Abstract

Pressure ulcers (PUs) frequently occur in individuals with limited mobility including patients that are hospitalized or obese. PUs are challenging to resolve when infected by antibiotic-resistant bacteria, particularly methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). In this study, we investigated the potential of repurposing auranofin to treat pressure ulcers infected with MRSA. Auranofin’s in vitro activity against strains of S. aureus (including MRSA) was not affected in the presence of higher bacterial inoculum (107 CFU/mL) or by lowering the pH in standard media to simulate the environment present on the surface of the skin. Additionally, S. aureus did not develop resistance to auranofin after repeated exposure for two weeks via a multi-step resistance selection experiment. In contrast, S. aureus resistance to mupirocin emerged rapidly. Moreover, auranofin exhibited a long postantibiotic effect (PAE) in vitro against three strains of S. aureus tested. Remarkably, topical auranofin completely eradicated MRSA (8-log10 reduction) in infected PUs of obese mice after just four days of treatment. This was superior to both topical mupirocin (1.96-log10 reduction) and oral clindamycin (1.24-log10 reduction), which are used to treat infected PUs clinically. The present study highlights auranofin’s potential to be investigated further as a treatment for mild-to-moderate PUs infected with S. aureus.

Subject terms: Drug discovery, Skin models, Bacteria

Introduction

Pressure ulcers (PUs), also commonly referred to as pressure sores or decubitus ulcers, are defined as “localized injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue” that often form when skin is compressed between bone and an external surface1. In the United States (U.S.) alone, nearly 1.6 million pressure ulcers develop in hospitalized patients each year2. Additionally, PUs are the second leading source of hospital readmissions each year, impacting between 1.3 and 3 million people3.

Bacterial infection of PUs is common and problematic as infection can (1) impair healing of the ulcerated tissue, (2) lead to more serious disseminated infections including osteomyelitis and sepsis, and (3) result in increased treatment costs4–6. Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-negative bacilli are the most frequent bacterial pathogens linked to infected PUs4,7. Such infections can be treated with systemic (such as clindamycin) or topical antibiotics (such as mupirocin or fusidic acid)7,8. However, the formation of biofilms within PUs that protect the pathogen from the effect of many antibiotics, secretion of toxins by the pathogen that lead to further damage of the skin and surrounding tissues, and the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains, including methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA), have compounded treatment of infected PUs4. Thus, identifying new antibacterial agents effective in treating PUs infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria are needed.

Auranofin is a gold-containing drug that received FDA approval in 1985 as a second-line therapeutic to treat rheumatoid arthritis. Recently, there has been renewed interest in repurposing auranofin to treat an array of medical diseases including cancer, parasitic infections, and bacterial skin and soft tissue infections9–14. As infected PUs are a notable challenge to obese individuals, the main objective of the present study was to investigate auranofin’s ability to reduce the burden of MRSA in infected PUs in obese mice.

Results

Antibacterial activity of auranofin against staphylococcal isolates under acidic pH and high inoculum conditions

Previous reports have investigated the in vitro antibacterial activity of auranofin in standard media (such as cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth or Tryptic soy broth at neutral pH) with a fixed bacterial inoculum size (~105 CFU/mL), following guidelines provided by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Under these standard conditions, we determined that auranofin exhibited potent in vitro antibacterial activity against strains of methicillin-sensitive S. aureus, MRSA, and VRSA with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values ranging from 0.015 –0.06 µg/mL (Table 1). These results are in agreement with previous reports13–15. The activity of auranofin was similar to clindamycin (MIC ranged from 0.015–0.03 µg/mL), although clindamycin was ineffective against the two VRSA strains tested (MIC > 8 µg/mL). Auranofin exhibited more potent in vitro activity against all six clinical staphylococcal isolates tested relative to mupirocin (MIC ranged from 0.06–0.25 µg/mL, except for clinical isolate S. aureus NRS107 which exhibits high-level resistance to mupirocin).

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC, in µg/mL) of auranofin and control antibiotics (clindamycin and mupirocin) tested against strains of Staphylococcus aureus in the presence of different inoculum size and acidic pH.

| Bacterial Strain | Genotype | Auranofin | Clindamycin | Mupirocin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inoculum size (CFU/mL) | pH 6.0 | Inoculum size (CFU/mL) | pH 6.0 | Inoculum size (CFU/mL) | pH 6.0 | ||||||||

| 105 | 106 | 107 | 105 | 106 | 107 | 105 | 106 | 107 | |||||

| ATCC 6538a | mecA− | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.0039 |

| NRS107a | mecA− | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.03 | 0.0039 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.03 | 0.125 | >8 | >8 | >8 | >8 |

| NRS384 (USA300)b | mecA+ (subtype IV); pvl+ | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.015 |

| NRS123 (USA400)b | mecA+ (subtype IV); pvl+; seb+ | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.015 |

| VRS9c | mecA+; vanA+ | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | >8 | >8 | >8 | >8 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.0078 |

| VRS12c | — | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | >8 | >8 | >8 | >8 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.0078 |

aMethicillin-sensitive S. aureus.

bMethicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).

cVancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA).

We next evaluated the impact of bacterial inoculum size on the antibacterial activity of auranofin. Auranofin’s antibacterial activity was identical to or two-fold higher as the inoculum size increased from 105 CFU/mL to 106 CFU/mL to 107 CFU/mL (Table 1), suggesting the drug’s activity was not impacted by inoculum size. This was similar to the result observed with mupirocin, in agreement with a previous study16. In contrast, clindamycin’s activity was negatively affected as the bacterial inoculum size increased (MIC increased two- to eight-fold against S. aureus ATCC 6538, S. aureus NRS107, MRSA NRS123, and MRSA NRS384).

In addition to examining the impact of bacterial inoculum size on the antibacterial activity of auranofin, we also investigated the impact of changing the pH of the media. Auranofin’s antibacterial activity was similar to or slightly more potent in media that was acidic (pH 6.0), MIC was two- to four-fold lower against S. aureus NRS107 and VRS9, compared to media at neutral pH (Table 1), suggesting that the drug’s activity should remain stable or be slightly enhanced in acidic environments, such as the surface of the skin. Both clindamycin’s and mupirocin’s antibacterial activity were affected by pH. Under acidic pH conditions, clindamycin’s MIC was negatively impacted and increased eight- to 16-fold relative to the antibiotic’s activity at neutral pH. In contrast, mupirocin’s antibacterial activity was enhanced by 16- to 32-fold (MIC ranged from 0.0039–0.015 µg/mL). The enhanced activity of mupirocin under acidic conditions is known and is advantageous for topical treatment of S. aureus skin and wound infections16,17.

Evaluation of S. aureus resistance formation to auranofin after multiple exposures

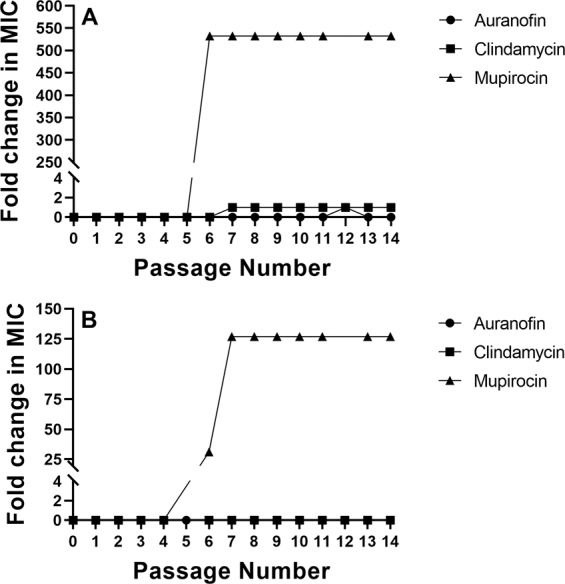

We moved to evaluate the ability of S. aureus to develop resistance to auranofin after multiple exposures to the drug, similar to how the drug would be administered clinically to resolve a bacterial infection. A multi-step resistance selection experiment with auranofin was conducted with two strains of S. aureus (S. aureus ATCC 6538 and MRSA NRS384) to investigate this issue further. No shift in the MIC values for auranofin against either S. aureus strain was observed during the duration of the study (Fig. 1). Similar to auranofin, neither strain of S. aureus developed resistance to clindamycin over the 14-day period. Only a one-fold increase in the MIC of clindamycin was observed after the seventh passage against S. aureus ATCC 6538. In contrast, S. aureus ATCC 6538 developed resistance to mupirocin after the fifth passage (MIC increased >500-fold) while MRSA NRS384 developed resistance to mupirocin after the fourth passage (MIC increased >30-fold). This was similar to previous studies that found clinical isolates of S. aureus developed resistance to mupirocin rapidly after 2 to 14 days of exposure via a multi-step resistance selection study18,19.

Figure 1.

Multi-step resistance selection for auranofin, clindamycin, and mupirocin evaluated against S. aureus. Drugs were serially passaged daily against (A) S. aureus ATCC 6538 and (B) methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) NRS384 (USA300) for 14 days. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of each test agent was determined after each passage. Data are presented as fold-change in MIC relative to the previous passage.

Postantibiotic effect of auranofin and control antibiotics against S. aureus isolates

Auranofin exhibited a long PAE of seven hours against two MRSA strains (NRS123 and NRS384) (Table 2). Against S. aureus ATCC 6538, the PAE of auranofin exceeded nine hours. Clindamycin exhibited a PAE that ranged from four hours (against MRSA NRS123) to six hours (against S. aureus ATCC 6538). The variation in PAE for clindamycin is in agreement with Xue et al.’s report, that found the PAE of clindamycin against 21 strains of S. aureus ranged from 0.4 to 3.9 hours and was dependent on length of exposure and concentration of drug used20. Mupirocin exhibited a shorter PAE of four hours, under the same conditions, against all three strains of S. aureus. This was similar to a previous study by Rittenhouse et al., that found mupirocin (at 4 × MIC) exhibited a short PAE that ranged between 2.2 and 2.9 hours21.

Table 2.

Postantibiotic effect of auranofin and control antibiotics (clindamycin and mupirocin) tested (at 5 × MIC) against strains of Staphylococcus aureus.

| Bacterial Strain | Postantibiotic Effect (hours) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Auranofin | Clindamycin | Mupirocin | |

| S. aureus ATCC 6538 | >9 | 6 | 4 |

| MRSA NRS384 (USA300) | 7 | 5 | 4 |

| MRSA NRS123 (USA400) | 7 | 4 | 4 |

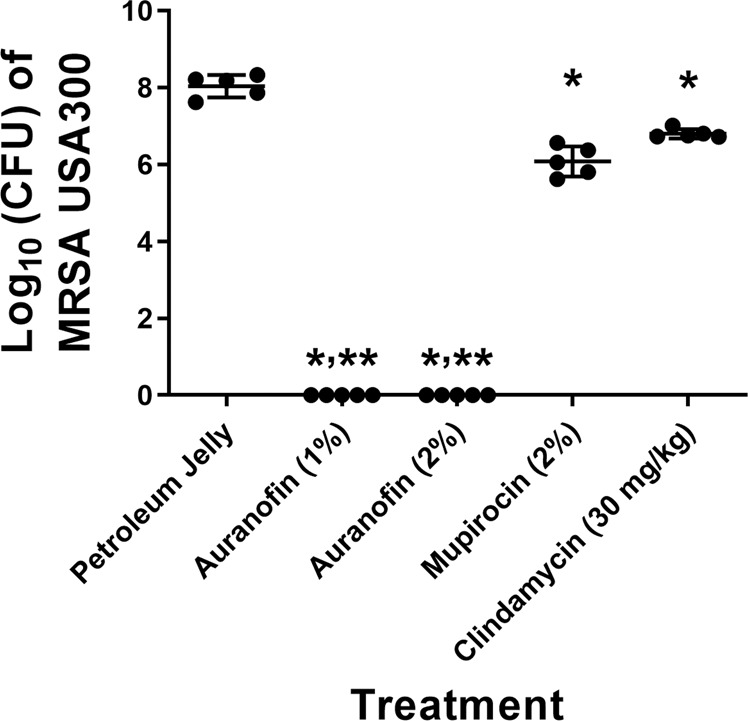

Auranofin eradicates MRSA in infected pressure ulcers in vivo in obese mice

Auranofin was superior (P < 0.0001) to both topical mupirocin and oral clindamycin in reducing the burden of MRSA in infected PUs of obese TALLYHO/JngJ mice. After just four days of treatment, auranofin (2% topical suspension) completely eradicated MRSA from the infected PUs in all five mice (Fig. 2). This was equivalent to reducing the bacterial burden by 8-log10 relative to mice receiving the negative control (vehicle alone). Reducing the concentration of auranofin to a 1% topical preparation yielded the same result as no viable MRSA colonies were present in infected PUs of all five mice. Topical mupirocin reduced the burden of MRSA by 1.96-log10 (P < 0.0001) in infected PUs. Oral clindamycin, though effective in producing a statistically significant reduction in bacterial burden, was the least potent antibacterial as clindamycin reduced the burden of MRSA in infected PUs by only 1.24-log10 (P < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Burden of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) USA300 in the wounds of obese mice after treatment with auranofin and control antibiotics. The dorsum of female TALLYHO/JngJ were exposed to 10 cycles (two hours on, one hour off) of rare earth magnets to induce the formation of pressure ulcers. Ulcers were infected with MRSA USA300 and 48 hours post-infection were treated topically either with auranofin (1% or 2%) or mupirocin (2%) twice daily for four days (n = 5 mice/group). One group of mice received oral clindamycin (30 mg/kg) once daily and another group received the vehicle alone (petroleum jelly administered topically) twice daily for four days. Mice were humanely euthanized 12 hours after the final treatment dose and wounds were harvested aseptically to determine reduction in bacterial burden post-treatment. Data are presented as log10 (total MRSA CFU per wound) for each mouse and were evaluated using a one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnet’s test for multiple comparisons. One asterisk (*) indicates statistical difference for test agents relative to petroleum jelly (negative control, P < 0.05). Two asterisks (**) indicates statistical different between auranofin and mupirocin-treated mice (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Pressure ulcers significantly impact individuals that are immobilized or exhibit limited mobility, including patients in hospitals and individuals that are obese. Obesity is often linked to other co-morbidities, including hypertension and Type 2 diabetes, which can result in hospitalizations. Indeed, 25% of patients that present in hospital intensive care units (ICU) are obese22. The rate of obesity has tripled in the past 40 years and impacts nearly 13% of the adult population (>650 million people as of 2016) worldwide and nearly 40% of the adult population in the U.S. (>93 million individuals)23,24. Due to limited mobility, obese individuals, both in the ICU and in the community setting, tend to be at a higher risk of developing pressure ulcers22. Bacterial infections of pressure ulcers further complicate treatment and healing of PUs. Increased bacterial burden in PUs impedes the formation of granulation tissue which can delay wound healing6. It has been postulated that healing of PUs is hindered when the bacterial population exceeds 105 CFU/g, though more recent studies have found that bacterial populations below the 105 CFU/g threshold may be deleterious to healing of infected PUs6,25. Thus, finding antibacterial agents capable of rapidly eliminating bacteria in infected PUs would potentially aid in enhancing resolution of infected PUs. Antibiotics currently used to treat PUs infected with bacteria, such as S. aureus, may be ineffective due to multiple factors including bacterial resistance to the antibiotic, the presence of biofilms, and inability to neutralize toxins secreted by bacteria that further damage the infected lesions. Identifying novel therapeutics capable of treating infected PUs are needed.

As noted in the introduction, auranofin was originally approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Though auranofin had the advantage of being an orally-administered gold drug and was associated with fewer adverse reactions in patients, injectable gold compounds were found to be more effective in resolving symptoms associated with rheumatoid arthritis26,27. This reason combined with the emergence of more potent antirheumatic agents, such as oral methotrexate, resulted in decreased clinical use of auranofin by the early 1990s28. However, recent studies have investigated repurposing auranofin as an antibacterial agent. Auranofin has potent activity against important Gram-positive bacterial pathogens including MRSA and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) and exerts its antibacterial effect by inhibiting multiple biosynthetic pathways, including protein synthesis13. Previously, we demonstrated that auranofin applied topically is effective in significantly reducing the burden of MRSA in an uncomplicated abscess model in mice and in decreasing expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, MCP-1, IL-1β, and IL-6) that may impair wound healing14. Furthermore, auranofin inhibited the production of key toxins (Panton-Valentine leucocidin and α-hemolysin) produced by MRSA that damage host tissues and was effective in eradicating S. aureus biofilm in vitro13,14. These features, we hypothesized, would be beneficial in treating mild-to-moderate pressure ulcers infected with MRSA.

Initially, we investigated the effect of increasing the bacterial inoculum size and the effect of pH on the antibacterial activity of auranofin. Though an inoculum size ~105 CFU/mL is used in standard antibacterial susceptibility assays, a higher inoculum (>106 CFU/mL) is often used to infect animals in in vivo infection models. Additionally, infected PUs clinically present with a bacterial burden that exceeds 105 CFU/g6. We thus evaluated the impact of increasing the bacterial inoculum (above standard broth microdilution assay conditions) on the antibacterial activity of auranofin. Auranofin’s in vitro antibacterial activity increased two-fold against three of the six S. aureus strains tested as the bacterial inoculum size increased from 105 to 107 CFU/mL. Next, we assessed the effect of pH on auranofin’s antibacterial activity. The skin surface represents an acidic environment (pH ranging from 4.0 to 6.0) which differs from the neutral pH used in standard media29. Thus, to determine if the acidic environment on the surface of the skin may affect auranofin’s antibacterial activity, particularly if used topically, the MIC of auranofin in acidic conditions (media adjusted to pH 6.0) was determined. Auranofin’s antibacterial activity was unaffected or slightly more potent under acidic conditions (pH 6.0), compared to media at neutral pH. This indicates that auranofin’s activity may be slightly enhanced in acidic environments, such as the surface of the skin.

After evaluating the effect of bacterial inoculum size and pH on the antibacterial activity of auranofin, we next evaluated the ability of S. aureus to develop resistance to auranofin. Bacteria have a proclivity to acquire or develop resistance to antibiotics, particularly after repeated exposure. Previously, our research group determined that S. aureus was unable to develop spontaneous resistance to auranofin (at 3 ×, 5 ×, and 10 × MIC) via a single-step resistance selection experiment13. Harbut et al., also noted the inability to isolate Mycobacterium tuberculosis spontaneous mutants exhibiting resistance to auranofin11. Using a multi-step resistance selection assay, both S. aureus ATCC 6538 and MRSA NRS384 did not develop resistance to auranofin (no shift in the MIC) after 14 passages. This was similar to a recent report investigating auranofin’s activity against vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium30, which indicates bacteria are unlikely to develop resistance rapidly to auranofin.

After determining that the antibacterial activity of auranofin was not impacted by a lower pH or higher bacterial inoculum and confirming the low potential of S. aureus to develop resistance to auranofin after multiple passages, we moved to investigate if auranofin exhibits a postantibiotic effect (PAE). In the 1940s, Parker et al., noted that penicillin could suppress growth of staphylococci, even after a very short exposure to the antibiotic31. This phenomenon was later termed as postantibiotic effect and has been proposed to impact dosing regimens for antibiotics. Antibiotics that exhibit a long PAE are thought to be beneficial, as it is postulated that these agents may require fewer doses clinically20. Auranofin (at 5 × MIC) exhibited a long PAE that ranged from seven hours against two MRSA strains to over nine hours against S. aureus ATCC 6538. These results suggest auranofin is capable of suppressing S. aureus growth for a long period of time, even after a short exposure to the drug. This would potentially reduce the frequency that auranofin would need to be administered clinically to treat an infection caused by S. aureus.

The final step in our study was to evaluate auranofin’s ability to reduce the burden of S. aureus in infected PUs in an animal model. In order to evaluate the effectiveness of auranofin in treating infected PUs, we developed a model using female TALLYHO/JngJ mice. Female TALLYHO/JngJ mice represent a new animal model to investigate different disease indications in obese mice that are nondiabetic32. This particular strain of mice exhibits characteristic features of obesity including increased weight gain, moderate hyperleptinemia, moderate hyperinsulinemia, as well as impaired wound healing33,34. Utilizing two neodymium rare Earth magnets applied via a series of ischemia-reperfusion cycles, moderate ulcers that exhibited full-thickness skin loss with limited exudate were formed. The magnets possessed a strength of 3,466 G which exceeds 50 mm Hg compression pressure. This is important as a previous study found a compression pressure that exceeds 50 mm Hg will decrease capillary blood flow by 80% resulting in decreased oxygen delivery to cells, ultimately resulting in cell death35. The pressure ulcers were subsequently infected with MRSA NRS384 before treatment was initiated. Topical auranofin (both at 1% and 2%) rapidly eradicated the burden of MRSA in the infected wounds after only four days of treatment. This was superior to both topical mupirocin (2%) and oral clindamycin (30 mg/kg).

Though clindamycin is used clinically to treat skin infections and wounds caused by S. aureus, several issues have been noted. First, clindamycin usage has been linked to gastrointestinal toxicity and diarrhea36. Second, clindamycin’s antibacterial activity against Gram-positive bacteria and anaerobic Gram-negative rods can lead to dysbiosis of the natural microflora present in the gastrointestinal tract and increase susceptibility to infections by opportunistic pathogens, such as Clostridioides difficile36. Identifying alternative options to the use of systemic antibacterial agents, including the use of topical antibacterials capable of rapidly eliminating bacteria in infected PUs such as auranofin, would be beneficial. However, it should be noted that the most recent guidelines from the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP), National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP) and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (PPPIA) on the treatment of infected pressure ulcers only recommends the use of systemic antibiotics37. However, topical antiseptics, including those active against biofilms, are recommended to use to control bacterial burden in infected PUs that exhibit delayed wound healing. Though use of topical antibiotics is not included in the current treatment guidelines for infected PUs, the use of a topical antibiotic to treat wounds infected with bacteria has been proposed to have multiple benefits including delivering a high concentration of drug directly to the site of infection, decreasing the likelihood of systemic toxicity to the host, and easier/better patient compliance38.

The positive result observed with auranofin in our infected PU mice model was more pronounced compared to previous studies that have investigated auranofin as a topical antibacterial agent to treat MRSA skin wound infections14,39. For example, Thangamani et al., found that auranofin applied topically to uncomplicated skin abscesses in mice resulted in a 2.51-log10 reduction (for 1% auranofin) to 3.64-log10 reduction (for 2% auranofin) in MRSA burden14. We suspect the differences observed between these mice studies are due to multiple factors including 1.) different species of mice used (for example healthy BALB/c or CD-1 mice compared to TALLYHO/JngJ obese mice in our study), 2.) how skin wounds were formed (intradermal injection of bacteria to induce formation of simple abscesses compared to magnets to induce pressure ulcer formation in our study), and 3.) the use of a wound dressing (Tegaderm) in our study to hinder mice from grooming/removing drug from the infection site which permitted enhanced contact time for the drug to exert its effect. Wound dressings such as Tegaderm have an additional benefit in that they are permeable to water vapor and oxygen, which helps keep wounds moist, and prevents contamination of wounds by other microorganisms40. Previous studies have found that wounds that are kept moist heal more rapidly as an optimal environment is present for cells involved in wound healing41–44. Thus, the incorporation of a wound dressing into our PU mouse model, we suspect, played a role in the enhanced efficacy of auranofin observed relative to other published reports.

In conclusion, pressure ulcers are a common occurrence in individuals with limited mobility including patients that are hospitalized or obese. In this study, we investigated the effectiveness of auranofin, as a new antibacterial agent, to treat pressure ulcers infected with MRSA. Auranofin’s antibacterial activity in vitro was stable even in the presence of acidic pH or high bacterial inoculum size compared to both clindamycin and mupirocin. In obese mice, topical auranofin was superior to both topical mupirocin and oral clindamycin in rapidly eliminating the burden of MRSA in infected PUs. The complete eradication of MRSA from the PUs is postulated to be beneficial to aid in wound repair and healing though further studies will be needed to investigate this point in more depth.

Methods

Antibiotics and reagents

Staphylococcal clinical isolates were acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) or the Biodefense and Emerging Infections Research Resources Repository (BEI Resources, Manassas, VA, USA). Auranofin (Chem-Impex International, Wood Dale, IL, USA), clindamycin hydrochloride monohydrate (Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Tokyo, Japan), and mupirocin (PanReac AppliChem ITW Reagents, Darmstadt, Germany) were purchased from commercial vendors and dissolved either in sterile water or in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to prepare stock 10 mg/mL solutions. Cation-adjusted Mueller Hinton broth (CA-MHB, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD, USA), Tryptic soy agar (TSA, Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, CA, USA), Tryptic soy broth (TSB, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD, USA), mannitol salt agar (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, CA, USA), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Corning, Manassas, VA, USA), hydrochloric acid (HCl, Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA), petroleum jelly, rare earth magnets (Magcraft, Vienna, VA, USA), betadine solution (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA), Tegaderm (3 M, St. Paul, MN, USA), Uro-bond V (Urocare, Pomona, CA, USA), and 96-well plates were all purchased from commercial vendors. Buprenorphine was provided by the Purdue Translational Pharmacology Core at Purdue University.

Evaluation of the effect of bacterial inoculum size and pH on auranofin and control antibiotics’ antibacterial activity

The broth microdilution assay was used to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of auranofin, clindamycin, and mupirocin against six different clinical isolates of S. aureus45. A preparation of S. aureus to a McFarland 0.5, in sterile PBS, was subsequently diluted 1:3 (to reach 107 CFU/mL), 1:30 (to reach 106 CFU/mL), or 1:300 (to reach 105 CFU/mL) in sterile CA-MHB (pH 7.4). An aliquot of each inoculum preparation was serially-diluted and plated onto TSA to confirm the initial inoculum size. To investigate the effect of pH on antibacterial activity, an aliquot of 1 M HCl was added to CA-MHB until a pH of 6.0 ± 0.1 was reached. Test agents were added in triplicate wells to a 96-well plate and serially diluted two-fold with the bacterial inoculum. Plates were incubated at 37°C for at least 18 hours before the MIC was recorded by visual inspection of growth.

Multi-step resistance selection experiment

To determine if S. aureus would develop resistance to auranofin after repeated exposure, a multi-step resistance experiment was conducted, as described in previous reports46,47. The broth microdilution assay was used to determine the initial MIC for auranofin, clindamycin, and mupirocin, in triplicate, as described above. For each subsequent passage, an aliquot (5 µL) of bacterial culture, from wells below the MIC (sub-inhibitory concentration of drug) with turbidity similar to untreated control wells, was diluted 1:1000. The diluted culture was used to test the MIC of each test agent for the next passage. Plates containing bacteria and drugs were incubated at 37 °C for at least 18 hours before the MIC was determined by visual inspection. Bacteria were passaged for 14 days and resistance was characterized as a >4-fold increase in MIC relative to the initial MIC18.

Postantibiotic effect of auranofin against staphylococci

The PAE for auranofin, clindamycin, and mupirocin was determined, in duplicate, using a method described in previous studies, with the following modifications20,48. Colonies of S. aureus ATCC 6538 (FDA 209), MRSA NRS123 (MRSA USA400), and MRSA NRS384 (MRSA USA300) were transferred to separate tubes containing TSB and incubated at 37 °C with agitation at 150 rpm until the incoula reached an OD600 ~ 1.0. Bacteria were diluted 1:1000 in TSB alone (negative control) or TSB containing 5 × MIC of auranofin, clindamycin, or mupirocin (each test agent evaluated in duplicates) and incubated for one hour at 37°C with agitation at 150 rpm. After treatment with each test agent, drugs were removed by diluting each tube 1:1000 in fresh TSB and incubating at 37 °C with agitation at 150 rpm for 12 hours. Samples were collected from each tube every hour, serially diluted in PBS, and plated onto TSA. TSA plates were incubated at 37 °C for at least 18 hours to determine viable CFU. The PAE was calculated using the following equation: T – C, where T is the time required for bacterial culture treated with drug to increase by one log10 (after washout of drug) and C is the time required for the negative control to increase by one log10.

Infected pressure ulcer wound model in obese mice

This study was reviewed and approved by the Purdue University Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in strict accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Twelve-week-old female TALLYHO/JngJ mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) weighing on average 35 grams, were used for this study. Mice were housed in ventilated cages with access to water and food ad libitum. To induce infected pressure ulcers in mice, we developed a modified method to previously published reports49–52. One day prior to application of magnets, the fur along the dorsal region of mice was shaved and scrubbed with betadine solution. Thereafter, the dorsal skin just caudal to the scapulae was pinched and two 3,466 G, neodymium rare earth magnets (9.5 mm diameter × 3.2 mm thick) were placed on each side of the skin fold. Magnets were applied for ten ischemia-reperfusion cycles (two hours on, one hour off) to induce formation of moderate pressure ulcers. Mice received a subcutaneous injection of 0.03 mg/kg buprenorphine immediately before application of magnets and again every 12 hours later (during application of magnets) to minimize pain. Ulcers were infected one day after formation with 20 µL of 2.8 ×109 CFU/mL MRSA NRS384 (USA300) and covered with Tegaderm fixed with Uro-Bond IV ostomy adhesive. The infection was allowed to proceed for two days before initiating treatment. On the first day of treatment, mice were randomly divided into groups of five mice. One group of mice was treated with clindamycin orally (30 mg/kg once daily). The infected pressure ulcers for the remaining groups were treated topically twice daily with either 1% auranofin, 2% auranofin, 2% mupirocin, or the vehicle used to prepare each topical treatment (petroleum jelly). Tegaderm was applied over the wounds and fixed with Uro-Bond IV adhesive after each treatment to prevent mice from biting, scratching, or grooming the area around the wounds. Mice were checked every four hours for signs of severe morbidity (e.g. hypothermia, inability to eat or drink, or significant weight loss (>20%)). All mice were humanely euthanized 12 hours after the last dose was administered via CO2 asphyxiation and the skin tissue around each ulcer was harvested aseptically. The ulcerated tissue was homogenized in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) using an Omni Tissue Homogenizer (TH115, Omni International, Kennesaw, GA, USA). To determine the bacterial load in the ulcers, the homogenate was serially diluted and plated on mannitol salt agar plates (to select for S. aureus colonies). Plates were incubated for at least 20 hours at 37 °C before bacterial colonies were enumerated. For the two auranofin treatment groups, 1 mL of homogenate was spread over four mannitol salt agar plates and plates were incubated for 48 hours at 37 °C to confirm the absence of MRSA colonies. Data are presented as log10 (MRSA CFU) in each wound.

Statistical analysis

Data from the murine pressure ulcer experiment were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnet’s test for multiple comparisons (P < 0.05) using GraphPad Prism 8 (La Jolla, CA). To ensure the data was normally distributed, the data was subjected to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (P < 0.05).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Network of Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus (NARSA) program for providing MRSA strains used in this study. This work was supported by the NIAID/NIH [grant number R01AI130186].

Author contributions

H.M. designed and conducted the biological experiments and prepared all figures. N.S.A. assisted with conducting the mice study. H.M. wrote the main manuscript text. M.N.S. assisted with acquisition of funding, data interpretation, and editing the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP). NPUAP Pressure Injury Stages. (Washington, DC, 2016).

- 2.Beckrich K, Aronovitch SA. Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers: a comparison of costs in medical vs. surgical patients. Nurs Econ. 1999;17:263–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edsberg LE, et al. Revised National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Pressure Injury Staging System: Revised Pressure Injury Staging System. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2016;43:585–597. doi: 10.1097/WON.0000000000000281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braga IA, Pirett CC, Ribas RM, Gontijo Filho PP, Diogo Filho A. Bacterial colonization of pressure ulcers: assessment of risk for bloodstream infection and impact on patient outcomes. J Hosp Infect. 2013;83:314–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guest JF, Fuller GW, Vowden P, Vowden KR. Cohort study evaluating pressure ulcer management in clinical practice in the UK following initial presentation in the community: costs and outcomes. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021769. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato T, Abe T, Ichioka S. Factors impairing cell proliferation in the granulation tissue of pressure ulcers: Impact of bacterial burden. Wound Repair Regen. 2018;26:284–292. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norman G, et al. Antibiotics and antiseptics for pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD011586. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011586.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pressure ulcers: prevention and management of pressure ulcers. (National institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2014). [PubMed]

- 9.Capparelli, E. V., Bricker-Ford, R., Rogers, M. J., McKerrow, J. H. & Reed, S. L. Phase I Clinical Trial Results of Auranofin, a Novel Antiparasitic Agent. Antimicrob Agents Chemother61, :10.1128/AAC.01947-16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.da Silva MT, et al. In vivo and in vitro auranofin activity against Trypanosoma cruzi: Possible new uses for an old drug. Exp Parasitol. 2016;166:189–193. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harbut MB, et al. Auranofin exerts broad-spectrum bactericidal activities by targeting thiol-redox homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:4453–4458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504022112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tejman-Yarden N, et al. A reprofiled drug, auranofin, is effective against metronidazole-resistant Giardia lamblia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:2029–2035. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01675-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thangamani S, et al. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of auranofin against multi-drug resistant bacterial pathogens. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22571. doi: 10.1038/srep22571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thangamani S, Mohammad H, Abushahba MF, Sobreira TJ, Seleem MN. Repurposing auranofin for the treatment of cutaneous staphylococcal infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;47:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marzo T, et al. Auranofin and its Analogues Show Potent Antimicrobial Activity against Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens: Structure-Activity Relationships. ChemMedChem. 2018;13:2448–2454. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201800498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutherland R, et al. Antibacterial activity of mupirocin (pseudomonic acid), a new antibiotic for topical use. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;27:495–498. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.4.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Bambeke, F., Mingeot-Leclercq, M.-P., Glupczynski, Y. & Tulkens, P. M. In Infectious Diseases (Fourth Edition) (eds Jonathan Cohen, William G. Powderly, & Steven M. Opal) 1162–1180.e1161 (Elsevier, 2017).

- 18.Farrell DJ, Robbins M, Rhys-Williams W, Love WG. Investigation of the potential for mutational resistance to XF-73, retapamulin, mupirocin, fusidic acid, daptomycin, and vancomycin in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates during a 55-passage study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1177–1181. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01285-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kosowska-Shick K, et al. Single- and multistep resistance selection studies on the activity of retapamulin compared to other agents against Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:765–769. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.2.765-769.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xue IB, Davey PG, Phillips G. Variation in postantibiotic effect of clindamycin against clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus and implications for dosing of patients with osteomyelitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1403–1407. doi: 10.1128/AAC.40.6.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rittenhouse S, et al. Selection of retapamulin, a novel pleuromutilin for topical use. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:3882–3885. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00178-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyun, S. et al. Body mass index and pressure ulcers: improved predictability of pressure ulcers in intensive care patients. Am J Crit Care 23, 494–500; quiz 501, 10.4037/ajcc2014535 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight Fact Sheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (2018).

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, NCHS Data Brief, No. 288. Adult Obesity Facts. (2017).

- 25.Keogh SJ, et al. Hydrocolloid dressings for treating pressure ulcers. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018;2018:CD010364. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010364.pub2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suarez-Almazor, M. E., Spooner, C. H., Belseck, E. & Shea, B. Auranofin versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, CD002048, 10.1002/14651858.CD002048 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Weinblatt ME, et al. Low-dose methotrexate compared with auranofin in adult rheumatoid arthritis. A thirty-six-week, double-blind trial. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:330–338. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kean WF, Kean IR. Clinical pharmacology of gold. Inflammopharmacology. 2008;16:112–125. doi: 10.1007/s10787-007-0021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambers H, Piessens S, Bloem A, Pronk H, Finkel P. Natural skin surface pH is on average below 5, which is beneficial for its resident flora. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2006;28:359–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2494.2006.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.AbdelKhalek A, Abutaleb NS, Elmagarmid KA, Seleem MN. Repurposing auranofin as an intestinal decolonizing agent for vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Sci Rep. 2018;8:8353. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26674-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker RF, Luse S. The Action of Penicillin on Staphylococcus: Further Observations on the Effect of a Short Exposure. J Bacteriol. 1948;56:75–81. doi: 10.1128/JB.56.1.75-81.1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner IJ. TallyHo diabetic phenotype limited to male mice: female mice provide obese, nondiabetic mouse model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:727e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318245eaff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buck DW, 2nd, et al. The TallyHo polygenic mouse model of diabetes: implications in wound healing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:427e–437e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31822b7333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim JH, et al. Phenotypic characterization of polygenic type 2 diabetes in TALLYHO/JngJ mice. J Endocrinol. 2006;191:437–446. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peirce SM, Skalak TC, Rodeheaver GT. Ischemia-reperfusion injury in chronic pressure ulcer formation: a skin model in the rat. Wound Repair Regen. 2000;8:68–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2000.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy, P. B. & Le, J. K. Clindamycin in StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519574/ (StatPearls Publishing, 2020).

- 37.European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP), National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP) and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (PPPIA). Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/ Injuries – Quick Reference Guide (2019).

- 38.Williamson DA, Carter GP, Howden BP. Current and Emerging Topical Antibacterials and Antiseptics: Agents, Action, and Resistance Patterns. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30:827–860. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00112-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.She, P. et al. Synergistic Microbicidal Effect of Auranofin and Antibiotics Against Planktonic and Biofilm-Encased S. aureus and E. faecalis. Frontiers in Microbiology10, 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02453 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Westby MJ, Dumville JC, Soares MO, Stubbs N, Norman G. Dressings and topical agents for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD011947. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011947.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cardinal M, et al. Serial surgical debridement: a retrospective study on clinical outcomes in chronic lower extremity wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:306–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winter GD. Formation of the scab and the rate of epithelization of superficial wounds in the skin of the young domestic pig. Nature. 1962;193:293–294. doi: 10.1038/193293a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winter GD. Effect of Air Exposure and Occlusion on Experimental Human Skin Wounds. Nature. 1963;200:378–379. doi: 10.1038/200378a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winter GD, Scales JT. Effect of air drying and dressings on the surface of a wound. Nature. 1963;197:91–92. doi: 10.1038/197091b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria that Grow Aerobically, M7-A9 (ninth edition). (Wayne, PA, 2012).

- 46.Dayal, N. et al. Inhibitors of Intracellular Gram-Positive Bacterial Growth Synthesized via Povarov-Doebner Reactions. ACS Infect Dis, 10.1021/acsinfecdis.9b00022 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Mohammad H, et al. Bacteriological profiling of diphenylureas as a novel class of antibiotics against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oh, J. T., Cassino, C. & Schuch, R. Postantibiotic and Sub-MIC Effects of Exebacase (Lysin CF-301) Enhance Antimicrobial Activity against Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother63, 10.1128/AAC.02616-18 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Lanzafame RJ, et al. Preliminary assessment of photoactivated antimicrobial collagen on bioburden in a murine pressure ulcer model. Photomed Laser Surg. 2013;31:539–546. doi: 10.1089/pho.2012.3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thome Lima, M. M. C. et al. Photobiomodulation by dual-wavelength low-power laser effects on infected pressure ulcers. Lasers Med Sci, 10.1007/s10103-019-02862-w (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Swanson, E. Development of a murine model of biofilm-infected diabetic pressure ulcers M.S. thesis, Purdue University, (2013).

- 52.Wassermann E, et al. A chronic pressure ulcer model in the nude mouse. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:480–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]