Abstract

We read the recent article in Psychology of Sport and Exercise by Liu et al. (“A randomized controlled trial of coordination exercise on cognitive function in obese adolescents”) with great interest. Our interest in the article stemmed from the extraordinary differences in obesity-related outcomes reported in response to a rope-jumping intervention. We requested the raw data from the authors to confirm the results and, after the journal editors reinforced our request, the authors graciously provided us with their data. We share our evaluation of the original data herein, which includes concerns that weight and BMI loss by the intervention appears extraordinary in both magnitude and aspects of the distributions. We request that the authors address our findings by providing explanations of the extraordinary data or correcting any errors that may have occurred in the original report, as appropriate.

Keywords: effect size, mathematical model, adolescent obesity, weight loss

1. Introduction

A recent article in Psychology of Sport and Exercise, “A randomized controlled trial of coordination exercise on cognitive function in obese adolescents,” by Liu et al. (Liu et al., 2018) contains extraordinary results for the reported outcomes. The BMI change data and the baseline mean stature reported by Liu et al. suggested that subjects would have lost on the order of 5 kg from jumping rope. This magnitude of effect is on par with more intensive lifestyle or pharmacological obesity interventions, and thus seemed extraordinary to us.

Because we wanted to study these results more closely, we sent a letter to both the authors, and subsequently the journal editor, to request the raw data. At the editors’ request, the authors graciously shared the data. First, we examined the reported treatment effect on weight loss in the context of a validated mathematical model of energy balance (“Estimating plausibility of weight change”). Although this energy balance model is widely accepted as a useful tool for predicting and estimating body composition, those outputs are dependent on parameter settings and model assumptions such as no behavioral compensation (note: As compensation of exercise, it is known that exercise upregulates appetite (Thivel, Finlayson, & Blundell, 2019). Our assumption is favorable to the results of Liu et al.). Our assumptions and inputs into this model might not fully capture the actual conditions of Liu et al.’s study. Therefore, we also assessed the plausibility of the reported results by computing effect sizes and plotting distributions of weight loss by comparison with a weight loss study of adolescents with obesity (data provided by Dr. Yanovski, one of the coauthors of this report; “Extraordinary effect size and distribution for weight loss”).

We further investigated whether the raw data provided by the authors seemed commensurate with expectations (“Investigating Data”).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of data and key variables

Data from Liu et al

The deidentified data were provided by Dr. Chang, one of the corresponding authors, on March 5, 2018, in an SPSS file format, “English.sav”. The file was converted to CSV file format and analyzed with the statistical software R (version 3.4.1). As described in the article, “Eighty obese adolescents were randomly assigned to a 12-week coordination exercise program or a waitlist control group and data from 70 participants (n=35 for each group) were analyzed.” The adolescents’ mean age was 14.06 (SD=0.83) years and 30 (42.86%) were female. The key variables sent to us in the data file included:

(A1) Height (cm) before the exercise program

(A2) Weight (kg) before the exercise program

(A3) BMI before the exercise program

(B1) Weight (kg) after the exercise program

(B2) BMI after the exercise program

Data were available for both the Exercise and the Control groups. Height after the exercise program was not reported in the file. The process of measurement was not described in the article except that “[a] trained experimenter masked to group allocation administered the primary and secondary outcome measures.” In the SPSS data file, the data were represented with 1 decimal place for height and weight and 2 decimal places for BMI. The published article did not specify how height and weight were measured or recorded.

Data from Condarco et al

One of us (Dr. Yanovski) also provided data from another weight loss study (NCT00001723) for comparative purposes; this was a 6-month drug (orlistat) versus placebo randomized controlled trial (RCT) in which the adolescents (all with severe obesity) also received intensive behavioral therapy, diet, and exercise prescription (Condarco et al., 2013). The rationale for using this data set for comparison was: 1) it was a weight loss study; 2) it was conducted in adolescents; 3) we wanted to compare Liu et al. to real-world, rather than hypothetical or simulated, variability and pre-post correlations; 4) it was another study with a large effect size (a drug effect plus a behavioral intervention is larger than that of a behavioral intervention alone in general); 5) the intervention was of similar length (12 weeks); 6) the study population was of mixed sex; and 7) the study population was of similar age. We believe that using an existing data set allows us to not only compare against theoretical anomalies (e.g., the distribution of weight change) but also compare with an empirical example. Note that Condarco et al.’s data represents only one weight-loss study focusing on adolescents with obesity, and should be considered as a comparative case study that was available to us. We searched for other available datasets based on the criteria above, but only Condarco et al.’s data met the criteria and were immediately available. Although the study has not been published yet, the summary statistics of the data are available online (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00001723). The sample size was 180 (93 and 87 children were allocated to drug and placebo groups, respectively). Their mean age was 14.56 (SD:1.41) years and 118 (65.6%) were female. The following variables were included:

(A) Weight (kg) before the RCT

(B) Weight (kg) at week 12 during the RCT

All data were recorded to 1 decimal place. Note that although the RCT went to 6 months, we used the 12-week weight data for analysis to coincide with the length of the Liu et al. trial.

2.2. Computational environment for the analyses

All analyses except computation of energy intake and expected weight loss (“Estimating plausibility of weight change”) were performed with the statistical computing software R 3.4.1; its package ‘effsize’ (version 0.7.0) was used to compute Cohen’s d.

3. Results

3.1. Primary concerns

e have assessed the plausibility of the weight change results from two aspects: 1) whether the magnitude of weight loss in the article is consistent with what is expected from a validated mathematical model, and 2) whether the effect size (Cohen’s d) in weight loss and weight loss distributions of the Exercise and Control groups are plausible.

Estimating plausibility of weight change

The change in BMI across a 12-week rope jumping intervention seemed larger than we would have expected from our experience. To quantify our expectations, we calculated a likely upper bound (but still reasonable) estimate of the expected energy expenditure and expected weight change from the intervention. We used the estimated energy expenditure of rope jumping in children reported by Harrell et al. (Harrell et al., 2005). We used the highest average oxygen consumption and subtracted the lowest resting energy expenditure (i.e., maximizing estimated energy expenditure among values reported by Harell et al. in order to make the estimated energy expenditure favorable to the results of Liu’s study and to address the uncertainty of the estimated values due to the small sample size of Harrell’s study) to calculate incremental energy expenditure from estimated oxygen consumption. We intentionally avoid using METS as it is not available for this age group. Although the children jumped rope for only 40 min in the study by Liu et al., we estimated energy expenditure for 60 min of rope jumping, again to supply a reasonable upper bound of energy expenditure in a direction that would favor Liu et al.’s results. We also used an upper bound of 5 kcal per L of O2 consumption corresponding to primarily carbohydrate oxidation. Finally, we used the approximate average weight of the children in Liu et al., which was 75 kg. The energy expenditure associated with the program is computed as follows:

With two sessions every 7 days, this results in an average increase in energy expenditure of approximately 201 kcal per day.

We used a validated mathematical model of childhood energy balance dynamics (Hall, Butte, Swinburn, & Chow, 2013) to calculate the additional energy needed to generate the measured baseline weight of 74.3 kg at 14 years of age compared to the standard reference intake. Such a child is estimated to require about 770 kcal/d of energy intake above reference. If the Control group maintained their typical behaviors, the model predicted that after 12 weeks the children would have gained approximately 1.6 kg from natural growth. Even if children in the Exercise group did not compensate for their additional exercise energy expenditure by eating more [which adults generally do (Dhurandhar et al., 2015)], the intervention would only be anticipated to cause a very moderate weight loss of approximately 0.52 kg. The subjects in the Exercise group from Liu et al. were reported to have lost 4.39 (SD:3.04) kg (Table 1). This magnitude of weight loss is extraordinary compared with the estimated amount of weight loss (0.52 kg). To confirm the mathematical model in a similar experiment, we compared the predicted to the actual weight loss of an exercise study with similar intervention (“Aerobic exercise training was … conducted 4 days/week for 12 weeks. Each session consisted of 5 min of warming up, 30–40 min of rope skipping (the energy expenditure was 300–400 kcal per exercise session...”) (Lee, Shin, Lee, Jun, & Song, 2010). The model-predicted weight loss using the upper limit of 230 kcal/d (=400 kcal per session, 4 sessions per week) was 2.2 kg compared with the observed weight loss 2.5 kg, an underestimation of weight loss of about 0.3 kg, compared to a difference of about 3.9 kg between the predicted and observed values for Liu et al. Though these calculations required multiple assumptions, the assumptions were in the direction favoring the results Liu et al. reported; differences in these assumptions are unlikely to produce an order of magnitude difference in weight change unless there were substantial differences in other aspects of the Exercise group’s behaviors (e.g., large increases in spontaneous activity, large decreases in energy intake, significant positive change in height).

Table 1.

Change in BMI, weight, and height after the exercise program for Liu et al.

| Exercise | Control | Between-group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Change | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Change | p-value* | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.01 (3.03) | 25.99 (2.67) | −2.01 (1.33) | 27.92 (3.29) | 28.16 (3.34) | 0.24 (0.52) | < 0.001 |

| Weight, kg | 74.33 (12.16) | 69.93 (11.15) | −4.39 (3.04) | 75.86 (13.95) | 76.95 (14.13) | 1.09 (1.39) | < 0.001 |

| Height, cm | 162.45 (5.73) | 163.62 (6.15)** | 1.17 (1.19) | 164.4 (8.32) | 164.85 (8.31)** | 0.44 (0.64) | 0.002 |

Note. Values are mean (SD).

After confirming the variances were significantly different between the groups (F-test, P<0.001 for each variables), two-sided unpaired Welch’s t-test was used to test the difference in pre-post change between the groups.

Height was back-calculated at post-test based on reported BMI.

Extraordinary Effect Size and Distribution for Weight Loss

The weight loss in the Exercise group seems extraordinary given 1) the low intensity of the intervention, 2) that every single person in the Exercise group lost weight (Fig. 1A), and 3) that the distributions for the groups barely overlapped (Fig. 2A). We reiterate that all individuals in the Exercise group lost weight (three persons lost more than 10 kg), whereas no one in the Control group lost more than 3 kg. It is unusual to observe distributions of weight loss with such little overlap between groups. A difference in means (5.48 kg) this large relative to the respective variability (standard deviation) corresponds to a Cohen’s d effect size of 2.32, which is exceedingly rare (Abelson, 1985; Abelson & John, 1995; Sawilowsky, 2009). Even compared with the mean difference in weight loss between groups among typical adolescent exercise studies (duration of intervention varies; 6 weeks to 6 months), which is 0.74 kg (95% CI: [0.30, 1.18]), the observed difference (5.48 kg) is extraordinary (Kelley, Kelley, & Pate, 2014). Furthermore, a systematic review of meta-analysis (meta-meta-analysis, N=17) of exercise studies targeting adolescents with overweight or obesity suggested weight change after exercise programs (12 weeks or more, pooled) was −0.23 kg (95% CI: [−0.05, −0.41]), (Garcia-Hermoso, Ramirez-Velez, & Saavedra, 2018). Liu et al. report an observed mean weight change in the Exercise group of −4.39 (SD: 3.04) kg.

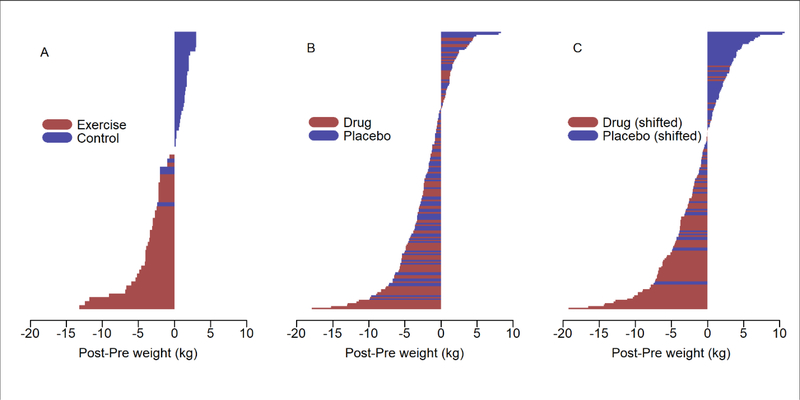

Figure 1. Horizontal bar plots of change in weight.

Panel A corresponds to Liu et al. and Panel B corresponds to Condarco et al. Panel C also corresponds to Condarco et al.’s data in which values in each group are shifted such that the means of each group match those of Liu et al., resulting in the same mean difference but maintaining the within-group variance.

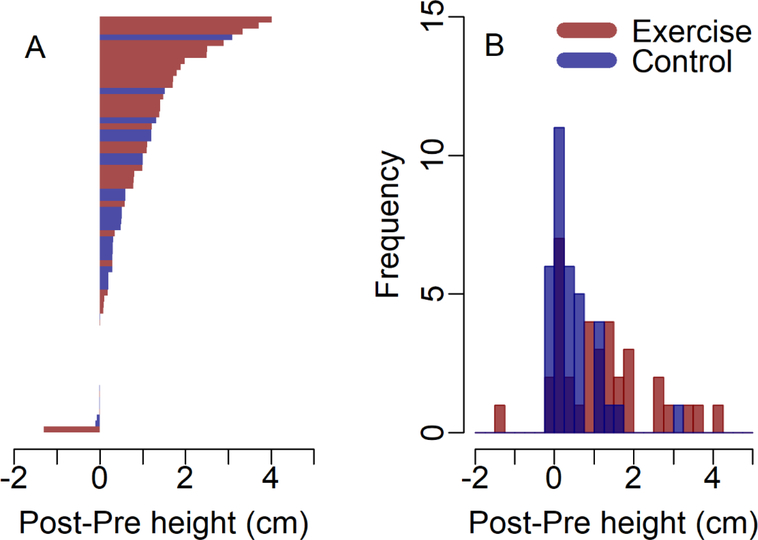

Figure 3. Plots of change in height in Liu et al., after back-calculation of data.

Panels A and B are the icicle plot and histogram of post-pre height difference. Post-Pre height=height at 12 week – height at 0 week, where, where [height=√(weight in kg/BMI)].

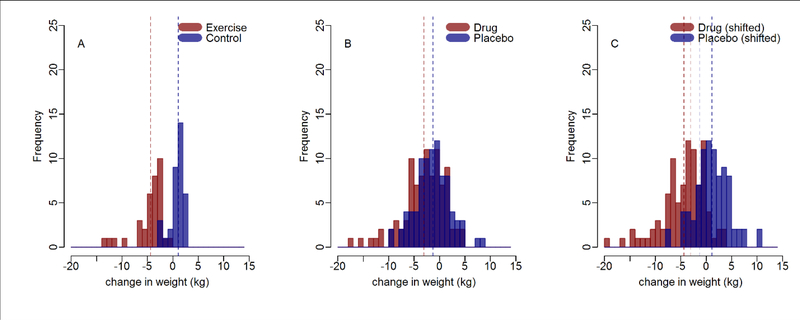

Figure 2. Histograms of change in weight.

Panel A corresponds to Liu et al. and Panel B corresponds to Condarco et al. Panel C also corresponds to Condarco et al.’s data in which values in each group are shifted such that the means of each group match those of Liu et al., resulting in the same mean difference but maintaining the within-group variance. Each dotted line corresponds to the mean of the group with the same color. The dotted lines with light color in Panel C represent the original means, identical to the dotted lines in Panel B.

To provide context in evaluating the plausibility of these distributions between two groups, we compared the weight loss distribution of this study with that of another independent adolescent weight loss study by Condarco et al. (Condarco et al., 2013).

Although the magnitude of weight loss was significantly larger in the Drug group than in the Placebo group (Table 1), we observed a large amount of overlap in the distributions of weight loss between the groups (Figure 2B). In Condarco et al., the observed Cohen’s d effect size was 0.45 with a mean difference of 1.74 kg, which is of a much more commonly observed magnitude (Table 2) than that reported by Liu et al. To evaluate whether the apparent difference in distributional overlap was simply the result of a difference in mean effect, we shifted individual values in each group from Condarco et al.’s data so that the within-group mean of observations was equal to those of Liu et al., resulting in the same mean difference but maintaining the within-group variance (see the dotted lines in Figure 2, which represent the mean of each group). Substantial overlap remains in Condarco et al.’s data, with data that more nearly follow the normal distribution for each group (Figure 1C and Figure 2C). In particular, from Figure 1B we observe at least some individuals in the Drug intervention who gained weight after the treatment period, whereas the data from Liu et al. show no one in the Exercise group gained weight. The unusually shaped and nearly nonoverlapping distributions of weight change in the Liu et al. study merit consideration.

Table 2.

Change in weight after the RCT for Condarco et al.

| Drug | Placebo | Between-group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-RCT | Post-RCT | Change | Pre-RCT | Post-RCT | Change | p-value* | |

| Change in weight, kg | 113.99 (25.37) | 110.93 (24.78) | −3.06 (4.26) | 115.34 (24.27) | 114.03 (24.67) | −1.32 (3.39) | 0.003 |

Note. Values are mean (SD).

After confirming the variances were significantly different between the groups (F-test, P=0.03), two-sided unpaired Welch’s t-test was used to test the difference in pre-post change between the groups.

4. Investigating data

We further examined the data themselves and note the following.

Curious Effect on Height Change

Curious effect on height change. Based on reported BMI and weight following the program, we back-calculated the post-intervention heights assuming the BMI values were calculated and reported correctly (see 4.3 for discrepancies in pre-intervention BMI calculation).1 First, we tested the statistical difference in BMI, weight, and height between the groups before the intervention and confirmed there were no differences (p=.91, .63, and 0.26 from Student’s t-test, respectively). Second, we compared the change-in-BMI, weight, and height after the intervention. Because variances were significantly different between groups (F-test for differences in variance, p<.001), we compared the two groups on change-in-height using a Welch-corrected, two-sided, unpaired t-test. We found that change-in-height was significantly different between groups, where participants in the Control group grew an average of 0.44 cm (SD=0.64), and participants in the Exercise group grew an average of 1.17 cm (SD=1.19, p=.002; Table 1). Because the participants were adolescents in the rapid growth phase of puberty, increasing height in 12 weeks is not surprising; however, observing a difference in growth between two groups over 12 weeks is surprising. How jumping rope twice per week may plausibly increase height merits consideration.

Peculiar Distribution of Digits after Decimal Point of Height and Weight

We noticed an unusual pattern in which about half of the values for height and weight seemed to be rounded to the nearest integer (see Table 3). We plotted histograms of the digits after the decimal point of height, weight, and BMI from Liu et al.’s study (Figure 4).

Table 3.

The four cases with the largest discrepancy between reported BMI and recalculated BMI before the exercise program (Pre-intervention value)

| Group | Reported Height | Reported Weight | Reported BMI | Recalculated BMI | Discrepancy* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise | 159.0 | 65.0 | 26.00 | 25.71 | 0.29 |

| Exercise | 175.0 | 83.4 | 27.60 | 27.23 | 0.37 |

| Exercise | 160.2 | 69.0 | 26.29 | 26.89 | 0.60 |

| Exercise | 160.0 | 78.6 | 30.00 | 30.70 | 0.70 |

Discrepancy is defined as the absolute value of reported BMI minus recalculated BMI from data provided from Liu et al.

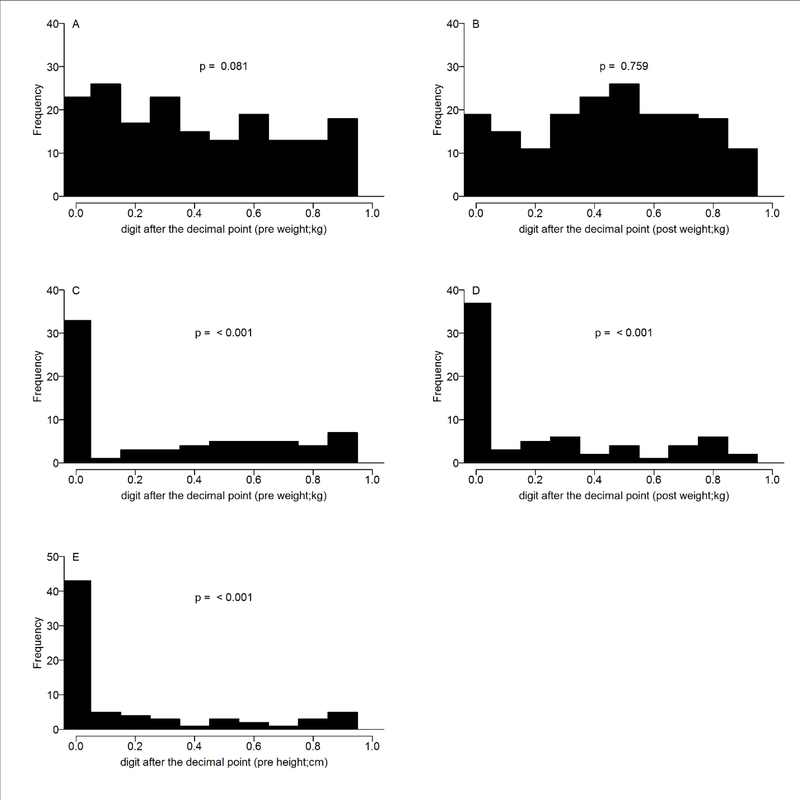

Figure 4. Histograms of the digit after the decimal point in recorded data from Condarco et al. and Liu et al.

Panels A and B correspond to Condarco et al. and Panels C-E correspond to Liu et al. P-values are computed from Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The data from Exercise and Control (or drug and placebo) groups are combined. Pre weight, pre-intervention weight; post weight, post-intervention weight; pre height, pre-intervention height.

These digits from both Liu et al. and Condarco et al. would be expected to follow a uniform distribution if the values were not rounded (Mosimann, Dahlberg, Davidian, & Krueger, 2002). Because the values are rounded to one decimal place, they are expected to follow a discrete uniform distribution (i.e., the digits can take the values in {0.0, 0.1, 0.2, …0.9} with the same probability of 1/10. A Kolmogorov- Smirnov test was used to test for departure from the discrete uniform distribution. The distributions for both pre- and post-intervention weight were not statistically significantly different from the uniform distribution for Condarco et al.’s data (p=.081 and .759, respectively; Fig. 4). However, in Liu et al.’s study, the distributions for pre- and post-intervention weight and pre-intervention height were significantly different from the uniform distribution (all P<0.001, Figure 4). The explanation for this unexpected distribution of digits should be addressed.

Mathematical Discrepancy in BMI

To check the process of calculation of BMI (variable A3), we recalculated BMI as kg/m2 using reported height (variable A1) and weight (variable A2) before the exercise intervention. Because height was not reported after the program, the discrepancy could only be precisely tested for pre-intervention data. In four cases, the discrepancy in BMI values was larger than what we would expect from data rounded to two decimal places as reported (see Table 3). The reason for these discrepancies is unclear and should be explained by the authors, including clarifying 1) whether the post-intervention height was measured and 2) how the post-intervention BMI was computed.

5. Conclusion

The data of Liu et al.’s study were reanalyzed and evaluated in comparison to typical expected results combined with a study of a weight loss drug in adolescents with obesity by Condarco et al. What we found and reported here suggests that Liu et al.’s data may contain errors. We thank the authors for sharing the data and hope they will explain these findings or correct any errors that may have occurred in the original report, as appropriate.

Acknowledgement

Supported in part by NIH grants R25HL124208, R25DK099080 and Japan Society for Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI grant 18K18146. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessary those of our institutions or any other organizations.

Declaration of interest: JAY is a Commissioned Officer in the US Public Health Service (PHS). JAY is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Z1AHD00641).

References

- Abelson RP (1985). A variance explanation paradox: When a little is a lot. Psychological Bulletin, 97(1), 129. [Google Scholar]

- Abelson RP, & John WT (1995). Statistics as principled argument. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Condarco TA, Sherafat Kazemzadeh R, Mcduffie JR, Brady SM, Salaita C, Sebring NG,… Yanovski JA (2013). Long-term follow-up of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of orlistat in African-American and caucasian adolescents with obesity-related comorbid conditions. Paper presented at the The Endocrine Society’s 95th Annual Meeting and Expo, San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Dhurandhar EJ, Kaiser KA, Dawson JA, Alcorn AS, Keating KD, & Allison DB (2015). Predicting adult weight change in the real world: a systematic review and meta-analysis accounting for compensatory changes in energy intake or expenditure. Int J Obes (Lond), 39(8), 1181–1187. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Hermoso A, Ramirez-Velez R, & Saavedra JM (2018). Exercise, health outcomes, and paediatric obesity: A systematic review of meta-analyses. J Sci Med Sport. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2018.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall KD, Butte NF, Swinburn BA, & Chow CC (2013). Dynamics of childhood growth and obesity: development and validation of a quantitative mathematical model. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 1(2), 97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell JS, McMurray RG, Baggett CD, Pennell ML, Pearce PF, & Bangdiwala SI (2005). Energy costs of physical activities in children and adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 37(2), 329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley GA, Kelley KS, & Pate RR (2014). Effects of exercise on BMI z-score in overweight and obese children and adolescents: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr, 14, 225. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KJ, Shin YA, Lee KY, Jun TW, & Song W (2010). Aerobic exercise training-induced decrease in plasma visfatin and insulin resistance in obese female adolescents. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab, 20(4), 275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J-H, Alderman BL, Song T-F, Chen F-T, Hung T-M, & Chang Y-K (2018). A randomized controlled trial of coordination exercise on cognitive function in obese adolescents. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 34, 29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosimann J, Dahlberg J, Davidian N, & Krueger J (2002). Terminal Digits and the Examination of Questioned Data. Accountability in Research, 9(2), 75–92. doi: 10.1080/08989620212969 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sawilowsky SS (2009). New effect size rules of thumb. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods, 8(2), 26. [Google Scholar]

- Thivel D, Finlayson G, & Blundell JE (2019). Homeostatic and neurocognitive control of energy intake in response to exercise in pediatric obesity: a psychobiological framework. Obes Rev, 20(2), 316–324. doi: 10.1111/obr.12782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]