Abstract

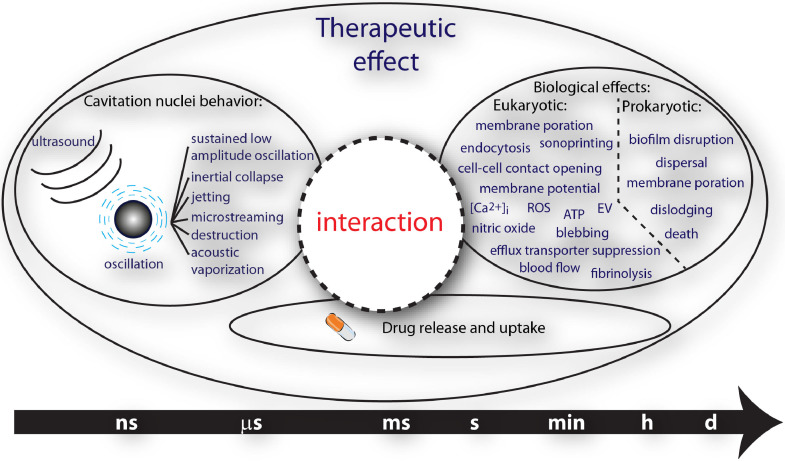

Therapeutic ultrasound strategies that harness the mechanical activity of cavitation nuclei for beneficial tissue bio-effects are actively under development. The mechanical oscillations of circulating microbubbles, the most widely investigated cavitation nuclei, which may also encapsulate or shield a therapeutic agent in the bloodstream, trigger and promote localized uptake. Oscillating microbubbles can create stresses either on nearby tissue or in surrounding fluid to enhance drug penetration and efficacy in the brain, spinal cord, vasculature, immune system, biofilm or tumors. This review summarizes recent investigations that have elucidated interactions of ultrasound and cavitation nuclei with cells, the treatment of tumors, immunotherapy, the blood–brain and blood–spinal cord barriers, sonothrombolysis, cardiovascular drug delivery and sonobactericide. In particular, an overview of salient ultrasound features, drug delivery vehicles, therapeutic transport routes and pre-clinical and clinical studies is provided. Successful implementation of ultrasound and cavitation nuclei-mediated drug delivery has the potential to change the way drugs are administered systemically, resulting in more effective therapeutics and less-invasive treatments.

Key Words: Ultrasound, Cavitation nuclei, Therapy, Drug delivery, Bubble–cell interaction, Sonoporation, Sonothrombolysis, Blood–brain barrier opening, Sonobactericide, Tumor

Introduction

Around the start of the European Symposium on Ultrasound Contrast Agents, ultrasound-responsive cavitation nuclei were reported to have therapeutic potential. Thrombolysis was reported to be accelerated in vitro (Tachibana and Tachibana 1995), and cultured cells were transfected with plasmid DNA (Bao et al. 1997). Since then, many research groups have investigated the use of cavitation nuclei for multiple forms of therapy, including tissue ablation and drug and gene delivery. In the early years, the most widely investigated cavitation nuclei were gas microbubbles, ∼1–10 µm in diameter and coated with a stabilizing shell, whereas today both solid and liquid nuclei, which can be as small as a few hundred nanometers, are also being investigated. Drugs can be co-administered with the cavitation nuclei or loaded in or on them (Lentacker et al. 2009; Kooiman et al. 2014). The diseases that can be treated with ultrasound-responsive cavitation nuclei include but are not limited to cardiovascular disease and cancer (Sutton et al. 2013; Paefgen et al. 2015), the current leading causes of death worldwide according to the World Health Organization (Nowbar et al. 2019). This review focuses on the latest insights into cavitation nuclei for therapy and drug delivery from the physical and biological mechanisms of bubble–cell interaction to pre-clinical (both in vitro and in vivo) and clinical (time span: 2014-2019) studies, with particular emphasis on the key clinical applications. The applications covered in this review are the treatment of tumors, immunotherapy, blood–brain barrier (BBB) and blood–spinal cord barrier, dissolution of clots, cardiovascular drug delivery and treatment of bacterial infections.

Cavitation nuclei for therapy

The most widely used cavitation nuclei are phospholipid-coated microbubbles with a gas core. For the 128 pre-clinical studies included in the treatment sections of this review, the commercially available and clinically approved Definity (Luminity in Europe; octafluoropropane gas core, phospholipid coating) (Definity 2011; Nolsøe and Lorentzen 2016) microbubbles were the most frequently used (in 22 studies). Definity was used for studies on all applications discussed here, mostly for opening the BBB (12 studies). SonoVue (Lumason in the United States) is commercially available and clinically approved as well (sulfur hexafluoride gas core, phospholipid coating) (Lumason 2016; Nolsøe and Lorentzen 2016) and was used in a total of 14 studies for treatment of non-brain tumors (e.g., Xing et al. 2016), BBB opening (e.g., Goutal et al. 2018) and sonobactericide (e.g., Hu et al. 2018). Other commercially available microbubbles were used that are not clinically approved, such as BR38 (Schneider et al. 2011) in the study by Wang et al. (2015d) and MicroMarker (VisualSonics) in the study by Theek et al. (2016). Custom-made microbubbles are as diverse as their applications, with special characteristics tailored to enhance different therapeutic strategies. Different types of gasses were used as the core such as air (e.g., Eggen et al. 2014), nitrogen (e.g., Dixon et al. 2019), oxygen (e.g., Fix et al. 2018), octafluoropropane (e.g., Pandit et al. 2019), perfluorobutane (e.g., Dewitte et al. 2015), sulfur hexafluoride (Bae et al. 2016; Horsley et al. 2019) or a mixture of gases such as nitric oxide and octafluoropropane (Sutton et al. 2014) or sulfur hexafluoride and oxygen (McEwan et al. 2015). While fluorinated gases improve the stability of phospholipid-coated microbubbles (Rossi et al. 2011), other gases can be loaded for therapeutic applications, such as oxygen for treatment of tumors (McEwan et al. 2015; Fix et al. 2018; Nesbitt et al. 2018) and nitric oxide (Kim et al. 2014; Sutton et al. 2014) and hydrogen gas (He et al. 2017) for treatment of cardiovascular disease. The main phospholipid component of custom-made microbubbles is usually a phosphatidylcholine such as 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), used in 13 studies (e.g., Dewitte et al. 2015; Bae et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2016; Fu et al. 2019), or 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC), used in 18 studies (e.g., Kilroy et al. 2014; Bioley et al. 2015; Dong et al. 2017; Goyal et al. 2017; Pandit et al. 2019). These phospholipids are popular because they are also the main components in Definity (Definity 2011) and SonoVue/Lumason (Lumason 2016), respectively. Another key component of the microbubble coating is a polyethylene glycol (PEG)ylated emulsifier such as polyoxyethylene (40) stearate (PEG40-stearate; e.g., Kilroy et al. 2014) or the most frequently used 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-carboxy(polyethylene glycol) (DSPE–PEG2000; e.g., Belcik et al. 2017), which is added to inhibit coalescence and to increase the in vivo half-life (Ferrara et al. 2009). In general, two methods are used to produce custom-made microbubbles: mechanical agitation (e.g., Ho et al. 2018) and probe sonication (e.g., Belcik et al. 2015). Both methods produce a population of microbubbles that is polydisperse in size. Monodispersed microbubbles produced by microfluidics have recently been developed, and are starting to gain attention for pre-clinical therapeutic studies. Dixon et al. (2019) used monodisperse microbubbles to treat ischemic stroke.

Various therapeutic applications have inspired the development of novel cavitation nuclei, which is discussed in depth in the companion review by Stride et al. (2020). To improve drug delivery, therapeutics can be either co-administered with or loaded onto the microbubbles. One strategy for loading is to create microbubbles stabilized by drug-containing polymeric nanoparticles around a gas core (Snipstad et al. 2017). Another strategy is to attach therapeutic molecules or liposomes to the outside of microbubbles, for example, by biotin–avidin coupling (Dewitte et al. 2015; McEwan et al. 2016; Nesbitt et al. 2018). Echogenic liposomes can be loaded with different therapeutics or gases and have been studied for vascular drug delivery (Sutton et al. 2014), treatment of tumors (Choi et al. 2014) and sonothrombolysis (Shekhar et al. 2017). Acoustic Cluster Therapy (ACT) combines Sonazoid microbubbles with droplets that can be loaded with therapeutics for treatment of tumors (Kotopoulis et al. 2017). The cationic microbubbles utilized in the treatment sections of this review were used mostly for vascular drug delivery, with genetic material loaded on the microbubble surface by charge coupling (e.g., Cao et al. 2015). Besides phospholipids and nanoparticles, microbubbles can also be coated with denatured proteins such as albumin. Optison (Optison 2012) is a commercially available and clinically approved ultrasound contrast agent that is coated with human albumin and used in studies on treatment of non-brain tumors (Xiao et al. 2019), BBB opening (Kovacs et al. 2017b; Payne et al. 2017) and immunotherapy (Sta Maria et al. 2015). Nano-sized particles cited in this review have been used as cavitation nuclei for treatment of tumors, such as nanodroplets (e.g., Cao et al. 2018) and nanocups (Myers et al. 2016); for BBB opening (nanodroplets; Wu et al. 2018); and for sonobactericide (nanodroplets; Guo et al. 2017a).

Bubble–cell interaction

Physics

The physics of the interaction between bubbles or droplets and cells are described as these are the main cavitation nuclei used for drug delivery and therapy.

Physics of microbubble–cell interaction

Being filled with gas and/or vapor makes bubbles highly responsive to changes in pressure, and hence, exposure to ultrasound can cause rapid and dramatic changes in their volume. These volume changes in turn give rise to an array of mechanical, thermal and chemical phenomena that can significantly influence the bubbles’ immediate environment and mediate therapeutic effects. For the sake of simplicity, these phenomena are discussed in the context of a single bubble. It is important to note, however, that biological effects are typically produced by a population of bubbles and the influence of inter-bubble interactions should not be neglected.

Mechanical effects

A bubble in a liquid is subject to multiple competing influences: the driving pressure of the imposed ultrasound field; the hydrostatic pressure imposed by the surrounding liquid; the pressure of the gas and/or vapor inside the bubble; surface tension and the influence of any coating material; the inertia of the surrounding fluid; and damping caused by the viscosity of the surrounding fluid and/or coating, thermal conduction and/or acoustic radiation.

The motion of the bubble is determined primarily by the competition between the liquid inertia and the internal gas pressure. This competition can be characterized by using the Rayleigh–Plesset equation for bubble dynamics to compare the relative contributions of the terms describing inertia and pressure to the acceleration of the bubble wall (Flynn 1975a):

| (1) |

where R is the time-dependent bubble radius with initial value Ro, pG is the pressure of the gas inside the bubble, p∞ is the combined hydrostatic and time-varying pressure in the liquid, σ is the surface tension at the gas–liquid interface, ρL is the liquid density, IF is inertia factor and PF the pressure factor.

Flynn (1975a, 1975b) identified two scenarios: If the PF is dominant when the bubble approaches its minimum size, then the bubble will undergo sustained volume oscillations. If the inertia term is dominant (IF), then the bubble will undergo inertial collapse, similar to an empty cavity, after which it may rebound or it may disintegrate. Which of these scenarios occurs is dependent upon the bubble expansion ratio Rmax/Ro and, hence, the bubble size and the amplitude and frequency of the applied ultrasound field.

Both inertial and non-inertial bubble oscillations can give rise to multiple phenomena that affect the bubble's immediate environment and hence are important for therapy. These include:

-

1.

Direct impingement: Even at moderate amplitudes of oscillation, the acceleration of the bubble wall may be sufficient to impose significant forces on nearby surfaces, easily deforming fragile structures such as biological cell membranes (van Wamel et al. 2006; Kudo 2017) and blood vessel walls (Chen et al. 2011).

-

2.

Ballistic motion: In addition to oscillating, the bubble may undergo translation as a result of the pressure gradient in the fluid generated by a propagating ultrasound wave (primary radiation force). Because of their high compressibility, bubbles may travel at significant velocities, sufficient to push them toward targets for improved local deposition of a drug (Dayton et al. 1999) or to penetrate biological tissue (Caskey et al. 2009; Bader et al. 2015; Acconcia et al. 2016).

-

3.

Microstreaming: When a structure oscillates in a viscous fluid there will be a transfer of momentum as a result of interfacial friction. Any asymmetry in the oscillation will result in a net motion of that fluid in the immediate vicinity of the structure known as microstreaming (Kolb and Nyborg 1956). This motion will in turn impose shear stresses upon any nearby surfaces, as well as increase convection within the fluid. Because of the inherently non-linear nature of bubble oscillations (eqn [1]), both non-inertial and inertial cavitation can produce significant microstreaming, resulting in fluid velocities on the order of 1 mm/s (Pereno and Stride 2018). If the bubble is close to a surface then it will also exhibit non-spherical oscillations, which increases the asymmetry and hence the microstreaming even further (Nyborg 1958; Marmottant and Hilgenfeldt 2003).

-

4.

Microjetting: Another phenomenon associated with non-spherical bubble oscillations near a surface is the generation of a liquid jet during bubble collapse. If there is sufficient asymmetry in the acceleration of the fluid on either side of the collapsing bubble, then the more rapidly moving fluid may deform the bubble into a toroidal shape, causing a high-velocity jet to be emitted on the opposite side. Microjetting has been reported to be capable of producing pitting even in highly resilient materials such as steel (Naudé and Ellis 1961; Benjamin and Ellis 1966). However, as both the direction and velocity of the jet are determined by the elastic properties of the nearby surface, its effects in biological tissue are more difficult to predict (Kudo and Kinoshita 2014). Nevertheless, as reported by Chen et al. (2011), in many cases a bubble will be sufficiently confined that microjetting will have an impact on surrounding structures regardless of jet direction.

-

5.

Shock waves: An inertially collapsing cavity that results in supersonic bubble wall velocities creates a significant discontinuity in the pressure in the surrounding liquid leading to the emission of a shock wave, which may impose significant stresses on nearby structures.

-

6.

Secondary radiation force: At smaller amplitudes of oscillation, a bubble will also generate a pressure wave in the surrounding fluid. If the bubble is adjacent to a surface, interaction between this wave and its reflection from the surface leads to a pressure gradient in the liquid and a secondary radiation force on the bubble. As with microjetting, the elastic properties of the boundary will determine the phase difference between the radiated and reflected waves and, hence, whether the bubbles move toward or away from the surface. Motion toward the surface may amplify the effects of phenomena 1, 3 and 6.

Thermal effects

As described above, an oscillating microbubble will re-radiate energy from the incident ultrasound field in the form of a spherical pressure wave. In addition, the non-linear character of the microbubble oscillations will lead to the re-radiation of energy over a range of frequencies. At moderate driving pressures, the bubble spectrum will contain integer multiples (harmonics) of the driving frequency; and at higher pressures, also fractional components (sub- and ultraharmonics). In biological tissue, absorption of ultrasound increases with frequency and this non-linear behavior thus also increases the rate of heating (Hilgenfeldt et al. 2000; Holt and Roy 2001). Bubbles will also dissipate energy as a result of viscous friction in the liquid and thermal conduction from the gas core, the temperature of which increases during compression. Which mechanism is dominant depends on the size of the bubble, the driving conditions and the viscosity of the medium. Thermal damping is, however, typically negligible in biomedical applications of ultrasound as the time constant associated with heat transfer is much longer than the period of the microbubble oscillations (Prosperetti 1977).

Chemical effects

The temperature rise produced in the surrounding tissue will be negligible compared with that occurring inside the bubble, especially during inertial collapse when it may reach several thousand Kelvin (Flint and Suslick 1991). The gas pressure similarly increases significantly. Although only sustained for a very brief period, these extreme conditions can produce highly reactive chemical species, in particular reactive oxygen species (ROS), as well as the emission of electromagnetic radiation (sonoluminescence). ROS have been reported to play a significant role in multiple biological processes (Winterbourn 2008), and both ROS and sonoluminescence may affect drug activity (Rosenthal et al. 2004; Trachootham et al. 2009; Beguin et al. 2019).

Physics of droplet–cell interaction

Droplets consist of an encapsulated quantity of a volatile liquid, such as perfluorobutane (boiling point: –1.7°C) or perfluoropentane (boiling point: 29°C), which is in a superheated state at body temperature. Superheated state means that although the volatile liquids have a boiling point below 37°C, these droplets remain in the liquid phase and do not exhibit spontaneous vaporization after injection. Vaporization can be achieved instead by exposure to ultrasound of significant amplitude via a process known as acoustic droplet vaporization (ADV) (Kripfgans et al. 2000). Before vaporization, the droplets are typically one order of magnitude smaller than the emerging bubbles, and the perfluorocarbon is inert and biocompatible (Biro and Blais 1987). These properties enable a range of therapeutic possibilities (Sheeran and Dayton 2012; Lea-Banks et al. 2019). For example, unlike microbubbles, small droplets may extravasate from the leaky vessels into tumor tissue because of the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect (Long et al. 1978; Lammers et al. 2012; Maeda 2012), and then be turned into bubbles by ADV (Rapoport et al. 2009; Kopechek et al. 2013). Loading the droplets with a drug enables local delivery (Rapoport et al. 2009) by way of ADV. The mechanism behind this is that the emerging bubbles give rise to similar radiation forces and microstreaming as described earlier in the Physics of the Microbubble–Cell Interaction. It should be noted that oxygen is taken up during bubble growth (Radhakrishnan et al. 2016), which could lead to hypoxia.

The physics of the droplet–cell interaction is largely governed by the ADV. In general, it has been observed that ADV is promoted by the following factors: large peak negative pressures (Kripfgans et al. 2000), usually obtained by strong focusing of the generated beam, high frequency of the emitted wave and a relatively long distance between the transducer and the droplet. Another observation that has been made with micrometer-sized droplets is that vaporization often starts at a well-defined nucleation spot near the side of the droplet where the acoustic wave impinges (Shpak et al. 2014). These facts can be explained by considering the two mechanisms that play a role in achieving a large peak negative pressure inside the droplet: acoustic focusing and non-linear ultrasound propagation (Shpak et al. 2016). In the following, lengths and sizes are related to the wavelength, that is, the distance traveled by a wave in one oscillation (e.g., a 1-MHz ultrasound wave that is traveling in water with a wave speed, c, of 1500 m/s has a wavelength, w (m), of c/f = 1500/106 = 0.0015, that is, 1.5 mm.

Acoustic focusing

Because the speed of sound in perfluorocarbon liquids is significantly lower than that in water or tissue, refraction of the incident wave will occur at the interface between these fluids, and the spherical shape of the droplet will give rise to focusing. The assessment of this focusing effect is not straightforward because the traditional way of describing these phenomena with rays that propagate along straight lines (the ray approach) holds only for objects that are much larger than the applied wavelength. In the current case, the frequency of a typical ultrasound wave used for insonification is in the order of 1–5 MHz, yielding wavelengths in the order of 1500–300 µm, while a droplet will be smaller by two to four orders of magnitude. In addition, using the ray approach, the lower speed of sound in perfluorocarbon would yield a focal spot near the backside of the droplet, which is in contradiction to observations. The correct way to treat the focusing effect is to solve the full diffraction problem by decomposing the incident wave, the wave reflected by the droplet and the wave transmitted into the droplet into a series of spherical waves. For each spherical wave, the spherical reflection and transmission coefficients can be derived. Superposition of all the spherical waves yields the pressure inside the droplet. Nevertheless, when this approach is only applied to an incident wave with the frequency that is emitted by the transducer, this will lead neither to the right nucleation spot nor to sufficient negative pressure for vaporization. Nanoscale droplets may be too small to make effective use of the focusing mechanism, and ADV is therefore less dependent on the frequency.

Non-linear ultrasound propagation

High pressure amplitudes, high frequencies and long propagation distances all promote non-linear propagation of an acoustic wave (Hamilton and Blackstock 2008). In the time domain, non-linear propagation manifests as an increasing deformation of the shape of the ultrasound wave with distance traveled. In the frequency domain, this translates to increasing harmonic content, that is, frequencies that are multiples of the driving frequency. The total incident acoustic pressure p(t) at the position of a nanodroplet can therefore be written as

| (2) |

where n is the number of a harmonic, an and ϕn are the amplitude and phase of this harmonic and ω is the angular frequency of the emitted wave. The wavelength of a harmonic wave is a fraction of the emitted wavelength.

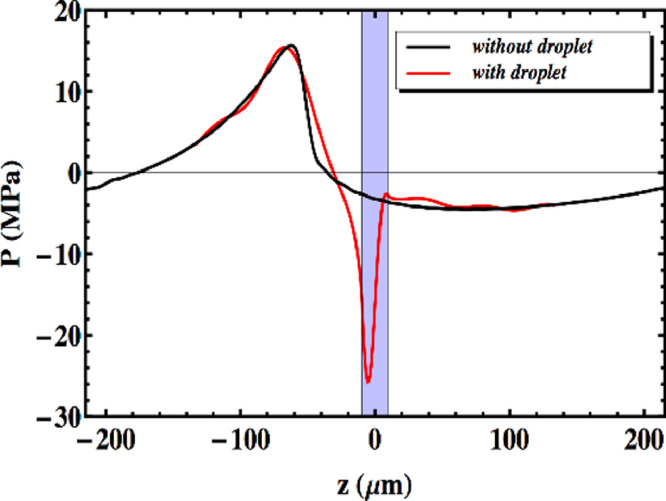

The aforementioned effects are both important in the case of ADV and should therefore be combined. This implies that first the amplitudes and phases of the incident non-linear ultrasound wave at the droplet location should be computed. Next, for each harmonic, the diffraction problem should be solved in terms of spherical harmonics. Adding the diffracted waves inside the droplet with the proper amplitude and phase will then yield the total pressure in the droplet. Figure 1 illustrates that the combined effects of non-linear propagation and diffraction can cause a dramatic amplification of the peak negative pressure in the micrometer-sized droplet, sufficient for triggering droplet vaporization (Shpak et al. 2014). Moreover, the location of the negative pressure peak also agrees with the observed nucleation spot.

Fig. 1.

Combined effect of non-linear propagation and focusing of the harmonics in a perfluoropentane micrometer-sized droplet. The emitted ultrasound wave has a frequency of 3.5 MHz and a focus at 3.81 cm, and the radius of the droplet is 10 µm for ease of observation. The pressures are given on the axis of the droplet along the propagating direction of the ultrasound wave, and the shaded area indicates the location of the droplet. Reprinted with permission from Sphak et al. (2014).

After vaporization has started, the growth of the emerging bubble is limited by inertia and heat transfer. In the absence of the heat transfer limitation, the inertia of the fluid that surrounds the bubble limits the rate of bubble growth, which is linearly proportional to time and inversely proportional to the square root of the density of the surrounding fluid. When inertia is neglected, thermal diffusion is the limiting factor in the transport of heat to drive the endothermic vaporization process of perfluorocarbon, causing the radius of the bubble to increase with the square root of time. In reality, both processes occur simultaneously, where the inertia effect is dominant at the early stage and the diffusion effect is dominant at the later stage of bubble growth. The final size that is reached by a bubble depends on the time that a bubble can expand, that is, on the duration of the negative cycle of the insonifying pressure wave. It is therefore expected that lower insonification frequencies give rise to larger maximum bubble size. Thus, irrespective of their influence on triggering ADV, lower frequencies would lead to more violent inertial cavitation effects and cause more biological damage, as experimentally observed for droplets with a radius in the order of 100 nm (Burgess and Porter 2019).

Biological mechanisms and bio-effects of ultrasound-activated cavitation nuclei

The biological phenomena of sonoporation (i.e., membrane pore formation), stimulated endocytosis and opening of cell–cell contacts and the bio-effects of intracellular calcium transients, ROS generation, cell membrane potential change and cytoskeleton changes have been observed for several years (Sutton et al. 2013; Kooiman et al. 2014; Lentacker et al. 2014; Qin et al. 2018b). However, other bio-effects induced by ultrasound-activated cavitation nuclei have recently been discovered. These include membrane blebbing as a recovery mechanism for reversible sonoporation (both for ultrasound-activated microbubbles [Leow et al. 2015] and upon ADV [Qin et al. 2018a]), extracellular vesicle formation (Yuana et al. 2017), suppression of efflux transporter P-glycoprotein (Cho et al. 2016; Aryal et al. 2017) and BBB (blood–brain barrier) transporter genes (McMahon et al. 2018). At the same time, more insight has been gained into the origin of the bio-effects, largely through the use of live cell microscopy. For sonoporation, real-time membrane pore opening and closure dynamics were revealed with pores <30 µm2 closing within 1 min, while pores >100 µm2 did not reseal (Hu et al. 2013) as well as immediate rupture of filamentary actin at the pore location (Chen et al. 2014) and correlation of intracellular ROS levels with the degree of sonoporation (Jia et al. 2018). Real-time sonoporation and opening of cell–cell contacts in the same endothelial cells have been reported as well for a single example (Helfield et al. 2016). The applied acoustic pressure was found to determine uptake of model drugs via sonoporation or endocytosis in another study (De Cock et al. 2015). Electron microscopy revealed formation of transient membrane disruptions and permanent membrane structures, that is, caveolar endocytic vesicles, upon ultrasound and microbubble treatment (Zeghimi et al. 2015). A study by Fekri et al. (2016) revealed that enhanced clathrin-mediated endocytosis and fluid-phase endocytosis occur through distinct signaling mechanisms upon ultrasound and microbubble treatment. The majority of these bio-effects have been observed in in vitro models using largely non-endothelial cells and may therefore not be directly relevant to in vivo tissue, where intravascular micron-sized cavitation nuclei will only have contact with endothelial cells and circulating blood cells. On the other hand, the mechanistic studies by Belcik et al. (2015, 2017) and Yu et al. (2017) do reveal translation from in vitro to in vivo. In these studies, ultrasound-activated microbubbles were found to induce a shear-dependent increase in intravascular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) from both endothelial cells and erythrocytes, an increase in intramuscular nitric oxide and downstream signaling through both nitric oxide and prostaglandins, which resulted in augmentation of muscle blood flow. Ultrasound settings were similar, namely, 1.3 MHz, mechanical index (MI) 1.3 for Belcik et al. (2015, 2017) and 1 MHz, MI 1.5 for Yu et al. (2017), with MI defined as MI = P–/ , where P_ is the derated peak negative pressure of the ultrasound wave (in MPa) and f the center frequency of the ultrasound wave (in MHz).

Whether or not there is a direct relationship between the type of microbubble oscillation and specific bio-effects remains to be elucidated, although more insight has been gained through ultrahigh-speed imaging of the microbubble behavior in conjunction with live cell microscopy. For example, there seems to be a microbubble excursion threshold above which sonoporation occurs (Helfield et al. 2016). Van Rooij et al. (2016) further found that displacement of targeted microbubbles enhanced reversible sonoporation and preserved cell viability, whilst microbubbles that did not displace were identified as the main contributors to cell death.

All of the aforementioned biological observations, mechanisms and effects relate to eukaryotic cells. Study of the biological effects of cavitation on, for example, bacteria is in its infancy, but studies suggest that sonoporation can be achieved in Gram-negative bacteria, with dextran uptake and gene transfection being reported in Fusobacterium nucleatum (Han et al. 2007). More recent studies have investigated the effect of microbubbles and ultrasound on gene expression (Li et al. 2015; Dong et al. 2017; Zhou et al. 2018). The findings are conflicting because although they all reveal a reduction in expression of genes involved in biofilm formation and resistance to antibiotics, an increase in expression of genes involved with dispersion and detachment of biofilms was also found (Dong et al. 2017). This cavitation-mediated bio-effect needs further investigation.

Modelling microbubble–cell–drug interaction

Whilst there have been significant efforts to model the dynamics of ultrasound-driven microbubbles (Faez et al. 2013; Dollet et al. 2019), less attention has been paid to the interactions between microbubbles and cells or their impact upon drug transport. Currently there are no models that describe the interactions between microbubbles, cells and drug molecules. Several models have been proposed for the microbubble–cell interaction in sonoporation focusing on different aspects: cell expansion and microbubble jet velocity (Guo et al. 2017b), the shear stress exerted on the cell membrane (Wu 2002; Doinikov and Bouakaz 2010; Forbes and O'Brien 2012; Yu and Chen 2014; Cowley and McGinty 2019), microstreaming (Yu and Chen 2014), the shear stress exerted on the cell membrane in combination with microstreaming (Li et al. 2014) or other flow phenomena (Yu et al. 2015; Rowlatt and Lind 2017) generated by an oscillating microbubble. In contrast to the other models, Man et al. (2019) propose that the microbubble-generated shear stress does not induce pore formation, but is instead due to microbubble fusion with the membrane and subsequent “pull out” of cell membrane lipid molecules by the oscillating microbubble. Models for pore formation (e.g., Koshiyama and Wada 2011) and resealing (Zhang et al. 2019) in cell membranes have also been developed, but these models neglect the mechanism by which the pore is created. There is just one sonoporation dynamics model, developed by Fan et al. (2012), that relates the uptake of the model drug propidium iodide (PI) to the size of the created membrane pore and the pore resealing time for a single cell in an in vitro setting. The model describes the intracellular fluorescence intensity of PI as a function of time, F(t), by

| (3) |

where α is the coefficient that relates the amount of PI molecules to the fluorescence intensity of PI-DNA and PI-RNA, D is the diffusion coefficient of PI, C0 is the extracellular PI concentration, r0 is the initial radius of the pore, β is the pore re-sealing coefficient and t is time. The coefficient α is determined by the sensitivity of the fluorescence imaging system, and if unknown, the equation can still be used because it is the pore size coefficient, α·πDC0·r0, that determines the initial slope of the PI uptake pattern and is the scaling factor for the exponential increase. A cell with a large pore will have a steep initial slope of PI uptake, and the maximum PI intensity quickly reaches the plateau value. A limitation of this model is that eqn (3) is based on 2-D free diffusion models, which holds for PI-RNA but not for PI-DNA because the latter is confined to the nucleus. The model is independent of cell type, as Fan et al. have reported agreement with experimental results in both kidney (Fan et al. 2012) and endothelial cells (Fan et al. 2013). Other researchers have also used this model for endothelial cell studies and also classified the distribution of both the pore size and pore resealing coefficients using principal component analysis (PCA) to determine whether cells were reversibly or irreversibly sonoporated. In the context of BBB opening, Hosseinkhah et al. (2015) have modeled the microbubble-generated shear and circumferential wall stress for 5-µm microvessels upon microbubble oscillation at a fixed MI of 0.134 for a range of frequencies (0.5, 1 and 1.5 MHz). The wall stresses were dependent upon microbubble size (range investigated: 2–18 µm in diameter) and ultrasound frequency. Wiedemair et al. (2017) have also modelled the wall shear stress generated by microbubble (2 µm in diameter) destruction at 3 MHz for larger microvessels (200 µm in diameter). The presence of red blood cells was included in the model and was found to cause confinement of pressure and shear gradients to the vicinity of the microbubble. Advances in methods for imaging microbubble–cell interactions will facilitate the development of more sophisticated mechanistic models.

Treatment of tumors (non-brain)

The structure of tumor tissue varies significantly from that of healthy tissue which has important implications for its treatment. To support the continuous expansion of neoplastic cells, the formation of new vessels (i.e., angiogenesis) is needed (Junttila and de Sauvage 2013). As such, a rapidly developed, poorly organized vasculature with enlarged vascular openings arises. Between these vessels, large avascular regions exist, which are characterized by a dense extracellular matrix, high interstitial pressure, low pH and hypoxia. Moreover, a local immunosuppressive environment is formed, preventing possible anti-tumor activity by the immune system.

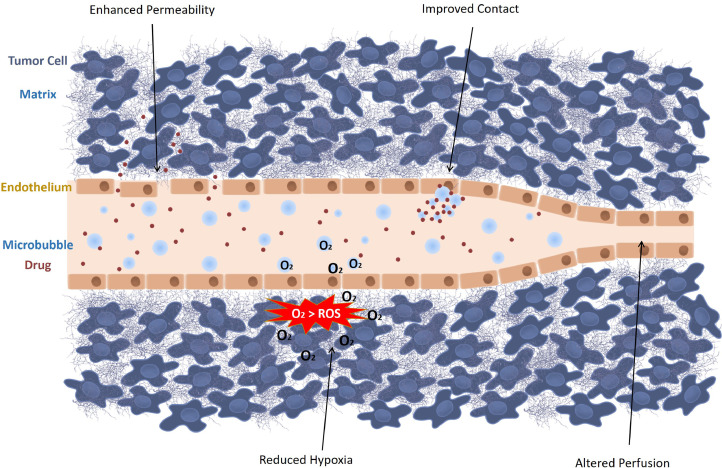

Notwithstanding the growing knowledge of the pathophysiology of tumors, treatment remains challenging. Chemotherapeutic drugs are typically administered to abolish the rapidly dividing cancer cells. Yet, their cytotoxic effects are not limited to cancer cells, causing dose-limiting off-target effects. To overcome this hurdle, chemotherapeutics are often encapsulated in nano-sized carriers, that is, nanoparticles, that are designed to specifically diffuse through the large openings of tumor vasculature, while being excluded from healthy tissue by normal blood vessels (Lammers et al. 2012; Maeda 2012). Despite being highly promising in pre-clinical studies, drug-containing nanoparticles have exhibited limited clinical success because of the vast heterogeneity in tumor vasculature (Barenholz 2012; Lammers et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2015d). In addition, drug penetration into the deeper layers of the tumor can be constrained by high interstitial pressure and a dense extracellular matrix in the tumor. Furthermore, acidic and hypoxic regions limit the efficacy of radiation- and chemotherapy-based treatments because of biochemical effects (Mehta et al. 2012; McEwan et al. 2015; Fix et al. 2018). Ultrasound-triggered microbubbles are able to alter the tumor environment locally, thereby improving drug delivery to tumors. These alterations are schematically represented in Figure 2 and include improving vascular permeability, modifying the tumor perfusion, reducing local hypoxia and overcoming the high interstitial pressure.

Fig. 2.

Ultrasound-activated microbubbles can locally alter the tumor microenvironment through four mechanisms: enhanced permeability, improved contact, reduced hypoxia and altered perfusion. ROS = reactive oxygen species.

Several studies have found that ultrasound-driven microbubbles improved delivery of chemotherapeutic agents in tumors, which resulted in increased anti-tumor effects (Wang et al. 2015d; Snipstad et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2018). Moreover, several gene products could be effectively delivered to tumor cells via ultrasound-driven microbubbles, resulting in a downregulation of tumor-specific pathways and an inhibition in tumor growth (Kopechek et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2015). Theek et al. (2016) furthermore confirmed that nanoparticle accumulation can be achieved in tumors with low EPR effect. Drug transport and distribution through the dense tumor matrix and into regions with elevated interstitial pressure are often the limiting factors in peripheral tumors. As a result, several reports have indicated that drug penetration into the tumor remained limited after sonoporation, which may impede the eradication of the entire tumor tissue (Eggen et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2015d; Wei et al. 2019). Alternatively, microbubble cavitation can affect tumor perfusion, as vasoconstriction and even temporary vascular shutdown have been reported ex vivo (Keravnou et al. 2016) and in vivo (Hu et al. 2012; Goertz 2015; Yemane et al. 2018). These effects were seen at higher ultrasound intensities (>1.5 MPa) and are believed to result from inertial cavitation leading to violent microbubble collapses. As blood supply is needed to maintain tumor growth, vascular disruption might form a different approach to cease tumor development. Microbubble-induced microvascular damage was able to complement the direct effects of chemotherapeutics and antivascular drugs by secondary ischemia-mediated cytotoxicity, which led to tumor growth inhibition (Wang et al. 2015a; Ho et al. 2018; Yang et al. 2019b). In addition, a synergistic effect between radiation therapy and ultrasound-stimulated microbubble treatment was observed, as radiation therapy also induces secondary cell death by endothelial apoptosis and vascular damage (Lai et al. 2016; Daecher et al. 2017). Nevertheless, several adverse effects have been reported because of excessive vascular disruption, including hemorrhage, tissue necrosis and the formation of thrombi (Goertz 2015; Wang et al. 2015d; Snipstad et al. 2017).

Furthermore, oxygen-containing microbubbles can provide a local oxygen supply to hypoxic areas, rendering oxygen-dependent treatments more effective. This is of interest for sonodynamic therapy, which is based on the production of cytotoxic ROS by a sonosensitizing agent upon activation by ultrasound in the presence of oxygen (McEwan et al. 2015, 2016; Nesbitt et al. 2018). As ultrasound can be used to stimulate the release of oxygen from oxygen-carrying microbubbles while simultaneously activating a sonosensitizer, this approach has been reported to be particularly useful for the treatment of hypoxic tumor types (McEwan et al. 2015; Nesbitt et al. 2018). Additionally, low oxygenation promotes resistance to radiotherapy, which can be circumvented by a momentary supply of oxygen. Based on this notion, oxygen-carrying microbubbles were used to improve the outcome of radiotherapy in a rat fibrosarcoma model (Fix et al. 2018).

Finally, ultrasound-activated microbubbles promote convection and induce acoustic radiation forces. As such, closer contact with the tumor endothelium and an extended contact time can be obtained (Kilroy et al. 2014). Furthermore, these forces may counteract the elevated interstitial pressure present in tumors (Eggen et al. 2014; Lea-Banks et al. 2016; Xiao et al. 2019).

Apart from their ability to improve tumor uptake, microbubbles can be used as ultrasound-responsive drug carriers to reduce the off-target effects of chemotherapeutics. By loading the drugs or drug-containing nanoparticles directly into or onto the microbubbles, a spatial and temporal control of drug release can be obtained, thereby reducing exposure to other parts of the body (Yan et al. 2013; Snipstad et al. 2017). Moreover, several studies have reported improved anti-cancer effects from treatment with drug-coupled microbubbles, compared with a co-administration approach (Burke et al. 2014; Snipstad et al. 2017). Additionally, tumor neovasculature expresses specific surface receptors that can be targeted by specific ligands. Adding such targeting moieties to the surface of (drug-loaded) microbubbles improves site-targeted delivery and has been found to potentiate this effect further (Bae et al. 2016; Xing et al. 2016; Luo et al. 2017).

Phase-shifting droplets and gas-stabilizing solid agents (e.g., nanocups) have the unique ability to benefit from both EPR-mediated accumulation in the “leaky” parts of the tumor vasculature because of their small sizes, as well as from ultrasound-induced permeabilization of the tissue structure (Zhou 2015; Myers et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2018b; Zhang et al. 2018). Several research groups have reported tumor regression after treatment with acoustically active droplets (Gupta et al. 2015; van Wamel et al. 2016; Cao et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2018b) or gas-stabilizing solid particles (Min et al. 2016; Myers et al. 2016). A different approach to the use of droplets for tumor treatment is ACT, which is based on microbubble-droplet clusters that upon ultrasound exposure, undergo a phase shift to create large bubbles that can transiently block capillaries (Sontum et al. 2015). Although the mechanism behind the technique is not yet fully understood, studies have reported improved delivery and efficacy of paclitaxel and Abraxane in xenograft prostate tumor models (van Wamel et al. 2016; Kotopoulis et al. 2017). Another use of droplets for tumor treatment is enhanced high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU)-mediated heating of tumors (Kopechek et al. 2014).

Although microbubble-based drug delivery to solid tumors shows great promise, it also faces important challenges. The ultrasound parameters used in in vivo studies highly vary between research groups, and no consensus was found on the oscillation regime that is believed to be responsible for the observed effects (Wang et al. 2015d; Snipstad et al. 2017). Moreover, longer ultrasound pulses and increased exposure times are usually applied in comparison to in vitro reports (Roovers et al. 2019c). This could promote additional effects such as microbubble clustering and microbubble translation, which could cause local damage to the surrounding tissue as well (Roovers et al. 2019a). To elucidate these effects further, fundamental in vitro research remains important. Therefore, novel in vitro models that more accurately mimic the complexity of the in vivo tumor environment are currently being explored. Park et al. (2016) engineered a perfusable vessel-on-a-chip system and reported successful doxorubicin delivery to the endothelial cells lining this microvascular network. While such microfluidic chips could be extremely useful to study the interactions of microbubbles with the endothelial cell barrier, special care of the material of the chambers should be taken to avoid ultrasound reflections and standing waves (Beekers et al. 2018). Alternatively, 3-D tumor spheroids have been used to study the effects of ultrasound and microbubble-assisted drug delivery on penetration and therapeutic effect in a multicellular tumor model (Roovers et al. 2019b). Apart from expanding the knowledge on microbubble–tissue interactions in detailed parametric studies in vitro, it will be crucial to obtain improved control over the microbubble behavior in vivo, and link this to the therapeutic effects. To this end, passive cavitation detection to monitor microbubble cavitation behavior in real time is currently under development, and could provide better insights in the future (Choi et al. 2014; Graham et al. 2014; Haworth et al. 2017). Efforts are being committed to construction of custom-built delivery systems, which can be equipped with multiple transducers allowing drug delivery guided by ultrasound imaging and/or passive cavitation detection (Escoffre et al. 2013; Choi et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2015c; Paris et al. 2018).

Clinical studies

Pancreatic cancer

The tolerability and therapeutic potential of improved chemotherapeutic drug delivery using microbubbles and ultrasound were first investigated for the treatment of inoperable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma at Haukeland University Hospital, Norway (Kotopoulis et al. 2013; Dimcevski et al. 2016). In this clinical trial, gemcitabine was administered by intravenous injection over 30 min. During the last 10 min of chemotherapy, an abdominal echography was performed to locate the position of pancreatic tumor. At the end of chemotherapy, 0.5 mL of SonoVue microbubbles followed by 5 mL saline was intravenously injected every 3.5 min to ensure their presence throughout the whole sonoporation treatment. Pancreatic tumors were exposed to ultrasound (1.9 MHz, MI 0.2, 1% DC) using a 4C curvilinear probe (GE Healthcare) connected to an LOGIQ 9 clinical ultrasound scanner. The cumulative ultrasound exposure was only 18.9 s. All clinical data indicated that microbubble-mediated gemcitabine delivery did not induce any serious adverse events in comparison to chemotherapy alone. At the same time, tumor size and development were characterized according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria. In addition, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status was used to monitor the therapeutic efficacy of microbubble-mediated gemcitabine delivery. All 10 patients tolerated an increased number of gemcitabine cycles compared with treatment with chemotherapy alone from historical controls (8.3 ± 6 vs. 13.8 ± 5.6 cycles, p < 0.008), thus reflecting an improved physical state. After 12 treatment cycles, one patient's tumor exhibited a twofold decrease in tumor size. This patient was excluded from this clinical trial to be treated with radiotherapy and then with pancreatectomy. In 5 of the 10 patients, the maximum tumor diameter was partially decreased from the first to last therapeutic treatment. Subsequently, a consolidative radiotherapy or a FOLFIRINOX treatment, a bolus and infusion of 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan and oxaliplatin, was offered to them. The median survival was significantly increased from 8.9 to 17.6 mo (p = 0.0001). Together, these results indicate that drug delivery using clinically approved microbubbles, chemotherapeutics and ultrasound is feasible and compatible with respect to clinical procedures. Nevertheless, the authors did not provide any evidence that the improved therapeutic efficacy of gemcitabine was related to an increase in intra-tumoral bioavailability of the drug. In addition, the effects of microbubble-assisted ultrasound treatment alone on tumor growth were not investigated, while recent publications describe that according to the ultrasound parameters, such treatment could induce a significant decrease in tumor volume through a reduction in tumor perfusion as described above.

Hepatic metastases from the digestive system

A tolerability study of chemotherapeutic delivery using microbubble-assisted ultrasound for the treatment of liver metastases from gastrointestinal tumors and pancreatic carcinoma was conducted at Beijing Cancer Hospital, China (Wang et al. 2018). Thirty minutes after intravenous infusion of chemotherapy (for both monotherapy and combination therapy), 1 mL of SonoVue microbubbles was intravenously administered and was repeated another five times in 20 min. An ultrasound probe (C1-5 abdominal convex probe; GE Healthcare, USA) was positioned on the tumor lesion, which was exposed to ultrasound at different MIs (0.4–1) in contrast mode using a LogiQ E9 scanner (GE Healthcare, USA). The primary aims of this clinical trial were to evaluate the tolerability of this therapeutic procedure and to explore the largest MI and ultrasound treatment time that cancer patients can tolerate. According to the clinical tolerability evaluation, all 12 patients exhibited no serious adverse events. The authors reported that the microbubble-mediated chemotherapy led to fever in 2 patients. However, there is no clear evidence this is related to the microbubble and ultrasound treatment. Indeed, in the absence of direct comparison of these results with a historical group of patients receiving the chemotherapy on its own, one cannot rule out a direct link between the fever and the chemotherapy alone. All adverse side effects were resolved with symptomatic medication. In addition, the severity of side effects did not worsen with increases in MI, suggesting that microbubble-mediated chemotherapy is a tolerable procedure. The secondary aims were to assess the efficacy of this therapeutic protocol using contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Thus, tumor size and development were characterized according to the RECIST criteria. Half of the patients had stable disease, and one patient obtained a partial response after the first treatment cycle. The median progression-free survival was 91 d. However, comparison and interpretation of results are very difficult because none of the patients were treated with the same chemotherapeutics, MI and/or number of treatment cycles. The results of tolerability and efficacy evaluations should be compared with those for patients receiving the chemotherapy on its own to clearly identify the therapeutic benefit of combining therapy with ultrasound-driven microbubbles. Similar to the pancreatic clinical study, no direct evidence of enhanced therapeutic bioavailability of the chemotherapeutic drug after the treatment was provided. This investigation is all the more important as the ultrasound and microbubble treatment was applied 30 min after intravenous chemotherapy (for both monotherapy and combination therapy) independently of drug pharmacokinetics and metabolism.

Ongoing and upcoming clinical trials

Currently, two clinical trials are ongoing: (i) Professor F. Kiessling (RWTH Aachen University, Germany) proposes examining whether the exposure of early primary breast cancer to microbubble-assisted ultrasound during neoadjuvant chemotherapy results in increased tumor regression in comparison to that after ultrasound treatment alone (NCT03385200). (ii) Dr. J. Eisenbrey (Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center, Thomas Jefferson University, USA) is investigating the therapeutic potential of perflutren protein type A microspheres in combination with microbubble-assisted ultrasound in radioembolization therapy of liver cancer (NCT03199274).

A proof of concept study (NCT03458975) has been set in Tours Hospital, France, for treating non-resectable liver metastases. The aim of this trial is to perform a feasibility study with the development of a dedicated ultrasound imaging and delivery probe with a therapy protocol optimized for patients with hepatic metastases of colorectal cancer and who are eligible for monoclonal antibodies in combination with chemotherapy. A dedicated 1.5-D ultrasound probe has been developed and interconnected to a modified Aixplorer imaging platform (Supersonic Imagine, Aix-en-Provence, France). The primary objective of the study is to determine the rate of objective response at 2 mo for lesions receiving optimized and targeted delivery of systemic chemotherapy combining bevacizumab and FOLFIRI compared with those treated with only the systemic chemotherapy regimen. The secondary objective is to determine the tolerability of this local approach of optimized intra-tumoral drug delivery during the 3 mo of follow-up, by assessing tumor necrosis, tumor vascularity and pharmacokinetics of bevacizumab and by profiling cytokine expression spatially.

Immunotherapy

Cancer immunotherapy is considered to be one of the most promising strategies to eradicate cancer as it makes use of the patient's own immune system to selectively attack and destroy tumor cells. It is a common name that refers to a variety of strategies that aim to unleash the power of the immune system by either boosting antitumoral immune responses or flagging tumor cells to make them more visible to the immune system. The principle is that tumors express specific tumor antigens which are not expressed or expressed to a much lesser extent by normal somatic cells and hence can be used to initiate a cancer-specific immune response. In this section we aim to give insight into how microbubbles and ultrasound have been applied as useful tools to initiate or sustain different types of cancer immunotherapy, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Fig. 3.

Schematic overview of how microbubbles (MB) and ultrasound (US) have been found to contribute to cancer immunotherapy. From left to right: Microbubbles can be used as antigen carriers to stimulate antigen uptake by dendritic cells. Microbubbles and ultrasound can alter the permeability of tumors, thereby increasing the intra-tumoral penetration of adoptively transferred immune cells or checkpoint inhibitors. Finally, exposing tissues to cavitating microbubbles can induce sterile inflammation by the local release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPS).

When Ralph Steinman (Steinman et al. 1979) discovered the dendritic cell (DC) in 1973, its central role in the initiation of immunity made it an attractive target to evoke specific antitumoral immune responses. Indeed, these cells very efficiently capture antigens and present them to T lymphocytes in major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs), thereby bridging the innate and adaptive immune systems. More specifically, exogenous antigens engulfed via the endolysosomal pathway are largely presented to CD4+ T cells via MHC-II, whereas endogenous, cytoplasmic proteins are shuttled to MHC-I molecules for presentation to CD8+ cells. As such, either CD4+ helper T cells or CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell responses are induced. The understanding of this pivotal role played by DCs formed the basis for DC-based vaccination, where a patient's DCs are isolated, modified ex vivo to present tumor antigens and re-administered as a cellular vaccine. DC-based therapeutics, however, suffer from a number of challenges, of which the expensive and lengthy ex vivo procedure for antigen loading and activation of DCs is the most prominent (Santos and Butterfield 2018). In this regard, microbubbles have been investigated for direct delivery of tumor antigens to immune cells in vivo. Bioley et al. (2015) reported that intact microbubbles are rapidly phagocytosed by both murine and human DCs, resulting in rapid and efficient uptake of surface-coupled antigens without the use of ultrasound. Subcutaneous injection of microbubbles loaded with the model antigen ovalbumin (OVA) resulted in the activation of both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. Effectively, these T-cell responses could partially protect vaccinated mice against an OVA-expressing Listeria infection. Dewitte et al. (2014) investigated a different approach, making use of messenger RNA (mRNA)-loaded microbubbles combined with ultrasound to transfect DCs. As such, they were able to deliver mRNA encoding both tumor antigens and immunomodulating molecules directly to the cytoplasm of the DCs. As a result, preferential presentation of antigen fragments in MHC-I complexes was ensured, favoring the induction of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. In a therapeutic vaccination study in mice bearing OVA-expressing tumors, injection of mRNA-sonoporated DCs caused a pronounced slowdown of tumor growth and induced complete tumor regression in 30% of the vaccinated animals. Interestingly, in humans, intradermally injected microbubbles have been used as sentinel lymph node detectors as they can easily drain from peripheral sites to the afferent lymph nodes (Sever et al. 2012a, 2012b). As lymph nodes are the primary sites of immune induction, the interaction of microbubbles with intranodal DCs, could be of high value. To this end, Dewitte et al. (2015) found that mRNA-loaded microbubbles were able to rapidly and efficiently migrate to the afferent lymph nodes after intradermal injection in healthy dogs. Unfortunately, further translation of this concept to an in vivo setting is not straightforward, as it prompts the use of less accessible large animal models (e.g., pigs, dogs). Indeed, conversely to what has been reported in humans, lymphatic drainage of subcutaneously injected microbubbles is very limited in the small animal models typically used in pre-clinical research (mice and rats), which is the result of substantial differences in lymphatic physiology.

Another strategy in cancer immunotherapy is adoptive cell therapy, in which ex vivo manipulated immune effector cells, mainly T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, are employed to generate a robust and selective anticancer immune response (Yee 2018; Hu et al. 2019). These strategies have mainly led to successes in hematological malignancies, not only because of the availability of selective target antigens, but also because of the accessibility of the malignant cells (Khalil et al. 2016; Yee 2018). By contrast, in solid tumors, and especially in brain cancers, inadequate homing of cytotoxic T cells or NK cells to the tumor proved to be one of the main reasons for the low success rates, making the degree of tumor infiltration an important factor in disease prognosis (Childs and Carlsten 2015; Gras Navarro et al. 2015; Yee 2018). To address this, focused ultrasound and microbubbles have been used to make tumors more accessible to cellular therapies. The first demonstration of this concept was provided by Alkins et al. (2013), who used a xenograft HER-2-expressing breast cancer brain metastasis model to determine whether ultrasound and microbubbles could allow intravenously infused NK cells to cross the BBB. By loading the NK cells with superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles, the accumulation of NK cells in the brain could be tracked and quantified via MRI. An enhanced accumulation of NK cells was found when the cells were injected immediately before BBB disruption. Importantly NK cells retained their activity and ultrasound treatment resulted in a sufficient NK-to-tumor cell ratio to allow effective tumor cell killing (Alkins et al. 2016). In contrast, very few NK cells reached the tumor site when BBB disruption was absent or performed before NK cell infusion. Although it is not known for certain why timing had such a significant impact on NK extravasation, it is likely that the most effective transfer to the tissue occurs at the time of insonification, and that the barrier is most open during this time (Marty et al. 2012). Possible other explanations include the difference in size of the temporal BBB openings or a possible alternation in the expression of specific leukocyte adhesion molecules by the BBB disruption, thus facilitating the translocation of NK cells. Also, for tumors where BBB crossing is not an issue, ultrasound has been used to improve delivery of cellular therapeutics. Sta Maria et al. (2015) reported enhanced tumor infiltration of adoptively transferred NK cells after treatment with microbubbles and low-dose focused ultrasound. This result was confirmed by Yang et al. (2019a) in a more recent publication where the homing of NK cells more than doubled after microbubble injection and ultrasound treatment of an ovarian tumor. Despite the enhanced accumulation, however, the authors did not observe an improved therapeutic effect, which might be owing to the limited number of treatments that were applied or the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment that counteracts the cytotoxic action of the NK cells.

There is growing interest in exploring the effect of microbubbles and ultrasound on the tumor microenvironment, as recent work has indicated that BBB disruption with microbubbles and ultrasound may induce sterile inflammation. Although a strong inflammatory response may be detrimental in the case of drug delivery across the BBB, it might be interesting to further study this inflammatory response in solid tumors as it might induce the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPS) such as heat-shock proteins and inflammatory cytokines. This could shift the balance toward a more inflammatory microenvironment that could promote immunotherapeutic approaches. As reported by Liu et al. (2012) exposure of a CT26 colon carcinoma xenograft to microbubbles and low-pressure pulsed ultrasound increased cytokine release and triggered lymphocyte infiltration. Similar data have been reported by Hunt et al. (2015). In their study, ultrasound treatment caused a complete shutdown of tumor vasculature followed by the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α), a marker of tumor ischemia and tumor necrosis, as well as increased infiltration of T cells. Similar responses have been reported after thermal and mechanical HIFU treatments of solid tumors (Unga and Hashida 2014; Silvestrini et al. 2017). A detailed review of ablative ultrasound therapies is, however, out of the scope of this review.

At present, the most successful form of immunotherapy is the administration of monoclonal antibodies to inhibit regulatory immune checkpoints that block T-cell action. Examples are cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death 1 (PD-1), which act as brakes on the immune system. Blocking the effect of these brakes can revive and support the function of immune effector cells. Despite the numerous successes achieved with checkpoint inhibitors, responses have been quite heterogeneous as the success of checkpoint inhibition therapy depends largely on the presence of intra-tumoral effector T cells (Weber 2017). This motivated Bulner et al. (2019) to explore the synergy of microbubble and ultrasound treatment with PD-L1 checkpoint inhibition therapy in mice. Tumors in the treatment group that received the combination of microbubble and ultrasound treatment with checkpoint inhibition were significantly smaller than tumors in the monotherapy groups. One mouse exhibited complete tumor regression and remained tumor free upon rechallenge, indicative of an adaptive immune response.

Overall, the number of studies that have investigated the impact of microbubble and ultrasound treatment on immunotherapy is limited, making this a rather unexplored research area. It is obvious that more in-depth research is warranted to improve our understanding on how (various types of) immunotherapy might benefit from (various types of) ultrasound treatment.

BBB and blood–spinal cord barrier opening

The barriers of the central nervous system (CNS), the BBB and blood–spinal cord barrier (BSCB), greatly limit drug-based treatment of CNS disorders. These barriers help to regulate the specialized CNS environment by limiting the passage of most therapeutically relevant molecules (Pardridge 2005). Although several methods have been proposed to circumvent the BBB and BSCB, including chemical disruption and the development of molecules engineered to capitalize on receptor-mediated transport (so-called Trojan horse molecules), the use of ultrasound in combination with microbubbles (Hynynen et al. 2001) or droplets (Wu et al. 2018) to transiently modulate these barriers has come to the forefront in recent years because of the targeted nature of this approach and its ability to facilitate delivery of a wide range of currently available therapeutics. First demonstrated in 2001 (Hynynen et al. 2001), ultrasound-mediated BBB opening has been the topic of several hundred original research articles in the last two decades and, in recent years, has made headlines for groundbreaking clinical trials targeting brain tumors and Alzheimer's disease as described later under Clinical Studies.

Mechanisms, bio-effects and tolerability

Ultrasound in combination with microbubbles can produce permeability changes in the BBB via both enhanced paracellular and transcellular transport (Sheikov et al. 2004, 2006). Reduction and reorganization of tight junction proteins (Sheikov et al. 2008) and upregulation of active transport protein caveolin-1 (Deng et al. 2012) have been reported. Although the exact physical mechanisms driving these changes are not known, there are several factors that are hypothesized to contribute to these effects, including direct tensile stresses caused by the expansion and contraction of the bubbles in the lumen, as well as shear stresses at the vessel wall arising from acoustic microstreaming. Recent studies have also investigated the suppression of efflux transporters after ultrasound exposure with microbubbles. A reduction in P-glycoprotein expression (Cho et al. 2016; Aryal et al. 2017) and BBB transporter gene expression (McMahon et al. 2018) has been observed by multiple groups. One study found that P-glycoprotein expression was suppressed for more than 48 h after treatment with ultrasound and microbubbles (Aryal et al. 2017). However, the degree of inhibition of efflux transporters as a result of ultrasound with microbubbles may be insufficient to prevent efflux of some therapeutics (Goutal et al. 2018), and thus this mechanism requires further study.

Many studies have documented enhanced CNS tumor response after ultrasound and microbubble-mediated delivery of drugs across the blood–tumor barrier in rodent models. Improved survival has been observed in both primary (Chen et al. 2010; Aryal et al. 2013) and metastatic (Park et al. 2012; Alkins et al. 2016) tumor models.

Beyond simply enhancing drug accumulation in the CNS, several positive bio-effects of ultrasound and microbubble-induced BBB opening have been reported. In rodent models of Alzheimer's disease, numerous positive effects have been discovered in the absence of exogenous therapeutics. These effects include a reduction in amyloid-β plaque load (Jordão et al. 2013; Burgess et al. 2014; Leinenga and Götz 2015; Poon et al. 2018), reduction in tau pathology (Pandit et al. 2019) and improvements in spatial memory (Burgess et al. 2014; Leinenga and Götz 2015). Two-photon microscopy has revealed that amyloid-β plaque size is reduced in transgenic mice for up to 2 wk after ultrasound and microbubble treatment (Poon et al. 2018). Opening of the BBB in both transgenic and wild-type mice has also revealed enhanced neurogenesis (Burgess et al. 2014; Scarcelli et al. 2014; Mooney et al. 2016) in the treated tissue.

Gene delivery to the CNS using ultrasound and microbubbles is another area that is increasingly being investigated. Viral (Alonso et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2015b) and non-viral (Mead et al. 2016) delivery methods have been investigated. While early studies reported the feasibility of gene delivery using reporter genes (e.g., Thevenot et al. 2012; Alonso et al. 2013), there have been promising results delivering therapeutic genes. In particular, advances have been made in Parkinson's disease models, where therapeutic genes have been tested (Mead et al. 2017; Xhima et al. 2018) and where long-lasting functional improvements have been reported in response to therapy (Mead et al. 2017). It is expected that research into this highly promising technique will expand to a range of therapeutic applications.

Despite excellent tolerability profiles in non-human primate studies investigating repeat opening of the BBB (McDannold et al. 2012; Downs et al. 2015), there has been recent controversy because of reports of a sterile inflammatory response observed in rats (Kovacs et al. 2017a, 2017b; Silburt et al. 2017). The inflammatory response is proportional to the magnitude of BBB opening and is therefore strongly influenced by experimental conditions such as microbubble dose and acoustic settings. However, McMahon and Hynynen (2017) reported that when clinical microbubble doses are used, and treatment exposures are actively controlled to avoid overtreating, the inflammatory response is acute and mild. They note that while chronic inflammation is undesirable, acute inflammation may actually contribute to some of the positive bio-effects that have been observed. For example, the clearance of amyloid-β after ultrasound and microbubble treatment is thought to be mediated in part by microglial activation (Jordão et al. 2013). These findings reiterate the need for carefully controlled treatment exposures to select for desired bio-effects.

Cavitation monitoring and control

It is generally accepted that the behavior of the microbubbles in the ultrasound field is predictive, to an extent, of the observed bio-effects. In the seminal study on the association between cavitation and BBB opening, McDannold et al. (2006) observed an increase in second harmonic emissions in cases of successful opening, compared with exposures that led to no observable changes in permeability as measured by contrast-enhanced MRI. Further, they noted that successful opening could be achieved in the absence of inertial cavitation, which was also reported by another group (Tung et al. 2010). These general guidelines have been central to the development of active treatment control schemes that have been developed to date—all with the common goal of promoting stable bubble oscillations, while avoiding violent bubble collapse that can lead to tissue damage. These methods are based either on detection of sub- or ultraharmonic (O'Reilly and Hynynen 2012; Tsai et al. 2016; Bing et al. 2018), harmonic bubble emissions (Arvanitis et al. 2012; Sun et al. 2017) or a combination thereof (Kamimura et al. 2019). An approach based on the sub-/ultraharmonic controller developed by O'Reilly and Hynynen (2012) has been employed in early clinical testing (Lipsman et al. 2018; Mainprize et al. 2019).

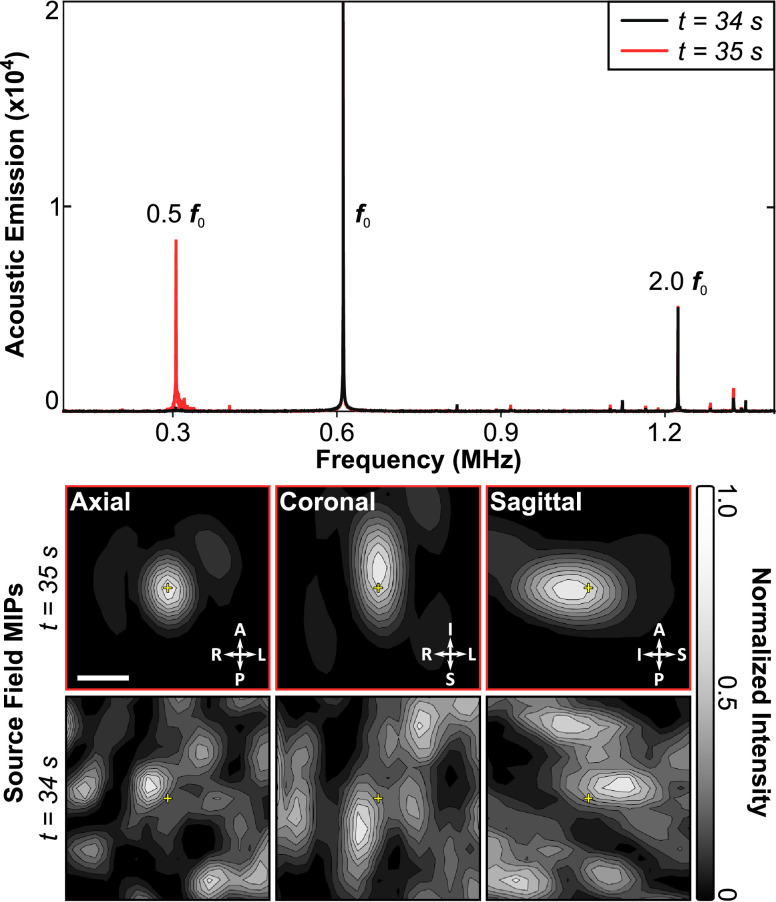

Control methods presented to date have generally been developed using single receiver elements, which simplifies data processing but does not allow signals to be localized. Focused receivers are spatially selective but can miss off-target events, while planar receivers may generate false positives based on signals originating outside the treatment volume. The solution to this is to use an array of receivers and passive beamforming methods, combined with phase correction methods to compensate for the skull bone (Jones et al. 2013, 2015), to generate maps of bubble activity. In the brain this has been achieved with linear arrays (Arvanitis et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2019c), which suffer from poor axial resolution when using passive imaging methods, as well as large-scale sparse hemispherical or large aperture receiver arrays (O'Reilly et al. 2014; Deng et al. 2016; Crake et al. 2018; Jones et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2018a) that optimize spatial resolution for a given frequency. Recently, this has extended beyond just imaging the bubble activity to incorporate real-time, active feedback control based on both the spectral and spatial information obtained from the bubble maps (Jones et al. 2018) (Fig. 4). Robust control methods building on these works will be essential for widespread adoption of this technology to ensure tolerable and consistent treatments.

Fig. 4.

Three-dimensional transcranial subharmonic microbubble imaging and treatment control in vivo in rabbit brain during blood–brain barrier opening. Spectral information (top) indicates the appearance of subharmonic activity at t = 35 s into the treatment. Passive mapping of the subharmonic band localizes this activity to the target region. Bar = 2.5 mm. Reprinted (adapted), with permission, from Jones et al. (2018).

BSCB opening

Despite the similarities between the BBB and BSCB, and the great potential benefit for patients, there has been limited work investigating translation of this technology to the spinal cord. Opening of the BSCB in rats was first reported by Wachsmuth et al. (2009), and was followed by studies from Weber-Adrien et al. (2015), Payne et al. (2017) and O'Reilly et al. (2018) in rats (Fig. 5) and from Montero et al. (2019) in rabbits, the latter performed through a laminectomy window. In 2018, O'Reilly et al. (2018) presented the first evidence of a therapeutic benefit in a disease model, showing improved tumor control in a rat model of leptomeningeal metastases.

Fig. 5.

T1-Weighted sagittal magnetic resonance images revealing leptomeningeal tumors in rat spinal cord (gray arrowhead) before ultrasound and microbubble treatment (left column), and the enhancement of the cord indicating blood–spinal cord barrier opening (white arrows) after ultrasound and microbubble treatment (right column). Reprinted (adapted) with permission from O'Reilly et al. (2018).

Although promising, significant work remains to be done to advance BSCB opening to clinical studies. A more thorough characterization of the bio-effects in the spinal cord and how, if at all, they differ from those in the brain is necessary to ensure safe translation. Additionally, methods and devices capable of delivering controlled therapy to the spinal cord at clinical scale are needed. While laminectomy and implantation of an ultrasound device (Montero et al. 2019) might be an appropriate approach for some focal indications, treating multifocal or diffuse disease will require the ultrasound to be delivered through the intact bone to the narrow spinal canal. Fletcher and O'Reilly (2018) have described a method to suppress standing waves in the human vertebral canal. Combined with devices suited to the spinal geometry, such as that presented by Xu and O'Reilly, (2020), these methods will help to advance clinical translation.

Clinical studies

The feasibility of enhancing BBB permeability in and around brain tumors using ultrasound and microbubbles has now been tested in two clinical trials. In the study conducted at Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris in Paris, France, an unfocused 1-MHz ultrasound transducer (SonoCloud) was surgically placed over the tumor resection area and permanently fixed into the hole in the skull bone. The skin was placed over the transducer, and after healing, treatments were conducted by inserting a needle probe through the skin to provide the driving signal to the transducer. Monthly treatments were then conducted while infusing a chemotherapeutic agent into the bloodstream (carboplatin). The sonication was executed during infusion of SonoVue microbubbles. A constant pulsed sonication was applied during each treatment, followed by a contrast-enhanced MRI to estimate BBB permeability. The power was escalated for each monthly treatment until enhancement was detected on MRI. This study reported the feasibility and tolerability (Carpentier et al. 2016), and a follow-up study may indicate increase in survival (Idbaih et al. 2019).

The second brain tumor study was conducted at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, Canada, which used the InSightec Exablate 220 kHz device and through-skull MRI-guided sonications of brain tumors before the surgical resection. It also described the feasibility of inducing highly localized BBB permeability enhancement and tolerability, and reported that chemotherapeutic concentration in the sonicated peritumor tissue was higher than in the unsonicated tissue (Mainprize et al. 2019).

Another study conducted in Alzheimer's disease patients with the Exablate device reported tolerable BBB permeability enhancement and that the treatment could be repeated 1 mo later without any imaging or behavior indications of adverse events (Lipsman et al. 2018). A third study with the same device investigated the feasibility of using functional MRI to target motor cortex in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients, again finding precisely targeted BBB permeability enhancement without adverse effects in this delicate structure (Abrahao et al. 2019). All of these studies were conducted using Definity microbubbles. These studies have led to the current ongoing brain tumor trial with six monthly treatments of the brain tissue surrounding the resection cavity during the maintenance phase of the treatment with temozolomide. This study sponsored by InSightec is being conducted in multiple institutions. Similarly, a phase II trial in Alzheimer's disease sonicating the hippocampus with the goal of investigating the tolerability and potential benefits from repeated (three treatments with 2-wk interval) BBB permeability enhancement alone is ongoing. This study is also being conducted in several institutions that have the device.

Sonothrombolysis

Occlusion of blood flow through diseased vasculature is caused by thrombi, blood clots that form in the body. Because of limitations in thrombolytic efficacy and speed, sonothrombolysis, ultrasound which accelerates thrombus breakdown alone, or in combination with thrombolytic drugs and/or cavitation nuclei, has been under extensive investigation in the last two decades (Bader et al. 2016). Sonothrombolysis promotes thrombus dissolution for the treatment of stroke (Alexandrov et al. 2004a, 2004b; Molina et al. 2006; Chen et al. 2019), myocardial infarction (Mathias et al. 2016, 2019; Slikkerveer et al. 2019), acute peripheral arterial occlusion (Ebben et al. 2017), deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (Shi et al. 2018) and pulmonary embolism (Dumantepe et al. 2014; Engelberger and Kucher 2014; Lee et al. 2017).

Mechanisms, agents and approaches

Ultrasound improves recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) diffusion into thrombi and augments lysis primarily via acoustic radiation force and streaming (Datta et al. 2006; Prokop et al. 2007; Petit et al. 2015). Additionally, ultrasound increases rt-PA and plasminogen penetration into the thrombus surface and enhances removal of fibrin degradation products via ultrasonic bubble activity, or acoustic cavitation, which induces microstreaming (Elder 1958; Datta et al. 2006; Sutton et al. 2013). Two types of cavitation are correlated with enhanced thrombolysis: stable cavitation, with highly non-linear bubble motion resulting in acoustic emissions at the subharmonic and ultraharmonics of the fundamental frequency (Flynn 1964; Phelps and Leighton 1997; Bader and Holland 2013), and inertial cavitation, with substantial radial bubble growth and rapid collapse generating broadband acoustic emissions (Carstensen and Flynn 1982; Flynn 1982).