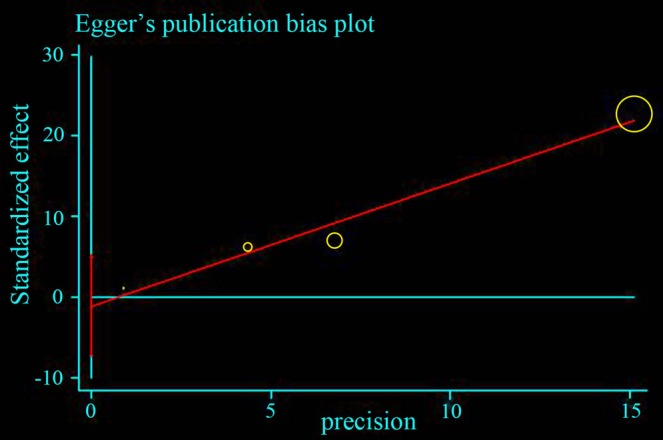

Publication Bias

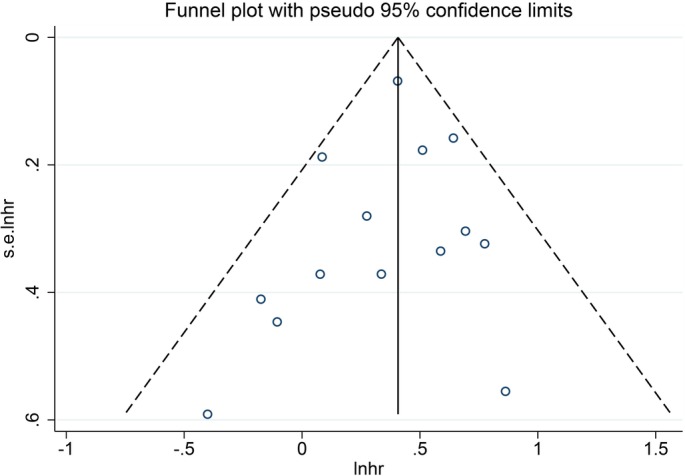

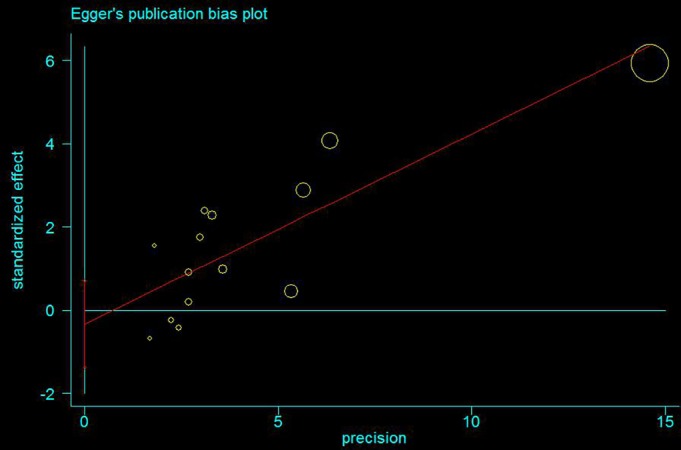

Funnel plot and Egger's test were performed to assess the publication bias (Figs 3, 4, 5, 6). The shape of the funnel plots did not reveal any evidence of obvious asymmetry in all the genetic models, and Egger's test provided statistical evidence. The results did not show any evidence of publication bias.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot presenting the publication conditions of 14 studies included in the forest plot A. A relative symmetry was presented visually.

Figure 4.

Egger's publication bias plot presenting the risk of bias across 14 studies involved in the forest plot A. The P‐value = 0.505 was considered statistically insignificant, and thus, the publication bias was not existent.

Figure 5.

Funnel plot presenting the publication conditions of four studies included in the forest plot B. A favorable symmetry was not presented visually, and thus, the publication bias might be present.

Figure 6.

Egger's publication bias plot presenting the risk of bias across four studies included in the forest plot B. The P‐value = 0.267 was considered non‐significant, and thus, the publication bias was not statistically significant.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first meta‐analysis for identifying the role of visceral metastasis in predicting the overall survival in patients with spinal metastases, providing useful information for physicians and surgeons. This study can clarify the current controversies in the field and render visceral metastasis as a remarkable prognostic factor for different pathological sub‐types. The study fully complied with a standard protocol, and all procedures were conducted by two physicians individually.

However, whether visceral metastasis is a prognostic factor for survival in patients with spinal metastases is controversial in current literature. Visceral metastasis was regarded as a major prognostic factor in various scoring systems13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 as it indicates aggressive tumor and shortens the life span of patients considerably. However, several studies21, 22 were opposed to the implementation of visceral metastasis as a significant prognostic factor based on their cohorts, which might be attributed to a greater degree of malignancy in spinal metastases than visceral metastases in specific tumors, such as lung cancer. Leithner et al.20 found that primary tumor and visceral metastases were the only significant parameters, according to multivariate analysis, in which all the seven parameters were assessed: general condition, extent of extraspinal bone metastases, extent of spinal metastases, visceral metastases, primary tumor, severity of spinal cord palsy, and pathological fracture. Tabouret et al.50 reported that multiple systemic metastases were not significantly predictive of survival, although a comparative analysis among the long‐term survivors and the other patients with overall survival <2 years exhibited significant differences. Arrigo et al.36 reported that visceral metastasis was not a significant predictor of mortality as evaluated from 200 surgically‐treated spinal metastasis patients. Chong et al.37 investigated preoperative prognostic factors of 108 patients, and the multivariate Cox proportional hazard model revealed that although the median survival of the patients with and without visceral metastases at the time of surgery was 4 and 11 months, respectively, it was not an independent prognostic factor. Lun et al.51 also determined that visceral metastases do not appear to predict the prognosis of patients with MSCC for some primary tumors. The current study focused on evidence‐based medicine, demonstrating that visceral metastasis is a statistically significant prognostic factor for overall survival after complete treatment, with pooled overall HR 1.50 (95% CI 1.36–1.66) as compared to patients with and without visceral metastasis.52

In the case of non‐small cell lung cancer, whether visceral metastasis affected the survival rate of patients, Lei et al.38 reported that visceral metastases significantly affected the survival as assessed by multivariate analysis, and Chen et al.39 reported a contradictory result, that visceral metastasis did not significantly associate with the survival in NSCLC patients with spinal metastases who underwent spinal surgery. In this study, the pooled effect estimate was 1.56 (95% CI 0.99–2.48) (Z = 1.90, P = 0.058), which showed that the relationship between visceral metastasis and survival prognosis was marginally significant. Because the effective valve of negative results would not be reported in the excluded studies,53 the prognostic impact of visceral metastases on survival is suspected; thus, further study is essential.

For patients with MSCC from prostate cancer, visceral metastasis did affect the survival rate of patients. Drzymalski et al.40 found that the presence of additional metastasis during the diagnosis of spinal metastasis was independently associated with a short overall survival. Crnalic et al.35 reported that visceral metastasis had a detrimental effect on the survival for prostate cancer, and found that the median survival in patients with visceral metastases was only 4 months as compared to 10 months in patients without visceral metastases. On the contrary, Ju et al.21 demonstrated that visceral metastases had no significant association with survival in patients with MSCC from prostate cancer. However, the pooled effect estimate was 1.76 (95% CI 1.35–2.29), which represented optimal correlations between visceral metastases and survival prognosis.

For patients with spinal metastases from thyroid cancer, no correlation was established between visceral metastasis and prognosis post‐surgery. Only two articles included in the meta‐analysis showed no statistical significance. Kato et al.41 reported that the presence of lung metastases was not associated with survival because lung metastases respond to radioiodine treatment as compared to the metastases of other organs. Sellin et al.27 reported visceral metastases did not affect patients' prognosis as assessed by multivariate analysis, although univariate analysis demonstrated a significant association with poor overall survival. Jiang et al.42 found that no significant effects on postoperative recurrence or survival were observed in the absence and presence of visceral metastasis.

According to the Tomita score, breast and kidney cancer were speculated to grow slowly and moderately, respectively. In the original and modified Baur score, the breast and kidney lesions could be compared to visceral metastasis and regarded as independent prognostic factors. However, Bakker et al.43 found that visceral metastasis was not associated significantly with survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Walcott et al.23 found that the concomitant presence of visceral lesions or multi‐focal bony disease did not exert a prognostic significance in patients with breast cancer. Although Han et al.54 demonstrated that visceral metastases significantly affected the patients' survival in univariate analysis, and the multivariate Cox regression model showed that it was not a prognostic factor in patients with renal cancer. In addition, Zadnik et al.22 examined the relationship of visceral metastases to survival in patients with MSCC from breast cancer and found that the median survival in the group with no visceral metastases was 25.9 months as compared to 28.1 months in the group with visceral metastases. The difference in the survival was not significant between groups as assessed by Mantel–Cox testing. In another study by Sciubba et al.44, the median survival of patients without visceral metastases was 28.0 months as compared to 17.4 months in the cases with visceral metastases. However, the result of multivariate analysis was similar to that by Zadnik et al.22 without a statistical difference. The current study showed that visceral metastasis was not a vital prognostic factor in breast and renal cancers, and the pooled effect estimate was only 1.11 (95% CI 0.65–1.91) and 0.67 (95% CI 0.21–2.13), respectively.

Limitations

Notably, our study has several limitations. First, some studies did not present an effect on the size in the multivariate analysis of overall survival; however, the Kaplan–Meier curves or survival rates at specific time points affected the estimate of HRs that was deduced from the raw data. Although these features exerted an inevitable bias on the actual results, it has become a widely accepted method when actual data is unavailable from primary literature as the estimates were similar to real results. Moreover, these data were indispensable as the reporting bias was subsistent; these studies did not present results that were insignificant in multivariate analysis and could be reflected as results obtained from raw data that were not statistically significant. Additionally, studies included in the meta‐analysis were high‐quality observational cohort designs. The absence of any randomized controlled trial (RCT) might be attributed to the few RCTs carried out to date. In addition, a majority of the studies were high‐quality according to NOS. Finally, only a few studies reported the prognostic effect of visceral metastasis in patients with spinal metastases from primary tumors such as renal cancer and breast cancer. However, we obtained valuable results from a meta‐analysis from the evidence‐based medical methods.

Conclusions

The current study suggested that the occurrence of visceral metastases has a strong negative impact on survival and should be considered while choosing a precision treatment. Interestingly, the onset of visceral metastases exhibited various impacts on survival in different primary tumors. However, visceral metastasis in thyroid cancer, breast cancer, and renal cancer cannot yet be confirmed as a significant prognostic factor for survival, thereby necessitating further studies. Thus, large prospective trials are required to better define the prognostic value of visceral metastasis in a patient with different tumors.

Grant Sources: This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not‐for‐profit sectors.

Disclosure: All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Byrne TN. Spinal cord compression from epidural metastases. N Engl J Med, 1992, 327: 614–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jacobs WB, Perrin RG. Evaluation and treatment of spinal metastases: an overview. Neurosurg Focus, 1992, 11: e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barron KD, Hirano A, Araki S, Terry RD. Experiences with metastatic neoplasms involving the spinal cord. Neurology, 1959, 9: 91–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sundaresan N, Digiacinto GV, Hughes JE, Cafferty M, Vallejo A. Treatment of neoplastic spinal cord compression: results of a prospective study. Neurosurgery, 1991, 29: 645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bell GR. Surgical treatment of spinal tumors. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1997, 335: 54–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bilsky MH, Lis E, Raizer J, Lee H, Boland P. The diagnosis and treatment of metastatic spinal tumor. Oncologist, 1999, 4: 459–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lun DX, Xu LN, Wang F, et al Prognostic differences in patients with solitary and multiple spinal metastases. Orthop Surg, 2019, 11: 443–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. York JE, Walsh GL, Lang FF, Putnam JB, McCutcheon IE, Swisher SG. Combined chest wall resection with vertebrectomy and spinal reconstruction for the treatment of Pancoast tumors. J Neurosurg, 1999, 91: 74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Patchell R, Tibbs PA, Regine WF. Direct decompressive surgical resection in the treatment of spinal cord compression caused by metastatic cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet, 2005, 366: 643–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Prasad D, Schiff D. Malignant spinal‐cord compression. Lancet Oncol, 2005, 6: 15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yang XG, Han Y, Wang F, et al Is ambulatory status a prognostic factor of survival in patients with spinal metastases? An exploratory meta‐analysis. Orthop Surg, 2018, 10: 173–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lun DX, Yang XG, Wang F, et al The establishment of a decision tree model for the individualized treatment of spinal metastases based on RPA. Chin J Orthop, 2018, 38: 881–888. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tomita K, Kawahara N, Kobayashi T, Yoshida A, Murakami H, Akamaru T. Surgical strategy for spinal metastases. Spine, 2001, 26: 298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tokuhashi Y, Matsuzaki H, Toriyama S, Kawano H, Ohsaka S. Scoring system for the preoperative evaluation of metastatic spine tumor prognosis. Spine, 1990, 15: 1110–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tokuhashi Y1, Matsuzaki H, Oda H, Oshima M, Ryu J. A revised scoring system for preoperative evaluation of metastatic spine tumor prognosis. Spine, 2005, 30: 2186–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sioutos PJ, Arbit E, Meshulam CF, Galicich JH. Spinal metastases from solid tumors. Analysis of factors affecting survival. Cancer, 1995, 76: 1453–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. North RB, LaRocca VR, Schwartz J, et al Surgical management of spinal metastases: analysis of prognostic factors during a 10‐year experience. J Neurosurg Spine, 2005, 2: 564–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Van der Linden YM, Dijkstra SP, Vonk EJ, Marijnen CA, Leer JW, Dutch Bone Metastasis Study Group . Prediction of survival in patients with metastases in the spinal column: results based on a randomized trial of radiotherapy. Cancer, 2005, 103: 320–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bauer HC, Wedin R. Survival after surgery for spinal and extremity metastases. Prognostication in 241 patients. Acta Orthop Scand, 1995, 66: 143–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Leithner A, Radl R, Gruber G, et al Predictive value of seven preoperative prognostic scoring systems for spinal metastases. Eur Spine J, 2008, 17: 1488–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ju DG, Zadnik PL, Groves ML, et al Factors associated with improved outcomes following decompressive surgery for prostate cancer metastatic to the spine. Neurosurgery, 2013, 73: 657–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zadnik PL, Hwang L, Ju DG, et al Prolonged survival following aggressive treatment for metastatic breast cancer in the spine. Clin Exp Metastasis, 2014, 31: 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Walcott BP, Cvetanovich GL, Barnard ZR, Nahed BV, Kahle KT, Curry WT. Surgical treatment and outcomes of metastatic breast cancer to the spine. J Clin Neurosci, 2011, 18: 1336–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time‐to‐event data into meta‐analysis. Trials, 2007, 8: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wells GA, Shea BJ, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non‐randomized studies in meta‐analysis. Appl Eng Agric, 2000, 18: 727–734. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 1997, 315: 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sellin JN, Suki D, Harsh V, et al Factors affecting survival in 43 consecutive patients after surgery for spinal metastases from thyroid carcinoma. J Neurosurg Spine, 2015, 23: 419–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rades D, Huttenlocher S, Bajrovic A, et al Surgery followed by radiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone for metastatic spinal cord compression from unfavorable tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2011, 81: e861–e868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rades D, Huttenlocher S, Evers JN, et al Do elderly patients benefit from surgery in addition to radiotherapy for treatment of metastatic spinal cord compression? Strahlenther Onkol, 2012, 188: 424–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rades D, Weber A, Karstens JH, Schild SE, Bartscht T. Number of extraspinal organs with metastases: a prognostic factor of survival in patients with metastatic spinal cord compression (MSCC) from non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Anticancer Res, 2014, 34: 2503–2507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rades D, Fehlauer F, Schulte R, et al Prognostic factors for local control and survival after radiotherapy of metastatic spinal cord compression. J Clin Oncol, 2006, 24: 3388–3393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lei M, Liu Y, Yan L, Tang C, Yang S, Liu S. A validated preoperative score predicting survival and functional outcome in lung cancer patients operated with posterior decompression and stabilization for metastatic spinal cord compression. Eur Spine J, 2016, 25: 3971–3978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lei M, Liu Y, Liu S, Wang L, Zhou S, Zhou J. Individual strategy for lung cancer patients with metastatic spinal cord compression. Eur J Surg Oncol, 2016, 42: 728–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Meng T, Chen R, Zhong N, et al Factors associated with improved survival following surgical treatment for metastatic prostate cancer in the spine: retrospective analysis of 29 patients in a single center. World J Surg Oncol, 2016, 14: 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Crnalic S, Hildingsson C, Wikström P, Bergh A, Löfvenberg R, Widmark A. Outcome after surgery for metastatic spinal cord compression in 54 patients with prostate cancer. Acta Orthop, 2012, 83: 80–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Arrigo RT, Kalanithi P, Cheng I, et al Predictors of survival after surgical treatment of spinal metastasis. Neurosurgery, 2011, 68: 674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chong S, Shin SH, Yoo H, et al Single‐stage posterior decompression and stabilization for metastasis of the thoracic spine: prognostic factors for functional outcome and patients' survival. Spine J, 2012, 12: 1083–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lei M, Liu Y, Tang C, Yang S, Liu S, Zhou S. Prediction of survival prognosis after surgery in patients with symptomatic metastatic spinal cord compression from non‐small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer, 2015, 15: 853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen YJ, Chen HT, Hsu HC. Preoperative palsy score has no significant association with survival in non‐small‐cell lung cancer patients with spinal metastases who undergo spinal surgery. J Orthop Surg Res, 2015, 10: 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Drzymalski DM, Oh WK, Werner L, Regan MM, Kantoff P, Tuli S. Predictors of survival in patients with prostate cancer and spinal metastasis. Presented at the 2009 Joint Spine Section Meeting. Clinical Article. J Neurosurg Spine, 2010, 13: 789–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kato S, Murakami H, Demura S, et al The impact of complete surgical resection of spinal metastases on the survival of patients with thyroid cancer. Cancer Med, 2014, 5: 2343–2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jiang L, Ouyang H, Liu X, et al Surgical treatment of 21 patients with spinal metastases of differentiated thyroid cancer. Chin Med J (Engl), 2014, 127: 4092–4096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bakker NA, Coppes MH, Vergeer RA, Kuijlen JM, Groen RJ. Surgery on spinal epidural metastases (SEM) in renal cell carcinoma: a plea for a new paradigm. Spine J, 2014, 14: 2038–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sciubba DM, Gokaslan ZL, Suk I, et al Positive and negative prognostic variables for patients undergoing spine surgery for metastatic breast disease. Eur Spine J, 2007, 16: 1659–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rades D, Hueppe M, Schild SE. A score to identify patients with metastatic spinal cord compression who may be candidates for best supportive care. Cancer, 2014, 119: 897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bollen L, van der Linden YM, Pondaag W, et al Prognostic factors associated with survival in patients with symptomatic spinal bone metastases: a retrospective cohort study of 1,043 patients. Neuro Oncol, 2014, 16: 991–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rades D, Douglas S, Veninga T, et al Metastatic spinal cord compression in non‐small cell lung cancer patients. Prognostic factors in a series of 356 patients. Strahlenther Onkol, 2012, 188: 472–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rades D, Douglas S, Veninga T, et al A survival score for patients with metastatic spinal cord compression from prostate cancer. Strahlenther Onkol, 2012, 188: 802–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Crnalic S, Löfvenberg R, Bergh A, Widmark A, Hildingsson C. Predicting survival for surgery of metastatic spinal cord compression in prostate cancer: a new score. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1992, 37: 2168–2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tabouret E, Gravis G, Cauvin C, Loundou A, Adetchessi T, Fuentes S. Long‐term survivors after surgical management of metastatic spinal cord compression. Eur Spine J, 2015, 24: 209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lun DX, Wang XD, Ji YD, et al Relationship between visceral metastases and survival in patients with metastasis‐related spinal cord compression. Orthop Surg, 2019, 11: 414–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Han S, Wang T, Jiang D, et al Surgery and survival outcomes of 30 patients with neurological deficit due to clear cell renal cell carcinoma spinal metastases. Eur Spine J, 2015, 24: 1786–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Park SJ, Lee CS, Chung SS. Surgical results of metastatic spinal cord compression (MSCC) from non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): analysis of functional outcome, survival time, and complication. Spine J, 2016, 16: 322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Han S, Wang T, Jiang D, et al Surgery and survival outcomes of 30 patients with neurological deficit due to clear cell renal cell carcinoma spinal metastases. Eur Spine J, 2015, 24: 1786–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]