Abstract

Objective

To examine the association between expansion of the Medicaid program under the Affordable Care Act and changes in healthcare spending among low income adults during the first four years of the policy implementation (2014-17).

Design

Quasi-experimental difference-in-difference analysis to examine out-of-pocket spending and financial burden among low income adults after Medicaid expansions.

Setting

United States.

Participants

A nationally representative sample of individuals aged 19-64 years, with family incomes below 138% of the federal poverty level, from the 2010-17 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Main outcomes and measures

Four annual healthcare spending outcomes: out-of-pocket spending; premium contributions; out-of-pocket plus premium spending; and catastrophic financial burden (defined as out-of-pocket plus premium spending exceeding 40% of post-subsistence income). P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Results

37 819 adults were included in the study. Healthcare spending did not change in the first two years, but Medicaid expansions were associated with lower out-of-pocket spending (adjusted percentage change −28.0% (95% confidence interval −38.4% to −15.8%); adjusted absolute change −$122 (£93; €110); adjusted P<0.001), lower out-of-pocket plus premium spending (−29.0% (−40.5% to −15.3%); −$442; adjusted P<0.001), and lower probability of experiencing a catastrophic financial burden (adjusted percentage point change −4.7 (−7.9 to −1.4); adjusted P=0.01) in years three to four. No evidence was found to indicate that premium contributions changed after the Medicaid expansions.

Conclusion

Medicaid expansions under the Affordable Care Act were associated with lower out-of-pocket spending and a lower likelihood of catastrophic financial burden for low income adults in the third and fourth years of the act’s implementation. These findings suggest that the act has been successful nationally in improving financial risk protection against medical bills among low income adults.

Introduction

Affordability of healthcare has been a longstanding concern for many Americans,1 especially low income families. These families often have insufficient health insurance coverage or none at all, and therefore have to balance medical bills and basic living expenses, such as food, housing, and transportation.2 Uninsured individuals often postpone or forgo necessary healthcare services because of the cost, badly affecting their health.2 People who are uninsured are also at a higher risk of financial catastrophe due to unexpected medical bills.3 The Affordable Care Act (box 1)—signed into law by former President Barack Obama in 2010—was intended to alleviate the financial difficulties of obtaining adequate health insurance for the 50 million American people who were uninsured and a large number who were underinsured.2 4 A major component of the act was expanded eligibility for the Medicaid program (public health insurance for low income Americans) to people aged 19 to 64 with family incomes lower than 138% of the federal poverty level. Evidence indicates that states that have expanded Medicaid have successfully reduced the number of uninsured and underinsured low income individuals in comparison with states that have not expanded the program.5 6 7 8 9

Box 1. Key features of the Affordable Care Act.

The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was one of the most comprehensive reforms of the US healthcare system in recent history. The primary goal of the act was to reduce the number of uninsured and underinsured Americans, who accounted for 16% of the total population in 2010.

The Affordable Care Act has two major components. First, expansion of the eligibility criteria for Medicaid—public health insurance for low income individuals—up to 138% of the federal poverty level (“Medicaid expansion”); and, second, provision of health insurance marketplaces that allow individuals with 100-400% of the federal poverty level to purchase health insurance with subsidies.

Medicaid is structured as a federal state partnership; states administer Medicaid programs with substantial flexibility, although subject to federal standards. Before the act, individuals had to belong to a specific category (eg, children, pregnant women, people with disabilities) in order to be eligible for Medicaid coverage. The Affordable Care Act effectively eliminated these categories for eligibility and replaced them with uniform eligibility criteria—namely, below 138% of the federal poverty level ($17 236 (£13 193; €15 480) for a household of one in 2019) for states that expanded Medicaid programs. Although the Medicaid expansions were initially intended to be introduced nationally, a Supreme Court ruling in 2012 essentially made it optional for states.

Research has shown that the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions reduced the number of uninsured individuals from 16% to 8% of the population. Evidence is weak, however, as to how it affected the financial risk protection of low income individuals in the US.

Although reduction of the number of uninsured individuals is an important measure for assessing the effect of the Affordable Care Act, one of the primary goals of the act was to provide individuals with improved financial protection. Individuals who gain insurance could still face large amounts of out-of-pocket spending, which could lead to a catastrophic financial burden (medical expenses accounted for 37% of bankruptcies in the US in 2013-1610). Evidence is limited as to whether the Medicaid expansions have improved protection from financial risk. Studies are limited because they used data from a small number of states,11 12 13 relied on indirect measures of financial risk protection (eg, self-report of whether they were worried about the ability to pay medical bills),8 9 14 15 16 17 or did not compare states that had expanded Medicaid with those that had not.18 Therefore, whether the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions were associated nationally with improved financial risk protection among low income adults remains unclear.

In this study, we used a quasi-experimental difference-in-difference approach to examine whether states that expanded Medicaid in the context of the Affordable Care Act experienced reductions in out-of-pocket spending and catastrophic health expenditure during the first four years (from 2014 through 2017) of the Medicaid expansions. We used nationally representative data of a low income non-elderly population who were the target beneficiaries of the Medicaid expansion policy.

Methods

Data source and study population

We used the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, a nationally representative annual survey of the non-institutionalized civilian population in the US by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, from the years 2010 through 2017.19 The survey uses an overlapping panel design, where every year a new panel is enrolled and completes five rounds of interviews covering two full calendar years. Collected data include demographics, family income, health status, healthcare use (eg, office visits, hospitalizations), and out-of-pocket spending, including payments for those services not covered by insurance and cost sharing, such as deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey verifies self-reported spending information with providers, hospitals, and pharmacies.20 In addition, the survey collects annual premium contribution data for private health insurance based on self-reports at the first interview of the survey year.21 An annual file containing information relevant to events during that calendar year is then published. The response rates of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey varied between 48.3% and 61.3% in 2010-17.22

All rates and model estimates were weighted to be nationally representative and accounted for sample design and non-response to the survey. Because of the overlapping design, the same individual may appear in the data from two consecutive annual files. They are treated as two separate observations, and the problem of multiple measurements is appropriately accounted for by the stratum and primary sampling unit design variables.23

In our analyses, we included individuals aged 19-64 years, with family incomes below 138% of the federal poverty level, based on the eligibility criteria of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions. We excluded observations with missing covariates (n=743). Missing income and employment values were imputed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality using logical editing and weighted sequential hot deck procedures.24

Expansion status

“Expansion states” were defined as states that implemented the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion or an equivalent program on 1 January 2014. We excluded seven states that introduced Medicaid expansion after 1 January 2014, and before 31 December 2017 (Michigan, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Alaska, Montana, and Louisiana), based on previous research.17 Using this definition, 26 states (including the District of Columbia) were identified as expansion states, and 18 were considered “non-expansion states” (appendix section 1). We used restricted access state identifiers to classify expansion status, which can be analyzed only at census research data centers.

Health insurance coverage

We examined health insurance coverage (uninsured, Medicaid, or private health insurance) at the individual level to understand the association between the expanded Medicaid eligibility and a potential change in healthcare spending outcomes (appendix section 2).

Healthcare spending outcome measures

We used four annual healthcare spending outcomes: out-of-pocket spending; premium contributions; out-of-pocket plus premium spending; and catastrophic financial burden. Out-of-pocket spending included deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance paid by each individual. Premium contributions included premiums only for private health insurance because the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey does not collect premium information for non-private insurance. Premiums for Medicaid and Medicare (public health insurance for the elderly and disabled), however, are usually zero or minimal for low income beneficiaries (appendix section 3).

Catastrophic financial burden was defined as out-of-pocket plus premium spending exceeding 40% of post-subsistence income. We used the post-subsistence income to evaluate the financial burden of healthcare spending incurred by low income adults according to the Consumer Expenditure Survey, an approach used in previous studies.25 26 This expenditure survey is conducted by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, which collects information on the complete range of consumers’ expenditures.27 We subtracted mean food expenses available in the expenditure survey data from family incomes to calculate the post-subsistence income for each individual. We could not account for the number of household members in the estimation of mean food expenses because the survey does not provide these data according to household size. Our definition of catastrophic financial burden is endorsed by the World Health Organization,28 and has been used in previous literature.3 25 We assumed that post-subsistence income was $100 (£77; €90) a year for negative values and values less than $100 a year, an approach used by a previous study.29

Adjustment variables

We adjusted for the characteristics of the study participants: age (as a continuous variable), sex, race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other), educational attainment (less than high school, high school or some college, bachelor’s degree, or more than a bachelor’s degree), employment status, family size (as continuous), number of children (none, one, or more than one), and annual family income (as continuous). The number of children was defined as the number of individuals 18 years or younger in the family. Family incomes were not included as an adjustment variable for the analysis of catastrophic financial burden, because they are used to define this outcome variable. Additionally, we included state and year fixed effects in our model to account for state time invariant confounders (both measured and unmeasured) and the national secular trend.

Statistical analysis

We used a quasi-experimental difference-in-difference design to compare changes in outcomes between individuals in expansion versus non-expansion states before and after the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions. We analyzed changes for three separate periods: before the expansion period (2010-13), the implementation period of the Medicaid expansions (2014-15), and the long term follow-up period (2016-17). A similar approach has been used in previous research.30 31 We included two interaction terms between the expansion state indicator and each of the indicators of the implementation period (2014-15) and long term follow-up period (2016-17) in the multivariable regression models. The changes in outcomes attributable to the Medicaid expansions were represented by regression coefficients of the interaction terms. More details of the model specification are provided in the appendix section 4.

For continuous outcomes (that is, out-of-pocket spending, premium contributions, and out-of-pocket plus premium spending), we used multivariable generalized linear models with log-link and gamma distribution to account for the highly skewed distribution of the spending data (appendix figure A),32 and report difference-in-difference estimates in relative percentage changes. We also report difference-in-difference estimates in US dollars using average marginal effects by calculating the differences in predicted outcomes at each category level of the interaction terms for each observation and averaging over our national sample.33 For binary outcomes (health insurance coverage and catastrophic financial burden), we used multivariable linear probability models, which allow better interpretation of the coefficients of the interaction terms than logistic regression models.8 34 35 36 We formally tested the parallel trend assumption of the difference-in-difference model (appendix section 5).

All analyses accounted for the complex survey design of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey and used robust standard errors clustered at the state level to account for the potential correlation of observations within a state. We adjusted for P values using the Benjamini-Hochberg method to account for multiple comparisons—that is, having two measurements for each outcome (years 2014-15 and 2016-17).30 31 37 38 This method explicitly controls the error rate of test conclusions among significant results.38 All healthcare spending data were adjusted to 2017 US dollars using the consumer price index.39 Statistical analyses were conducted with Stata software version 16.0 (StataCorp, TX).

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted a series of sensitivity analyses. First, we analyzed the data using different model specifications: ordinary least squares regression models with log-transformed outcome variables for spending outcomes, and logistic regression models for catastrophic financial burden. Second, we used alternative sample definitions: excluding states that provided substantial insurance coverage for low income adults before 2014; excluding states that partially implemented Medicaid expansions in 2010 or 2011; including states that implemented Medicaid expansions after 1 January 2014 and before 31 December 2017; excluding Wisconsin, which began comprehensive coverage for low income adults on 1 January 2014 without adopting the Medicaid expansions; excluding non-US born participants; restricting analysis to individuals with family incomes lower than 100% of the federal poverty level; and excluding Medicare beneficiaries. In addition, as a falsification test, we analyzed individuals with family incomes greater than 400% of the federal poverty level (expecting no change in healthcare spending after the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions in this population). Appendix section 6 provides more details on the sensitivity analysis.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, or in developing plans for the design or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results.

Results

Our study included 37 819 individuals (flowchart shown in appendix figure B). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of individuals in the expansion and non-expansion states based on the pooled data from 2010 to 2013. We found statistically significant differences in demographic characteristics, including race/ethnicity, education attainment, employment status, and health insurance coverage, between the expansion and non-expansion states. We also found that the average out-of-pocket spending, premium contributions, and out-of-pocket plus premium spending at baseline were significantly lower in the expansion states than in the non-expansion states. Similarly, the probability of individuals experiencing a catastrophic financial burden among our study population at baseline was significantly lower in the expansion states than in the non-expansion states.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of individuals by Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion status*

| Characteristics | Expansion states (n=11 708) | Non-expansion states (n=8448) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age (years | 38.4 (15.7) | 38.0 (16.0) | 0.40 |

| Female (%) | 55.6 | 56.8 | 0.31 |

| Race/ethnicity (%): | 0.02 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 44.2 | 45.9 | |

| Hispanic | 29.2 | 25.4 | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 17.0 | 24.0 | |

| Other | 9.5 | 4.7 | |

| Education (%): | 0.03 | ||

| <High school | 29.1 | 27.8 | |

| High school or some college | 60.7 | 64.4 | |

| Bachelor's degree | 8.0 | 6.6 | |

| >Bachelor's degree | 2.1 | 1.3 | |

| Employed (%) | 43.6 | 46.8 | 0.04 |

| Married (%) | 31.1 | 33.6 | 0.22 |

| Mean (SD) family size | 2.8 (2.2) | 2.8 (2.2) | 0.82 |

| Number of children aged ≤18 (%): | 0.64 | ||

| 0 | 51.5 | 51.8 | |

| 1 | 16.6 | 17.5 | |

| 2 or more | 31.9 | 30.7 | |

| Mean family income ($) | 15256 | 15076 | 0.55 |

| Health insurance (%)†: | |||

| Private insurance (%) | 22.6 | 27.1 | 0.01 |

| Medicaid (%) | 42.7 | 25.1 | <0.001 |

| Uninsured (%) | 31.7 | 44.1 | <0.001 |

| Study outcomes ($): | |||

| Out-of-pocket spending‡ | 429 | 538 | 0.01 |

| Premium contributions§ | 688 | 827 | 0.09 |

| Out-of-pocket plus premium spending§ | 1418 | 1770 | 0.009 |

| Catastrophic financial burden¶ | 18.8 | 21.5 | 0.04 |

SD=standard deviation. $1=£0.77; €0.90.

Values are weighted to be nationally representative of individuals aged 19-64 years with family incomes lower than 138% of the federal poverty level based on the pooled data of Medical Expenditure Panel Survey 2010-13. US dollars are adjusted for inflation to 2017 using the consumer price index.

Definitions of health insurance variables shown in appendix section 2.

Out-of-pocket spending includes deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance paid by each individual.

Family level premium contributions were assigned to each individual in the family. Similarly, family level out-of-pocket plus premium spending were calculated by summing out-of-pocket spending paid by all family members and family level premium contributions, and then assigning the value to each member of the family.

Defined as annual out-of-pocket plus premium spending exceeding 40% of post-subsistence income.

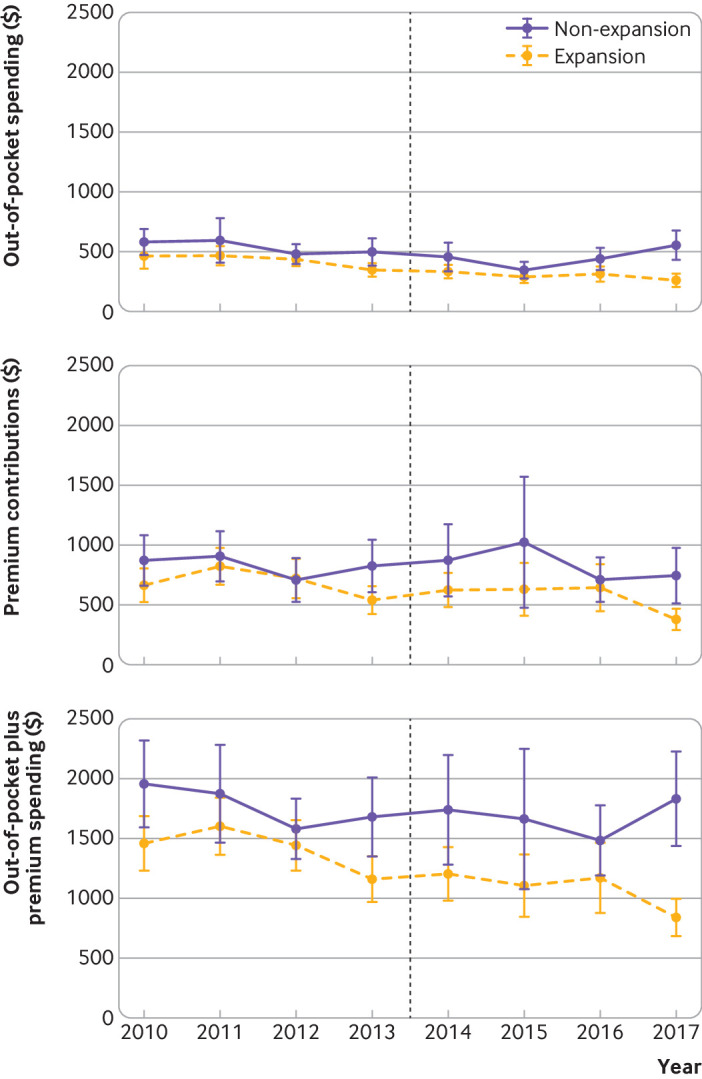

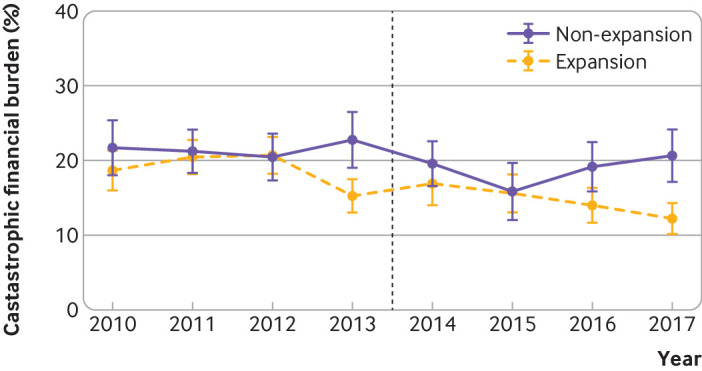

Figure 1 and figure 2 present unadjusted yearly trends in four outcomes for the expansion and non-expansion states. The formal tests showed no evidence that the baseline trends in outcome variables differ between expansion and non-expansion states. Appendix table A shows results of the tests for the parallel trend assumption.

Fig 1.

Unadjusted yearly trends in spending outcomes by Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion status. Data shown are weighted means of annual out-of-pocket spending, premium contributions, and out-of-pocket plus premium spending of individuals aged 19-64 with family incomes below 138% of the federal poverty level in states that expanded Medicaid on 1 January 2014, and non-expansion states, based on the 2010-17 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Spending values are converted to 2017 US dollars using the consumer price index. Black dashed line=implementation of the Medicaid expansion on 1 January 2014; bars=95% confidence intervals

Fig 2.

Unadjusted yearly trends in catastrophic financial burden by Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion status. Data shown are weighted prevalence of individuals living in families with catastrophic financial burden (out-of-pocket plus premium spending exceeding 40% of family post-subsistence income) among individuals aged 19-64 with family incomes below 138% of the federal poverty level in states that expanded Medicaid on January 1, 2014, and non-expansion states, based on the 2010-17 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Black dashed line=implementation of the Medicaid expansion on 1 January 2014; bars=95% confidence intervals

Our analysis of health insurance coverage found that the probability of being uninsured decreased, and the probability of being covered by Medicaid increased, in the expansion states relative to the non-expansion states after the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions, consistent with previous studies.8 9 We also found that the likelihood of being covered by private health insurance dropped after the Medicaid expansions, which is known as the “crowd-out”40 (appendix table B).

Healthcare spending outcomes

Although we found no evidence that out-of-pocket spending changed in 2014-15, it was lower in 2016-17 (adjusted percentage change −28.0% (95% confidence interval −38.4% to −15.8%); adjusted absolute change −$122; adjusted P<0.001; table 2). We found no evidence that premium contributions changed after implementation of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions. Although out-of-pocket plus premium spending change was not statistically significant in 2014-15, it was lower in 2016-17 (adjusted percentage change −29.0% (−40.5% to −15.3%); adjusted absolute change −$442; adjusted P<0.001). The probability of experiencing a catastrophic financial burden did not change in 2014-15, but was significantly lower in 2016-17 (adjusted percentage point change −4.7 (−7.9 to −1.4); adjusted P=0.01).

Table 2.

Change in spending outcomes and catastrophic financial burden after Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions*

| Outcome | Years 2014-15 (implementation period) | Years 2016-17 (long term follow-up period) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference-in-difference estimate (95% CI)† | P value | Difference-in-difference estimate (95% CI)† | P value | ||||||||

| Relative percentage change (%) |

Absolute change‡ |

Unadjusted | Adjusted § | Relative percentage change (%) |

Absolute change‡ |

Unadjusted | Adjusted § | ||||

| Out-of-pocket spending¶ | −19.1 (−34.6 to 0.0) | −$83 (−$158 to −$7) | 0.05 | 0.05 | −28.0 (−38.4 to −15.8) | −$122 (−$178 to −$67) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Premium contributions** | −14.3 (−37.8 to 17.9) |

−$114 (−$345 to $117) |

0.34 | 0.34 | −23.2 (−46.7 to 10.6) |

−$187 (−$425 to $52) |

0.16 | 0.31 | |||

| Out-of-pocket plus premium spending** | −15.0 (−29.3 to 2.2) |

−$225 (−$468 to $19) |

0.08 | 0.08 | −29.0 (−40.5 to −15.3) |

−$442 (−$650 to −$234) |

<0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Catastrophic financial burden, percentage points†† | 1.0 (−2.5 to 4.5) | 0.56 | 0.56 | −4.7 (−7.9 to −1.4) | 0.006 | 0.01 | |||||

1=£0.77; €0.90.

Values are weighted to be nationally representative of individuals aged 19-64 years with family incomes lower than 138% of the federal poverty level based on the pooled data of Medical Expenditure Panel Survey 2010-13. US dollars are adjusted for inflation to 2017 using the consumer price index.

Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, employment, marital status, family size, number of children, and family incomes (for spending outcomes only) as well as specific fixed effects for state and year.

Estimated using average marginal effects. See the main text for details.

Adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method.

Out-of-pocket spending includes deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance paid by each individual.

Family level premium contributions were assigned to each individual in the family. Similarly, family level out-of-pocket plus premium spending were calculated by summing out-of-pocket spending paid by all family members and family level premium contributions, and then assigning the value to each member of the family.

Defined as annual out-of-pocket plus premium spending exceeding 40% of post-subsistence income. Data are percentage point changes rather than relative/absolute changes.

Sensitivity analyses

Our findings were qualitatively unaffected when different model specifications or alternative sample definitions were used. The falsification test focusing on individuals with incomes greater than 400% of the federal poverty level showed no evidence that healthcare spending changed after the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions for this population (appendix tables C and D).

Discussion

Principal findings

Using a nationally representative sample of the low income non-elderly population in the US, we found that the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions were associated with lower out-of-pocket spending, lower out-of-pocket plus premium spending, and lower probability of experiencing a catastrophic financial burden at the national level in the third and fourth years of the implementation. We found no significant changes in the first two years of its implementation, and no evidence that premium contributions changed after the implementation of the Affordable Care Act. These findings should be reassuring for policy makers as they suggest that the act successfully achieved one of its primary goals—namely, improving national protection from financial risk against medical bills among low income adults.

Our four years of data indicate that not only were Medicaid expansions associated with a statistically significant improvement in financial risk protection, but also the magnitude of the effect was large and clinically meaningful. Given that our analyses included both adults who were affected by the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions and adults who were not (eg, adults who were already covered by Medicaid before the Act, did not take up Medicaid after the Medicaid expansions, and were covered by private insurance throughout the study period), the size of effects among adults who were newly covered by the Medicaid program should be larger than the estimated impact in our study. We found no evidence that premium contributions changed after the introduction of the Medicaid expansions, suggesting that the national reduction in healthcare spending was driven primarily by the previously uninsured population being newly covered by the Medicaid programs (and not by individuals previously covered by the private health insurance switching to Medicaid).

Our findings suggest that it took two years for out-of-pocket spending to decrease after the Medicaid expansions. This delay might reflect a gradual take-up of Medicaid programs in expansion states as it could take several years for beneficiaries, program administrators, and providers to learn and implement Medicaid expansions.8 41 Possibly, also, a reduction in out-of-pocket spending during the first two years might have been offset by a “pent-up demand” among newly insured individuals, who were foregoing or delaying care due to a lack of insurance before Medicaid expansions.8 11 42 43

Our sensitivity analysis, restricted to participants with family incomes lower than 100% of the federal poverty level, showed a larger reduction in healthcare spending after the Medicaid expansions than we estimated in our main analysis (analysis of individuals with income below 138% of the federal poverty level). This larger reduction might indicate that the benefit of Medicaid coverage on financial risk protection is larger for lower income families. Possibly, also, the effect size was smaller among individuals with income in the range 100-138% of the federal poverty level because those individuals in this range living in the non-expansion states had access to subsidized health insurance marketplace plans developed by the Affordable Care Act.44

Our estimates indicate that one in seven low income individuals could still have a catastrophic financial burden even in the expansion states after the implementation of Medicaid expansions (appendix table E), and there are several possible reasons for this. First, individuals eligible for Medicaid could have periods without health insurance owing to coverage transitions associated with changes in life circumstances, such as a job and income changes (“churning”).45 Second, although states generally charge no premiums and nominal cost sharing (eg, $4 per outpatient service) for Medicaid enrollees,46 the total spending of enrollees could still be financially catastrophic for individuals with very low income. Possibly, also, some states are charging higher premiums and cost sharing from Medicaid beneficiaries through waivers.47 Finally, those with a high deductible private health insurance plan could still have a catastrophic financial burden even with health insurance coverage when they receive expensive healthcare services.48

Comparison with other studies

Our study builds on previous studies that examined the effectiveness of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions on household spending on healthcare. Miller and Wherry analyzed a national survey and found that the Medicaid expansions were associated with a significant decrease in respondents reporting “yes” to questionnaires asking if they were “worried about the ability to pay medical bills in the event of an illness or bad accident and problems paying medical bills.”8 Sommers et al studied the impact of Medicaid expansions using the data from three states (Kentucky, Arkansas, and Texas) and reported that Medicaid expansions were associated with a reduction in annual out-of-pocket spending of $88.11 Other reports include studies recording reduced collection balances in expansion states using credit bureau data,15 17 showing a higher likelihood of experiencing zero out-of-pocket spending and zero premium expenditure in expansion states,16 and a study describing changes in out-of-pocket spending using a simple pre-post comparison design without a control.18 While informative, these studies were limited as they were restricted to a small number of states,11 12 13 relied on indirect measures of healthcare spending,8 9 14 15 16 17 or did not use a robust study design that evaluated the effect of the Affordable Care Act.18 To our knowledge, this is the first national study that has examined the impact of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions on out-of-pocket spending based on valid and reliable data using a robust quasi-experimental design.

Limitations of the study

Our study has some limitations. First, although we used a difference-in-difference method to account for unmeasured confounders, expansion and non-expansion states could differ in a way that was not captured by a quasi-experimental approach. For example, although the federal government provides finances to cover more than 90% of costs for newly eligible individuals, some states did not expand Medicaid owing to concerns about the long term financial sustainability of their Medicaid programs.49 We could not eliminate the possibility of biases due to an event (eg, budget constraint) occurring at the same time as the Medicaid expansions that affected expansion and non-expansion states differently. However, the parallel trends of outcome variables between expansion and non-expansion states before the Medicaid expansions observed in our data support the validity of our findings. Second, the confidence intervals of some of our estimates were relatively large. Therefore, although we were confident about the statistical significance, we could not make precise estimates of the effect size of the Affordable Care Act Medical expansions. Future studies with larger samples are warranted to make more precise estimations of the effect sizes. Finally, people who responded to the survey might have different characteristics than those who did not. For this to introduce a non-response bias in our estimates, however, systematic differences between respondents and non-respondents must also differ systematically between expansion and non-expansion states, which we think is unlikely.

Conclusion and policy implications

In summary, using a nationally representative sample of the low income, non-elderly population, we found lower out-of-pocket spending, lower out-of-pocket plus premium spending, and a lower likelihood of catastrophic financial burden in the third and fourth years after the implementation of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions. Our findings suggest that the Act is probably achieving a key goal—improved financial risk protection from healthcare spending among low income adults.

Our study has important policy implications. The constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act is once again being challenged in the courts by attorneys from 18 states, and its repeal or substantial modification continues to be discussed by policy makers. Our findings suggest that, if our findings were causal, as many as one million low income individuals could face catastrophic financial burden nationally, if the Medicaid expansions were to be repealed.

Finally, even though our results show significant reductions in out-of-pocket spending and financial risk due to Medicaid expansions, an estimated 9.3 million Americans who were eligible for Medicaid in 2017 were still not enrolled, including an estimated 2.5 million who lived in states that had not expanded their Medicaid programs.2 These findings suggest that substantial barriers to Medicaid enrolment might persist not only in non-expanded states, but also in expanded states. Understanding and eliminating barriers to enrolment is important for the long term success of the Affordable Care Act.

What is already known on this topic

Under the Affordable Care Act, the eligibility for Medicaid—public health insurance for low income Americans—was expanded to people earning up to 138% of the federal poverty level in the United States

Evidence to date shows that the introduction of the act led to a significant decline in the number of uninsured patients

It remains unclear whether the Medicaid expansions were associated with improved financial risk protection among low income adults nationally

What this study adds

Using the US nationally representative sample of low income, working age adult Americans, results indicated that the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions were associated with lower out-of-pocket spending and a lower likelihood of catastrophic financial burden in the third and fourth years of the implementation

These findings suggest that the act achieved one of its primary goals—namely, to reduce financial strain due to medical bills among low income adults at the national level

Acknowledgments

We thank Benjamin D Sommers and Thomas Rice for insightful feedback; Abdelmonem A Afifi for statistical advice; and Ray F Kuntz at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and John Sullivan at the California Census Research Data Center (CCRDC) for assistance in obtaining access to the data. The research in this paper was conducted at the CCRDC with administrative support from AHRQ. The results, conclusions, and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the position or policy of the AHRQ or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Service.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Appendix

Contributors: HG, GFK, and YT conceived and designed the study. All authors interpreted the data, critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript. HG performed the statistical analyses. HG and YT drafted the initial manuscript. YT supervised the study and HG is the guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This study received no support from any organization.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The University of California, Los Angeles institutional review board approved this study (IRB#17-001630). Patient consent was not required for the study.

Data sharing: No additional data are available.

The lead author (HG) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: The data used for this study are de-identified and, therefore, the findings cannot be shared with the study participants directly.

References

- 1.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. New Kaiser/New York Times survey finds one in five working-age Americans with health insurance report problems paying medical bills. 2016. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/press-release/new-kaisernew-york-times-survey-finds-one-in-five-working-age-americans-with-health-insurance-report-problems-paying-medical-bills/.

- 2.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. The uninsured: a primer - key facts about health insurance and the uninsured under the Affordable Care Act. 2019. http://www.kff.org/uninsured/report/the-uninsured-a-primer-key-facts-about-health-insurance-and-the-uninsured-under-the-affordable-care-act/.

- 3. Scott JW, Raykar NP, Rose JA, et al. Cured into destitution: catastrophic health expenditure risk among uninsured trauma patients in the United States. Ann Surg 2018;267:1093-9. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Health insurance coverage in America, 2010. 2012. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/report/health-insurance-coverage-in-america-2010/.

- 5.National Center for Health Statistics. Health insurance coverage: early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January – March 2017. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201708.pdf.

- 6. Kominski GF, Nonzee NJ, Sorensen A. The Affordable Care Act’s impacts on access to insurance and health care for low-income populations. Annu Rev Public Health 2017;38:489-505. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sommers BD, Gawande AA, Baicker K. Health insurance coverage and health - what the recent evidence tells us. N Engl J Med 2017;377:586-93. 10.1056/NEJMsb1706645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miller S, Wherry LR. Health and access to care during the first 2 years of the ACA Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med 2017;376:947-56. 10.1056/NEJMsa1612890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wherry LR, Miller S. Early coverage, access, utilization, and health effects associated with the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions: a quasi-experimental study. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:795-803. 10.7326/M15-2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Himmelstein DU, Lawless RM, Thorne D, Foohey P, Woolhandler S. Medical bankruptcy: still common despite the Affordable Care Act. Am J Public Health 2019;109:431-3. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sommers BD, Maylone B, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Three-year impacts of the Affordable Care Act: improved medical care and health among low-income adults. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36:1119-28. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, et al. Oregon Health Study Group The Oregon experiment--effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1713-22. 10.1056/NEJMsa1212321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sommers BD, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Changes in utilization and health among low-income adults after medicaid expansion or expanded private insurance. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1501-9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Winkelman TNA, Chang VW. Medicaid expansion, mental health, and access to care among childless adults with and without chronic conditions. J Gen Intern Med 2018;33:376-83. 10.1007/s11606-017-4217-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Caswell KJ, Waidmann TA. The Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions and personal finance. Med Care Res Rev 2017;76:538-71. 10.1177/1077558717725164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abramowitz J. The effect of ACA state Medicaid expansions on medical out-of-pocket expenditures. Med Care Res Rev 2018;77:19-33. 10.1177/1077558718768895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hu L, Kaestner R, Mazumder B, Miller S, Wong A. The effect of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions on financial wellbeing. J Public Econ 2018;163:99-112. 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goldman AL, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, Bor DH, McCormick D. Out-of-pocket spending and premium contributions after implementation of the affordable care act. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:347-55. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS HC-201: 2017 full year consolidated data file. 2019. https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h201/h201doc.shtml.

- 20.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical expenditure panel survey medical provider component (MEPS-MPC) methodology report 2016 data collection. 2018. https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/annual_contractor_report/mpc_ann_cntrct_methrpt.pdf.

- 21.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS HC-200: 2017 person round plan public use file. 2019. https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h200/h200doc.shtml.

- 22.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS-HC response rates by panel. 2018. https://meps.ahrq.gov/survey_comp/hc_response_rate.jsp.

- 23.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Standard errors for MEPS estimates. https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/survey_comp/clustering_faqs.jsp.

- 24.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS HC-192: 2016 full year consolidated data file. 2018. https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h192/h192doc.shtml.

- 25. Khera R, Valero-Elizondo J, Okunrintemi V, et al. Association of out-of-pocket annual health expenditures with financial hardship in low-income adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the United States. JAMA Cardiol 2018;3:729-38. 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Combined expenditure, share, and standard error tables. 2019. https://www.bls.gov/cex/2017/combined/income.pdf.

- 27.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer expenditures and income: overview. 2016. https://www.bls.gov/opub/hom/cex/home.htm.

- 28.World Health Organization. Distribution of health payments and catastrophic expenditures methodology. 2005. https://www.who.int/health_financing/documents/dp_e_05_2-distribution_of_health_payments.pdf.

- 29. Banthin JS, Bernard DM. Changes in financial burdens for health care: national estimates for the population younger than 65 years, 1996 to 2003. JAMA 2006;296:2712-9. 10.1001/jama.296.22.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sentilhes L, Winer N, Azria E, et al. Groupe de Recherche en Obstétrique et Gynécologie Tranexamic acid for the prevention of blood loss after vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med 2018;379:731-42. 10.1056/NEJMoa1800942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tarnow-Mordi W, Morris J, Kirby A, et al. Australian Placental Transfusion Study Collaborative Group Delayed versus immediate cord clamping in preterm infants. N Engl J Med 2017;377:2445-55. 10.1056/NEJMoa1711281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Buntin MB, Zaslavsky AM. Too much ado about two-part models and transformation? Comparing methods of modeling Medicare expenditures. J Health Econ 2004;23:525-42. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Williams R. Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. Stata J 2012;12:308-31 10.1177/1536867X1201200209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Greene W. Testing hypotheses about interaction terms in nonlinear models. Econ Lett 2010;107:291-6 10.1016/j.econlet.2010.02.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Karaca-Mandic P, Norton EC, Dowd B. Interaction terms in nonlinear models. Health Serv Res 2012;47:255-74. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01314.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Puhani P. The treatment effect, the cross difference, and the interaction term in nonlinear “difference-in-differences” models. Econ Lett 2012;1:85-7 10.1016/j.econlet.2011.11.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc 1995;57:289-300. 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Glickman ME, Rao SR, Schultz MR. False discovery rate control is a recommended alternative to Bonferroni-type adjustments in health studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:850-7. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Archived consumer price index detailed reports. 2017. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/tables/detailed-reports/home.htm.

- 40. Cutler DM, Gruber J. Does public insurance crowd out private insurance? Q J Econ 1996;111:391-430. 10.2307/2946683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sommers B, Kronick R, Finegold K, Po R, Schwartz K, Glied S. Understanding participation rates in Medicaid: implications for the Affordable Care Act. 2012. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/understanding-participation-rates-medicaid-implications-affordable-care-act.

- 42. Fertig AR, Carlin CS, Ode S, Long SK. Evidence of pent-up demand for care after Medicaid expansion. Med Care Res Rev 2018;75:516-24. 10.1177/1077558717697014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Simon K, Soni A, Cawley J. The impact of health insurance on preventive care and health behaviors: evidence from the first two years of the ACA Medicaid expansions. J Policy Anal Manage 2017;36:390-417. 10.1002/pam.21972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Blavin F, Karpman M, Kenney GM, Sommers BD. Medicaid versus marketplace coverage for near-poor adults: effects on out-of-pocket spending and coverage. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37:299-307. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sommers BD, Gourevitch R, Maylone B, Blendon RJ, Epstein AM. Insurance churning rates for low-income adults under health reform: lower than expected but still harmful for many. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:1816-24. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid and CHIP eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost sharing policies as of January 2017: findings from a 50-state survey. 2017. https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-enrollment-renewal-and-cost-sharing-policies-as-of-january-2017-premiums-and-cost-sharing/.

- 47.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid and CHIP eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost-sharing policies as of January 2016: findings from a 50-state survey. 2016. https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-enrollment-renewal-and-cost-sharing-policies-as-of-january-2016-premiums-and-cost-sharing/.

- 48.Collins SR, Bhupal HK, Doty MM. Health Insurance coverage eight years after the ACA. 2019. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2019/feb/health-insurance-coverage-eight-years-after-aca.

- 49.Advisory Board. Where the states stand on Medicaid expansion. 2019. https://www.advisory.com/daily-briefing/resources/primers/medicaidmap.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Appendix