Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). It has infected millions, with more than 275,000 fatal cases as of May 8, 2020. Currently, there are no specific COVID-19 therapies. Most patients depend on mechanical ventilation. Current COVID-19 data clearly highlight that cytokine storm and activated immune cell migration to the lungs characterize the early immune response to COVID-19 that causes severe lung damage and development of acute respiratory distress syndrome. In view of uncertainty associated with immunosuppressive treatments, such as corticosteroids and their possible secondary effects, including risks of secondary infections, we suggest immunotherapies as an adjunct therapy in severe COVID-19 cases. Such immunotherapies based on inflammatory cytokine neutralization, immunomodulation, and passive viral neutralization not only reduce inflammation, inflammation-associated lung damage, or viral load but could also prevent intensive care unit hospitalization and dependency on mechanical ventilation, both of which are limited resources.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, cytokine storm syndrome, immunotherapy, cytokines, monoclonal antibody, inflammation, passive immunotherapy, IVIG, convalescent plasma, hyperimmune globulin

Graphical Abstract

An overreactive immune response, cytokine storm, and development of acute respiratory distress syndrome characterize severe cases of COVID-19. Bonam et al. present a Perspective on diverse immunotherapeutic approaches based on the neutralization of inflammatory cytokines, immunomodulation, and passive viral neutralization for treating severely ill COVID-19 patients.

Main Text

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” (SARS-CoV-2). It has affected over 3.95 million people, with more than 275,000 fatal cases as of 8th May 2020 (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html). Although the majority of cases result in mild symptoms, such as fever and cough, about 10%–15% progress to severe pneumonia and respiratory failure, requiring intensive care unit (ICU) hospitalization and mechanical ventilation. The death rate in ICU-admitted patients could reach up to 26%. Age and other health problems, such as chronic pulmonary or cardiac disease conditions, are the risk factors that determine the mortality rate.4, 2, 1, 3 A systematic review and meta-analysis confirmed that old age and/or associated comorbidity are the common risk factors that predict death in all three major respiratory diseases caused by coronaviruses, including COVID-19, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS).5 Obesity is another risk factor for the development of severe SARS-CoV-2.6 Though anti-viral molecules and hydroxychloroquine are under investigation to avert severe disease,7, 8, 9, 10, 11 currently, there are no specific therapies for COVID-19, particularly when severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) occurs. Most COVID-19 patients with ARDS required ICU hospitalization and prolonged supportive mechanical ventilator management.1,2,4 ARDS can lead to other complications, including secondary bacterial infection and lung fibrosis.

Inflammatory Response to COVID-19

Recent clinical data suggest that severe COVID-19 is due to an overreactive immune response leading to a cytokine storm and development of ARDS.12,13 Plasma obtained from COVID-19 patients, in particular moribund patients, demonstrated increased concentrations of various inflammation-related cytokines and chemokines implicated in the recruitment of immune cells, including interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-17, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interferon (IFN)-γ, C-X-C motif chemokine 10 (CXCL10), chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), CCL3, and CCL4.1,14,15 In addition, COVID-19 patients showed relatively increased neutrophil counts in the blood.15 On the other hand, monocytes, basophils, and T cells, especially CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, were decreased in the peripheral blood, possibly due to their migration to the lungs.13, 14, 15, 16, 17 However, these T cells exhibited enhanced activated markers (CD69, CD38, and CD44).17

Single-cell RNA sequencing of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid immune cells from a small number of mild to severely ill COVID-19 patients suggested that balance in the lung macrophage populations is highly dysregulated in severely ill COVID-19 patients. These data indicate that monocyte-derived macrophages (FCN1+) rather than FABP4+ alveolar macrophages contribute to lung inflammation and lung damage in severe cases.18 This study thus confirms another report based on lung post mortem biopsy of a patient that revealed the presence of bilateral diffuse alveolar damage and recruitment of monocytes.13 The study by Liao et al.18 also observed an increased proportion of clonally expanded CD8+ T cells in the BAL fluid of mild cases as compared to severe cases. Another investigation that compared BAL fluid immune cells in various respiratory pathologies highlighted a more prominent surge of neutrophils in COVID-19 patients as compared to pneumonia caused by other pathogens.19 By metatranscriptome sequencing of BAL fluid and global functional analyses of differentially expressed genes, this report also identified strong upregulation of numerous type I IFN-inducible genes.19

However, caution needs to be exercised while interpreting these data due to potential influence of therapies, such as IFNα-2b, anti-virals, and/or steroids on the landscape of immune cells and immune signatures of BAL fluid or lungs. Nevertheless, these reports confirm the proposition that an influx of immune cells to the lungs follows SARS-CoV-2 infection (Figure 1).

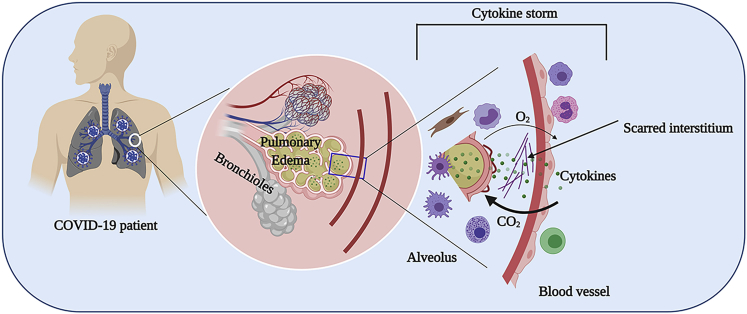

Figure 1.

Cytokine Storm in COVID-19 Infection

Lungs are the primary organs affected by SARS-CoV-2. A dysregulated cytokine response (i.e., cytokine storm) due to an influx of activated immune cells following SARS-CoV-2 infection results in pulmonary edema, leading to damaged alveoli and formation of scarred interstitium culminating in a reduced gas exchange process. The figure was created with the support of https://biorender.com under the paid subscription.

Severely ill COVID-19 patients also displayed reduced peripheral blood regulatory T cells (T-reg cells), the immune suppressor cells critical for reducing inflammation and inflammation-associated tissue damage.15 Another report suggested that activated GM-CSF+IFNγ+ pathogenic Th1 cells that secrete GM-CSF promote inflammatory CD14+CD16+ monocyte responses with enhanced IL-6.17 GM-CSF+IFNγ+ Th1 cells and inflammatory monocytes were positively correlated with the severe pulmonary syndrome characteristic of COVID-19 patients.17 The simultaneous increase in IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) and IL-10 also suggest that anti-inflammatory responses, though induced, are not sufficient to reduce inflammation and eventually lead to severe lung damage.

Biomarkers That Could Predict ARDS in COVID-19 Patients

Various reports have shown that higher inflammation-related biomarkers, such as plasma C-reactive protein (CRP), ferritin, and IL-6, were significantly associated with higher risks of developing ARDS.20, 21, 22, 23, 24 Of note, IL-6 levels were associated with course of the disease and death from COVID-19.20,23,24

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 30 studies conducted in China (26 studies, of which 13 are from Wuhan), Australia, USA, and Korea that included 53,000 patients with COVID-19 has confirmed that raised CRP (41.12–67.62 mg/L in severe versus 12.00–21.48 in mild cases) and ferritin (654.26–2,087.63 ng/mL versus 43.01–1,005.97) are found in seriously ill COVID-19 patients.5 The massive increase in plasma ferritin levels is indicative of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis activation syndrome in these patients. These studies thus provide a rationale for targeting inflammatory mediators for the management of severely ill COVID-19 patients.

The Use of Corticosteroids in COVID-19 Patients

Currently, there is no clear evidence for the use of steroids in SARS-CoV-2 infections, and their use is highly debated, particularly with respect to the window of treatment, dose, and management of patients in cases of bacterial co-infection. A retrospective cohort analysis of 201 patients from Wuhan suggested that methylprednisolone might benefit patients who develop ARDS (n = 88) by reducing the death rate.20 A retrospective analysis of hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia (n = 46) indicated that an early low-dose steroid therapy (1–2 mg/kg/day) in 26 patients for a short duration (5–7 days) reduced the oxygen requirement period and improved disease course.25

However, COVID-19 patients treated with methylprednisolone were sicker and had a higher pneumonia severity index than those patients who did not receive methylprednisolone.20 Recently, an additional retrospective matched case-control study involving 31 paired patients in several ICUs in China showed that treatment with steroids for 8 days (4–12 days) in addition to anti-viral drugs was associated with a 39% 28-day death rate, compared to 16% in a propensity score matched control group.26 Clinical evidence is also lacking for the use of steroids in other coronavirus diseases (SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV),27,28 and steroids might even impair viral clearance mechanisms of patients and predispose them to secondary infections. Double-blinded randomized clinical trials involving a large number of patients should be conducted to evaluate the use of steroids in severely ill COVID-19 patients with reduction in ICU requirement as the primary endpoint.

Therefore, as per World Health Organization (WHO) interim guidance of March 13, 2020,29 and some local guidelines (https://covidprotocols.org),30 steroids are not recommended at present as a treatment for COVID-19. If steroids are used for a particular pathological condition, low dose and short duration of treatment are recommended. Similarly, as per a survey from the French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety (ANSM), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen are also not recommended, due to infectious complications and kidney, cardiac, and gastrointestinal adverse effects.31

In view of an uncertain prognosis and complications due to generalized immunosuppression from corticosteroid and NSAID treatment, immunotherapies based on immunomodulatory approaches appear promising in the treatment of COVID-19 to regulate inflammation and anti-viral immune responses. We believe that the immunotherapies discussed next could result in a quicker therapeutic response with minimal adverse effects.

Immunotherapies as an Adjunct to COVID-19 Patient Management

The current clinical data on COVID-19 patients clearly highlight that cytokine storm and an influx of activated immune cells to the lungs characterize the early immune response to COVID-19 that causes severe lung damage. Therefore, we suggest host-directed immunotherapies as an adjunct therapy in severe cases to not only reduce inflammation and inflammation-associated lung damage but also to prevent ICU hospitalization and dependency on mechanical ventilation that are limited resources in the context of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. In fact, several immunotherapeutic approaches that target either inflammatory mediators, passively neutralize SARS-CoV-2, or prevent viral entry are under evaluation at various centers (Table 1; Figure 2), thus giving perfect examples of such drug repurposing. In addition, lessons learned from the management of other severe respiratory diseases, as in the case of SARS, MERS, and severe influenza, provide a roadmap for tackling ARDS and cytokine storm in severely ill COVID-19 patients.27,32,33

Table 1.

Immunotherapies under Evaluation for COVID-19

| Immunomodulator/Organizationa | Mechanism | Stage of development | Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anakinra/Swedish Orphan Biovitrum | IL-1 receptor antagonist | Phase 3 | NCT04324021 |

| Anakinra/Hellenic Institute for the Study of Sepsis | Phase 2 | NCT04339712 | |

| Anakinra/Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris | Phase 2 | NCT04341584 | |

| Anakinra/University Hospital, Ghent | Phase 3 | NCT04330638 | |

| Baricitinib/Lisa Barrett | TNF inhibitor | Phase 2 | NCT04321993 |

| Baricitinib/Hospital of Prato | Phase 3 | NCT04320277 | |

| TJ003234 (Anti-GM-CSF Monoclonal Antibody)/ I-Mab Biopharma Co. Ltd | GM-CSF neutralization | Phase 1b/2 | NCT04341116 |

| Bevacizumab/Qilu Hospital of Shandong University | Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor | Phase 3 | NCT04275414, NCT04305106 |

| CD24Fc/OncoImmune, Inc. | Regulation of innate response to inflammatory stimuli and tissue injury by binding to danger-associated molecular patterns and Siglec G/10 | Phase 3 | NCT04317040 |

| Eculizumab (Soliris)/Hudson Medical | Inhibition of complement activation by binding to terminal complement protein C5 | NA | NCT04288713 |

| Emapalumab/Swedish Orphan Biovitrum | Blockade of IFN-γ mediated signaling pathways | Phase 2 | NCT04324021 |

| Fingolimod (FTY720)/First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University | Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor regulator | Phase 2 | NCT04280588 |

| Interferon β1α/Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, France | Inhibition of viral replication by inducing type I IFN-stimulated genes | Phase 3 | NCT04315948 |

| Recombinant human interferon α1β/Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine | Phase 3 | NCT04320238 | |

| Recombinant human interferon α2β/Tongji Hospital | Early Phase 1 | NCT04293887 | |

| Meplazumab/Tang-Du Hospital | Prevention of CD147-mediated SARS-CoV-2 viral entry and T cell chemotaxis | Phase 2 | NCT04275245 |

| Siltuximab/University Hospital, Ghent | IL-6 neutralization | Phase 3 | NCT04330638 |

| Sarilumab/Regeneron Pharmaceuticals | IL-6 receptor antagonist | Phase 2 | NCT04315298 |

| Sarilumab/Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris | Phase 2/3 | NCT04324073 | |

| Sarilumab/Sanofi | Phase 2/3 | NCT04327388 | |

| Sarilumab/Nova Scotia Health Authority | Phase 2 | NCT04321993 | |

| Tocilizumab/National Cancer Institute, Naples | Phase 2 | NCT04317092 | |

| Tocilizumab/Hoffmann-La Roche | Phase 3 | NCT04320615 | |

| Tocilizumab/University of L'Aquila | NA | NCT04332913 | |

| Tocilizumab/University Hospital, Ghent | Phase 3 | NCT04330638 | |

| RoActemra or Kevzara/Marius Henriksen | Phase 2 | NCT04322773 | |

| Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG)/Peking Union Medical College Hospital | Suppression of innate and adaptive inflammatory responses and concomitant enhancement of anti-inflammatory processes. | Phase 2/3 | NCT04261426 |

| Immunoglobulin from cured patients/Wuhan Union Hospital, China | Virus neutralization | NA | NCT04264858 |

| Anti-SARS-CoV-2 inactivated convalescent plasma/Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center | NA | NCT04292340 | |

| Human coronavirus immune plasma /Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins | Phase 2 | NCT04323800 | |

| Convalescent plasma/Mayo Clinic | Phase 2 | NCT04325672 | |

| Hyperimmune plasma/Foundation IRCCS San Matteo Hospital | NA | NCT04321421 | |

| Convalescent plasma/Baylor Research Institute | Phase 1 | NCT04333251 | |

| Convalescent plasma/Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Iran | NA | NCT04327349 | |

| Convalescent plasma/Universidad del Rosario, Colombia | Phase 2/3 | NCT04332835 | |

| Convalescent plasma/Universidad del Rosario, Colombi | Phase 2 | NCT04332380 | |

| NK cell treatment/Xinxiang medical university | Anti-viral action | Phase 1 | NCT04280224 |

| NKG2D-ACE2 CAR-NK Cells/Chongqing Public Health Medical Center | GM-CSF neutralization, CRS prevention, inhibition of viral infection of alveolar epithelial cells and clearance of virus-infected cells | Phase 1/2 | NCT04324996 |

NA, not applicable

The drugs tabulated here are included in clinical trials (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) either alone or in combination with other drugs/supplements.

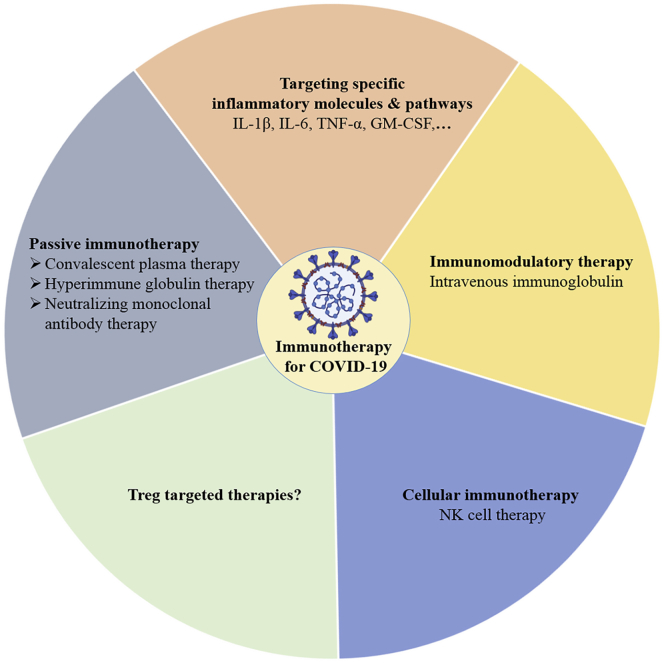

Figure 2.

Immunotherapeutic Strategies for Severely Ill COVID-19 Patients

Diversified immunotherapeutic approaches against severe COVID-19 cases are illustrated. The figure was created with the support of https://biorender.com under the paid subscription.

Immunotherapies that Target Specific Inflammatory Molecules and Pathways

An increase in IL-6 leading to lung tissue damage has been observed in a majority of the COVID-19 patients.13,14,16,17 Of note, similar to severely ill COVID-19 cases, elevated serum levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ have been consistently observed in cytokine release syndrome (CRS) that is common in the patients receiving T-cell-engaging immunotherapies (bispecific antibody constructs or chimeric antigen receptor [CAR] T cell therapies).34 Targeting either IL-6 (siltuximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody) or IL-6 receptor (tocilizumab, a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody) led to rapid resolution of CRS symptoms in those patients.34 Severe CRS can also lead to hypotension, pulmonary edema, and cardiac dysfunction that are commonly observed in severely ill COVID-19 patients. These data provide justification for targeting IL-6 in severely ill COVID-19 patients.

Both anti-IL-6 receptor antibodies (tocilizumab and a human monoclonal antibody sarilumab [Kevzara]) and anti-IL-6 antibody siltuximab (Sylvant) are under evaluation in COVID-19 patients at various centers (Table 1). An immunosuppressed patient with severe COVID-19-related lung disease was successfully treated with tocilizumab, and therapy led to a partial decrease in the pulmonary infiltrates.35 Unpublished data based on off-label use of tocilizumab along with lopinavir and methylprednisolone in 21 severely ill COVID-19 patients suggested that the addition of tocilizumab not only quickly reduced their clinical symptoms (fever and oxygen requirement) and inflammation but also normalized peripheral blood T cell counts in the majority of patients.36 Further, a recent unpublished randomized trial from French investigators that involved 129 patients with moderate or severe COVID pneumonia suggested that tocilizumab significantly improves the prognosis of these patients. Further details of this trial are awaited (https://www.aphp.fr/contenu/le-tocilizumab-ameliore-significativement-le-pronostic-des-patients-avec-pneumonie-covid).

Additional targets include TNF-α (infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody to TNF-α; etanercept, a recombinant fusion TNF-R that binds soluble TNF-α) and IFN-γ (emapalumab, a fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibody against IFN-γ; Table 1). Of note, clinical trials in idiopathic pneumonia syndrome have reported favorable response to etanercept therapy.37,38

GM-CSF represents another target for severe cases of COVID-19. GM-CSF stimulates the influx of granulocytes and monocytes from bone marrow and hence further enhances inflammatory responses. A randomized phase 1b/2, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial is currently recruiting patients to investigate the therapeutic efficacy of a humanized anti-GM-CSF IgG1 monoclonal antibody TJ003234 in severely ill COVID-19 patients (NCT04341116). In addition, another human monoclonal antibody that targets GM-CSF (gimsilumab; Roivant Sciences, Altasciences) is under consideration for treating ARDS in COVID-19 patients.39,40

Likewise, baricitinib, a selective Janus kinase (JAK1/JAK2) inhibitor, inhibits gp130 family cytokines (such as IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, and IFN-γ).41 In addition, baricitinib inhibits the AP2-associated protein kinase 1 and cyclin-G-associated kinases that are regulators of viral endocytosis process and hence could block viral infection of cells.41 Similarly, anakinra (Kineret), a recombinant human IL-1RA, and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved JAK2 inhibitor fedratinib (Inrebic) also possess the capacity to suppress inflammation (Table 1).42 Though JAK inhibitors can impair type-I-IFN-mediated anti-viral responses, recent data from metatranscriptome sequencing of BAL fluid from eight COVID-19 patients highlight that SARS-CoV-2 induces strong type I IFN responses with an overexpression of a large number of type I IFN-inducible genes implicated in inflammation.19 Therefore, use of JAK inhibitors might help in alleviating inflammation, but dose and window of treatment should be tailored to ensure that anti-viral response of the patient is not totally curtailed.

Type I IFN (β1α and β2α) is under consideration for severe COVID-19 (Table 1). Type I IFN signals through JAK-STAT (signal transducers and activators of transcription) pathway and upregulates IFN-stimulated genes that kill viruses in the infected cells. Our knowledge on the role of type I IFN in the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infection is not complete. Current evidence, however, reveals an overexpression of a large number of type-I-IFN-inducible genes with immunopathogenic potentials in COVID-19 patients.19 Also, results on the use of IFN-α in SARS patients are inconclusive.27 Therefore, care should be taken regarding the dosage of type I IFN and timing of treatment to avoid deleterious effects.

Intravenous Immunoglobulin Therapy

Additional immunotherapies that could be considered for COVID-19 include immunomodulators that have broad anti-inflammatory effects, such as pooled normal immunoglobulin G (IgG) or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy. Obtained from the pooled plasma of several thousand healthy donors, IVIG is one of the most widely used immunotherapies for a large number of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.43,44 A recent open-label trial in three patients reported benefits of IVIG therapy (0.4 g/kg for 5 days) in severe SARS-CoV-2-induced pneumonia,45 thus providing another option for the management of COVID-19 patients. Another multicenter retrospective cohort study indicated that IVIG therapy could benefit critical COVID-19 patients, but dose (0.1–0.5 g/kg) and duration of therapy (5–10 days) were too variable.46 However, grouping of patients based on the dose of IVIG (>15 g/day or ≤15 g/day) and timing of infusion (>7 or ≤7 days since hospitalization) implied that beneficial effects are associated with high dose and early IVIG treatment.46 A retrospective study on 58 severe or critically ill cases of COVID-19 also found that adjunct therapy with IVIG within 48 h of hospitalization reduced hospital stay and ventilator use and improved 28-day mortality.47

Other than IL-6 and CRP, inflammatory parameters following IVIG immunotherapy were not evaluated in detail in these patients.46 Based on the vast literature on the mechanisms of IVIG, we suggest that IVIG suppresses the activation and secretion of inflammatory cytokines from the innate immune cells, blocks the inflammatory Th1 and Th17 responses, exerts scavenging effects on complement cascade, and possibly enhances T-reg cells.48,49 In addition, IVIG contains antibodies to diverse pathogens and their antigens,50,51 and hence, secondary infections could also be prevented in IVIG-treated patients.

Though these studies provide a pointer for initiating a randomized clinical trial with a large number of patients (NCT04261426; Table 1), certain key aspects need to be considered. First, the cost associated with IVIG immunotherapy could be considered prohibitive, and second, the necessity to reserve IVIG for patients whose survival essentially depends on this immunotherapy, particularly primary immunodeficient patients, must be weighed. Currently, there is a worldwide shortage of IVIG, and the COVID-19 pandemic will affect the collection of plasma from donors for IVIG production. Therefore, during this emergency period, providing IVIG to those patients who depend on it should take priority over initiating an IVIG trial in COVID-19 patients.

Passive Immunotherapy

Studies on COVID-19 patients’ sera confirmed the presence of seroconverted antibodies, such as IgG, IgM, and IgA, with varying kinetics and sensitivities.52,53 Findings in a monkey SARS-CoV-2 infection model confirmed that primary infection could protect the host from reinfection, perhaps aided by humoral immune responses.54 Therefore, passive immunization of SARS-CoV-2 by using convalescent plasma, intravenous hyperimmune globulin (containing high concentrations of neutralizing antibodies obtained from the pooled plasma of large number of recovered patients), or neutralizing monoclonal antibodies represent another potential therapeutic option.

A meta-analysis reported a significantly reduced mortality rate in SARS-CoV-infected patients following infusion of convalescent plasma. These patients recorded a rapid decline in their virus load.55 Although not conclusive, a report with MERS-CoV also suggested that the use of convalescent plasma could be an option for COVID-19.56 Similarly, a meta-analysis of patients with Spanish influenza pneumonia concluded that influenza-convalescent human blood products reduced the death risk.57 Hyperimmune globulin treatment in severe H1N1 influenza within 5 days of symptoms also reduced viral load and mortality in patients.58

Development of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies in cases of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV focused mainly on spike (S) protein as a target.59 Several monoclonal antibodies have demonstrated efficacy in experimental models.60,61 Either antibody libraries consisting of entire VH and VL genes of B cells or antigen-specific antibodies isolated from the memory B cells of convalescent COVID-19 patients could be used to obtain potent neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to SARS-CoV-2. Various laboratories are actively exploring this option.62 As S proteins of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 are phylogenetically closely related, SARS-CoV-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies with strong cross-neutralizing activity on SARS-CoV-2 represent an additional possibility.63,64

It is important to validate the neutralizing activity of aforementioned plasma or antibody preparations before using with COVID-19 patients, particularly in the case of convalescent plasma, as neutralizing activity might significantly differ in mildly versus severely ill patients. Because neutralizing monoclonal antibodies or hyperimmune globulins are pre-validated for their neutralizing activity, they do not pose such a dilemma. It is essential to note that the median seroconversion time for IgM and IgG was day 12 and day 14, respectively, following onset of COVID-19.65,66 At day 15 following onset of disease, the presence of antibodies was 94.3% in case of IgM and 79.8% for IgG.65 Therefore, convalescent plasma and hyperimmune globulins should be collected at least 3 weeks post-SARS-CoV-2 infection to increase the chances of obtaining high-titer neutralizing antibodies.

A preliminary report from China suggested that convalescent plasma therapy leads to improvement in 91 of 245 COVID-19 patients treated.67 An uncontrolled trial on transfusion of 400 mL of convalescent plasma (with viral neutralizing titers more than 1:40) in five patients critically ill with COVID-19 led to resolution of pulmonary lesions and reduction in the severity of the disease and viral loads.68 Similarly, treatment of ten severely ill COVID-19 patients with 200 mL of convalescent plasma containing viral-neutralizing antibody titers more than 1:640 (a dilution of plasma that neutralized 100 TCID50 [50% tissue-culture-infective dose] of SARS-CoV-2) led to reduced CRP levels, undetectable viremia, and improved clinical symptoms.69 Several randomized phase 2 and 3 clinical trials are already planned with convalescent plasma or hyperimmune globulin in many centers (Table 1), and the plasma fractionation industry has offered support for such efforts.70,71

Meplazumab, a humanized anti-CD147 IgG2 monoclonal antibody is under evaluation for COVID-19 pneumonia.72 This antibody therapy was aimed at preventing CD147-mediated SARS-CoV-2 viral entry and T cell chemotaxis. Preliminary data in a small number of patients indicated that meplazumab improved clinical course of the disease and normalized the peripheral lymphocyte count and CRP level.72

T-Reg-Cell-Targeted Therapies

T-reg cells are classically known to suppress anti-microbial protective immunity by affecting the activation of both innate and adaptive immune cells. However, T-reg cells are also important for preventing inflammation-associated tissue damage in acute infections.73,74 As mentioned earlier, the T-reg cell number is affected in COVID-19 patients, which explains in part severe inflammation and lung damage observed in seriously ill COVID-19 patients. T-reg cell therapy by adoptive transfer of ex vivo expanded autologous T-reg cells has been evaluated in autoimmune diseases. However, considering the cost and time required for the expansion of clinical-grade T-reg cells, adoptive T-reg cell therapy is not feasible for COVID-19. Alternatively, therapies that enhance T-reg cell number in vivo or use T-reg-cell-derived molecules would benefit severely ill COVID-19 patients.

IL-2-based Therapies to Expand T-Reg Cells

IL-2 complexed to a monoclonal antibody that recognizes the CD122/γc (dimeric IL-2 receptor) epitope of IL-2 was constructed in order to selectively activate T-reg cells that constitutively express trimeric IL-2R (dimeric IL-2 and CD25). This monoclonal antibody-IL-2 complex displayed promising results in experimental models of several autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.75 Recently, a human anti-IL-2 antibody named F5111.2 has been designed that potentiates T-reg cells by a structure-based mechanism wherein this antibody stabilizes IL-2 in a conformation that results in the preferential STAT5 phosphorylation of T-reg cells.76 Though not yet tested in humans, such approaches could boost T-reg cell number in COVID-19 patients and reduce inflammation. On the other hand, low-dose IL-2 therapy has been explored in the clinic for several autoimmune diseases to expand T-reg cells.77 But due to the fact that COVID-19 patients are reported to have high IL-2 in the blood, this option might not be useful. Our opinion is that neutralization of cytokines or immunomodulatory therapies are preferred over T-reg cell expansion strategies in view of the fact that, due to cytokine storm, T-reg cells might not be fully functional unless inflammatory cytokines are nullified.

T-Reg-Cell-Derived Therapeutic Molecules

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) plays a critical role in T-reg-cell-mediated suppression by interacting with CD80/86 on antigen-presenting cells and inducing trans-endocytosis of those co-stimulatory molecules. A recombinant CTLA-4 fusion protein consisting of the Fc portion of IgG1 (abatacept and belatacept) has been approved for the therapy of rheumatoid arthritis.78 This therapeutic molecule could also be tested for reducing inflammation in COVID-19 patients. The clinical spectra of SARS-CoV-2 infection in checkpoint inhibitor-treated cancer patients and abatacept/belatacept-treated autoimmune patients should provide a valuable indicator for the use of abatacept/belatacept.

Natural Killer (NK)-Cell-Based Immunotherapy

Currently, cellular therapies have not been given much consideration for COVID-19, possibly due to uncertainties of such approaches, time, and economic reasons. Nevertheless, because of their anti-viral effector functions, several NK-cell-based approaches are under consideration.

Little is known about the efficacy of NK cell therapy in infectious diseases. Conventional treatment in combination with NK cells (twice a week; 0.1–2 × 107 NK cells/kg body weight) is under clinical evaluation (NCT04280224; Table 1). However, the source of NK cells for the therapy is not precise in this trial. Recently, FDA has given permission to Celularity to investigate a universal NK cell therapy CYNK-001 in COVID-19 patients.79 CYNK-001 contains human placental CD34+ stem-cell-derived NK cells and are culture expanded.

An innovative NK-cell-based therapy with multipronged actions called NKG2D-ACE2 CAR-NK cell therapy is currently recruiting patients (NCT04324996; Table 1). NKG2D-ACE2 CAR-NK cells secrete IL-15 (to ensure long-term survival of NK cells) and GM-CSF-neutralizing scFv (to prevent CRS). In addition to clearance of virus-infected cells through ACE2, these NK cells can competitively inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection of susceptible cells, including alveolar epithelial cells. Although the strategy looks rational, toxicity due to clearance of virus-infected lung cells should be closely monitored.

In addition to NK cell therapy, other cell-based therapies, like SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell therapies, are also on the horizon.

Other Therapeutic Options for COVID-19

Many anti-viral drugs, such as protease inhibitors (camostat mesilate, lopinavir/ritonavir, and darunavir/cobicistat), nucleoside analogs (remdesivir and ribavirin), neuraminidase inhibitors (oseltamivir), RNA polymerase inhibitors (favipiravir), viral fusion inhibitor (umifenovir), and viral endonuclease inhibitor (baloxivir marboxil) are under evaluation as a treatment for SARS-CoV-2.8, 9, 10 An early compassionate use of remdesivir for 10 days in a small cohort of hospitalized COVID-19 patients reported clinical improvement in 36 of 53 treated patients (68%).10 Lopinavir/ritonavir and remdesivir were also found to be effective for MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV.8 Ribavirin, however, did not show benefits for MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV and was associated with severe side effects, like hemolytic anemia and liver dysfunction.27,32 The window of treatment is critical with anti-viral drugs, and they need to be used early in a disease. Late initiation of therapy with anti-viral drugs, particularly after 10–14 days post-appearance of clinical symptoms, might lead to a poor outcome.7

Though the study design and results were controversial, data from a small number of patients suggested utility of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 treatment.11 The follow-up study by the same group in a cohort of 1,061 COVID-19 patients demonstrated that a hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin combination when given during the early phase of the disease prevents aggravation of the disease and viral persistence.80 A randomized trial also observed improved pneumonia in hydroxychloroquine-treated patients.81 Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine possess a unique ability to increase the pH of lysosomes and hence prevent SARS-CoV-2 viral fusion and replication. In vitro studies on chloroquine suggested anti-SARS-CoV-2 effects of these molecules.82,83 Interestingly, previous studies have demonstrated anti-inflammatory activity of chloroquine for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. But other clinical trials did not support the use of hydroxychloroquine, particularly in hospitalized COVID-19 patients with hypoxic pneumonia or severe COVID-19 cases.84,85 Therefore, it appears that any efficacy hydroxychloroquine might have requires that it be given during the early phase of COVID-19 before progression to more severe disease. However, due to side effects, particularly cardiac, it is recommended to use chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine under strict medical surveillance. More evidence from randomized clinical trials is required.

Conclusions and Perspectives

The immediate surge in COVID-19-positive cases prompted clinicians all around the world to explore a range of therapeutic interventions for severely ill COVD-19 patients. Due to the lack of specific therapies and time required to develop potent vaccines for SARS-CoV-2, current investigations are focused on available anti-viral drugs.

As inflammation is the hallmark of SARS-CoV-2 infections, immunotherapies that target various players of inflammation are currently being investigated. We propose that a combination of anti-viral drugs and anti-inflammatory immunotherapies during early phase of the disease would function in a synergistic manner and provide maximum benefits. Anti-viral drugs would reduce the viral load and hence lessen the stimuli for inflammatory responses, and immunotherapies would correct the dysregulated inflammatory response and prevent lung damage. Care must be taken regarding an appropriate window of treatment and selecting the dose of anti-inflammatory immunotherapies, as excessive suppression of inflammation might reduce the capacity of the patient to mount anti-viral responses. Data from randomized trials are urgently needed to confirm the utility of the aforementioned immunotherapies in the management of critically ill COVID-19 patients.86,87

Acknowledgments

The majority of the articles referred to in this manuscript are unpublished and have not yet undergone the peer review process. They were obtained from the various preprint servers. We thank three anonymous reviewers for their suggestions. This work was supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), France; Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), France; Sorbonne Université, France; Université de Paris, France; and Institut Pasteur, France. J.B. also acknowledges the support of Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-19-CE17-0021(BASIN)), France and the COVID emergency fund from Université de Paris.

Author Contributions

Article Conception, J.B.; Literature Survey and Writing, S.R.B., L.G., and J.B.; Editing and Reviewing, S.V.K. and A.S.; Final Approval, all the authors.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guan W., Ni Z., Hu Y., Liang W., Ou C., He J., Liu L., Shan H., Lei C., Hui D.S.C., China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19 Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grasselli G., Zangrillo A., Zanella A., Antonelli M., Cabrini L., Castelli A., Cereda D., Coluccello A., Foti G., Fumagalli R., COVID-19 Lombardy ICU Network Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1574–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao X., Zhang B., Li P., Ma C., Gu J., Hou P., Guo Z., Wu H., Bai Y. Incidence, clinical characteristics and prognostic factor of patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.17.20037572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simonnet A., Chetboun M., Poissy J., Raverdy V., Noulette J., Duhamel A., Labreuche J., Mathieu D., Pattou F., Jourdain M., Lille Intensive Care COVID-19 and Obesity study group High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020 doi: 10.1002/oby.22831. Published online April 9, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao B., Wang Y., Wen D., Liu W., Wang J., Fan G., Ruan L., Song B., Cai Y., Wei M. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh A.K., Singh A., Shaikh A., Singh R., Misra A. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19 with or without diabetes: a systematic search and a narrative review with a special reference to India and other developing countries. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14:241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belhadi D., Peiffer-Smadja N., Lescure F.-X., Yazdanpanah Y., Mentré F., Laouénan C. A brief review of antiviral drugs evaluated in registered clinical trials for COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.18.20038190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grein J., Ohmagari N., Shin D., Diaz G., Asperges E., Castagna A., Feldt T., Green G., Green M.L., Lescure F.-X. Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007016. Published online April 10, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gautret P., Lagier J.C., Parola P., Hoang V.T., Meddeb L., Mailhe M., Doudier B., Courjon J., Giordanengo V., Vieira V.E. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949. Published online March 20, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Zhou Y., Fu B., Zheng X., Wang D., Zhao C., qi Y., Sun R., Tian Z., Xu X., Wei H. Pathogenic T cells and inflammatory monocytes incite inflammatory storm in severe COVID-19 patients. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwaa041. Published online March 13, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Z., Shi L., Wang Y., Zhang J., Huang L., Zhang C., Liu S., Zhao P., Liu H., Zhu L. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang W., He J., Lie P., Huang I., Wu S., Lin Y., Liu X. The definition and risks of cytokine release syndrome-like in 11 COVID-19-infected pneumonia critically ill patients: disease characteristics and retrospective analysis. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.26.20026989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin C., Zhou L., Hu Z., Zhang S., Yang S., Tao Y., Xie C., Ma K., Shang K., Wang W., Tian D.S. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diao B., Wang C., Tan Y., Chen X., Liu Y., Ning L., Chen L., Li M., Liu Y., Wang G. Reduction and functional exhaustion of T cells in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Front Immunol. 2020;11:827. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Y., Fu B., Zheng X., Wang D., Zhao C., qi Y., Sun R., Tian Z., Xu X., Wei H. Aberrant pathogenic GM-CSF+ T cells and inflammatory CD14+CD16+ monocytes in severe pulmonary syndrome patients of a new coronavirus. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.12.945576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liao M., Liu Y., Yuan J., Wen Y., Xu G., Zhao J., Chen L., Li J., Wang X., Wang F. Single-cell landscape of bronchoalveolar immune cells in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0901-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Z., Ren L., Zhang L., Zhong J., Xiao Y., Jia Z., Guo L., Yang J., Wang C., Jiang S. Heightened innate immune responses in the respiratory tract of COVID-19 patients. Cell Host Microbe. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.04.017. Published online April 28, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., Xia J., Zhou X., Xu S., Huang H., Zhang L., Zhou X., Du C. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. Published online March 13, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou B., She J., Wang Y., Ma X. Utility of ferritin, procalcitonin, and C-reactive protein in severe patients with 2019 novel coronavirus disease. Research Square. 2020 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-18079/v1. Published online March 19, 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo X., Zhou W., Yan X., Guo T., Wang B., Xia H., Ye L., Xiong J., Jiang Z., Liu Y. Prognostic value of C-reactive protein in patients with COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.21.20040360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu T., Zhang J., Yang Y., Ma H., Li Z., Zhang J., Cheng J., Zhang X., Zhao Y., Xia Z. The potential role of IL-6 in monitoring severe case of coronavirus disease 2019. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.01.20029769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., Xiang J., Wang Y., Song B., Gu X. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y., Jiang W., He Q., Wang C., Wang B., Zhou P., Dong N., Tong Q. Early, low-dose and short-term application of corticosteroid treatment in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia: single-center experience from Wuhan, China. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.06.20032342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu X., Chen T., Wang Y., Wang J., Zhang B., Li Y., Yan F. Adjuvant corticosteroid therapy for critically ill patients with COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.07.20056390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stockman L.J., Bellamy R., Garner P. SARS: systematic review of treatment effects. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arabi Y.M., Mandourah Y., Al-Hameed F., Sindi A.A., Almekhlafi G.A., Hussein M.A., Jose J., Pinto R., Al-Omari A., Kharaba A., Saudi Critical Care Trial Group Corticosteroid therapy for critically ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018;197:757–767. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1172OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.WHO . 2020. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when COVID-19 is suspected.https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov infection-is-suspected. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker K.H., Pearson J.C. 2020. Brigham and Women’s Hospital COVID-19 clinical guidelines.https://covidprotocols.org/protocols/04-therapeutics-and-clinical-trials [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé . 2019. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and serious infectious complications - Information Point.https://www.ansm.sante.fr/S-informer/Points-d-information-Points-d-information/Anti-inflammatoires-non-steroidiens-AINS-et-complications-infectieuses-graves-Point-d-Information [Google Scholar]

- 32.Momattin H., Mohammed K., Zumla A., Memish Z.A., Al-Tawfiq J.A. Therapeutic options for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)--possible lessons from a systematic review of SARS-CoV therapy. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2013;17:e792–e798. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Q., Zhou Y.-H., Yang Z.-Q. The cytokine storm of severe influenza and development of immunomodulatory therapy. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2016;13:3–10. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A., Gödel P., Subklewe M., Stemmler H.J., Schlößer H.A., Schlaak M., Kochanek M., Böll B., von Bergwelt-Baildon M.S. Cytokine release syndrome. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2018;6:56. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0343-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michot J.M., Albiges L., Chaput N., Saada V., Pommeret F., Griscelli F., Balleyguier C., Besse B., Marabelle A., Netzer F. Tocilizumab, an anti-IL6 receptor antibody, to treat Covid-19-related respiratory failure: a case report. Ann. Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.300. Published online April 2, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu X., Han M., Li T., Sun W., Wang D., Fu B., Zhou Y., Zheng X., Yang Y., Li X. Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with Tocilizumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005615117. Published online April 29, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yanik G.A., Ho V.T., Levine J.E., White E.S., Braun T., Antin J.H., Whitfield J., Custer J., Jones D., Ferrara J.L., Cooke K.R. The impact of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor etanercept on the treatment of idiopathic pneumonia syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2008;112:3073–3081. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yanik G.A., Grupp S.A., Pulsipher M.A., Levine J.E., Schultz K.R., Wall D.A., Langholz B., Dvorak C.C., Alangaden K., Goyal R.K. TNF-receptor inhibitor therapy for the treatment of children with idiopathic pneumonia syndrome. A joint Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Consortium and Children’s Oncology Group Study (ASCT0521) Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Altasciences Altasciences completes phase I study on gimsilumab for ARDS in COVID-19. 2020. https://www.altasciences.com/press-release/altasciences-completes-phase-i-study-gimsilumab-ards-covid-19

- 40.Roivant Sciences . 2020. Roivant announces development of anti-GM-CSF monoclonal antibody to prevent and treat acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in patients with COVID-19.https://roivant.com/roivant-announces-development-of-anti-gm-csf-monoclonal-antibody-to-prevent-and-treat-acute-respiratory-distress-syndrome-ards-in-patients-with-covid-19/ [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richardson P., Griffin I., Tucker C., Smith D., Oechsle O., Phelan A., Stebbing J. Baricitinib as potential treatment for 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease. Lancet. 2020;395:e30–e31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30304-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu D., Yang X.O. TH17 responses in cytokine storm of COVID-19: an emerging target of JAK2 inhibitor Fedratinib. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.005. Published online March 11, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bayry J., Negi V.S., Kaveri S.V. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in rheumatic diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2011;7:349–359. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perez E.E., Orange J.S., Bonilla F., Chinen J., Chinn I.K., Dorsey M., El-Gamal Y., Harville T.O., Hossny E., Mazer B. Update on the use of immunoglobulin in human disease: A review of evidence. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017;139(3S):S1–S46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cao W., Liu X., Bai T., Fan H., Hong K., Song H., Han Y., Lin L., Ruan L., Li T. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin as a therapeutic option for deteriorating patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020;7:ofaa102. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shao Z., Sr., Feng Y., Zhong L., Xie Q., Lei M., Liu Z., Wang C., Ji J., Liu H., Gu Z. Clinical efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in critical patients with COVID-19: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.11.20061739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xie Y., Cao S., Li Q., Chen E., Dong H., Zhang W., Yang L., Fu S., Wang R. Effect of regular intravenous immunoglobulin therapy on prognosis of severe pneumonia in patients with COVID-19. J. Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.044. Published online April 10, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwab I., Nimmerjahn F. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy: how does IgG modulate the immune system? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13:176–189. doi: 10.1038/nri3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Galeotti C., Kaveri S.V., Bayry J. IVIG-mediated effector functions in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Int. Immunol. 2017;29:491–498. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxx039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bayry J., Lacroix-Desmazes S., Kazatchkine M.D., Kaveri S.V. Intravenous immunoglobulin for infectious diseases: back to the pre-antibiotic and passive prophylaxis era? Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2004;25:306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shopsin B., Kaveri S.V., Bayry J. Tackling difficult Staphylococcus aureus infections: antibodies show the way. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:555–557. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Long Q., Liu B.-Z., Deng H.-J., Wu G.-C., Deng K., Chen Y.K., Liao P., Qiu J.-F., Lin Y., Cai X.-F. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okba N.M.A., Müller M.A., Li W., Wang C., GeurtsvanKessel C.H., Corman V.M., Lamers M.M., Sikkema R.S., de Bruin E., Chandler F.D. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2-specific antibody responses in coronavirus disease 2019 patients. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.18.20038059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bao L., Deng W., Gao H., Xiao C., Liu J., Xue J., Lv Q., Liu J., Yu P., Xu Y. Reinfection could not occur in SARS-CoV-2 infected rhesus macaques. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.13.990226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mair-Jenkins J., Saavedra-Campos M., Baillie J.K., Cleary P., Khaw F.-M., Lim W.S., Makki S., Rooney K.D., Nguyen-Van-Tam J.S., Beck C.R., Convalescent Plasma Study Group The effectiveness of convalescent plasma and hyperimmune immunoglobulin for the treatment of severe acute respiratory infections of viral etiology: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. J. Infect. Dis. 2015;211:80–90. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ko J.-H., Seok H., Cho S.Y., Ha Y.E., Baek J.Y., Kim S.H., Kim Y.-J., Park J.K., Chung C.R., Kang E.-S. Challenges of convalescent plasma infusion therapy in Middle East respiratory coronavirus infection: a single centre experience. Antivir. Ther. (Lond.) 2018;23:617–622. doi: 10.3851/IMP3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luke T.C., Kilbane E.M., Jackson J.L., Hoffman S.L. Meta-analysis: convalescent blood products for Spanish influenza pneumonia: a future H5N1 treatment? Ann. Intern. Med. 2006;145:599–609. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-8-200610170-00139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hung I.F.N., To K.K.W., Lee C.-K., Lee K.-L., Yan W.-W., Chan K., Chan W.-M., Ngai C.-W., Law K.-I., Chow F.-L. Hyperimmune IV immunoglobulin treatment: a multicenter double-blind randomized controlled trial for patients with severe 2009 influenza A(H1N1) infection. Chest. 2013;144:464–473. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiang S., Hillyer C., Du L. Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and other human coronaviruses. Trends Immunol. 2020;41:355–359. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sui J., Li W., Murakami A., Tamin A., Matthews L.J., Wong S.K., Moore M.J., Tallarico A.S.C., Olurinde M., Choe H. Potent neutralization of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus by a human mAb to S1 protein that blocks receptor association. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:2536–2541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307140101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.ter Meulen J., van den Brink E.N., Poon L.L., Marissen W.E., Leung C.S., Cox F., Cheung C.Y., Bakker A.Q., Bogaards J.A., van Deventer E. Human monoclonal antibody combination against SARS coronavirus: synergy and coverage of escape mutants. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen X., Li R., Pan Z., Qian C., Yang Y., You R., Zhao J., Liu P., Gao L., Li Z. Human monoclonal antibodies block the binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0426-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yuan M., Wu N.C., Zhu X., Lee C.D., So R.T.Y., Lv H., Mok C.K.P., Wilson I.A. A highly conserved cryptic epitope in the receptor-binding domains of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Science. 2020;368:630–633. doi: 10.1126/science.abb7269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang C., Li W., Drabek D., Okba N.M.A., van Haperen R., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., van Kuppeveld F.J.M., Haagmans B.L., Grosveld F., Bosch B.-J. A human monoclonal antibody blocking SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun. 2020;11:2251. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16256-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao J., Yuan Q., Wang H., Liu W., Liao X., Su Y., Wang X., Yuan J., Li T., Li J. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344. Published online March 28, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guo L., Ren L., Yang S., Xiao M., Chang D., Yang F., Dela Cruz C.S., Wang Y., Wu C., Xiao Y. Profiling early humoral response to diagnose novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa310. Published online March 21, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xinhua . 2020. China puts 245 COVID-19 patients on convalescent plasma therapy.http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-02/28/c_138828177.htm [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shen C., Wang Z., Zhao F., Yang Y., Li J., Yuan J., Wang F., Li D., Yang M., Xing L. Treatment of 5 critically ill patients with COVID-19 with convalescent plasma. JAMA. 2020;323:1582–1589. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Duan K., Liu B., Li C., Zhang H., Yu T., Qu J., Zhou M., Chen L., Meng S., Hu Y. Effectiveness of convalescent plasma therapy in severe COVID-19 patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:9490–9496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004168117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Takeda . 2020. Takeda initiates development of a plasma-derived therapy for COVID-19.https://www.takeda.com/newsroom/newsreleases/2020/takeda-initiates-development-of-a-plasma-derived-therapy-for-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grifols . 2020. Grifols announces formal collaboration with US government to produce the first treatment specifically targeting COVID-19.www.grifols.com/en/view-news/-/news/grifols-announces-formal-collaboration-with-us-government-to-produce-the-first-treatment-specifically-targeting-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bian H., Zheng Z.-H., Wei D., Zhang Z., Kang W.-Z., Hao C.-Q., Dong K., Kang W., Xia J.-L., Miao J.-L. Meplazumab treats COVID-19 pneumonia: an open-labelled, concurrent controlled add-on clinical trial. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.21.20040691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wing J.B., Tanaka A., Sakaguchi S. Human FOXP3+ regulatory T cell heterogeneity and function in autoimmunity and cancer. Immunity. 2019;50:302–316. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stephen-Victor E., Bosschem I., Haesebrouck F., Bayry J. The yin and yang of regulatory T cells in infectious diseases and avenues to target them. Cell. Microbiol. 2017;19:e12746. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Webster K.E., Walters S., Kohler R.E., Mrkvan T., Boyman O., Surh C.D., Grey S.T., Sprent J. In vivo expansion of T reg cells with IL-2-mAb complexes: induction of resistance to EAE and long-term acceptance of islet allografts without immunosuppression. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:751–760. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Trotta E., Bessette P.H., Silveria S.L., Ely L.K., Jude K.M., Le D.T., Holst C.R., Coyle A., Potempa M., Lanier L.L. A human anti-IL-2 antibody that potentiates regulatory T cells by a structure-based mechanism. Nat. Med. 2018;24:1005–1014. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0070-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abbas A.K., Trotta E., R Simeonov D., Marson A., Bluestone J.A. Revisiting IL-2: biology and therapeutic prospects. Sci. Immunol. 2018;3:eaat1482. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aat1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rosenblum M.D., Gratz I.K., Paw J.S., Abbas A.K. Treating human autoimmunity: current practice and future prospects. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4:125sr1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Slater H. FDA accepts IND for NK cell therapy CYNK-001 to treat patients with COVID-19. CancerNetwork. 2020 https://www.cancernetwork.com/immuno-oncology/fda-accepts-ind-nk-cell-therapy-cynk-001-treat-patients-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Million M., Lagier J.-C., Gautret P., Colson P., Fournier P.-E., Amrane S., Hocquart M., Mailhe M., Esteves-Vieira V., Doudier B. Early treatment of COVID-19 patients with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin: A retrospective analysis of 1061 cases in Marseille, France. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen Z., Hu J., Zhang Z., Jiang S., Han S., Yan D., Zhuang R., Hu B., Zhang Z. Efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID-19: results of a randomized clinical trial. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.22.20040758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L., Yang X., Liu J., Xu M., Shi Z., Hu Z., Zhong W., Xiao G. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu J., Cao R., Xu M., Wang X., Zhang H., Hu H., Li Y., Hu Z., Zhong W., Wang M. Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Cell Discov. 2020;6:16. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0156-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mahevas M., Tran V.-T., Roumier M., Chabrol A., Paule R., Guillaud C., Gallien S., Lepeule R., Szwebel T.-A., Lescure X. No evidence of clinical efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients hospitalized for COVID-19 infection with oxygen requirement: results of a study using routinely collected data to emulate a target trial. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.10.20060699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Molina J.M., Delaugerre C., Le Goff J., Mela-Lima B., Ponscarme D., Goldwirt L., de Castro N. No evidence of rapid antiviral clearance or clinical benefit with the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in patients with severe COVID-19 infection. Med. Mal. Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2020.03.006. Published online March 30, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Geleris J., Sun Y., Platt J., Zucker J., Baldwin M., Hripcsak G., Labella A., Manson D., Kubin C., Barr R.G. Observational study of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bonam S.R., Muller S., Bayry J., Klionsky D.J. Autophagy as an emerging target for COVID-19: lessons from an old friend, chloroquine. Autophagy. 2020 doi: 10.1080/15548627.2020.1779467. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]