Abstract

Purpose:

To understand the influence of various acquisition parameters on the ability of CEST MR-Fingerprinting (MRF) to discriminate different chemical exchange parameters and to provide tools for optimal acquisition schedule design and parameter map reconstruction.

Methods:

Numerical simulations were conducted using a parallel computing implementation of the Bloch-McConnell equations, examining the effect of TR, TE, flip-angle, water T1 and T2, saturation-pulse duration, power, and frequency on the discrimination ability of CEST-MRF. A modified Euclidean distance matching metric was evaluated and compared to traditional dot product matching. L-Arginine phantoms of various concentrations and pH were scanned at 4.7T and the results compared to numerical findings.

Results:

Simulations for dot product matching demonstrated that the optimal flip-angle and saturation times are 30° and 1100 ms, respectively. The optimal maximal saturation power was 3.4 μT for concentrated solutes with a slow exchange rate, and 5.2 μT for dilute solutes with medium-to-fast exchange rates. Using the Euclidean distance matching metric, much lower maximum saturation powers were required (1.6 and 2.4 μT, respectively), with a slightly longer saturation time (1500 ms) and 90° flip-angle. For both matching metrics, the discrimination ability increased with the repetition time. The experimental results were in agreement with simulations, demonstrating that more than a 50% reduction in scan-time can be achieved by Euclidean distance-based matching.

Conclusions:

Optimization of the CEST-MRF acquisition schedule is critical for obtaining the best exchange parameter accuracy. The use of Euclidean distance-based matching of signal trajectories simultaneously improved the discrimination ability and reduced the scan time and maximal saturation power required.

Keywords: chemical exchange rate, chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST), magnetic resonance fingerprinting (MRF), optimization, pH, quantitative imaging

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI is a molecular imaging technique that is capable of detecting millimolar concentrations of exchangeable protons.1-4 The CEST contrast mechanism, when stemming from endogenous proteins and metabolites with exchangeable protons such as amine, amide, or hydroxyl groups, has provided clinical insights in a variety of disease pathologies. These include cancer,5-7 stroke,8,9 mitochondrial disorders,10 disc and cartilage degeneration studies,11,12 and neurodegenerative diseases.13-18 The same technique is even more sensitive when applied to exogenous materials19 involving the use of paramagnetic lanthanides,19-21 liposomes,22 or iodine containing substances.23

Several challenges still prevent CEST-MRI from reaching its full potential to become a routine clinical imaging technique. First, the predominantly used CEST analysis method is the Magnetization Transfer Ratio asymmetry (MTRasym24), which is mixed with non-CEST contrast contributions and highly dependent on the acquisition protocol parameters:

| (1) |

where S(±Δω) is the signal measured with saturation at offset ±Δω, and S0 is the unsaturated signal. A recent review on the application of CEST to clinical scanners has shown that there is a large heterogeneity in the acquisition parameters used by different medical centers,25 making the comparison of findings difficult. Moreover, the MTRasym does not take under consideration the effect of the nuclear Overhauser enhancement (NOE) mediated aliphatic protons, which can be highly dominant in the brain, and is prone to contamination from the semi-solid magnetization transfer (MT) pool26,27 and water T1 effects.28-31

Ideally, for providing the most useful estimation of the metabolite of interest, the actual physical CEST properties—proton exchange rate, and solute concentration should be mapped. In accordance, various efforts were previously taken to achieve quantitative CEST imaging32 such as the quantitation of exchange using saturation power (QUESP) or time (QUEST)33-35 and Omega plot36 methods. These methods exploit the dependency of the CEST signal on the saturation power (or saturation time) and fit the MTRasym for a single offset as a function of the saturation parameter to estimate the labile proton volume fraction and exchange rate. Although normalization of the MTRasym by the signal acquired at the negative offset frequency is intended to reduce the MT effect, it has been shown that the semisolid peak is actually asymmetric.37 Moreover, the QUESP type methods do not account for the NOE contribution. Alternatively, a multi-Lorentzian model can be fitted to the entire Z-spectrum, separating out the contribution of the CEST/MT/NOE pools.26,38,39 However, a single Z-spectrum-based Lorentzian fit provides only a semi-quantitative estimation of the pool features. To obtain the actual proton exchange rates and concentrations a multi-saturation power acquisition is required, which can take from tens of minutes to more than an hour.

Magnetic resonance fingerprinting (MRF) is a new paradigm for quantitative imaging.40 Originally presented for quantitative mapping of water T1, T2 and B0, this technique enables the fast and simultaneous mapping of several magnetic properties. It uses a pseudo-random acquisition schedule, which yields unique signal trajectories, capable of differentiating between various combinations of tissue properties. At the reconstruction step, the experimental data is compared to a Bloch equation-based simulated dictionary, and the best match for each trajectory yields an estimated set of tissue properties.41 Recently, MRF was expanded and modified for CEST imaging42-44 whereby the Bloch-McConnell equations are used to generate a reference dictionary, and a pseudorandom acquisition schedule with varied saturation power and/or times is used for obtaining signal trajectories and determining the exchange rate and volume fraction of the solute of interest. In the realm of quantitative CEST imaging, CEST-MRF possess several important advantages: the acquisition time is much shorter than the alternatives (a few minutes); it takes under consideration the effect of various solute pools, without assuming any symmetry; and it can simultaneously output the fully quantitative properties of several-pools.42 Although preliminary results were promising, the incorporation of CEST-MRF in routine studies requires understanding the dependency of the discrimination ability on various pulse-sequence parameters. Unlike classic water-pool MRF, which relies on non-steady state evolution of the magnetization, CEST requires considerable amplification of the labile proton signal and typically requires long saturation times leading to steady-state magnetization. Hence, it is essential to evaluate the limitations and technical considerations involving CEST-MRF acquisition schedules.

In the present study, the effect of various acquisition properties on the discrimination ability of CEST-MRF is systematically examined toward an optimized pulse sequence. Moreover, a CEST-MRF specific Euclidian distance-matching metric is suggested, and compared to the conventional dot product metric, for improved parameter map reconstruction. We include numerical simulations in addition to in vitro L-Arg phantom studies at 4.7T.

2 ∣. METHODS

2.1 ∣. Simulated CEST scenarios

Three main representative CEST scenarios were numerically investigated, under 4.7T field conditions:

“Scenario A”: Amide exchangeable solute proton with a slow exchange rate but relatively high proton volume fraction, analogous to the endogenous amide protons observed in vivo. A 3-pool simulation model was used that included the endogenous amide proton pool (chemical shift of 3.5 ppm), semi-solid proton pool (chemical shift of −2.5 ppm), and water proton pool.

“Scenario B”: Amine exchangeable proton with a medium to fast chemical exchange rate but relatively dilute proton volume fraction, analogous to applications such as imaging endogenous creatine,45 iodine-based pH probes,23 or CEST reporter genes.46 A 2-pool case was simulated, with the solute chemical shift set at 3 ppm.

“Scenario C”: To explore the general effect of water T1 and T2 changes on the optimized parameters, and to facilitate convenient validation using imaging phantoms, a third scenario was examined identical to scenario B but with longer relaxation times. Alterations in water T1 and T2 are expected in some clinical cases (e.g., edema), during the use of mixed iron-CEST agents,47 and for drastic pH changes involving exogenous materials.48 The simulated multi-pool properties for each of the 3 scenarios are detailed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Relaxation time and chemical exchange parameters for the examined CEST application scenarios

| Scenario |

A |

B |

C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Description | 3-pool: water, amide proton, and semisolid MT |

Diluted solutes in the medium to fast exchange rate regime (2-pool) |

Diluted solutes in the medium to fast exchange rate regime (2-pool) + long water relaxation times |

| Water T1 (ms) | 1450 | 1450 | 2450 |

| Water T2 (ms) | 50 | 50 | 600 |

| Solute T1 (ms) | 1450 | 1450 | 2450 |

| Solute T2 (ms) | 1 | 40 | 40 |

| ksw (Hz) | 5:5:150 | 5:5:1000 | 5:5:1000 |

| Solute concentration (mM) | 100:50:1000 | 10:5:120 | 10:5:120 |

| Exchangeable protons per solute | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Off-set frequency (ppm) | 3.5 | 3 | 3 |

| Semi-solid T1 (ms) | 1450 | - | - |

| Semi-solid T2 (ms) | 0.04 | - | - |

| Semi-solid concentration (M) | 13.2 | - | - |

| kssw (Hz) | 30 | - | - |

2.2 ∣. Bloch-McConnell-based dictionary generation

Dictionaries of simulated signal intensity trajectories were generated using a Pade approximation49 for the numerical solution of the Bloch-McConnell equations. A 3-pool system was simulated using 3 components for water, CEST, and semisolid MT as suggested previously,50,51 forming a 7 × 7 matrix equation. For acceleration, the simulation was implemented in C++ using eigen52 for linear algebra operations and openMP53 for multi-threading. The source code was compiled with g++ 7.3 on an Ubuntu OS and is callable as a mex function in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts).

2.3 ∣. Matching metric

The pattern matching methodology, i.e., the assignment of the measured trajectory to a specific dictionary entry, determines the inherent discrimination of a given schedule. In this study, 2 matching metrics were used:

-

1.

Vector dot product (DP) after 2-norm normalization40:

| (2) |

where e denotes an experimental signal trajectory and d denotes the dictionary entry vector.

-

2.

Euclidean distance (ED) with trajectory normalization by M0 (the unsaturated reference signal) and the trajectory length (Nt):

| (3) |

where:

| (4) |

where M0e and M0d are the unsaturated reference signals for the experimental signal trajectory and the dictionary entry, respectively. Note that the normalization by Nt does not have an effect on the optimization (for a given trajectory length) but is used to bound ED to the range [0, 1], as in DP.

2.4 ∣. Discrimination ability criteria

An ideal acquisition schedule will have a perfect match between the experimentally obtained trajectory and its ground truth corresponding dictionary entry while having a poor match with any other entry. To quantify the discrimination ability we have used the following loss measures, each suitable for a specific matching metric:

-

1.

Off-diagonal Frobenius norm dot product loss54 (for dot product matching):

| (5) |

where D is the dictionary dot product matrix, consisting of the DP values for all ND combinations of dictionary entries, I is the identity matrix, and ∥ ∥f is the Frobenius norm. Intuitively, low DPloss values indicate that non-identical trajectories are close to orthogonal, hence the discrimination is optimized.

-

2.

Off-diagonal Frobenius norm Euclidean distance loss (for Euclidean distance matching):

| (6) |

where E is the dictionary Euclidean distance matrix, containing ED values for all combinations of dictionary entries. The EDloss was designed to provide a qualitatively similar output to DPloss, namely low values indicate better discrimination, while 1 indicates no discrimination.

-

3.

Monte Carlo simulation of noise propagation. White Gaussian noise (25 dB) was added to the dictionary and the resulting trajectories matched to the original noiseless dictionary. The process was repeated 100 times, and the root-mean-squared errors (RMSE) for the exchange rate and proton volume fraction matching were calculated. This measure was used for an acquisition schedule truncation study whereby the number of schedule iterations was optimized as it has been recently found useful for that purpose.55 Moreover, DPloss and EDloss are not directly comparable and ED is biased when the number of iterations Nt is varied.

2.5 ∣. Examining the dependence of the discrimination ability on the acquisition parameters

The influence of various acquisition parameters on the discrimination ability was numerically investigated. Since a relatively large parameter space affects the obtained signals, we focused the evaluations on 2 varied parameters at each step (while keeping all others fixed). The baseline acquisition schedule was set to the published version,42 which had a pseudorandom sequence of 30 saturation powers in the range of 0-6 μT, TR = 4 s, TE = 21 ms, flip angle (FA) = 60°, saturation time (Tsat) = 3 s, and a saturation offset frequency fixed to the solute offset frequency. The baseline saturation powers and the acquisition parameters examined are shown in Supporting Information Figure S1. Initially, the joint effect of varying the maximal saturation power and Tsat was examined by rescaling the entire baseline schedule to have a maximum varying from 0.2 to 6 μT in 0.2 μT increments and Tsat from 100 to 3900 ms in 100 ms increments. Next, the optimal B1max and Tsat values were used, and the FA and TR were varied from 5° to 90° in 5° increments and from 100 ms higher than Tsat to 8 s in 100 ms increments, respectively. Finally, the optimal B1max and Tsat values were again used with TR and FA fixed to their baseline values, but the saturation offset varied between 1 ppm lower than the solute offset to 1 ppm higher than the solute offset, in 0.1 ppm increments and the TE varied between 20 to 100 ms in 10 ms increments. For each combination of varied parameters, the DPloss and the EDloss were calculated, and the respective 3-D surface plot with its projected loss iso-contour lines was examined.

2.6 ∣. Optimization of the schedule length

To investigate the feasibility of reducing the number of schedule iterations and thus further shorten the acquisition time, dictionaries for the baseline schedule were re-created with Nt varied from 1 to 30. This same schedule was used for both matching metrics to facilitate easy comparison. The DPloss was then calculated to predict the discrimination ability using the dot product. We note that the equivalent calculation for EDloss is biased by Nt and therefore cannot be used to optimize the schedule length. To nonetheless compare the predicted performance for both matching methods, a Monte Carlo simulation of noise propagation was performed.

2.7 ∣. Phantom study

The aim of the phantom study was to test the validity of the optimal acquisition parameters predicted by the loss measures, by experimentally performing the schedule length optimization study depicted above. A set of 3 L-arginine phantoms were used, similarly to,42 containing a total of 9 vials of 25-100 mM dissolved L-Arg in a buffer titrated to a range of 4-6 pH. The vials were surrounded by 2% agarose gel and imaged at room temperature. Single-slice, singleshot CEST-MRF spin-echo EPI was acquired on a 4.7T MRI (Bruker, MA), with a 35-mm inner diameter birdcage volume coil (Bruker Biospin). The baseline acquisition schedule parameters (Section 2.5) were used, with the addition of a preceding M0 scan. For direct comparison between the Euclidean distance and the dot product metrics reconstructions from the same scan, the M0-scan was followed by a single 15s repetition time.

As a reference ground truth, quantitative estimation of the solute properties was performed using QUESP,33 employing an EPI schedule with TE = 21 ms, TR = 10 s, FA = 90°, at saturation frequency offsets of ±3 ppm and 0-6 μT powers in 1 μT increments. T1 maps were generated using variable repetition time images, acquired with TR = 200, 400, 800, 1500, 3000, and 5000 ms, TE = 7.5 ms, and FA = 90°. T2 maps were generated from multi-echo spin-echo images, with a FA = 90° , TE = 9 ms, TR = 2000 ms, and 25 echoes between 9 and 225 ms. All imaging protocols had an identical geometry with the FOV set to 37 × 37 mm, and an isotropic pixel size of 1 mm.

2.8 ∣. Experimental data analysis

The CEST-MRF data was reconstructed into quantitative exchange rate and concentration maps by pixel-wise matching the experimental trajectories to a dictionary comprised of the parameter combinations appearing in Table 1, “scenario C”. The solute exchange rate range was extended to 1400 Hz, to account for the high pH L-Arg vials.42 The dot product and the Euclidean distance metrics were both employed, with the normalization performed as described in Section 2.3. T1 and T2 exponential fitting were performed using a custom-written program. To obtain ground truth exchange rate values, pixel-wise exchange rate fitting of the QUESP data was performed with the known solute concentrations and measured water T1 given as fixed inputs.34 For comparison, simultaneous fitting of the QUESP data for both the exchange rate and concentration was also performed, by allowing both parameters to vary. Finally, the RMSE between the CEST-MRF exchange rate and concentration maps and the respectively measured concentration and QUESP exchange rates (estimated with input ground truth concentrations) were calculated, using regions of interest (ROIs) of 36 mm3. The mean ± SD RMSE for all 3 phantoms was calculated for each schedule length case. Differences were evaluated by Student’s t test with P < 0.05 considered as statistically significant. All calculations and fittings were performed using MATLAB.

3 ∣. RESULTS

3.1 ∣. Dictionary simulation

A compiled parallel-computing implementation of the Bloch-McConnell equation simulations was used to generate the MRF dictionaries, comprised of the parameter combinations described in Table 1. The synthesis times was approximately 8 times faster than using the previously published sparse matrix implementation42 on the same computer. For example, generation of the ~670,000 entry dictionary described in42 took 7.64 min, instead of 61 min on an Intel Xeon desktop computer equipped with four 2.27 GHz CPUs. It should be noted that the synthesis time could be further shortened by using a computer with more CPU cores.

3.2 ∣. The dependence of the discrimination ability on the acquisition parameters

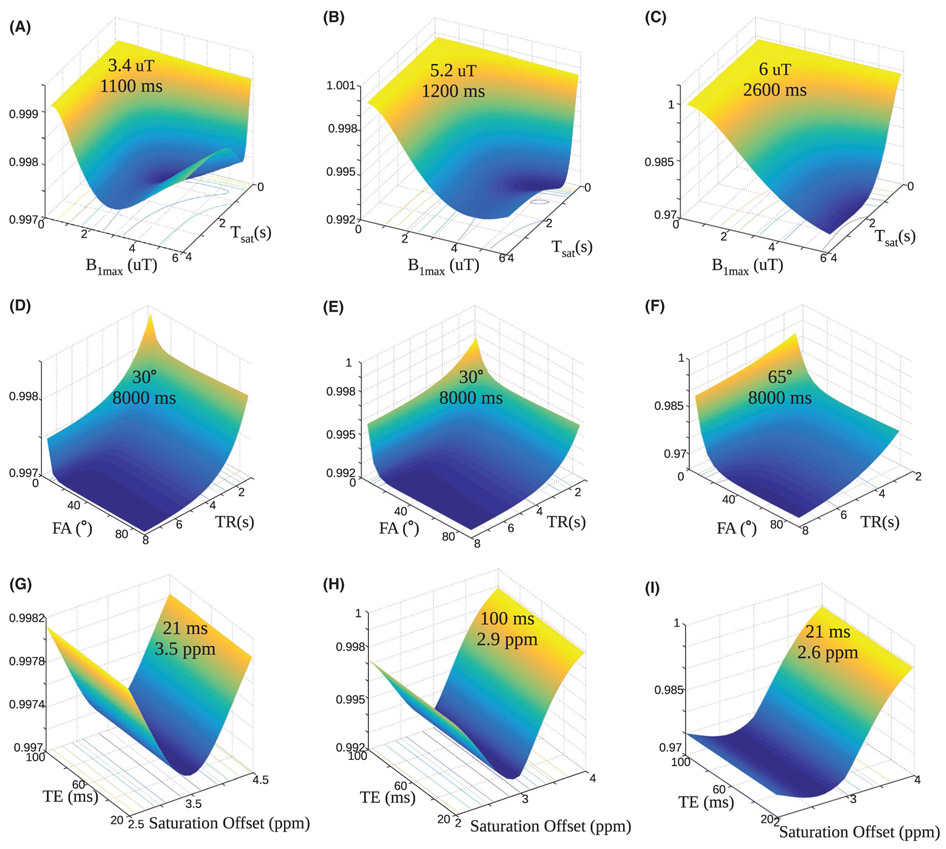

The surface plots describing the discrimination ability for the dot product metric are presented in Figure 1. The optimal saturation times were 1100-1200 ms for scenarios A and B and 2600 ms for scenario C, which simulated longer water T1 and T2. The optimal maximum saturation powers were 3.4, 5.2, and 6 μT respectively, for scenarios A, B, and C. In all 3 scenarios, the discrimination increased (loss decreased) with increasing flip-angle till approximately 20° and then plateaued with very slightly increasing loss for greater flip-angles. The discrimination ability continuously improved with increased repetition times in all cases. The echo time had no distinct effect on the loss, causing only slight variations. For the amide and semi-solid scenario A, the optimal saturation frequency offset was the same as the amide pool frequency (3.5 ppm), as expected. Interestingly, the optimal offset shifted 0.1 ppm from the simulated solute offset for scenario B, and 0.4 ppm for scenario C.

FIGURE 1.

Dependence of the dot product loss on the acquisition parameters. The surface plots with projected loss iso-contours describe the effect of the maximal saturation power and the saturation time (Tsat) (A-C), the flip angle (FA) and TR (D-F), and the TE and saturation frequency offset (G-I), on the DPloss, for scenarios A (left column), B (center column), and C (right column). In all images, the z-axis represents the DPloss, which is also color coded from blue to yellow. The optimal combination for each examined parameter pair is given in the surface plot

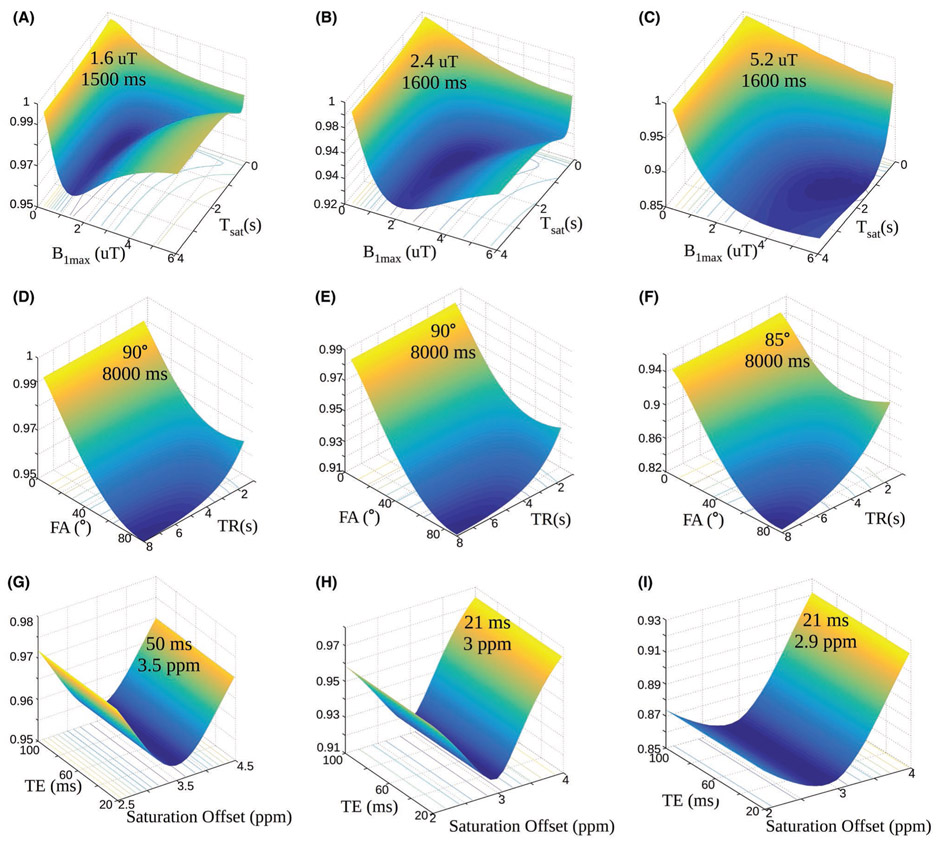

The surface plots describing the parameter discrimination ability for the Euclidean distance metric are presented in Figure 2. The optimal saturation time was 1500 ms for scenario A, and 1600 ms for both scenario B, and C. Similar to the dot product optimization, the optimal maximum saturation power increased from case A to B, and C, although the required powers were lower (1.6, 2.4, and 5.2 μT, respectively). The optimal TR was again 8000 ms for all scenarios, although a clear flip-angle dependency was evident here, yielding minimal EDloss for FA = 90°. The echo time had a minor influence on the loss, as can also be inferred from the straight and parallel loss iso-contours (Figure 2G-I). This may stem from the normalization of the trajectories and is in agreement with previous reports on the influence of TE on the CEST effect.56 A minimal echo time should, nonetheless, be chosen for optimal experiment SNR (TE = 21 ms was obtained for most cases in Figures 1 and 2G-I). The optimal saturation frequency was the same as the solute frequency for scenarios A and B, with a slight 0.1 ppm shift for scenario C.

FIGURE 2.

Dependence of the Euclidean distance loss on the acquisition parameters. The surface plots with projected loss iso-contours describe the effect of the maximal saturation power and the saturation time (Tsat) (A-C), the FA and TR (D-F), and the TE and saturation frequency offset (G-I), on the EDloss, for scenarios A (left column), B (center column), and C (right column). In all images, the z-axis represents the EDloss, which is also color coded from blue to yellow. The optimal combination for each examined parameter pair is given in the surface plot

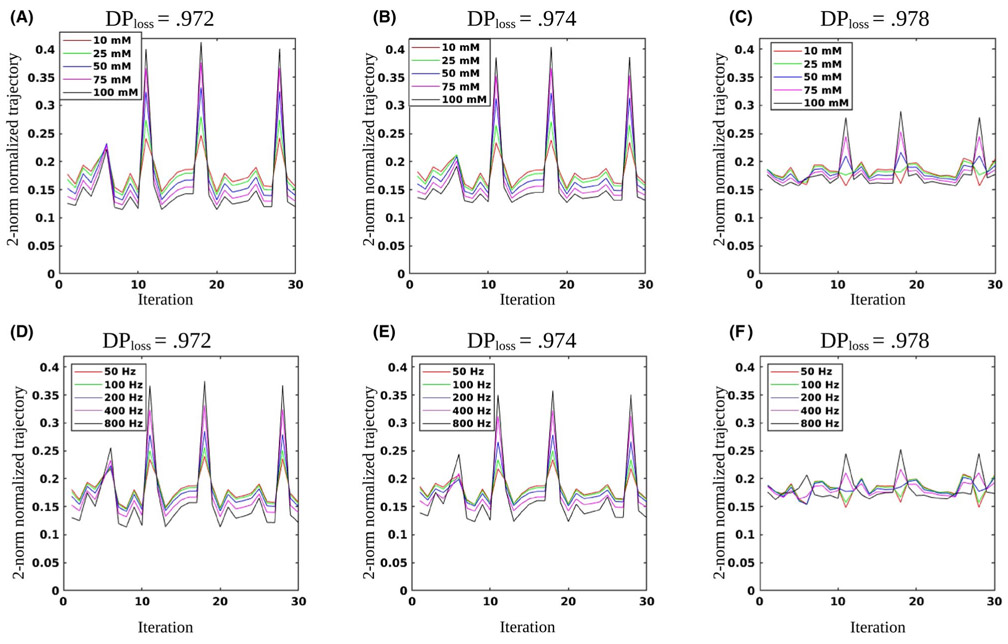

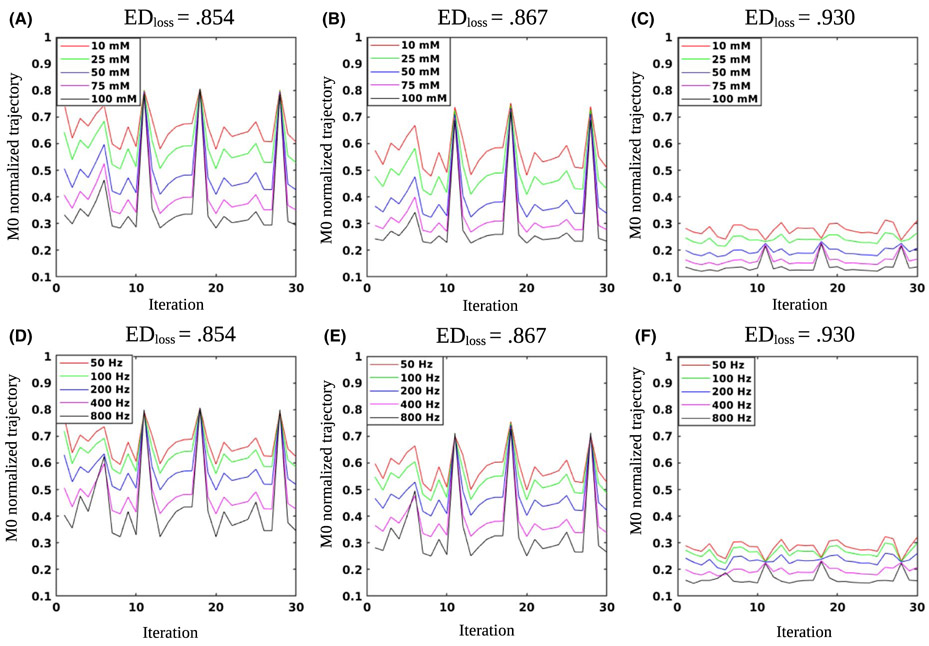

The morphological differences between trajectories of various acquisition parameter combinations are shown in Figure 3 (for the dot product metric), and Figure 4 (for the Euclidean distance metric). Visually, the differences in trajectories for various CEST properties mostly manifested as amplitude scaling rather than distinctly different patterns. For both metrics, a pronounced deviation from the optimal set found was manifested as smaller amplitude differences between trajectories, accompanied by a reduced loss value. Although not optimal, the trajectories of the baseline acquisition schedule were relatively similar in amplitude (and in the resulting loss) to the best set of parameters, explaining the previously good results reported using this acquisition parameter set.42

FIGURE 3.

Exemplary trajectories for different combinations of acquisition schedule parameters normalized by the 2-norm (for dot product matching). In (A-C), the exchange rate was fixed at 400 Hz, and the solute concentration varied from 10 to 100 mM. In (d-f), the solute concentration was fixed on 50 mM, and the exchange rate varied from 50 to 800 Hz. The left column represents a close to optimal acquisition parameters combination (TR was set to 4s instead of 8s for speed considerations), with saturation time (Tsat) = 2600 ms, FA = 60°, saturation offset = 2.6 ppm, TE = 21 ms, maximum saturation power = 6 μT. The center column represents the baseline acquisition schedule (Tsat = 3000 ms, saturation offset = 3 ppm, see Section 2.5), and the right column represents the same schedule, but with shorter saturation time and excitation flip angle (FA = 15°, and Tsat = 1500 ms). The same CEST properties of scenario “C” were used for all trajectories

FIGURE 4.

Exemplary trajectories for different combinations of acquisition schedule parameters normalized by M0 (for Euclidean distance matching). In (A-C), the exchange rate was fixed at 400 Hz, and the solute concentration varied from 10 to 100 mM. In (D-F), the solute concentration was fixed on 50 mM, and the exchange rate varied from 50 to 800 Hz. The left column represents a close to optimal acquisition parameters combination (TR was set to 4s instead of 8s for speed considerations), with saturation time (Tsat) = 1600 ms, FA = 90°, saturation offset = 2.9 ppm, TE = 21 ms, maximum saturation power = 5.2 μT. The center column represents the baseline acquisition schedule (Tsat = 3000 ms, saturation offset = 3 ppm, see Section 2.5), and the right column represents the same schedule, but with shorter saturation time and excitation flip angle (FA = 15°, and Tsat = 1500 ms). The same CEST properties of scenario “C” were used for all trajectories

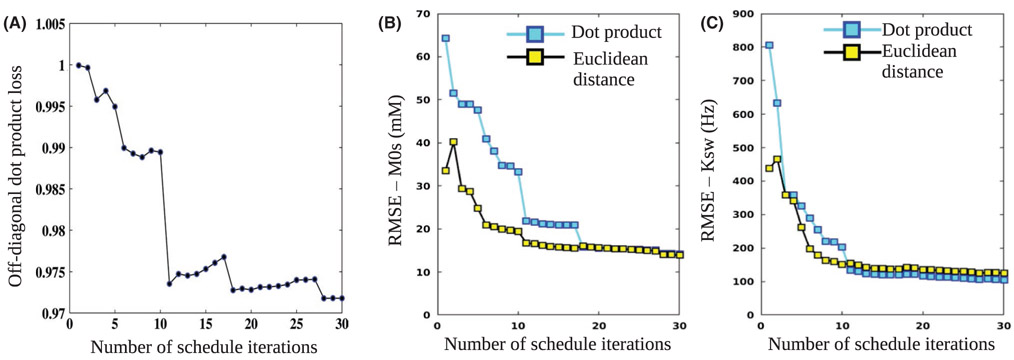

3.3 ∣. Optimizing the schedule length

The resulting DPloss values for different schedule lengths are shown in Figure 5A. A step-shaped improvement in the discrimination ability was demonstrated, with a leap in performance at Nt = 11. The average RMSE values for matching the solute concentration are shown in Figure 5B. The dot product related RMSE presented a similar step-like shape, with a similar leap at Nt = 11. The Euclidean distance RMSE were lower than that of the dot product RMSE for most schedule lengths. Similar to the dot product results, the Euclidean distance RMSE predicted a discrimination ability improvement at Nt = 11. However, the general convergence to the minimum RMSE was much faster, with less discrimination improvement after the 11th iteration (milder slope). For the solute exchange rate (ksw) (Figure 5C), the Euclidean distance RMSE was again lower than the dot product RMSE for short schedule lengths, but the errors converged to a similar or slightly higher value at the final iteration.

FIGURE 5.

Optimization of the schedule length. A, DPloss values for the baseline schedule with varied lengths. Note the step-like shape, predicting noticeable performance improvement at Nt = 11, with further improvement when additional iterations are added. B, Solute concentration (M0s) RMSE, comparing the dot product and Euclidean distance-based matching. C, Proton exchange rate (ksw) RMSE for both matching metrics

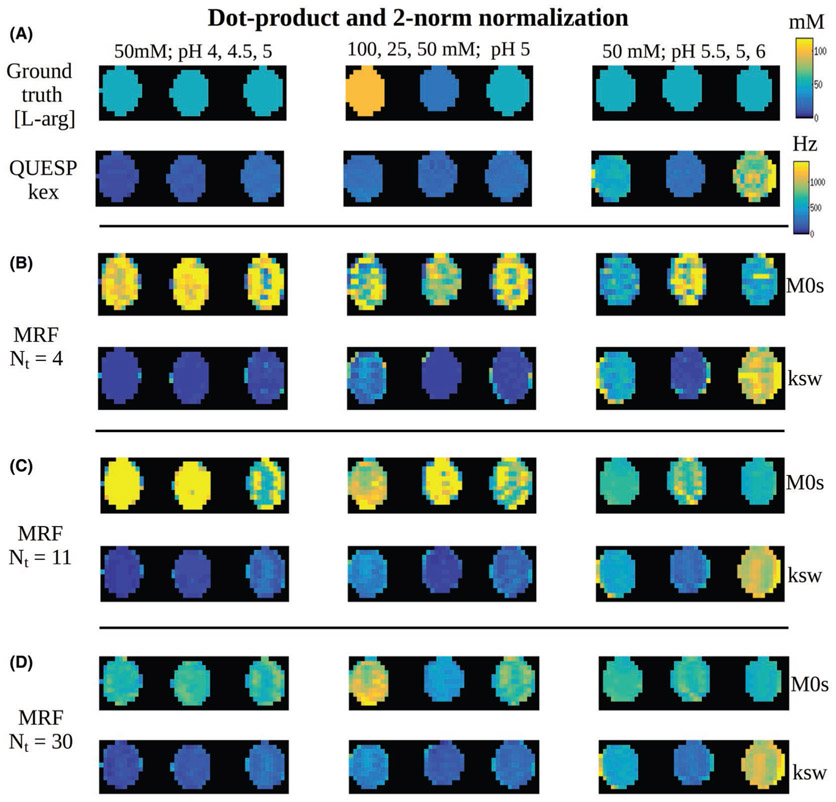

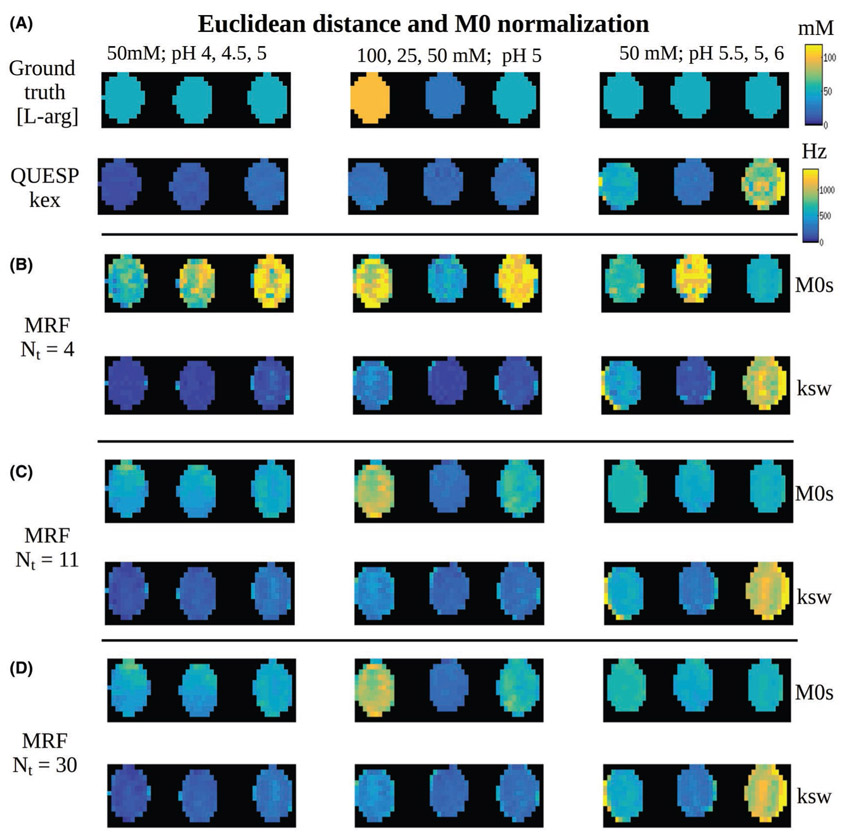

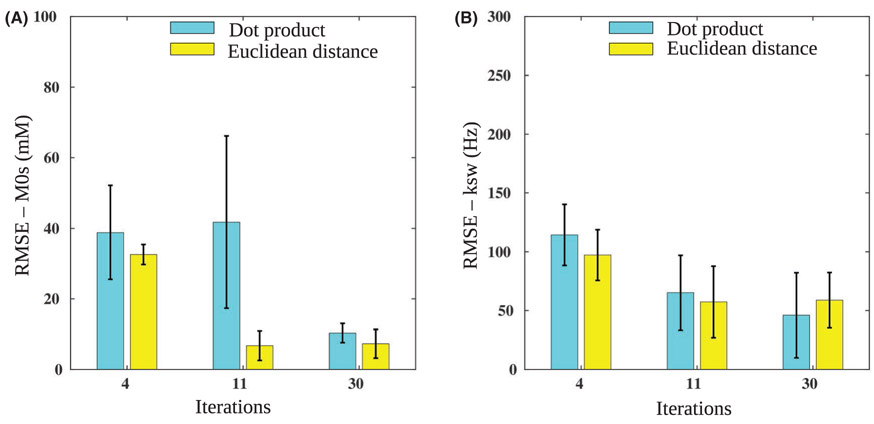

3.4 ∣. Phantom study

The measured solute concentrations and the QUESP exchange rate images (generated with the known concentrations as input) for the 9 imaged vials are shown in Figure 6A. The dot product matching of the CEST-MRF trajectories using 4 schedule iterations yielded poor results, with only a few vials matched correctly (Figure 6B). When 11 iteration long trajectories were used, the results have improved, although significant errors are still visible. Using all 30 iterations, the errors are further reduced, yielding a more similar output to QUESP results. The corresponding results for the Euclidean distance-based matching are shown in Figure 7. As can clearly be seen, using this metric the images converge to the QUESP results much faster, as most noticeable at Nt = 11. The visual difference between the matching outcomes using 11 or 30 iterations is barely visible (as predicted by the numerical simulation in Figure 5). The quantitative analysis of the experimental phantom RMSE, compared to the reference QUESP images is shown in Figure 8. The RMSE for the Euclidean distance matched images of solute concentration is significantly reduced at Nt = 11 compared to only 4 iterations, whereas using 30 iterations has not yielded significant improvement. The Euclidean distance-based solute concentration RMSE are also significantly lower than the corresponding dot product RMSE at Nt = 11. The dot product-based solute concentration RMSE was not significantly reduced at Nt = 11 compared to Nt = 4 but was significantly reduced at Nt = 30. Although similar trends were obtained for the exchange rate RMSE, no significant differences were observed. The quantitative values for all phantom vials are reported in Table 2.

FIGURE 6.

Dot product matching of CEST-MRF phantom images. A, Reference of known solute concentration (top) and QUESP proton exchange rate images (bottom) for the 9 imaged vials. B-D, Dot product reconstructed CEST-MRF images for 4, 11, and 30 iterations, respectively. The same color map and dynamic range (top-right) were used for all images

FIGURE 7.

Euclidean distance matching of CEST-MRF phantom images. A, Reference of known solute concentration (top) and QUESP proton exchange rate images (bottom) for the 9 imaged vials. B-D, Euclidean distance reconstructed CEST-MRF images for 4, 11, and 30 iterations, respectively. The same color map and dynamic range (top-right) were used for all images

FIGURE 8.

Phantom study quantitative analysis. RMSE values for solute concentration (M0s) (A), and chemical exchange rate (ksw) (B), using the baseline schedule with varied lengths. Note the significant performance improvement at Nt = 11 for Euclidean distance M0s matching (A), significantly lower than the dot product respective values. No significant improvement occurs for the Euclidean distance at Nt = 30, suggesting the schedule can be shortened without harming performance

TABLE 2.

Comparison of the CEST-MRF dot product or Euclidean distance matched L-Arg concentrations and amine proton chemical exchange rates (kex) with QUESP measured values for the various phantom vials

| Ground truth concentration |

QUESP with ground truth concen- tration as input |

Dot product with Nt = 4 |

Dot product with Nt = 11 |

Dot product with Nt = 30 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [L-arg](mM) | kex (Hz) | [L-arg] (mM) | kex (Hz) | [L-arg] (mM) | kex (Hz) | [L-arg] (mM) | kex (Hz) |

| 50 | 104.6 ± 8.4 | 100.6 ± 13.4 | 82.4 ± 2.5 | 120.0 ± 0.0 | 70.8 ± 5.8 | 56.3 ± 4.5 | 105.1 ± 17.8 |

| 50 | 138.7 ± 13.7 | 109.6 ± 11.0 | 84.0 ± 2.8 | 118.3 ± 6.9 | 92.1 ± 8.8 | 61.7 ± 4.0 | 136.8 ± 15.9 |

| 50 | 240.7 ± 17.3 | 93.2 ± 34.9 | 106.4 ± 47.3 | 79.2 ± 29.4 | 218.5 ± 86.0 | 59.0 ± 8.5 | 248.2 ± 62.0 |

| 100 | 268.1 ± 30.3 | 80.7 ± 28.6 | 305.6 ± 106.2 | 89.6 ± 13.3 | 365.3 ± 62.3 | 88.9 ± 11.8 | 369.6 ± 62.0 |

| 25 | 206.7 ± 29.3 | 74.8 ± 15.3 | 83.9 ± 2.1 | 109.3 ± 16.3 | 79.0 ± 13.7 | 39.3 ± 3.6 | 148.9 ± 19.9 |

| 50 | 262.3 ± 24.5 | 93.8 ± 25.9 | 87.2 ± 3.9 | 82.5 ± 24.4 | 202.8 ± 62.6 | 64.6 ± 8.2 | 235.3 ± 46.0 |

| 50 | 569.3 ± 47.4 | 47.5 ± 11.7 | 540.1 ± 91.6 | 60.1 ± 2.2 | 524.4 ± 38.0 | 60.1 ± 2.2 | 526.7 ± 37.6 |

| 50 | 255.2 ± 26.3 | 93.2 ± 31.8 | 124.0 ± 124.2 | 71.4 ± 20.4 | 241.7 ± 80.3 | 59.9 ± 7.7 | 267.6 ± 67.4 |

| 50 | 887.4 ± 144.9 | 52.9 ± 25.4 | 1075.0 ± 167.9 | 53.6 ± 2.8 | 982.5 ± 93.4 | 52.9 ± 2.5 | 990.0 ± 91.9 |

| QUESP simultaneous estimation of [L-arg] and kex | Euclidean distance: Nt = 4 | Euclidean distance: Nt = 11 | Euclidean distance: Nt = 30 | ||||

| 32.0 ± 3.5 | 171.7 ± 19.4 | 56.4 ± 9.8 | 82.8 ± 7.2 | 44.7 ± 4.9 | 114.7 ± 17.1 | 44.0 ± 6.0 | 120.6 ± 21.0 |

| 31.6 ± 3.1 | 233.6 ± 20.0 | 79.7 ± 16.0 | 83.5 ± 9.5 | 43.9 ± 5.6 | 159.3 ± 18.1 | 42.4 ± 6.4 | 171.1 ± 23.5 |

| 34.9 ± 2.7 | 374.9 ± 33.4 | 97.8 ± 20.4 | 130.3 ± 50.3 | 47.2 ± 5.1 | 273.9 ± 63.0 | 46.8 ± 4.7 | 282.4 ± 61.1 |

| 67.7 ± 10.3 | 446.8 ± 49.1 | 98.9 ± 17.8 | 311.5 ± 76.3 | 81.7 ± 8.0 | 381.9 ± 55.8 | 81.1 ± 7.7 | 390.1 ± 54.8 |

| 13.1 ± 1.9 | 473.3 ± 36.7 | 43.2 ± 8.1 | 82.5 ± 10.2 | 20.8 ± 2.5 | 186.0 ± 25.1 | 20.0 ± 2.4 | 205.3 ± 26.3 |

| 37.1 ± 4.5 | 383.4 ± 51.0 | 108.5 ± 8.8 | 120.6 ± 16.6 | 56.9 ± 6.4 | 246.5 ± 47.1 | 56.5 ± 6.7 | 256.5 ± 47.0 |

| 48.6 ± 3.1 | 597.1 ± 56.0 | 58.3 ± 6.1 | 509.3 ± 78.5 | 55.3 ± 1.2 | 546.3 ± 37.4 | 55.6 ± 1.6 | 554.0 ± 43.4 |

| 37.2 ± 4.1 | 367.4 ± 29.2 | 100.7 ± 21.5 | 140.8 ± 88.2 | 46.0 ± 4.6 | 296.7 ± 57.1 | 45.6 ± 4.6 | 307.9 ± 59.0 |

| 45.8 ± 3.4 | 1076.5 ± 83.8 | 50.4 ± 3.2 | 1022.4 ± 143.8 | 50.3 ± 2.9 | 1020.3 ± 96.1 | 51.1 ± 2.7 | 1003.8 ± 114.4 |

4 ∣. DISCUSSION

The optimization of CEST-MRF involves 2 competing mechanisms. On the one hand, traditional CEST imaging generally favors steady-state-like, high solute-signal conditions. On the contrary, classical MRF is typically characterized by low-SNR non-steady state rapidly changing spin dynamics. The optimal parameters found (Figures 1 and 2), contain elements from both concepts. While the resulting saturation times (1100–1600 ms) were shorter than those typically used in continuous wave pulse saturation CEST experiments,23 the optimal repetition time was at least 3 times longer than the water T1. Nevertheless, to retain a short acquisition time with satisfying accuracy, a compromise in TR duration (TR = 4 s) can be considered, with only a small sacrifice in discrimination ability. The compensation for speed-loss may come from the small number of schedule iterations required; 11-30 iterations for CEST-MRF. The inherent conflict between non-steady state conditions and the requirement for sufficient CEST-SNR was also evident in the trajectories associated with the various sets of schedule parameters (Figures 3 and 4). While the patterns become more distinct for shorter saturation times, indicating the conditions are further away from steady-state, the signal amplitudes get smaller and the loss is actually increased, corresponding to decreased parameter discrimination (Figure 3C,F).

The optimal acquisition parameters found in this study are in general agreement with previously published CEST-MRF sequences. For example, the saturation power and time used for dot product matching by Cohen et al42 (Tsat = 3 s, maximal B1 = 6 μT) are very close to the optimal parameters found here (Tsat = 2.6 s, B1 = 6 μT) for a similar CEST scenario and are on the same loss iso-contour (Figure 1C). The optimal TE and FA are also very similar (FA = 60°, TE = 21 ms in42; FA = 65°, TE = 21 ms in this study). Importantly, the optimization for the amide proton imaging 3-pool scenario, demonstrated that lower saturation power and times could have been used in previous brain in vivo CEST-MRF efforts.42 Interestingly, in some cases (Figures 1H-I and 2I) the optimal saturation frequency offset was slightly shifted with respect to the solute offset, suggesting that incorporating several saturation offsets in the schedule could be useful. The possible origin of these shifts is the fast exchange rate involved, causing a broader CEST peak that is shifted closer to the water peak. The comparison with the results published in43 is more difficult, as a different range of exchange rates was imaged (0-600 Hz), no matching of the solute concentration was performed, and the Tsat was varied during the acquisition. Although CEST-MRF can vary several acquisition parameters simultaneously at each iteration, we have chosen to focus this report on schedules that vary only the saturation power, due to the previously established efficiency of quantitative mapping with varied powers,34 and to simplify the multi-parameter dependencies involved. The tools used throughout this work (DPloss, EDloss, and the Monte Carlo noise-based simulations) could be useful for future optimizations, as they are not dependent on the number of varied parameters at each iteration. Recently, a quantitative exchange rate and concentration mapping method was suggested, which fits the signals of a steady state CEST repeated experiment to the Bloch-McConnell equations using a nonlinear least-square technique.44 The authors reported that a CEST-MRF matching using the same parameters had inferior results. This can possibly be explained by the specific set of acquisition parameters used (Tsat < 800 ms, saturation power <1.2 μT) that clearly deviated from the optimal sets found here.

The dot product matching metric is commonly used in MRF experiments.42,43 However, several studies have recently used the Euclidean distance metric.57,58 Its utilization in this work, combined with the normalization by the M0 signal, has demonstrated several important advantages. The optimal saturation powers for the Euclidean distance metric were approximately 2 times smaller than their equivalents for the dot product metric, in both scenarios “A” and “B”, and approximately 10% smaller for scenario “C” (Figures 1 and 2). This may reduce the specific absorption rate (SAR) level, an essential element for clinical translation. In both numerical simulations (Figure 5) and phantom studies (Figures 6 and 7), it was shown that the Euclidean distance may reduce the matching errors, as well as reduce the schedule length (11 instead of 30 iterations) and hence scan time. We assume that the improved discrimination ability, demonstrated in both the numerical simulation (Figure 5) and in the phantom study (Figure 8), mostly at image acquisition number Nt = 11, arises from the added information provided by the relatively low saturation power at this iteration (Supporting Information Figure S1B), which broadens the range of saturation powers used up until that iteration. In the phantom study conducted here, a single long TR (15s) was used following the added unsaturated reference scan, to allow convenient comparison with dot product matching based on the same acquired images. However, a much shorter TR value can be used following this iteration, as the signal evolution is anyway simulated in the dictionary. The improved results gained by the Euclidean distance metric can potentially be explained by examining the morphology of the MRF trajectories (Figures 3 and 4), showing that the discriminative information seems to be mostly manifested as signal intensity variations. As the Euclidean distance metric is more sensitive to such information than to pattern variations58 it seems to be more suitable for CEST-MRF than the dot product metric. Moreover, the normalization by the unsaturated M0 signal prevents the loss of some amplitude-related information, as caused by the 2-norm normalization of the entire acquired trajectory. To allow the flexibility of using both metrics, we suggest acquiring an M0 scan at the beginning of the CEST-MRF schedule.

Interestingly, simultaneous fitting of QUESP data for the determination of exchangeable proton concentration and the exchange rate yielded considerable errors in the solute concentration (Table 2). The total RMSE for the solute concentration was 16.4 mM for QUESP, compared to 8.03 mM for Euclidean distance-based CEST-MRF with 30 acquisition iterations. This highlights the added value of fingerprinting as a multi-parameter matching method.

Another practical consideration demonstrated by the results obtained here is that the discrimination ability of CEST-MRF decreases with decreasing T2 and increasing MT proton volume fraction. This is demonstrated in Figure 2 where the optimal discrimination is decreased (increased loss, min EDloss = 0.911) in scenario B with short water T2 compared to scenario C (min EDloss = 0.824) with longer relaxation times. Similarly, the introduction of the semi-solid proton pool in scenario A leads to a further loss of exchange rate discrimination (min EDloss = 0.950) compared to scenario B with no MT pool. The reduced discrimination observed for shorter T2 and larger proton MT volume fraction can be overcome with higher SNR, so that small signal trajectory differences can still be distinguished, or larger ranges of chemical exchange rate. This suggests that CEST-MRF will have better performance for exogenous CEST agents with fast chemical exchange rates, compared to endogenous amide-proton imaging, and that longer T2 relaxation times at lower field strengths may be advantageous.

The simulated in vivo scenario included the contribution of 3 pools: amide, semi-solids, and water. However, in some tissues, there could also be an additional contribution by the amine pools, manifested at 2 ppm (commonly attributed to creatine) and at 3 ppm (mostly attributed to glutamate). Although the exchange rates for these pools are in the intermediate to fast regime, it was previously shown that they may have an effect on the amide CEST signal.59,60 To investigate the potential MRF-matching inaccuracies stemming from neglecting the amine pools, we have simulated 4-pool in vivo trajectories with various amine concentrations and matched them to the 3-pool in vivo dictionary for the optimized acquisition parameters found for the 3-pool in vivo scenario (Supporting Information Table S1). The maximal amide proton exchange rate and volume fraction RMSE due to the 2-ppm amine pool (kex = 500 Hz) were 9.33 Hz and 0.089%, respectively, for the dot product optimized protocol, and 4.77 Hz and 0.039% for the Euclidean distance optimized protocol. The maximal RMSE errors due to the 3-ppm amine pool (kex = 5000 Hz) were 23.92 Hz and 0.138% for the dot product optimized protocol and 10.44 Hz and 0.06% for the Euclidean distance optimized protocol. This highlights the advantage of using the Euclidean distance-based optimized parameters, which resulted in significantly lower saturation powers (maximum 1.6 μT, compared to 3.4 μT for the dot product-based optimization) and, therefore, is less influenced by the amine pools. The effect of the amine pool on the MRF-trajectories is further visualized in Supporting Information Figure S2, where for fixed amide exchange parameters, varying the amine pool concentration has almost no effect on the signal trajectory. Note that the influence of the amine pool is relatively subtle for typical in vivo amide proton properties and that most of the errors occur for very slow (<30 Hz) exchange rates (Supporting Information Figure S3). Therefore, neglect of the fast exchanging amine proton pool is expected to result in minimal error in the amide proton exchange parameters, in particular for the Euclidian distance-based matching metric. In the future, the contribution of the amine pools could potentially be accounted for by sampling saturation frequency offsets between 2 and 3 ppm in the acquisition schedule and including the amine pool in the matching dictionary.

Although the RMSE Monte Carlo-based noise measure (Figure 5B-C) were generally able to predict the quantitative experimental results (Figure 8), some discrepancies were observed. These differences are mostly associated with the fact that the Monte Carlo simulations were performed for all dictionary entries throughout the entire range of parameters, whereas the experimental evaluation had a total of 9 vials, corresponding to 9 specific combinations of parameters. The noise level added to the Monte Carlo simulation (25 dB) was in good agreement with the actual noise measured from the 9 vials (23.8 ±1.93 dB). Since no image-averaging is performed in CEST-MRF, the noise level is slightly higher than typical CEST contrast.61 It should be noted that a Gaussian, rather than a Rician noise was used, due to the sufficiently high SNR levels.62,63

The usefulness of the DPloss metric was previously demonstrated in optimizing the varied schedule parameters (FA and TR) for water-pool MRF EPI sequences.54 However, Sommer et al,55 have recently reported that dot product-based metrics are not suitable for schedule truncation studies in classical water pool MRF, and demonstrated the efficiency of Monte Carlo noise-based simulations for this task. Conversely, this study had yielded a generally good agreement between the DPloss and the Monte Carlo-related measures (Figure 5A,B). A possible explanation may be the difference between the exact definitions of the loss. While a global maximum dot product-based metric or a sum of dot product correlations in only a small local area of the entire dictionary was used by Sommer et al,55 a full consideration of the entire dictionary dot product values was performed in DPloss, as defined in this work. Moreover, while conventional T1/T2 MRF is prone to under sampling noise,62 which are not accounted for in the dot product-based loss measures, CEST-MRF is much less affected by such contaminations since a fully k-space sampled EPI sequence was employed with a relatively high SNR observed in the raw images.

The optimization of the acquisition parameters was performed sequentially so that 2 parameters were varied at each step. To verify that similar results are obtained for a different parameter optimization order, we have repeated the saturation power and Tsat optimization (originally optimized in the first step), while using the optimized values found for all other parameters. As can be seen in Supporting Information Figure S4 and Table S2, the resulting surface plots and the optimal parameters found were very similar to those obtained using the original optimization order (Figures 1 and 2A-C). This strengthens the validity of the optimal set found. However, due to the very large multi-parameter space involved in CEST-MRF, it is possible that we have reached a locally optimized solution and some better global solution exists. Future work is planned for incorporating machine learning-based algorithms to accelerate the pursuit of such globally optimized acquisition schedules.64,65

Various efforts were previously taken to optimize the sequence of acquisition schedule parameters for T1/T2 water pool MRF (FA and TR).54,55,66 The scope of this work was limited to a fundamental understanding of the limitations in CEST-MRF acquisition schedule parameters range, and to reducing the number of schedule iterations and thus used a fixed schedule with the range of the saturation power scaled. Nevertheless, the sequence of saturation powers used in a CEST-MRF experiment could be further optimized using the above-mentioned published methods combined with the fast dictionary generation software and the discrimination metrics presented here.

5 ∣. CONCLUSION

CEST-MRF holds unique challenges for the optimization of the image acquisition parameters stemming from the long saturation times required to generate significant CEST contrast. Here, we found optimal acquisition parameters that represent a compromise between generating large amplitude differences in the signal trajectory and non-steady state conditions with unique trajectory patterns. The Euclidean distance-based matching of signal trajectories may simultaneously improve the discrimination ability and reduce the scan time. For obtaining the most accurate CEST-MRF exchange parameter maps, it is critical to optimize the acquisition parameters for the specific application using numerical simulations of the parameter discrimination.

Supplementary Material

FIGURE S1 A, Schematic of the CEST-MRF pulse sequence with the parameters optimized throughout this work. Each iteration comprises a continuous saturation block where a pseudo-random saturation power B1[n] is used at a specific saturation offset for a fixed saturation duration (Tsat). Next, standard imaging and relaxation blocks are performed, with a fixed flip angle (FA), TE, and TR. B, The baseline saturation powers used in42

FIGURE S2 A comparison between CEST-MRF trajectories in the presence of various concentrations of amine exchangeable protons. In all cases, the amide exchange rate and volume fractions were set to 40 Hz and 0.63% respectively. The rest of the pool parameters were as depicted in Table 1 scenario A (for amide, MT, and water), and Supporting Information Table S1 (for amine proton concentration of 0 - 40 mM). A-B, 2-norm normalized trajectories for the protocol with parameters optimized for dot product matching in the presence of 2-ppm and 3-ppm amine, respectively. C-D, M0 normalized trajectories for the protocol with parameters optimized for Euclidean distance matching in the presence of 2-ppm and 3-ppm amine, respectively

FIGURE S3 Visualizing the error distribution for amide proton volume fraction matching in the presence of a 3-ppm amine pool. The Euclidean distance optimized protocol was utilized, and the amine proton concentration was set to 20 mM. The rest of the simulated parameters are depicted in Supporting Information Table S1. The entirely red squares represent dictionary entries that were not properly matched due to the amine pool

FIGURE S4 Dependence of the dot product (A-C) and Euclidean distance (D-F) loss on the saturation power and time (Tsat) parameters, while using the optimized parameter set found for FA, TE, and saturation frequency offset. The TR was fixed to 4 s instead of 8 s for practical considerations. The left, center, and right column correspond to chemical exchange scenarios A, B, and C, respectively. The z-axis represents the DPloss (A-C) or EDloss (D-F), which is color coded from blue to yellow. The optimal combination of saturation power and Tsat for each case is given in the surface plot

TABLE S1 Evaluation of the amine-pool effect on the amide MRF discrimination ability. The entire 570 trajectories of the in-vivo scenario A (see Table 1) were re-generated, with the addition of either a 2-ppm or a 3-ppm amine pool contribution. The simulated amine parameters were T1a = 1.45 s, T2a = 10 ms, kaw = 500 Hz59,60 (2-ppm)/5000 Hz59,60 (3-ppm), and amine proton concentrations of 10, 20, and 40 mM. The trajectories were simulated for the optimized protocol parameters found for the Dot product metric (Figure 1, left column) as well as for the Euclidean distance metric (Figure 2, left column) with the TR set to 4 s for practical reasons. The RMSE of matching the resulting trajectories with the 3-pool (no amine) reference dictionaries were calculated and are presented below

TABLE S2 The resulting saturation power and time (Tsat) values obtained for different orders of parameter optimization

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by an National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Numbers: R01CA203873, P41-RR14075.

Funding information

National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Numbers: R01CA203873, P41-RR14075.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Van Zijl PCM, Yadav Nirbhay N. Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST): what is in a name and what isn’t? Magn Reson Med. 2011;65:927–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward KM, Balaban RS. Determination of pH using water protons and chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST). Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:799–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaiss M, Bachert P. Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) and MR Z-spectroscopy in vivo: a review of theoretical approaches and methods. Phys Med Biol. 2013;58:R221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu G, Song X, Chan KW, McMahon MT. Nuts and bolts of chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI. NMR Biomed. 2013;26:810–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou J, Tryggestad E, Wen Z, et al. Differentiation between glioma and radiation necrosis using molecular magnetic resonance imaging of endogenous proteins and peptides. Nat Med. 2011;17:130–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones Craig K, Schlosser Michael J, et al. Amide proton transfer imaging of human brain tumors at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou J, Blakeley JO, Hua J, et al. Practical data acquisition method for human brain tumor amide proton transfer (APT) imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:842–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun PZ, Cheung JS, Wang E, Lo EH. Association between pH-weighted endogenous amide proton chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI and tissue lactic acidosis during acute ischemic stroke. J Cerebral Blood Flow Metabolism. 2011;31: 1743–1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou J, Zijl PCM. Defining an acidosis-based ischemic penumbra from pH-weighted MRI. Trans Stroke Res. 2012;3:76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeBrosse C, Nanga RPR, Wilson N, et al. Muscle oxidative phosphorylation quantitation using creatine chemical exchange saturation transfer (CrCEST). MRI Mitochondrial Disorders. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e88207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh A, Haris M, Cai K, et al. Chemical exchange saturation transfer magnetic resonance imaging of human knee cartilage at 3 T and 7 T. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68:588–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Müller-Lutz A, Schleich C, Pentang G, et al. Age-dependency of glycosaminoglycan content in lumbar discs: a 3t gagcEST study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;42:1517–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bagga P, Pickup S, Crescenzi R, et al. In vivo GluCEST MRI: reproducibility, background contribution and source of glutamate changes in the MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease. Sci Rep. 2018;8:2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai K, Haris M, Singh A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of glutamate. Nat Med. 2012;18:302–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis KA, Nanga RPR, Das S, et al. Glutamate imaging (GluCEST) lateralizes epileptic foci in nonlesional temporal lobe epilepsy. Sci Trans Med. 2015;7:309ra161–309ra161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pépin J, Francelle L, Sauvage M-A, et al. In vivo imaging of brain glutamate defects in a knock-in mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Neuroimage. 2016;139:53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crescenzi R, DeBrosse C, Nanga RPR, et al. In vivo measurement of glutamate loss is associated with synapse loss in a mouse model of tauopathy. Neuroimage. 2014;101:185–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crescenzi R, DeBrosse C, Nanga RPR, et al. Longitudinal imaging reveals subhippocampal dynamics in glutamate levels associated with histopathologic events in a mouse model of tauopathy and healthy mice. Hippocampus. 2017;27:285–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang S, Merritt M, Woessner DE, Lenkinski RE, Sherry AD. PARACEST agents: modulating MRI contrast via water proton exchange. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:783–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aime S, Barge A, Delli CD, et al. Paramagnetic lanthanide (III) complexes as pH-sensitive chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) contrast agents for MRI applications. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:639–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu Y, Zhang S, Soesbe TC, et al. pH imaging of mouse kidneys in vivo using a frequency-dependent paraCEST agent. Magn Reson Med. 2016;75:2432–2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terreno E, Cabella C, Carrera C, et al. From spherical to osmotically shrunken paramagnetic liposomes: an improved generation of LIPOCEST MRI agents with highly shifted water protons. Angewandte Chemie. 2007;119:984–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Longo DL, Sun PZ, Consolino L, Michelotti FC, Uggeri F, Aime S. A general MRI-CEST ratiometric approach for pH imaging: demonstration of in vivo pH mapping with iobitridol. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:14333–14336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vinogradov E, Sherry AD, Lenkinski RE. CEST: from basic principles to applications, challenges and opportunities. J Magn Reson. 2013;229:155–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones KM, Pollard AC, Pagel MD. Clinical applications of chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2018;47:11–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaiss M, Windschuh J, Paech D, et al. Relaxation-compensated CEST-MRI of the human brain at 7 T: unbiased insight into NOE and amide signal changes in human glioblastoma. Neuroimage. 2015;112:180–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zijl PCM, Lam WW, Xu J. Knutsson L, Stanisz GJ. Magnetization transfer contrast and chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI. Features and analysis of the field-dependent saturation spectrum. Neuroimage. 2018;168:222–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu J, Zaiss M, Zu Z, et al. On the origins of chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) contrast in tumors at 9.4 T. NMR Biomed. 2014;27:406–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun PZ, Murata Y, Lu J, Wang X, Lo EH, Sorensen AG. Relaxation-compensated fast multislice amide proton transfer (APT) imaging of acute ischemic stroke. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:1175–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khlebnikov V, Polders D, Hendrikse J, et al. Amide proton transfer (APT) imaging of brain tumors at 7 T: the role of tissue water T1-relaxation properties. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77:1525–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zu Z Towards the complex dependence of MTRasym on T1w in amide proton transfer (APT) imaging. NMR Biomed. 2018;31:e3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ji Y, Zhou IY, Qiu B, Sun PZ. Progress toward quantitative in vivo chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI. Israel J Chem. 2017;57:809–824. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMahon MT, Gilad AA, Zhou J, Sun PZ, Bulte JWM, Zijl PCM. Quantifying exchange rates in chemical exchange saturation transfer agents using the saturation time and saturation power dependencies of the magnetization transfer effect on the magnetic resonance imaging signal (QUEST and QUESP): pH calibration for poly-L-lysine and a starburst dendrimer. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:836–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zaiss M, Angelovski G, Demetriou E, McMahon MT, Golay X, Scheffler K. QUESP and QUEST revisited–fast and accurate quantitative CEST experiments. Magn Reson Med. 2018;79:1708–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Demetriou E, Tachrount M, Zaiss M, Shmueli K, Golay X. PRO-QUEST: a rapid assessment method based on progressive saturation for quantifying exchange rates using saturation times in CEST. Magn Reson Med. 2018;80:1638–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu R, Xiao G, Zhou IY, Ran C, Sun PZ. Quantitative chemical exchange saturation transfer (qCEST) MRI–omega plot analysis of RF-spillover-corrected inverse CEST ratio asymmetry for simultaneous determination of labile proton ratio and exchange rate. NMR Biomed. 2015;28:376–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hua J, Jones CK, Blakeley J, Smith SA, Van Zijl PCM, Zhou J. Quantitative description of the asymmetry in magnetization transfer effects around the water resonance in the human brain. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:786–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zaiss M, Schmitt B, Bachert P. Quantitative separation of CEST effect from magnetization transfer and spillover effects by Lorentzianline-fit analysis of z-spectra. J Magn Reson. 2011;211:149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou IY, Wang E, Cheung JS, Zhang X, Fulci G, Sun PZ. Quantitative chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI of glioma using Image Downsampling Expedited Adaptive Least-squares (IDEAL) fitting. Sci Rep. 2017;7:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma D, Gulani V, Seiberlich N, et al. Magnetic resonance fingerprinting. Nature. 2013;495:187–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bipin MB, Coppo S, Frances MD, et al. Magnetic resonance fingerprinting: a technical review. Magn Reson Med. 2019;81:25–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen O, Huang S, McMahon MT, Rosen MS, Farrar CT. Rapid and quantitative chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging with magnetic resonance fingerprinting (MRF). Magn Reson Med. 2018;80:2449–2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou Z, Han P, Zhou B, et al. Chemical exchange saturation transfer fingerprinting for exchange rate quantification. Magn Reson Med. 2018;80:1352–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heo H-Y, Han Z, Jiang S, Schär M, Zijl PCM, Zhou J. Quantifying amide proton exchange rate and concentration in chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging of the human brain. NeuroImage. 2019;189:202–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haris M, Nanga RPR, Singh A, et al. Exchange rates of creatine kinase metabolites: feasibility of imaging creatine by chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI. NMR Biomed. 2012;25:1305–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farrar CT, Buhrman JS, Liu G, et al. Establishing the lysine-rich protein CEST reporter gene as a CEST MR imaging detector for oncolytic virotherapy. Radiology. 2015;275:746–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gilad AA, Laarhoven HWM, McMahon MT, et al. Feasibility of concurrent dual contrast enhancement using CEST contrast agents and superparamagnetic iron oxide particles. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:970–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun PZ, Longo DL, Hu W, Xiao G, Wu R. Quantification of iopamidol multi-site chemical exchange properties for ratiometric chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging of pH. Phys Med Biol. 2014;59:4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Golub GH, Van Loan CF. Matrix computations; 3, Baltimore, MD: JHU Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morrison C, Mark HR. A model for magnetization transfer in tissues. Magn Reson Med. 1995;33:475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zaiss M, Zu Z, Xu J, et al. A combined analytical solution for chemical exchange saturation transfer and semi-solid magnetization transfer. NMR Biomed. 2015;28:217–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guennebaud G, Jacob B, et al. Eigen v3 http://eigen.tuxfamily.org 2010.

- 53.Dagum L, Menon R. OpenMP: an industry-standard API for shared-memory programming. Comput Sci Eng. 1998;46–55. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohen O, Rosen MS. Algorithm comparison for schedule optimization in MR fingerprinting. Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;41:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sommer K, Amthor T, Doneva M, Koken P, Meineke J, Börnert P. Towards predicting the encoding capability of MR fingerprinting sequences. Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;41:7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun PZ, Wang Y, Lu J. Sensitivity-enhanced chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI with least squares optimization of Carr Purcell Meiboom Gill multi-echo echo planar imaging. Contrast Media Molecular Imaging. 2014;9:177–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cline CC, Chen X, Mailhe B, et al. AIR-MRF: accelerated iterative reconstruction for magnetic resonance fingerprinting. Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;41:29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ma HT, Ye C, Wu J, et al. A preliminary study of DTI Fingerprinting on stroke analysis. in Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 2014 36th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Chicagod, IL: IEEE; 2014:2380–2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang X-Y, Wang F, Li H, et al. Accuracy in the quantification of chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) and relayed nuclear Overhauser enhancement (rNOE) saturation transfer effects. NMR Biomed. 2017;30:e3716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang X-Y, Wang F, Xu J, Gochberg DF, Gore JC, Zu Z. Increased CEST specificity for amide and fast-exchanging amine protons using exchange-dependent relaxation rate. NMR Biomed. 2018;31:e3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou J, Heo H-Y, Knutsson L, Zijl PCM, Jiang S. APT-weighted MRI: Techniques, current neuro applications, and challenging issues. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;50:347–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kara D, Fan M, Hamilton J, Griswold M, Seiberlich N, Brown R. Parameter map error due to normal noise and aliasing artifacts in MR fingerprinting. Magn Reson Med. 2019;81:3108–3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gudbjartsson H, Patz S. The Rician distribution of noisy MRI data. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:910–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu B, Liu J, Koonjoo N, Rosen B, Rosen MS. AUTOmated pulse SEQuence generation (AUTOSEQ) and neural network decoding for fast quantitative MR parameter measurement using continuous and simultaneous RF transmit and receive. in ISMRM Annual Meeting & Exhibition, 1090 Montreal, QC, Canada: International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cohen O MR Fingerprinting SChedule Optimization NEtwork (MRF-SCONE). In 27th Annual Meeting of ISMRM, Montreal, Canada, 2019. Abstract 4531. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao B, Haldar JP, Liao C, et al. Optimal experiment design for magnetic resonance fingerprinting: Cramer-Rao bound meets spin dynamics. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2018;38:844–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FIGURE S1 A, Schematic of the CEST-MRF pulse sequence with the parameters optimized throughout this work. Each iteration comprises a continuous saturation block where a pseudo-random saturation power B1[n] is used at a specific saturation offset for a fixed saturation duration (Tsat). Next, standard imaging and relaxation blocks are performed, with a fixed flip angle (FA), TE, and TR. B, The baseline saturation powers used in42

FIGURE S2 A comparison between CEST-MRF trajectories in the presence of various concentrations of amine exchangeable protons. In all cases, the amide exchange rate and volume fractions were set to 40 Hz and 0.63% respectively. The rest of the pool parameters were as depicted in Table 1 scenario A (for amide, MT, and water), and Supporting Information Table S1 (for amine proton concentration of 0 - 40 mM). A-B, 2-norm normalized trajectories for the protocol with parameters optimized for dot product matching in the presence of 2-ppm and 3-ppm amine, respectively. C-D, M0 normalized trajectories for the protocol with parameters optimized for Euclidean distance matching in the presence of 2-ppm and 3-ppm amine, respectively

FIGURE S3 Visualizing the error distribution for amide proton volume fraction matching in the presence of a 3-ppm amine pool. The Euclidean distance optimized protocol was utilized, and the amine proton concentration was set to 20 mM. The rest of the simulated parameters are depicted in Supporting Information Table S1. The entirely red squares represent dictionary entries that were not properly matched due to the amine pool

FIGURE S4 Dependence of the dot product (A-C) and Euclidean distance (D-F) loss on the saturation power and time (Tsat) parameters, while using the optimized parameter set found for FA, TE, and saturation frequency offset. The TR was fixed to 4 s instead of 8 s for practical considerations. The left, center, and right column correspond to chemical exchange scenarios A, B, and C, respectively. The z-axis represents the DPloss (A-C) or EDloss (D-F), which is color coded from blue to yellow. The optimal combination of saturation power and Tsat for each case is given in the surface plot

TABLE S1 Evaluation of the amine-pool effect on the amide MRF discrimination ability. The entire 570 trajectories of the in-vivo scenario A (see Table 1) were re-generated, with the addition of either a 2-ppm or a 3-ppm amine pool contribution. The simulated amine parameters were T1a = 1.45 s, T2a = 10 ms, kaw = 500 Hz59,60 (2-ppm)/5000 Hz59,60 (3-ppm), and amine proton concentrations of 10, 20, and 40 mM. The trajectories were simulated for the optimized protocol parameters found for the Dot product metric (Figure 1, left column) as well as for the Euclidean distance metric (Figure 2, left column) with the TR set to 4 s for practical reasons. The RMSE of matching the resulting trajectories with the 3-pool (no amine) reference dictionaries were calculated and are presented below

TABLE S2 The resulting saturation power and time (Tsat) values obtained for different orders of parameter optimization