Abstract

Objective

To study the impact of maternal smoking during pregnancy on fractures in offspring during different developmental stages of life.

Design

National register based birth cohort study with a sibling comparison design.

Setting

Sweden.

Participants

1 680 307 people born in Sweden between 1983 and 2000 to women who smoked (n=377 367, 22.5%) and did not smoke (n=1 302 940) in early pregnancy. Follow-up was until 31 December 2014.

Main outcome measure

Fractures by attained age up to 32 years.

Results

During a median follow-up of 21.1 years, 377 970 fractures were observed (the overall incidence rate for fracture standardised by calendar year of birth was 11.8 per 1000 person years). The association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and risk of fracture in offspring differed by attained age. Maternal smoking was associated with a higher rate of fractures in offspring before 1 year of age in the entire cohort (birth year standardised fracture rates in those exposed and unexposed to maternal smoking were 1.59 and 1.28 per 1000 person years, respectively). After adjustment for potential confounders the hazard ratio for maternal smoking compared with no smoking was 1.27 (95% confidence interval 1.12 to 1.45). This association followed a dose dependent pattern (compared with no smoking, hazard ratios for 1-9 cigarettes/day and ≥10 cigarettes/day were 1.20 (95% confidence interval 1.03 to 1.39) and 1.41 (1.18 to 1.69), respectively) and persisted in within-sibship comparisons although with wider confidence intervals (compared with no smoking, 1.58 (1.01 to 2.46)). Maternal smoking during pregnancy was also associated with an increased fracture incidence in offspring from age 5 to 32 years in whole cohort analyses, but these associations did not follow a dose dependent gradient. In within-sibship analyses, which controls for confounding by measured and unmeasured shared familial factors, corresponding point estimates were all close to null. Maternal smoking was not associated with risk of fracture in offspring between the ages of 1 and 5 years in any of the models.

Conclusion

Prenatal exposure to maternal smoking is associated with an increased rate of fracture during the first year of life but does not seem to have a long lasting biological influence on fractures later in childhood and up to early adulthood.

Introduction

Maternal smoking during pregnancy is causally associated with fetal growth restriction and has consistently been associated with lower birth weight by about 150-200 g.1 2 3 Along with an overall reduction in birth weight, fetal skeletal growth seems to be particularly susceptible to the effects of maternal smoking.3 4 5 It has been hypothesised that smoking during pregnancy compromises accrual of fetal bone mass by decreasing intestinal calcium absorption and the supply of oxygen and nutrients to the developing fetus.6 7 In addition, constituents of tobacco smoke such as cadmium might exert direct toxic effects.8 9 Studies reporting inverse associations of birth weight with various indicators of bone health in adults10 11 suggest that maternal smoking might have a long lasting influence on skeletal development in offspring, possibly through intrauterine programming of the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor-1 axis.12 13 Mothers who smoke during pregnancy could thus predispose their offspring to a raised lifetime risk of impaired bone health.

Results from studies investigating associations of maternal smoking during pregnancy with bone health among offspring have been inconclusive. Two studies from the Southampton Women’s Survey cohort found a link between maternal smoking and a reduction in bone mass in neonates,14 15 but associations with bone mass during childhood and early adulthood have been mixed, with inverse,16 17 positive,18 19 or null associations.20 21 22 These inconsistent results could in part be because prenatal smoking exposure only has a transient effect on bone development or due to methodological heterogeneity across studies and variation in adjustment for confounding factors.

Smoking is an exposure strongly patterned by socioeconomic and lifestyle factors that pass from generation to generation, and associations with smoking during pregnancy are subject to residual confounding by unmeasured shared familial characteristics when using conventional observational analysis methods.23 Two studies found associations of similar magnitude for paternal and maternal smoking during pregnancy with bone mass in childhood (measured at ages 6 and 10 years) and concluded that associations with smoking in mothers during pregnancy are likely to be confounded by shared familial factors.18 19 This reasoning is based on the assumption that confounding factors would relate similarly to smoking in mothers and fathers but that smoking in fathers would be expected to have no, or a much weaker, intrauterine effect than smoking in mothers.24 These studies, however, only explored associations with bone mass, and other aspects of bone architecture might also be important for bone health in childhood. We are aware of only two studies25 26 that have looked at the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and fractures in offspring. These studies found an increased fracture incidence during the first year of life26 and at preschool age25 in offspring exposed to intrauterine smoking, but they could not explore potential confounding by shared familial characteristics. Furthermore, residual confounding by familial factors might vary across the life course, and this has not been addressed by previous studies that focused primarily on (early) bone mass or fractures in childhood. Thus the impact of maternal smoking during pregnancy on the bone health of offspring during different developmental stages of life remains uncertain.

We determined the association of maternal smoking during pregnancy with fracture risk in offspring from infancy to young adulthood. To strengthen causal inference, we compared siblings discordant for maternal smoking to account for unobserved confounding by familial (genetic or environmental) factors shared by siblings.27

Methods

Study population

We analysed data from a cohort of 1 680 307 liveborn singletons in Sweden, born between 1 January 1983 and 31 December 2000, with complete data on maternal smoking during pregnancy (see supplementary fig 1) and with maximum follow-up until 31 December 2014. This cohort was created by merging data from multiple Swedish registers (Medical Birth Register,28 Multi-Generation Register,29 Total Population Register,30 Cause of Death Register,31 National Patient Register,32 and LISA (the Swedish acronym for the Longitudinal Integration Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies).33 Individual record linkage was possible using the unique personal identification number assigned to all residents in Sweden and which are included in all registers. We carried out sibling comparison analyses in a subcohort comprising 1 234 992 siblings (including 1 142 936 full siblings) born to 531 884 mothers identified through the Multi-Generation Register (see supplementary methods).

Maternal smoking during pregnancy

Information on smoking in early pregnancy has been routinely collected in the Medical Birth Register since 1983. Information on cigarette smoking is based on questions asked by the midwife at the first antenatal visit, mostly during the first trimester at 8-12 weeks’ gestation, and is recorded as a categorical variable (non-smoker, 1-9 cigarettes/day, and ≥10 cigarettes/day). Studies have shown that this self-reported measure of smoking during pregnancy correlates well with maternal cotinine levels (κ=0.82), with only 5% of self-reported non-smokers classified as smokers using cotinine measurement.34 35

Outcome

Fractures were defined using diagnoses recorded in the Medical Birth Register (fractures in infants only) and the National Patient Register (fractures at any age) according to ICD-8, ICD-9, and ICD-10 codes (international classification of diseases, 8th, 9th, and 10th revisions, respectively): ICD-8 and 9 codes 800-829 and ICD-10 codes S02, S12, S22, S32, S42, S52, S62, S72, S82, S92, T02, T08, T10, T12 (see supplementary table 1). This definition cannot differentiate delivery related fractures from fractures related to other causes. For descriptive purposes we grouped fractures by anatomical site (skull and facial, neck and trunk, upper extremity, lower extremity, and other) and mechanism of injury (non-intentional trauma; assault, including abuse; other or unknown mechanisms) using ICD codes and diagnostic codes for external causes in the National Patient Register (see supplementary table 2). Among 2253 fractures diagnosed in infants before 1 year of age, 252 were recorded in the Medical Birth Register, and of these, 213 were only recorded in the Medical Birth Register (that is, 39 also had a fracture diagnosis in the National Patient Register).

Other variables

For each offspring, we obtained information on year of birth, sex, gestational age, and birth weight from the Medical Birth Register. Maternal characteristics for each index pregnancy (maternal age at birth, parity, height and body mass index (BMI) at the first antenatal visit) were also extracted from this register. Parental marital status and socioeconomic measures (highest completed education level from the Education Register and occupational classification defined using an approximation of the European Socio-economic Classification (ESeC)36) around the birth of each offspring was derived from LISA. See the supplementary methods for details on how these variables were included in the analytical models.

Statistical analysis

Distributions of parental and offspring characteristics were compared between mothers who smoked and those who did not smoke in early pregnancy. Follow-up time in our study was defined from birth until the date of first fracture diagnosis, emigration, death, or end of follow-up (31 December 2014), whichever occurred first. To examine the association of maternal smoking with risk of fracture in offspring, we first calculated standardised incidence rates (per 1000 person years) of fractures in exposed and unexposed offspring across different ages at follow-up (one year intervals). Incidence rates were standardised by calendar year of birth to account for birth cohort effects in smoking prevalence and fracture incidence. Cox regression analysis with attained age as the underlying time scale was used to assess the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and risk of fracture in offspring in whole cohort and within-sibship analyses. Because there was evidence of non-proportional hazards, we split person time by attained age such that associations were allowed to vary over time. Age groups were set using cut-off points that captured potentially relevant developmental periods: 0 to <1 year (infancy), 1 to <5 years (early childhood), 5 to <15 years (mid to late childhood and early adolescence), and ≥15 years (later adolescence and early adulthood).

Maternal smoking was defined as maternal smoking in early pregnancy, and modelled as dichotomous (no daily smoking, daily smoking) or as categorical ordinal variable (no daily smoking, 1-9 cigarettes/day, ≥10 cigarettes/day), and we assessed dose dependent associations using statistical tests for trend. Three models were fitted for these exposures: 1) a model adjusted for birth year only; 2) a model adjusted for all observed potential confounders—birth year, maternal age, parity, height, BMI, parental education, occupation, marital status, and sex of offspring (the last could not be a confounder but is related to outcome, and adjusting for this might improve statistical efficiency); and 3) a within-sibship analysis. We used stratified Cox regression models with fixed effects in a multilevel framework (siblings within families) to obtain within-sibship estimates. These models with a separate stratum for each family include all offspring with siblings, but only families who are discordant on both the exposure and the outcome are informative for the estimation of hazard ratios for fractures associated with maternal smoking. We compared within-sibship estimates obtained from these models with estimates in the whole cohort (model 2) to explore the extent to which associations with maternal smoking were driven by unmeasured familial confounding. The within-sibship analyses were adjusted for the same covariates as the multivariable analysis in the whole cohort but excluding maternal height, a variable that is unlikely to vary among siblings in the same family. By design, the within-sibship analysis only includes offspring with siblings. To evaluate the generalisability of the within-sibship results, we repeated the conventional multivariable analysis (model 2) in offspring with siblings (n=1 234 922) and those without siblings (n=445 385). Sandwich estimator corrected standard errors were used to account for familial clustering in the analysis including offspring with siblings.

To assess whether associations between maternal smoking and fracture risks in offspring were explained by small size at birth, we repeated analyses with additional adjustments for gestational age at birth and birth weight for gestational age. Potential effect modification by sex of offspring was also explored for all associations assessed. We further examined associations with repeated fracture risk using negative binomial regression models. This analysis focused on the number of fractures experienced by offspring during the entire period of follow-up and was adjusted for the same covariates as the analysis for occurrence of a first fracture. A fixed effects negative binomial model with a separate stratum for each family was used to examine within-sibship associations for repeated fracture risk.

We conducted several sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our findings. Firstly, we repeated the within-sibship analysis including full siblings only (n=1 142 936). Secondly, we evaluated the extent to which associations were influenced by the decreasing prevalence of smoking during pregnancy and changing diagnostic criteria over time by stratifying analyses by calendar period of birth (1983-91 and 1992-2000). Lastly, we explored the potential impact of missing covariate data by repeating analyses after multiple imputation of missing covariate data (see supplementary methods for details).

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata MP version 15 (StataCorp, TX).

Patient and public involvement

This is a general population study and not a study solely of patients. No participants were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for design or implementation of the study. No participants were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics of the offspring and their parents, overall and stratified by maternal smoking during pregnancy. Compared with mothers who did not smoke, those who smoked were younger, of shorter stature, more likely to be multiparous, more likely to be underweight or overweight in early pregnancy, and less likely to be married. Mothers who smoked during pregnancy also had lower level educational attainment, were more likely to have routine or manual occupations, and to have partners with lower education and routine or manual occupations. Infants of mothers who smoked during pregnancy had a lower gestational age and weight at birth.

Table 1.

Parental and infant characteristics by maternal smoking during pregnancy. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | All (n=16 80 307) | Maternal smoking during pregnancy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n=13 02 940) | Yes (n=377 367) | ||

| Parental characteristics | |||

| Maternal age (years): | |||

| <20 | 43 776 (2.6) | 25 552 (2.0) | 18 224 (4.8) |

| 20-24 | 350 843 (20.9) | 250 254 (19.2) | 100 589 (26.7) |

| 25-29 | 621 975 (37.0) | 493 401 (37.9) | 128 574 (34.1) |

| 30-34 | 454 709 (27.1) | 367 170 (28.2) | 87 539 (23.2) |

| ≥35 | 209 004 (12.4) | 166 563 (12.8) | 42 441 (11.2) |

| Maternal height (cm): | |||

| <155 | 42 022 (3.0) | 33 239 (3.0) | 8783 (2.9) |

| 155-164 | 511 968 (36.5) | 393 284 (35.9) | 118 684 (38.6) |

| 165-174 | 733 366 (52.2) | 575 759 (52.5) | 157 607 (51.2) |

| ≥175 | 116 506 (8.3) | 93 829 (8.6) | 22 677 (7.4) |

| Missing | 276 445 (16.5) | 206 829 (15.9) | 69 616 (18.4) |

| Maternal body mass index (kg/m2): | |||

| <18.5 | 58 540 (5.0) | 40 146 (4.4) | 18 394 (7.3) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 827 417 (71.0) | 654 244 (71.6) | 173 173 (68.9) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 213 032 (18.3) | 168 417 (18.4) | 44 615 (17.8) |

| ≥30.0 | 65 680 (5.6) | 50 616 (5.5) | 15 064 (6.0) |

| Missing | 515 638 (30.7) | 389 517 (29.9) | 126 121 (33.4) |

| Maternal parity: | |||

| Nulliparous | 693 810 (41.3) | 539 717 (41.4) | 154 093 (40.8) |

| 1 | 607 805 (36.2) | 480 972 (36.9) | 126 833 (33.6) |

| 2 | 265 846 (15.8) | 201 569 (15.5) | 64 277 (17.0) |

| ≥3 | 112 846 (6.7) | 80 682 (6.2) | 32 164 (8.5) |

| Maternal education: | |||

| Compulsory up to 9 years | 287 413 (17.6) | 166 743 (13.1) | 120 670 (32.7) |

| Secondary | 893 398 (54.6) | 684 956 (54.0) | 208 442 (56.5) |

| Post-secondary | 456 668 (27.9) | 417 115 (32.9) | 39 553 (10.7) |

| Missing | 42 828 (2.5) | 34 126 (2.6) | 8702 (2.3) |

| Maternal occupational classification*: | |||

| Low | 971 155 (57.8) | 704 671 (54.1) | 266 484 (70.6) |

| Intermediate | 328 018 (19.5) | 270 283 (20.7) | 57 735 (15.3) |

| High | 311 077 (18.5) | 278 412 (21.4) | 32 665 (8.7) |

| Missing | 70 057 (4.2) | 49 574 (3.8) | 20 483 (5.4) |

| Maternal marital status: | |||

| Not married | 651 902 (39.3) | 474 840 (36.9) | 177 062 (47.5) |

| Married | 937 856 (56.6) | 768 373 (59.8) | 169 483 (45.4) |

| Divorced or widowed | 68 618 (4.1) | 42 081 (3.3) | 26 537 (7.1) |

| Missing | 21 931 (1.3) | 17 646 (1.4) | 4285 (1.1) |

| Paternal education: | |||

| Compulsory up to 9 years | 336 267 (20.7) | 223 267 (17.7) | 113 000 (31.4) |

| Secondary | 852 749 (52.5) | 649 389 (51.4) | 203 360 (56.4) |

| Post-secondary | 434 226 (26.8) | 390 306 (30.9) | 43 920 (12.2) |

| Missing | 57 065 (3.4) | 39 978 (3.1) | 17 087 (4.5) |

| Paternal occupational classification: | |||

| Low | 1 037 614 (61.8) | 762 732 (58.5) | 274 882 (72.8) |

| Intermediate | 203 004 (12.1) | 168 129 (12.9) | 34 875 (9.2) |

| High | 373 226 (22.2) | 328 080 (25.2) | 45 146 (12.0) |

| Missing | 66 463 (4.0) | 43 999 (3.4) | 22 464 (6.0) |

| Infant characteristics | |||

| Sex: | |||

| Boy | 863 638 (51.4) | 669 223 (51.4) | 194 415 (51.5) |

| Girl | 816 669 (48.6) | 633 717 (48.6) | 182 952 (48.5) |

| Mean (SD) birth weight (g) | 3538 (556) | 3582 (548) | 3384 (559) |

| Missing | 0.4 (5899) | 0.3 (4490) | 0.4 (1409) |

| Mean (SD) gestational age at birth (weeks) | 39.4 (1.8) | 39.4 (1.8) | 39.2 (1.9) |

| Missing | 0.1 (996) | 0.0 (633) | 0.1 (363) |

| Small for gestational age (<10th centile): | |||

| No | 1 509 017 (90.2) | 1 192 715 (91.9) | 316 302 (84.2) |

| Yes | 164 425 (9.8) | 105 124 (8.1) | 59 301 (15.8) |

| Missing | 6865 (0.4) | 5101 (0.4) | 1764 (0.5) |

For all variables, numbers (percentages) are only given for singleton births with no missing values to facilitate comparison by maternal smoking during pregnancy.

Defined using an approximation of the European Socio-economic Classification (ESeC) and grouped into lower, intermediate, and higher level professions.36

The offspring were followed from birth to a median age of 21.1 years (maximum age 32 years), and during this period 377 970 fractures were observed. Supplementary table 3 presents descriptive details of fracture type by site and mechanism of injury. Most fractures had an accidental external cause. Before the age of 1 year, a relatively large proportion of skull or facial and femur fractures occurred. After 1 year of age, the distribution of fractures by site did not vary notably by attained age, and upper extremity fractures were most common. The distribution of fracture type was similar in offspring with and without siblings.

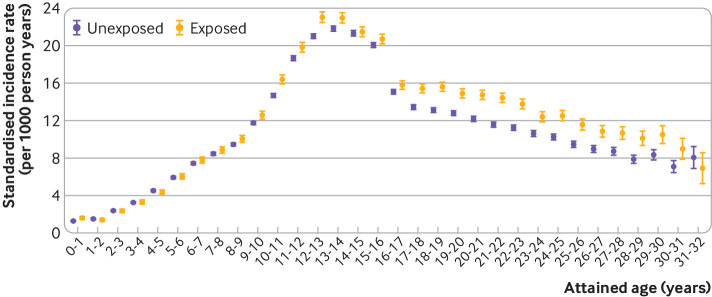

Overall, the birth year standardised fracture rate was 11.8 per 1000 person years. Figure 1 shows the birth year standardised incidence rates of fractures by attained age, stratified by maternal smoking during pregnancy (see supplementary table 4). The highest fracture rate was found around the ages when puberty typically occurs. Compared with non-exposed offspring, those prenatally exposed to maternal smoking tended to have higher fracture rates before 1 year of age and from the age of 6 years and onward. Before 1 year of age, the birth year standardised rates of fractures in those exposed and unexposed to maternal smoking were 1.59 and 1.28 per 1000 person years, respectively. The fracture rate during the first year of life was somewhat lower when only fractures recorded in the Patient Register were included, but this did not affect the relative difference in fracture risk by maternal smoking (see supplementary table 5). Stratified analyses by sex of offspring revealed that age related patterns of fractures rates by maternal smoking were similar in boys and girls (see supplementary figure 2 and table 6). However, overall, fracture incidence at any age was higher in boys than in girls, and the peak age of fracture occurrence was later in boys (see supplementary figure 2).

Fig 1.

Standardised incidence rates of fractures by attained age in offspring exposed and unexposed to maternal smoking during pregnancy. Incidence rates (per 1000 person years) are standardised by calendar year of birth and stratified by attained age. Incidence rates (95% confidence intervals) of fractures in offspring are for those whose mothers did and did not smoke during pregnancy

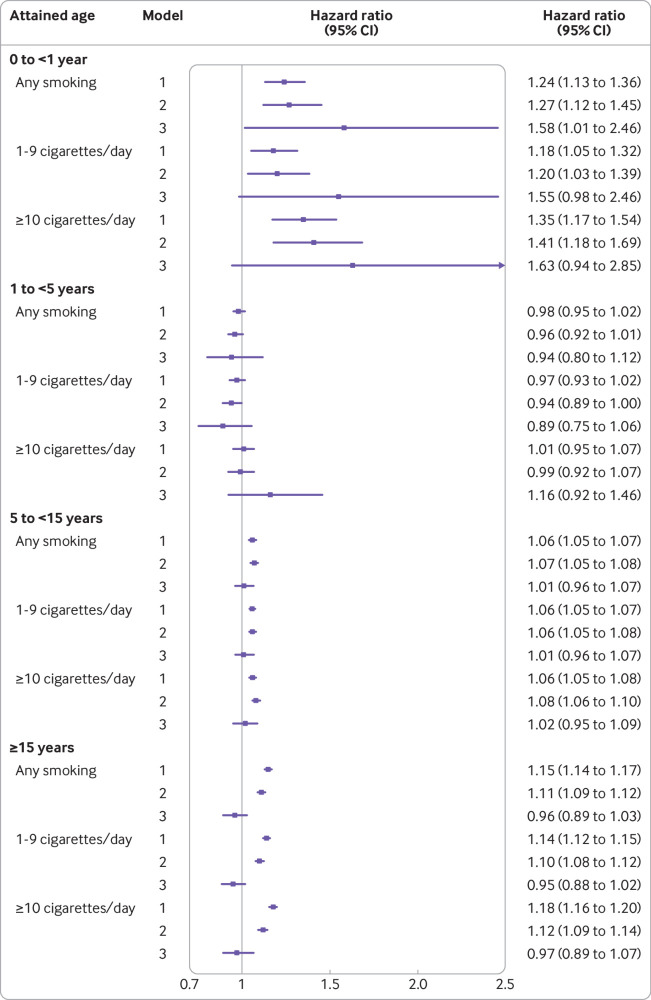

Figure 2 and supplementary table 7 summarise the results from whole cohort and within-sibship analyses. Maternal smoking during pregnancy was associated with fractures in offspring before 1 year of age in the entire cohort after adjustment for potential confounding factors (compared with no smoking, the adjusted hazard ratio for smoking was 1.27 (95% confidence interval 1.12 to 1.45)) with this association following a dose dependent pattern (compared with no smoking, adjusted hazard ratios for 1-9 cigarettes/day and ≥10 cigarettes/day were 1.20 (1.03 to 1.39) and 1.41 (1.18 to 1.69), respectively, P<0.001 for trend). The association with fractures during the first year of life persisted after additional adjustment for unmeasured shared familial factors through comparison of siblings discordant for exposure in within sibship analyses, although with wider confidence intervals (compared with no smoking, the hazard ratio for smoking was 1.58 (1.01 to 2.46)). Maternal smoking during pregnancy was also associated with fractures occurring from age 5 years and older in whole cohort analyses with multivariable adjustment (compared with no smoking, adjusted hazard ratios for smoking at 5 to <15 years and ≥15 years were 1.07 (1.05 to 1.08) and 1.11 (1.09 to 1.12), respectively). These associations, however, did not follow a clear dose dependent gradient and were attenuated to the null in within-sibship analyses. Maternal smoking was not associated with fractures between ages 1 and 5 years in any models.

Fig 2.

Maternal smoking during pregnancy and risk of fractures in offspring by attained age. Hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for fractures comparing offspring exposed to maternal smoking during pregnancy (any, 1-9 cigarettes/day, ≥10 cigarettes/day) with those unexposed (reference group). Hazard ratios are presented by attained age (0 to <1 year, 1 to <5 years, 5 to <15 years, ≥15 years) and for the different analysis models: model 1: whole cohort analysis adjusted for birth year; model 2: whole cohort analysis adjusted for birth year, sex of offspring, maternal age, parity, height, body mass index, parental education, occupation, and marital status; and model 3: within-sibship analysis including all covariates included in model 2 except for maternal height, a variable which is unlikely to vary among siblings in the same family

To further explore the association with early life fractures by age, we analysed associations with fractures diagnosed during the first three months of life and those from 3 months to 1 year of age. In whole cohort analyses, the results were essentially similar, while within-sibship analyses identified associations between maternal smoking and risk of fracture that appeared to be of higher magnitude closer to birth. However, these analyses were limited by lower statistical power (see supplementary table 8).

To evaluate the degree to which associations of maternal smoking with risk of fracture among offspring were explained by gestational age and birth weight for gestational age, analyses were repeated with additional adjustment for these variables. Overall, effect estimates were consistent with those observed in the main analysis (see supplementary table 9 for fractures before 1 year of age; the adjusted hazard ratios in whole cohort and within-sibship analyses were 1.27 (1.11 to 1.44) and 1.58 (1.01 to 2.48), respectively). Stratified analyses by offspring sex showed no clear evidence of differences in associations between girls and boys (see supplementary tables 10 and 11). Although tests for interaction were statistically significant during some periods of attained age in whole cohort analyses, all effect estimates were largely similar in male and female offspring.

Results for repeated fracture risk were largely consistent with those observed for first occurrence of fracture. Incidence rate ratios for recurrent fractures comparing offspring exposed and unexposed to maternal smoking indicated an association in whole cohort analyses, but there was no evidence of a dose dependent or within-sibship association between maternal smoking and repeated risk of fracture (see supplementary table 12).

Supplementary table 13 summarises parental and infant characteristics of offspring with and without siblings in the study population. On average, those without siblings had mothers who were slightly older, were slightly more highly educated, and had a somewhat higher socioeconomic position. These offspring were also more likely to be born small for gestational age. Overall, effect estimates from conventional multivariable adjusted analyses were not very different in offspring with and without siblings, supporting the generalisability of the within-sibship results (see supplementary table 14).

Sensitivity analyses, only including full-siblings, yielded similar estimates to those observed in analyses including all siblings (see supplementary table 15). Also, no strong evidence was found for a birth cohort effect, although associations with fractures in young adulthood appeared to be of higher magnitude among individuals born between 1983 and 1991 than in those born between 1992 and 2000 in whole cohort analyses, but not in within-sibship analyses (see supplementary tables 16 and 17). Results from sensitivity analyses with multiple imputation of missing covariate data did not differ noticeably from those based on complete case data, except for confidence intervals being narrower (see supplementary table 18).

Discussion

In this study, we found that maternal smoking during pregnancy was associated with an increased incidence of fractures among offspring during their first year of life, with consistency in this finding between whole cohort analyses and a within-sibship approach, and with additional evidence of a dose dependent relation. The positive association between maternal smoking and fracture risk in offspring from 5 to 32 years of age observed in whole cohort analyses with multivariable adjustment did not display a dose dependent pattern and did not persist in within-sibship analyses. These results suggest that maternal smoking in pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of fracture in offspring during their first year of life, whereas associations between maternal smoking and fracture risk later in childhood up to early adulthood are likely being driven by confounding by shared familial characteristics.

Strengths and limitations of this study

We examined the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and fractures in offspring from birth to early adulthood also using a sibling comparison design to deal with confounding by unmeasured familial (genetic or environmental) factors shared by siblings. The validity of fracture diagnoses recorded by the Patient Register is high.32 Other strengths are the size of this study, the prospectively recorded data, the range of covariates available, and the possibility to address risk of fractures during different developmental stages of life, as well as repeated risk of fracture. The use of national registers, resulting in a large unselected population with no loss to follow-up further supports the external validity of our findings. It should, however, be noted that our study comprises offspring born in Sweden, with only a minority of residents during the study period being of foreign descent (about 5.0-5.5%).37 Hence, results of this study might not necessarily be generalisable to other populations. Follow-up was limited to a maximum of 32 years of age, so we cannot make inferences about the influence of maternal smoking during pregnancy on risk of fractures in offspring in adulthood.

Several other potential limitations are also noteworthy. Firstly, information on maternal smoking during pregnancy was based on questions administered by midwives. Although results from previous studies support the validity of this measure of maternal smoking,34 35 this could have biased results towards the null as some women will not admit smoking during pregnancy or might underreport the number of cigarettes smoked. Also, exposure to maternal smoking was only assessed during the first trimester. Since women may give up or reduce the number of cigarettes smoked after the first trimester, this could also have led to an attenuation of potential associations. Secondly, this analysis only included fractures that resulted in inpatient or outpatient hospital care. Consequently, less severe fractures (not requiring hospital care) and unnoticed fractures were not included, and this will have resulted in an underestimation of the fracture incidence at any age. However, fractures requiring inpatient or outpatient hospital care are clinically most relevant. As the occurrence of undiagnosed or less severe fractures is unlikely to differ by maternal smoking, we would expect any bias resulting from it to have attenuated associations towards the null. Thirdly, fractures occurring at different stages of the life course might result from different causes. Before 1 year of age causes of fractures could include metabolic bone disease or osteopenia from in utero factors, genetic disorders, abuse, birth associated trauma, and other forms of accidental trauma.38 The relatively large proportion of skull or facial and femur fractures during the first year of life is consistent with patterns reported previously in infants,26 and suggests that a proportion of these fractures is due to birth related trauma38 among those susceptible to fractures because of brittle bones. Fractures later in life are also driven by hazardous environments and lifestyles to which offspring are exposed. Consequently, we might have underestimated the risks of fractures that are the direct consequence of inadequate skeletal mineralisation and suboptimal bone health with developmental origins. Nevertheless, regardless of the cause or level of trauma, susceptibility to fractures at any age depends on bone fragility.39 40 41 Fourthly, we did not have information on parental neglect, malnutrition, and physical activity levels in offspring, which could potentially confound associations between maternal smoking and risk of fracture in offspring in whole cohort analyses. Since these behavioural characteristics are likely to cluster within families, our within-sibship analyses will, at least to some extent, tackle residual confounding by these unmeasured factors. Fifthly, we found evidence of the smoking associated increase in fracture risk during the first year of life to be more pronounced closer to birth. We were, however, unable to analyse associations with fractures in neonates because of insufficient statistical power and the inability to differentiate between fractures due to birth trauma or to other causes. Lastly, the sibling comparison design also has potential limitations, including potential bias resulting from systematic misclassification of smoking discordance or concordance and confounding by factors that differ between siblings.42 43 To reduce this potential bias, we adjusted our analyses for several unshared familial environmental factors. Despite this, we cannot rule out the possibility that siblings within the same family experience different environments. For example, maternal smoking may be associated with temporary episodes of stressful life events or socioeconomic challenges that predisposes offspring to more hazardous environments than their siblings. This could give rise to possible residual confounding if these effects are not fully accounted for by the unshared familial factors in the within-sibship model. Within-sibship analyses are also less statistically efficient than whole cohort analyses, resulting in less precise estimates, especially during the first year of life when absolute numbers of fractures are low. We have been careful to focus on comparisons of the point estimates between the two methods rather than P values or whether the 95% confidence interval included the null value in the within-sibship analyses.

Comparison with other studies

The observed pattern of fracture incidence by site and by attained age in male and female offspring is broadly consistent with patterns described in previous research using diagnoses in primary care.44 Of note, the highest fracture rate was found around the ages of puberty, a period characterised by an asynchrony between the acceleration of height and bone mineral density.45

In this study, maternal smoking was associated with a slightly increased rate of fractures from age 5 years up to 32 years in whole cohort but not in within-sibship analyses. This is consistent with results from two birth cohort studies that found similar magnitudes of association between maternal and paternal (measured when their partners were pregnant) smoking during pregnancy with childhood bone mass,18 19 which implies residual confounding by unmeasured shared familial characteristics rather than a causal intrauterine effect of maternal smoking. Also, the lack of a dose dependent relation observed in this study and in a previous study16 relating maternal smoking to bone mass in prepubertal children argues against a causal intrauterine effect. Conversely, reported associations of smoking during pregnancy with neonatal bone mass14 15 and bone turnover46 have been more consistent. Our study extends these observations by showing the association with fractures before 1 year of age to be dose dependent and independent of both measured confounding factors and unmeasured familial factors shared by siblings. We found no evidence of maternal smoking being associated with risk of fractures in offspring between the ages of 1 and 5 years in whole cohort and within-sibship analyses, despite the larger statistical power to identify an association in this age group compared with the first year of life. These results suggest that maternal smoking only has a short term influence on the bone health of offspring, and that the amount of residual confounding by unmeasured shared familial factors tends to be less between ages 1 and 5 years.

A transient effect of maternal smoking on bone health of offspring during the first year of life is biologically plausible. Smoking during pregnancy reduces intestinal calcium absorption47 and influences the placenta,48 such that fetal development can be restricted through various mechanisms, including restricted blood flow. As growth slows postnatally and with maternal feeding ensuring more direct mineral supplies, the needs for effective bone mineralisation are likely to be better met after delivery.38 Indeed, it has been shown that by 2 years of age preterm born infants catch-up in growth, with bone mass being similar to that of infants born at term.49 Associations with fractures were independent of gestational age and weight at birth, suggesting that small size at birth does not explain these associations. As the association with fractures in early life appeared to be more pronounced closer to birth, this is also consistent with impaired fetal development associated with metabolic bone disease, a self-limiting condition that usually resolves during the first six months of life.38

Implications of the findings

Population level tobacco control programmes are effective in reducing rates of preterm births and low birth weights, as well as rates of hospital admissions for asthma and lower respiratory tract infections in children.50 51 Our results suggest that such interventions could potentially also reduce the risk of fractures in offspring before 1 year of age. However, we acknowledge that fractures in the first year of life are rare and the difference in fracture rate observed with smoking during pregnancy was small (0.31 per 1000 person years). Although fractures during the first year of life generally have a good prognosis, these fractures can cause considerable parental anxiety and discomfort for the infant.

In contrast with the findings for fractures in early life, we found no association between maternal smoking and fractures beyond 1 year of age in within-sibship analyses, despite the presence of weak associations in offspring aged 5 to 32 years in whole cohort analyses. These findings suggest that these latter associations are not explained by a biological intrauterine effect of maternal smoking but rather by unmeasured shared familial characteristics. Smoking behaviour and bone fragility or fractures are complex traits that are affected by environmental as well as genetic factors, but no studies to date have identified the common genetic basis of both traits. Hence, the extent to which the absence of within-sibship associations at older ages can be explained by shared genetic factors is unknown. It seems plausible that unmeasured shared environmental factors, including lifestyle, dietary choices, and other social and behavioural factors (that predispose children in families to grow up in hazardous environments) mainly account for the within-sibship results observed in those aged 5 years and older. Although these findings are an example of family level confounding, the prevention of smoking in parents could result in improved long term health among offspring for other reasons.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that maternal smoking during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of fractures before 1 year of age. Prenatal exposure to cigarette smoke, however, does not seem to have a longer lasting biological influence on risk of fracture later in childhood and up to early adulthood.

What is already known on this topic

Maternal smoking during pregnancy is an established risk factor for intrauterine growth restriction, and fetal skeletal growth seems to be particularly susceptible to the effects of maternal smoking

Evidence of the impact of maternal smoking during pregnancy on bone health and risk of fractures in children during different developmental stages of life is scarce and inconsistent

Previous research examining the association between intrauterine exposure to smoking and risk of fracture did not explore potential confounding by shared familial factors

What this study adds

Maternal smoking during pregnancy was associated with an increased fracture rate in offspring before 1 year of age and from age 5 to 32 years, but evidence of a dose dependent and within-sibship association was only observed for fractures before 1 year of age

These findings suggest an intrauterine effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy on fractures in offspring during the first year of life, whereas associations with fractures later in childhood and up to early adulthood seem to be confounded by familial factors shared by siblings

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Supplementary material: additional figures (1 and 2), methods, and tables (1-18)

Contributors JSB and SM conceived and designed the study. DAL and SC assisted with the methods. JSB did the data analysis. JSB and SM drafted the initial manuscript. All authors assisted with interpretation, commented on drafts of the manuscript, and approved the final version. JSB is the guarantor and attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This work was supported by the Örebro University Hospital Research Foundation Nyckelfonden (OLL-695391) and by the UK Economic and Social Research Council as a grant to the International Centre for Life Course Studies (ES/JO19119/1). DAL’s contribution to this work was supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MC_UU_00011/6) and National Institute for Health Research (NF-0616-10102). The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: support from Örebro University Hospital Research Foundation Nyckelfonden (OLL-695391) and the UK Economic and Social Research Council as a grant to the International Centre for Life Course Studies (ES/JO19119/1); DAL’s contribution to this work was supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MC_UU_00011/6) and National Institute for Health Research (NF-0616-10102); no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (reference No 2019-04143)

Data sharing: No additional data available. For statistical coding relating to analysis of the data, contact the corresponding author at judith.brand@regionorebrolan.se .

The lead author (JSB) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: There are no plans to directly disseminate the results of the research to study participants. The dissemination to the Swedish population (which constitutes the study population) and the broader public will be achieved through media outreach (ie, press release and publication in popular media).

References

- 1. Cnattingius S. The epidemiology of smoking during pregnancy: smoking prevalence, maternal characteristics, and pregnancy outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res 2004;6(Suppl 2):S125-40. 10.1080/14622200410001669187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kramer MS. Determinants of low birth weight: methodological assessment and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ 1987;65:663-737. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brand JS, Gaillard R, West J, et al. Associations of maternal quitting, reducing, and continuing smoking during pregnancy with longitudinal fetal growth: Findings from Mendelian randomization and parental negative control studies. PLoS Med 2019;16:e1002972. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jaddoe VW, Verburg BO, de Ridder MA, et al. Maternal smoking and fetal growth characteristics in different periods of pregnancy: the generation R study. Am J Epidemiol 2007;165:1207-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iñiguez C, Ballester F, Costa O, et al. INMA Study Investigators Maternal smoking during pregnancy and fetal biometry: the INMA Mother and Child Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol 2013;178:1067-75. 10.1093/aje/kwt085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wong PK, Christie JJ, Wark JD. The effects of smoking on bone health. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;113:233-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jauniaux E, Burton GJ. Morphological and biological effects of maternal exposure to tobacco smoke on the feto-placental unit. Early Hum Dev 2007;83:699-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bush PG, Mayhew TM, Abramovich DR, Aggett PJ, Burke MD, Page KR. A quantitative study on the effects of maternal smoking on placental morphology and cadmium concentration. Placenta 2000;21:247-56. 10.1053/plac.1999.0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lin FJ, Fitzpatrick JW, Iannotti CA, Martin DS, Mariani BD, Tuan RS. Effects of cadmium on trophoblast calcium transport. Placenta 1997;18:341-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baird J, Kurshid MA, Kim M, Harvey N, Dennison E, Cooper C. Does birthweight predict bone mass in adulthood? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 2011;22:1323-34. 10.1007/s00198-010-1344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martínez-Mesa J, Restrepo-Méndez MC, González DA, et al. Life-course evidence of birth weight effects on bone mass: systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 2013;24:7-18. 10.1007/s00198-012-2114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fall C, Hindmarsh P, Dennison E, Kellingray S, Barker D, Cooper C. Programming of growth hormone secretion and bone mineral density in elderly men: a hypothesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998;83:135-9. 10.1210/jc.83.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dennison EM, Cooper C, Cole ZA. Early development and osteoporosis and bone health. J Dev Orig Health Dis 2010;1:142-9. 10.1017/S2040174409990146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Godfrey K, Walker-Bone K, Robinson S, et al. Neonatal bone mass: influence of parental birthweight, maternal smoking, body composition, and activity during pregnancy. J Bone Miner Res 2001;16:1694-703. 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.9.1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harvey NC, Javaid MK, Arden NK, et al. SWS Study Team Maternal predictors of neonatal bone size and geometry: the Southampton Women’s Survey. J Dev Orig Health Dis 2010;1:35-41. 10.1017/S2040174409990055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jones G, Riley M, Dwyer T. Maternal smoking during pregnancy, growth, and bone mass in prepubertal children. J Bone Miner Res 1999;14:146-51. 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martínez-Mesa J, Menezes AM, Howe LD, et al. Lifecourse relationship between maternal smoking during pregnancy, birth weight, contemporaneous anthropometric measurements and bone mass at 18years old. The 1993 Pelotas Birth Cohort. Early Hum Dev 2014;90:901-6. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heppe DH, Medina-Gomez C, Hofman A, Rivadeneira F, Jaddoe VW. Does fetal smoke exposure affect childhood bone mass? The Generation R Study. Osteoporos Int 2015;26:1319-29. 10.1007/s00198-014-3011-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Macdonald-Wallis C, Tobias JH, Davey Smith G, Lawlor DA. Parental smoking during pregnancy and offspring bone mass at age 10 years: findings from a prospective birth cohort. Osteoporos Int 2011;22:1809-19. 10.1007/s00198-010-1415-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jones G, Hynes KL, Dwyer T. The association between breastfeeding, maternal smoking in utero, and birth weight with bone mass and fractures in adolescents: a 16-year longitudinal study. Osteoporos Int 2013;24:1605-11. 10.1007/s00198-012-2207-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Manias K, McCabe D, Bishop N. Fractures and recurrent fractures in children; varying effects of environmental factors as well as bone size and mass. Bone 2006;39:652-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jones IE, Williams SM, Goulding A. Associations of birth weight and length, childhood size, and smoking with bone fractures during growth: evidence from a birth cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:343-50. 10.1093/aje/kwh052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gage SH, Munafò MR, Davey Smith G. Causal Inference in Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) Research. Annu Rev Psychol 2016;67:567-85. 10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smith GD. Assessing intrauterine influences on offspring health outcomes: can epidemiological studies yield robust findings? Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2008;102:245-56. 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Parviainen R, Auvinen J, Pokka T, Serlo W, Sinikumpu JJ. Maternal smoking during pregnancy is associated with childhood bone fractures in offspring - A birth-cohort study of 6718 children. Bone 2017;101:202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Högberg U, Andersson J, Högberg G, Thiblin I. Metabolic bone disease risk factors strongly contributing to long bone and rib fractures during early infancy: A population register study. PLoS One 2018;13:e0208033. 10.1371/journal.pone.0208033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Donovan SJ, Susser E. Commentary: Advent of sibling designs. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:345-9. 10.1093/ije/dyr057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Board of Health and Welfare. The Swedish Medical Birth Register - A summary of Content and Quality. Stockholm: Centre for Epidemiology, 2003. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/en/statistics-and-data/registers/register-information/the-swedish-medical-birth-register/Accessed 29 November 2019.

- 29. Ekbom A. The Swedish Multi-generation Register. Methods Mol Biol 2011;675:215-20. 10.1007/978-1-59745-423-0_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy AK, et al. Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2016;31:125-36. 10.1007/s10654-016-0117-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brooke HL, Talbäck M, Hörnblad J, et al. The Swedish cause of death register. Eur J Epidemiol 2017;32:765-73. 10.1007/s10654-017-0316-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011;11:450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ludvigsson JF, Svedberg P, Olén O, Bruze G, Neovius M. The longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labour market studies (LISA) and its use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2019;34:423-37. 10.1007/s10654-019-00511-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mattsson K, Källén K, Rignell-Hydbom A, et al. Cotinine Validation of Self-Reported Smoking During Pregnancy in the Swedish Medical Birth Register. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18:79-83. 10.1093/ntr/ntv087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lindqvist R, Lendahls L, Tollbom O, Aberg H, Håkansson A. Smoking during pregnancy: comparison of self-reports and cotinine levels in 496 women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2002;81:240-4. 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810309.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rose DHE. The European socio-economic classification: a new social class schema for comparative Europen research. Eur Soc 2007;9:459-90 10.1080/14616690701336518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Statistics Sweden SCB. Summary of Population Statistics 1960-2018. https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/population/population-composition/population-statistics/pong/tables-and-graphs/yearly-statistics-the-whole-country/summary-of-population-statistics/ Accessed 29 November 2019.

- 38. Bishop N, Sprigg A, Dalton A. Unexplained fractures in infancy: looking for fragile bones. Arch Dis Child 2007;92:251-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Clark EM, Tobias JH, Ness AR. Association between bone density and fractures in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2006;117:e291-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Clark EM, Ness AR, Tobias JH. Bone fragility contributes to the risk of fracture in children, even after moderate and severe trauma. J Bone Miner Res 2008;23:173-9. 10.1359/jbmr.071010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Landin L, Nilsson BE. Bone mineral content in children with fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1983;(178):292-6. 10.1097/00003086-198309000-00040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Frisell T, Öberg S, Kuja-Halkola R, Sjölander A. Sibling comparison designs: bias from non-shared confounders and measurement error. Epidemiology 2012;23:713-20. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31825fa230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Keyes KM, Smith GD, Susser E. On sibling designs. Epidemiology 2013;24:473-4. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31828c7381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cooper C, Dennison EM, Leufkens HG, Bishop N, van Staa TP. Epidemiology of childhood fractures in Britain: a study using the general practice research database. J Bone Miner Res 2004;19:1976-81. 10.1359/jbmr.040902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bonjour JP, Chevalley T. Pubertal timing, bone acquisition, and risk of fracture throughout life. Endocr Rev 2014;35:820-47. 10.1210/er.2014-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Högler W, Schmid A, Raber G, et al. Perinatal bone turnover in term human neonates and the influence of maternal smoking. Pediatr Res 2003;53:817-22. 10.1203/01.PDR.0000057984.84206.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Krall EA, Dawson-Hughes B. Smoking increases bone loss and decreases intestinal calcium absorption. J Bone Miner Res 1999;14:215-20. 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zdravkovic T, Genbacev O, McMaster MT, Fisher SJ. The adverse effects of maternal smoking on the human placenta: a review. Placenta 2005;26(Suppl A):S81-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rubinacci A, Sirtori P, Moro G, Galli L, Minoli I, Tessari L. Is there an impact of birth weight and early life nutrition on bone mineral content in preterm born infants and children? Acta Paediatr 1993;82:711-3. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1993.tb12543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Faber T, Kumar A, Mackenbach JP, et al. Effect of tobacco control policies on perinatal and child health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017;2:e420-37. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30144-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hawkins SS, Baum CF, Oken E, Gillman MW. Associations of tobacco control policies with birth outcomes. JAMA Pediatr 2014;168:e142365. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material: additional figures (1 and 2), methods, and tables (1-18)