Abstract

Adult day services (ADS) provide respite for dementia caregivers and directly reduce exposure to behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). This study examines the psycho-behavioral mechanism on how daily ADS use may benefit caregivers’ daily affect through its impact on the distress associated with BPSD stressor exposure. The sample consists of dementia caregivers (N = 173) who participated in an ADS intervention across 8 days. Multilevel structural equation modeling was conducted to examine the within- and between-person mediating effects of BPSD distress on the direct associations between daily ADS use and daily negative and positive affect. ADS days were associated with lower daily negative affect and higher daily positive affect; the significant within-person effect of ADS use on daily affect was mediated by daily BPSD distress. Findings highlight the association between daily ADS use and caregiver affective well-being. This understanding is important for designing respite and other interventions to help dementia caregivers manage the daily stress of caregiving.

Keywords: Dementia Family Caregiving, Adult Day Services, Respite, Caregiver Intervention, Daily Affect

Respite has garnered attention and support for its potential to address the most pressing needs of caregivers who provide care to a person with dementia (henceforth, care-recipient). Respite is generally defined as temporary, short-term help, or supervision provided to the care-recipient that enables caregivers to take a break. The benefits of respite are reflected in aging policy, as respite care is the dominant service strategy to support family caregivers in the United States under the aging and disability Medicaid home- and community-based services waiver program. Adult day services (ADS) are a form of respite that provide out-of-home care and structured activities to individuals with physical or cognitive impairments. ADS provide respite to caregivers and the use of ADS is associated with positive health-related (Liu, Kim, & Zarit, 2015), psychosocial (Liu, Kim, Almeida, & Zarit, 2015), and behavioral outcomes for care-recipients and caregivers (Ellen, Demaio, Lange, & Wilson, 2017). More immediate daily benefits of ADS use have been found in caregivers’ biological markers of stress, suggesting that regular use of ADS may contribute to a protective and restorative physiologic response to the demands of caregiving (Klein et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017; Zarit, Whetzel, et al., 2014). ADS use is also linked to caregivers’ improved affect and lower levels of anger (Zarit, Kim, Femia, Almeida, & Klein, 2014).

A major benefit of using ADS is that caregivers lower their exposure to care stressors, such as behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD; Zarit et al., 2011). BPSD are major sources of psychological distress for family caregivers, including agitation, unusual motor behavior, anxiety, excitement, irritability, depressive symptoms or behaviors, apathy, aggression, disinhibition, delusions, hallucinations, and changes in sleep or appetite (Cerejeira, Lagarto, & Mukaetova-Ladinska, 2012). These non-cognitive symptoms result in considerable emotional, social, and economic costs for caregivers (Gaugler, Yu, Krichbaum, & Wyman, 2009). Research has found that while some BPSD, such as agitation/aggression and irritability/lability may occur at low frequency, these behaviors have greater psychological impact on caregivers than other, more frequently occurring cognitive problems associated with dementia (Feast, Moniz-Cook, Stoner, Charlesworth, & Orrell, 2016; Matsumoto et al., 2007). A robust evidence base supports the idea that ADS are associated with better caregiver outcomes but it is not known if such benefits are primarily the result of providing caregivers with time away from the care-recipient or if positive gains are the result of lower distress associated with BPSD during respite.

The transactional theory of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) emphasizes the important role that appraisal or self-evaluation plays in how a person reacts, feels, and behaves in response to potentially distressing or disturbing circumstances (Lyons, Zarit, & Townsend, 2000). BPSD are not equally distressing and the occurrence of BPSD is not in itself stressful. Rather, research has documented substantial variability in how caregivers appraise BPSD (Fauth & Gibbons, 2014; Lawton, Kleban, Moss, Rovine, & Glicksman, 1989; Melo, Maroco, & de Mendonça, 2011; Teri et al., 1992). Caregivers build coping skills and resources to positively, negatively, or neutrally appraise and ascribe meaning to various BPSD that occur at varying frequencies (Lawton et al., 1989). While the association between ADS use and lower BPSD frequency has been established (Zarit et al., 2011), less work has explored how ADS use is associated with the distress that caregivers attribute to BPSD. The extension of this work is necessary in order to understand how respite, specifically ADS, is linked to caregiver distress. Consistent with the transactional theory, we focus on distress associated with BPSD, as it represents the key dimension for understanding caregiver differences in responses to BPSD. As such, reducing distress associated with BPSD (i.e., how stressful caregivers perceive BPSD) is a critical step in improving caregivers’ emotional well-being.

BPSD Distress as a Mediator of the Direct Association Between ADS Use and Daily Affect

It is critical to understand the mechanisms that are targeted by an intervention to bring about changes in behaviors and well-being (Mackinnon & Dwyer, 1993). Mediation analysis has been widely used to examine the causal mechanisms through which an intervention program works (Baron & Kenny, 1986; MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007). The concept of mediation suggests that the effectiveness of an intervention is at least partially transmitted through a mediator to the outcome variable. By revealing the elements that are essential to successful interventions, mediation analyses can help researchers identify specific ways to enhance effectiveness.

In examining mechanisms of how ADS use impacts caregivers’ daily affect two processes may be involved: a) within-person and b) between-person mediation of BPSD distress. At the within-person level, ADS use can have effects on caregivers’ daily affect by lowering BPSD distress on a given day when ADS was used. At the between-person level, caregivers who had greater intervention dosage (more ADS days) may have lower BPSD distress and improved average daily affect, compared to other caregivers who had less dosage (fewer ADS days).

The Current Study

The current study focused on BPSD distress as a potential mechanism that mediates the direct association between daily ADS use and daily affect. We examined how ADS use is linked to daily negative affect (NA) and positive affect (PA) by lowering the distress associated with BPSD. Examining both the within-person and between-person mediating effects of BPSD distress in the direct association between ADS use and daily affect is novel. We hypothesized that the BPSD distress will have a significant within-person mediation effect in the association between daily affect and daily ADS use (Hypothesis 1). We also hypothesized that BPSD distress have a significant between-person mediation effect in the association between daily affect and total number of ADS days (Hypothesis 2).

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited in the Daily Stress and Health (DaSH) study, which examines the effects of ADS use by family caregivers of a person with dementia on daily stressors and well-being (Zarit, Kim, et al., 2014). Ethics approval was obtained through The Pennsylvania State University institutional review board. Participants provided primary care to and lived in the same household as the care-recipient. ADS programs were identified in five separate geographical areas including Central New Jersey, the greater Philadelphia area, the greater Pittsburgh area, Northern Virginia, and Denver, Colorado. Meetings were held at each ADS program to explain the study. Partnering ADS programs received fliers for potential participants, which contained information about the study and the e-mail and telephone number of the study’s research coordinator. Family caregivers who contacted the research coordinator were informed about the study and subsequently screened for eligibility.

A total of 57 ADS programs provided participant referrals over a 3-year recruitment period. Of the original 241 individuals screened for eligibility, 173 caregivers participated in the study. In the initial screening process, 41 people (17%) were identified who were not eligible for the study. The most frequent reasons were not having eligible dementia diagnosis (n = 16), not living with the care-recipient (n = 5), and not using enough days of ADS (n = 11). Following the screening, 6 of the 200 eligible participants (3%) decided not to enroll in the study. Ten participants (5%) did not complete the initial in-home interview, and two persons (1%) only completed the initial interview but no daily interviews. Nine caregivers (4.5%) were eliminated because their daily interviews did not include both days their relative attended ADS and days their relative did not attend ADS. The resulting sample was 173 people (86.5% of eligible participants; Zarit, Kim, et al., 2014). Participants received $25 payment for their participation.

Procedures

An initial in-person interview was conducted during which the interviewer obtained signed consent, explained what the study involved, and gathered sociodemographic data and information about the care-recipient and caregiving situations. Following an initial in-person interview, participants completed daily phone interviews that assessed caregivers’ daily care-related stressors, non-care stressors, ADS use, and positive and negative affect in the evenings for 8 consecutive days. The Pennsylvania State University Survey Research Center conducted the daily phone interviews. Interviews ranged from 5 minutes to 1 hour and 19 minutes (M = 16.52, SD = 7.33).

Measures

Daily affect.

Daily affect was measured using 24 items from the Non-Specific Psychological Distress Scale (Kessler et al., 2002) and the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). During each evening interview, caregivers self-reported the frequency (5-point scale; 1 = none of the day to 5 = all day) for each of the items they experienced over the past day. To confirm the clear structure of negative and positive affective domains relevant to caregivers, we performed a factor analysis using the 24 items. We found that four items did not load well on either the negative or positive domains. For the current study, we used 11 items for NA and 9 items for PA with a total of 20 items, coded so that higher scores indicated higher levels of daily NA and PA (α = .88 for NA and α = .92 for PA). The intraclass correlation (ICC) coefficients were .66 for NA and .74 for PA.

BPSD distress.

Caregiver self-reports of psychological distress were measured using the Daily Record of Behavior (DRB; Fauth, Zarit, Femia, Hofer, & Stephens, 2006). The DRB had a modest internal reliability (α = .73); this is to be expected, however, because the occurrence of one behavior domain may actually decrease the occurrence of behaviors in other domains (Femia, Zarit, Stephens, & Greene, 2007). On each day, caregivers completed a 19-item version of the DRB that assessed the following 6 behavior domains (activity of daily living, restless behaviors, reality problems, mood problems, disruptive behaviors, and memory problems; Fauth et al., 2006; Femia et al., 2007). Caregivers were asked if the behavior had occurred (yes/no) within the past 24 hours, and if yes, how stressful the behavior was for them. The caregivers’ appraisal was rated along a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all stressful) to 5 (very stressful). In the absence of any behavior problems, the corresponding appraisal score was coded as missing. If the behavior occurred more than once during the time period, the appraisal was for the caregiver’s perception of the most stressful occurrence. This appraisal score was used to calculate caregiver distress in the analysis.

The previous 24-hour time period from the time of the telephone interview was divided into four periods: (1) waking to 9 a.m., (2) 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., (3) 4 p.m. to bedtime, and (4) overnight. The present study utilized a sum of BPSD distress scores from periods 1–3 (waking to bedtime) to measure caregivers’ total distress for each of the 8 days of the study. Because we sought to measure distress associated with behaviors that occur during the day, overnight BPSD distress was not included in the current study. The reliability using sum distress score was .82 in the morning phase, .86 in the daytime phase, and .84 in the evening phase. Further, the ICCs for BPSD distress were .59, .56, and .62 for the morning, daytime, and evening phase, respectively.

ADS.

Caregivers voluntarily used ADS on some of the 8 consecutive diary days; they provided active care on the rest of the days. We considered both within- and between-person effects of ADS use in the analysis. Thus, the within-person ADS use was dichotomized to show whether caregivers used ADS for the care-recipient on that day (1 = ADS day) or not (0 = non-ADS day). The between-person ADS use was computed as the total number of all ADS days during the 8-day study period.

Covariates.

Variables were selected as covariates in our model based on their demonstrated importance to caregiver outcomes. Covariates included: caregiver age (in years), gender (1 = female, 0 = male), relation to care-recipient (i.e., spouse, adult child, other relationship), and duration of care (self-reported number of months providing care). Older caregivers perceive their role as more difficult than younger caregivers, citing their own declining physical and emotional health, loneliness, and their own death as key issues (Greenwood, Pound, Brearley, & Smith, 2019). The gender of the caregiver has been found to influence the impact of the caregiving experience and caregiver burden (Etters, Goodall, & Harrison, 2008; Kim, Chang, Rose, & Kim, 2012). Relation to care-recipient, that is, whether the caregiving role is fulfilled by a spouse, adult offspring, other relative, or a friend, may hold different implications for caregiver outcomes (Pillemer & Suitor, 2006). For example, lower perceived burden has been found among female and male spouse caregivers, daughter caregivers, and mother caregivers (Juntunen et al., 2018). Finally, duration of care is of critical importance when understanding the caregiver stress process, particularly within dementia caregiving which can last for years. Gaugler and colleagues (2005), for example, found that duration of care had a strong, negative, and direct effect on time to nursing home placement.

Analytic Strategy

Demographics.

Preliminary analyses were conducted to show demographics of caregivers enrolled in the study. For descriptive purposes, we looked at caregivers’ demographics (e.g., education level and minority status) in addition to characteristics of the care-recipient (e.g., age, gender, and level of ADL impairment).

Hypotheses.

To test the hypotheses on the (within- and between-person) mediation effects of BPSD distress in the association between ADS use and daily affect, the within- and between-person models were fit simultaneously using the multilevel structural equation modeling (MSEM) approach (MacKinnon & Valente, 2014; Preacher, Zhang, & Zyphur, 2011). The MSEM approach has some advantages over the univariate multilevel models. First, it can efficiently accommodate more than one outcome in the model, where the covariation between daily NA and PA can be considered. Thus, the current study modeled daily NA and PA as outcomes simultaneously in one MSEM model, instead of fitting two separate univariate multilevel models. Further, the MSEM approach can substantially reduce estimation bias in the indirect effects (Muthén & Asparouhov, 2008), which was the primary focus of the current study.

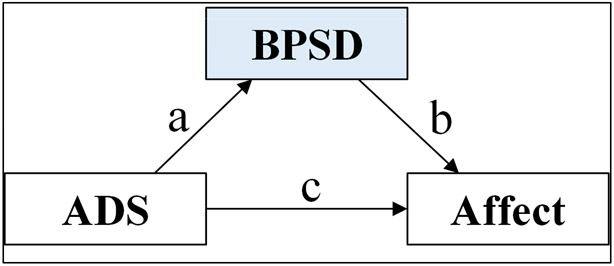

The mediation model examines whether daily ADS use and total ADS days influence BPSD distress, which in turn influences daily negative and positive affect. Thus, the mediator variable, BPSD distress, clarifies the nature of the association between ADS use and daily emotional well-being. Specifically, the mediation model tests if the indirect effect, which is the product of path coefficients a and b (Figure 1) at the within- and between-person levels, is significant. Further, The “within-person” indirect effect of ADS use via BPSD distress on affect was tested by fitting the structural model at the day level (i.e., the 1–1-1 model, in which the predictor, mediator, and outcome variables were measured at Level 1, the day level). The “between-person” indirect effect of ADS use via BPSD distress on affect was tested by fitting the structural model at the person level (i.e., the 2–1-1 model, in which the predictor, total number of ADS days was measured at Level 2, the person level; Preacher et al., 2010). Both the within-person and between-person structural models for hypothesis testing were fit in one general MSEM model using the Mplus package.

Figure 1.

Mediation model

ADS = adult day services. BPSD = behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.

Results

Caregivers completed 89% of all daily interviews. An average of 4.09 interviews (SD = 1.46) were on ADS days, and 3.77 interviews (SD = 1.43) were on non-ADS days. Descriptive statistics for the sample were represented in Table 1. Caregivers reported the BPSD frequency and BPSD distress across all 8 days of the study, and indicated higher BPSD frequency on non-ADS days (M = 19.39, SD = 24.32), compared to ADS days (M = 16.29, SD = 22.73). Likewise, the sum of BPSD distress was higher on non-ADS days (M = 18.36, SD = 20.93) than on ADS days (M = 14.28, SD = 19.91). To test the hypotheses that BPSD distress would mediate the link between ADS and affect (Figure 1), within- and between-person models were fit simultaneously. The model had acceptable overall fit based on three alternate fit indices, including Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). According to the rough guideline suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999), the indices should be over .95 for CFI, less than .06 for RMSEA, and less than .08 for SRMR. The current model showed .97 for CFI, .06 for RMSEA, and the SRMR values for within- and between-person models were .00 and .06, respectively. Figure 2 and Table 2 present the parameter estimates based on the hypothesized model.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Variable | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver characteristics | |||

| Age | 61.97 | 10.66 | 39–89 |

| Female, % | 86.71 | ||

| Spouse caregiver, % | 37.57 | ||

| Adult child caregiver, % | 58.38 | ||

| Other relationship types, % | 4.05 | ||

| White, % | 72.83 | ||

| Educationa | 4.46 | 1.20 | 1–6 |

| Duration of providing care (month) | 61.12 | 45.55 | 3–264 |

| Care-recipient characteristics | |||

| Age | 82.02 | 8.34 | 57–100 |

| Female, % | 60.12 | ||

| ADL impairmentb | 3.06 | 0.49 | 2–4 |

| Caregiver (daily) distress and affect | |||

| BPSD distressc | 15.49 | 19.23 | 1–144.63 |

| Negative affectd | 1.45 | 0.43 | 1–5 |

| Positive affecte | 3.02 | 0.83 | 1–5 |

Note. Participant N = 173; Participant-day observation N = 1,359.

ADL = activities of daily living. BPSD = behavioral problems and symptoms of dementia.

Rated on a 6-point scale from 1 (less than high school) to 6 (post-college degree).

Mean of 13 items rated from 1 (does not need help) to 4 (cannot do without help).

Sum of 19 items rated from 1 (not at all stressful) to 5 (very stressful) from time periods 1-3.

Mean of 11 items rated from 1 (none of the day) to 5 (all day).

Mean of 9 items rated from 1 (none of the day) to 5 (all day).

Figure 2.

Standard parameter estimates for the within-person (bottom) and between-person (top) structural models. Latent variables are represented by ovals, and measured variables are represented by rectangles. Significant estimates are shown in solid black and non-significant estimates (p > .05) are in dashed gray.

NA = negative affect. PA = positive affect. W = within-person effect. B = between-person effect. ADS = adult day services. BPSD = behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.

Table 2.

Multilevel Structural Equation Model for Caregivers’ Daily Affect

| Negative affect | Positive affect | |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) |

| Within-person level effect | ||

| ADS day → BPSD distress (aw) | −4.199 (0.952)*** | |

| BPSD distress (bw, cw) | 0.007 (0.001)*** | −0.005 (0.002)* |

| ADS day (dw, ew) | −0.002 (0.018) | 0.021 (0.030) |

| ADS day → BPSD distress → NA/PA (1-1-1 indirect) | −0.031 (0.009)*** | 0.021 (0.011)† |

| COV (NAw, PAw) | −0.061 (0.007)*** | |

| Between-person level effect | ||

| # of ADS days → BPSD distress (aB) | 0.382 (0.788) | |

| BPSD distress (bB, cB) | 0.012 (0.004)*** | −0.008 (0.003)* |

| # of ADS days (dB, eB) | −0.021 (0.017) | 0.094 (0.044)* |

| # of ADS days → BPSD distress → NA/PA (2-1-1 indirect) | 0.004 (0.009) | −0.003 (0.007) |

| COV (NAB, PAB) | −0.103 (0.020)*** | |

| Covariates | ||

| Age | 0.001 (0.004) | 0.002 (0.008) |

| Female | −0.063 (0.095) | 0.189 (0.191) |

| Spouse caregiver | 0.157 (0.090) | −0.553 (0.415) |

| Adult child caregiver | 0.157 (0.093) | −0.365 (0.425) |

| Duration of providing care | −0.001 (0.000) | 0.001 (0.001) |

| Intercept (NAB, PAB) | 1.262 (0.294)*** | 2.807 (0.734)*** |

| Intercept (BPSD distressB) | 15.942 (3.783)*** | |

Note. NA = negative affect. PA = positive affect. W = within-person effect. B = between-person effect. ADS = adult day services. BPSD = behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. COV = covariance.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

The within-person (1–1-1) structural model showed that Hypothesis 1 on the within-person mediation effect of BPSD distress in the association between ADS use and daily affect was supported. At the within-person level, daily NA and PA were negatively correlated (β = −0.061, p < .000). Higher daily BPSD distress was associated with higher daily NA (β = 0.007, p < .000) and lower daily PA (β = −0.005, p = .019); an ADS day was associated with lower daily BPSD distress (β = −4.199, p < .000). The direct associations between ADS day and daily NA and PA were not significant after controlling for daily BPSD distress. Central to Hypothesis 1, the estimated within-person indirect effect of ADS use (via BPSD distress) on daily NA was −0.031 (SE = 0.009, p < .001), and the estimated within-person indirect effect of ADS use (via BPSD distress) on daily PA was 0.021 (SE = 0.011, p = .054), suggesting that the significant within-person ADS effect on affect was mediated by the same (within-person) levels of BPSD distress.

The between-person (2–1-1) structural model showed that Hypothesis 2 on the between-person mediation of BPSD distress in the association between total number of ADS days and affect was not supported. At the between-person level, NA and PA were also negatively correlated (β = −0.103, p < .000). Higher BPSD distress was similarly associated with higher NA (β = 0.012, p = .001) and lower PA (β = −0.008, p = .021). Having more ADS days was associated with higher PA (β = 0.094, p = .032), after controlling for BPSD distress and other covariates. However, having more total ADS days was not related to NA (β = −0.021, p = .21) or BPSD distress (β = 0.382, p = .63). Central to Hypothesis 2, the estimated between-person indirect effect of ADS use (via BPSD distress) on affect was not significant. These findings suggested that total number of ADS days was not associated with overall levels of daily affect, and there was no evidence for the BPSD distress mediating total number of ADS days and overall levels of daily affect at the between-person level.

Discussion

With increasing public and policy support for respite, it is necessary for research to examine the nuances of respite services (such as ADS) and to understand how these services benefit caregivers beyond simply reducing care stressor exposure. In an effort to contribute to this broader mission, our study examined how ADS use is linked to daily NA and PA and distress associated with BPSD. In doing so, we tested the hypotheses that BPSD distress is a potential mediator of ADS and caregiver affect. Utilizing daily data, our study tested the within- and between-person effects of ADS on caregivers’ daily affect. Our results yield interesting disparities in between- and within-person effects when we examine BPSD distress as a potential mediator of ADS use and daily affect. These results are unique from previous DaSH findings, which have found associations between ADS use and caregivers’ biological markers of stress reactivity (Zarit, Whetzel, et al., 2014), depressive mood and anger (Leggett, Zarit, Kim, Almeida, & Klein, 2014). Our findings pose new views on how ADS can facilitate caregivers’ coping with cognitive and behavioral impairment.

At the within-person level (Hypothesis 1), our findings indicate that an ADS day was related to lower daily BPSD distress. These findings build on previous research that has focused on ADS achieving its immediate goal of lowering exposure to care stressors (e.g., exposure to BPSD; Zarit et al., 2014; Zarit et al., 2011). While much research has supported the idea that ADS use is beneficial to caregiver well-being by reducing exposure to care stressors, less attention has been paid to ADS as it relates to caregivers’ appraisal of care stressors. Thus, a novel finding of our study came from testing the hypothesis that the association between ADS use and daily affect is mediated by BPSD distress. Our results found that the within-person ADS effect on daily affect was mediated by lower levels of daily BPSD distress, which may indicate “immediate” (day-to-day) association between ADS use on how caregivers perceive BPSD. Although the between-person analyses did not show evidence of mediation between total ADS days and affect (Hypothesis 2), there was a direct effect on number of ADS days and higher PA. These findings suggest that immediate daily effects of respite may differ in some ways from cumulative effects of amount of respite use. Given that Hypothesis 2 was not supported, further study of potentially mediating factors is warranted, some potential mediators may be overall care stress (not specific to BPSD), or non-care stress.

These findings have an important implication for the broader science of interventions for dementia caregivers, specifically in the context of care-recipients who display heightened BPSD. Most psychoeducational interventions have included training procedures to improve management of BPSD and/or to lower negative attributions and other sources of distress, but benefits are often modest and data are often not presented on implementation of strategies by caregivers (Zarit & Femia, 2008; Zarit, 2018). Indeed, some caregivers struggle to implement even relatively simple behavioral management approaches, as these approaches require heightened resources and skills that not all caregivers may have. By contrast, ADS and other forms of respite provide a direct approach to lowering the amount of daily BPSD distress, which we found was associated with higher PA and lower NA. Caregivers have long expressed a need for high quality, accessible respite that provides a break from caregiving, reduces daily stress, and gives them time for other activities (Oliveira, Zarit, & Orrell, in press). Rather than placing responsibility on caregivers to manage BPSD through behavioral management approaches, respite enables them to take care of their own needs. Respite can also be a gateway to other interventions that help caregivers address other issues around their role and responsibilities (e.g., Gitlin, Reever, Dennis, Mathieu, & Hauck, 2006).

The current study builds on respite research that has explored the broader benefits of ADS, including decreased time spent providing care, worry, strain, and overload (Gaugler et al., 2003a, 2003b). Most respite research draws on retrospective self-reports of caregivers, which indicates that ADS can have a positive impact when used regularly over the course of time (Fields, Anderson, & Dabelko-Schoeny, 2014). Our findings, however, use daily data to build more nuanced evidence linking ADS use to caregivers’ daily affect. We found that on ADS days, caregivers’ had lower BPSD distress, which is associated with better daily affect (lower NA and higher PA). Greater use of ADS was related to higher average daily PA for caregivers, but not NA. It may be that the amount of ADS received may give caregivers more opportunity to engage in enjoyable activities or just provide relief from being on-call to monitor and respond to BPSD. While previous work has examined stressful and positive family caregiving experiences as predictors of caregivers’ patterns of PA and NA, our work suggests that respite may play a role in patterns of PA (Robertson, Zarit, Duncan, Rovine, & Femia, 2007). These results align with previous findings from the DaSH study that have demonstrated health benefits over time associated with amount of ADS use (Liu et al., 2015).

Limitations and Future Directions

This study should be viewed within the context of several limitations. First, our sample was limited to only caregivers who lived with their care-recipient. In reality, many individuals who do not live with the care-recipient (e.g., family members and friends) may contribute to the care, and surveying only one caregiver does not account for the larger social support network outside of the care-recipient/caregiver dyad. Future work should expand inquiry beyond the primary caregiver, and address caregiving issues at the family level. Second, while the daily design is particularly useful for understanding daily outcomes, this approach provides only one out of several possible pathways/mechanisms through which the variables may be related and it is possible that unobserved variables may account for these associations. Therefore, causal effects cannot be, nor are they intended to be, determined in the absence of multiple waves of observations. Longitudinal data are necessary to make such inferences. Third, we focused on BPSD distress, not BPSD frequency, based on the central role of appraisals in stress theory as leading to negative emotions. We recognize this approach may present issues of multicollinearity between BPSD frequency and distress (that is, BPSD must occur in order to be appraised as distressful or not). In the current sample, the sum score of BPSD distress was substantially correlated (r = .96, p < .001) with the frequency of BPSD. To avoid problems of multicollinearity, we ran an alternative model by controlling for the BPSD frequency count as a between-person covariate. This model showed that the major findings with regard to the indirect effect of ADS use remained consistent with the original model, but the model fit got much worse based on all major model fit indices (i.e., Chi-square, RMSEA, CFI, SRMR, and AIC/BIC). Thus, while BPSD frequency and BPSD distress are inherently related, our approach to focusing on BPSD distress is warranted both statistically and conceptually. Despite these limitations, this study makes significant contributions to the dementia caregiving literature by highlighting the association between ADS and daily affect. Assessment of the more immediate benefits of respite strengthens the evidence-base of respite for family caregivers and help guide federal policy efforts aimed at supporting family caregivers, such as the National Family Caregiver Support Program.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Aging at the National Institute of Health (R01 AG031758), Daily Stress and Health Study.

Footnotes

The ideas and data from this manuscript have not previously been disseminated.

References

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerejeira J, Lagarto L, & Mukaetova-Ladinska EB (2012). Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia. Frontiers in Neurology, 3 10.3389/fneur.2012.00073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellen ME, Demaio P, Lange A, & Wilson MG (2017). Adult Day Center Programs and Their Associated Outcomes on Clients, Caregivers, and the Health System: A Scoping Review. The Gerontologist, 57(6), e85–e94. 10.1093/geront/gnw165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etters L, Goodall D, & Harrison BE (2008). Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: A review of the literature. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 20(8), 423–428. 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00342.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauth EB, & Gibbons A (2014). Which behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia are the most problematic? Variability by prevalence, intensity, distress ratings, and associations with caregiver depressive symptoms. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(3), 263–271. 10.1002/gps.4002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauth EB, Zarit SH, Femia EE, Hofer SM, & Stephens MAP (2006). Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and caregivers’ stress appraisals: Intra-individual stability and change over short-term observations. Aging & Mental Health, 10(6), 563–573. 10.1080/13607860600638107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feast A, Moniz-Cook E, Stoner C, Charlesworth G, & Orrell M (2016). A systematic review of the relationship between behavioral and psychological symptoms (BPSD) and caregiver well-being. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(11), 1761–1774. 10.1017/S1041610216000922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Femia EE, Zarit SH, Stephens MAP, & Greene R (2007). Impact of Adult Day Services on Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia. The Gerontologist, 47(6), 775–788. 10.1093/geront/47.6.775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields NL, Anderson KA, & Dabelko-Schoeny H (2014). The Effectiveness of Adult Day Services for Older Adults: A Review of the Literature From 2000 to 2011. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 33(2), 130–163. 10.1177/0733464812443308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Jarrott SE, Zarit SH, Stephens MAP, Townsend A, & Greene R (2003). Respite for dementia caregivers: The effects of adult day service use on caregiving hours and care demands. INTERNATIONAL PSYCHOGERIATRICS, 15(1), 37–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler Joseph E., Jarrott SE, Zarit SH, Stephens M-AP, Townsend A, & Greene R (2003). Adult day service use and reductions in caregiving hours: Effects on stress and psychological well-being for dementia caregivers. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(1), 55–62. 10.1002/gps.772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler Joseph E., Yu F, Krichbaum K, & Wyman JF (2009). Predictors of Nursing Home Admission for Persons with Dementia: Medical Care, 47(2), 191–198. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818457ce [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Reever K, Dennis MP, Mathieu E, & Hauck WW (2006). Enhancing quality of life of families who use adult day services: Short- and long-term effects of the adult day services plus program. The Gerontologist, 46(5), 630–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood N, Pound C, Brearley S, & Smith R (2019). A qualitative study of older informal carers’ experiences and perceptions of their caring role. Maturitas, 124, 1–7. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juntunen K, Salminen A-L, Törmäkangas T, Tillman P, Leinonen K, & Nikander R (2018). Perceived burden among spouse, adult child, and parent caregivers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74(10), 2340–2350. 10.1111/jan.13733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Chang M, Rose K, & Kim S (2012). Predictors of caregiver burden in caregivers of individuals with dementia. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(4), 846–855. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05787.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein LC, Kim K, Almeida DM, Femia EE, Rovine MJ, & Zarit SH (2014). Anticipating an Easier Day: Effects of Adult Day Services on Daily Cortisol and Stress. The Gerontologist. 10.1093/geront/gnu060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Kleban MH, Moss M, Rovine M, & Glicksman A (1989). Measuring Caregiving Appraisal. Journal of Gerontology, 44(3), P61–P71. 10.1093/geronj/44.3.P61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RSL, & Folkman S (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Leggett AN, Zarit SH, Kim K, Almeida DM, & Klein LC (2014). Depressive Mood, Anger, and Daily Cortisol of Caregivers on High- and Low-Stress Days. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, gbu070 10.1093/geronb/gbu070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Kim K, & Zarit SH (2015). Health Trajectories of Family Caregivers: Associations With Care Transitions and Adult Day Service Use. Journal of Aging and Health, 27(4), 686–710. 10.1177/0898264314555319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Granger DA, Kim K, Klein LC, Almeida DM, & Zarit SH (2017). Diurnal salivary alpha-amylase dynamics among dementia family caregivers. Health Psychology, 36(2), 160–168. 10.1037/hea0000430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Kim K, Almeida DM, & Zarit SH (2015). Daily fluctuation in negative affect for family caregivers of individuals with dementia. Health Psychology, 34(7), 729–740. 10.1037/hea0000175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons KS, Zarit SH, & Townsend AL (2000). Families and formal service usage: Stability and change in patterns of interface. Aging & Mental Health, 4(3), 234–243. 10.1080/13607860050128256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon DP, & Dwyer JH (1993). Estimating Mediated Effects in Prevention Studies. Evaluation Review, 17(2), 144–158. 10.1177/0193841X9301700202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, & Fritz MS (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 593–614. 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, & Valente MJ (2014). Mediation from Multilevel to Structural Equation Modeling. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 65(2–3), 198–204. 10.1159/000362505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto N, Ikeda M, Fukuhara R, Shinagawa S, Ishikawa T, Mori T, … Tanabe H (2007). Caregiver burden associated with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in elderly people in the local community. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 23(4), 219–224. 10.1159/000099472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo G, Maroco J, & de Mendonça A (2011). Influence of personality on caregiver’s burden, depression and distress related to the BPSD. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(12), 1275–1282. 10.1002/gps.2677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, & Suitor JJ (2006). Making Choices: A Within-Family Study of Caregiver Selection. The Gerontologist, 46(4), 439–448. 10.1093/geront/46.4.439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Zhang Z, & Zyphur MJ (2011). Alternative Methods for Assessing Mediation in Multilevel Data: The Advantages of Multilevel SEM. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 18(2), 161–182. 10.1080/10705511.2011.557329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Zyphur MJ, & Zhang Z (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 209–233. 10.1037/a0020141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson SM, Zarit SH, Duncan LG, Rovine MJ, & Femia EE (2007, January 1). Family Caregivers’ Patterns of Positive and Negative Affect*. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00436.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teri L, Truax P, Logsdon R, Uomoto J, Zarit S, & Vitaliano PP (1992). Assessment of behavioral problems in dementia: The Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist. Psychology and Aging, 7(4), 622–631. 10.1037/0882-7974.7.4.622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, & Femia EE (2008). A future for family care and dementia intervention research? Challenges and strategies. Aging & Mental Health, 12(1), 5–13. 10.1080/13607860701616317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH (2018). Past is prologue: How to advance caregiver interventions. Aging & Mental Health, 22(6), 717–722. 10.1080/13607863.2017.1328482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Kim K, Femia EE, Almeida DM, & Klein LC (2014). The Effects of Adult Day Services on Family Caregivers’ Daily Stress, Affect, and Health: Outcomes From the Daily Stress and Health (DaSH) Study. The Gerontologist, 54(4), 570–579. 10.1093/geront/gnt045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Kim K, Femia EE, Almeida DM, Savla J, & Molenaar PCM (2011). Effects of Adult Day Care on Daily Stress of Caregivers: A Within-Person Approach. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66B(5), 538–546. 10.1093/geronb/gbr030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Whetzel CA, Kim K, Femia EE, Almeida DM, Rovine MJ, & Klein LC (2014). Daily Stressors and Adult Day Service Use by Family Caregivers: Effects on Depressive Symptoms, Positive Mood and DHEA-S. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry : Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(12), 1592–1602. 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]