The current novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) infection is rapidly spreading worldwide. The dissemination of the virus has been particularly severe in the Northern part of Italy (Lombardia region).

Currently, we had the opportunity to study the cutaneous histopathological features of eight COVID-19 patients in different stages and with several degrees of disease. The histopathology of the skin specimens suggested a broad spectrum of cutaneous features that can all be linked to the COVID-19 interplay with the skin.

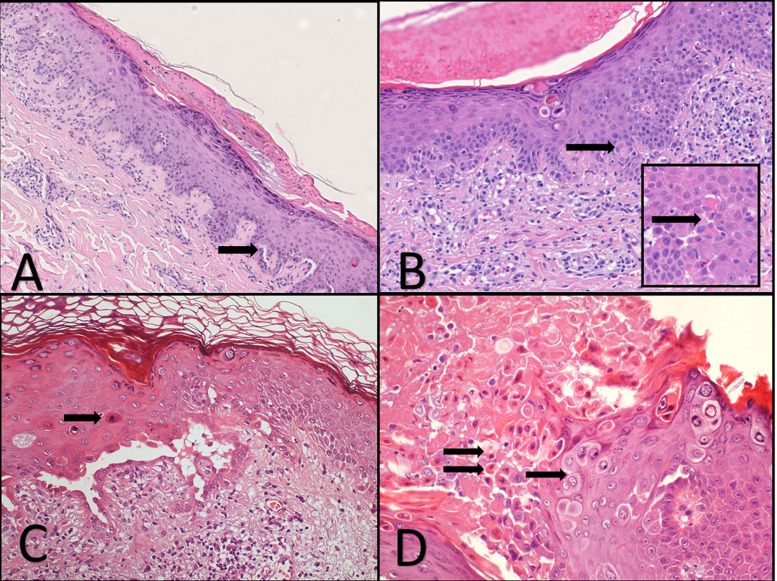

Interestingly, we observed two COVID-19 patients who encountered only fever, sore throat, and cough a sudden diffuse maculopapular eruption involving only the trunk, clinically suggestive for Grover disease (Fig. 1 F). Histopathology showed, in addition to the classic dyskeratotic cells, ballooning multinucleated cells and sparse necrotic keratinocytes with lymphocytic satellitosis (Fig. 2 A–D). These overlapping features mimicking a viral infection and Grover disease have already been described in patients with simultaneous Grover and Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption [2,3]. At the time of the onset of their cutaneous eruption, these patients were also on no new drug treatment. The others developed cutaneous lesions during hospitalization and were treated with levofloxacin and hydroxychloroquine that are not recognized to cause a diffuse lymphocytic vasculitis with microthrombi formation.

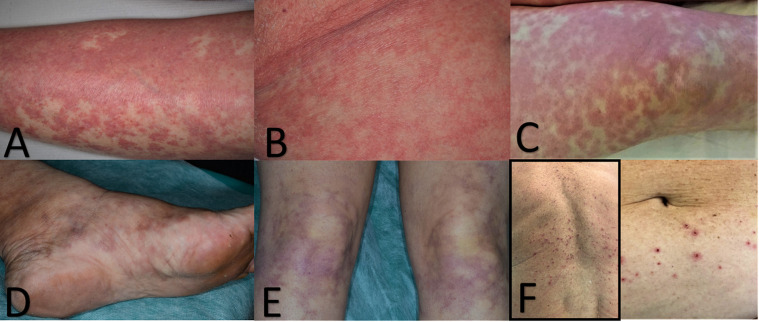

Fig. 1.

A) Diffuse maculo-papulo-vesicular rash. Hemorragic dot-like area are due to extravasated erytrhocytes. B) Sligthly papular erythematous exanthema of the trunk. C) Diffuse macular livedoid hemorrhagic lesions in a patient with CID like histopathological feature. (D &E) Initial resolution of the lesions after therapy. (F) Erythematous papular eruption with crusted and erosive lesions mimicking Grover disease.

Fig. 2.

A) Parakeratosis, acanthosis, dyskeratotic keratinocytes and small acantholytic cleft (arrow). B) Dyskeratotic keratinocytes in the upper part of the epidermis. Necrotic keratinocytes (arrow). Inset, Necrotic keratinocytes with lymphocytes satellitosis (arrow). C Necrotic keratinocytes (arrow) and more prominent acantholytic cleft. D) Necrotic keratinocytes (double arrows) and pseudo-herpetic features (arrow).

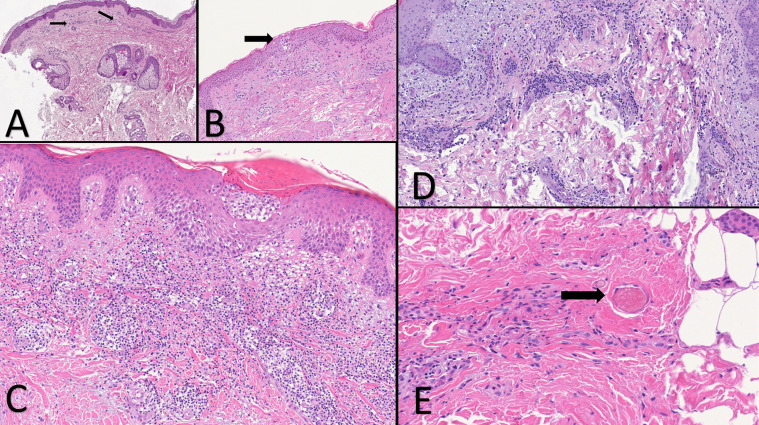

An hospitalized patient was biopsied at early stage of a exanthema involving the trunk and limbs. The first punch biopsy showed in the upper dermis diffuse telangiectatic small blood vessels with no other peculiar features (Fig. 3 A). In a second punch nests of Langerhans cells within the epidermis was the unique clue in this stage (Fig. 3B). When purpuric maculo-papulo-vesicular rash was developed (Fig. 1A), histological findings showed a perivascular spongiotic dermatitis with exocytosis along with a large nest of Langerhans cells and a dense perivascular lymphocytic infiltration eosinophilic rich around the swollen blood vessels with extravasated erythrocytes (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

A) Initial phase of the exantematous rash. Merely teleangectatic blood vessels (arrows) B) Exanthematous rash biopsied three days after the onset. A small nest of Langerhans cell within the epidermis (arrow). Mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in the superficial dermis. C) A papulo-vesicular lesion. Spongiosis, a large intraepidermal nest of Langerhans cell. D) Maculo-papular exanthema. E) Haemorragic diffuse exanthematous rash. A small thrombus in a capillary vessel (arrow).

Specimen from a hospitalized old man with papular erythematous exanthema involving trunk (Fig. 1B) showed edematous dermis with many eosinophils. Cuffs of lymphocytes around blood vessels in a lymphocytic vasculitis histopathological pattern were observed (Fig. 3D).

Hospitalized patient in ICU had a severe macular haemorrhagic eruption (Fig. 1C–E), which corresponds to intravascular microthrombi in the small dermal vessels (Fig. 3E). Autopsy records from SARS-CoV-2 infected patients reported this element in the lung and skin microvessels [1].

Among skin pathologies in which a virus is implicated, we can see various types of manifestations in the cutaneous district involved. Frequently, it is merely an exanthema indicating a hematogenous spreading of the virus through the cutaneous vascular system. The next step could create activation of the immune system with mobilization of lymphocytes and Langerhans cells patrolling that run through the skin-lymph node path. If the virus swarm induces the creation of immune complexes, this can lead CD4 + T helper lymphocytes to produce cytokines, like IL-1, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, and to recruit eosinophils, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, B cells and natural killer (NK) cells leading a lymphocytic thrombophilic arteritis [4]. Sepsis or severe viral infections could activate the cytokine cascade inducing a CID phenomenon [5]. Just like we observed in the skin and in the lung and kidneys of COVID + patients. However, there are underhanded viral attacks that probably induce a modification in the structure of the keratinocyte, which is destroyed by the cytotoxic lymphocytes, almost resembling the well- known ancient trick of the "Trojan horse." In lichen striatus, a viral alteration of the keratinocyte clones along the Blaschko's lines has been hypothesized [[6], [7], [8]]. In fact, in its classic form, it can be observed histologically a band like dermatitis with lymphocyte satellitosis destroying the keratinocytes. Also, here we have the presence of Langerhans nests. Ultimately, the HSV is suspected of provoking stimulation of immunopathological mechanisms in erythema multiforme. The herpes virus could play a role in autoimmune cross-reactivity [9], triggering the keratinocyte that activates IL-1, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, recruiting cytotoxic and NK cells that target the keratinocytes itself. Histopathological examination of lung biopsy of COVID + pneumonia indicates a severe damage of the alveolar epithelial cell floating in the alveolar space just like in bullous severe erythema multiforme in which ballooning keratinocytes detach from the spinous layer [10].

In 1955, Ferdinando Gianotti, father of first author, published as a single author, the first observation of unusual dermatitis, which later became known as “Gianotti-Crosti disease” [11]. Langerhans’ nests were present along with a scattered perivascular and lymphocytic infiltrate that was slightly more epidermotropic than the recently reviewed cases of the two patients with a rash.

We think that different clinical features of skin eruption in patients with COVID infection reflect a full spectrum of viral interaction with the skin. Further histopathological studies and PCR investigation on skin biopsies are necessary to clarify the close relationship between skin and SARS-CoV-2 infection.

References

- 1.Magro C., Mulvey J.J., Berlin D., Nuovo G., Salvatore S., Harp J., Baxter-Stoltzfus A., Laurence J. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID -19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capusan T.M., Herrero-Moyano M., Fraga J., Llamas-Velasco M. Clinico-pathological study of 4 cases of pseudoherpetic grover disease: the same as vesicular grover disease. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2018;40:445–448. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000001058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kosann M.K., Fogelman J.P., Stern R.L. Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption in a patient with Grover's disease. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2003;49:914–915. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)00854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee J.S., Kossard S., McGrath M.A. Lymphocytic thrombophilic arteritis: a newly described medium-sized vessel arteritis of the skin. Arch. Dermatol. 2008;144:1175–1182. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levi M. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2018;40:115–120. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gianotti R., Restano L., Grimalt R., Berti E., Alessi E., Caputo J. Lichen striatus--a chameleon: an histopathological and immunohistological study of forty-one cases. J. Cutan. Pathol. 1995;22:18–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1995.tb00734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hafner C., Landthaler M., Vogt T. Lichen striatus (blaschkitis) following varicella infection. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2006;20:1345–1347. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones J., Marquart J.D., Logemann N.F., DiBlasi D.R. Lichen striatus-like eruption in an adult following hepatitis B vaccination: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol. Online J. 2018;24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lucchese A. From HSV infection to erythema multiforme through autoimmune crossreactivity. Autoimmun. Rev. 2018;17:576–581. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yao X.H., Li T.Y., He Z.C. A pathological report of three COVID-19 cases by minimally invasive autopsies. Zhonghua. Bing. Li. Xue. Za. Zhi. 2020;15(49) doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112151-20200312-00193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandt O., Abeck D., Gianotti R., Burgdorf W. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2006;54:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]