Abstract

Introduction

Dynamic changes both in clinical profile and treatment strategy of non ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) patients have been observed recently. The exact impact of them on prognosis in a wide national population remains unclear.

Aim

To evaluate the impact of treatment advances between 2005 and 2014 on the outcomes of NSTEMI cases.

Material and methods

NSTEMI patients from the Polish Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes (PL-ACS) were included to the analysis. The mortality rate in a hospital observation as well as in 12-month follow-up was evaluated.

Results

The frequency of diabetes, hypertension, prior coronary artery interventions (especially percutaneous coronary intervention) raised. A frequency of invasive procedures increased remarkably (coronary angiography from 35.8% to 90.7%; p < 0.05 and percutaneous coronary intervention from 25.7% to 63.6%; p < 0.05). The usage of P2Y12 – inhibitors raised substantially from 56% to 93%; p < 0.05. In-hospital mortality decreased by fifty percent (in women from 6.6% to 3.3%; p < 0.001 and in men from 4.9% to 2.5%; p < 0.001, respectively). Similarly, 12-month mortality decreased up to one third (in women from 21.6% to 15.1%; p < 0.001 and in men from 17.8% to 12.8%; p < 0.001, respectively). Invasive strategy appeared to be the strongest factor decreasing mortality. Into in-hospital observation it reduces triple mortality risk whereas in 12-month follow up twice. Using propensity score matching analysis the impact of the treatment improvements on relative risk reduction was estimated on over 60%.

Conclusions

In last decade the outcomes of NSTEMI in Poland improved substantially. The predominant impact on it had a routine invasive strategy.

Keywords: outcomes, non ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, propensity score matching, invasive treatment

Summary

Dynamic changes both in clinical profile and treatment strategy of non ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) patients have been observed recently. The exact impact of them on prognosis in a wide national population remains unclear. NSTEMI patients from the Polish Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes (PL-ACS) were included to the analysis. In-hospital mortality decreased by fifty percent (in women from 6.6% to 3.3%; p < 0.001 and in men from 4.9% to 2.5%; p < 0.001, respectively). Similarly, 12-month mortality decreased up to one third (in women from 21.6% to 15.1%; p < 0.001 and in men from 17.8% to 12.8%; p < 0.001, respectively). Invasive strategy appeared to be the strongest factor decreasing mortality. Into in-hospital observation it reduces triple mortality risk whereas in 12-month follow up twice. Using propensity score matching analysis the impact of the treatment improvements on relative risk reduction was estimated on over 60%.

Introduction

In the last decade a non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) has become the most common MI type in Poland which is consistent with previous observations from the majority of Western European countries [1]. Simultaneously, dynamic changes in the clinical profile and the treatment strategy have been noticed, however their contribution to outcomes in a wide national population remains unclear [2–5].

Aim

Using the data from the Polish Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes (PL-ACS) we analyzed the trends in clinical characteristics, treatment strategy and outcomes in almost two hundred thousand NSTEMI cases registered between 2005 and 2014.

Material and methods

The study population was drawn from 463 hospitals in Poland providing care for patients with MI. It consists of patients admitted with a diagnosis of NSTEMI according to the guidelines of European Society of Cardiology (ESC) [6–8]. The study covers last 10-year period from 2005 to 2014. Contribution to the study was voluntary, nevertheless it comprises a half of all estimated cases of NSTEMI in Poland in that time. The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the PL-ACS Registry committee.

Data was collected from the PL-ACS Registry questionnaires that include variables on demographic factors (gender, age), risk factors (smoking, arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus and obesity), previous coronary incidences and procedures (MI, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), coronary artery by-pass grafting (CABG)), clinical presentation on admission (Killip class, heart rate, systolic blood pressure), electrocardiographic abnormalities (left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) – echocardiographic assessment on admission), coronary angiography (CA), coronary intervention details and in-hospital and post-discharge treatment. In-hospital complications (including bleeding, stroke and re-infarction (ST-elevation in at least two contiguous leads in association with ischemic symptoms)) as well as in-hospital mortality together with 12-month follow-up were evaluated. Propensity score matching (PSM) was used to compensate for the nonrandomized design of the study to control for imbalances in patients characteristics.

Statistical analysis

Females and males were analyzed separately. To assess age impact on outcomes the analysis was conducted in consecutive decades of life. Changes over time were investigated as comparison between subgroup in marginal 3-year intervals (2005–2007 and 2012–2014).

Categorical data are presented as numbers and percentages while continuous data as arithmetic mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences in categorical variables were tested by χ2 test with Pearson modification whereas in continuous variables with Student t-test. A two-sided p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. A logistic regression was used to identify variables that independently contributed to mortality. Propensity scores were calculated using a multiple regression model that included all covariates presented in Table I. Matching was performed using a nearest neighbor algorithm. In-hospital and 12-month mortality were evaluated of the studied groups as well as propensity score-matched subgroups were evaluated. Finally, the impact of the change in the treatment strategy changes was estimated by comparison the relative risk reduction (RRR) in the PSM groups with the RRR in the entire study group.

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of NSTEMI patients after propensity score matching

| Parameter | Women | Men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005–2007 | 2012–2014 | P-value | 2005–2007 | 2012–2014 | P-value | |

| 17346 (100%) | 17346 (100%) | 26059 (100%) | 26059 (100%) | |||

| Risk factors: | ||||||

| Hypertension | 13489 (77.8) | 13541 (78.1) | 0.501 | 18399 (70.6) | 18565 (71.2) | 0.109 |

| Diabetes | 6106 (35.2) | 6094 (35.1) | 0.893 | 6387 (24.5) | 6497 (24.9) | 0.264 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 7472 (43.1) | 7496 (43.2) | 0.795 | 11080 (42.5) | 11165 (42.8) | 0.452 |

| Smoking | 2015 (11.6) | 2102 (12.1) | 0.149 | 8098 (31.1) | 7997 (30.7) | 0.338 |

| Obesity | 4310 (24.8) | 4338 (25.0) | 0.729 | 4242 (16.3) | 4369 (16.8) | 0.134 |

| Prior MI | 3247 (18.7) | 3069 (17.7) | 0.013 | 5954 (22.8) | 5570 (22.1) | 0.054 |

| Prior PCI | 731 (4.2) | 876 (5.1) | < 0.001 | 1666 (6.4) | 1987 (7.6) | < 0.001 |

| Prior CABG | 693 (4.0) | 690 (4.0) | 0.934 | 1634 (6.3) | 1650 (6.3) | 0.773 |

| Clinical characteristics on admission: | ||||||

| SBP < 100 mm Hg | 651 (3.8) | 652 (3.8) | 0.448 | 892 (3.6) | 904 (3.5) | 0.406 |

| SBP 100–160 mm Hg | 12232 (74.4) | 12863 (75.0) | 0.234 | 19417 (79.1) | 20505 (79.3) | 0.566 |

| SBP > 160 mm Hg | 3559 (21.6) | 3645 (21.2) | 0.366 | 4247 (17.3) | 4455 (17.2) | 0.834 |

| HR > 100/min | 2162 (13.1) | 2113 (12.3) | 0.029 | 2747 (11.2) | 2779 (10.8) | 0.169 |

| Killip class 4 | 377 (2.2) | 344 (2.0) | 0.298 | 564 (2.2) | 519 (2.0) | 0.251 |

| Killip class 3 | 939 (5.4) | 834 (4.9) | 0.025 | 1083 (4.2) | 1008 (3.9) | 0.179 |

| Killip class 2 | 2826 (16.3) | 2602 (15.2) | 0.007 | 3477 (13.3) | 3305 (12.9) | 0.106 |

| ECG: sinus rythm | 14209 (86.1) | 14678 (85.8) | 0.427 | 21751 (88.2) | 22682 (88.1) | 0.904 |

| ECG: atrial fibrilation | 1690 (10.2) | 1659 (9.7) | 0.097 | 1950 (7.9) | 1963 (7.6) | 0.195 |

| ECG: pacemaker | 207 (1.3) | 213 (1.2) | 0.940 | 295 (1.2) | 285 (1.1) | 0.352 |

| ECG: ST-segment depression | 7704 (44.4) | 7675 (44.2) | 0.754 | 10542 (40.5) | 10675 (41.0) | 0.236 |

| ECG: T-wave inversion | 3409 (19.7) | 3384 (19.5) | 0.735 | 4877 (18.7) | 4836 (18.6) | 0.645 |

| ECG: other ST-T abnormal. | 5120 (29.5) | 5044 (29.1) | 0.370 | 8557 (32.8) | 8383 (32.2) | 0.104 |

| ECG: normal | 1623 (9.4) | 1285 (7.4) | < 0.001 | 2790 (10.7) | 2198 (8.4) | < 0.001 |

| LVEF > 50% | 4010 (44.0) | 6077 (43.9) | 0.968 | 5802 (39.1) | 8262 (38.9) | 0.749 |

| LVEF 35–50% | 4174 (45.8) | 6385 (46.2) | 0.550 | 7116 (47.9) | 10168 (47.9) | 0.940 |

| LVEF < 35% | 939 (10.3) | 1372 (9.9) | 0.355 | 1923 (13.0) | 2794 (13.2) | 0.566 |

| Time pain to admission 0–2 h | 1919 (13.1) | 1890 (12.4) | 0.071 | 3169 (14.3) | 3205 (13.9) | 0.190 |

| Time pain to admission 2–12 h | 7038 (48.2) | 7361 (48.4) | 0.652 | 10594 (47.9) | 11149 (48.3) | 0.339 |

| Time pain to admission > 12 h | 5650 (38.7) | 5944 (39.1) | 0.438 | 8376 (37.8) | 8728 (37.8) | 0.964 |

| Time pain to admission > 24 h | 3705 (25.4) | 3905 (25.7) | 0.508 | 5585 (25.20 | 5764 (25.0) | 0.531 |

| Prehospital cardiac arrest | 190 (1.1) | 164 (0.9) | 0.173 | 365 (1.4) | 335 (1.3) | 0.269 |

CABG – coronary artery by-pass graft, ECG – electrocardiogram, HR – heart rate, LVEF – left ventricle ejection fraction, MI – myocardial infarction, PCI – percutaneous coronary intervention, SBP – systolic blood pressure.

Results

A total of 197,192 patients (including 77,550 women, 39.3%) hospitalized in Poland due to NSTEMI between 2005 and 2014 were enrolled. All patients from two marginal 3-year periods (i.e. 2005–2007 and 2012–2014) were incorporated to the final analysis (Table II). Two matched cohorts of 17,346 women as well as two matched cohorts of 26,059 men were created as a result of the propensity score matching (Table I).

Table II.

Baseline characteristics of NSTEMI patients

| Parameter | Women | Men | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005–2007 | 2012–2014 | P-value | 2005–2007 | 2012–2014 | P-value | ||

| 23189 (100%) | 25542 (100%) | 33148 (100%) | 41125 (100%) | ||||

| Risk factors: | |||||||

| Hypertension | 17908 (77.2) | 20568 (80.5) | < 0.001 | 22792 (68.8) | 31219 (75.9) | < 0.001 | |

| Diabetes | 8180 (35.3) | 9623 (37.3) | < 0.001 | 7865 (23.7) | 11999 (29.2) | < 0.001 | |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 10182 (43.9) | 11264 (44.1) | 0.671 | 14446 (43.6) | 18067 (43.9) | 0.337 | |

| Smoking | 2403 (10.4) | 3340 (13.1) | < 0.001 | 10595 (32.0) | 10989 (26.7) | < 0.001 | |

| Obesity | 5879 (25.4) | 6391 (25.0) | 0.400 | 5143 (15.5) | 7807 (19.0) | < 0.001 | |

| Prior MI | 5899 (25.4) | 5681 (22.2) | < 0.001 | 10097 (30.5) | 10728 (26.1) | < 0.001 | |

| Prior PCI | 736 (3.2) | 4301 (16.8) | < 0.001 | 1680 (5.1) | 8534 (20.8) | < 0.001 | |

| Prior CABG | 1321 (5.7) | 1092 (4.3) | < 0.001 | 2764 (8.3) | 2755 (6.7) | < 0.001 | |

| Clinical characteristics on admission: | |||||||

| SBP < 100 mm Hg | 1034 (4.7) | 813 (3.4) | < 0.001 | 1407 (4.5) | 1201 (2.9) | < 0.001 | |

| SBP 100–160 mm Hg | 15744 (71.1) | 19698 (77.8) | < 0.001 | 24468 (77.8) | 33140 (81.1) | < 0.001 | |

| SBP > 160 mm Hg | 5367 (24.2) | 4795 (18.9) | < 0.001 | 5588 (17.8) | 6505 (15.9) | < 0.001 | |

| HR > 100/min | 3713 (16.7) | 2501 (9.9) | < 0.001 | 4402 (13.9) | 3470 (8.5) | < 0.001 | |

| Killip class 4 | 662 (2.9) | 388 (1.5) | < 0.001 | 919 (2.8) | 659 (1.6) | < 0.001 | |

| Killip class 3 | 1932 (8.3) | 995 (4.0) | < 0.001 | 2052 (6.2) | 1231 (3.0) | < 0.001 | |

| Killip class 2 | 4349 (18.8) | 3265 (13.0) | < 0.001 | 5109 (15.4) | 4462 (11.0) | < 0.001 | |

| ECG: sinus rythm | 18667 (83.6) | 22072 (87.6) | < 0.001 | 27506 (86.9) | 36102 (88.9) | < 0.001 | |

| ECG: atrial fibrilation | 2728 (12.2) | 2062 (8.2) | < 0.001 | 2764 (8.7) | 2822 (6.9) | < 0.001 | |

| ECG: pacemaker | 292 (1.3) | 293 (1.2) | 0.145 | 419 (1.3) | 472 (1.2) | 0.051 | |

| ECG: ST-segment depression | 11124 (48.8) | 10361 (40.6) | < 0.001 | 14564 (43.9) | 15200 (37.0) | < 0.001 | |

| ECG: T-wave inversion | 6778 (29.2) | 3795 (14.9) | < 0.001 | 8798 (26.5) | 5559 (13.5) | < 0.001 | |

| ECG: other ST-T abnormal. | 5957 (14.9) | 7725 (30.0) | < 0.001 | 9802 (21.1) | 13542 (32.8) | < 0.001 | |

| ECG: normal | 1648 (7.1) | 3703 (14.5) | < 0.001 | 2817 (8.5) | 6857 (16.7) | < 0.001 | |

| LVEF > 50% | 5077 (42.0) | 8890 (43.3) | 0.019 | 7015 (37.3) | 12851 (38.2) | 0.043 | |

| LVEF 35–50% | 5647 (46.7) | 9662 (47.1) | 0.505 | 9062 (48.2) | 16331 (48.6) | 0.437 | |

| LVEF < 35% | 1370 (11.3) | 1973 (9.6) | < 0.001 | 2706 (14.4) | 4421 (13.2) | < 0.001 | |

| Time pain to admission 0–2 h | 3322 (16.7) | 2247 (10.1) | < 0.001 | 4966 (17.5) | 4097 (11.3) | < 0.001 | |

| Time pain to admission 2–12 h | 9227 (46.7) | 10882 (48.7) | < 0.001 | 13123 (46.2) | 17726 (49.0) | < 0.001 | |

| Time pain to admission > 12 h | 7227 (36.5) | 9205 (41.2) | < 0.001 | 10342 (36.4) | 14374 (39.7) | < 0.001 | |

| Time pain to admission > 24 h | 4850 (24.5) | 5818 (26.0) | < 0.001 | 7115 (25.0) | 9157 (25.3) | < 0.001 | |

| Prehospital cardiac arrest | 360 (1.6) | 204 (0.8) | < 0.001 | 712 (2.1) | 389 (0.9) | < 0.001 | |

CABG – coronary artery by-pass graft, ECG – electrocardiogram, HR – heart rate, LVEF – left ventricle ejection fraction, MI – myocardial infarction, PCI – percutaneous coronary intervention, SBP – systolic blood pressure.

In the last decade the mean age of males increased from 65.8 ±11.8 to 66.7 ±11.3 years (p < 0.001), whereas the mean age of females slightly decreased from 72.3 ±10.8 to 72.1 ±11.0 years (p = 0.018). The frequency of major coronary artery disease risk factors like diabetes, arterial hypertension, obesity (in men only), smoking (in women only) increased. In the later years of the study the rate of prior PCI increased significantly. Additionally, there were substantial differences in Killip class, blood pressure, heart rate, ECG and echocardiography (Table II). Differences in the baseline clinical characteristics were equalized by the propensity score matching model (Table I).

During the last decade the frequency of invasive procedures increased remarkably in general population (coronary angiography from 35.8% to 90.7%; p < 0.05 and percutaneous coronary intervention from 25.7% to 63.6%; p < 0.05) as well as in PSM subgroups (Table III). In addition there were also modifications in medical treatment scheme. The usage of P2Y12 – inhibitors (especially clopidogrel) raised substantially from 56% in 2005–2007 to 93%; p < 0.05 in 2012–2014 (Table III).

Table III.

Management of NSTEMI patients (after propensity score matching)

| Parameter | Women | Men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005–2007 | 2012–2014 | P-value | 2005–2007 | 2012–2014 | P-value | |

| 17346 (100%) | 17346 (100%) | 26059 (100%) | 26059 (100%) | |||

| Treatment strategy: | ||||||

| Hospitalisation on cardiology depart. | 12000 (69.2) | 15420 (88.9) | < 0.001 | 19222 (73.8) | 23982 (92.0) | < 0.001 |

| Conservative treatment | 11787 (68.0) | 2255 (13.0) | < 0.001 | 15032 (57.7) | 2315 (8.9) | < 0.001 |

| Coronary angiography | 5542 (32.0) | 15090 (87.0) | < 0.001 | 10998 (42.3) | 23744 (91.1) | < 0.001 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 3838 (22.1) | 10021 (57.8) | < 0.001 | 8015 (30.8) | 16861 (64.7) | < 0.001 |

| Second PCI (non-IRA) during indx hosp. | 612 (3.6) | 2268 (13.1) | < 0.001 | 1149 (4.4) | 2849 (10.9) | < 0.001 |

| PCI with stent implantation | 3357 (87.5) | 9083 (90.5) | < 0.001 | 7719 (88.9) | 15434 (91.3) | < 0.001 |

| PCI with BMS implantation | 3192 (83.2) | 4115 (41.0) | < 0.001 | 6808 (85.0) | 6618 (39.1) | < 0.001 |

| PCI with DES implantation | 165 (4.3) | 4968 (49.5) | < 0.001 | 311 (3.9) | 8816 (52.2) | < 0.001 |

| Intra aortic ballon pump | 52 (0.3) | 88 (0.5) | 0.023 | 105 (0.4) | 143 (0.5) | 0.016 |

| Medical treatment during hospitalisation: | ||||||

| Acetlosalycic acid | 15974 (92.1) | 14271 (82.3) | < 0.001 | 24244 (93.0) | 21671 (83.2) | < 0.001 |

| P2Y12B inhibitor | 9041 (52.1) | 16096 (92.8) | < 0.001 | 15581 (59.8) | 24281 (93.2) | < 0.001 |

| Clopidogrel | 7019 (40.5) | 16040 (92.5) | < 0.001 | 12625 (48.4) | 24243 (93.0) | < 0.001 |

| GPIIb/IIIa inhibitor | 371 (2.1) | 1318 (7.6) | < 0.001 | 880 (3.4) | 2619 (10.1) | < 0.001 |

| Heparin | 12949 (74.7) | 8919 (51.5) | < 0.001 | 18988 (72.9) | 13152 (50.5) | < 0.001 |

| Beta-adrenolytic | 13705 (79.0) | 11607 (66.9) | < 0.001 | 20499 (78.7) | 17790 (68.3) | < 0.001 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 1664 (9.8) | 2228 (12.8) | < 0.001 | 2032 (7.8) | 2878 (11.0) | < 0.001 |

| Statin | 13633 (78.6) | 12311 (71.0) | < 0.001 | 21050 (80.8) | 19224 (73.8) | < 0.001 |

| ACEI/ARB | 13616 (78.8) | 10529 (60.7) | < 0.001 | 20166 (77.4) | 16286 (62.6) | < 0.001 |

| Nitrate | 9366 (54.0) | 2496 (14.4) | < 0.001 | 13015 (49.9) | 3448 (13.2) | < 0.001 |

| Diuretics | 6903 (39.8) | 5100 (29.4) | < 0.001 | 8082 (31.0) | 6326 (24.3) | < 0.001 |

ACEI/ARB – angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker, BMS – bare metal stent, DES – drug eluting stent, IRA – infarct-related artery.

In that time the risk of in-hospital complications (re-infarction, stroke and cardiovascular death) decreased considerably. On the contrary, the risk of major bleeding incidences was higher in the later years of the study (Table IV). In the whole population in-hospital mortality decreased by fifty percent (from 5.6% in 2005–2007 to 2.8% in 2012–2014; p < 0.001, in women from 6.6% to 3.3%; p < 0.001 and in men from 4.9% to 2.5%; p < 0.001, respectively). Similarly, there was more than 30% decrease in the 12-month mortality (from 19.4% in 2005–2007 to 13.7% in 2012–2014; p < 0.001, in women from 21.6% to 15.1%; p < 0.001 and in men from 17.8% to 12.8%; p < 0.001, respectively). Also in the PSM model the outcomes improved considerably – in hospital mortality rates decreased by thirty percent whereas 12-month mortality decreased by 18% (Table IV).

Table IV.

Outcomes of NSTEMI patients (after propensity score matching)

| Parameter | Women | Men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005–2007 | 2012–2014 | P-value | 2005–2007 | 2012–2014 | P-value | |

| 17346 (100%) | 17346 (100%) | 26059 (100%) | 26059 (100%) | |||

| Myocardial reinfarction | 812 (4.7) | 59 (0.3) | < 0.001 | 1100 (4.3) | 82 (0.3) | < 0.001 |

| Stroke | 101 (0.6) | 54 (0.3) | < 0.001 | 78 (0.3) | 44 (0.2) | < 0.001 |

| Bleeding | 145 (0.8) | 270 (1.6) | < 0.001 | 137 (0.5) | 270 (1.0) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiovascular mortality in hospital | 964 (5.6) | 630 (3.6) | < 0.001 | 1051 (4.0) | 717 (2.8) | < 0.001 |

| Other cause of mortality in hospital | 54 (0.3) | 49 (0.3) | 0.622 | 68 (0.3) | 66 (0.3) | 0.863 |

| In-hospital mortality | 1018 (5.9) | 679 (3.9) | < 0.001 | 1119 (4.3) | 783 (3.0) | < 0.001 |

| 30-day mortality | 1535 (8.8) | 1303 (7.5) | < 0.001 | 1825 (7.0) | 1534 (5.9) | < 0.001 |

| 6-month mortality | 2760 (15.9) | 2204 (12.7) | < 0.001 | 3322 (12.7) | 2749 (10.6) | < 0.001 |

| 12-month mortality | 3474 (20.0) | 2812 (16.2) | < 0.001 | 4293 (16.5) | 3544 (13.6) | < 0.001 |

In the multivariable analysis the invasive strategy appeared to be the strongest factor decreasing mortality. It tripled the in-hospital and doubled the 12-month mortality rate reduction (Table V).

Table V.

Multivariate analysis of factors of in-hospital as well as 12-month mortality.

| Parameter | In-hospital mortality | 12-month mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Gender – female (vs. male) | 1.02 (0.97–1.08) | 0.4485 | 0.94 (0.92–0.97) | < 0.0001 |

| Age (on each decade) | 1.63 (1.59–1.68) | < 0.0001 | 1.57 (1.55–1.59) | < 0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 0.73 (0.69–0.78) | < 0.0001 | 0.85 (0.83–0.88) | < 0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 1.09 (1.03–1.15) | 0.0021 | 1.29 (1.26–1.32) | < 0.0001 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 0.73 (0.69–0.77) | < 0.0001 | 0.81 (0.79–0.83) | < 0.0001 |

| Smoking | 1.02 (0.94–1.10) | 0.6776 | 1.06 (1.03–1.10) | 0.0005 |

| Obesity | 1.18 (1.10–1.26) | < 0.0001 | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.37 |

| Previuos MI | 1.07 (1.01–1.14) | 0.0255 | 1.12 (1.09–1.15) | < 0.0001 |

| Previous PCI | 0.80 (0.73–0.88) | < 0.0001 | 0.90 (0.87–0.94) | < 0.0001 |

| Previous CABG | 0.80 (0.71–0.91) | 0.0006 | 0.84 (0.80–0.88) | < 0.0001 |

| SBP < 100 mm Hg | 2.25 (2.08–2.45) | < 0.0001 | 1.69 (1.62–1.77) | < 0.0001 |

| SBP > 160 mm Hg | 0.48 (0.43–0.52) | < 0.0001 | 0.68 (0.66–0.71) | < 0.0001 |

| HR > 100 /min | 1.31 (1.23–1.40) | < 0.0001 | 1.23 (1.19–1.27) | < 0.0001 |

| Killip 3 class | 3.67 (3.41–3.94) | < 0.0001 | 1.98 (1.91–2.06) | < 0.0001 |

| Killip 4 class | 13.2 (12.0–14.4) | < 0.0001 | 4.48 (4.26–4.71) | < 0.0001 |

| Other than sinus rythm on ECG | 1.19 (1.12–1.27) | < 0.0001 | 1.14 (1.11–1.18) | < 0.0001 |

| ST-T abnormalities on ECG | 1.16 (1.07–1.27) | 0.0007 | 1.15 (1.11–1.19) | < 0.0001 |

| LVEF 35–50% | 1.10 (1.01–1.20) | 0.0240 | 1.52 (1.47–1.57) | < 0.0001 |

| LVEF < 35% | 2.31 (2.11–2.53) | < 0.0001 | 2.67 (2.57–2.78) | < 0.0001 |

| Time to admission > 12 h | 1.09 (1.03–1.16) | 0.0030 | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | 0.022 |

| Prehospital cardiac arrest | 2.37 (2.09–2.69) | < 0.0001 | 1.74 (1.63–1.85) | < 0.0001 |

| Invasive treatment | 0.31 (0.29–0.33) | < 0.0001 | 0.51 (0.49–0.52) | < 0.0001 |

CABG – coronary artery by-pass graft, ECG – electrocardiogram, HR – heart rate, LVEF – left ventricle ejection fraction, MI – myocardial infarction, PCI – percutaneous coronary intervention, SBP – systolic blood pressure.

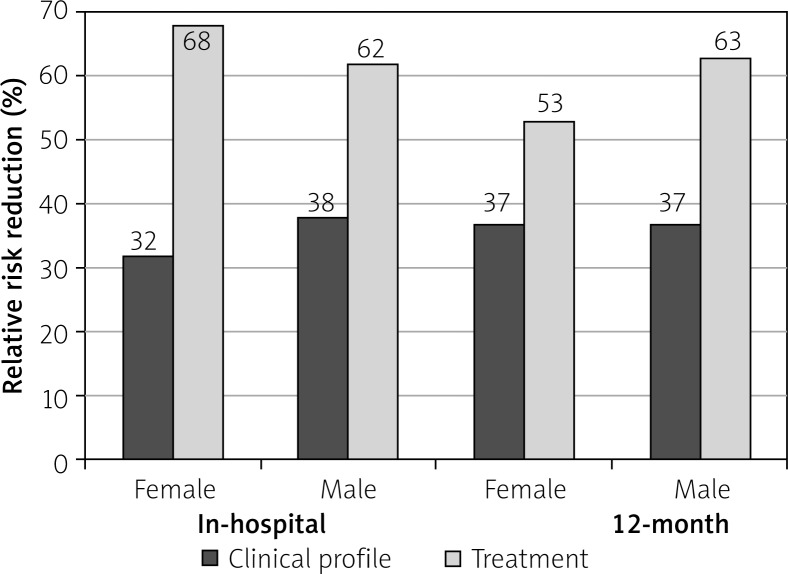

An estimated impact of the treatment improvements on relative risk reduction in in-hospital mortality amounted to 67.8% in women and 61.6% in men, respectively. Similarly changes of the management in the last decade accounted for 63.3% (in women) and 62.6% (in men) of the relative risk reduction in 12-month mortality (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Impact of the treatment improvements and clinical profile changes on mortality reduction in NSTEMI in 2005–2014

Discussion

The major finding of our study is the confirmation of the progress in therapeutic strategies to outcomes of the management of patients with NSTEMI in the last decade. The propensity score analysis revealed the substantial input (over 60%) of modern treatment into the overall benefit of prognosis. Irrespective of the clinical profile changes the routine invasive approach as well as modern medical therapies resulted in a spectacular mortality rates reduction.

As in many previous reports significant changes in the clinical characteristics, management and treatment outcomes of NSTEMI patients were observed [3–5]. The prevalence of major coronary risk factors like diabetes, obesity, arterial hypertension and chronic kidney disease is still increasing. On the contrary, percentage of smoking habit significantly decreased recently. Additionally, in the years 2005–2014 numerous changes in the clinical profile (mean age, gender, comorbidities and Killip class on admission) that might have impact on prognosis were noted [9–13].

Recently, a significant progress in the medical therapy was achieved, as the vast majority of NSTEMI patients receive double antiplatelet therapy (including P2Y12-receptor blockers). Previously, a significant proportion of patients were administered ticlopidine that was gradually substituted by clopidogrel and later by ticagrelor according to the guidelines of European Society of Cardiology [6–8]. Nevertheless, due to financial issue, the implantation of the novel antiplatelets agents in a routine practice was delayed in Poland compared with other countries.

An invasive approach became a predominant treatment strategy in NSTEMI [7, 8, 14, 15]. Importantly, the CA or PCI rates in Poland are currently equal to those in the Western Europe and United States [3, 4, 5, 16]. A rapid growth in invasive strategy utilization in Poland was distinctively noticeable in 2005–2011 that was mainly related to the opening of new catheterization laboratories. These allowed to follow ECS guidelines of that time on management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation from 2002 [6] and 2007 [7].

Multivariable analysis confirmed the significant invasive strategy contribution to outcomes which appear to be continuously better than previously reported [4, 9, 15].

In the last decade a spectacular decrease in mortality rates was observed in Poland which is in line with the reports from France, Sweden, Denmark and Germany [3, 5, 17, 18]. In contrast to the numerous other retrospective studies we applied the propensity score matching method to our analysis. By virtue of PSM the independent impact of the treatment development on outcomes was revealed. Interestingly, that input in prognosis improvements seems to be higher than it could be expected before.

Our study have several limitations. PL-ACS is a voluntary, observational study, and not all hospitals participated in the data collecting. Our analysis has a retrospective nature and some potentially important parameters might not be included. That is a single country study, therefore some trends should be interpreted with caution. Finally, propensity score matching analysis is based on a simplified model, even after data adjustment, the results could be biased by potentially important parameters that were not included.

Conclusions

In Poland, the routine invasive strategy implementation contributed substantially to the outcomes of NSTEMI patients in the last 10 years. The impact of treatment advances on better prognosis was estimated at over sixty percent.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gierlotka M, Zdrojewski T, Wojtyniak B, et al. Incidence, treatment, in-hospital mortality and one-year outcomes of acute myocardial infarction in Poland in 2009-2012 – nationwide AMI-PL database. Kardiol Pol. 2015;73:142–58. doi: 10.5603/KP.a2014.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gierlotka M, Gąsior M, Wilczek K, et al. Temporal trends in the treatment and outcomes of patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in Poland from 2004-2010 (from the Polish Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes) Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:779–86. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puymirat E, Simon T, Cayla G, et al. Acute myocardial infarction: changes in patient characteristics, management, and 6-month outcomes over a period of 20 years in the FAST-MI Program (French Registry of Acute ST-Elevation or Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) 1995 to 2015. Circulation. 2017;136:1908–19. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khera S, Kolte D, Aronow WS, et al. Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the United States: contemporary trends in incidence, utilization of the early invasive strategy, and in-hospital outcomes. Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000995. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mårtensson S, Gyrd-Hansen D, Prescott E, et al. Trends in time to invasive examination and treatment from 2001 to 2009 in patients admitted first time with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction or unstable angina in Denmark. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004052. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertrand ME, Simoons ML, Fox KA, et al. Management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Task Force on the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:1809–40. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2002.3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bassand JP, Hamm CW, Ardissino D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Task force for diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes of European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1598–660. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2999–3054. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gierlotka M, Gąsior M, Tajstra M, et al. Outcomes of invasive treatment in very elderly Polish patients with non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction from 2003-2009 (from the PL-ACS registry) Cardiol J. 2013;20:34–43. doi: 10.5603/CJ.2013.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Udell JA, Koh M, Qiu F, et al. Outcomes of women and men with acute coronary syndrome treated with and without percutaneous coronary revascularization. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e004319. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dégano IR, Subirana I, Fusco D, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention reduces mortality in myocardial infarction patients with comorbidities: implications for elderly patients with diabetes or kidney disease. Int J Cardiol. 2017;249:83–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatia S, Arora S, Bhatia SM, et al. Non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction among patients with chronic kidney disease: a propensity score-matched comparison of percutaneous coronary intervention versus conservative management. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e007920. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Subahi A, Abdullah A, Yassin AS, et al. Impact and outcomes of patients with congestive heart failure complicating non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, results from a nationally-representative United States cohort. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2019;20:659–62. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2018.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siudak Z, Ochała A, Lesiak M, et al. Temporal trends and patterns in percutaneous treatment of coronary artery disease in Poland in the years 2005-2011. Kardiol Pol. 2015;73:485–92. doi: 10.5603/KP.a2015.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puymirat E, Taldir G, Aissaoui N, et al. Use of invasive strategy in non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction is a major determinant of improved long-term survival: FAST-MI (French Registry of Acute Coronary Syndrome) JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:893–902. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darling CE, Fisher KA, McManus DD, et al. Survival after hospital discharge for ST-segment elevation and non-ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction: a population-based study. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5:229–36. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S45646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alfredsson J, Lindbäck J, Wallentin L, et al. Similar outcome with an invasive strategy in men and women with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: from the Swedish Web-System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART) Eur Heart J. 2011;32:31. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleopatra K, Muth K, Zahn R, et al. Effect of an invasive strategy on in-hospital outcome and one-year mortality in women with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2011;153:291–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]