Abstract

Will a major shock awaken the US citizens to the threat of catastrophic pandemic risk? Using a natural experiment administered both before and after the 2014 West African Ebola Outbreak, our evidence suggests “no.” Our results show that prior to the Ebola scare, the US citizens were relatively complacent and placed a low relative priority on public spending to prepare for a pandemic disease outbreak relative to an environmental disaster risk (e.g., Fukushima) or a terrorist attack (e.g., 9/11). After the Ebola scare, the average citizen did not over-react to the risk. This flat reaction was unexpected given the well-known availability heuristic—people tend to over-weigh judgments of events more heavily toward more recent information. In contrast, the average citizen continued to value pandemic risk less relative to terrorism or environmental risk.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10393-020-01479-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Risk, Pandemic, Ebola, Survey, Risk–risk tradeoffs

Will a major shock awaken the US citizens to the threat of catastrophic pandemic risk? The current challenges to reduce the health risks from the pandemic COVID-19 suggests the answer is “no.” Many US citizens and policymakers at the national and local levels chose to downplay or ignore the COVID-19 pandemic for weeks before the stock market crash and the number of deaths began to increase at an increasing rate (Monbiot 2020; Russonello 2020). Why? To better understand this behavior, we step back and explore pandemic risk trade-offs using the case of pre- and post-Ebola in the mid-2010s. Using a natural experiment, we surveyed the US citizens about their risk–risk trade-offs before and immediately after the highly visible 2014 Ebola scare (Viscusi et al. 1991; Viscusi 2009). Using a unique survey administered both before and after the 2014 West African Ebola Outbreak, we ask the US citizens to value fatalities from pandemic risks compared to deaths from environmental disaster risks (e.g., Bhopal, Exxon, Deepwater, Fukushima) and or a terrorist attack (e.g., 9/11).

Working with Wyoming Survey and Analysis Center (WYSAC), we administered a computer-based questionnaire. After a year of pretests, in July 2013, WYSAC implemented the survey instrument in a national study distributed across the USA. The sample was a nationally representative web-based panel recruited by the online market research company, uSamp, based out of Los Angeles, California. Participants took surveys by computer. WYSAC secured 321 surveys (pre-Ebola Outbreak); 18 months later (post-Ebola), the survey was re-administered, securing 357 surveys.

Our results show that prior to the Ebola scare, people were relatively complacent and placed a low relative priority on public spending to prepare for a pandemic disease outbreak. Surprisingly, we also find that the Ebola scare did not increase the demand for preparedness among the surveyed US citizens. This flat behavioral reaction to risk was unexpected given long-standing evidence on the pervasiveness of the availability heuristic (Tversky and Kahneman 1981). Recall the availability heuristic says a person weighs his or her judgments of events more heavily toward more recent information, implying preferences toward risk should be distorted toward the most recent news item. In contrast, the average citizen continued to value pandemic risk less relative to terrorism or environmental risk.

We imagine a mix of people exists either who ignore the information altogether or people who process the information to believe the US was well-prepared relative to other risks. Diverse types of information may affect the influence of the availability heuristic. Based on the retrospective policy discussion of the Ebola scare, however, we believe it less likely that the average person presumed the US was well-prepared for a pandemic. The increased media coverage of Ebola at the time highlighted the “oversights in personal protective equipment use, disinfection, the collection, transport, and disposal of hazardous waste, the provision of social services for those placed under quarantine, and post-event monitoring and travel restrictions for potentially exposed health workers” (Kirchhoff 2016). The reporting revealed significant weakness in preparedness and implementation in its pandemic response.

Evaluating Pandemic Risk Before the West African Ebola Outbreak

We designed a stated preference survey to estimate two key measures of pandemic risk reduction based on how people trade-off lives saved from a pandemic policy relative to an environmental disaster (e.g., Bhopal, Exxon, Deepwater, Fukushima) or a terrorist attack. Viscusi et al. (1991) developed a method to measure the value of morbidity risk reductions which has two advantages to address catastrophic events. First, catastrophic risks tend to involve small absolute probabilities, which respondents find difficult to process. This method lets them focus on more readily processed comparisons such as whether preventing 100 deaths from a terrorist attack is valued more highly than preventing 100 traffic deaths. Second, “the comparisons involve a single dimension of choice—fatalities—so that respondents can focus on how fatalities are viewed without dealing with the less readily commensurable trade-off between money and fatality risks. Eliminating money as an attribute of choice also eliminates the task of establishing a credible payment mechanism for the policy” (Viscusi 2009).

Table 1 summarizes our main results for both pre- and post-Ebola outbreak surveys. In 2013, we surveyed a nationally representative US web-based panel, and found respondents valued the prevention of terrorist attack deaths and environmental disasters significantly more than pandemic outbreak deaths. Like spread betting in gambling, the person gets “points” when trading off terrorism risk for pandemic risk. If she is going to give up 1 terrorism life saved, she has to get nearly 1.5 pandemic lives saved in return. Similarly, for an environmental disaster—for giving up 1 environmental life saved, she needs 2 pandemic lives in return.

Table 1.

Valuing Catastrophic Risks: Estimation Results Using the Pre- and Post-Ebola Outbreak Survey.

| Variable | Pandemic | Environmental disaster | Terrorist attack | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-E | Post-E | Pre-E | Post-E | Pre-E | Post-E | |

| Catastrophic risk trade-off ratio: number of pandemic lives that must be saved to be equivalent to one [environmental disaster/terrorist attack] life saved | – | – | 1.82 | 1.72 | 1.51 | 1.33 |

| Demographics effects: value of lives saved (pandemic vs. environmental disaster) | ||||||

| Retired | + | + | ||||

| Asian | + | N/S | ||||

| Disabled | N/S | + | ||||

| Region 1 | N/S | N/S | ||||

| Region 3 | + | + | ||||

| Demographics effects: value of lives saved (pandemic vs. terrorist attack) | ||||||

| Retired | + | + | ||||

| Male | N/S | + | ||||

| Republican | N/S | + | ||||

| Income > $150 K | + | N/S | ||||

| Region 1 | + | – | ||||

| Region 2 | + | N/S | ||||

| Implied value of statistical life (VSL) | $4,006,372 | $4,443,081 | – | – | – | – |

Estimation results are based on the conditional logit model with fixed effects and clustered standard errors. Region 1—Mexico border, Region 2—Canada border, Region 3—Pacific Ocean border.

N/S nonsignificant.

How people valued pandemic risks varied across the population, often in expected ways. We investigated the geographic, socioeconomic, and demographic factors affecting the perceived risk of each catastrophic event as shown in Table 1. Our results illustrated that on average, retired respondents, who might perceive themselves as being more vulnerable to pandemic risks, favor policies that reduce pandemic risk over policies that reduce environmental disaster risk or terrorism risk. Respondents in states on the Mexico border and those of Asian descent favored policies that reduce the risk of environmental disasters rather than pandemics. Respondents located on the west coast and are physically removed from the 9/11 attack and the Boston Marathon bombing favored policies that reduce pandemic risk over policies that reduce terrorism risk, while respondents with income greater than $150,000 and living on the East Coast preferred policies that reduce terrorist attack risk over pandemic risk. Proximity to a catastrophic event affects value of policies to prevent that event from occurring. Further, groups who may feel more vulnerable to a particular catastrophic event will value lives saved in that scenario greater. Both patterns of results lead us to believe that respondents will place higher value on lives saved the less abstract and more realistic the catastrophic event.

This complacency was unexpected but understandable given the relatively prescient nature of the terrorism and environmental risks in relation to risk of pandemic outbreak in 2013. These differences reflect differences in risk beliefs rather than the manner in which a life is saved. People do not value the expected deaths differently, rather they have different expectations of the likelihood of death from these different causes. Our estimates suggest that people find it more difficult to quantify the risks associated with events such as pandemic outbreaks for which they have less experience.

This is in contrast to the tangible risks of terrorist attacks such as 9/11 and environmental disasters such as the 2008 Kingston Fossil Plant coal fly ash slurry spill, the 2010 Deepwater British Petroleum Inc. (BP) oil spill, or the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster. People demand more lives for environmental disasters even though that while people died in the explosion in the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, no person died in the environmental disaster following the accident. In the domestic example given to respondents (Deepwater Horizon oil spill), no human lives were lost. Many examples exist of foreign environmental disasters (Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, Chernobyl disaster) in which several thousand people died that respondents could be referencing. Respondents may also be confusing environmental disasters (preventable) with natural disasters (non-preventable), such as Hurricane Katrina.

These differences in risk beliefs make risk communication and education of the public a prerequisite for establishing a constituency for responsible pandemic policies. Our estimates illustrate that respondents were undervaluing the risk of pandemic death, which in turn is contributing to our current lack of preparedness. We appreciate that the focus of the terrorism and environmental disaster risks refer to only the US events, while the pandemic risks include the USA and several other countries, which implies that people might have focused on the US-only risks given they preferred investing in the US only. While acknowledging this point could be a possibility, we think it is less likely that respondents kept their preferences flat because they were thinking of foreign lives. Our survey communicated that there were both US risks and foreign risks to the respondents. If the respondents think that terrorism poses a risk to them and Ebola only poses risks outside the country, then the US lives would be more highly valued since their personal valuations of risk would enter.

Evaluating Pandemic Risk After the West African Ebola Outbreak

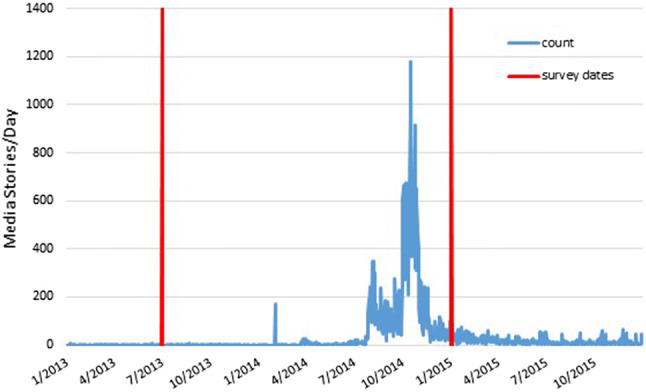

After our initial survey, the world witnessed the largest epidemic of Ebola in history, which had a 71% case fatality rate in the affected West African countries. Global media coverage was extensive and focused on how ill prepared the USA and other countries were for an Ebola outbreak (Childress 2015; Ross et al. 2014; Harhi 2014). Figure 1 illustrates the timeline of the increase in media coverage on Ebola between January 2013 and December 2015, and pinpoints when we implement both the pre- and post-Ebola survey (https://mediacloud.org/).

Figure 1.

Timeline of media coverage of Ebola [1-2013 to 12-2015] and timing of surveys.

In early 2015, we re-administered our survey to a new representative US web-based panel adding the definition of Ebola and the phrase “such as Ebola” or “like Ebola” three times throughout the survey. Based on Bayesian learning models in which people update probabilities based on information they acquire, and the availability heuristic (Tversky and Kahneman 1981), we would expect higher valuations for avoiding pandemic risks. Table 1, however, shows that the relative valuations barely changed from the first survey in 2013.

The geographic, socioeconomic, and demographic factors affecting the perceived risk also stayed consistent, with a few exceptions. Disabled respondents now (following the outbreak) value policies that reduce the risk of environmental disasters rather than pandemics, and Asian respondents became indifferent between policies (SI materials and methods). Those living on the west coast now favor policies that reduce the risk of terrorism rather than pandemics. Respondents with income greater than $150,000 and living on the east coast were now indifferent between policies, but those respondents affiliated with the Republican Party and male respondents now prefer policies that reduce terrorist attack risk over pandemic risk. Again, these results illustrate that respondents place higher value on lives saved the less abstract and more realistic the catastrophic event. Republicans placing higher value on policies that reduce terrorism is consistent with the prominence of combating terrorism in that political party’s agenda.

Using estimates from Viscusi et al. (1991), the value of statistical life (VSL) of $9.4 million (U.S. Department of Transportation 2008), as reported by the US Department of Transportation for transportation related deaths, and applying the ratios computed in Table 1, we find an average VSL of approximately $4.0 million for a life saved in a pandemic outbreak prior to the 2014 West Ebola Outbreak (see SI for more details on the calculation). When applying the VSL method, our respondents valued a life saved in a more certain traffic accident more than twice as much as a life saved in an uncertain pandemic outbreak. After the 2014 outbreak, we find the average VSL increases to about $4.4 million for a life saved in a pandemic outbreak—only a 10% increase in VSL even after the Ebola scare.

Our results illustrate that people do not always use the most available information when evaluating relative risk. They still tend to undervalue risks believed to be remote and abstract, even after a scare like Ebola. Once Ebola reached the US and the media conveyed the possible outcomes of a global outbreak, a disease with no known cure and terrifying consequences for those infected, the reality of a pandemic outbreak did not significantly affect their views.

Our findings should matter to the US policymakers who must allocate scarce resources to reduce catastrophic risk. As noted in a CNN editorial by the former US Secretary of State John Kerry, “Infectious diseases—whether naturally occurring, deliberate or accidental—have the potential to cause enormous damage in terms of lives lost, economic impact, and ability to recover, just as with nuclear, chemical, or cybersecurity attacks” (Kerry 2014). This point is emphasized by the final report released by the National Academy of Medicine’s Global Health Risk Framework for the Future (GHRF) commission. According to a Washington Post-editorial, the GHRF Commission warned: “the global community has massively underestimated the risks that pandemics present to human life and livelihoods here are very few risks facing humankind that threaten loss of life on the scale of pandemics (Mundaca-Shah 2016).”

The behavior examined here has implications beyond Ebola. HIV/AIDS, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the H5N1 strain of avian influenza, the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus, and the novel coronavirus, COVID-19, are all reminders of our vulnerability to a pandemic that would cause serious public health, economic, and development implications. The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed that the US was as unprepared as experts feared, given the responses to the Ebola scare in 2014 (The Washington Post Editorial 2016). The average US citizen in our survey was more likely to pay more to reduce terrorism risks and environmental risks than pandemic risks both before and after the substantial media coverage for Ebola. This lack of attention to pandemic threats is especially disturbing given that the current COVID-19 and any potential future pandemics that may also have very high transmission rates, including transmission before individuals become symptomatic. The present COVID-19 pandemic drives home the importance of these behavioral results and the necessity of taking stronger preventive measures than the public might consider necessary. It is critical that despite revealed compliance in the US public, policymakers continue strong investment in infectious disease preparedness.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible by the support of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Emerging Pandemic Threats PREDICT and by grant number 1R01-GM100471-01 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) at the National Institutes of Health. Contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, NIGMS, NIH, or the United States Government. Thanks to the reviewer for the useful comments and suggestions.

References

- Childress S (2015) After Ebola: Are we ready for the next epidemic? Frontline. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/health-science-technology/outbreak/after-ebola-are-we-ready-for-the-next-epidemic/

- Harhi P (2014) Media goes overtime on Ebola coverage, but not necessarily overboard. The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/media-goes-overtime-on-ebola-coverage-but-not-necessarily-overboard/2014/10/06/d65e92fc-4d8a-11e4-8c24-487e92bc997b_story.html

- Kerry, et al. (2014) Why global health security is a national priority. CNN. http://www.cnn.com/2014/02/12/opinion/kerry-sebelius-health-security/

- Kirchhoff CM (2016) Memorandum for Ambassador Susan E. Rice, subject: NSC lessons learned study on Ebola. National Security Council, White House, July 11. https://tinyurl.com/wzf6mv2

- Monbiot G (2020) Covid-19 is nature’s wake-up call to complacent civilization. The Guardian. 25 March. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/25/covid-19-is-natures-wake-up-call-to-complacent-civilisation

- Mundaca-Shah, et al. (2016) The neglected dimension of global security: a framework to counter infectious disease crises. www.nam.edu/GHRF [PubMed]

- Ross A, Olveda RM, Yuesheng L. Are we ready for a global pandemic of Ebola virus? International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2014;28:217–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russonello G (2020) Afraid of coronavirus? That might say something about your politics. NYTimes. 13 March. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/13/us/politics/coronavirus-trump-polling.html

- The Washington Post Editorial (2016) More pandemics are inevitable, and the U.S. is grossly underprepared. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/more-pandemics-are-inevitable-and-we-have-to-prepare-for-them/2016/01/21/0a77d3f8-bb0f-11e5-829c-26ffb874a18d_story.html

- This timeline media data comes from the MIT/Harvard Media Cloud news search source. https://mediacloud.org/

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science. 1981;211(4481):453–458. doi: 10.1126/science.7455683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Transportation (2008) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Transportation Policy. Memorandum: treatment of the economic value of statistical life in departmental analyses

- Viscusi WK. Valuing risks of death from terrorism and natural disasters. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 2009;38:191–213. doi: 10.1007/s11166-009-9068-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viscusi WK, Magat W, Huber J. Pricing environmental health risks: survey assessments of risk-risk and risk-dollar trade-offs for chronic bronchitis. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management. 1991;21:32–51. doi: 10.1016/0095-0696(91)90003-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.