Abstract

To date, there have been no long-term longitudinal studies of continuity and change in narcissism. This study investigated rank-order consistency and mean-level changes in overall narcissism and three of its facets (leadership, vanity, entitlement) over a 23-year period spanning young adulthood (Mage=18; N = 486) to midlife (Mage=41; N = 237). We also investigated whether life experiences predicted changes in narcissism from young adulthood to midlife, and whether young adult narcissism predicted life experiences assessed in midlife. Narcissism and its facets showed strong rank-order consistency from age 18 to 41, with latent correlations ranging from .61 to .85. We found mean-level decreases in overall narcissism (d = −0.79) and all three facets, namely leadership (d = −0.67), vanity (d = −0.46), and entitlement (d = −0.82). Participants who were in supervisory positions showed smaller decreases in leadership, and participants who experienced more unstable relationships and who were physically healthier showed smaller decreases in vanity from young adulthood to middle age. Analyses of the long-term correlates of narcissism showed that young adults with higher narcissism and leadership levels were more likely to be in supervisory positions in middle age. Young adults with higher vanity levels had fewer children and were more likely to divorce by middle age. Together, the findings suggest that people tend to become less narcissistic from young adulthood to middle age, and the magnitude of this decline is related to the particular career and family pathways a person pursues during this stage of life.

Keywords: narcissism, mean-level changes, personality development, maturity principle, vanity

Older adults tend to view today’s youth as particularly self-focused and narcissistic (Trzesniewski & Donnellan, 2014). However, empirical research indicates that the youth of today are not more narcissistic than the youth of prior generations (Donnellan, Trzesniewski, & Robins, 2009; Wetzel et al., 2017). Instead, the misguided belief that today’s youth are particularly narcissistic may reflect a general tendency for people to become less narcissistic as they age (Roberts, Edmonds, & Grijalva, 2010), leading every generation of adults to view the youth of their day as highly narcissistic. Indeed, cross-sectional studies have consistently found a negative correlation between age and narcissism scores (Foster, Campbell, & Twenge, 2003; Hill & Roberts, 2012; Wetzel, Roberts, Fraley, & Brown, 2016). However, until now, no longitudinal study has tracked change in narcissism from young adulthood to midlife. In the current paper, we report the longest (23-year) longitudinal investigation of continuity and change in narcissism reported to date, using data from the Berkeley Longitudinal Study (Robins & Beer, 2001).

In addition to examining rank-order consistency and mean-level changes in narcissism from age 18 to 41, we also examine the degree to which narcissism assessed during the participants’ first year in college predicts their life experiences over the next 23 years, including positive and negative events, career success, relationship outcomes, and health. Further, we examine whether life experiences during this period are correlated with individual differences in change in narcissism from college to midlife.

Narcissism and its facets

Narcissism as a continuous personality trait encompasses a variety of characteristics including a grandiose self-concept, feelings of superiority, entitlement, exploitativeness, and a lack of empathy (Cain, Pincus, & Ansell, 2008). In the current study, we assessed narcissism using a modified form of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI; Raskin & Hall, 1979; Raskin & Terry, 1988), the most widely used narcissism measure. The NPI has multiple facets, but there is some disagreement about the exact nature and number of these facets (Ackerman et al., 2011; Corry, Merritt, Mrug, & Pamp, 2008; Wetzel et al., 2016; 2017). In the current study, we chose to use Wetzel et al.’s three NPI facets: entitlement, vanity, and leadership. Entitlement is the most interpersonally toxic facet and is associated with devaluing others, being disagreeable, and producing lower levels of relationship satisfaction. Vanity reflects the tendency to take excessive pride in one’s own appearance and achievements and the propensity to want to be the center of attention. It is associated with grandiose fantasies of success. Leadership is considered the most adaptive facet and is associated with a desire to lead, extraversion, global self-esteem, and goal persistence (Ackerman et al., 2011).

The facets that comprise narcissism have been shown in cross-sectional research to have different associations with age (Hill & Roberts, 2012). Thus, we also evaluated rank-order consistency and changes over time in the facets of narcissism to disentangle potentially divergent developmental trends at the facet level.

Theoretical Perspectives on Continuity and Change in Narcissism

Personality traits are relatively stable over time. For example, in the developmental period covered by our study, meta-analytic estimates of mean consistency across the Big Five and a number of other personality traits for a length of time similar to the one examined in the present longitudinal study was .41 (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000). At the same time, it is also widely accepted that reliable change in personality tends to occur over the life span (Donnellan, Hill, & Roberts, 2015). In particular, the Neo-Socioanalytic Model of personality development proposes that most individuals become more mature with age, especially during young adulthood. Maturity is defined in social terms and is reflected in the tendency for most people to become more agreeable, conscientious, and emotionally stable with age (Roberts, Wood, & Caspi, 2008). This conjecture has been supported by meta-analyses and longitudinal studies showing that people do become more conscientious, agreeable, and emotionally stable from young adulthood to middle age (Damian, Spengler, Sutu, & Roberts, 2018; Roberts, Walton, & Viechtbauer, 2006).

What does this mean in relation to narcissism? Arguably, narcissism is the antithesis of maturity, as it is characterized by grandiose attention seeking, self-centeredness, and fragile, inflated self-perceptions (Donnellan, Ackerman, & Wright, in press; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). Narcissism is most strongly correlated with high extraversion and low agreeableness with the latter being consistent with low maturity (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). And, although narcissism is not typically correlated with overall conscientiousness, it has been linked to lower self-control (Jones & Paulhus, 2011; Vazire & Funder, 2006). Therefore, to the extent that narcissism entails lower agreeableness and lower aspects of conscientiousness, we would expect narcissism to decrease (H1). At the facet level, we predict that there will be decreases in the more maladaptive facets of narcissism that are associated with low agreeableness: entitlement and vanity. On the other hand, the leadership facet resembles social dominance, and social dominance tends to increase during this same developmental period (Roberts et al., 2006). Thus, we hypothesized that the entitlement (H2a) and vanity (H2b) facets would decrease, whereas the leadership facet (H2c) would increase from young adulthood to middle age1.

We are only aware of three longitudinal studies that report mean-level change in narcissism or components of narcissism during young or middle adulthood. First, data from 103 individuals who participated in the Block and Block Longitudinal Project (Block & Block, 1980) demonstrated that observer-reported narcissism increased significantly from ages 14 to 18, followed by a small decrease in narcissism from ages 18 to 23 that was not statistically significant (Carlson & Gjerde, 2009). Second, Edelstein, Newton, and Stewart (2012) examined data from 70 women who graduated from Radcliffe College in 1974 and were interviewed when they were 43 and 53 years old. Significant mean change occurred over this 10-year period in all three subscales of narcissism: there were decreases in hypersensitivity (e.g., defensiveness and hostility) and autonomy (e.g., independence and high aspirations), whereas there was an increase in willfulness (e.g., self-indulgence, manipulativeness, and impulsivity; Edelstein et al., 2012). Lastly, Grosz et al. (2017) found that mean levels of self-reported narcissistic admiration (an agentic, assertive component of narcissism) did not change over a 10-year period spanning ages 19 to 29 for two cohorts of German young adults (N1 = 4,962 and N2 = 2,572).

Although these studies provide an important first step toward understanding developmental trends in narcissism, they do not provide a clear picture of how narcissism changes across young adulthood and midlife. In addition to the mixed results, the extant studies suffer from a variety of methodological problems; Carlson and Gjerde (2009) and Edelstein et al. (2012) used small sample sizes, Grosz et al. (2017) only investigated one facet of narcissism, and all studies had limited temporal windows. In contrast, the current study uses a somewhat larger sample size, examines multiple facets of narcissism, covers a longer timeframe over which to observe potential declines in narcissism, and examines change across a developmental period when we would expect the majority of personality change to occur. Thus, we hope the current study will help clarify past inconsistencies, and increase our understanding of how narcissism develops from young adulthood to midlife.

Narcissism and Life Experiences

In addition to examining rank-order consistency and mean-level change, we investigated life events and circumstances that might be associated with narcissism such that (a) having higher narcissism during young adulthood increases the likelihood of the event occurring at a later time (i.e., selection effects) or (b) having an event occur increases the likelihood of observing changes in narcissism (i.e., socialization effects). We examined life events and experiences from three domains: work (e.g., career success and vocational choice), relationships (e.g., relationship status and number of children), and health and well-being (e.g., body mass index and subjective well-being).

Does Narcissism Predict Life Events and Circumstances? - Selection Effects

The type of life events an individual experiences are not completely random, but result in part from individual differences in personality (Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg, 2007). In other words, life experiences are partially attributable to people selecting themselves into experiences that fit their distinct personalities or being selected for these experiences by others (Headey & Wearing, 1989; Magnus, Diener, Fujita, & Pavot, 1993; Roberts, 2006). In particular, research has linked personality traits to a greater probability of experiencing positive and negative life events (Lüdtke, Roberts, Trautwein, & Nagy, 2011; Magnus et al., 1993; Vaidya, Gray, Haig, & Watson, 2002). For example, extraversion is related to the occurrence of positive events, whereas neuroticism predicts experiencing negative life events (e.g., Vaidya et al., 2002). Consistent with past personality research, we investigate whether initial narcissism predicts the occurrence of positive and negative life events.

Despite the growing literature on personality and life events, there is very little research specifically examining narcissism’s relationship with life events. Of the two published studies, Orth and Luciano (2015) found people high on narcissism tended to experience more stressful events over six months, reporting the ‘serious illness of someone close to you’ and having a ‘serious conflict with a family member or friend’. The latter result was attributed to narcissistic individuals’ toxic interpersonal style (Raskin & Terry, 1988) and impulsivity (Vazire & Funder, 2006). Similarly, Grosz et al. (2017) found that young adults higher in narcissistic admiration experienced more negative agentic events (i.e., events that participants evaluated negatively and that experts rated as high in agency, such as those “related to competence, extraversion, uniqueness, separation, and focus on the self,” p. 3). Cross-sectional research indicates that narcissists tend to be high in agency and low in communion—they value power, recognition, and prestige, but do not value close relationships (Campbell & Foster, 2007; Campbell, Rudich, & Sedikides, 2002; Miller, Price, Gentile, Lynam, & Campbell, 2012). Thus, our study investigates whether narcissism predicts life events from two perspectives: (1) participants’ ratings of the positive or negative impact of the life events and (2) expert ratings of the agency and communion of life events. Examples of agentic life events include changing careers, failing an important project, and financial problems, whereas those for communal life events include beginning a serious relationship, getting married, getting divorced, and having children. Based on previous research we predicted that people higher on narcissism would experience more agentic life events (H3) and fewer communal life events (H4) than people lower on narcissism.

Previous research also indicates that narcissism may be related to specific life experiences or outcomes. For instance, Campbell, Hoffman, Campbell, and Marchisio (2011) found that people high on narcissism tend to hold leadership positions more often than people low on narcissism. Wille, De Fruyt, and De Clercq (2013) scored narcissistic tendencies from Big Five data obtained from college alumni prior to entering the job market and found that narcissistic tendencies predicted the managerial level of their current job 15 years later, though narcissistic tendencies did not predict income or number of subordinates. In addition, narcissism appears to be related to economic life goals with more narcissistic individuals aiming at having a high standard of living and wealth and an influential and prestigious occupation (Roberts & Robins, 2000).

In the domain of romantic relationships, narcissism is negatively related to relationship satisfaction and commitment (Lavner, Lamkin, Miller, Campbell, & Karney, 2016; Tracy, Cheng, Robins, Trzesniewski, 2009), and positively related to susceptibility to infidelity (Brewer, Hunt, James, & Abell, 2015). For example, in a longitudinal analysis of married couples, Lavner and colleagues (2016) showed that higher narcissism in wives was related to steeper declines in marital satisfaction and steeper increases in marital problems during the first four years of marriage. Facet-level analyses indicated that these effects were due to the grandiose exhibitionism and entitlement/exploitativeness facets, whereas leadership/authority was not related to marital satisfaction and marital problems. Furthermore, several studies reported that narcissism is negatively related to relationship commitment (Campbell & Foster, 2002; Foster, Shrira, & Campbell, 2006). Lastly, in a study of 107 married couples, Buss and Shackelford (1997) found that narcissism predicted the susceptibility to engage in infidelity in the first year of marriage.

We also examine psychological and physical health. Narcissism’s relationship with psychological health outcomes is somewhat controversial—some research suggests that narcissism is a self-defense mechanism that insulates the narcissist from psychological distress (Sedikides, Rudich, Gregg, Kumashiro, & Rusbult, 2004), whereas other research suggests that narcissism is indicative of unstable, fragile self-esteem (Tracy et al., 2009; Zeigler-Hill, 2006), which particularly in the long-term, may predict greater distress because life outcomes are unlikely to live up to narcissists’ inflated expectations. Furthermore, narcissism has been linked to potentially problematic health behaviors, such as drinking and drug use (Luhtanen & Crocker, 2005; Stenason & Vernon, 2016).

Narcissism thus appears to be prospectively associated with a variety of different life events and experiences. Therefore, we test whether individuals with high versus low levels of narcissism are likely to experience career success, vocational choice, relationship outcomes, subjective well-being, and physical health. Because prior research has only addressed whether narcissism predicts life events in early young adulthood and not into middle age, our analyses are explicitly exploratory.

Which Life Events and Experiences are Associated with Changes in Narcissism? - Socialization Effects

Finally, we examined whether life events and experiences were related to individual differences in change in narcissism over time. Past research has established that significant life events predict personality trait change. For example, positive events are associated with increasing levels of extraversion and negative events with increasing levels of neuroticism (Vaidya et al., 2002), being more invested in work is linked to increasing conscientiousness (Hudson, Roberts, & Lodi-Smith, 2012; Roberts, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2003), a person’s first serious relationship predicts both decreasing neuroticism and increasing conscientiousness (Neyer & Asendorpf, 2001), and being in a healthy relationship predicts declines in negative emotionality (Robins, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2001).

As mentioned above, Orth and Luciano (2015) found that narcissism was linked to experiencing a greater number of stressful events; however, they also reported that changes in narcissism were not related to these stressful events. Conversely, Grosz et al. (2017) found that narcissistic admiration increased over a ten-year period for people who changed their eating/sleeping habits or experienced a romantic break-up when these events were positively evaluated. Narcissistic admiration also increased for people who reported being negatively impacted by a failure on an important exam.

Given the nascent nature of the literature, our analyses of whether positive and negative life events or individual experiences are related to changes in narcissism were exploratory, with one exception: Because prestigious jobs offer more reinforcement to people high on narcissism (attention, admiration, leading others, feeling superior to others), we expected that people in more prestigious jobs would experience a smaller mean-level decrease in narcissism than people in less prestigious jobs (H5). Prior research has shown indirect support for this hypothesis in that jobs with higher prestige were associated with increases in social potency, a facet of social dominance (Roberts et al., 2003). Furthermore, jobs that afforded more material benefits—which also reflected higher occupational attainment—were associated with increases in self and observer reported agentic positive emotionality (Le, Donnellan, & Conger, 2014).

The Present Study

This study is the first long-term longitudinal study addressing rank-order consistency and mean-level changes in narcissism and its facets from young adulthood to middle age. To test our hypotheses, we followed up a sample of Berkeley undergraduates approximately 23 years after they completed a measure of narcissism during their first year in college. This time-lag enabled us to examine whether participants’ narcissism levels predicted later life events and experiences as well as whether life events and experiences in turn predicted mean-level changes in narcissism. Our hypotheses were as follows:

H1: Mean-level narcissism will decrease with age.

H2a: Mean-level entitlement will decrease with age.

H2b: Mean-level vanity will decrease with age.

H2c: Mean-level leadership will increase with age.

H3: People who are more narcissistic will experience fewer communal events2.

H4: People who are more narcissistic will experience more agentic events.

H5: People in more prestigious jobs will experience a smaller mean-level decrease in narcissism.

Method

This study uses data from the Berkeley Longitudinal Study (BLS; Robins & Beer, 2001). The BLS is composed of a cohort of students who entered college at the University of California, Berkeley in 1992 and participated in six assessments that occurred between the first week of college and the end of the fourth year of college. This cohort of students was then subsequently assessed for a seventh time between 2013 and 2016. Notably, narcissism was only assessed twice, during the first week of college and approximately 23 years later. Because the first six data collections have been described in depth elsewhere (e.g., Robins & Beer, 2001; Robins, Fraley, Roberts, & Trzesniewski, 2001), we focus our description on the seventh and most recent data collection. This assessment will be referred to as “age 41” and the first assessment will be referred to as “age 18.” For the age 41 assessment, participants’ updated contact information was obtained through online searches and databases. We then reached out to participants via multiple methods (email, phone, postcards) and asked them to complete our online survey. Participants were compensated with a $25 Amazon gift card that was increased to $50 during the final year of data collection. This study was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (protocol number 13550) and the University of California, Davis (protocol number 529790–1).

The BLS data have been used in numerous previous publications, the vast majority of which did not include narcissism. Four studies analyzed the age 18 narcissism data (Chung, Schriber, & Robins, 2016; Roberts & Robins, 2000; Robins & Beer, 2001; Wetzel et al., 2017), but these studies focused on entirely different research questions than the present study. In addition, none of the previous publications included any analyses of the age 41 data. A data set with the item-level NPI data for age 18 and age 41 and the life event aggregates can be downloaded from https://osf.io/5rd3t/. We cannot make the full data set available because the data would be easily re-identifiable.

Sample

The original sample included 519 participants (56% female), who were on average 18.59 years old (SD = 2.80) at the first assessment. Two hundred forty-eight participants took part in the age 41 assessment (a 48% retention rate relative to the original sample or 59% relative to the number of people for whom contact information could be obtained 23 years later). Of these 248 participants (Mage = 40.94, SD = 1.33), 11 were removed because they did not respond correctly to one or both instructed response items3. Further, 22 participants who did not complete any NPI items at age 18 and did not participate at age 41 were excluded from the analyses. Thus, the final sample size for analyzing change in narcissism was 486 at age 18 and 237 at age 41. In this final sample, 56% were women and 41% were Asian, 35% Caucasian, 13% Latino, 6% African American, 1% Native American, and 4% did not report their ethnicity. At age 41, 1% of the participants reported having completed a high school or two-year community college education, 35% reported having earned a four-year college degree, 33% a Master’s degree, 8% a doctoral degree (PhD), and 23% a medical (MD) or law degree (JD). The majority of the participants were employed (89%) at age 41. In terms of relationship status at age 41, most participants were married (67%) with the remaining participants categorizing themselves as single (17%), in a serious relationship (12%), or divorced (4%).

Attrition analyses with α = 0.01 showed that participants who dropped out did not differ from participants who took part in the age 41 assessment with respect to their average narcissism score (t(428) = 1.63, p = .105, d = 0.14, 95% CI = [−0.03, 0.32]), their socioeconomic status (t(475) = 1.36, p = .176), or their gender (χ2 = 2.92, p = .087). Continuers showed significantly higher high school GPAs (t(498) = 3.16, p = .002, d = 0.28), verbal SAT scores (t(485) = 2.67, p = .008, d = 0.24), and mathematical SAT scores (t(490) = 2.78, p = .006, d = 0.25) than drop-outs, though the effects sizes were all small.

Preregistration of hypotheses

We preregistered our hypotheses on the Open Science Framework prior to analyzing the data (https://osf.io/n9vf8/).

Measures

Descriptive statistics for all measures are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Life Events Indices and Individual Experiences at Age 41

| Measure | Median | M (SD) | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work-related experiences | ||||

| Salary | 97,000 | 122,315 (101,660) | 0 | 690,000 |

| Number of people supervised | 4 | 12 (18.09) | 0 | 101 |

| Power index | 1 | 1.44 (1.22) | 0 | 3 |

| Job prestige | 5 | 5.08 (1.03) | 2 | 7 |

| Job satisfaction | 4 | 3.74 (0.87) | 1 | 5 |

| Realistic | 1.67 | 2.66 (1.57) | 1 | 7 |

| Investigative | 3.67 | 3.97 (1.94) | 1 | 7 |

| Artistic | 2.33 | 2.80 (1.45) | 1 | 7 |

| Social | 3.67 | 4.15 (1.86) | 1 | 7 |

| Enterprising | 5 | 4.88 (2.00) | 1 | 7 |

| Conventional | 3.67 | 4.02 (1.41) | 1 | 7 |

| Relationship-related experiences | ||||

| Relationship satisfaction | 3.8 | 3.7 (0.95) | 1 | 5 |

| Number of children | 2 | 1.99 (0.7) | 1 | 4 |

| Years married | 12 | 11.76 (4.60) | 2 | 21 |

| Health and well-being | ||||

| Self-rated health | 4 | 3.86 | 1 | 5 |

| Hospital frequency | 2 | 2.02 | 1 | 5 |

| Body mass index | 23.65 | 24.86 (5.17) | 17.23 | 46.41 |

| Life satisfaction | 4 | 3.90 (1.08) | 1 | 5 |

| Well-being | 3.65 | 3.51 (0.45) | 1.75 | 4 |

| Life events | ||||

| Index positive life events | 4 | 3.78 (2.18) | 0 | 11 |

| Index negative life events | 2 | 1.97 (1.92) | 0 | 14 |

| Dichotomous variables | % No | % Yes | ||

| Supervise | 40 | 60 | ||

| Hire | 34 | 66 | ||

| Fire | 61 | 39 | ||

| Budget | 54 | 46 | ||

| Intimate relationship | 21 | 79 | ||

| Children | 39 | 61 | ||

Note. Salary and supervise number were analyzed as log-transformed variables. An outlier of 1000 on supervise number was recoded to 101. Sample sizes ranged from 143 (hire) to 237 (majority of the variables).

Narcissism.

A 33-item, forced-choice version of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI; e.g., Robins & Beer, 2001) was used to measure overall narcissism, as well as three narcissism facets: leadership, vanity, and entitlement. For extensive psychometric analyses of this NPI version see Wetzel et al. (2017). The facet structure was obtained in an exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM; Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009) analysis of the age 18 data and is shown in supplemental Table S1. Thirteen items loaded on leadership (e.g., “Being an authority doesn’t mean that much to me” vs. “People always seem to recognize my authority”), nine on vanity (e.g., “I like to look at myself in the mirror” vs. “I am not particularly interested in looking at myself in the mirror”), and seven on entitlement (e.g., “I will never be satisfied until I get all that I deserve” vs. “I take my satisfactions as they come”). Item 22 (“I sometimes depend on people to get things done” vs. “I rarely depend on anyone else to get things done”) was removed because it did not load significantly on overall narcissism or any of the narcissism facets, leaving us with a 32-item measure. Omega total reliabilities were .83 (.86) for overall narcissism scores at age 18 (age 41) and .82 (.82) for leadership, .76 (.80) for vanity, and .61 (.55) for entitlement at age 18 (age 41). Observed correlations between overall narcissism and the facets of narcissism for age 18 and age 41 are depicted in supplemental Table S2.

Life events.

At age 41, participants were asked to indicate whether a list of 17 life events (including got married, started a new job, and experienced a serious personal illness or injury) had occurred during the past 10 years. For events that had occurred, participants also rated the impact of the event on a five-point scale with the labels 1 = extremely negative impact, 3 = neutral, and 5 = extremely positive impact. Participants could also add and rate the impact of up to five other life events. Table S3 in the supplemental material depicts a list of the life events, the percentage of participants who reported that the event had occurred, and average impact ratings. Of the 17 events, seven were agentic, seven were communal, and three were neither agentic nor communal (see Table S3)4. To investigate how life events were related to narcissism and changes in narcissism, we conducted analyses on the individual life events as well as on aggregate measures. For the individual life events, we analyzed whether their occurrence was related to narcissism and changes in narcissism. In addition, we created two types of aggregate measures. The first were aggregate measures of the number of agentic and communal life events a person had experienced. The second were aggregate measures of the number of positive and negative life events using participants’ impact ratings. In particular, events rated as a 4 or 5 were considered positive, whereas events rated as a 1 or 2 were considered negative. Life events rated as neutral (3) were not included in the aggregate measures. Correlations between life event indices and individual life experience variables are shown in supplementary Tables S4 and S5. The life event aggregates were centered prior to analyzing selection and socialization effects to facilitate interpretation.

Work-related experiences.

A number of work-related items were used to assess participants’ career success at age 41. First, participants reported their current annual salary (open-ended). Further, participants reported whether they supervised people directly (yes/no). If they responded with “yes”, they were also asked how many people they supervised directly (open-ended) and whether they could hire employees (yes/no). Participants answered two additional dichotomous (yes/no) questions about their responsibilities: “Can you fire employees?” and “Are you responsible for a budget?” We summed the responses to the three dichotomous supervision-related questions (supervise, fire, budget) to capture an overall assessment of participants’ supervisory responsibilities which we refer to as “power index.” Salary and the number of people supervised were log-transformed prior to analysis.

To provide an additional indicator of career success, we coded the prestige of each participant’s job, using the Occupational Information Network (O*NET; Peterson et al., 2001), a comprehensive database developed by the U.S. Department of Labor. Our first step was to have two researchers independently match each participant’s job with an O*NET code. The coders achieved initial agreement of 68%, which is reasonably high given that there are 974 different job titles to choose from in the O*NET database, and comparable to the level of agreement found at this coding stage by other researchers (see Damian, Spengler, & Roberts, 2017). The majority of the discrepancies were minor, and the coders discussed these discrepancies until consensus was reached. To capture occupational prestige, we examined the O*NET work value labeled recognition, “occupations that satisfy this work value offer advancement, potential for leadership, and are often considered prestigious” (https://www.onetonline.org/link/details/11-1011.00). The O*NET ratings for recognition were provided by trained subject matter experts who were instructed to ask themselves, “To what extent does this occupation satisfy this work value?” using a 1–7 scale with anchors from small to great [see (Rounds, Armstrong, Liao, Lewis, & Rivkin, 2008) for more details]. Jobs high in recognition include surgeons, lawyers, and chief executives, whereas jobs low in recognition include office managers, farm laborers, and product promoters. In the analyses, we used the mean across raters downloaded from https://www.onetcenter.org/dictionary/22.2/text/work_values.html.

Job satisfaction was assessed with a single item, “Overall, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with your current/most recent job?” Participants responded on a five-point scale from completely dissatisfied to completely satisfied. Vocational interest ratings were obtained from O*NET. We used scores on each of Holland’s (1959; 1997) six vocational interest categories (realistic, investigative, artistic, social, enterprising, and conventional; RIASEC). The RIASEC scores were provided by trained experts who determined how characteristic each of Holland’s dimensions was for a particular job—from 1 = not at all characteristic to 7 = extremely characteristic [see (Rounds, Smith, Lawrence, Lewis, & Rivkin, 1999) for more details]. In the analysis, we used the mean across raters (downloaded from https://www.onetcenter.org/dictionary/22.2/excel/interests.html) for each participant’s job. For example, a regional sales manager received a score of 3.67 on realistic, 2 on investigative, 1 on artistic, 3 on social, 6 on enterprising, and 6.33 on conventional.

Relationship-related experiences.

Relationship status at age 41 was assessed with the response categories single/not dating, single/dating, steady boyfriend/girlfriend, living with partner, married, and divorced. Relationship status was recoded into a dichotomous variable with 1 = in an intimate relationship (comprising the categories steady boyfriend/girlfriend, living with partner, and married) and 0 = not in an intimate relationship (comprising the remaining categories). Married participants also provided the date when they were married, which was used to calculate the total number of years a person had been married (until 2017). In addition, participants reported whether they had children (yes/no) and the number of children. Lastly, participants completed the 5-item relationship satisfaction subscale of the Investment Model Scale (Rusbult, Martz, & Agnew, 1998). A sample item is “My relationship is close to ideal.” Mean scores on relationship satisfaction had an omega total reliability of 0.95.

Health and well-being.

Participants rated their physical health on a single-item, five-point scale ranging from poor to excellent. They also reported how often they had gone to the hospital or seen a doctor in the past year on a five-point scale from never to more than once a month. In addition, we asked participants to provide their current height and weight. These variables were used to compute body mass index (BMI): . Life satisfaction was assessed with a single item (“How satisfied or dissatisfied are you with your life as a whole?”) using the response categories very dissatisfied, dissatisfied, neutral, satisfied, and very satisfied. In addition, depression was assessed using the mean of the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Example items include, “I had crying spells.” and “I felt lonely.” Participants rated how often they felt or behaved in ways consistent with each item during the past week on a four-point scale from rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day) to most or all of the time (5–7 days). Depression was recoded in the direction of well-being for analysis. Mean scores on well-being showed an omega total reliability of 0.93.

Pre-analyses on longitudinal measurement invariance

We tested longitudinal measurement invariance in separate models for overall narcissism and the narcissism facets using an iterative procedure starting with a fully constrained model (see Wetzel et al., 2017). Importantly, this procedure relied on significance testing for non-invariance as well as an effect size criterion to ensure that only at least small to moderate non-invariance was taken into account. The underlying measurement model was the Thurstonian item response model (Brown & Maydeu-Olivares, 2011), which takes the dependencies between items presented in a pair into account. Parameters (loadings, intercepts) that were noninvariant were consecutively freed until the final partial measurement invariance model was obtained. In total, two loadings and seven intercepts were freed for overall narcissism and four loadings and seven intercepts were freed for the narcissism facets. The subsequent analyses on mean-level changes and relations to life events and individual outcomes were all based on the final partial invariance models (i.e., non-invariance was controlled for in the analyses of change). Supplemental Tables S6 and S7 contain a list of the freed parameters for overall narcissism and the facets of narcissism, respectively.

Analyses

Rank-order consistency.

Latent correlations between age 18 and age 41 from the final partial invariance models were used to investigate the rank-order consistency of overall narcissism and the narcissism facets. We first modeled the facets individually in three separate models and then simultaneously in one model. In the latter model, the facets were allowed to correlate within as well as across waves. This analysis indicates whether individuals who were relatively high (or low) on narcissism as young adults tended to remain relatively high (or low) on narcissism when they were middle aged.

Mean-level changes.

To test whether mean levels in narcissism and the narcissism facets changed from age 18 to age 41, we fit latent change models (Steyer, Eid, & Schwenkmezger, 1997) to the data. Figure 1 shows the structure of the model for overall narcissism. The latent change model consists of measurement models for age 18 and age 41 as well as a latent intercept variable representing the mean level at age 18 and a latent change variable representing the change from age 18 to age 41. We modeled overall narcissism and each of the facets separately. As an additional test of H2c, which proposed an increase in the leadership facet, we ran a model that controlled for the overlap between leadership and the other two facets, vanity and entitlement. In this model, we regressed leadership at age 18 on vanity and entitlement at age 18 and regressed leadership at age 41 on vanity and entitlement at age 41. The latent variables for level and change in leadership were extracted from the residualized age 18 and age 41 leadership variables in the same model. This model did not contain level and change variables for vanity and entitlement. In addition, the correlations between the level and change variables for leadership and the latent variables for vanity and entitlement at age 18 and age 41 were fixed to 0. Sample size in this study was mainly determined by the number of people we could track down for the age 41 assessment and who were willing to participate. Nevertheless, we also conducted Monte Carlo simulations (Muthén & Muthén, 2002) to estimate our power for detecting small (0.20), moderate (0.50), and large (0.80) effects for the mean-level changes in the latent change models. For small effects, our power was inadequate and ranged from 0.48 (entitlement) to 0.69 (leadership). For moderate and large effects, however, our power was excellent for overall narcissism and all facets (1.00 in all cases).

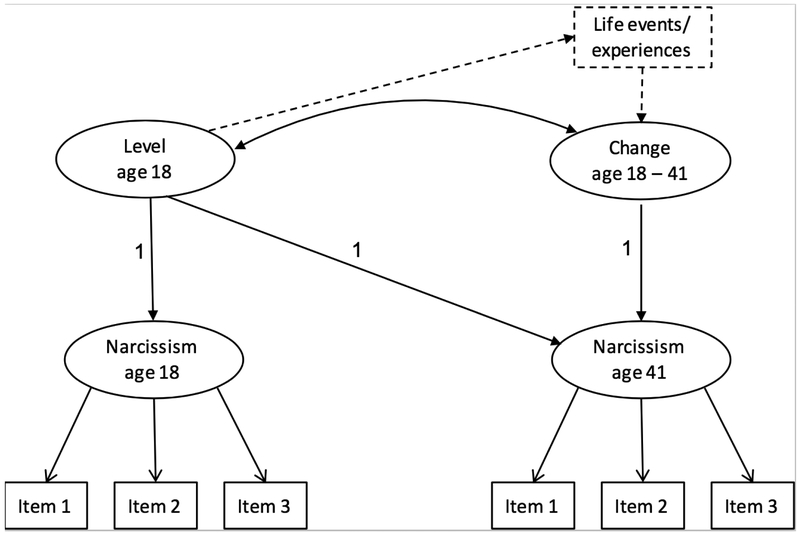

Figure 1.

Structure of the latent change models testing mean−level changes in narcissism. For testing selection and socialization effects, regressions with life events or an individual experience variable were added (see dashed lines). For clarity of presentation only three items are shown. “1” indicates paths that were fixed to 1.

In addition, to quantify the number of people whose narcissism levels increased, decreased, or stayed the same from age 18 to 41, we used a modified version of the Reliable Change Index (RCI; Jacobson & Truax) based on latent trait estimates (maximum a posteriori estimates; MAP) and individual standard errors for these latent trait estimates. Thus, with . The latent trait estimate RCI is more accurate than a conventional RCI because it takes into account longitudinal measurement invariance. An RCI > 1.96 indicates a reliable increase; an RCI < −1.96 indicates a reliable decrease; and values in between indicate no reliable change.

Selection and socialization effects.

To test for selection and socialization effects, either the life event aggregates or an individual experience variable were added to the latent change model (see dashed lines in Figure 1). To test for selection effects, we investigated the degree to which narcissism at age 18 predicted work, relationship, and health-related experiences at age 41, including the number of positive and negative life events. We analyzed selection and socialization effects in separate models for overall narcissism and each of the facets as well as in a model with all facets entered simultaneously. The latter model controls for the overlap between the facets by using them as simultaneous predictors of life events and life experiences. In this model, the intercept variables of the three facets were allowed to correlate and the change variables were allowed to correlate. In addition, we examined whether the work, relationship, and health-related experiences and life event measures predicted change in narcissism from age 18 to 41. In the models of aggregated positive and negative life events, the correlation between positive and negative life events was also included. Because these analyses were exploratory with the exception of the relation between overall narcissism and agentic and communal life events, we refrained from significance testing and report only point estimates with their 95% confidence intervals. Because the study was exploratory and not optimally powered to detect small effects, we have chosen to note and interpret prospective relations that were functionally equivalent to a .25 d-score.

Results

Rank-order consistency

Overall narcissism and all of the facets showed high rank-order consistency across the 23-year period from young adulthood to middle age. The latent correlation between age 18 and age 41 was 0.69 for overall narcissism. When the facets were modeled separately, the latent correlation between age 18 and age 41 was 0.67 for leadership, 0.61 for vanity, and 0.85 for entitlement. In a model with all facets, the estimates were very similar with latent correlations of .70 for leadership, .60 for vanity, and .77 for entitlement.

Mean-level changes

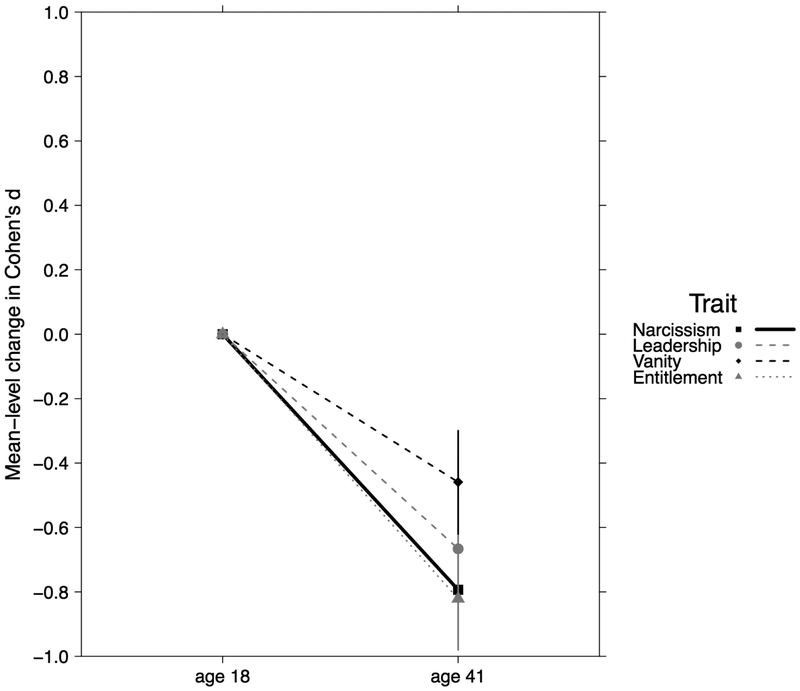

Overall narcissism and all three narcissism facets decreased from age 18 to age 41. Mean estimates and Cohen’s d values are depicted in Table 2 and Figure 2. On average, overall narcissism decreased by d = −0.79 (95% CI = [−0.95, −0.63]) over the 23-year period from the first year of college to middle age. At the level of the individual facets, the smallest decrease occurred for vanity (d = −0.46, 95% CI = [−0.62, −0.30]) and the largest decrease occurred for entitlement (d = −0.82, 95% CI = [−0.98, −0.66]). We also observed a decrease in the leadership facet (d = −0.67, 95% CI = [−0.83, −0.51]). When we regressed leadership at age 18 and age 41 on vanity and entitlement at age 18 and age 41, the decrease in leadership was reduced to d = −0.22 (95% CI = [−0.38, −0.06])5. Thus, our hypotheses on mean-level changes were supported for overall narcissism, vanity, and entitlement. However, the decrease we found in leadership was contrary to our hypothesis that this facet would increase6.

Table 2.

Mean-level Changes in Narcissism and the Facets of Narcissism

| Trait | M Δ age 18 – age 41 | SD Δ age 18 – age 41 | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall narcissism | −0.71 [−0.89, −0.52] | 0.89 | –0.79 [–0.95, −0.63] |

| Facets modeled separately Leadership | −0.53 [−0.69, −0.37] | 0.79 | −0.67 [−0.83, −0.51] |

| Vanity | −0.45 [−0.64, −0.25] | 0.97 | −0.46 [−0.62, −0.30] |

| Entitlement | −0.43 [−0.70, −0.16] | 0.52 | −0.82 [−0.98, −0.66] |

| Leadership controlled for vanity and entitlement Leadership | −0.16 [−0.40, 0.07] | 0.75 | −0.22 [−0.38, −0.06] |

Note. Values in brackets are 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2.

Mean-level decreases (d) in overall narcissism and its facets (modeled individually) from age 18 to age 41. The mean was fixed to 0 at age 18 for identification. Bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

For overall narcissism and the separately modeled leadership and vanity facets, the latent change variable showed significant variance ranging from 0.63 (p < .001) for leadership to 0.95 for vanity (p <.001), indicating that participants differed in the degree and potentially also the direction of their change. Entitlement did not show significant variance in the latent change variable when the facet were modeled separately (0.27, p = .099). To quantify the number of people that had changed reliably, we additionally computed latent trait estimate RCIs. Supplemental Table S8 shows the distribution of the latent trait estimate RCIs for overall narcissism and the three facets. The majority of participants (72% for overall narcissism to 95% for entitlement) did not show reliable increases or decreases from age 18 to 41; between 5% (entitlement) and 25% (overall narcissism) showed a reliable decrease; and, no participants (entitlement) or extremely few participants (3% for overall narcissism and vanity) showed a reliable increase. As plots of the individual RCIs for overall narcissism and each of the facets show (see supplemental Figure S1), the majority of participants appeared to decrease, though many did not exceed the threshold for reliable change.

Selection and socialization effects

Does Narcissism Predict Life Events and Circumstances? - Selection Effects

First, we tested the relation between the initial level of narcissism and each of its facets and the various life outcomes measured at age 41 to see whether narcissism was related to the occurrence of any particular types of life events and experiences. Students who scored higher on the entitlement facet at age 18 reported more negative life events at age 41 (β = 0.19, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.35], see Table 3). Overall narcissism was not related to the number of agentic or communal life events a person had experienced between age 31 and age 41.

Table 3.

Standardized Regression Coefficients from Analysis of Age 18 Narcissism Predicting Life Experiences (Selection Effects) and Life Experiences Predicting Change in Narcissism from Age 18 to 41 (Socialization Effects)

| Selection effect (narcissism age 18 → life events) | Socialization effect (life events → Δ age 18 – age 41) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | Index | β | β |

| Overall narcissism | Positive life events | 0.12 [−0.05, 0.28] | 0.07 [−0.09, 0.24] |

| Negative life events | 0.07 [−0.08, 0.22] | 0.01 [−0.14, 0.16] | |

| Agentic life events | 0.08 [−0.07, 0.24] | 0.12 [−0.04, 0.27] | |

| Communal life events | 0.13 [−0.02, 0.28] | 0.12 [−0.03, 0.26] | |

| Facets modeled separately | |||

| Leadership | Positive life events | 0.12 [−0.04, 0.27] | 0.09 [−0.06, 0.23] |

| Negative life events | 0.09 [−0.07, 0.24] | −0.09 [−0.23, 0.06] | |

| Agentic life events | 0.10 [−0.06, 0.25] | 0.07 [−0.08, 0.22] | |

| Communal life events | 0.09 [−0.06, 0.23] | 0.06 [−0.07, 0.19] | |

| Vanity | Positive life events | 0.16 [0.01, 0.32] | 0.06 [−0.11, 0.23] |

| Negative life events | −0.03 [−0.18, 0.12] | 0.21 [0.06, 0.36] | |

| Agentic life events | 0.03 [−0.12, 0.18] | 0.21 [0.05, 0.37] | |

| Communal life events | 0.19 [0.04, 0.33] | 0.19 [0.02, 0.35] | |

| Entitlement | Positive life events | −0.11 [−0.28, 0.06] | −0.10 [−0.39, 0.18] |

| Negative life events | 0.19 [0.02, 0.35] | −0.07 [−0.38, 0.23] | |

| Agentic life events | 0.11 [−0.05, 0.28] | −0.12 [−0.45, 0.21] | |

| Communal life events | 0.01 [−0.16, 0.18] | −0.02 [−0.3, 0.27] | |

| Facets modeled simultaneously | |||

| Leadership | Positive life events | 0.14 [−0.04, 0.31] | 0.06 [−0.10, 0.23] |

| Negative life events | 0.07 [−0.11, 0.25] | −0.11 [−0.27, 0.04] | |

| Agentic life events | 0.10 [−0.08, 0.28] | 0.03 [−0.14, 0.2] | |

| Communal life events | 0.05 [−0.12, 0.22] | −0.03 [−0.18, 0.13] | |

| Vanity | Positive life events | 0.15 [−0.01, 0.32] | 0.06 [−0.11, 0.23] |

| Negative life events | −0.11 [−0.27, 0.06] | 0.19 [0.03, 0.35] | |

| Agentic life events | −0.03 [−0.2, 0.13] | 0.21 [0.05, 0.36] | |

| Communal life events | 0.17 [0, 0.34] | 0.20 [0.04, 0.35] | |

| Entitlement | Positive life events | −0.22 [−0.39, −0.04] | −0.10 [−0.4, 0.2] |

| Negative life events | 0.20 [0.01, 0.38] | −0.15 [−0.47, 0.18] | |

| Agentic life events | 0.07 [−0.12, 0.26] | −0.09 [−0.39, 0.2] | |

| Communal life events | −0.03 [−0.23, 0.17] | −0.06 [−0.36, 0.24] | |

Note. Values in brackets are 95% confidence intervals.

In terms of work experiences, individuals who were higher on narcissism in college tended to be in jobs at age 41 that afforded them more control over others. In particular, overall narcissism was associated with supervising more people (β = 0.15, 95% CI = [−0.03, 0.33]), and having the ability to hire people (β = 0.26, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.49]). The leadership facet was associated with supervising more people (β = 0.20, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.38]) and having the power to hire people (β = 0.30, 95% CI = [0.08, 0.52]) as well. Narcissism and the facets of leadership and entitlement were also predictive of having failed at an important project (e.g., (β = 0.35, 95% CI = [0.07, 0.62] for entitlement). Narcissism and its facets were unrelated to salary, job prestige, job satisfaction, financial problems, changing careers or employers, and the types of vocations occupied at age 41 (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Standardized Regression Coefficients from Analysis of Age 18 Narcissism and each of the Individual Facets Predicting Life Experiences (Selection Effects) and Life Experiences Predicting Change in Narcissism from Age 18 to 41 (Socialization Effects)

| Overall narcissism | Leadership | Vanity | Entitlement | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β selection | β socialization | β selection | β socialization | β selection | β socialization | β selection | β socialization | |

| Work related experiences | ||||||||

| Salary | 0.11 [−0.05, 0.27] | 0.05 [−0.11, 0.20] | 0.10 [−0.05, 0.25] | 0.08 [−0.06, 0.22] | 0.01 [−0.15, 0.17] | −0.02 [−0.16, 0.11] | 0.16 [−0.02, 0.33] | −0.02 [−0.34, 0.29] |

| Supervise | 0.16 [−0.03, 0.34] | 0.25 [0.05, 0.46] | 0.13 [−0.05, 0.32] | 0.38 [0.20, 0.55] | 0.06 [−0.14, 0.26] | 0.03 [−0.20, 0.25] | 0.14 [−0.09, 0.37] | −0.26 [−0.68, 0.16] |

| Number of people supervised | 0.15 [−0.03, 0.33] | −0.08 [−0.29, 0.13] | 0.20 [0.02, 0.38] | −0.05 [−0.23, 0.12] | −0.02 [−0.21, 0.17] | −0.04 [−0.27, 0.18] | 0.13 [−0.09, 0.36] | −0.08 [−0.50, 0.34] |

| Hire | 0.26 [0.03, 0.49] | 0.11 [−0.16, 0.37] | 0.30 [0.08, 0.52] | 0.2 [−0.04, 0.43] | 0.04 [−0.23, 0.31] | 0 [−0.27, 0.27] | 0.23 [−0.06, 0.52] | −0.09 [−0.69, 0.52] |

| Fire | 0.17 [−0.02, 0.35] | 0.32 [0.13, 0.51] | 0.15 [−0.03, 0.33] | 0.43 [0.26, 0.60] | 0.06 [−0.14, 0.25] | 0.04 [−0.16, 0.25] | 0.11 [−0.12, 0.34] | 0.03 [−0.36, 0.43] |

| Budget | 0.14 [−0.05, 0.32] | 0.25 [0.05, 0.44] | 0.17 [−0.01, 0.35] | 0.33 [0.16, 0.51] | −0.02 [−0.22, 0.18] | 0.10 [−0.11, 0.32] | 0.15 [−0.08, 0.37] | −0.22 [−0.66, 0.22] |

| Power index | 0.14 [−0.01, 0.29] | 0.27 [0.11, 0.43] | 0.14 [−0.01, 0.28] | 0.36 [0.22, 0.51] | 0.03 [−0.13, 0.18] | 0.06 [−0.11, 0.23] | 0.12 [−0.07, 0.30] | −0.12 [−0.44, 0.20] |

| Prestige | −0.01 [−0.17, 0.15] | −0.02 [−0.21, 0.17] | −0.01 [−0.17, 0.16] | 0.02 [−0.16, 0.19] | −0.09 [−0.26, 0.07] | −0.01 [−0.20, 0.18] | 0.10 [−0.10, 0.30] | −0.18 [−0.56, 0.20] |

| Job satisfaction | 0.01 [−0.11, 0.14] | 0.04 [−0.12, 0.20] | 0.01 [−0.13, 0.14] | 0.07 [−0.08, 0.22] | 0.04 [−0.10, 0.18] | 0.04 [−0.14, 0.22] | −0.08 [−0.24, 0.08] | −0.37 [−0.63, −0.11] |

| Realistic | 0.08 [−0.08, 0.23] | −0.22 [−0.39, −0.05] | 0.02 [−0.14, 0.18] | −0.16 [−0.31, −0.01] | 0.17 [0.01, 0.33] | −0.15 [−0.33, 0.03] | −0.03 [−0.23, 0.17] | −0.13 [−0.47, 0.22] |

| Investigative | −0.03 [−0.20, 0.13] | −0.17 [−0.35, 0] | −0.03 [−0.19, 0.14] | −0.20 [−0.35, −0.04] | −0.05 [−0.22, 0.12] | −0.11 [−0.29, 0.07] | 0.11 [−0.07, 0.30] | 0.07 [−0.24, 0.38] |

| Artistic | −0.03 [−0.19, 0.14] | 0.05 [−0.11, 0.22] | 0.01 [−0.15, 0.17] | 0.04 [−0.11, 0.20] | −0.07 [−0.24, 0.10] | 0.03 [−0.14, 0.19] | 0.02 [−0.19, 0.22] | −0.03 [−0.34, 0.27] |

| Social | −0.01 [−0.17, 0.15] | −0.05 [−0.22, 0.12] | 0.01 [−0.15, 0.16] | −0.02 [−0.17, 0.14] | 0.02 [−0.16, 0.19] | −0.07 [−0.24, 0.10] | −0.01 [−0.21, 0.19] | −0.07 [−0.38, 0.23] |

| Enterprising | 0.07 [−0.10, 0.23] | 0.17 [0, 0.34] | 0.09 [−0.07, 0.24] | 0.19 [0.04, 0.35] | −0.05 [−0.22, 0.12] | 0.09 [−0.08, 0.26] | 0.04 [−0.14, 0.23] | −0.12 [−0.45, 0.21] |

| Conventional | −0.06 [−0.23, 0.1] | 0.12 [−0.06, 0.31] | −0.05 [−0.21, 0.11] | 0.11 [−0.05, 0.27] | −0.03 [−0.21, 0.15] | 0.07 [−0.13, 0.27] | −0.19 [−0.38, 0.01] | 0.01 [−0.3, 0.31] |

| Relationship–related experiences | ||||||||

| Relationship status | 0.05 [−0.16, 0.26] | −0.14 [−0.37, 0.10] | −0.01 [−0.22, 0.21] | 0.01 [−0.21, 0.23] | 0.09 [−0.11, 0.29] | −0.25 [−0.49, −0.01] | −0.02 [−0.26, 0.22] | 0.09 [−0.3, 0.49] |

| Relationship satisfaction | 0.10 [−0.05, 0.24] | 0.05 [−0.14, 0.24] | 0.12 [−0.02, 0.27] | 0.09 [−0.08, 0.25] | −0.01 [−0.16, 0.14] | 0.08 [−0.11, 0.26] | −0.09 [−0.27, 0.09] | −0.2 [−0.51, 0.11] |

| Children | −0.01 [−0.2, 0.18] | −0.01 [−0.21, 0.20] | −0.04 [−0.23, 0.15] | 0.09 [−0.10, 0.28] | 0.12 [−0.08, 0.32] | −0.15 [−0.37, 0.08] | −0.15 [−0.38, 0.07] | 0.19 [−0.17, 0.56] |

| Number of children | −0.17 [−0.36, 0.02] | 0.12 [−0.11, 0.36] | −0.05 [−0.24, 0.14] | 0.07 [−0.11, 0.25] | −0.21 [−0.41, −0.02] | 0.08 [−0.15, 0.32] | −0.23 [−0.53, 0.06] | 0.22 [−0.32, 0.76] |

| Years married | −0.08 [−0.26, 0.11] | 0.06 [−0.14, 0.26] | 0.03 [−0.16, 0.21] | 0.08 [−0.11, 0.27] | −0.23 [−0.42, −0.03] | 0.06 [−0.16, 0.27] | −0.01 [−0.25, 0.24] | 0.19 [−0.15, 0.53] |

| Health and well-being | ||||||||

| Self-rated health | 0.10 [−0.04, 0.24] | 0.07 [−0.10, 0.23] | 0.06 [−0.08, 0.20] | 0.03 [−0.12, 0.18] | 0.22 [0.07, 0.37] | 0.13 [−0.06, 0.32] | −0.13 [−0.3, 0.04] | −0.02 [−0.3, 0.25] |

| Hospital frequency | −0.08 [−0.23, 0.07] | 0.10 [−0.05, 0.24] | −0.04 [−0.18, 0.09] | 0.02 [−0.12, 0.16] | −0.08 [−0.23, 0.07] | 0.10 [−0.07, 0.27] | −0.05 [−0.23, 0.13] | 0.14 [−0.17, 0.45] |

| Body mass index | 0.03 [−0.12, 0.18] | 0.11 [−0.04, 0.26] | 0.04 [−0.11, 0.18] | 0.15 [0.01, 0.29] | −0.07 [−0.21, 0.08] | −0.09 [−0.27, 0.09] | 0.19 [0.01, 0.38] | −0.05 [−0.30, 0.19] |

| Life satisfaction | 0.03 [−0.11, 0.18] | 0.14 [−0.02, 0.31] | 0.06 [−0.08, 0.20] | 0.14 [−0.01, 0.29] | 0.06 [−0.10, 0.21] | 0.14 [−0.03, 0.30] | −0.18 [−0.35, −0.02] | −0.26 [−0.5, −0.03] |

| Well-being | 0.07 [−0.09, 0.22] | 0 [−0.17, 0.18] | 0.07 [−0.08, 0.22] | 0.03 [−0.12, 0.18] | 0.16 [0.02, 0.3] | 0.02 [−0.17, 0.20] | −0.32 [−0.48, −0.17] | −0.31 [−0.57, −0.04] |

| Life events | ||||||||

| Arrested for a crime | 0.18 [−0.16, 0.53] | 0.11 [−0.2, 0.42] | 0.29 [−0.07, 0.65] | 0 [−0.38, 0.38] | 0.04 [−0.35, 0.42] | 0.22 [−0.11, 0.55] | 0.04 [−0.36, 0.43] | 0.22 [−0.26, 0.70] |

| Beginning a serious relationship | 0.14 [−0.05, 0.32] | 0.05 [−0.16, 0.26] | 0.06 [−0.13, 0.24] | 0.03 [−0.17, 0.22] | 0.23 [0.04, 0.42] | 0.13 [−0.09, 0.35] | 0.06 [−0.17, 0.28] | −0.21 [−0.59, 0.17] |

| Breaking up with romantic partner | 0.12 [−0.07, 0.31] | 0.12 [−0.08, 0.33] | 0.08 [−0.11, 0.26] | −0.01 [−0.20, 0.19] | 0.19 [−0.01, 0.38] | 0.28 [0.08, 0.49] | −0.04 [−0.27, 0.19] | −0.02 [−0.39, 0.36] |

| Change careers | −0.06 [−0.26, 0.15] | 0.07 [−0.15, 0.29] | 0 [−0.20, 0.20] | 0.02 [−0.18, 0.22] | −0.08 [−0.29, 0.13] | 0.15 [−0.09, 0.40] | 0 [−0.26, 0.25] | −0.09 [−0.51, 0.33] |

| Change in closeness with parents and/or other family members | 0.08 [−0.12, 0.27] | 0.18 [−0.02, 0.39] | 0.05 [−0.15, 0.24] | 0.16 [−0.03, 0.36] | 0.11 [−0.09, 0.30] | 0.25 [0.04, 0.46] | 0.03 [−0.20, 0.26] | −0.14 [−0.57, 0.28] |

| Change of residence | −0.05 [−0.24, 0.15] | 0.06 [−0.15, 0.28] | 0.02 [−0.18, 0.22] | −0.09 [−0.30, 0.12] | −0.03 [−0.23, 0.17] | 0.22 [0, 0.44] | −0.12 [−0.36, 0.11] | 0.19 [−0.23, 0.61] |

| Change place of employment | 0.02 [−0.18, 0.21] | 0.12 [−0.09, 0.34] | 0.01 [−0.19, 0.20] | 0.14 [−0.06, 0.33] | 0 [−0.19, 0.20] | 0.11 [−0.10, 0.33] | 0.15 [−0.09, 0.38] | −0.15 [−0.59, 0.29] |

| Death or serious illness/injury of a close family member or friend | −0.07 [−0.26, 0.12] | 0.17 [−0.04, 0.37] | 0.07 [−0.12, 0.25] | 0.07 [−0.13, 0.26] | −0.25 [−0.45, −0.05] | 0.25 [0.02, 0.47] | −0.10 [−0.33, 0.13] | −0.01 [−0.40, 0.37] |

| Failing an important project | 0.30 [0, 0.60] | 0.11 [−0.11, 0.34] | 0.28 [0.01, 0.55] | 0.16 [−0.05, 0.38] | 0.23 [−0.06, 0.52] | 0.14 [−0.12, 0.40] | 0.35 [0.07, 0.62] | −0.39 [−1.10, 0.31] |

| Financial problems | 0.14 [−0.08, 0.35] | 0.25 [0.04, 0.46] | 0.12 [−0.10, 0.33] | 0.16 [−0.04, 0.37] | 0.11 [−0.10, 0.31] | 0.33 [0.11, 0.55] | 0.18 [−0.07, 0.43] | −0.20 [−0.63, 0.24] |

| Fired from a job or serious | 0.15 [−0.06, 0.37] | −0.07 [−0.32, 0.19] | 0.16 [−0.06, 0.37] | −0.09 [−0.32, 0.15] | 0.08 [−0.15, 0.31] | 0.07 [−0.17, 0.31] | 0.14 [−0.12, 0.4] | 0.06 [−0.41, 0.53] |

| Got divorced | 0.31 [0.07, 0.55] | −0.10 [−0.43, 0.22] | 0.28 [0.05, 0.52] | −0.12 [−0.39, 0.14] | 0.28 [0.07, 0.49] | 0.08 [−0.23, 0.40] | 0.14 [−0.14, 0.43] | −0.49 [−1.07, 0.08] |

| Got married | 0.10 [−0.09, 0.29] | 0.01 [−0.20, 0.22] | 0.01 [−0.17, 0.19] | 0.03 [−0.16, 0.22] | 0.22 [0.02, 0.42] | −0.08 [−0.31, 0.16] | 0.10 [−0.13, 0.32] | 0.28 [−0.09, 0.65] |

| Had children | −0.01 [−0.20, 0.18] | −0.05 [−0.25, 0.16] | −0.05 [−0.23, 0.14] | 0.01 [−0.18, 0.21] | 0.11 [−0.08, 0.31] | −0.13 [−0.35, 0.08] | −0.08 [−0.31, 0.14] | 0.25 [−0.12, 0.63] |

| Serious personal illness or injury | −0.01 [−0.21, 0.18] | 0.12 [−0.10, 0.33] | 0.03 [−0.17, 0.23] | −0.03 [−0.24, 0.18] | −0.05 [−0.24, 0.15] | 0.24 [0.02, 0.47] | −0.11 [−0.37, 0.14] | −0.04 [−0.45, 0.37] |

| Started a new job | 0.05 [−0.16, 0.25] | −0.03 [−0.24, 0.19] | 0.06 [−0.14, 0.27] | −0.01 [−0.21, 0.19] | 0 [−0.21, 0.21] | 0.07 [−0.15, 0.28] | −0.01 [−0.26, 0.24] | 0.06 [−0.35, 0.47] |

| Victim of a crime | 0.13 [−0.16, 0.42] | −0.13 [−0.37, 0.11] | 0.18 [−0.08, 0.45] | −0.08 [−0.32, 0.15] | 0.02 [−0.26, 0.30] | −0.02 [−0.27, 0.23] | 0.21 [−0.07, 0.48] | −0.88 [−1.6, −0.16] |

Note. Values in brackets are 95% confidence intervals. Selection effect: Narcissism or one of the facets at age 18 predicted the individual life experience or event. Socialization effect: The individual life experience or event predicted change in narcissism or one of the facets from age 18 and age 41.

In terms of family structure and relationships, individuals scoring high on the vanity facet tended to have fewer children (β = −0.21, 95% CI = [−0.41, −0.02]), to register fewer years of marriage (β = −0.23, 95% CI = [−0.42, −0.03]), to get divorced (β = 0.28, 95% CI = [0.07, 0.49]), to get married (β = 0.22, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.42]), and to begin relationships more often (β = 0.23, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.42]). It should be noted that overall narcissism (β = 0.31, 95% CI = [0.07, 0.55]) and the leadership facet (β = 0.28, 95% CI = [0.05, 0.52]) were also associated with experiencing divorce.

In terms of health and well-being, vanity was positively associated with better self-rated health in middle age (β = 0.22, 95% CI = [0.07, 0.37]) and to being less likely to have a close friend or family member suffer a serious disease or death (β = −0.25, 95% CI = [−0.45, −0.05]). In contrast, the entitlement facet was negatively predictive of life satisfaction (β = −0.18, 95% CI = [−0.35, −0.02]) and well-being (β = −0.32, 95% CI = [−0.48, −0.17]), while being positively predictive of BMI (β = 0.19, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.38]).

When the facets were modeled simultaneously, all of the effects from when the facets were modeled separately were also present (except one), and several new effects emerged (see Table 5). Entitlement at age 18 predicted fewer positive life events at age 41 (β = −0.22, 95% CI = [−0.39, −0.04]), in addition to predicting more negative life events. In the relationship domain, leadership at age 18 additionally predicted relationship satisfaction at age 41 (β = 0.24, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.43]; see Table 5).

Table 5.

Standardized Regression Coefficients from Analysis of Age 18 Narcissism Facets Predicting Life Experiences (Selection Effects) and Life Experiences Predicting Change in Narcissism Facets from Age 18 to 41 (Socialization Effects) with all Facets Modeled Simultaneously

| Leadership | Vanity | Entitlement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β selection | β socialization | β selection | β socialization | β selection | β socialization | |

| Work related experiences | ||||||

| Salary | 0.11 [−0.08, 0.30] | 0.06 [−0.11, 0.23] | −0.17 [−0.36, 0.03] | 0.05 [−0.14, 0.24] | 0.21 [−0.03, 0.44] | −0.19 [−0.55, 0.18] |

| Supervise | 0.19 [−0.05, 0.44] | 0.35 [0.15, 0.56] | −0.17 [−0.42, 0.08] | 0.11 [−0.12, 0.34] | 0.08 [−0.22, 0.39] | −0.26 [−0.65, 0.14] |

| Number of people supervised | 0.25 [0.01, 0.48] | −0.05 [−0.25, 0.16] | −0.17 [−0.39, 0.04] | −0.03 [−0.27, 0.21] | 0.07 [−0.19, 0.34] | −0.23 [−0.62, 0.15] |

| Hire | 0.39 [0.1, 0.68] | 0.18 [−0.06, 0.42] | −0.25 [−0.55, 0.05] | 0.08 [−0.21, 0.38] | 0.09 [−0.23, 0.41] | −0.18 [−0.66, 0.3] |

| Fire | 0.23 [−0.01, 0.46] | 0.44 [0.24, 0.64] | −0.19 [−0.43, 0.06] | 0.13 [−0.1, 0.37] | 0.04 [−0.25, 0.34] | −0.05 [−0.47, 0.37] |

| Budget | 0.28 [0.04, 0.51] | 0.35 [0.14, 0.55] | −0.27 [−0.51, −0.02] | 0.16 [−0.1, 0.41] | 0.06 [−0.22, 0.34] | −0.2 [−0.6, 0.21] |

| Power index | 0.2 [0.01, 0.39] | 0.36 [0.19, 0.53] | −0.16 [−0.36, 0.04] | 0.1 [−0.09, 0.29] | 0.05 [−0.19, 0.29] | −0.14 [−0.46, 0.18] |

| Prestige | 0 [−0.2, 0.2] | 0.06 [−0.14, 0.25] | −0.15 [−0.34, 0.05] | −0.01 [−0.18, 0.16] | 0.11 [−0.13, 0.35] | −0.07 [−0.39, 0.25] |

| Job satisfaction | 0.07 [−0.13, 0.28] | −0.03 [−0.24, 0.18] | 0.03 [−0.16, 0.22] | 0.03 [−0.16, 0.23] | −0.08 [−0.28, 0.13] | −0.45 [−0.74, −0.16] |

| Realistic | −0.08 [−0.26, 0.11] | −0.24 [−0.42, −0.07] | 0.24 [0.02, 0.45] | −0.15 [−0.33, 0.02] | −0.02 [−0.25, 0.22] | −0.17 [−0.51, 0.17] |

| Investigative | −0.08 [−0.26, 0.1] | −0.19 [−0.37, −0.02] | −0.05 [−0.24, 0.14] | −0.13 [−0.3, 0.05] | 0.18 [−0.04, 0.4] | 0.02 [−0.28, 0.32] |

| Artistic | 0.05 [−0.14, 0.24] | 0.07 [−0.1, 0.23] | −0.11 [−0.31, 0.09] | 0.03 [−0.12, 0.19] | 0.02 [−0.2, 0.24] | −0.07 [−0.35, 0.21] |

| Social | 0.02 [−0.17, 0.21] | −0.01 [−0.18, 0.16] | 0.01 [−0.17, 0.2] | −0.05 [−0.21, 0.12] | −0.05 [−0.27, 0.17] | 0.04 [−0.24, 0.33] |

| Enterprising | 0.14 [−0.06, 0.33] | 0.2 [0.03, 0.37] | −0.13 [−0.32, 0.07] | 0.08 [−0.09, 0.24] | 0.01 [−0.2, 0.22] | −0.12 [−0.44, 0.2] |

| Conventional | 0.02 [−0.17, 0.22] | 0.15 [−0.02, 0.33] | 0.01 [−0.21, 0.22] | 0.07 [−0.11, 0.24] | −0.22 [−0.45, 0.02] | 0.05 [−0.24, 0.34] |

| Relationship–related experiences | ||||||

| Relationship status | −0.09 [−0.35, 0.17] | −0.01 [−0.26, 0.23] | 0.16 [−0.09, 0.42] | −0.26 [−0.5, −0.02] | −0.03 [−0.31, 0.24] | 0.07 [−0.33, 0.46] |

| Relationship satisfaction | 0.24 [0.04, 0.43] | 0.09 [−0.11, 0.29] | −0.13 [−0.32, 0.07] | 0.09 [−0.14, 0.32] | −0.09 [−0.32, 0.14] | −0.26 [−0.64, 0.11] |

| Children | −0.08 [−0.32, 0.16] | 0.07 [−0.15, 0.29] | 0.22 [−0.02, 0.45] | −0.17 [−0.41, 0.07] | −0.2 [−0.45, 0.04] | 0.14 [−0.24, 0.53] |

| Number of children | 0.01 [−0.3, 0.31] | 0.35 [0.03, 0.67] | −0.28 [−0.59, 0.04] | −0.03 [−0.41, 0.35] | −0.13 [−0.48, 0.22] | 0.31 [−0.28, 0.91] |

| Years married | 0.14 [−0.1, 0.38] | 0.12 [−0.08, 0.31] | −0.29 [−0.53, −0.06] | 0.02 [−0.19, 0.23] | 0.01 [−0.27, 0.29] | −0.11 [−0.45, 0.24] |

| Health and well-being | ||||||

| Self-rated health | 0.05 [−0.15, 0.24] | −0.15 [−0.37, 0.07] | 0.29 [0.1, 0.47] | 0.11 [−0.09, 0.31] | −0.14 [−0.38, 0.09] | −0.2 [−0.61, 0.21] |

| Hospital frequency | 0.01 [−0.21, 0.22] | 0.25 [−0.01, 0.52] | −0.2 [−0.44, 0.04] | 0.11 [−0.14, 0.37] | −0.05 [−0.38, 0.28] | 0.25 [−0.28, 0.77] |

| Body mass index | 0.03 [−0.13, 0.2] | 0.13 [−0.02, 0.27] | −0.12 [−0.28, 0.05] | −0.06 [−0.24, 0.12] | 0.17 [−0.02, 0.37] | −0.02 [−0.23, 0.2] |

| Life satisfaction | 0.16 [−0.04, 0.35] | 0.09 [−0.1, 0.29] | 0.02 [−0.18, 0.22] | 0.13 [−0.07, 0.33] | −0.21 [−0.42, 0.01] | −0.31 [−0.6, −0.02] |

| Well-being | −0.42 [−1.32, 0.47] | −0.14 [−0.42, 0.13] | 1.11 [0.11, 2.12] | −0.31 [−1.04, 0.42] | −0.58 [−1.82, 0.65] | 0.1 [−0.36, 0.55] |

| Life events | ||||||

| Arrested for a crime | 0.33 [−0.13, 0.79] | −0.05 [−0.41, 0.31] | −0.12 [−0.6, 0.36] | 0.24 [−0.05, 0.54] | 0.07 [−0.41, 0.55] | −0.08 [−0.59, 0.42] |

| Beginning a serious relationship | 0 [−0.24, 0.24] | −0.17 [−0.42, 0.07] | 0.26 [0.03, 0.49] | 0.14 [−0.07, 0.35] | 0 [−0.26, 0.26] | −0.23 [−0.66, 0.2] |

| Breaking up with romantic partner | 0.06 [−0.19, 0.3] | −0.16 [−0.4, 0.07] | 0.19 [−0.04, 0.43] | 0.27 [0.07, 0.47] | −0.02 [−0.31, 0.26] | −0.16 [−0.58, 0.25] |

| Change careers | 0.08 [−0.17, 0.32] | 0.06 [−0.18, 0.3] | −0.11 [−0.35, 0.14] | 0.14 [−0.09, 0.37] | −0.07 [−0.36, 0.21] | 0.02 [−0.38, 0.41] |

| Change in closeness with parents and/or other family members | 0.08 [−0.17, 0.32] | 0.03 [−0.2, 0.27] | 0.03 [−0.21, 0.28] | 0.28 [0.07, 0.49] | 0.04 [−0.24, 0.32] | −0.29 [−0.73, 0.15] |

| Change of residence | 0.08 [−0.16, 0.32] | −0.07 [−0.3, 0.16] | −0.01 [−0.24, 0.22] | 0.19 [−0.02, 0.4] | −0.11 [−0.38, 0.16] | 0.07 [−0.31, 0.46] |

| Change place of employment | 0.02 [−0.23, 0.26] | 0.1 [−0.12, 0.32] | −0.09 [−0.31, 0.13] | 0.14 [−0.07, 0.36] | 0.16 [−0.1, 0.43] | −0.18 [−0.59, 0.23] |

| Death or serious illness/injury of a close family member or friend | 0.24 [0.01, 0.48] | 0.21 [−0.03, 0.45] | −0.42 [−0.66, −0.17] | 0.27 [0.02, 0.52] | 0 [−0.27, 0.26] | −0.05 [−0.41, 0.32] |

| Failing an important project | 0.18 [−0.11, 0.48] | −0.1 [−0.34, 0.15] | 0.06 [−0.23, 0.34] | 0.16 [−0.12, 0.43] | 0.32 [0, 0.64] | −0.39 [−0.88, 0.11] |

| Financial problems | 0.12 [−0.14, 0.37] | 0.03 [−0.21, 0.27] | −0.01 [−0.26, 0.25] | 0.36 [0.14, 0.58] | 0.16 [−0.14, 0.46] | −0.23 [−0.68, 0.22] |

| Fired from a job or serious trouble with employer | 0.12 [−0.16, 0.4] | −0.18 [−0.43, 0.07] | 0.01 [−0.27, 0.28] | 0.09 [−0.17, 0.34] | 0.17 [−0.16, 0.5] | −0.15 [−0.62, 0.32] |

| Got divorced | 0.24 [−0.06, 0.54] | −0.31 [−0.58, −0.05] | 0.19 [−0.08, 0.45] | 0.09 [−0.2, 0.37] | 0.01 [−0.3, 0.33] | −0.34 [−0.78, 0.1] |

| Got married | −0.14 [−0.36, 0.08] | −0.1 [−0.33, 0.14] | 0.27 [0.05, 0.5] | −0.04 [−0.25, 0.17] | 0.13 [−0.12, 0.39] | 0.1 [−0.28, 0.48] |

| Had children | −0.11 [−0.34, 0.13] | −0.01 [−0.23, 0.21] | 0.23 [−0.01, 0.46] | −0.16 [−0.39, 0.07] | −0.14 [−0.39, 0.1] | 0.22 [−0.16, 0.6] |

| Serious personal illness or injury | 0.11 [−0.14, 0.37] | −0.02 [−0.27, 0.23] | −0.07 [−0.33, 0.18] | 0.23 [0.01, 0.45] | −0.09 [−0.35, 0.18] | −0.06 [−0.46, 0.35] |

| Started a new job | 0.1 [−0.14, 0.35] | −0.02 [−0.23, 0.19] | −0.01 [−0.24, 0.22] | 0.05 [−0.16, 0.26] | −0.07 [−0.35, 0.21] | 0.02 [−0.34, 0.38] |

| Victim of a crime | 0.2 [−0.06, 0.47] | −0.21 [−0.47, 0.04] | −0.08 [−0.35, 0.19] | −0.01 [−0.25, 0.24] | 0.1 [−0.21, 0.41] | −0.65 [−1.08, −0.22] |

Note. Values in brackets are 95% confidence intervals. Selection effect: Narcissism facet at age 18 predicted the individual life experience or event. Socialization effect: The individual life experience or event predicted change in the narcissism facet from age 18 and age 41.

Which Life Events and Experiences are Associated with Changes in Narcissism? - Socialization Effects

An examination of the putative socialization effects of life events and experiences on changes in narcissism is predicated on the existence of individual differences in the way individuals changed over time, which we found for overall narcissism, leadership, and vanity. That is, while many participants declined in narcissism, a few increased and others showed little or no change from young adulthood to middle age. Thus, we now turn to our analyses exploring whether life events and life experiences were related to individual differences in change in narcissism over time. We will only report results for overall narcissism, leadership, and vanity because the entitlement facet did not show significant variance in the latent change variable. Interestingly, many of the notable associations between life experiences and change in narcissism involved the vanity facet.

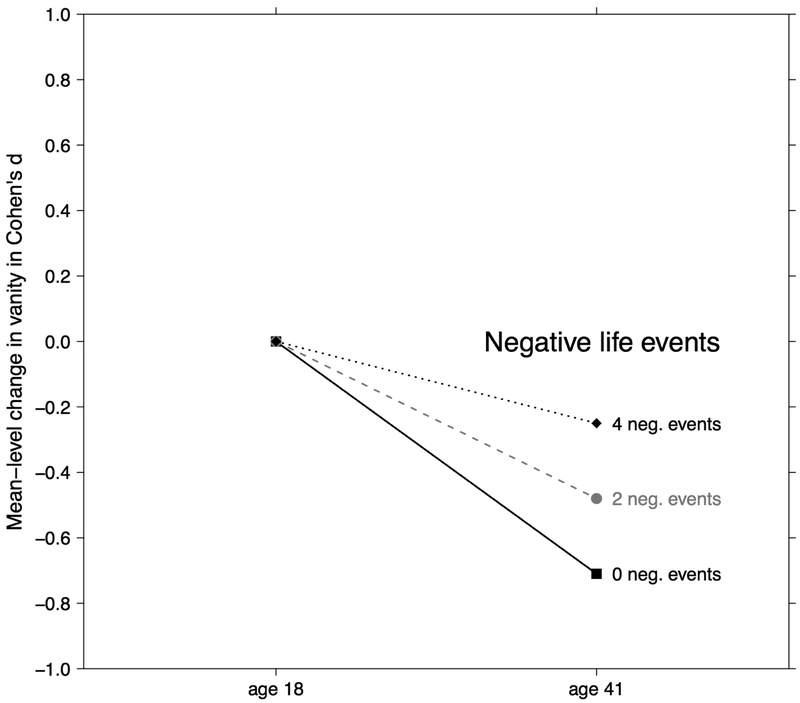

In terms of positive and negative life events, experiencing more negative life events was associated positively with changes in vanity (β = 0.21, 95% CI = [0.06, 0.36]). As Figure 3 shows, this means that individuals who had more negative life events did not decrease as much on vanity as the average person in the sample between ages 18 and 41. For example, participants who had experienced four negative life events (two more than the average person) decreased by about one-quarter standard deviation on vanity (d = −0.25), compared to the one-half standard deviation (d = −0.48) drop observed for people who experienced two negative life events. The number of agentic or communal life events did not predict changes in overall narcissism.

Figure 3.

Mean-level decreases (d) in vanity for participants with an average number of negative life events (2) and 1 SD below (0) and 1 SD above (4) the mean. This depiction assumes that the number of positive life events is held constant at the average. The mean was fixed to 0 at age 18 for identification.

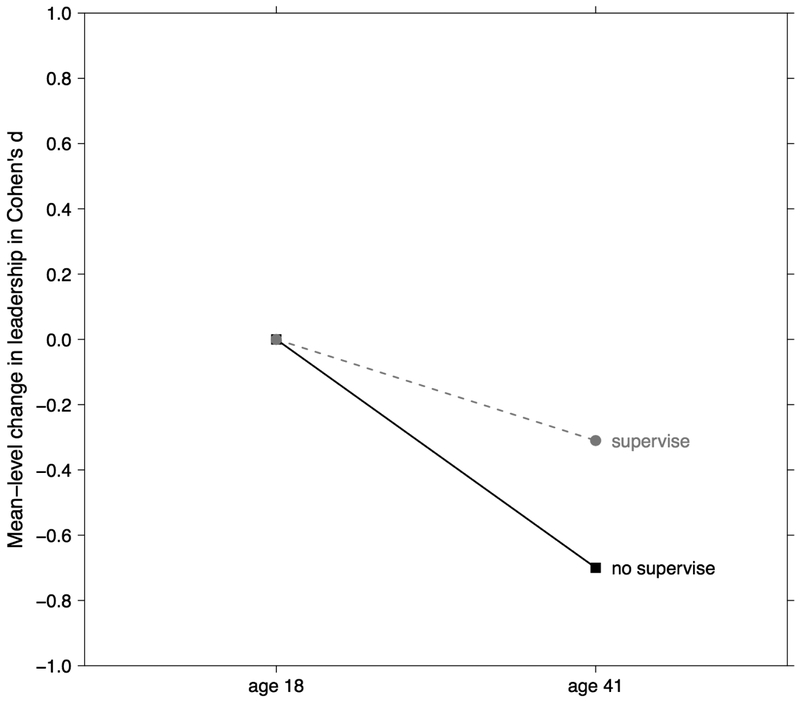

Supervising people, being able to fire employees, and handling a budget at work were positively associated with changes in overall narcissism and leadership (see Table 4). As Figure 4 shows, this did not mean that people who had more power at work increased in narcissism, but rather that they failed to decrease as much as was normative. Also, participants who worked in realistic jobs experienced a stronger decrease in overall narcissism (β = −0.22, 95% CI = [−0.39, −0.05]), while those who worked in enterprising jobs experienced smaller decreases in the leadership facet (β = 0.19, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.35]). Financial problems were associated with smaller decreases in overall narcissism (β = 0.25, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.46]) and vanity (β = 0.33, 95% CI = [0.11, 0.55]). Many work experiences were unrelated to changes in narcissism, including salary, job prestige, and job satisfaction.

Figure 4.

Mean-level decreases (d) in the leadership facet for participants who supervise others at work versus do not supervise others at work. The mean was fixed to 0 at age 18 for identification.

There were fewer associations between relationship experiences and changes in either overall narcissism or its facets. Four associations stood out as notable. First, being in a serious relationship was associated with a larger decrease in vanity (β = −0.25, 95% CI = [−0.49, − 0.01]). Second, breaking up with a romantic partner was associated with a smaller decrease in vanity (β = 0.28, 95% CI = [0.08, 0.49]). Third, change in closeness with family was also associated with a smaller decrease in vanity (β = 0.25, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.46]). Fourth, having children was associated with a larger decrease in vanity (β = −0.15, 95% CI = [−0.37, 0.08]. In contrast to the observed selection effects, relationship satisfaction, number of children, and experiencing divorce were not related to changes in overall narcissism or its facets.

In terms of health and well-being, higher self-rated health was nominally related to a smaller decrease in vanity (β = 0.13, 95% CI = [−0.06, 0.32]) as was life satisfaction (β = 0.14, 95% CI = [−0.03, 0.30]). Experiencing a serious personal illness or injury was associated with a smaller decrease in vanity also (β = 0.24, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.47]). Similarly, the death or serious illness of a family member was also positively associated with change in vanity (β = 0.25, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.47])7,8.

The same socialization effects were generally found when the facets were modeled simultaneously (see Table 5), but there were a few differences. In the work domain, being in a realistic (β = −0.24, 95% CI = [−0.42, −0.07]) or investigative β = −0.19, 95% CI = [−0.37, − 0.02]) job became related to stronger decreases in leadership. In the health-domain, self-rated health no longer predicted changes in vanity.

Summary of results

In summary, we found that narcissism and its facets decreased from age 18 to age 41. These decreases in narcissism serve as the backdrop to the selection and socialization patterns we discovered. In particular, overall narcissism and the leadership facet were associated with jobs that involved more control over others. Vanity was the best predictor of relationships and health experiences. Similarly, most socialization associations involved the vanity facet.

Discussion

This study is the first long-term longitudinal study investigating rank-order consistency and change in narcissism and three narcissism facets from young adulthood to middle age. In addition, we investigated whether young adult narcissism predicted subsequent life events and experiences and whether life events and experiences were related to changes in narcissism from young adulthood to midlife.

Rank-order consistency and Change in Narcissism

We found that overall narcissism and its facets showed high levels of rank-order consistency that were similar to the rank-order consistencies reported for the Big Five (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000) and self-esteem (Trzesniewski, Donnellan, & Robins, 2003) during this stage of life. Thus, people who are high on narcissism relative to others tend to maintain their standing. Of the narcissism facets, vanity showed the weakest rank-order consistency while entitlement showed the strongest rank-order consistency.

In line with our hypotheses (H1, H2a, and H2b), we found moderate to large mean-level decreases in overall narcissism, vanity, and entitlement. These findings are consistent with the maturity principle of personality development (Roberts et al., 2006). As young adults grow older, they become less self-focused and more prosocial in nature. However, our hypothesis that people would show an increase in the leadership facet (H2c) was not supported; instead, we found a moderate decrease. One possible reason for this finding is the nature of the dominance captured in the NPI leadership facet. The NPI’s leadership items mostly address aspects of exercising power over others and possessing a motivation to lead, such as item 27a (I have a strong will to power.) and item 36a (I am a born leader.). There are fewer items that address prosocial and neutral forms of assertiveness (e.g., item 11a: I am assertive.), which is the component (i.e., social dominance) that past research has shown tends to increase (Roberts et al. 2006), and thus drove our expectation of an increase in the leadership facet.

Individual Differences in Changes in Narcissism: Selection and Socialization Effects

The current study also examined the selection and socialization patterns associated with being narcissistic. These analyses focused on the occurrence of positive and negative events, agentic and communal events, as well as a more targeted examination of narcissists’ specific work, relationship, and health outcomes.

Selection Effects.

More entitled participants tended to experience more negative life events. Our hypotheses that more narcissistic participants would experience more agentic (H3) and fewer communal (H4) life events were not confirmed.

College students who were more narcissistic or who saw themselves as an ideal leader (leadership facet), tended to be in jobs that afforded them more opportunity to control subordinates through supervising or hiring decisions. Given the interpersonal difficulties that narcissists create for themselves (Paulhus, 1998), as well as their propensity to engage in selfish and unethical behavior (Brunell, Staats, Barden, & Hupp, 2011; Campbell, Bush, Brunell, & Shelton, 2005) and risk-taking (Chatterjee & Hambrick, 2007), the fact that narcissists end up in powerful positions that control the material resources and potentially even the well-being of their subordinates deserves greater attention in organizational research. Past work in the organizational domain had established that narcissists are more likely to emerge as leaders in small groups (Grijalva, Harms, Newman, Gaddis, & Fraley, 2015), but most of this research has been conducted in lab settings where students engage in leaderless group discussions and then report who emerges as the group’s leader. Our study, on the other hand, followed students over time to observe who actually obtains leadership positions in organizations. Selection processes may inadvertently reward these people with positions that then cause difficulty for others.

In terms of family structure and health, the vanity facet had both negative and positive associations with life paths from young adulthood to midlife. In particular, those who were higher on vanity in college were prone to unstable relationships and marriages, were more likely to divorce, and were less likely to stay in relationships as long as their peers. These findings fit with previous research indicating that people high on narcissism tend to be less committed in intimate relationships (Campbell & Foster, 2002; Foster et al., 2006). Lower investment in close relationships is also consistent with past research establishing that narcissists are low in communion (Campbell & Foster, 2007). Perhaps as a result of their less stable relationships, these same individuals tended to have fewer children by midlife. On the more positive side of the equation, vainer college students tended to report better health for themselves. In contrast, those who were more entitled tended to have lower well-being and life satisfaction.

Our selection effects thus confirm previous findings indicating that some narcissism facets such as entitlement appear to be maladaptive while others such as leadership appear to be adaptive (Rhodewalt & Morf, 1995; Sedikides et al., 2004).

Socialization Effects.