Abstract

The development of therapeutic approaches based on direct cardiac reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced-cardiomyocytes (iCM) has emerged as an attractive strategy to repair the injured myocardium. The identification of the mechanisms driving lineage conversion represents a crucial step toward the development of new and more efficient regenerative strategies. To this aim, here we show that pre-treatment with the Bmi1 inhibitor PTC-209 is sufficient to increase the efficiency of Chemical-induced Direct Cardiac Reprogramming both in mouse embryonic fibroblasts and adult cardiac fibroblasts. PTC-209 induces an overall increase of spontaneously beating iCM at end-stage of reprogramming, expressing high levels of late cardiac markers Troponin T and myosin muscle light chain-2v. The inhibition of Bmi1 expression occurring upon PTC-209 pre-treatment was maintained throughout the reprogramming protocol, contributing to a significant gene expression de-regulation. RNA profiling revealed that, upon Bmi1 inhibition a significant down-regulation of genes associated with immune and inflammatory signalling pathways occurred, with repression of different genes involved in interleukin, cytokine and chemokine pathways. Accordingly, we observed the down-regulation of both JAK/STAT3 and MAPK/ERK1-2 pathway activation, highlighting the crucial role of these pathways as a barrier for cardiac reprogramming. These findings have significant implications for the development of new cardiac regenerative therapies.

Subject terms: Regenerative medicine, Reprogramming, Transdifferentiation

Introduction

The adult mammalian heart is unable to fully restore cardiac function after injury, due to the lack of endogenous repair mechanisms1,2. Thus, the development of alternative approaches to regenerate and repair the injured myocardium is considered a top priority in treating heart failure3,4.

Direct cardiac reprogramming (DCR) of fibroblasts into induced CMs (iCMs) has emerged as an attractive strategy. Since the first attempt based on retroviral delivery of the pivotal cardiac transcription factors (TFs) Gata4, Mef2c, and Tbx5 (G-M-T)5, alternative sets of reprogramming factors based on different TFs combinations6,7 or microRNAs8,9, alone or with small chemical compounds capable to inhibit specific signalling pathways or enzymes involved in epigenetic modifications, have been reported4,10.

Recent work11 demonstrated that a solo chemical compound cocktail was able to functionally replace ectopic expression of TFs. The cocktail, comprising six molecules including CHIR99021 (C- a GSK3 inhibitor), RepSox (R- a TGFβR1 inhibitor), Forskolin (F- which sustains cAMP synthesis), Valproic Acid (VPA - a HDAC inhibitor), Parnate (P- an inhibitor of lysine-specific demethylase 1) and TTNPB (T- a highly selective retinoic acid analogue) and thus named CRFVPT, could induce beating clusters of cardiac cells from mouse fibroblasts in vitro11 and in vivo12, although with low efficacy. A similar Chemical-induced Direct Cardiac Reprogramming (CiDCR) has also been reported in human fibroblasts with a combination of nine compounds, in part overlapping the cocktail used to reprogram mouse fibroblasts13.

Although the precise mechanisms underlying CRFVPT activity remain unclear, it can be argued that the two epigenetic modulators Parnate and VPA can help to break through the epigenetic obstacles existing in different cell types, while the two “mesenchymal to epithelial transition” modulators CHIR99021 and RepSox suppress the phenotype of the starting cell. Finally, Forskolin and TTNPB somehow induce the characteristics of the designated cells.

The increase of the efficiency of the reprogramming progress due to the interventions on the epigenetic profile has prompted new strategies to improve the whole process.

Recently, the investigation of epigenetic dynamics accompanying DCR by TFs revealed that H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 undergo an early redistribution at cardiac loci and late alterations at fibroblast loci14, with the subsequent activation of the cardiac program and suppression of the fibroblast phenotype. Similar changes are needed for the induction of cardiac gene expression during the microRNA-induced reprogramming process15. Moreover, the timing of histone methyltransferase inhibition is critical for its effects on reprogramming. In fact, it has been reported that late inhibition of the methyltransferase G9a, responsible for the H3K9me1/2 methylation, increases reprogramming efficiency of fibroblasts16 while pre-treatment with a G9a inhibitor reduced reprogramming efficiency17, demonstrating that specific compound administration is effective only at definite timeframes to increase reprogramming efficiency16. Nevertheless, how the handling of universal epigenetic regulators affects the core gene regulatory network in a specific cell type is still largely unknown. A deeper comprehension of these interactions will allow the identification of appropriate regulators involved in lineage reprogramming.

The identification and modulation of target molecules involved in lineage conversion represents a major challenge5–7. To address this question, Zhou et al. performed a screening for epigenetic regulators with a significant role in iCM generation18 and found that reprogramming efficiency of G-M-T was significantly enhanced by the knockdown of the essential component of the polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1), Bmi1. The silencing of Bmi1 by shRNAs de-repressed the activity of Gata4 during the reprogramming process replacing the need of exogenous Gata4 during the process18. Interestingly, the positive effect provoked by Bmi1 knockdown was confirmed as early as three days after viral transduction and was effective only when the vector was administered early in the iCM reprogramming process18.

Since the use of integrative viruses, frequently adopted in DCR approaches, is related to elevated risks of oncogenesis and genomic disruption, the adoption of a strategy based on the activity of small molecules to induce trans-differentiation via non-genetic strategies provides substantial foundation for pharmacological interventions to be translated into the clinic10.

On this basis, our work aimed at increasing the efficacy of CiDCR by modulating Bmi1 expression with a known inhibitor, PTC-20919. We found that 24 hours pre-treatment with PTC-209 is sufficient to increase the efficiency of CiDCR both in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and adult (5 weeks old) cardiac fibroblasts (CFs). Bmi1 downregulation induced by pre-treatment with 1 μM PTC-209 significantly enhances iCMs generation compared to untreated cells, providing evidences that not only the targeting molecules, but also the timing of inhibition is crucial for its effect on CiDCR efficacy. The expression profile of CFs pre-treated with PTC-209 revealed the down-regulation of chemokines, interleukins and cytokines associated with immune and inflammatory signalling pathways. Accordingly, signalling converging on JAK/STAT3 and MAPK/ERK1-2 activation resulted in compromised reprogramming efficiency. These results could pave the way to the identification of new targeting molecules and novel strategies to booster the current efficiency of CiDCR toward iCM formation.

Results

Pre-treatment with PTC-209 for 24 h enhances CiDCR efficiency of MEFs and adult CFs

Downregulation of the polycomb ring finger oncogene Bmi1 has been identified as a booster in cardiac reprogramming18.

To explore whether CiDCR efficacy could be enhanced by inhibition of Bmi1 expression, we used PTC-209 compound, a recent and well characterized chemical inhibitor of Bmi1, which acts post-transcriptionally by down-regulating Bmi1 protein19.

To define the critical window for Bmi1 inhibition, we started by testing whether the addition of PTC-209 to the CRFVPT cocktail could increase the reprogramming efficacy of MEFs. To this aim, we carried out the reprogramming protocol as previously described11, starting from MEFs isolated from 13.5 dpc embryos of the C57BL strain. Cells were plated on Matrigel pre-coated plates one day before the addition of Cardiac Reprogramming Medium (CRM), containing the small molecule cocktails, plus PTC-209 at different concentrations. At day 16, the medium was changed into Cardiomyocyte Maintaining Medium (CMM) for at least 10 days more. Finally, the reprogramming efficiency of iCM was determined at day 24 by flow cytometry analysis, measuring the percentage of muscle α- myosin heavy chain (α -MHC) positive cells (α-MHC+).

We found that concurrent administration of PTC-209 and CRFVPT cocktail caused a dramatic concentration-dependent decrease in the percentage of α-MHC+ cells upon MEFs reprogramming, with respect to DMSO-treated cells (data not shown).

This prompted us to consider that, being chromatin remodelling a prerequisite to cell fate conversion, the inhibition of Bmi1 expression could be more effective if carried out before the administration of the reprogramming cocktail. On this assumption, we pre-treated MEFs for 24 h with PTC-209, and then cells were treated according to the protocol as depicted in Fig. 1A. Among different doses of PTC-209 tested, we found that pre-treatment with 1 μM PTC-209 reliably enhanced the percentage of α-MHC+ cells at final stage of reprogramming (Fig. 1B,D,F).

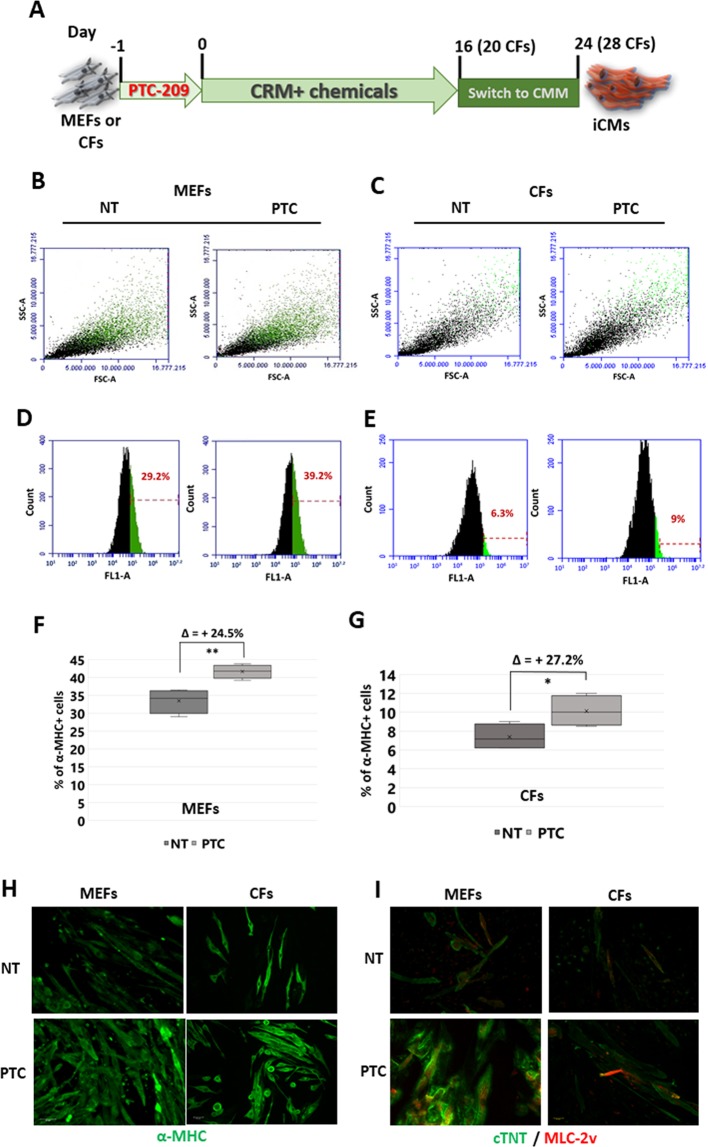

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of direct cardiac reprogramming protocol. MEFs or CFs were plated on Matrigel pre-coated plates in fibroblast growth medium containing 1 μM PTC-209 (PTC) or DMSO (NT) one day before the addition of Cardiac Reprogramming Medium (CRM) containing the small molecule cocktails. At day 16 for MEFs or 20 for CFs, the medium was changed into Cardiomyocyte Maintaining Medium (CMM) for at list 10 days more. Samples were analysed at final stage of reprogramming (day 24 or 28, for MEFs and CFs respectively). (B,C) Representative 2D scatter plots showing end-stage reprogrammed cell population upon 24 h PTC-209 pre-treatment (PTC) or DMSO (NT). Green dots represent α-MHC + cells. Typical results obtained starting from MEFs are in (B); those starting from CFs are in (C). (D,E) Representative plots showing fluorescent cells vs total cell counts, with the percentage of α-MHC + cells highlighted in green, at final stage of reprogramming. The increasing in α-MHC + cells upon PTC-209 pre-treatment is shown in (D) for MEFs and in (E) for CFs. (F,G) Box plots showing the percentage of α-MHC + cells, normalized to cell count, at final stage of reprogramming from MEFs (F) or CFs (G). For each data set: n = 4; Δ = mean of % of α-MHC + cell increase upon 24 h PTC-209 pre-treatment. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (H) Representative immunostaining of cardiac marker α-MHC (green). (I) Representative immunostaining of cardiac markers MLC-2v (red) and cTNT (green). Images are related to different areas of beating clusters of iCMs at end-stage of reprogramming from MEFs and from CFs. Scale bars: 40 μM.

Considering that CFs are the major in vivo target for iCM reprogramming, we next determined the effect of PTC-209 pre-treatment on the conversion of adult (5 weeks) CFs to iCMs. Flow cytometry results indicated that the overall conversion efficiency induced by CiDCR was lower than that observed in MEFs. Nevertheless, 24 h pre-treatment with 1 μM PTC-209 was able to increase (up to 27%) the efficiency of reprogramming also of CFs (Fig. 1C,E,G).

Immunostaining revealed that iCMs derived from both MEFs or CFs were not only positive for α-MHC (Fig. 1H), but also exhibited high expression of late cardiac markers troponin-T (cTNT) and myosin light chain-2v (MLC-2v), with a clear cross-striated pattern (Fig. 1I).

Quantitative RT-PCR confirmed the expression of cardiac-specific markers, such as cTNT, Gata4, Hcn4, Myh-7b, Mef2c, Mlc-2v, Nkx2.5, Ryr2, Tbx5 and SercA4 (Supplementary Fig. S1-A and S1-B). Moreover, an increase in the number of beating clusters could be observed in pre-treated cells with respect to the NT counterpart (Supplementary Fig. S1-C). In line with these data, the percentage of α-actinin positive cells with assembled sarcomeres also increased upon PTC-209 treatment (Supplementary Fig. S1-D,E). Representative videos showing beatings areas, as well as immunostaining of isolated MEFs and CFs for fibroblast and endothelial markers are showed in Supplementary Data (Movies S1 and S2 and Supplementary Fig. S2).

These data demonstrate that 24 h pharmacological inhibition of Bmi1 is sufficient to significantly increase the efficiency of CiDCR of both MEFs and CFs, thus confirming that Bmi1 may act as an early barrier to DCR. Nevertheless, quantification of absolute number of cardiac-marker-positive iCMs at the end stage of reprogramming revealed that CiDCR efficiency varied depending on cell type assayed, suggesting intrinsic variability that should be considered to further improve the CRFVPT cocktail.

Effects of PTC-209 pre-treatment on Bmi1 expression last throughout the reprogramming

Considering that 24 h pre-treatment with PTC-209 was sufficient to enhance the efficiency of CiDCR, we investigated the persistence of PTC-209 effects beyond the time of compound administration, throughout the whole reprogramming protocol.

To this aim, we analysed the expression profile of Bmi1 in pre-treated MEFs undergoing CiDCR, in comparison to untreated cells. As expected, 24 h PTC-209 treatment induced Bmi1 down-regulation at protein levels (Fig. 2A, T0). Interestingly, this effect persisted after PTC-209 removal, coinciding with first days of CRFVPT administration (Fig. 2A, T4).

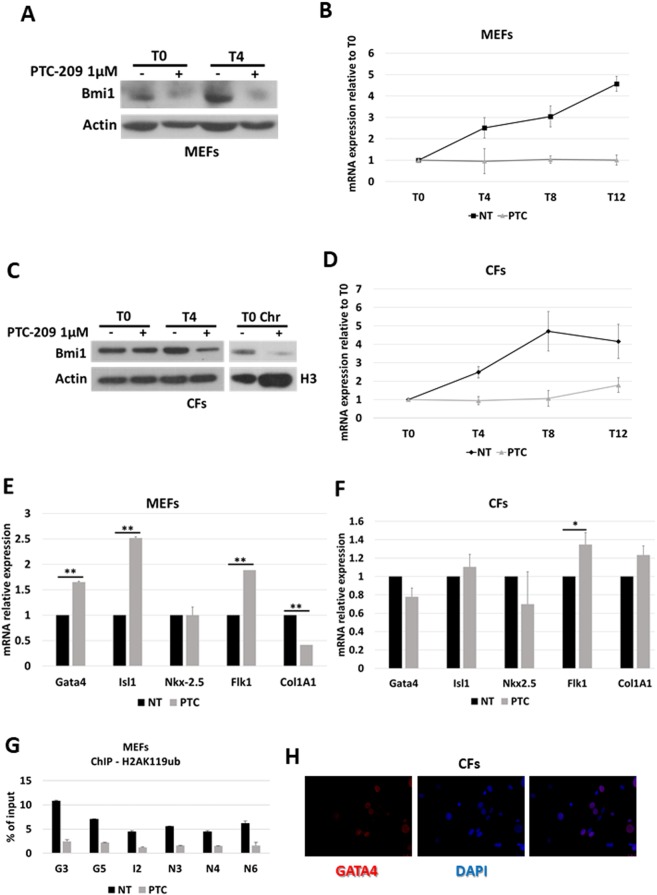

Figure 2.

(A,C) Bmi1 expression profile by Western blot upon CiDCR of MEFs (A) or CFs (C) pre-treated for 24 h with 1 μM PTC-209 (PTC) or DMSO (NT), at indicated days. betaActin was used as the loading control. Panel C also shows Bmi1 protein levels in the chromatin fraction (Chr) of CFs at T0, upon PTC-209 pre-treatment. Histone H3 was used as loading control. White spaces between blots indicate that they were grouped from different gels or fields. ( B,D) Bmi1 expression profile by quantitative RT PCR on MEFs (B) or CFs (D) undergoing CiDCR with or without 24 h PTC-209 pre-treatment. For each data set, averaged numbers from biological triplicates were used for statistics. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. (E,F) Expression profile of Bmi1 target genes and cardiac marker genes by quantitative RT PCR on MEFs (E) or CFs (F) upon 24 h 1 μM PTC-209 pre-treatment. For each data set, averaged numbers from biological triplicates were used for statistics. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (G) ChIP-qPCR for H2AK119ub on MEFs at Gata4 (G3 and G5), Isl1 (I2) and Nkx2-5 (N3, N4 and N6) cardiac loci. Averaged numbers from technical duplicates were used for statistics. (H) Representative immunostaining of Gata4 on CFs. Scale bars: 40 μM.

The analysis of Bmi1 expression in CFs upon PTC-209 pre-treatment showed similar results (Fig. 2C), although the downregulation of Bmi1 at T0 was not always evident in total extract. Nevertheless, immunoblot assay on fractionated cell extracts demonstrated that, upon PTC-209 pre-treatment, the amount of Bmi1 present in the fraction of proteins bound to chromatin drastically decreased (Fig. 2C).

Quantitative RT PCR analysis demonstrated that, indeed, PTC-209 pre-treatment has clear effects on Bmi1 expression throughout CiDCR of both MEFs (Fig. 2B) and CFs (Fig. 2D), counteracting the spontaneous up-regulation of Bmi1 mRNA observed in DMSO-treated cells. Of note, the increasing in Bmi1 expression upon CiDCR might indicate a possible role of PRC1 in governing molecular events in later phases of CiDCR.

These results demonstrated that the inhibition of Bmi1 expression occurring within 24 h pre-treatment with PTC-209 in both MEFs and CFs perdures after compound withdrawal. This probably causes an epigenetic perturbation, whose effects contribute to improve cellular response to CRFVPT cocktail.

Based on the data from Zhou and colleagues18, we wondered whether a 24 h inhibition of Bmi1 expression could be sufficient to modulate chromatin status and expression of a set of critical cardiogenic factors, including Gata4, Isl1 and Nkx2.5 or other cardiogenic markers.

As shown in Fig. 2E, the exposure of MEFs to PTC-209 induces the up-regulation of Bmi1 target genes Gata4 and Isl1, together with the increase of Flk1 expression, which is marker of cardiovascular precursor cells. Nkx2.5 expression, on the contrary, didn’t show significant modifications in agreement with previous results18. The increase of cardiac markers was accompanied by a concomitant down-regulation of the fibroblast marker gene Collagen 1A1 (Col1A1). ChIP qPCR of monoubiquitylation of histone H2A at lysine 119 (H2AK119ub) on cardiogenic loci demonstrated that, upon PTC-209 pre-treatment, the repressive histone mark was significantly reduced (Fig. 2G), in line with previous reports18. These data confirmed that in MEFs Bmi1 acts as a repressor of cardiogenic loci and its inhibition is responsible for their transcriptional activation. However, when we analysed the expression profile of cardiac markers in pre-treated CFs, we couldn’t detect the same stimulation of gene expression (Fig. 2F), as no Gata4 nor Isl1 upregulation was achieved by PTC-209 treatment. It is also important to note that Gata4 seems to be already expressed, even though at low levels, in CFs (Fig. 2H), indicating that the epigenetic status of this and probably other loci might be profoundly different between the two cell types analysed.

This prompted us to investigate the mechanisms underlying the pro-reprogramming activity of Bmi1 inhibition in CFs by addressing the PTC-209-dependent transcriptional effects.

PTC-209 pre-treatment modulates signalling pathways governing cell fate conversion

Modifications of signalling pathways and environmental cues are expected to improve the efficiency of DCR and cardiac cell maturation. Indeed, numerous reports demonstrated the improvement of reprogramming by GMT via addition of small molecule that influence different pathways10.

Being Bmi1 an epigenetic modulator, its inhibition, albeit transitory, could trigger a significant perturbation of chromatin status, thus making the cell prone to trans-differentiation.

To identify the downstream targets of PTC-209 in CFs, we performed RNA-sequencing analyses of cells untreated (DMSO) or treated with 1 μM PTC-209 for 24 h and selected the most significant differentially expressed genes (DEGs).

Volcano plot in Fig. 3A shows the results of DEseq 2 bioinformatics analysis, which revealed 1,499 genes (569 up-regulated and 930 down-regulated, with pAdj ≤ 0.05) that were differentially expressed with a Fold Change (FC) ≥ 2 upon PTC-209 treatment. Table 1 reports the top 50 genes in both categories (see Supplementary Table S1 for complete gene list).

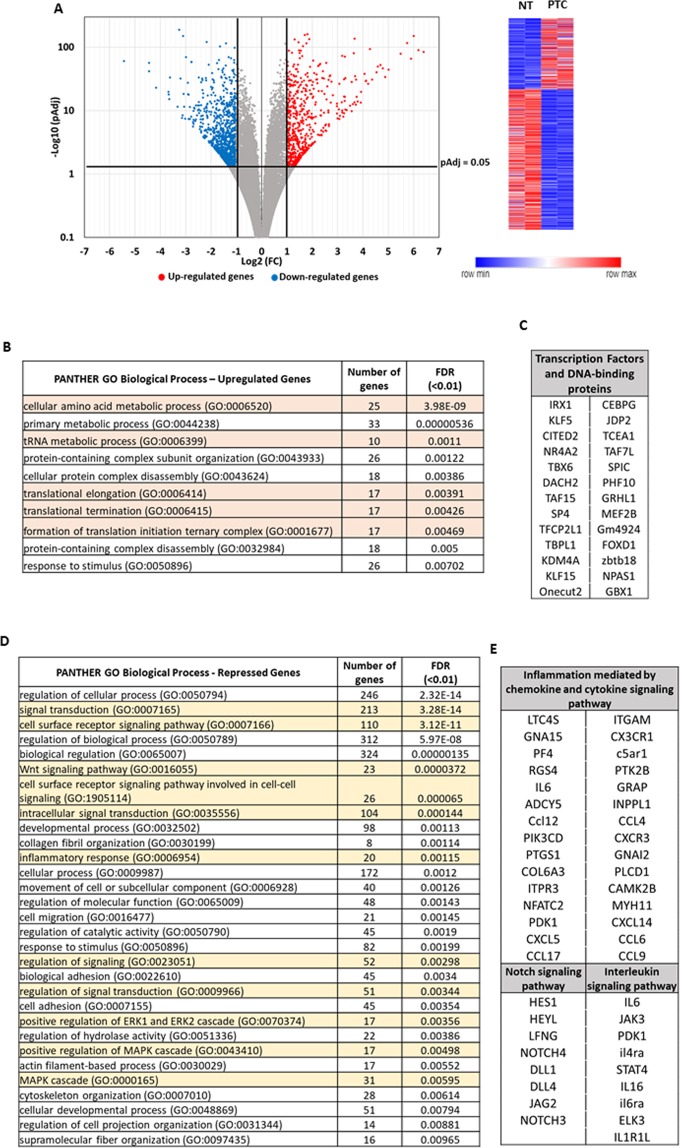

Figure 3.

DEGs identified by RNA-seq assay in CFs pre-treated with 1 μM PTC-209 (PTC) vs DMSO (NT) cells. (A) Volcano plot and relative heatmap. The negative log of pAdj (base 10) is plotted on the Y-axis, and the log of the FC (base 2) is plotted on the X-axis. Red plots represent significant (pAdj < 0.05) and remarkable (FC > 2) up-regulated genes, while blue plots represent significant (pAdj > 0.05) and remarkable (FC < 2) downregulated genes. (B) Functional enrichment analysis of de-repressed genes for significantly over-represented Biological Process (FDR < 0.01). Highlighted in orange are the GO terms related to protein biosynthesis. (C) Significantly de-repressed Transcription Factors and DNA-binding proteins. (D) Functional enrichment analysis of repressed genes for significantly over-represented Biological Process (FDR < 0.01). Highlighted in yellow are the GO terms related to signal transduction. (E) Repressed genes belonging to Notch, Interleukin and inflammatory pathway, according to KEGG analysis. DEG, differentially expressed gene; FC, fold change.

Table 1.

Top 50 DEGs (pAdj < 0.05).

| GeneSymbol | log2 | GeneSymbol | log2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gm19410 | 6.39 | GJB3 | -5.44 |

| EXTL1 | 6.19 | PPL | -4.44 |

| CTH | 6.00 | GJB5 | -4.44 |

| TENM4 | 5.90 | GJB4 | -4.17 |

| Car6 | 5.74 | Ms4a6b | -3.68 |

| CYB5R2 | 5.49 | KIF26B | -3.67 |

| COX6A2 | 5.01 | aldh3a1 | -3.65 |

| TNFRSF19 | 4.87 | TNS4 | -3.62 |

| SH2D6 | 4.78 | C1QA | -3.32 |

| adm2 | 4.69 | LRRN4 | -3.26 |

| SOAT2 | 4.59 | CDC42EP2 | -3.21 |

| RAB39B | 4.54 | Ccl12 | -3.15 |

| NRIP2 | 4.35 | AF357359 | -3.12 |

| TRIB3 | 4.28 | Rian | -3.11 |

| TRIM66 | 4.21 | NREP | -3.08 |

| SLC7A3 | 4.12 | MS4A4A | -3.06 |

| ANGPTL6 | 4.11 | AIF1 | -3.01 |

| PPEF1 | 4.06 | CKB | -2.99 |

| PDZD7 | 3.93 | NPR3 | -2.92 |

| DTHD1 | 3.92 | AKAP5 | -2.90 |

| MEI4 | 3.79 | CD52 | -2.89 |

| ADTRP | 3.75 | CD248 | -2.88 |

| PPP1R16B | 3.72 | RAB3IL1 | -2.84 |

| 1700019D03Rik | 3.72 | C1QB | -2.83 |

| P2RX3 | 3.69 | C1QC | -2.78 |

| ACOT2 | 3.67 | meg3 | -2.77 |

| ELOVL3 | 3.66 | SLCO4A1 | -2.77 |

| AVIL | 3.64 | TMEM119 | -2.71 |

| SLC4A10 | 3.61 | Nxpe5 | -2.71 |

| SLC7A11 | 3.56 | CD72 | -2.70 |

| CDH22 | 3.55 | AQP5 | -2.69 |

| F5 | 3.35 | SYNPO | -2.69 |

| SLC6A9 | 3.30 | Gm20744 | -2.68 |

| MEF2B | 3.30 | wisp2 | -2.67 |

| ADRA2A | 3.29 | ATP2B4 | -2.65 |

| CHAC1 | 3.28 | LRRN2 | -2.63 |

| KCNMA1 | 3.27 | CLDN15 | -2.59 |

| CATSPERD | 3.26 | EMILIN1 | -2.59 |

| Gbp8 | 3.26 | cys1 | -2.55 |

| SLC7A5 | 3.25 | CHST1 | -2.52 |

| TAF7L | 3.23 | FRMPD1 | -2.51 |

| PSPH | 3.19 | Kctd12b | -2.48 |

| OTUD7A | 3.18 | TUBB4A | -2.48 |

| PRR32 | 3.18 | SMPD3 | -2.48 |

| dnah14 | 3.16 | GPR153 | -2.47 |

| OSTN | 3.09 | Ms4a6c | -2.47 |

| GADD45A | 3.07 | IGFBP4 | -2.44 |

| Akr1b7 | 3.06 | GPR34 | -2.44 |

| GBX1 | 3.05 | PEG10 | -2.43 |

| FGF21 | 3.00 | EPS8L2 | -2.42 |

| LRRN3 | 2.98 | MRC1 | -2.41 |

| 1810010H24Rik | 2.97 | CCK | -2.40 |

| B4GALNT2 | 2.97 | VDR | -2.40 |

We used the PANTHER database to perform functional classification analysis. DEGs were initially grouped according to the PANTHER Protein Classification and results showed that the most represented protein categories among de-repressed genes were somehow involved in protein biosynthesis (Table 2). Accordingly, the PANTHER GO-Biological Process analysis showed a significant (FDR < 0.01) enrichment of processes related to both amino acids and protein metabolism (Fig. 3B, orange lines). Moreover, physical and functional interactions between de-repressed genes, determined by using the STRING platform with a highest confidence score of 0.9, revealed three main clusters which were representative of the three KEGG pathway: “Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis”, “Biosynthesis of amino acids” and “Ribosome biogenesis” (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Table 2.

PANTHER Protein Classes Most Represented in CFs pre-treated with 1 μM PTC-209 (pValue and FDR < 0.05).

| PANTHER Protein Class | PANTHER ID | Type of regulation (+/−) | pValue | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| oxidoreductase | PC00176 | + | 0.000044 | 0.00315 |

| methyltransferase | PC00155 | + | 0.0000805 | 0.0173 |

| aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase | PC00047 | + | 0.000087 | 0.00932 |

| oxidase | PC00175 | + | 0.000193 | 0.00831 |

| cytoskeletal protein | PC00085 | − | 0.00000016 | 0.00000857 |

| nucleic acid binding | PC00171 | − | 0.0000002 | 0.00000861 |

| G-protein modulator | PC00022 | − | 0.000000241 | 0.00000865 |

| defence/immunity protein | PC00090 | − | 0.000000454 | 0.0000122 |

| enzyme modulator | PC00095 | − | 0.0000016 | 0.0000376 |

| glycosyltransferase | PC00111 | − | 0.000024 | 0.000471 |

| signalling molecule | PC00207 | − | 0.000609 | 0.00818 |

| cytokine | PC00083 | − | 0.00075 | 0.00896 |

| microtubule family cytoskeletal protein | PC00157 | − | 0.00137 | 0.0128 |

| chemokine | PC00074 | − | 0.0019 | 0.0141 |

| receptor | PC00197 | − | 0.00235 | 0.0168 |

| extracellular matrix protein | PC00102 | − | 0.00611 | 0.0398 |

Interestingly, among de-repressed genes there were also 26 transcription factors or DNA-binding proteins (Fig. 3C), some of which playing pivotal roles in heart development. As the case of Iroquois homeobox gene 1 (Irx1), encoding a cardiac transcription factor important for the development of ventricular conduction system20; Krüppel-like factor 5 (Klf5), a zinc finger-containing transcription factor involved in many different cellular processes, ranging from the governance of pluripotency of embryonic stem cell to regulation of cardiovascular pathophysiology21–23; the transcriptional modulator Cited2, involved in Brachyury, Mesp1, Isl1, Gata4 and Tbx5 expression during cardiac differentiation of embryonic stem cells24; Nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 (NR4A2), also known as Nurr1, a member of the NR4A orphan nucleus receptor family involved in the immediate early response to different stress-stimuli, with some roles in cardiac remodelling25; Tbx6, a member of the evolutionarily conserved T-box family of transcription factors that are essential regulators of normal embryonic development, critical for mesoderm induction and subsequent lineage diversification by regulation of Nkx2-5 expression26; JMJD2A/KDM4A, a member of the JmjC domain–containing family JMJD2 of histone demethylases that catalyse the demethylation of trimethylated H3K9 (H3K9me3) and H3K36 (H3K36me3), involved in promotion of cardiac hypertrophy27, as well as the c-Jun dimerization protein 2, JDP2, member of the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) superfamily which typically suppresses transcription through binding to CRE and TRE DNA promoter elements and recruiting histone deacetylases28; Rp58 (also known Znf238, Zfp238, Zbtb18), a sequence-specific transcriptional repressor which inhibits Id genes (Id1-4) playing a central and evolutionarily conserved role during muscle formation29; the ubiquitous protein PHF10, a subunit of the PBAF chromatin-remodelling complexes which plays crucial role in antagonizing Polycomb action during development30; the forkhead box transcription factors Foxd1, which has been recently described as a promoter of iPSC generation31; the myocyte-specific enhancer factor MEF2b32.

Concerning repressed genes, they not only represent the largest group in our data set, but are also composed of heterogeneous protein subtypes. They can be grouped in a wide spectrum of protein classes involved in a broad array of processes (Table 2). Nevertheless, many targets down-regulated upon Bmi1 inhibition are involved in cell signalling. Indeed, according to the PANTHER classification, GO Biological Processes analysis revealed that many genes downregulated upon PTC-209 pre-treatment play some roles in signal transduction (Fig. 3D, yellow lines). KEGG pathway analysis in Table 3 suggests that different signal transduction pathways might be de-regulated upon Bmi1 inhibition. Many genes, indeed, seems to be involved in Wnt, Hippo, Rap1, PI3K/AKT, cAMP and calcium-dependent signalling pathways. Interestingly, 8 genes belong to the Notch pathway (Fig. 3E), which has been previously identified as down-regulated upon PTC-209 pre-treatment in leukaemia cells33. Moreover, we found 30 genes involved in chemokine and cytokine signalling pathways and 9 genes specific of interleukins pathway (Fig. 3E).

Table 3.

Significantly enriched KEGG pathways (p < 0.05) – downregulated genes.

| KEGG ID | Pathway Description | Genes | pValue |

|---|---|---|---|

| mmu04512 | ECM-receptor interaction | 14 | 0.0003 |

| mmu04360 | Axon guidance | 17 | 0.0004 |

| mmu04540 | Gap junction | 13 | 0.0008 |

| mmu04310 | Wnt signaling pathway | 17 | 0.0012 |

| mmu04611 | Platelet activation | 16 | 0.0015 |

| mmu00532 | Glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis - chondroitin sulfate / dermatan sulfate | 6 | 0.0022 |

| mmu04390 | Hippo signaling pathway | 17 | 0.0024 |

| mmu05150 | Staphylococcus aureus infection | 9 | 0.0025 |

| mmu04020 | Calcium signaling pathway | 19 | 0.0026 |

| mmu04550 | Signaling pathways regulating pluripotency of stem cells | 16 | 0.0026 |

| mmu04015 | Rap1 signaling pathway | 21 | 0.0034 |

| mmu05217 | Basal cell carcinoma | 9 | 0.0040 |

| mmu05412 | Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) | 10 | 0.0046 |

| mmu00533 | Glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis - keratan sulfate | 5 | 0.0048 |

| mmu04924 | Renin secretion | 10 | 0.0068 |

| mmu04713 | Circadian entrainment | 12 | 0.0073 |

| mmu04916 | Melanogenesis | 12 | 0.0079 |

| mmu04330 | Notch signaling pathway | 8 | 0.0086 |

| mmu05205 | Proteoglycans in cancer | 19 | 0.0090 |

| mmu05146 | Amoebiasis | 13 | 0.0105 |

| mmu04151 | PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | 28 | 0.0106 |

| mmu04510 | Focal adhesion | 19 | 0.0109 |

| mmu04670 | Leukocyte transendothelial migration | 13 | 0.0112 |

| mmu04514 | Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) | 16 | 0.0113 |

| mmu04062 | Chemokine signaling pathway | 18 | 0.0135 |

| mmu04024 | cAMP signaling pathway | 18 | 0.0142 |

| mmu05200 | Pathways in cancer | 30 | 0.0151 |

| mmu01100 | Metabolic pathways | 78 | 0.0161 |

| mmu05414 | Dilated cardiomyopathy | 10 | 0.0180 |

| mmu04060 | Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 20 | 0.0244 |

| mmu05166 | HTLV-I infection | 22 | 0.0253 |

| mmu04974 | Protein digestion and absorption | 10 | 0.0254 |

| mmu05133 | Pertussis | 9 | 0.0255 |

| mmu04610 | Complement and coagulation cascades | 9 | 0.0293 |

| mmu04970 | Salivary secretion | 9 | 0.0314 |

| mmu00604 | Glycosphingolipid biosynthesis - ganglio series | 4 | 0.0329 |

| mmu05410 | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) | 9 | 0.0359 |

| mmu04261 | Adrenergic signaling in cardiomyocytes | 13 | 0.0411 |

These subsets of genes attracted our attention, because down-regulation of inflammatory signalling has been recently related to increasing reprogramming efficiency. Muraoka et al., indeed, demonstrated that diclofenac sodium treatment greatly enhanced GMT-dependent cardiac reprogramming in postnatal and adult fibroblasts, but not in MEFs, via the inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 /prostaglandin E2/PGE receptor 4/interleukin 1β/interleukin 1 receptor type 1 signalling and subsequent suppression of inflammatory and fibroblast gene programs34. Previous report also identified ZNF281 transcription factor as a robust and efficient activator of adult DCR through its association with Gata4 by inhibiting inflammatory signalling35. Moreover, there is growing evidence that innate immunity is a crucial regulator of tissue healing in neonatal hearts36. Indeed, a very recent paper demonstrate that CD4 + regulatory T-cells promote neonatal heart regeneration through the releasing of paracrine regenerative factors37.

On these bases, we performed qPCR experiment which confirmed the results of RNA-seq for the most relevant down-regulated cytokines (Supplementary Fig. S4). We also checked for the expression of other relevant cytokines and their cognate receptors which have been demonstrated to play a direct role in regulation of neonatal cardiomyocyte proliferation. Results indicate that these cytokines are not expressed in our cells (IFNγ, IFNβ, IL10) or are unmodified upon the treatment (IL1b, TNFRS1A, IFNAR1). Only in the case of TNFα a slight increase was observed that however did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Fig. S4).

All these data prompted us to investigate whether Bmi1 inhibition could lead to a decreasing in pro-inflammatory pathway activation.

PTC-209 pre-treatment lowers the levels of activated STAT3 and ERK1 in CFs

Down-regulation of different cytokine, chemokine and interleukin receptors, as well as of their pathway mediators, suggested us that these proteins could be at least in part responsible for the enhancement of reprogramming efficiency.

The signal transduction via type I and II cytokine receptors is based on JAKs, which in turn activates the STATs family of transcription factors, resulting in their phosphorylation and subsequent nuclear translocation38,39. RNA-seq clearly showed the down-regulation of different members of IL6 signalling pathway, which usually exerts its function through the activation of JAK/STAT3.

The possibility that STAT signalling could be downregulated as a secondary effect of PTC-209 activity was newsworthy, considering that the rate of DCR was increased by addition of JAK inhibitors to a combination of miRNAs 1, 133, 208, and 4998.

On these bases, we decided to assess the activation and subcellular localization of STAT3 in both MEFs and CFs upon 24 h PTC-209 pre-treatment.

As shown in Fig. 4, STAT3 total expression (FT fractions) seems to be only mildly affected by PTC-209 treatment in both MEFs (Fig. 4A) or CFs (Fig. 4B). This is in line with RNA-seq data, which didn’t show any direct modification in STAT3 gene expression. However, looking at STAT3 phosphorylation and subcellular localization it is glaring that both total (FT) and nuclear (N) fractions show a dramatic decrease of activated STAT3, suggesting a down-regulation of the pathway.

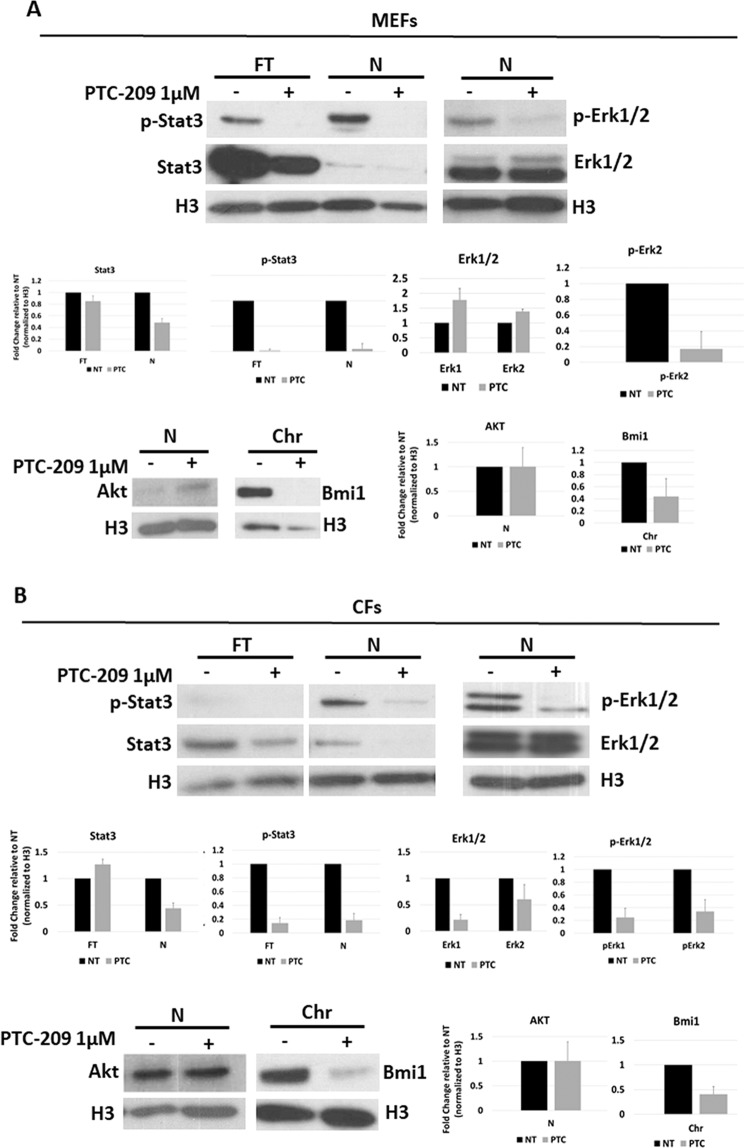

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis showing p-STAT3, STAT3, p-ERK1/2, ERK1/2 and AKT expression in MEFs (A) or CFs (B) upon treatment with 1 μM PTC-209 for 24 h (PTC), compared to DMSO-treated (NT) cells. Histone H3 was used as loading control. Cells were fractioned into total (FT), total nuclear (N), and chromatin (Chr) fractions. Equal amounts of each fraction were loaded to allow for comparison of band intensity. Graphs report densitometric analysis of western blot on p-STAT3, STAT3, p-ERK1/2, ERK1/2, Bmi1 and AKT proteins normalized to the level of H3 loading control. Densitometric analysis of the bands was carried out using Image Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics Inc. Rockville, MD, USA). Intensity of bands from the protein of interest were normalized to the intensity of H3 bands of the respective blots. Data are presented as means ± SD of the densitometric analysis of n = 2 blots.

Apart from JAK/STATs, the binding of cytokines to their specific receptors may induce the activation of other signalling pathways, including the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathways40,41.

As shown in Fig. 4B, while AKT expression was unaffected, CFs showed a dramatic decrease of phosphorylated ERK1/2 upon Bmi1 inhibition, with ERK1 activation being more affected than ERK2. Interestingly, MEFs showed a downregulation of activated ERK2 upon 24 h PTC-209 treatment. On the contrary, AKT appeared mildly activated by PTC-209.

These data sustain the hypothesis that Bmi1 inhibition promotes CiDCR of CFs by repressing inflammatory pathways.

Discussion

To achieve the full potential for DCR without the use of transgenes and to project cardiac reprogramming to a preclinical stage, a deeper knowledge of signalling networks that determine cell fate conversion is required to select new combinations of small molecules capable of governing CiDCR in a more efficient way42.

In this study we report that 24 h pharmacological inhibition of Bmi1 by 1 μM PTC-209 increases the conversion of MEFs and CFs into iCM, promoting cardiac gene expression and spontaneous beatings. Although PTC-209 was removed at the time of CRFVPT cocktail administration to the cells, it is likely that the epigenetic perturbation induced by Bmi1 inhibition is sufficient to imprint some changes in gene expression, capable to improve the effect of reprogramming cocktail. On the contrary, we found that the addition of PTC-209 for the entire reprogramming protocol resulted in a dramatic decrease in CiDCR efficacy. Probably, prolonged and powerful inhibition of Bmi1 expression could represent a barrier to the effect of CRFVPT cocktail, possibly due to some roles exerted by Bmi1 in cells undergoing trans-differentiation in later phases of reprogramming. Indeed, Bmi1 expression levels increase during CiDCR, supporting such hypothesis. Bmi1 was previously found necessary for reprogramming iPSC43, and Bmi1 expression is one of the shared features of many adult stem cell compartments44. It is thus logical to hypothesize that Bmi1 expression might be relevant for maintaining some precursor cells arising during trans-differentiation.

As PTC-209 downregulates the Bmi1 protein levels, it should faithfully recapitulate the effect of Bmi1 downregulation. Indeed, our data obtained in MEFs confirmed previous reports18 indicating that Bmi1 acts as an epigenetic barrier to DCR in MEFs by repressing cardiogenic loci, as Gata4 and Isl1. These events occurred together with the induction of other cardiac precursor marker genes, such as Flk1 and the down-regulation of fibroblast marker genes, such as Col1A1.

However, despite an overall improvement of CiDCR, some differences were observed between MEFs and CFs in their response to PTC-209, like no changes in cardiogenic genes in CFs upon PTC-209 administration. These prompted us to address the transcriptional effects of PTC-209 on CFs by RNA-sequence profiling and to relate them to its pro-reprogramming activity. Bioinformatic analysis of de-repressed genes showed a significant enrichment in genes involved in different steps of protein biosynthesis. This suggests that PTC-209 treatment at the dose of 1 μM, does not inhibit, rather promote active cell metabolism. After all, our data set didn’t show a significant up-regulation of the Bmi1 downstream effectors p16Ink4a, p19Arf and p53, which mediate Bmi1-dependent regulation of cell proliferation and senescence45. Rather, among de-repressed genes we found transcription factors playing different role in cardiovascular tissue development and cardiac differentiation.

Repressed genes, on the other hand, represent a large group of proteins mostly implicated in signal transduction pathways, whose inhibition has been suggested to be a booster for cardiac trans-differentiation, such as Wnt10, Hippo46, cAMP and calcium-dependent signalling pathways34 and Notch47. The eight genes belonging to the Notch pathway represent also an internal control, as it has been previously described that this pathway is down-regulated upon PTC-209 treatment in leukaemia cells33. Interestingly, Olson and colleagues showed that Notch inhibition and Akt1 activation in a cooperative manner boosted the efficiency of reprogramming of MEFs by GHMT factors up to 70%, while 45% of the generated cardiomyocytes showed spontaneous beating47.

It is well demonstrated that the silencing of fibroblast signatures is a prerequisite for reprogramming17,48. In the same line of reasoning, anti-inflammation may represent a potential target for lineage conversions associated with aging, as in case of heart regeneration upon MI49. Indeed, we found an overall repression of receptors and intracellular mediators of inflammation and immune response, which usually exert their function by induction of pro-inflammatory responses dependent on JAK/STAT3 and ERK1/2 activation.

This is of great interest, considering that reprogramming toward induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) by overexpressing Yamanaka factors can be shifted toward cardiogenesis in the presence of a JAK inhibitor and cardiomyocyte-favourable culture condition50, and that the addition of JAK I inhibitor enhances miRNA-mediated reprogramming by 10-fold8.

Our results demonstrated that upon Bmi1 inhibition in CFs, a dramatic downregulation of both STAT3 and ERK1 nuclear translocation occurred. Of notes, the use of ERK1 inhibitors, in combination with other 8 different compounds in part overlapping CRFVPT cocktails, has been demonstrated to increase the yield of iCMs from human fibroblasts13.

A very recent paper described the ability of a combination of four chemicals, named IMAP, consisting of Insulin-like growth factor-1, Mll1 inhibitor MM589, transforming growth factor-β inhibitor A83-01, and PTC-209, to increase the rate of GMT-induced cardiac reprogramming by suppressing specific C-C chemokine signalling pathways51. These results and our findings strongly indicate that fibroblast trans-differentiation into cardiomyocytes, either obtained by transducing transcription factors or by chemical compounds, is highly enhanced by suppressing inflammatory pathways.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate for the first time that CRFVPT cocktail efficacy can be increased by 24 h pharmacological inhibition of the epigenetic modulator Bmi1, whose sole repression is sufficient to enhance CiDCR from both MEFs and CFs. We confirmed that in MEFs Bmi1 repression resulted in a major loss of H2AK119ub at specific cardiac loci, with the consequent de-repression of cardiogenic genes expression. In CFs the inhibition of Bmi1 expression correlate with repression of two major pathways related to inflammation, such as JAK/STAT3 and MAPK/ERK1/2. This is in line with previous reports indicating that inflammation and fibrosis, with their related genes, highly expressed in postnatal and adult fibroblasts compared with embryonic fibroblasts, represent age-related barriers to cardiac reprogramming35.

Our results may contribute to a deeper knowledge of signalling networks that determine cell fate, laying the foundations to set up new combinations of small molecules capable of governing DCR in a more efficient way.

These findings might have significant implications for the advance of new cardiac regeneration therapies.

Methods

Animals

All animal procedures were performed with the approval of O.P.B.A. of University of Naples Federico II. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Cell culture

MEFs were isolated from embryonic day 13.5 (E13.5) C57BL/6 mouse embryos. The head, limbs, and internal organs were carefully removed from embryos, and then the rest tissues were washed in PBS, minced and digested with 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA into single-cell suspensions. Cells were resuspended in fibroblasts medium, consisting of DMEM (Gibco), 15% FBS (Hyclone), 2 mM Glutamax (Gibco), 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids (NEAA; Gibco), 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco), and plated onto one 10 cm dish per embryo. Cells were passaged at the ratio of 1:3 (passage 1). Passage 3 MEFs were used for reprogramming

CFs were isolated from 4–6 weeks old C57BL/6 mice. Briefly, heart tissue was isolated, washed in PBS, minced and digested with a solution containing type II collagenase (3 mg/ml) and BSA (10 mg/ml) up to 45 minutes at 37 °C. CFs from three hearts were plated onto a 10 cm dish with fibroblast growth medium. Passage 1 CFs were used for reprogramming.

Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into iCM

The protocol of DCR was similar to previous studies with minor optimization11. MEFs or CFs were seeded onto six-well plates (coated with 1:100 Matrigel from BD Biosciences for 1 h at room temperature) at a density of 50 000 cells per well and cultured in fibroblast growth medium for 24 h. For PTC pre-treated samples, 1 μM PTC-209 (Sigma) was added to fibroblasts medium for 24 h. For NT samples, equal amount of DMSO was added.

After 24 h, the medium was replaced with CRM, composed of knockout DMEM (Gibco), 15% FBS, and 5% KSR (Gibco), 0.5% N2 (Gibco), 2% B27 (Gibco), 1% Glutamax, 1% NEAA, 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Gibco), 50 μg/ml 2-phospho-L-ascorbic acid (vitamin C, Sigma), 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, plus CRFVPT cocktails (10 μM CHIR99021 (C, Sigma); 10 μM RepSox (R, Selleckchem); 50 μM Forskolin (F, Selleckchem); 0.5 mM VPA (V, Sigma); 5 μM Parnate, (P, Selleckchem); 1 μM TTNPB (T, Selleckchem). CRM containing chemical compounds was changed every 4 days. At the second stage of induction (day 16 for MEFs, day 20 for CFs), cells were cultured in CMM (DMEM medium with 15% FBS, 2i (3 μM CHIR99021 and 1 μM PD0325901, Sigma), 1 000 units/ml LIF, 50 μg/ml vitamin C, and 1 μg/ml insulin (Sigma)).

Immunofluorescent staining

Cells were fixed in 4% PFA at room temperature for 30 min and washed with PBS twice. Cells were then treated with 10% FBS, 5% BSA and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min, allowing blocking and permeabilization. Incubation with various primary antibodies was overnight, 4 °C. Following primary antibody incubation and washes in 1X PBS, the cells were incubated with the Alexa-Fluor 488 or 594 secondary antibodies (1:400, Molecular Probes) and nuclei were stained with Dapi (1:5000, Calbiochem). Cells were visualized with a 10×/0.30 or 20×/0.40 (dry lens) objective using inverted microscopes (DMI4000 or THUNDER Imager 3D, Leica Microsystems). The images were captured with a digital camera (DFC365 FX, Leica Microsystems) using LAS-AF software (Leica Microsystems).

Antibodies used in this study are as following: cTNT (MA5-12960, Thermo Fisher Scientific), GATA4 (SC-25310 Santa Cruz), α-MHC (MF20) (14-6503-82, eBioscience), DDR2 (sc-81707, Santa Cruz), CD31 (e-ab-30820, Elabscience), MLC2v (ab79935, Abcam), α-Actinin (A7811, Merck).

RNA isolation and quantitative PCR

RNA isolation and quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed as described before52. qPCR was carried out with the QuantStudio 7 Flex (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using Fast SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The housekeeping Actin mRNA was used as an internal standard for normalization. Gene-specific primers used for amplification are listed in Supplemental Table S253. qPCR data are presented as fold changes relative to the indicated reference sample using 2DeltaCt comparative analysis54.

Preparation of cell extracts, SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis

Fractionated extracts were obtained as described before55. Briefly, cells were trypsinised, counted, washed with 5 ml of PBS, pelleted, resuspended in 10x of packed cell volume (usually 500 µl) of ice-cold buffer A (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.34 M sucrose, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitors), and incubated 10 min on ice. An aliquot (50 µl) of the total fraction was taken (Fraction T). After incubation, samples were centrifuged at 1,300 x g for 5 min at 4 °C. The pellet was washed with 5x volumes buffer A and then resuspended in 1x volume buffer A. An aliquot (5 µl) for the total nuclear fraction was taken (fraction N). The sample was then diluted in 10x volume of buffer B (3 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, and protease inhibitors), briefly vortexed, and incubated for 30 min on ice. Samples were centrifuged at 1,700 x g for 5 min at 4 °C. Pellets were washed in 5x volume buffer B and then resuspended in 10x volume B-SDS 1x lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 2 mM EDTA, 2% SDS) to form the chromatin fraction (fraction Chr). All fractions (except the chromatin fraction) were then mixed with an equal amount of B-SDS 2x lysis buffer, and all were boiled for 10 min. The chromatin fraction was also sonicated for 5 min at high potency (30 s ON, 30 s OFF) until clarified.

For total extracts, cells were lysed with lysis buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7,4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8, 1% Triton X-100 supplemented with cocktail protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, USA). Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, USA).

Western blot was performed as described before56, using primary antibody for Bmi1 (rabbit monoclonal, D42B3, Cell Signaling), p-Stat3 (Y705) (rabbit monoclonal, D3A7, Cell Signaling), Stat3 (mouse monoclonal, 124H6, Cell Signaling), Akt (rabbit, 9272 S, Cell Signaling), H3 (rabbit, 06-755, Millipore), pErk1/2 (p-p44/42 Mapk T202/Y204) (rabbit monoclonal, D13.14.4E, Cell Signaling), Erk1/2 (rabbit polyclonal, sc-94, Santa Cruz), Actin (Sigma) overnight at 4 °C. Blots were washed with TBST for three times and further incubated for 1 h with secondary antibodies HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Santa Cruz, USA sc-2004) and anti-mouse IgG (Santa Cruz, USA, sc-2005). Bound antibodies were detected by the ECL system (Santa Cruz, USA, sc-2048). Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ 1.52 v software.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation-qPCR analysis

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as described before57, optimized for fibroblast cells.

Briefly, cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature; the reaction was then quenched by adding glycine at a final concentration of 125 mM. The chromatin was sonicated to an average DNA fragment length of 500 to 1000 bp. Soluble chromatin extracts were immunoprecipitated using 3 to 5 µg of Ubiquityl-Histone H2A (Lys119) (D27C4) XP® (BK8240S, Cell Signaling). Appropriate IgGs (Abcam) were used as a negative control. Supernatant obtained without antibody was used as an input control. After qPCR, the results were analysed using an average of Ct of no antibody and IgG as background. The 2ΔCt of each sample was related to the 2ΔCt of the input sample. The percentage of total chromatin was calculated as 2ΔCt × 10, where ΔCt = Ct (input)–Ct (IP). Oligonucleotide pairs used have been previously described18 and are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis

Quantitative analysis of iCM was performed by flow cytometry. Briefly, reprogrammed cells were dissociated with incubation in 0.05% Trypsin/EDTA at 37 °C for 10 min, washed in PBS, and resuspended in a blocking and permeabilizing solution containing 2% FBS, 5% BSA and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min. Incubation with primary antibody α-MHC (MF20) (14-6503-82, eBioscience) was performed overnight at 4 °C. Following three washes in 1X PBS, cells were incubated with the Alexa-Fluor 488 secondary antibodies (1:400, Molecular Probes) for 30 minutes in the dark, and then analysed with a Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) flow cytometer Accuri C6 (Becton Dickinson; San Diego, CA, USA).

RNA-sequencing

The RNA-seq library preparation and libraries sequencing were performed by the Next Generation Sequencing Core Facility (LaBSSAH) of CIBIO – University of Trento. The sequencing data were uploaded to the Galaxy web platform, and we used the public server at usegalaxy.org to analyse the data58. Sequences alignment to reference genome was performed by using the RNA STAR tool. Differential gene expression analysis was done using the R package DESeq 2. The abundance of genes was used to calculate fold change and p values. Cut off values of fold change greater than 2 and p Adjusted values less than 0.05 were then used to select for differentially expressed genes between sample group comparisons.

Significant pathway enrichment analysis, Biological processes and Protein classes was performed using PANTHER Overrepresentation Test59.

Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) was used to investigate the predicted gene–gene interaction network60.

Statistical analysis

The number of biological replicates of each experiment is indicated in the figure legends. The means of at least 3 independent experiments were used to calculate SEM or SD and to perform statistical analysis (when appropriate). All P values were calculated by Student’s t test.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by PRIN-MIUR 2015 Project 20157JF8P5_002, POR Campania FESR 2014/2020 Project “SATIN” and Project “Nuove strategie per la diagnostica medica e molecolare e per la tracciabilità ed il monitoraggio dei prodotti alimentari”.

Author contributions

G.T. Conception and design, Data analysis and interpretation, Financial support, Manuscript writing, Final approval of manuscript; M.R. Collection and assembly of data, Final approval of manuscript; G.D.B. Collection and assembly of data, Final approval of manuscript; M.B. Collection and assembly of data, Final approval of manuscript; S.P. Collection and assembly of data, Final approval of manuscript; F.P. Collection and assembly of data, Final approval of manuscript; C.G.T. Data analysis and interpretation, Final approval of manuscript; P.A. Data analysis and interpretation, Final approval of manuscript; D.B. Data analysis and interpretation, Final approval of manuscript; T.R. Financial support, Data analysis and interpretation, Final approval of manuscript; F.P. Conception and design, Collection and assembly of data, Financial support, Data analysis and interpretation, Manuscript writing, Final approval of manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-63992-8.

References

- 1.Porrello ER, et al. Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2011;331:1078–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1200708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laflamme MA, Murry CE. Heart regeneration. Nature. 2011;473:326–35. doi: 10.1038/nature10147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isomi M, Sadahiro T, Ieda M. Progress and Challenge of Cardiac Regeneration to Treat Heart Failure. J Cardiol. 2019;73:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebrahimi B. In vivo reprogramming for heart regeneration: A glance at efficiency, environmental impacts, challenges and future directions. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017;108:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ieda M, et al. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by defined factors. Cell. 2010;142:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song K, et al. Heart repair by reprogramming non-myocytes with cardiac transcription factors. Nature. 2012;485:599–604. doi: 10.1038/nature11139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qian L, et al. In vivo reprogramming of murine cardiac fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2012;485:593–598. doi: 10.1038/nature11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jayawardena TM, et al. MicroRNA-mediated in vitro and in vivo direct reprogramming of cardiac fibroblasts to cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2012;110:1465–1473. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.269035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jayawardena TM, et al. MicroRNA induced cardiac reprogramming in vivo: evidence for mature cardiac myocytes and improved cardiac function. Circ Res. 2015;116:418–424. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohamed TM, et al. Chemical Enhancement of In Vitro and In Vivo Direct Cardiac Reprogramming. Circulation. 2017;135:978–995. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu Y, et al. Direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes with chemical cocktails. Cell Res. 2015;25:1013–1024. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang C, Tu W, Fu Y, Wang J, Xie X. Chemical-induced cardiac reprogramming in vivo. Cell Res. 2018;28:686–689. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0036-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao N, et al. Conversion of human fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by small molecules. Science. 2016;352:1216–1220. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Z, et al. Re-patterning of H3K27me3, H3K4me3 and DNA methylation during fibroblast conversion into induced cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Res. 2016;16:507–518. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2016.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dal-Pra S, Hodgkinson CP, Mirotsou M, Kirste I, Dzau VJ. Demethylation of H3K27 Is Essential for the Induction of Direct Cardiac Reprogramming by miR Combo. Circ Res. 2017;120:1403–1413. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirai H, Kikyo N. Inhibitors of suppressive histone modification promote direct reprogramming of fibroblasts to cardiomyocyte-like cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;102:188–190. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ifkovits JL, Addis RC, Epstein JA, Gearhart JD. Inhibition of TGFβ signaling increases direct conversion of fibroblasts to induced cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89678. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou Y, et al. Bmi1 Is a Key Epigenetic Barrier to Direct Cardiac Reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:382–395. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreso A, et al. Self-renewal as a therapeutic target in human colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 2014;20:29–36. doi: 10.1038/nm.3418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christoffels VM, Keijser AG, Houweling AC, Clout DE, Moorman AF. Patterning the embryonic heart: identification of five mouse Iroquois homeobox genes in the developing heart. Dev Biol. 2000;224:263–274. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parisi S, et al. Klf5 is involved in self-renewal of mouse embryonic stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2629–34. doi: 10.1242/jcs.027599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parisi S, et al. Direct targets of Klf5 transcription factor contribute to the maintenance of mouse embryonic stem cell undifferentiated state. BMC Biol. 2010;8:128. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujiu K, et al. A heart-brain-kidney network controls adaptation to cardiac stress through tissue macrophage activation. Nat Med. 2017;23:611–622. doi: 10.1038/nm.4326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pacheco-Leyva I, et al. CITED2 Cooperates with ISL1 and Promotes Cardiac Differentiation of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells. Stem cell reports. 2016;7:1037–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu H, Liu P, Shi X, Yin D, Zhao J. NR4A2 protects cardiomyocytes against myocardial infarction injury by promoting autophagy. Cell Death Discov. 2018;4:27. doi: 10.1038/s41420-017-0011-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sadahiro T, et al. Tbx6 Induces Nascent Mesoderm from Pluripotent Stem Cells and Temporally Controls Cardiac versus Somite Lineage Diversification. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23:382–395. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang QJ, et al. The histone trimethyllysine demethylase JMJD2A promotes cardiac hypertrophy in response to hypertrophic stimuli in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2447–2456. doi: 10.1172/JCI46277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalfon R, et al. c-Jun dimerization protein 2 (JDP2) deficiency promotes cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction in response to pressure overload. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017;249:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.08.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yokoyama S, et al. A systems approach reveals that the myogenesis genome network is regulated by the transcriptional repressor RP58. Dev Cell. 2009;17:836–848. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mashtalir N, et al. Modular Organization and Assembly of SWI/SNF Family Chromatin Remodeling Complexes. Cell. 2018;175:1272–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koga M, et al. Foxd1 is a mediator and indicator of the cell reprogramming process. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3197. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karamboulas C, et al. Disruption of MEF2 activity in cardiomyoblasts inhibits cardiomyogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4315–21. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohtaka M, Itoh M, Tohda S. BMI1 Inhibitors Down-regulate NOTCH Signaling and Suppress Proliferation of Acute Leukemia Cells. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:6047–6053. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muraoka N, et al. Role of cyclooxygenase-2-mediated prostaglandin E2-prostaglandin E receptor 4 signaling in cardiac reprogramming. Nat Commun. 2019;10:674. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08626-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou H, et al. ZNF281 enhances cardiac reprogramming by modulating cardiac and inflammatory gene expression. Genes Dev. 2017;31:1770–1783. doi: 10.1101/gad.305482.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Broughton KM, et al. Mechanisms of cardiac repair and regeneration. Circ Res. 2018;122:1151–1163. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.312586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li J, et al. Regulatory T-cells regulate neonatal heart regeneration by potentiating cardiomyocyte proliferation in a paracrine manner. Theranostics. 2019;9:4324–4341. doi: 10.7150/thno.32734,. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boulay JL, O’Shea JJ, Paul WE. Molecular phylogeny within type I cytokines and their cognate receptors. Immunity. 2003;19:159–163. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Shea JJ, Murray PJ. Cytokine signaling modules in inflammatory responses. Immunity. 2008;28:477–487. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turner MD, Nedjai B, Hurst T, Pennington DJ. Cytokines and chemokines: At the crossroads of cell signalling and inflammatory disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2014;1843:2563–2582. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thelen M. Dancing to the tune of chemokines. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:129–134. doi: 10.1038/84224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie X, Fu Y, Liu J. Chemical reprogramming and transdifferentiation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2017;46:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Onder TT, et al. Chromatin-modifying enzymes as modulators of reprogramming. Nature. 2012;483:598–602. doi: 10.1038/nature10953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhattacharya R, Mustafi SB, Street M, Dey A, Dwivedi SK. Bmi-1: At the crossroads of physiological and pathological biology. Genes Dis. 2015;2:225–239. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park IK, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Bmi1, stem cells, and senescence regulation. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:175–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI20800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang J, Liu S, Heallen T, Martin JF. The Hippo pathway in the heart: pivotal roles in development, disease, and regeneration. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15:672–684. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abad M, et al. Notch Inhibition Enhances Cardiac Reprogramming by Increasing MEF2C Transcriptional Activity. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;8:548–560. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao Y, et al. High-efficiency reprogramming of fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes requires suppression of pro-fibrotic signalling. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8243. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Passaro F, Testa G. Implications of Cellular Aging in Cardiac Reprogramming. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2018;27:43. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2018.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Efe JA, et al. Conversion of mouse fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes using a direct reprogramming strategy. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:215–22. doi: 10.1038/ncb2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo Y, et al. Chemical suppression of specific C-C chemokine signaling pathways enhances cardiac reprogramming. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:9134–9146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.006000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parisi S, et al. Lin28 is induced in primed embryonic stem cells and regulates let-7-independent events. FASEB J. 2017;31:1046–1058. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600848R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeisel A, Yitzhaky A, Bossel Ben-Moshe N, Domany E. An accessible database for mouse and human whole transcriptome qPCR primers. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1355–6. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Napolitano M, et al. Comparative analysis of gene expression data reveals novel targets of senescence-associated microRNAs. PloS One. 2014;9:e98669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beringer M, et al. EPOP Functionally Links Elongin and Polycomb in Pluripotent Stem Cells. Molecular cell. 2016;64:645–658. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fiume G, et al. Impairment of T cell development and acute inflammatory response in HIV-1 Tat transgenic mice. Sci Rep. 2015;7(5):13864. doi: 10.1038/srep13864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Navarra A, et al. Hmga2 is necessary for Otx2-dependent exit of embryonic stem cells from the pluripotent ground state. BMC Biol. 2016;31:14–24. doi: 10.1186/s12915-016-0246-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Afgan E, et al. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W537–W544. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mi H, et al. Protocol Update for large-scale genome and gene function analysis with the PANTHER classification system (v.14.0) Nat Protoc. 2019;14:703–721. doi: 10.1038/s41596-019-0128-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Szklarczyk D, et al. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D607–613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.