Abstract

Purpose of Review:

Prenatal stem cell and gene therapy approaches are amongst the few therapies that can promise the birth of a healthy infant with specific known genetic diseases. This review describes fetal immune cell signaling and its potential influence on donor cell engraftment, and summarizes mechanisms of central T cell tolerance to peripherally-acquired antigen in the context of prenatal therapies for Hemophilia A.

Recent Findings:

During early gestation, different subsets of antigen presenting cells take up peripherally-acquired, non-inherited antigens and induce the deletion of antigen-reactive T-cell precursors in the thymus, demonstrating the potential for using prenatal cell and gene therapies to induce central tolerance to FVIII in the context of prenatal diagnosis/therapy of Hemophilia A.

Summary:

Prenatal cell and gene therapies are promising approaches to treat several genetic disorders including Hemophilia A and B. Understanding the mechanisms of how FVIII-specific tolerance is achieved during ontogeny could help develop novel therapies for HA and better approaches to overcome FVIII inhibitors.

Keywords: Hemophilia A, Factor VIII, Prenatal Transplantation, In Utero Gene Therapy, Fetal Immune Cells, Fetal Antigen Presenting Cells, Immune Tolerance

Introduction

Factor VIII Function and Genetic Pathogenesis of Hemophilia A.

Hemophilia A (HA) is a monogenic, X-linked disorder caused by a deficiency in coagulation factor VIII (FVIII), a vital procofactor in hemostasis. Mature FVIII is a heterodimeric (Heavy chain: A1-a1-A2-a2-B, Light chain: a3-A3-C1-C2) glycoprotein comprised of 2332 amino acids (1, 2). Normal levels of FVIII coagulant activity (FVIII:C) in plasma range from 50–150 IU/dL, but since FVIII circulates in the bloodstream bound to von Willebrand Factor (vWF), FVIII’s concentration is influenced by vWF levels, and factors affecting them, such as ABO(H) blood group and hemodynamic shear forces (3–6). Patients with severe HA have FVIII:C levels of less than 1 IU/dL, and as a result experience spontaneous bleeding ranging from subcutaneous hematomas to life-threatening intracranial hemorrhaging (7, 8). Patients with moderate HA (1–5% FVIII:C) experience most bleeding following injuries, but also have spontaneous bleeding events into their joints and muscles, while mild HA patients with more than 5% FVIII:C only sustain bleeding events after serious trauma or surgery.

Mutations associated with severe HA are diverse and can cause a spectrum of dysfunctional FVIII proteins or its complete absence, and they include inversions in intron 22 (~45%), frameshift deletions/insertions (~16%), missense mutations (~15%), premature termination mutations (~10%), single/multi-exonic deletions (~3%), splice site mutations (3%), inversions in intron 1 (2%), and other, as-yet, undefined mutations (9–11). By contrast, mutations in non-severe HA are usually missense mutations (12). Because FVIII inhibitors represent antibody-mediated responses to the missing protein, the risk of their development is related to and can be predicted from the type of mutation (13). In addition to the type of F8 mutation (9), IL-10 and TNFα-encoding gene polymorphisms (14–16), ABO(H) blood group (3, 17), African ancestry (specific to Int22 inversion (18)), high-dose (≥150 IU/kg/week) FVIII infusion during early treatment or surgery (19–22), and type of factor concentrate administered during early treatment (23–25) have all been associated with inhibitor formation.

Since HA is an X-linked disease, it typically affects males. Nevertheless, the disease can also manifest in females carrying mutations in one or both alleles of the F8 gene; severe HA can occur in female carriers due to X-inactivation of the normal F8 allele, or through inheritance of an aberrant F8 allele from both parents (26–29).

Current Standard of Care for HA and Novel Therapeutic Approaches.

Currently, the standard of care for severe HA in western countries consists of prophylactic FVIII replacement therapy using plasma-derived FVIII (pdFVIII) products and/or recombinant FVIII products (rFVIII), with standard or extended half-life (30–34). While FVIII therapy has allowed HA patients to have near normal life expectancies, the development of anti-FVIII neutralizing antibodies (FVIII inhibitors) in up to 30% of patients continues to be a major complication, rendering replacement therapy ineffective and increasing risk of morbidity and mortality (35, 36). Furthermore, the sustainability of the current Standard of Care model is far from ideal, as the HA treatment costs are estimated at an average of $300,000 per year/patient (median), while for patients with inhibitors the cost triples (37, 38).

Even though administration of very high doses of FVIII can be used in certain individuals, HA patients who develop antibodies are extremely difficult to manage. Therefore, products such as RNA interference therapeutics (39), FVIIa variants (40), and FVIII-bypassing agents have been developed that are able to circumvent the need for the deficient factor and thereby restore hemostasis.

Among FVIII-bypassing agents, a bi-specific antibody to FIX/FIXa and FX/FXa has become available for use in HA patients without inhibitors (41). Advantages of this bi-specific antibody include the estimated half-life of 2 to 4 weeks, subcutaneous administration, and the minimal risk of inhibitor formation (41–43). However, a recent study demonstrates that FIX/FIXa/FX/FXa bi-specific antibody lacks binding specificity between zymogen and enzyme (i.e. FIX vs FIXa), which causes the reaction-limiting molecule to be FIXa, instead of FVIIIa, and does not promote platelet surface binding (44). In addition patients that received FIX/FIXa/FX/FXa bi-specific antibody in combination with activated prothrombin complex concentration or FVIIa, are at increased risk for thrombotic complications, an atypical outcome in standard HA therapy (45).

In the recent years, gene therapy (GT) has emerged as a promising approach for severe HA. In the US, there are currently 6 ongoing GT clinical trials for the management of HA, all of which are using AAV-based vectors to deliver the F8 transgene (46). In the first of these, a Phase I/II dose escalation study (BioMarin; BMN 270) [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02576795] involving 9 severe HA patients, results to date have shown that a single administration of an AAV serotype 5 (AAV5) vector encoding a hF8 transgene under the control of a liver-specific promoter can yield durable circulating FVIII:C levels within the normal/healthy range (>50 IU/dL) (47). Specifically, one-year follow-up has shown normal FVIII:C levels in patients who received a single high-dose (6×1013 vector genome per kg [vg/kg]) of BMN 270, while patients in the low-dose and intermediate-dose cohorts had circulating FVIII:C levels that peaked at only 3 IU/dL. While no AAV5 capsid-specific immune responses nor FVIII inhibitors were reported, elevated transaminase levels in the first high-dose patient led physicians to implement prophylactic prednisolone in the remaining patients. Despite this auspicious start, however, available three-year data suggest that the plasma FVIII levels are declining and the patients may have to be treated again in the future to maintain therapeutic levels.

In another Phase I/II study (48) (SPK-8011; Spark Therapeutics) [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03432520] a novel liver-tropic AAV vector encoding a B-domain deleted (BDD) human F8 transgene was used. The study has shown up to 14% FVIII:C in its intermediate dose cohort of 5×1012 vg/kg, thereby surpassing the conservative study goal of 12% FVIII:C that was assumed to be necessary to prevent spontaneous bleeding. However, 2 of the patients developed significant immune response to the AAV capsid, one of which required hospitalization. This anti-capsid response, and the steroid therapy administered to counter it, led to a drop in FVIII levels to below 5% in these patients (48).

Bayer also recently initiated a Phase 1/2 open-label safety and dose-finding study of their AAV therapeutic, BAY2599023 (DTX201), in 18 adults with severe HA [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03588299]. This trial began enrolling in November 2018, and no results have yet been reported. Shire has also launched a global Phase I/II dose escalation study (clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03370172) to use an AAV8 vector encoding a BDD F8 transgene (SHP654/BAX 888) in a total of 10 participants.

A cost-effectiveness analysis was performed to compare the treatment of severe HA via GT vs. by FVIII prophylaxis, and this analysis supported significantly lower per-person costs for GT over 10-year timeframes (49). Unfortunately, however, the presence of pre-existing immunity to AAV in as many as 60% of individuals (depending on donor age and AAV serotype) severely limits the number of patients who can potentially benefit from this type of therapy (50–52). Furthermore, after AAV vector exposure, patients may become immunized against the capsid and develop high titers of neutralizing antibodies (Nabs) that persist long-term, precluding patients from receiving another dose of an identical product (53). Administering the AAV vector during the prenatal or neonatal period could solve this problem, since treatment during this window of time would ensure the vast majority of patients are devoid of pre-existing immunity. However, little is currently known about the possible inflammatory responses and potential hepatoxicity that may result from vector-host interactions after in vivo administration of AAV vectors during these early developmental stages, highlighting the need for further carefully designed safety studies prior to implementing AAV-based GT in fetal/neonatal recipients (54). If, however, instead of directly injecting viral-based vectors into the recipient, suitable cells were modified in vitro and then used as vehicles to deliver the therapeutic transgene, a much greater degree of manufacturing control would be afforded, and GT could be applied to neonatal and even fetal recipients with far lower risk and improved safety. In the following sections, we provide a concise background on prenatal cell transplantation and then focus on the use of such an approach as a treatment for HA.

Prenatal Transplantation (PNTx) as a Treatment for Hemophilia A

PNTx holds great promise for treating/curing many inherited genetic diseases early in gestation, (55, 56). To-date PNTx has been performed on a compassionate-use basis in roughly 50 patients in an effort to treat 14 different genetic disorders (57–59). Specifically, regarding the use of PNTx to treat HA, HA is the most common inheritable coagulation deficiency (60) and 75% of HA patients have a family history. Thus, prenatal diagnosis is feasible, available, and strongly encouraged in most Western and developing countries (61–71). Digital PCR now allows analysis of free fetal DNA in maternal plasma, making non-invasive in utero diagnosis of HA possible as early as 7 weeks of gestation (70). Furthermore, prenatal diagnosis and family history can predict whether patients will have severe, moderate, or mild HA and their likelihood of developing inhibitors to FVIII. Of note, performing PNTx to treat HA would circumvent the immune barriers present in adult patients, and could induce immunological tolerance to therapeutic antigens, such as FVIII (72–77), and thereby eliminate the risk of inhibitor formation (78–82) if/when subsequent postnatal treatment is needed.

When considering a prenatal treatment, safety is obviously of the utmost importance. It is therefore critical to note that during early fetal life, activation of FX occurs predominantly via tissue factor activity, making it largely independent of the FIXa/FVIIIa phospholipid complex (83). As a result, the fetus develops without hemorrhage, despite having little or no expression of FVIII and FIX (83–85). The unique hemostasis of the fetus should thus allow prenatal treatment to be performed safely for HA; indeed, one of the 50 human patients that received PNTx was transplanted with fetal liver cells in an effort to correct HA, and although the patient was not cured, immune tolerance to FVIII was induced, and the patient did not developed the high-titer inhibitors from which the patient’s siblings had suffered (86). Taken together, these data provide compelling evidence that HA is a highly promising candidate disease for treatment prior to birth (reviewed in greater detail in (87, 88)).

Human Fetal Immune Development and the Unique Opportunity to Induce Tolerance

It was a long-held assumption that the fetal immune system was immature and the fetus was, for all intents and purposes, immuno-naïve since it develops in a sterile environment without exposure to foreign antigens. In recent years, however, there has been an ever-growing appreciation that the developing immune system is, in fact, in contact with many immune stimulatory molecules (89) such as maternal haploidentical antigens (90–92), microbes, materials present in the amniotic fluid, and food antigens (93). As a result, it is now acknowledged that although the immune system may only reach full maturity several years after birth, the immune system begins to develop and gains a surprising degree of functionality fairly early during gestation.

Looking at clinical studies data to date, it is interesting to note that, although the fetal immune system is known to allow the engraftment of haploidentical or allogeneic donor cells (94, 95), clinical success with PNTx using hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) has thus far been limited to recipients with immunodeficiencies, conditions in which donor cells would be predicted to possess a selective proliferative and/or survival advantage over the cells of the host (58, 96–99). Because HSC-PNTx is performed without myeloablation or immunosuppression (to avoid possible risks/toxicities to the fetus and mother), immunologic barriers and the absence of stress-induced signaling have been considered as significant contributors to the limited donor HSC engraftment (100–102) thus far seen in patients with diseases that would not be expected to confer a selective advantage to the transplanted donor cells. It is worth noting that the majority of human patients have, in fact, engrafted following HSC-PNTx, irrespective of their underlying disease, and the levels of engraftment, while not high enough to mediate disease correction, were sufficient to induce immune tolerance to the donor (100–102). Importantly, the induced state of tolerance was donor-specific, since the recipient maintained normal immune-reactivity to unrelated third-party antigens (100–102). Despite the obvious clinical importance, the specific pathways present within the fetus that make it possible to achieve a state of immune tolerance as a result of prenatal exposure to exogenous antigens are not currently well understood, although existing evidence suggests that adaptive immune cells of the fetus are likely to be the primary contributors to the pro-tolerogenic signaling that exists toward haploidentical cells present in fetal tissues during gestation.

In the following sections, we will provide an overview on the prevailing thoughts regarding some of the processes thought to play a role in maintaining the delicate yet critical balance between immunity and tolerance during fetal life and will review mechanisms by which PNTx is thought to promote the induction of immune tolerance to exogenous proteins and/or donor cells that are introduced to the fetus during gestation and place these data in the context of using PNTx to treat HA.

Induction of central tolerance during fetal development

The fetal immune system differs from that of the adult in that it lacks a robust response to foreign antigens, with fetal T cells being more likely to engage in promoting tolerance. During fetal life, T cell progenitors are educated in the thymus, a primary lymphoid organ, to ensure development of tolerance to self-antigen and non-inherited maternal antigen (NIMA) (103). Studies of human thymus organogenesis have shown that the first T-lineage affiliated CD34int CD45+CD7+ hematopoietic progenitor cells enter the developing thymus by 8 gestational weeks (gw) (104), and can become CD4/CD8 double-positive (DP) thymocytes soon after (105). Concurrently, cortical thymic epithelial cells (TEC) and medullary TEC undergo sufficient differentiation to orchestrate a diverse array of thymocyte selection processes (104). Cortical TEC are the primary mediators of positive selection, a process during which DP thymocytes with low affinity/avidity for peptide-MHC are rescued from programmed cell death, undergo CD4 or CD8 single-positive T cell commitment, and begin to express elevated levels of CD69, an early activation marker (106). After chemokine-based recruitment to the medulla, the maturing thymocytes with low affinity become classified as naïve CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, and emigrate to the fetal periphery by 14–16 gw (107), while those exhibiting high reactivity to peripherally- or thymus-acquired antigen (Ag), presented on antigen-presenting cells (APC), undergo depletion. Alternatively, in the presence of medullary thymic epithelial-produced thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), dendritic cells (DC) resident within the medulla can instruct these high-affinity thymocytes to differentiate into natural Treg cells (nTreg) (108–111), whose repertoire is capable of establishing immunotolerance. Other APC subsets, including B lymphocytes, are also known to contribute to thymic central tolerance (112, 113). However, a complete picture of this complex process will require further studies to characterize the precise roles (if any) played by such APC subsets in the induction of central tolerance to peripherally-acquired Ag during fetal development. Regardless, the collective outcome of these processes is a functional T cell repertoire educated for tolerance to self-Ag and NIMA

Experimental support for central tolerance induction to peripherally-acquired antigen

Looking specifically at using PNTx to induce immune tolerance to a circulating protein like FVIII, experimental studies performed in post-natal mice have identified the steady-state myeloid conventional DC2 (cDC2) and plasmacytoid DC (pDC) subsets of APC as being responsible for presenting peripherally-acquired antigens within the thymus (109, 114–117). The first of these studies demonstrated that cDC2 capture bloodstream Ag, endocytose the Ag in a clathrin-dependent manner, migrate to the thymus via C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2), and finally present the Ag at the cortical parenchyma (118, 119). Subsequent studies affirmed that cDC2-presented Ag can contribute to central tolerance by inducing thymocyte recruitment to the medulla and driving clonal deletion of Ag-reactive thymocytes, as well as inducing the differentiation of Ag-specific nTreg (120–123). More recent studies suggest that cDC2 (124, 125), participate in Ag-transfer via MHC-I and MHC-II uptake from medullary TECs (126).

A variety of biomarkers have been proposed to identify subsets of pDC that have tolerogenic properties. In early studies, resting CCR9+ pDC were identified to have immunosuppressive properties when they were shown to induce the differentiation of Ag-specific Treg cells to peripherally-acquired Ag (127, 128). Soon after, Martin-Gayo et al. (129) provided compelling evidence that CD13− pDC present within the human thymus are pro-tolerogenic by showing that these cells were able to induce the differentiation of positively-selected DP thymocytes to nTreg upon CD40L and IL-3 stimulation and CD80/CD86 signaling. In the same year, Hanabuchi et al. showed that, upon stimulation, purified pDC begin to express TSLP receptor, and that upon binding of TEC-produced TSLP, these pDC secrete chemokines that promote medullary recruitment of positively-selected thymocytes (123), while also inducing DP thymocytes to undergo differentiation to nTreg (130). The authors also noted that the tolerogenic pDC secreted higher levels of IL-10, compared to that secreted by conventional DC.

In addition to cDC2 tolerogenic effect within the thymus, fetal cDC2 can also induce peripheral tolerance to alloantigen by localizing to lymph nodes and mediating antigen-specific inducible Treg cell differentiation (93).

Experimental Work Optimizing PNTx in the Context of HA

The therapeutic potential of PNTx has been demonstrated in human patients with primary immunodeficiencies and osteogenesis imperfecta (57, 58, 96, 98, 131). As discussed above, HA can easily and noninvasively be diagnosed prenatally. For many medical and biological reasons, PNTx represents an ideal modality for treating HA, and the rationale for this approach to HA treatment has been reviewed previously (87, 88). For PNTx to be a safe and successful treatment approach for HA (and a variety of other genetic diseases as well), it will be critical to use donor cells that can evade HLA-directed immunogenic responses. Almost all clinical prenatal transplants performed to-date have used HSC. When considering the treatment of HA, there is no reason to limit our consideration of potential donor cells to those of hematopoietic origin. Indeed, by expanding the scope of putative donor cells to include those that possess a phenotype similar to that of the fetal trophoblast or placenta, it may be far easier to induce tolerance to donor cells, due to their lack of expression of immunogenic HLA Class II antigens, and the expression of non-classical Class Ib HLA-G or HLA-E (132). Indeed, there has been a great deal of interest in the use of amniotic fluid- and placenta-derived cells for PNTx to target multiple genetic disorders (133–135).

Since the discovery of stem cells within the amniotic fluid and the subsequent demonstration of their potential as therapeutics (134–136), investigators have been studying mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) derived from both amniotic fluid (AFSC) and the placenta (PLC) as cellular therapeutics for PNTx. Their relatively non-immunogenic profile and their ability to be extensively expanded without exhibiting genomic instability or undergoing transformation have further fueled these efforts. Looking specifically at their immune-modulating properties, AFSC and PLC have both been shown to inhibit lymphocyte activation, stably produce a tolerogenic secretome, contribute to multiple mechanisms of tissue regeneration, and have demonstrated the potential for long-term engraftment (134, 136–138). In the context of HA treatment, these unique immunological properties may make AFSC or PLC ideal donor cells to provide a non-immunogenic cellular platform for the long-term secretion of therapeutic levels of FVIII, prenatally, and perhaps even postnatally.

When considering the use of PLC as cellular therapeutics, it is important to note that PLC can be derived from both the maternal (decidual tissue) and the fetal side of the placenta. Given their earlier ontogenic state, investigators are actively focused on developing methods to optimize isolation of PLC of fetal origin. Sardesai and colleagues demonstrated that, via a specific cotyledonary core dissection and large-scale explant culture, fetal PLC can be reproducibly isolated (139). Steigman and Fauza also described a method of isolating MSC from the fetal side of the placenta (140) and showed that these cells exhibited a spindle-shaped fibroblast-like appearance characteristic of MSC isolated from adult tissues and had the ability to be extensively expanded ex vivo. MSC isolated in this manner expanded more quickly in vitro than adult MSC and were both less immunogenic and more potent immunosuppressors than their adult counterpart (141–143). More recent studies have further refined these isolation methods by demonstrating that PLC, in similarity to their counterparts in the amniotic fluid, can be further enriched for stem-like properties and broadened differentiative capacity by including a step to select for the c-kit+ subpopulation of those cells exhibiting plastic-adherence (144, 145). Despite their promise, however, additional studies are still needed to establish their long-term in vivo stability, differentiative fate, and safety following PNTx. Ideally these cells should have a broad engraftment/integration capability, enabling them to exploit the space and permissive environment created by the rapid fetal growth. In addition, these cells should have low immunogenicity, so they can elude the nascent immune system to engraft at therapeutic levels and persist long enough to induce tolerance.

Experimental Work Optimizing in Utero Gene Therapy (IUGT) in the Context of HA

Given the extremely low endogenous level of FVIII production/secretion by most cell types being considered as therapeutics (146, 147), it is unlikely that PNTx with a single infusion of cells that endogenously produce and secrete FVIII would be sufficient to achieve normal circulating FVIII levels (100–200ng/mL). Rather, to achieve clinically meaningful levels of circulating FVIII following PNTx, it will likely be necessary to either inject vectors directly into the fetal recipient (as is being done postnatally in ongoing AAV-based clinical trials) or infuse cells that have been modified to constitutively and robustly express native or expression-enhanced FVIII transgenes.

While gene delivery technology has advanced exponentially over the past decades, FVIII is a challenging protein to express ectopically, as it is large and heavily glycosylated, which places a great deal of stress on the cell’s secretory machinery (148–152). To address this issue, investigators have pursued multiple avenues in efforts to maximize the amount of exogenous vector-derived FVIII that reaches the circulation. These efforts have included modifying native gene promoters and/or synthesizing artificial promoters, performing codon-optimization of the FVIII transgene, and bioengineering FVIII to alter its protein structure, to improve transcription, translation, and secretion, respectively. In a striking example of the first of these approaches, Brown and colleagues developed a bioengineered FVIII cassette, delivered it in the context of an AAV vector, and demonstrated its potent therapeutic potential in the management of HA (153). Compared to the strongest known liver-directed promoter, the 252-bp HLP (154), the authors iteratively designed and developed a shorter 146-bp synthetic promoter comprised of a transcription-driving α-microglobulin/Bikunin precursor (abp) fragment stripped of non-transcription factor-binding regions, a Xenopus laevis albumin (SynO) fragment, and a transcription start site (TSS). The authors termed this new engineered promoter the hepatic combinatorial bundle (HCB), and they showed that it is capable of driving 14-fold higher FVIII expression (vs. HLP), as measured by FVIII chromogenic assay, after hydrodynamic injection of plasmid DNA in a murine HA model.

These same authors also described a method for codon-optimization to maximize expression within the desired target tissue and showed that, in the context of HA, a liver codon optimization can yield 7-fold higher FVIII expression in vivo compared to traditional human genome coding DNA-based codon optimization methods derived from an ancestral FVIII-encoding gene. Very intriguingly, a vector dose of 1×1011 vector genomes (vg)/kg of a liver codon-optimized AAV-FVIII vector with a porcine A2 domain-encoding region was shown to sustain FVIII:C greater than 100 IU/dL after 16 weeks in murine HA models. This is a 600-fold lower dosage in comparison to a recent clinical trial that required a single 6×1013 vg/kg dose to achieve sustained levels higher than 50 IU/dL (47), attesting to the remarkable gains that can be made in plasma FVIII levels by optimizing the transcription and translation of the FVIII transgene.

Modulation of protein structure has also been shown to improve the efficiency with which FVIII is secreted. Another AAV-based study recently showed that by deleting the furin cleavage site in a human B domain-deleted (hBDD) FVIII cassette, the resultant change in FVIII structure led to a 2- to 4-fold increase in FVIII expression in vivo (155). Collectively, such preclinical evidence strongly argues for the immense promise of vectors containing bioengineered FVIII variants in future GT approaches for HA.

More recently, another research group created an LV construct designed to target FVIII expression to liver sinusoid endothelial cells (which are thought to be the predominant natural site of FVIII synthesis in the body) through the incorporation of a vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin) promoter in HA mice (156). The study reported sustained FVIII:C levels of 5–6 IU/dL for up to 1-year post-injection in the absence of FVIII inhibitors. This remarkable feat was the result of preventing transgene expression in pDC via the incorporation of a target site for miR-126 (a miRNA found abundantly in pDC) within the LV.

As a result of the advances afforded by this multi-tiered approach to FVIII production and secretion, it is now possible to express an exogenous FVIII cassette in a variety of cells and tissues both in vitro and in vivo, and it has been some of these very advances that enabled the recent postnatal gene therapy clinical trials for the treatment of HA discussed earlier in the review. However, given the uniqueness of the ethical and scientific considerations surrounding the prenatal application of gene therapy, the International Fetal Transplantation and Immunology Society (IFeTIS) recently published a Consensus Statement outlining the key criteria for considering treatment with IUGT to help advance IUGT towards clinical realization. These criteria included: 1) reliable prenatal enzymatic or genetic diagnosis, 2) a strong genotype/phenotype correlation impacting clinical prognosis, and 3) the need to exploit the immunologic environment at the time of treatment to prevent pre- or postnatal immune reaction to the transgene-encoded protein (55, 56). HA meets all of these criteria, highlighting the potential of IUGT as a viable treatment approach for this disease.

Looking first at the approach of directly injecting viral-based vectors into the fetal recipient to mediate gene transfer/correction, a variety of animal model systems and rodent models of human genetic diseases and a wide range of transduction methods have been employed. These studies have collectively demonstrated that direct vector injection-based IUGT can be used to target multiple organs, and phenotypic rescue has been accomplished with this approach in several different disease models (72, 75, 76, 77, 157–203). Our group has spent the last two decades performing IUGT studies in the sheep model (75, 77, 161–166, 193, 197–202), and we have shown that it is possible to take advantage of the unique temporal window of relative immuno-naïveté during early gestation to efficiently deliver exogenous genes to a variety of fetal tissues and induce durable tolerance to the vector-encoded gene product (77, 202). This tolerance induction appears to involve both cellular and humoral mechanisms, since antibody and cellular responses to the transgene product were both significantly diminished in these animals, even several years after IUGT.

Looking specifically at using IUGT to correct the hemophilias, promising studies demonstrated that injection of FIX-encoding lentiviral (LV) or AVV vectors into mouse fetuses resulted in therapeutic levels of FIX and improved coagulation post-IUGT. Furthermore, no immune response developed to FIX, even when the protein was repeatedly injected postnatally (76, 177).

Collectively, the results of all of the afore-mentioned studies strongly imply that IUGT, even if it not curative, would still be an ideal treatment modality for HA, since the induced immune tolerance would ensure that postnatal therapy, be it protein- or gene-based, could proceed safely without any of the immune-related problems that currently plague HA treatment.

In a more recent example of the potential of IUGT, Peranteau and colleagues performed direct injection AAV-mediated IUGT in fetal sheep at 60 to 65 days of gestation (term = 150 days). These studies showed sustained expression of AAV vector-encoded GFP for up to 6 months postnatally, as well as the induction of immune tolerance to the vector-encoded GFP (72). Similarly, another study by Chan and colleagues achieved long-term expression and immune tolerance to human coagulation FIX for up to 6 years after a single, direct in utero injection of an AAV-FIX vector to healthy fetal nonhuman primates, thereby establishing proof-of-concept for treating hemophilia B prior to birth in this highly translational animal model (203).

Interestingly, however, in both of these studies (performed in two different species), the authors observed postnatal immunity to the capsid of the specific serotype of AAV used in the study. The absence of immune tolerance to the vector capsid is perhaps not surprising, given the very brief time that the capsid proteins/peptides would be expected to be present following injection. Given the brevity of exposure of the fetal immune system to the capsid and its proteasomal degradation products, however, the induction of immunity is unexpected, and such immunity would preclude the ability to perform a subsequent postnatal “boost” with the same vector preparation to enhance the levels of transgene expression, if needed to reach a therapeutic target range.

While new AAV serotypes and AAV hybridization approaches promise to one day enable avoidance of such AAV capsid-directed immunity (204–206), to-date the prevalence of pre-existing anti-AAV antibodies in the general population and the possibility of acquired anti-AAV capsid immunity has thwarted AAV-based clinical approaches to treat multiple genetic diseases. These immunological hurdles, combined with significant safety concerns over off-target effects (87, 161, 163) and the possible toxicity of delivering viral vectors directly in vivo (207), has fueled the search for alternative approaches for safely delivering a FVIII transgene to correct HA.

One of the most promising of these approaches is using cells as vehicles to deliver a FVIII expression cassette. In support of this approach, a number of preclinical studies have established the feasibility of using a variety of viral-based vectors encoding FVIII cassettes to achieve high levels of secreted FVIII:C activity in vitro and in vivo from a variety of clinically relevant cell types (153, 155, 208–221). Among the candidate viral vectors, those based upon lentiviruses have shown great promise, due to their ability to transduce a wide range of cell types, to permanently integrate their genetic cargo into the genome of the host, and to efficiently transduce both dividing and quiescent target cells (222–224). It is important to note that LV vectors are currently being used in multiple clinical trials [ClinicalTrials.gov and (205)], establishing both their safety and their tremendous utility/potential. Looking specifically at using LV vectors in the context of HA, experimental studies by Doering and colleagues using a self-inactivating (SIN) LV vector have shown promising results in postnatal GT for HA (209). In this study, the authors incorporated a bioengineered hybrid FVIII gene containing the porcine A2-domain to achieve enhanced secretion, and they utilized the CD68 promoter to drive myeloid-specific expression. In combination, these two modifications led to a marked enhancement in the circulating levels of FVIII:C in HA mice following transplantation with LV-transduced human CD34+ HSC.

Shi and colleagues have spent several years exploring the possibility of harnessing the natural potential of platelets as transporters of FVIII in the context of gene therapy treatments for HA. In their first study, they showed that by combining the use of an LV vector (2bF8LV) encoding a platelet-specific promoter (αIIb) driving FVIII expression, and a drug resistance gene, MGMTP140K, it was possible to transplant these transduced HSC and, after in vivo drug-selection, achieve normalized FVIII:C in the absence of anti-FVIII antibodies for up to 12 weeks post-GT in a murine HA model (225, 226). Miao and colleagues greatly simplified this complex and potentially toxic approach by showing that it is possible to administer a single intraosseous injection of a FVIII-encoding LV vector and thereby transduce HSC in vivo and achieve platelet-specific expression of FVIII that corrects the bleeding phenotype of HA mice, even in the presence of inhibitors (227). More recently, Shi and colleagues demonstrated that, using the same 2bF8LV GT, peripheral tolerance may be occurring via increased Treg cell levels upon FVIII re-stimulation (228). Notably in this study (228), however, successful peripheral tolerance was only achieved in conjunction with either irradiation or busulfan + antithymocyte globulin dosages. In further mechanistic studies, Shi and colleagues used an ovalbumin transgene to show that platelets store and transport this vector-encoded protein in α granules post-GT, and that this platelet-targeted approach to GT results in ovalbumin-specific humoral and cellular peripheral tolerance in vivo (229).

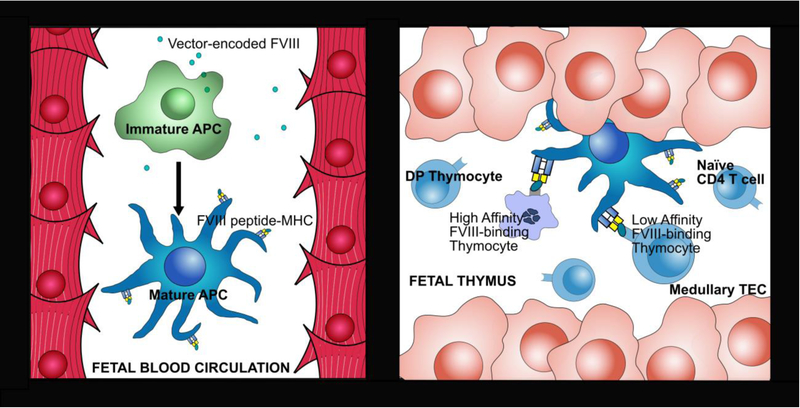

In contrast to the limited peripheral tolerance that has been achieved in the preceding postnatal studies, IUGT may offer the potential to induce “permanent” central tolerance to FVIII, without the need for nonspecific immunomodulation regimens, via deletion of reactive FVIII-specific T cell deletion or the induction of natural Treg differentiation during development of the fetal lymphocyte repertoire. Nevertheless, studies are still needed to define the minimal circulating FVIII levels that are required following IUGT for APC (potentially cDC2 and/or CD123+ pDC) to effectively uptake and present FVIII peptide at an adequate affinity and avidity to lymphocyte progenitors (thymocytes) during fetal development to induce central tolerance (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Intrathymic presentation of peripherally-acquired FVIII by APC during fetal development.

a) After PNTx/IUGT, vector-encoded FVIII produced by transplanted cells, or by vector-modified cells, is taken up by antigen-presenting cells (APC) either in peripheral circulation or within the fetal thymus by resident APC. b) The FVIII peptide is then presented by MHC molecules on fetal APC to T cell progenitors (thymocytes) in the thymic medulla. Throughout gestation, thymocytes with low/moderate affinity will exit the thymus as naïve T cells that are tolerant to the vector-encoded FVIII, while those with modest-high affinity will become FVIII-specific natural Treg cells, and those with excessively high affinity will undergo cell death, preventing postnatal anti-FVIII immunity. TEC = thymic epithelial cell.

To date, there has been only a single study looking specifically at the possibility of using gene-modified cells to treat HA via IUGT. This very recent report demonstrated the feasibility of transducing human PLC with a LV encoding a truncated FVIII transgene for use in PNTx (230). The transduced PLC secreted biologically active FVIII coagulation activity (FVIII:C) at levels of 1.11 IU/106 cells and maintained the capacity for trilineage differentiation post-transduction. The authors then performed PNTx with these transduced PMSC in healthy wild-type mice and demonstrated the presence of donor cells in several organs soon after birth. While establishing basic proof-of-principle, the authors did not assess long-term engraftment of the PMSC, the circulating levels of vector-derived FVIII, nor the potential for PNTx to induce immune tolerance to FVIII, leaving unanswered the question of the long-term therapeutic potential of this approach.

A new exciting gene transfer technology that warrants mention is that of non-viral delivery platforms, which are becoming more prevalent in preclinical studies. A striking example of the remarkable advances being made in this field is the recent innovative study by Saltzman and colleagues, who performed direct intravenous and intra-amniotic injections in utero of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-encapsulated nanoparticles (NP) containing triplex-forming peptide nucleic acids (PNA) to correct the IVS2–654 mutation that causes β-thalassemia (231). In contrast to the viral vectors used in most IUGT studies to-date, this biodegradable and biocompatible NP-based system uses high-fidelity endogenous DNA repair mechanisms, including homology-directed repair pathways, thereby minimizing the possibility of insertional mutagenesis. This approach yielded efficient delivery to the fetal liver and led to significant phenotypic improvement of β-thalassemia postnatally. Equally as important as its therapeutic efficacy, this approach did not result in any developmental abnormalities nor inflammatory cytokine responses, and the authors documented an impressive 100% survival rate at 500 days post-IUGT. The authors insightfully capitalized on the naturally-occurring high gene-editing frequency in the fetal liver and fetal BM (232) to drive site-directed donor gene integration and confirmed that higher gene-editing levels are achieved in utero when compared to postnatally, and thereby highlighting another unique therapeutic advantage of IUGT (233).

Placing this new non-viral delivery system in the context of HA, one can envision future studies using PNA-containing NP to achieve site-specific integration of expression/secretion-optimized engineered FVIII transgenes within AFSC and/or PLC which could then be used to treat HA via PNTx and bypass possible risks/concerns associated with the use of viral-based vectors in the fetal recipient. Such studies would obviously need to include optimization of the dosing and gene-editing efficiency of the PNA-containing NP in utero, validation of specificity of genomic integration of the donor gene, and assessment of the long-term stability of the gene-corrected cells in vitro and in vivo in preclinical animal models of HA. And most importantly, these studies will need to rigorously verify the safety of this approach to IUGT.

Concluding remarks

Great strides have been made in the understanding of the structure and function of FVIII, the deficiency of which leads to Hemophilia A (HA), and this improved understanding has enabled vast improvements in the standard of care for children and adults suffering from the disease. The identification and characterization of the human FVIII gene by Jane Gitschier in 1984 (1), followed by the concept of B domain deletion in 1988, which was pioneered by the John Toole laboratory, as well as the characterization of FVIII activation requirements by Debra Pittman in the same year, each helped to pave the way for the clinical reality of prophylactic FVIII replacement therapy that is available today.

Currently, prophylactic FVIII infusions safely and effectively enable sustained restoration of normal hemostasis, thereby preventing bleeding events and enabling HA patients to live near normal lifespans; both remarkable clinical achievements. Unfortunately, this standard of care is not accessible to many of the world’s HA patients nor is it financially palatable. Current treatment regimens are lifelong and noncurative, leading to a reduced quality-of-life, and are estimated to cost over $300,000 per year, with much higher costs for the >30% of severe HA patients who develop FVIII inhibitors (37, 38). Clearly, there is much room for improvement in the clinical management of HA. In contrast to current replacement therapy, the successful delivery of FVIII-encoding vectors or cells modified with such a vector could promise prenatal correction of HA and long-lasting, ideally lifelong, phenotypic correction of the disease. Equally as compelling, intervening early in gestation should enable the induction of central tolerance to the exogenous FVIII protein by piggybacking upon the naturally-occurring intrathymic, peripheral antigen presentation via fetal APC subsets throughout prenatal lymphocyte selection (Figure 1). Thus, even if prenatal treatment did not provide long-term curative circulating levels of FVIII, it should ensure the patient would never form inhibitors to FVIII, thus overcoming the major complication in the management of HA patients today.

Regarding ensuring adequate levels of engraftment of donor cells following PNTx, the documented tolerogenic propensity of fetal immune cells to maternally-derived haploidentical cells supports the potential for using maternal cells for PNTx to minimize the risks of rejection/graft failure. Looking beyond the HSC that have been used in the majority of clinical PNTx performed to-date, many experimental studies have also demonstrated meaningful levels of engraftment following PNTx using mesenchymal stromal cells derived from chorionic villous sampling, amniotic fluid, full-term placenta, or the umbilical cord, all of which possess intrinsic advantages over HSC with respect to immunogenicity, genomic stability, and the ability to be expanded extensively in vitro (133, 230).

To maximize FVIII biosynthesis following gene delivery, elegant studies have demonstrated the substantial impact that target cell-specific promoters, codon optimization, and bioengineering of the FVIII protein, as well as subtle protein structural alterations to bypass the unfolded protein response pathways, can all have on the levels of FVIII that are produced and secreted into the circulation.

Combining these advances in FVIII biology with those in PNTx, the field is uniquely poised to begin developing and optimizing prenatal treatments for HA. It is important to note that the great strides made in recent years with postnatal GT are the result of decades of extensive experimental work to define the efficacy and safety of the approaches to be applied to human patients and to move through the extensive regulatory intricacies of this new, untested molecular therapy. Based on the tremendous advances that have been made in recent years, dual initiatives have been made by the NIH and FDA to better streamline the clinical research oversight system as it pertains to GT (234), including changes to the review and reporting processes to encourage and ensure full transparency with respect to the safety and efficacy of candidate therapies.

With these new streamlined processes and the remarkable ongoing advances in both non-viral and viral gene delivery, we are optimistic that IUGT will soon become a clinically viable treatment option for patients with HA (and numerous other genetic disorders, as well). Prior to clinical implementation however, critical questions concerning IUGT’s long-term efficacy, safety (to the fetus and the mother), and its potential to induce immunological tolerance to the vector-encoded proteins must first be answered in biologically relevant and clinically-predictive animal models.

Funding Source:

The authors are supported by NIH, NHLBI, HL130856, HL135853, and HL148681

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References:

- 1.Gitschier J, Wood WI, Goralka TM, Wion KL, Chen EY, Eaton DH, Vehar GA, Capon DJ, Lawn RM. Characterization of the human factor VIII gene. Nature. 1984;312(5992):326–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen BW, Spiegel PC, Chang CH, Huh JW, Lee JS, Kim J, Kim YH, Stoddard BL. The tertiary structure and domain organization of coagulation factor VIII. Blood. 2008;111(3):1240–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-109918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Donnell J, Laffan MA. The relationship between ABO histo-blood group, factor VIII and von Willebrand factor. Transfus Med. 2001;11(4):343–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connelly S, Gardner JM, Lyons RM, McClelland A, Kaleko M. Sustained expression of therapeutic levels of human factor VIII in mice. Blood. 1996;87(11):4671–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galbusera M, Zoja C, Donadelli R, Paris S, Morigi M, Benigni A, Figliuzzi M, Remuzzi G, Remuzzi A. Fluid shear stress modulates von Willebrand factor release from human vascular endothelium. Blood. 1997;90(4):1558–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kepa S, Horvath B, Reitter-Pfoertner S, Schemper M, Quehenberger P, Grundbichler M, Heistinger M, Neumeister P, Mannhalter C, Pabinger I. Parameters influencing FVIII pharmacokinetics in patients with severe and moderate haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2015;21(3):343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konkle BA, Huston H, Nakaya Fletcher S. Hemophilia A. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Stephens K, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews((R)). Seattle (WA)1993. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kay MA, High K. Gene therapy for the hemophilias. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(18):9973–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gouw SC, van den Berg HM, Oldenburg J, Astermark J, de Groot PG, Margaglione M, Thompson AR, van Heerde W, Boekhorst J, Miller CH, le Cessie S, van der Bom JG. F8 gene mutation type and inhibitor development in patients with severe hemophilia A: systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood. 2012;119(12):2922–34. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-379453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuddenham EG, Schwaab R, Seehafer J, Millar DS, Gitschier J, Higuchi M, Bidichandani S, Connor JM, Hoyer LW, Yoshioka A, et al. Haemophilia A: database of nucleotide substitutions, deletions, insertions and rearrangements of the factor VIII gene, second edition. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4851–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sauna ZE, Lozier JN, Kasper CK, Yanover C, Nichols T, Howard TE. The intron-22-inverted F8 locus permits factor VIII synthesis: explanation for low inhibitor risk and a role for pharmacogenomics. Blood. 2015;125(2):223–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-530113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payne AB, Miller CH, Kelly FM, Michael Soucie J, Craig Hooper W. The CDC Hemophilia A Mutation Project (CHAMP) mutation list: a new online resource. Hum Mutat. 2013;34(2):E2382–91. doi: 10.1002/humu.22247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Repesse Y, Slaoui M, Ferrandiz D, Gautier P, Costa C, Costa JM, Lavergne JM, Borel-Derlon A. Factor VIII (FVIII) gene mutations in 120 patients with hemophilia A: detection of 26 novel mutations and correlation with FVIII inhibitor development. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(7):1469–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Astermark J, Oldenburg J, Carlson J, Pavlova A, Kavakli K, Berntorp E, Lefvert AK. Polymorphisms in the TNFA gene and the risk of inhibitor development in patients with hemophilia A. Blood. 2006;108(12):3739–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Astermark J, Oldenburg J, Pavlova A, Berntorp E, Lefvert AK, Group MS. Polymorphisms in the IL10 but not in the IL1beta and IL4 genes are associated with inhibitor development in patients with hemophilia A. Blood. 2006;107(8):3167–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Astermark J, Wang X, Oldenburg J, Berntorp E, Lefvert AK, Group MS. Polymorphisms in the CTLA-4 gene and inhibitor development in patients with severe hemophilia A. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(2):263–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franchini M, Coppola A, Mengoli C, Rivolta GF, Riccardi F, Minno GD, Tagliaferri A, ad hoc Study G. Blood Group O Protects against Inhibitor Development in Severe Hemophilia A Patients. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2017;43(1):69–74. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1592166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Suggests that severe HA patients with Blood Group O are at lowest risk for high-titer FVIII inhibitor development, independent of F8 mutation

- 18.Gunasekera D, Ettinger RA, Nakaya Fletcher S, James EA, Liu M, Barrett JC, Withycombe J, Matthews DC, Epstein MS, Hughes RJ, Pratt KP, Personalized Approaches to Therapies for Hemophilia Study I. Factor VIII gene variants and inhibitor risk in African American hemophilia A patients. Blood. 2015;126(7):895–904. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-599365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gouw SC, van der Bom JG, Marijke van den Berg H. Treatment-related risk factors of inhibitor development in previously untreated patients with hemophilia A: the CANAL cohort study. Blood. 2007;109(11):4648–54. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-056291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maclean PS, Richards M, Williams M, Collins P, Liesner R, Keeling DM, Yee T, Will AM, Young D, Chalmers EA, Paediatric Working Party of U. Treatment related factors and inhibitor development in children with severe haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2011;17(2):282–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcucci M, Mancuso ME, Santagostino E, Kenet G, Elalfy M, Holzhauer S, Bidlingmaier C, Escuriola Ettingshausen C, Iorio A, Nowak-Gottl U. Type and intensity of FVIII exposure on inhibitor development in PUPs with haemophilia A. A patient-level meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113(5):958–67. doi: 10.1160/TH14-07-0621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Velzen AS, Eckhardt CL, Peters M, Leebeek FWG, Escuriola-Ettingshausen C, Hermans C, Keenan R, Astermark J, Male C, Peerlinck K, le Cessie S, van der Bom JG, Fijnvandraat K. Intensity of factor VIII treatment and the development of inhibitors in non-severe hemophilia A patients: results of the INSIGHT case-control study. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15(7):1422–9. doi: 10.1111/jth.13711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Shows that high dose FVIII treatment (>45IU/kg/ED) and elective surgery is associated with increased risk of FVIII inhibitor development in non-severe HA patients

- 23.Margaglione M, Intrieri M. Genetic Risk Factors and Inhibitor Development in Hemophilia: What Is Known and Searching for the Unknown. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2018. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1660816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peyvandi F, Cannavo A, Garagiola I, Palla R, Mannucci PM, Rosendaal FR, sippet study g. Timing and severity of inhibitor development in recombinant versus plasma-derived factor VIII concentrates: a SIPPET analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16(1):39–43. doi: 10.1111/jth.13888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Reports higher prevalence of high-titer FVIII inhibitors in patients receiving recombinant FVIII when compared to plasma-derived FVIII

- 25.Peyvandi F, Mannucci PM, Garagiola I, El-Beshlawy A, Elalfy M, Ramanan V, Eshghi P, Hanagavadi S, Varadarajan R, Karimi M, Manglani MV, Ross C, Young G, Seth T, Apte S, Nayak DM, Santagostino E, Mancuso ME, Sandoval Gonzalez AC, Mahlangu JN, Bonanad Boix S, Cerqueira M, Ewing NP, Male C, Owaidah T, Soto Arellano V, Kobrinsky NL, Majumdar S, Perez Garrido R, Sachdeva A, Simpson M, Thomas M, Zanon E, Antmen B, Kavakli K, Manco-Johnson MJ, Martinez M, Marzouka E, Mazzucconi MG, Neme D, Palomo Bravo A, Paredes Aguilera R, Prezotti A, Schmitt K, Wicklund BM, Zulfikar B, Rosendaal FR. A Randomized Trial of Factor VIII and Neutralizing Antibodies in Hemophilia A. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(21):2054–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Michele DM, Gibb C, Lefkowitz JM, Ni Q, Gerber LM, Ganguly A. Severe and moderate haemophilia A and B in US females. Haemophilia. 2014;20(2):e136–43. doi: 10.1111/hae.12364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daidone V, Galletta E, Bertomoro A, Casonato A. The Bleeding Assessment Tool and laboratory data in the characterisation of a female with inherited haemophilia A. Blood Transfus. 2018;16(1):114–7. doi: 10.2450/2016.0132-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Surin VL, Salomashkina VV, Pshenichnikova OS, Perina FG, Bobrova ON, Ershov VI, Budanova DA, Gadaev IY, Konyashina NI, Zozulya NI. New Missense Mutation His2026Arg in the Factor VIII Gene Was Revealed in Two Female Patients with Clinical Manifestation of Hemophilia A. Russian Journal of Genetics. 2018;54(6):712–6. doi: 10.1134/s102279541806011x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.David D, Morais S, Ventura C, Campos M. Female haemophiliac homozygous for the factor VIII intron 22 inversion mutation, with transcriptional inactivation of one of the factor VIII alleles. Haemophilia. 2003;9(1):125–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chowdary P, Fosbury E, Riddell A, Mathias M. Therapeutic and routine prophylactic properties of rFactor VIII Fc (efraloctocog alfa, Eloctate((R))) in hemophilia A. J Blood Med. 2016;7:187–98. doi: 10.2147/JBM.S80814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunn AL, Ahuja SP, Mullins ES. Real-world experience with use of Antihemophilic Factor (Recombinant), PEGylated for prophylaxis in severe haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2018;24(3):e84–e92. doi: 10.1111/hae.13403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leksa NC, Chiu PL, Bou-Assaf GM, Quan C, Liu Z, Goodman AB, Chambers MG, Tsutakawa SE, Hammel M, Peters RT, Walz T, Kulman JD. The structural basis for the functional comparability of factor VIII and the long-acting variant recombinant factor VIII Fc fusion protein. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15(6):1167–79. doi: 10.1111/jth.13700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mullins ES, Stasyshyn O, Alvarez-Roman MT, Osman D, Liesner R, Engl W, Sharkhawy M, Abbuehl BE. Extended half-life pegylated, full-length recombinant factor VIII for prophylaxis in children with severe haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2017;23(2):238–46. doi: 10.1111/hae.13119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shah A, Coyle T, Lalezari S, Fischer K, Kohlstaedde B, Delesen H, Radke S, Michaels LA. BAY 94–9027, a PEGylated recombinant factor VIII, exhibits a prolonged half-life and higher area under the curve in patients with severe haemophilia A: Comprehensive pharmacokinetic assessment from clinical studies. Haemophilia. 2018. doi: 10.1111/hae.13561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bjorkman S, Folkesson A, Jonsson S. Pharmacokinetics and dose requirements of factor VIII over the age range 3–74 years: a population analysis based on 50 patients with long-term prophylactic treatment for haemophilia A. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65(10):989–98. doi: 10.1007/s00228-009-0676-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cafuir LA, Kempton CL. Current and emerging factor VIII replacement products for hemophilia A. Ther Adv Hematol. 2017;8(10):303–13. doi: 10.1177/2040620717721458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ● Reviews recombinant FVIII variants, FVIII orthologs, and FVIII gene therapy as candidate products for the optimized treatment of HA in the clinic

- 37.Zhou ZY, Koerper MA, Johnson KA, Riske B, Baker JR, Ullman M, Curtis RG, Poon JL, Lou M, Nichol MB. Burden of illness: direct and indirect costs among persons with hemophilia A in the United States. J Med Econ. 2015;18(6):457–65. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2015.1016228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D’Angiolella LS, Cortesi PA, Rocino A, Coppola A, Hassan HJ, Giampaolo A, Solimeno LP, Lafranconi A, Micale M, Mangano S, Crotti G, Pagliarin F, Cesana G, Mantovani LG. The socioeconomic burden of patients affected by hemophilia with inhibitors. Eur J Haematol. 2018. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pasi KJ, Rangarajan S, Georgiev P, Mant T, Creagh MD, Lissitchkov T, Bevan D, Austin S, Hay CR, Hegemann I, Kazmi R, Chowdary P, Gercheva-Kyuchukova L, Mamonov V, Timofeeva M, Soh CH, Garg P, Vaishnaw A, Akinc A, Sorensen B, Ragni MV. Targeting of Antithrombin in Hemophilia A or B with RNAi Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(9):819–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1616569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gruppo RA, Malan D, Kapocsi J, Nemes L, Hay CRM, Boggio L, Chowdary P, Tagariello G, von Drygalski A, Hua F, Scaramozza M, Arkin S, Marzeptacog alfa Study Group I. Phase 1, single-dose escalating study of marzeptacog alfa (activated), a recombinant factor VIIa variant, in patients with severe hemophilia. J Thromb Haemost. 2018. doi: 10.1111/jth.14247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scott LJ, Kim ES. Emicizumab-kxwh: First Global Approval. Drugs. 2018;78(2):269–74. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0861-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uchida N, Sambe T, Yoneyama K, Fukazawa N, Kawanishi T, Kobayashi S, Shima M. A first-in-human phase 1 study of ACE910, a novel factor VIII-mimetic bispecific antibody, in healthy subjects. Blood. 2016;127(13):1633–41. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-650226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mahlangu J, Oldenburg J, Paz-Priel I, Negrier C, Niggli M, Mancuso ME, Schmitt C, Jimenez-Yuste V, Kempton C, Dhalluin C, Callaghan MU, Bujan W, Shima M, Adamkewicz JI, Asikanius E, Levy GG, Kruse-Jarres R. Emicizumab Prophylaxis in Patients Who Have Hemophilia A without Inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(9):811–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ● Reports emicizumab therapy can be administered subcutaneously every 2 weeks and leads to significantly lower bleeding frequencies when compared to FVIII prophylaxis in HA

- 44.Lenting PJ, Denis CV, Christophe OD. Emicizumab, a bispecific antibody recognizing coagulation factors IX and X: how does it actually compare to factor VIII? Blood. 2017;130(23):2463–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-08-801662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Langer AL, Etra A, Aledort L. Evaluating the safety of emicizumab in patients with hemophilia A. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2018. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2019.1551356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chapin JC, Monahan PE. Gene Therapy for Hemophilia: Progress to Date. BioDrugs. 2018;32(1):9–25. doi: 10.1007/s40259-017-0255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rangarajan S, Walsh L, Lester W, Perry D, Madan B, Laffan M, Yu H, Vettermann C, Pierce GF, Wong WY, Pasi KJ. AAV5-Factor VIII Gene Transfer in Severe Hemophilia A. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(26):2519–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ● Phase I/II dose escalation study showed normal FVIII:C levels up to one year in severe HA patients who received a single F8 injection via AAV vector

- 48.High KA, George LA, Eyster E, Sullivan SK, Ragni MV, Croteau SE, Samelson-Jones BJ, Evans M, Joseney-Antoine M, Macdougall A, Kadosh J, Runoski AR, Campbell-Baird C, Douglas K, Tompkins S, Hait H, Couto LB, Eaton Bassiri A, Valentino LA, Carr ME, Hui DJ, Wachtel K, Takefman D, Mingozzi F, Anguela XM, Reape KB. A Phase 1/2 trial of investigational SPK-8011 in hemophilia A demonstrates durable expression and prevention of bleeds. Blood. 2018;132:487. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Machin N, Ragni MV, Smith KJ. Gene therapy in hemophilia A: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Blood Adv. 2018;2(14):1792–8. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018021345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calcedo R, Morizono H, Wang L, McCarter R, He J, Jones D, Batshaw ML, Wilson JM. Adeno-associated virus antibody profiles in newborns, children, and adolescents. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18(9):1586–8. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05107-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Calcedo R, Wilson JM. Humoral Immune Response to AAV. Front Immunol. 2013;4:341. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li C, Narkbunnam N, Samulski RJ, Asokan A, Hu G, Jacobson LJ, Manco-Johnson MJ, Monahan PE, Joint Outcome Study I. Neutralizing antibodies against adeno-associated virus examined prospectively in pediatric patients with hemophilia. Gene Ther. 2012;19(3):288–94. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fitzpatrick Z, Leborgne C, Barbon E, Masat E, Ronzitti G, van Wittenberghe L, Vignaud A, Collaud F, Charles S, Simon Sola M, Jouen F, Boyer O, Mingozzi F. Influence of Pre-existing Anti-capsid Neutralizing and Binding Antibodies on AAV Vector Transduction. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2018;9:119–29. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Colella P, Ronzitti G, Mingozzi F. Emerging Issues in AAV-Mediated In Vivo Gene Therapy. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2018;8:87–104. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacKenzie TC, David AL, Flake AW, Almeida-Porada G. Consensus statement from the first international conference for in utero stem cell transplantation and gene therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:15. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Almeida-Porada G, Waddington SN, Chan JKY, Peranteau WH, MacKenzie T, Porada CD. In Utero Gene Therapy Consensus Statement from the IFeTIS. Mol Ther. 2019;27(4):705–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ● States the key criteria for the consideration of in utero gene transfer in human patients

- 57.Flake AW, Roncarolo MG, Puck JM, Almeida-Porada G, Evans MI, Johnson MP, Abella EM, Harrison DD, Zanjani ED. Treatment of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency by in utero transplantation of paternal bone marrow. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(24):1806–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612123352404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ● Early clinical report of X-SCID successfully treated prior to birth via in utero paternal donor cell transplantation

- 58.Wengler GS, Lanfranchi A, Frusca T, Verardi R, Neva A, Brugnoni D, Giliani S, Fiorini M, Mella P, Guandalini F, Mazzolari E, Pecorelli S, Notarangelo LD, Porta F, Ugazio AG. In-utero transplantation of parental CD34 haematopoietic progenitor cells in a patient with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (SCIDXI). Lancet. 1996;348(9040):1484–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Westgren M, Ringden O, Bartmann P, Bui TH, Lindton B, Mattsson J, Uzunel M, Zetterquist H, Hansmann M. Prenatal T-cell reconstitution after in utero transplantation with fetal liver cells in a patient with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(2):475–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mannucci PM, Tuddenham EG. The hemophilias--from royal genes to gene therapy. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(23):1773–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Balak DM, Gouw SC, Plug I, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, Vriends AH, Van Diemen-Homan JE, Rosendaal FR, van der Bom JG. Prenatal diagnosis for haemophilia: a nationwide survey among female carriers in the Netherlands. Haemophilia. 2012;18(4):584–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chalmers E, Williams M, Brennand J, Liesner R, Collins P, Richards M. Guideline on the management of haemophilia in the fetus and neonate. Br J Haematol. 2011;154(2):208–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dai J, Lu Y, Ding Q, Wang H, Xi X, Wang X. The status of carrier and prenatal diagnosis of haemophilia in China. Haemophilia. 2012;18(2):235–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deka D, Dadhwal V, Roy KK, Malhotra N, Vaid A, Mittal S. Indications of 1342 fetal cord blood sampling procedures performed as an integral part of high risk pregnancy care. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2012;62(1):20–4. doi: 10.1007/s13224-012-0152-x152 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Massaro JD, Wiezel CE, Muniz YC, Rego EM, de Oliveira LC, Mendes-Junior CT, Simoes AL. Analysis of five polymorphic DNA markers for indirect genetic diagnosis of haemophilia A in the Brazilian population. Haemophilia. 2011;17(5):e936–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peyvandi F Carrier detection and prenatal diagnosis of hemophilia in developing countries. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2005;31(5):544–54. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-922226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shetty S, Ghosh K, Jijina F. First-trimester prenatal diagnosis in haemophilia A and B families--10 years experience from a centre in India. Prenat Diagn. 2006;26(11):1015–7. doi: 10.1002/pd.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Silva Pinto C, Fidalgo T, Salvado R, Marques D, Goncalves E, Martinho P, Markoff A, Martins N, Leticia Ribeiro M. Molecular diagnosis of haemophilia A at Centro Hospitalar de Coimbra in Portugal: study of 103 families--15 new mutations. Haemophilia. 2012;18(1):129–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sasanakul W, Chuansumrit A, Ajjimakorn S, Krasaesub S, Sirachainan N, Chotsupakarn S, Kadegasem P, Rurgkhum S. Cost-effectiveness in establishing hemophilia carrier detection and prenatal diagnosis services in a developing country with limited health resources. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2003;34(4):891–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tsui NB, Kadir RA, Chan KC, Chi C, Mellars G, Tuddenham EG, Leung TY, Lau TK, Chiu RW, Lo YM. Noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of hemophilia by microfluidics digital PCR analysis of maternal plasma DNA. Blood. 2011;117(13):3684–91. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-310789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hussein IR, El-Beshlawy A, Salem A, Mosaad R, Zaghloul N, Ragab L, Fayek H, Gaber K, El-Ekiabi M. The use of DNA markers for carrier detection and prenatal diagnosis of haemophilia A in Egyptian families. Haemophilia. 2008;14(5):1082–7. doi: HAE1779 [pii] 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Davey MG, Riley JS, Andrews A, Tyminski A, Limberis M, Pogoriler JE, Partridge E, Olive A, Hedrick HL, Flake AW, Peranteau WH. Induction of Immune Tolerance to Foreign Protein via Adeno-Associated Viral Vector Gene Transfer in Mid-Gestation Fetal Sheep. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0171132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ● Reports in utero gene transfer in fetal sheep using AAV vector encoding GFP and shows the induction of immune tolerance to the vector-encoded protein

- 73.Takahashi K, Endo M, Miyoshi T, Tsuritani M, Shimazu Y, Hosoda H, Saga K, Tamai K, Flake AW, Yoshimatsu J, Kimura T. Immune tolerance induction using fetal directed placental injection in rodent models: a murine model. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0123712. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Peranteau WH, Hayashi S, Abdulmalik O, Chen Q, Merchant A, Asakura T, Flake AW. Correction of murine hemoglobinopathies by prenatal tolerance induction and postnatal nonmyeloablative allogeneic BM transplants. Blood. 2015;126(10):1245–54. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-636803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Colletti E, Lindstedt S, Park PJ, Almeida-Porada G, Porada CD. Early fetal gene delivery utilizes both central and peripheral mechanisms of tolerance induction. Exp Hematol. 2008;36(7):816–22. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Waddington SN, Nivsarkar MS, Mistry AR, Buckley SM, Kemball-Cook G, Mosley KL, Mitrophanous K, Radcliffe P, Holder MV, Brittan M, Georgiadis A, Al-Allaf F, Bigger BW, Gregory LG, Cook HT, Ali RR, Thrasher A, Tuddenham EG, Themis M, Coutelle C. Permanent phenotypic correction of hemophilia B in immunocompetent mice by prenatal gene therapy. Blood. 2004;104(9):2714–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tran ND, Porada CD, Almeida-Porada G, Glimp HA, Anderson WF, Zanjani ED. Induction of stable prenatal tolerance to beta-galactosidase by in utero gene transfer into preimmune sheep fetuses. Blood. 2001;97(11):3417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kaveri SV, Dasgupta S, Andre S, Navarrete AM, Repesse Y, Wootla B, Lacroix-Desmazes S. Factor VIII inhibitors: role of von Willebrand factor on the uptake of factor VIII by dendritic cells. Haemophilia. 2007;13 Suppl 5:61–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kempton CL, Meeks SL. Toward optimal therapy for inhibitors in hemophilia. Blood. 2014;124(23):3365–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-577643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Porada CD, Almeida-Porada G. Treatment of Hemophilia A in Utero and Postnatally using Sheep as a Model for Cell and Gene Delivery. J Genet Syndr Gene Ther. 2012;S1. doi: 10.4172/2157-7412.S1-011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Porada CD, Stem C, Almeida-Porada G. Gene therapy: the promise of a permanent cure. N C Med J. 2013;74(6):526–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Porada CD, Rodman C, Ignacio G, Atala A, A-P G. Hemophilia A: An Ideal Disease to Correct in Utero. Frontiers in Pharmacology; Integrative and Regenerative Pharmacology. 2014;In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hassan HJ, Leonardi A, Chelucci C, Mattia G, Macioce G, Guerriero R, Russo G, Mannucci PM, Peschle C. Blood coagulation factors in human embryonic-fetal development: preferential expression of the FVII/tissue factor pathway. Blood. 1990;76(6):1158–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ● Shows that early during human fetal development, Factor X becomes activated predominantly via the tissue factor pathway, and largely independent of the FIXa/FVIIIa phospholipid complex

- 84.Manco-Johnson MJ. Development of hemostasis in the fetus. Thromb Res. 2005;115 Suppl 1:55–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ong K, Horsfall W, Conway EM, Schuh AC. Early embryonic expression of murine coagulation system components. Thromb Haemost. 2000;84(6):1023–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Touraine JL. Transplantation of human fetal liver cells into children or human fetuses In: Bhattacharya N, Stubblefield P, editors. Human Fetal Tissue Transplantation. London: Springer Verlag International; 2013. p. 205–18. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Almeida-Porada G, Atala A, Porada CD. In utero stem cell transplantation and gene therapy: rationale, history, and recent advances toward clinical application. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2016;5:16020. doi: 10.1038/mtm.2016.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Porada CD, Rodman C, Ignacio G, Atala A, Almeida-Porada G. Hemophilia A: an ideal disease to correct in utero. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:276. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rechavi E, Lev A, Lee YN, Simon AJ, Yinon Y, Lipitz S, Amariglio N, Weisz B, Notarangelo LD, Somech R. Timely and spatially regulated maturation of B and T cell repertoire during human fetal development. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(276):276ra25. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Maloney S, Smith A, Furst DE, Myerson D, Rupert K, Evans PC, Nelson JL. Microchimerism of maternal origin persists into adult life. J Clin Invest. 1999;104(1):41–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI6611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ● First study that demonstrated the long-term presence of HLA-disparate maternal cells in healthy offspring

- 91.Jonsson AM, Uzunel M, Gotherstrom C, Papadogiannakis N, Westgren M. Maternal microchimerism in human fetal tissues. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(3):325 e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Stevens AM, Hermes HM, Kiefer MM, Rutledge JC, Nelson JL. Chimeric maternal cells with tissue-specific antigen expression and morphology are common in infant tissues. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2009;12(5):337–46. doi: 10.2350/08-07-0499.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McGovern N, Shin A, Low G, Low D, Duan K, Yao LJ, Msallam R, Low I, Shadan NB, Sumatoh HR, Soon E, Lum J, Mok E, Hubert S, See P, Kunxiang EH, Lee YH, Janela B, Choolani M, Mattar CNZ, Fan Y, Lim TKH, Chan DKH, Tan KK, Tam JKC, Schuster C, Elbe-Burger A, Wang XN, Bigley V, Collin M, Haniffa M, Schlitzer A, Poidinger M, Albani S, Larbi A, Newell EW, Chan JKY, Ginhoux F. Human fetal dendritic cells promote prenatal T-cell immune suppression through arginase-2. Nature. 2017;546(7660):662–6. doi: 10.1038/nature22795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ● Demonstrates that human fetal dendritic cells can promote adaptive immune cell suppression during gestational development via arginase-2.

- 94.Flake AW, Zanjani ED. In utero hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: ontogenic opportunities and biologic barriers. Blood. 1999;94(7):2179–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Westgren M In utero stem cell transplantation. Semin Reprod Med. 2006;24(5):348–57. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-952156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Touraine JL, Raudrant D, Royo C, Rebaud A, Roncarolo MG, Souillet G, Philippe N, Touraine F, Betuel H. In-utero transplantation of stem cells in bare lymphocyte syndrome. Lancet. 1989;1(8651):1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Flake AW, Roncarolo MG, Puck JM, Almeida-Porada G, Evans MI, Johnson MP, Abella EM, Harrison DD, Zanjani ED. Treatment of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency by in utero transplantation of paternal bone marrow. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(24):1806–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612123352404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Le Blanc K, Gotherstrom C, Ringden O, Hassan M, McMahon R, Horwitz E, Anneren G, Axelsson O, Nunn J, Ewald U, Norden-Lindeberg S, Jansson M, Dalton A, Astrom E, Westgren M. Fetal mesenchymal stem-cell engraftment in bone after in utero transplantation in a patient with severe osteogenesis imperfecta. Transplantation. 2005;79(11):1607–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gotherstrom C, Westgren M, Shaw SW, Astrom E, Biswas A, Byers PH, Mattar CN, Graham GE, Taslimi J, Ewald U, Fisk NM, Yeoh AE, Lin JL, Cheng PJ, Choolani M, Le Blanc K, Chan JK. Pre- and postnatal transplantation of fetal mesenchymal stem cells in osteogenesis imperfecta: a two-center experience. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014;3(2):255–64. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Peranteau WH, Endo M, Adibe OO, Flake AW. Evidence for an immune barrier after in utero hematopoietic-cell transplantation. Blood. 2007;109(3):1331–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-018606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]