Abstract

Introduction:

The aim of this study was to present our 20-year experience regarding open adrenalectomy (OA) during laparoscopic era in a developing country Turkey.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective and descriptive study of patients with adrenal mass undergoing OA in the surgery department of our hospital, between January 1993 and January 2013, was carried out. All operations were performed by two surgeons.

Results:

Ninety patients who underwent OA in our clinic were reviewed retrospectively. The mean number of adrenal operations per month during this period was 0.38 ± 0.12. The patient included 35 men (38.8%) and 55 women (61.2%), with a mean age of 46.4 ± 17 years. The mean body mass index was 28.4 ± 5.25, and the mean American Society of Anesthesiologists score was 2.6 ± 0.57. The mean operative time was 88 ± 27 min. The mean maximum diameter of all the lesions was 4.8 ± 1.3 cm (range: 1.2–21 cm). The mean blood loss was 118 ± 23 ml during the operations. Postoperative complications were observed in four patients (5.5%). There was no mortality. The length of hospital stay was 6.2 ± 2.1 days. The most frequent type of the histological type was benign adenoma (48.8%).

Conclusion:

OA in a developing country is a safe method as an alternative for laparoscopic adrenalectomy which has a difficult learning curve.

Keywords: Adrenal mass, adrenalectomy, laparoscopic, open, masse adrénalienne, adrénalectomie, laparoscopie, ouverte

Résumé

Introductıon:

Le but de cette étude est de présenter nos 20 ans dæexpérience de læadrénalectomie ouverte (OA) lors de la laparoscopie dans un pays en développement.

Matériaux et méthodes:

Une étude rétrospective et descriptive a été prévue dans le service de chirurgie générale de notre hôpital, incluant des patients ayant subi entre janvier 1993 et janvier 2013 une adrénalectomie ouverte pour une masse adrrénalienne. Toutes les opérations ont été effectuées par 2 chirurgiens.

Résultats:

Quatre-vingt-dix patients qui ont subi une adrénalectomie ouverte dans notre clinique ont été évalués rétrospectivement. Le nombre moyen dæopérations adrénaliennes par mois au cours de cette période était de 0,38 ± 0,12. Læâge moyen des patients était de 46,4 ± 17 ans: 35 (38,8%) étaient des hommes et 55 (61,2%) étaient des femmes. Læindice de masse corporelle (IMC) moyen était de 28,4 ± 5,25 et le score moyen de læAmerican Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) était de 2,6 ± 0,57. La durée moyenne d’opération était de 88 ± 27 minutes. Le diamètre moyen de toutes les lésions était de 4,8 ± 1,3 cm (entre 1,2 et 21 cm). La quantité moyenne de saignements rencontrés au cours des opérations était de 118 ± 23 ml. Des complications postopératoires ont été observées chez quatre patients (5,5%). La mortalité næa été observée chez aucun des patients. La durée moyenne dæhospitalisation était de 6,2 ± 2,1 jours. Le type histologique le plus courant était læadénome bénin (48,8%).

Conclusion:

Dans un pays en développement, læadrénalectomie ouverte est une alternative sûre à læadrénalectomie laparoscopique qui a une courbe dæapprentissage difficile.

INTRODUCTION

Wide use of imaging techniques results in more frequent diagnosis of adrenal lesions that require surgical intervention in cases with functional and malignancy. In a study which used higher resolution computed tomography (CT) scans, the incidental prevalence of adrenal incidentaloma was found %4, 4.[1] In autopsy studies, the prevalence of incidentalomas is 2%, and it ranges from 1 to 9.[2]

There are three milestones in the surgical treatment of adrenal disease in the last century. First, the structures of the adrenal steroids were gradually established during 1930 and 1940. The biochemical studies of the structure and synthesis of adrenocortical steroids by Reichenstein in Switzerland and Kendal and Hench in the USA resulted in the award of the Nobel Prize in physiology and medicine.[3] In addition to this knowledge, Rosalind Yalow discovered the radioimmunoassay and he was awarded the Nobel Prize in physiology and medicine in 1977.[4] This discovery resulted in easy and quick measurements of the hormones.[4].

The second milestone is the development of adrenal imaging. Cross-sectional imaging with CT was first used in 1975 and along with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) remains the mainstay of localization investigation today.[5,6] Moreover, the third milestone is the use of laparoscope for surgical removal of the adrenal gland by Gagner et al. 1992.[7]

In the past two decades, laparoscopic adrenalectomy (LA) was performed by many surgical clinics successfully.[8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] Except three clinics in the world, this operation was done in many series by a single experienced surgeon.[8,9,10] LA has a learning curve as the other laparoscopic procedures. The learning curve for LA is proposed to be between forty and fifty procedures.[8,9,15] The appropriate experience needs a long time in a developing country due to low volumes. On the other hand, in this study, we want to present our experience about open adrenalectomy with improved surgical care and instruments during laparoscopic era.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our hospital is the endocrine tertiary referral center for the northeast of Turkey. Patients are referred from the district general hospitals across the region to the endocrinology department of our hospital. Following comprehensive endocrinological investigations, the patients with adrenal mass are referred to our department for adrenalectomy.

A retrospective and descriptive study of patients with adrenal mass undergoing open adrenalectomy in the surgery department of our hospital between January 1993 and January 2013 was carried out. The local ethics committee confirmed that formal approval was not required for this retrospective audit study. All operations were performed by two surgeons.

The indications for the adrenal mass surgery were either for hormonally active neoplasm or malignant neoplasms or nonfunctioning neoplasm greater or equal to 4 cm with proven growth. Patients under the age of 18 years were excluded from the study.

All patients underwent preoperative imaging studies (ultrasound, CT, and MRI). Adrenal venous sampling was used in selected patients with Conn syndrome. 131I-Metaiodobenzylguanidine was used in some ectopic cases with pheochromocytoma.

Preoperative evaluation included a complete history and physical examination and measurements of serum electrolytes, creatinine, and a complete blood count. Those with suspected adrenal mass underwent a complete endocrine evaluation. For identifying possible functional tumors, we tested for 24-h urine metanephrine and catecholamine levels, plasma metanephrine levels, aldosterone level, plasma renin activity, cortisol level after low-dose suppression with 1 mg of dexamethasone. If the screening test is positive, confirmatory test was done such as adrenal vein catecholamines, clonidine suppression test, 24-h cortisol, high-dose dexamethasone suppression test, plasma corticotropin, metyrapone stimulation test, urinary aldosterone, aldosterone–renin ratio, postural stimulation test, and adrenal vein aldosterone.

In cases with pheochromocytoma, the medical management of pheochromocytoma at the preoperative phase is aimed mainly at blood pressure control and volume repletion. Alpha-blockers such as phenoxybenzamine are started 1–3 weeks before surgery at doses of 10 mg twice daily, which may be increased to 300–400 mg/d with rehydration. Beta-blockers such as propranolol at doses of 10–40 mg every 6–8 h often need to be added preoperatively in patients who have persistent tachycardia and arrhythmias. Patients also were given adequate volume repletion preoperatively to avoid postoperative hypotension, which ensues with the loss of vasoconstriction after tumor removal.

All patients underwent open anterior adrenalectomy under general anesthesia. To complete this retrospective audit, case notes were retrieved and reviewed. The following data were collected: demographics, indication for treatment, comorbidities, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, previous abdominal operation, operating time, blood loss, length of hospital stay, complications (using Clavien-Dindo classification), histological diagnosis, and size of specimen.[20]

Patients were followed in the first 6 months with a 3-month interval and later with a 6-month interval.

Data were analyzed using statistical package SPSS 13.01 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA, and serial number 9069728). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, tables, and figures. For group comparison, the Mann–Whitney U-test was used. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

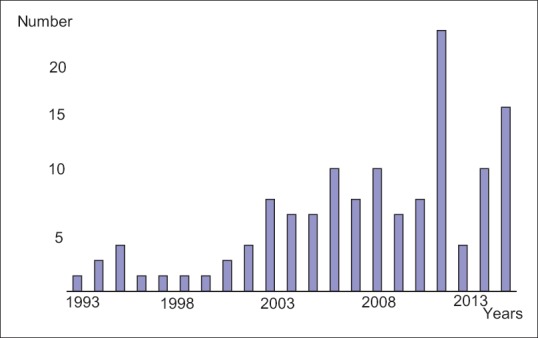

Between January 1993 and January 2013, ninety patients were operated in the surgery department of our hospital. The mean number of adrenal operations per month during this period was 0.38 ± 0.12 [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The distribution of the cases according to the years

The patient included 35 men (38.8%) and 55 women (61.2%), with a median age of 46.4 ± 17 years [Table 1]. The mean BMI was 28.4 ± 5.25, and the mean ASA score was 2.6 ± 0.57. Seven patients had previous abdominal surgery. The mean operative time was 88 ± 27 min. The right side mean operative time was 84 ± 22 min and left side was 94 ± 26 min. The mean maximum diameter of all the lesions estimated by ultrasound, CT, or MRI was 4.8 ± 1.3 cm (range: 1.2–21 cm). These values were 4.42 ± 1.8 cm in patients with pheochromocytoma and 9.6 ± 3.6 cm in patients with adrenocortical cancer. The mean blood loss was 118 ± 23 ml during the operations.

Table 1.

Demographic details, operative details and outcomes

| Parameters | |

|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 46.4±17 |

| Sex distribution | |

| Male | 35 (38.8%) |

| Female | 55 (61.2%) |

| BMI (kg/m2)a | 28.4±5.25 |

| ASA scorea | 2.6±0.57 |

| Side of resection | |

| Right | 40 (45%) |

| Left | 50 (55%) |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 7(7.7%) |

| Size of resected mass(mm)a | 4.8±1.3 |

| Operative time (min)a | 88±27 |

| Operative bleeding value(ml)a | 118±23 |

| Operative blood transfusion (number) | 2(2.2%) |

| Mortality (number) | 0 (%0) |

| Length of stay (days)a | 6.2±2.3 |

| 30 day re-operation rate | 0 |

| Surgical complicationsb | |

| Grade I | 1 (1.1%) |

| Grade II | 4 (4.4%) |

aValues are mean (±standard deviation). bSurgical complications are presented according to the classification system proposed by PA Clavien (20). BMI=Body mass index, ASA=American society of anaesthesiologists

Postoperative complications were observed in five patients (5.5%) (one retroperitoneal hematoma, three operative bleeding which needed blood transfusion, and one pneumonia). There was no mortality after the operations. The mean length of hospital stay was 6.2 ± 2.3 days.

Hormonal activity of the tumors in our study was observed as 29 (32.2%) aldosterone-secreting tumor, 18 (20%) catecholamine-secreting tumor, 10 (11.1%) glucocorticoid- secreting tumor, and 1 (1.1%) virilizing tumor [Table 2].

Table 2.

Hormonal activity of the tumors

| Nonfunctioning adrenal tumor | 32 (35.5%) |

| Catecholamine-secreting tumor | 18 (20 %) |

| Glucocorticosteroid-secreting tumor | 10 (11.1%) |

| Aldosterone-secreting tumor | 29 (32.2%) |

| Virilizing tumor | 1 (1.1%) |

Histological type of the tumor was given in Table 3. The most frequent type was benign adenoma and secondly aldosterone-secreting tumor. The mean operative time of the aldosterone-secreting tumor was 85 ± 21 min, and their mean blood loss was 112 ± 22 ml. There was no significant change between the cases of aldosterone-secreting tumor and the other cases. Adrenal venous sampling was used for the localization in 12 (41.9%) of those cases. These cases had no severe complications during the postoperative period.

Table 3.

Analysis of histological types of removed tumors

| Histological type of the tumor | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Adenoma | 44 (48.8) |

| Pheochromocytoma | 18 (20) |

| Nodular hyperplasia | 7 (7.7) |

| Myelolipoma | 6 (7.4) |

| Adrenocortical cancer | 4 (4.4) |

| Metastasis | 3 (3.3) |

| Pseudocystis | 3 (3.3) |

| Ganglioneuroma | 2 (2.2) |

| Pheocromocytoma+ Ganglioneuroma | 1 (1.1) |

| Oncocytic adenoma | 1 (1.1) |

| Corticomedullary mixt tumor | 1 (1.1) |

| Total | 90 (100) |

Pheochromocytoma was found in 18 cases of our series. There was no bilateralism and malignancy in our cases. The mean operative time of these cases was 102 ± 32 min, and the mean blood loss was 132 ± 32 ml. There were no significant differences between the cases of pheochromocytoma and the other cases. Metaiodobenzylguanidine was used in four pheochromocytoma cases. We observed hypertensive crises in three (16.6%) cases during the operation before the removal of the lesion. Postoperative course of those cases was uneventful.

Adrenocortical cancer was seen in four patients. One case is still alive without recurrence. One case with a 21-cm mass died at the 8th month. Two cases with recurrence are living under chemotherapy for 2 years.

The mean follow-up period was 7.8 ± 4.6 years (ranging from 16 months to 14 years). The follow-up rates were 96% after 1 year, 82% after 2 years, 48% after 5 years, and 28% after 10 years.

DISCUSSION

Adrenal disorder that required surgical correction is rare. Despite several reports of surgical removal of the pathologically enlarged adrenal glands, it is believed that no adrenal tumor was precisely diagnosed preoperatively before 1905.[21] Plain abdominal radiography, retroperitoneal gas insufflation, pyelography, caval venous sampling, selective adrenal venous sampling, and scintigraphy were used until 1975 for diagnostic localization of adrenal lesion.[5,6] After 1975 first CT, subsequently, ultrasonography and MRI were used for easy diagnosis of adrenal lesion.[5,6] On the other hand, wide use of imaging techniques due to other causes leads to more frequent diagnosis of the adrenal lesions.

Besides, more use of CT from other causes, the investigation of resistant hypertension increased the incidence of the adrenal lesions.[15] We observed two-third of our series as hormone-active adrenal lesions (Conn’s syndrome, pheochromocytoma, and cortisol-secreting tumor), and the most common lesion was Conn’s syndrome. These results are correlated with the literature with a proportion range of 21%–28%.[8,9,13,15] We found 32.2% of the cases as Conn’s syndrome in our study.

Knowley Thornton who has been considered as performing first successful adrenalectomy for suprarenal tumor, operated that case in London in 1889 and reported it in 1890.[22] Later, till 1950, many techniques such as anterior abdominal, flank, and open adrenalectomy (OA) techniques have been developed.[23] OA was unchallenged until 1992, when Gagner et al. described a transperitoneal laparoscopic approach to the gland.[12] This technique has been extensively accepted by endocrine surgical community and others described a posterior retroperitoneal laparoscopic approach.[11]

Today, LA has become the “gold standard” for the adrenal surgery. It reduces analgesic requirements, shorter length of hospital, and earlier returns to work, reduced morbidity, and reduced hospital cost.[8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] On the other hand, LA has a learning curve as other laparoscopic procedures.[10,15] The learning curve for LA is proposed to be 40–50 operations.[9,12,15] Except a few centers, LA has been performed by one or two experienced surgeons.[8,9] This theme is an important problem in developing countries with low-volume patients such as our country.

Our operations in this series were performed by two experienced surgeons. We observed in our study that the mean operative time was 88 ± 27 min, the mean maximum diameter of all the lesions was 4.8 ± 1.3 cm (range: 1.2–21 cm), and the mean blood loss was 118 ± 23 ml during the operations; there was no mortality after the operations, and the mean length of stay was 6.2 ± 2.3 days.

LA is a difficult surgical procedure that leads to complications during and after surgery with morbidity or even death. Gumbs and Gagner reported in large series with 2565 cases and found that the complication rate was 2.9%–15.5%.[7,8,9,10,24] Our complication rate was 5.5% after OA.

Pheochromocytoma is an endocrine rare tumor, most common in women in their 40s and 50s.[25,26] The “rule of 10” is used to describe pheochromocytoma; 1 of every 10 patients have malignant pheochrocytoma, 1 of every 10 patients has bilateral tumor, 1 of every 10 patients has extra-adrenal tumor and 1 of every 10 cases is familial.[25,26] Pheochromocytoma can be treated with open or laparoscopic surgery with lower mortality and morbidity.[25,26] However, there are more risks associated with surgical treatment of pheochromocytoma, either open or laparoscopic, in spite of lower mortality and lower complications – blood pressure changes, intraoperative blood loss, and adverse cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction, pulmonary edema, and stroke.[25,26]

We operated 18 cases of pheochromocytoma with 102 ± 32 min operative time and 132 ± 32 ml mean blood loss. Those values were insignificant with other cases in our study. We did not observe bilateral, malignant, or familial cases. The low number of our cases may explain our findings. “ In the literature, laparoscopically-operated pheochromocytoma cases have been reported with longer operation times and more postoperative bleeding.[16,25] Despite adequate volume resuscitation, the use of alpha- and beta-blocker and blood pressure changes occur during the operation till the removal of the lesion. We observed hypertensive crises in three (16.6%) cases during the operation before the removal of the lesion.

Adrenocortical carcinoma is a rare malignant disease with a poor diagnosis.[27] As there are a few adrenocortical cancer cases in our study, we do not have sufficient empirical evidence.

Our study has certain limitations due to retrospective single-center analysis, the difficulties of the collection, and the interpretation of the data of a 20-year period with shorter follow-up and biases inherent in any retrospective study. Furthermore, the sample size is still relatively small. Ideally, a randomized prospective trial should settle this important issue. However, we give a chance to literature to compare their LA results with our OA study.

CONCLUSION

Today, OA is a safe operative approach with advanced diagnostic and imaging methods, improved anesthesia, and postoperative care in developing countries. It will take time to change to LA instead of OA.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bovio S, Cataldi A, Reimondo G, Sperone P, Novello S, Berruti A, et al. Prevalence of adrenal incidentaloma in a contemporary computerized tomography series. J Endocrinol Invest. 2006;29:298–302. doi: 10.1007/BF03344099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terzolo M, Stigliano A, Chiodini I, Loli P, Furlani L, Arnaldi G, et al. AME position statement on adrenal incidentaloma. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164:851–70. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns CM. The history of cortisone discovery and development. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2016;42:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yalow RS. The Nobel lectures in immunology The Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine, 1977 awarded to Rosalyn S Yalow. Scand J Immunol. 1992;35:1–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1992.tb02828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheedy PF, 2nd, Stephens DH, Hattery RR, Muhm JR, Hartman GW. Computed tomography of the body: Initial clinical trial with the EMI prototype. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1976;127:23–51. doi: 10.2214/ajr.127.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sohaib SA, Peppercorn PD, Allan C, Monson JP, Grossman AB, Besser GM, et al. Primary hyperaldosteronism (Conn syndrome): MR imaging findings. Radiology. 2000;214:527–31. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.2.r00fe09527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gagner M, Lacroix A, Bolté E. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy in Cushing’s syndrome and pheochromocytoma. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1033. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210013271417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walz MK, Alesina PF, Wenger FA, Deligiannis A, Szuczik E, Petersenn S, et al. Posterior retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy results of 560 procedures in 520 patients. Surgery. 2006;140:943–8. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berber E, Tellioglu G, Harvey A, Mitchell J, Milas M, Siperstein A. Comparison of laparoscopic transabdominal lateral versus posterior retroperitoneal adrenalectomy. Surgery. 2009;146:621–5. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pędziwiatr M, Wierdak M, Ostachowski M, Natkaniec M, Białas M, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A, et al. Single center outcomes of laparoscopic transperitoneal lateral adrenalectomy lessons learned after 500 cases: A retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2015;20:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mercan S, Seven R, Ozarmagan S, Tezelman S. Endoscopic retroperitoneal adrenalectomy. Surgery. 1995;118:1071–5. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gagner M, Pomp A, Heniford BT, Pharand D, Lacroix A. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy: Lessons learned from 100 consecutive procedures. Ann Surg. 1997;226:238–46. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199709000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson GB, Grant CS, van Heerden JA, Schlinkert RT, Young WF, Jr, Farley DR, et al. Laparoscopic versus open posterior adrenalectomy: A case-control study of 100 patients. Surgery. 1997;122:1132–6. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(97)90218-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miccoli P, Raffaelli M, Berti P, Materazzi G, Massi M, Bernini G, et al. Adrenal surgery before and after the introduction of laparoscopic adrenalectomy. Br J Surg. 2002;89:779–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali JM, Liau SS, Gunning K, Jah A, Huguet EL, Praseedom RK, et al. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy: Auditing the 10 year experience of a single center. Surgeon. 2012;10:267–72. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conzo G, Musella M, Corcione F, De Palma M, Avenia N, Milone M, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of pheochromocytomas smaller or larger than 6 cm A clinical retrospective study on 44 patients Laparoscopic adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma. Ann Ital Chir. 2013;84:417–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lezoche G, Baldarelli M, Cappelletti Trombettoni MM, Polenta V, Ortenzi M, Tuttolomondo A, et al. Two decades of laparoscopic adrenalectomy: 326 procedures in a single-center experience. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2016;26:128–32. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cabalag MS, Mann GB, Gorelik A, Miller JA. Posterior retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy: Outcomes and lessons learned from initial 50 cases. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85:478–82. doi: 10.1111/ans.12508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Liu B, Wu Z, Yang Q, Chen W, Sheng H, et al. Comparison of single-surgeon series of transperitoneal laparoendoscopic single-site surgery and standard laparoscopic adrenalectomy. Urology. 2012;79:577–83. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, et al. The clavien-dindo classification of surgical complications: Five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187–96. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richards O. Growths of kidneys and adrenals. Guy Hosp Rep. 1905;59:17–32. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thornton JK. Abdominal nephrectomy for large sarcoma of the suprarenal capsule: Recovery. Trans Clin Soc Lond. 1890;23:150–3. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Priestley JT, Sprague RG, Walters W, Salassa RM. Subtotal adrenalectomy for Cushing’s syndrome: A preliminary report of 29 cases. Ann Surg. 1951;134:464–75. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195109000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gumbs AA, Gagner M. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;20:483–99. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalady MF, McKinlay R, Olson JA, Jr, Pinheiro J, Lagoo S, Park A, et al. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma A comparison to aldosteronoma and incidentaloma. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:621–5. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8827-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conzo G, Musella M, Corcione F, De Palma M, Ferraro F, Palazzo A, et al. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy, a safe procedure for pheochromocytoma. A retrospective review of clinical series. Int J Surg. 2013;11:152–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mihai R. Diagnosis, treatment and outcome of adrenocortical cancer. Br J Surg. 2015;102:291–306. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]