Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is common and contributes to increased morbidity and mortality in people with heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).1 Pulmonary hypertension in HFpEF is initially felt to be a reflection of passive elevation in downstream pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP), but in some patients, sustained PAWP elevation leads to pulmonary vascular remodelling.2 This causes further elevation in pulmonary artery (PA) pressure that leads to development of right ventricular (RV) dysfunction and pulmonary gas exchange abnormalities, which ultimately contribute to adverse outcomes.3–7 These changes in the right heart and lungs were formerly considered to be limited to end-stage HFpEF, but recent data have revealed abnormalities in PA vasodilation and dynamic RV-PA coupling even in the earliest stages of HFpEF.8 The current evidence base is not sufficient to recommend pulmonary vascular targeting therapies for people with HFpEF,2 but novel therapies that target the PA vasculature may hold promise in this regard.

In this issue of Eur Heart J, Hoeper and colleagues provide an elegant and timely summary on the current state of the art regarding PH in HFpEF.9 The authors discuss critical knowledge gaps in classification and phenotyping in this disorder that require further study. The provocative and insightful suggestions provided help inform what should be our roadmap for the future in PH and HFpEF, while raising important unanswered questions that strike at the heart of this emerging clinical syndrome.

Pulmonary hypertension and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: What’s in a name?

The term PH agnostically refers to any elevation in hydrostatic pressure in the PA (defined as mean ≥ 25 mmHg); it tells us nothing about the mechanism.10 Pulmonary hypertension in HFpEF may be caused by high downstream PAWP, increased impedance to flow through the pulmonary vessels, or both. The former has been termed isolated post-capillary PH (IpcPH) and the latter combined post- and pre-capillary PH (CpcPH).2 As Hoeper and colleagues point out, IpcPH-HFpEF and CpcPH-HFpEF cannot be adequately distinguished based upon clinical characteristics or echocardiography alone—one needs a catheter to do this, but even then it is not agreed upon how these patients should be categorized.9 There is also a third group of patients with normal EF, high PAWP and PH that is caused by increased blood flow through the lungs.11 This rarer disorder should not be confused with the more common causes of PH discussed herein.

The term PH is sometimes confused with what used to be called PAH (pulmonary arterial hypertension), defined by high PA pressure but normal PAWP. This is now referred to as Group 1 PH according to consensus guidelines.2 Hoeper and colleagues correctly point out that Group 1 PH is a much different disorder than Ipc-PH-HFpEF, but increasing evidence suggests that it has many similarities to Cpc-PH-HFpEF.9,12–14 Along these lines, Opitz and colleagues recently identified a cohort of registry patients that meet hemodynamic criteria for Group 1 PH, but display clinical features of HFpEF (≥3 risk factors), a group they have termed as ‘atypical PAH’.12 These patients responded less well to pulmonary vasoactive therapy when compared with Group 1 PH, but better than the registry patients that met criteria for HFpEF with PH. As such, the authors suggested that ‘atypical PAH’ exists as part of a disease continuum between Group 1 PH and PH associated with HFpEF. Further support for this ‘disease continuum hypothesis’, comes from Assad and colleagues, who recently reported that subjects with Cpc-PH display genes and biological pathways in the lung known to contribute to ‘PAH’ pathophysiology.14

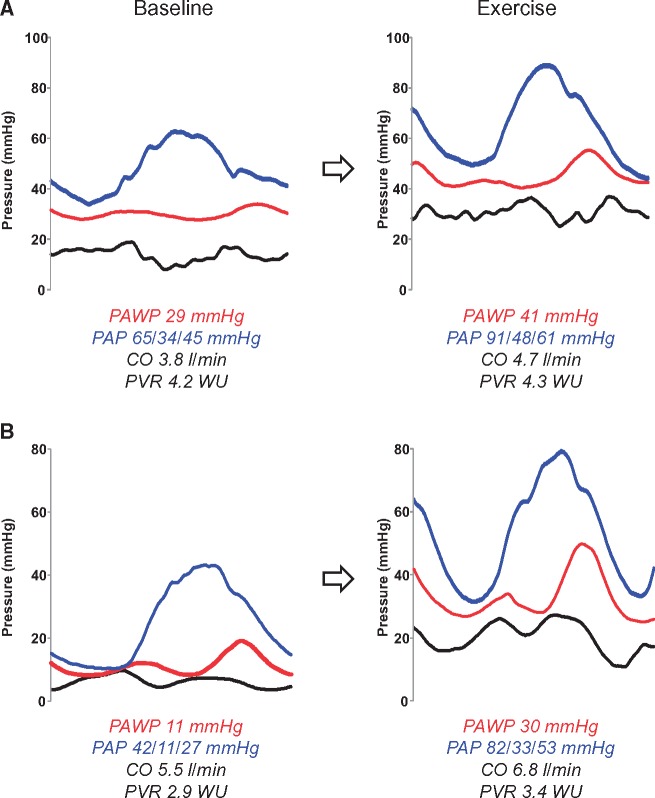

The haemodynamic feature that differentiates Group 1 PH from HFpEF is PAWP at the time of evaluation (Figure 1).2 In their review, Hoeper and colleagues state that abnormal haemodynamics support the diagnosis of HFpEF,9 but in fact haemodynamics make (or refute) the diagnosis, since that is the current gold standard test.15 Measuring an accurate PAWP requires great attention to detail, ensuring that measurements are taken at end-expiration, mid-A wave, from fluoroscopically verified PAWP position, ideally confirmed by oximetry. This is unfortunately not always accomplished in practice, and it may result in substantial misclassification. To complicate matters further, many patients with HFpEF have normal PAWP when they are assessed at rest, in a fasted, well-compensated state.8,16 If this sort of HFpEF patient had an elevated PA pressure at the time of haemodynamic assessment, they would be diagnosed as Group 1 PH (Figure 1). However, would this patient still be diagnosed as such when studied after a salty meal, or while cycling on an ergometer, where PAWP may not be normal?

Figure 1.

Haemodynamic tracings in two heart failure with preserved ejection fraction patients with pulmonary vascular disease (PVD). (A) Patient has advanced PVD, with severe elevation in pulmonary artery (PA) pressure (PAP, systolic/diastolic/mean, blue lines) that is caused by both high PA wedge pressure (PAWP, red) and elevated pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). With exercise, both PAP and PAWP increase in tandem, and there is failure of PA vasodilation (no change in PVR) as flow (cardiac output, CO) increases. (B) Patient has less advanced PVD, and based upon resting haemodynamics alone, he would be categorized as mild Group 1 pulmonary hypertension, because PAWP is normal while PAP and PVR are elevated. However, with the stress of exercise, there is dramatic elevation in PAWP, but out of proportion increase in PAP as CO rises, such that PVR actually increases, indicating that both left heart disease and PVD are present. Black lines represent right atrial pressure.

This then begs the question as to how many people are misclassified according to current diagnostic algorithms applied in the evaluation of PH. Provocative testing with either exercise or saline loading has been shown to greatly increase diagnostic accuracy for the evaluation of PH and HFpEF.15–19 While saline loading requires less equipment, it is also less sensitive, specific, and physiologically relevant when compared with exercise.17 Hoeper and colleagues point out how current guidelines have questioned the validity of provocative testing in the evaluation of PH, but what validation is really necessary? One can learn much more about the capacity of any organ system by assessing its function when stressed, whether it’s the ability of the pancreas to secrete insulin, the ability of the left ventricle to fill with blood without causing lung congestion, or the ability of the pulmonary arteries to accommodate an increase in flow without pathologic increase in pressures. The latter two questions are of particular interest for the type of patient under discussion here.

The lexicon surrounding PH in HF has become a bit of an ‘alphabet soup’. To simplify things, we might consider people with HFpEF and PH that is just caused by high PAWP as having ‘HFpEF’ (Figure 2). By removing ‘PH’, this would reinforce that PA pressures are just high owing to left heart congestion, and there are not intrinsic problems with the pulmonary vasculature. Other patients with HFpEF who also display abnormalities in PA structure and function could then be categorized as having HFpEF with pulmonary vascular disease (HFpEF-PVD). In some patients this PVD will be apparent at rest (Figure 1A) and in others it is only provoked or demonstrated with the stress of exercise (Figure 1B).8

Figure 2.

The spectrum of pulmonary hypertension in normal ejection fraction. At the ends of the spectrum there are ‘pure’ pulmonary vascular disease (Group 1 PH, green) and ‘pure’ HFpEF with no PVD (red). In between, there may be patients with PVD and some element of occult HFpEF, e.g. if PCWP is normal due to diuresis or underfilling of the left atrium (light green). There are also patients with early HFpEF and abnormal pulmonary vasodilation that is restricted to exercise (dark orange), and others with both elevated PCWP and PVD at rest and during exercise (HFpEF-PVD, light orange). In this proposed algorithm the presence or absence of PVD is defined by PVR, but further research is required to determine if this is the best metric to make this distinction, or alternatives such as PA compliance and DPG might be superior. CTEPH, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; EF, ejection fraction; Ex, exercise; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HOHF, high output heart failure; PAWP, pulmonary artery wedge pressure; PH, pulmonary hypertension; PVD, pulmonary vascular disease; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; VHD, valvular heart disease.

It is important to point out that this definition does not differentiate between PVD that is due to structural remodeling or PA vasoconstriction, and this likely has important clinical implications that require further study. Finally, patients with the type of ‘atypical PAH’ identified by Opitz and colleagues might be best evaluated with exercise testing to assess for any component of coexisting left heart disease. While this scheme may not be ready for routine clinical application, the concept of phenotyping individual patients into these mechanistically distinct and homogenous groups would serve as a starting point for prospective comparative studies, using detailed haemodynamic, imaging, clinical, and ‘omic’ assessments. One such research enterprise is already underway, being performed in the NHLBI-sponsored PVDOMICS network (NCT02980887).

Pulmonary vascular disease in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

As Hoeper and colleagues point out, there is widespread recognition that sustained PAWP elevation leads to PVD in some patients with HFpEF. However, we currently do not know to what extent the PVD observed in our patients is related to structural remodeling, PA vasoconstriction, or both. Current understandings regarding PVD in HFpEF derive from in vivo human data characterizing pulmonary hemodynamic responses in patients taken to the catheterization laboratory. This evolution is a stark contrast to conventional scientific paradigms, where initial observations originate from animal models or from human histopathology.

Histologic data supporting pulmonary vascular remodelling in HFpEF are lacking. In Group 1 PH, effacement of the distal pulmonary arteries involving the intima and media occurs, due to hypertrophic, fibrotic, plexogenic, and inflammatory vascular alterations.20 One study examined lung samples from patients with HFrEF due to coronary disease or dilated cardiomyopathy and found that medial hypertrophy of muscular pulmonary arteries was present.21 Further histopathologic study, in particular examining arteriolar, capillary and venular changes, is urgently needed to advance our understanding about the nature of PVD in HFpEF.

In contrast to Group 1 PH, specific gene mutations that promote PVD are not well understood in HFpEF. A previous study has identified shared abnormalities in PH-related signalling cascades that are common to different forms of PH, including HF subjects.22 It remains unclear whether this is due to a common pathway in disease progression or continuous spectrum of disease (Figure 2). Further studies are a major priority to improve our understanding about the pathophysiology of pulmonary vascular remodeling in HFpEF and how it is similar or different to other forms of PH.

In addition to PVD, comorbidity-related systemic vascular stiffening and endothelial dysfunction are important contributors to pathophysiology of HFpEF, and it may be that these processes also affect the RV and PA vasculature.23 In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, there are significant correlations between intimal thickness in systemic and pulmonary arteries,24 and Farrero et al. have recently observed in HFpEF that patients with more profound systemic endothelial dysfunction also displayed higher PVR, supporting this hypothesis.25

Current guidelines define the presence of PVD by either an elevation in the diastolic pressure gradient (DPG, defined as diastolic PA - PAWP) or the pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR).2 As discussed by Hoeper and colleagues, the DPG has been consistently discredited as an estimation of PVD.9 This implies that PVR may be the optimal index to distinguish these groups. However, minute increases in PVR that occur early in disease are associated with dramatic reductions in PA compliance because of the hyperbolic relationship between resistance and compliance.26 As such, PA compliance may be a more sensitive predictor of both the presence of PVD and outcomes in earlier stage patients HFpEF with PH.27

Newer indices may be even more informative. Ghimire and colleagues have recently developed a new method to characterize pulmonary vascular mechanics and more clearly delineate the importance of wave reflection in HFpEF-PVD.28 Another study from the Lewis group has shown that abnormalities in PA distensibility with exercise may be more sensitive to the presence of PVD in HFpEF while also providing a marker of adverse prognosis.29 Whatever index is ultimately chosen to define the presence of PVD, it should correlated with PVD severity, reflect changes on treatment, and predict prognosis. Further study is warranted to support use of one or more indices in this regard.

Treatment for in pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

The presence of PH is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in HFpEF, especially when there is coexisting RV dysfunction.1,4,5 Similarly, PVD itself is associated with increased mortality in HF,30–32 though fewer studies have evaluated this specifically in HFpEF-PVD.27 Imbalances in nitric oxide-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (NO-cGMP), endothelin-1, and prostacyclin signalling pathways cause elevations in PA pressures in HF.2 As reviewed by Hoeper and colleagues, efforts to restore NO-cGMP signalling with phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors have not been fruitful to date in HFpEF,9 with one notable exception amongst patients with more severe PVD.33

Recent studies examining inorganic nitrite, a novel NO-providing therapy, have demonstrated promising results in patients with HFpEF.34–36 Nitrite and nitrate were formerly considered as inert byproducts of NO metabolism, but more recent data have now shown that nitrite serves as an important in vivo reservoir for NO production. Inorganic nitrite reduces PA pressures both at rest and during exercise in HFpEF, through reductions in PAWP and improvements in PA compliance.34–36 In HFpEF patients with more dramatic PVD, it may also lower PVR.35 Clinical trials are currently underway testing this molecule in subjects with HFpEF (NCT02742129 and NCT02713126), and other trials testing agents targeted to the NO-cGMP and endothelin pathways are underway or have recently been completed.

Conclusion

Our understanding of PVD in HFpEF is still in its infancy, and many of underlying concepts in this field come from observational studies. When confronted with a newly recognized problem of this magnitude, it is tempting to have high expectations for therapies, particularly when there is strong biological plausibility and availability of potent candidate drugs. However, only through detached and disinterested inquiry will we understand the impact of characterizing and treating PVD in patients with HFpEF. Hoeper and colleagues have made a very convincing plea to the scientific community to work harder to advance our knowledge base.9 While the poor outcomes associated with this condition are sobering, they also remind us that there is an enormous opportunity to help improve the quantity and quality of life in this large and growing cohort of patients.

Conflict of interest: B.A.B. receives research funding from the NHLBI (RO1 HL128526 and U10 HL110262), Mast Therapeutics, Medtronic, GlaxoSmithKline, and Teva. B.A.B. has consulted and served on advisory boards for Actelion, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Merck and MyoKardia. M.O. has no disclosures.

References

- 1. Lam CS, Roger VL, Rodeheffer RJ, Borlaug BA, Enders FT, Redfield MM.. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a community-based study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:1119–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Galie N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, Simonneau G, Peacock A, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Beghetti M, Ghofrani A, Gomez Sanchez MA, Hansmann G, Klepetko W, Lancellotti P, Matucci M, McDonagh T, Pierard LA, Trindade PT, Zompatori M, Hoeper M, Aboyans V, Vaz Carneiro A, Achenbach S, Agewall S, Allanore Y, Asteggiano R, Paolo Badano L, Albert Barbera J, Bouvaist H, Bueno H, Byrne RA, Carerj S, Castro G, Erol C, Falk V, Funck-Brentano C, Gorenflo M, Granton J, Iung B, Kiely DG, Kirchhof P, Kjellstrom B, Landmesser U, Lekakis J, Lionis C, Lip GY, Orfanos SE, Park MH, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Revel MP, Rigau D, Rosenkranz S, Voller H, Luis Zamorano J.. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J 2016;37:67–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Melenovsky V, Andersen MJ, Andress K, Reddy YN, Borlaug BA.. Lung congestion in chronic heart failure: haemodynamic, clinical, and prognostic implications. Eur J Heart Fail 2015;17:1161–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Melenovsky V, Hwang SJ, Lin G, Redfield MM, Borlaug BA.. Right heart dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J 2014;35:3452–3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mohammed SF, Hussain I, Abou Ezzeddine OF, Takahama H, Kwon SH, Forfia P, Roger VL, Redfield MM.. Right ventricular function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a community-based study. Circulation 2014;130:2310–2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hoeper MM, Meyer K, Rademacher J, Fuge J, Welte T, Olsson KM.. Diffusion capacity and mortality in patients with pulmonary hypertension due to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2016;4:441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Olson TP, Johnson BD, Borlaug BA.. Impaired pulmonary diffusion in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2016;4:490–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Borlaug BA, Kane GC, Melenovsky V, Olson TP.. Abnormal right ventricular-pulmonary artery coupling with exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J 2016;37:3293–3302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoeper MM, Lam CSP, Vachiery JL, Bauersachs J, Gerges C, Lang IM, Bonderman D, Olsson KM, Gibbs JSR, Dorfmuller P, Guazzi M, Galie N, Manes A, Handoko ML, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Lankeit M, Konstantinides S, Wachter R, Opitz C, Rosenkranz S.. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a plea for proper phenotyping and further research. Eur Heart J 2016; doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Borlaug BA. Discerning pulmonary venous from pulmonary arterial hypertension without the help of a catheter. Circ Heart Fail 2011;4:235–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reddy YN, Melenovsky V, Redfield MM, Nishimura RA, Borlaug BA.. High-output heart failure: a 15-year experience. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:473–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Opitz CF, Hoeper MM, Gibbs JS, Kaemmerer H, Pepke-Zaba J, Coghlan JG, Scelsi L, D'alto M, Olsson KM, Ulrich S, Scholtz W, Schulz U, Grunig E, Vizza CD, Staehler G, Bruch L, Huscher D, Pittrow D, Rosenkranz S.. Pre-capillary, combined, and post-capillary pulmonary hypertension: a pathophysiological continuum . J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:368–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Assad TR, Brittain EL, Wells QS, Farber-Eger EH, Halliday SJ, Doss LN, Xu M, Wang L, Harrell FE, Yu C, Robbins IM, Newman JH, Hemnes AR.. Hemodynamic evidence of vascular remodeling in combined post- and precapillary pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ 2016;6:313–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Assad TR, Hemnes AR, Larkin EK, Glazer AM, Xu M, Wells QS, Farber-Eger EH, Sheng Q, Shyr Y, Harrell FE, Newman JH, Brittain EL.. Clinical and biological insights into combined post- and pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:2525–2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Obokata M, Kane GC, Reddy YN, Olson TP, Melenovsky V, Borlaug BA.. The role of diastolic stress testing in the evaluation for HFpEF: a simultaneous invasive-echocardiographic study. Circulation 2017;135:825–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Borlaug BA, Nishimura RA, Sorajja P, Lam CS, Redfield MM.. Exercise hemodynamics enhance diagnosis of early heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2010;3:588–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Andersen MJ, Olson TP, Melenovsky V, Kane GC, Borlaug BA.. Differential hemodynamic effects of exercise and volume expansion in people with and without heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2015;8:41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Robbins IM, Hemnes AR, Pugh ME, Brittain EL, Zhao DX, Piana RN, Fong PP, Newman JH.. High prevalence of occult pulmonary venous hypertension revealed by fluid challenge in pulmonary hypertension. Circ Heart Fail 2014;7:116–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Maor E, Grossman Y, Balmor RG, Segel M, Fefer P, Ben-Zekry S, Buber J, DiSegni E, Guetta V, Ben-Dov I, Segev A.. Exercise haemodynamics may unmask the diagnosis of diastolic dysfunction among patients with pulmonary hypertension. Eur J Heart Fail 2015;17:151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maron BA, Galie N.. Diagnosis, treatment, and clinical management of pulmonary arterial hypertension in the contemporary era: a review . JAMA Cardiol 2016;1:1056–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Delgado JF, Conde E, Sanchez V, Lopez-Rios F, Gomez-Sanchez MA, Escribano P, Sotelo T, Gomez de la Camara A, Cortina J, de la Calzada CS.. Pulmonary vascular remodeling in pulmonary hypertension due to chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2005;7:1011–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Du L, Sullivan CC, Chu D, Cho AJ, Kido M, Wolf PL, Yuan JX, Deutsch R, Jamieson SW, Thistlethwaite PA.. Signaling molecules in nonfamilial pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med 2003;348:500–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Paulus WJ, Tschope C.. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Munoz-Esquerre M, Lopez-Sanchez M, Escobar I, Huertas D, Penin R, Molina-Molina M, Manresa F, Dorca J, Santos S.. Systemic and pulmonary vascular remodelling in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PloS One 2016;11:e0152987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Farrero M, Blanco I, Batlle M, Santiago E, Cardona M, Vidal B, Castel MA, Sitges M, Barbera JA, Perez-Villa F.. Pulmonary hypertension is related to peripheral endothelial dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2014;7:791–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tedford RJ, Hassoun PM, Mathai SC, Girgis RE, Russell SD, Thiemann DR, Cingolani OH, Mudd JO, Borlaug BA, Redfield MM, Lederer DJ, Kass DA.. Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure augments right ventricular pulsatile loading. Circulation 2012;125:289–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Al-Naamani N, Preston IR, Paulus JK, Hill NS, Roberts KE.. Pulmonary arterial capacitance is an important predictor of mortality in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2015;3:467–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ghimire A, Andersen M, Burrowes LM, Bouwmeester JC, Grant AD, Belenkie I, Fine NM, Borlaug BA, Tyberg JV.. The reservoir-wave approach to characterize pulmonary vascular-right ventricular interactions in man. J Appl Physiol 2016;121:1348–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Malhotra R, Dhakal BP, Eisman AS, Pappagianopoulos PP, Dress A, Weiner RB, Baggish AL, Semigran MJ, Lewis GD.. Pulmonary vascular distensibility predicts pulmonary hypertension severity, exercise capacity, and survival in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2016;9:e003011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dupont M, Mullens W, Skouri HN, Abrahams Z, Wu Y, Taylor DO, Starling RC, Tang WH.. Prognostic role of pulmonary arterial capacitance in advanced heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2012;5:778–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gerges C, Gerges M, Lang MB, Zhang Y, Jakowitsch J, Probst P, Maurer G, Lang IM.. Diastolic pulmonary vascular pressure gradient: a predictor of prognosis in “out-of-proportion” pulmonary hypertension. Chest 2013;143:758–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miller WL, Grille DE, Borlaug BA.. Clinical features, hemodynamics, and outcomes of pulmonary hypertension due to chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2013;1:290–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guazzi M, Vicenzi M, Arena R, Guazzi MD.. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a target of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition in a 1-year study. Circulation 2011;124:164–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Borlaug BA, Koepp KE, Melenovsky V.. Sodium nitrite improves exercise hemodynamics and ventricular performance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:1672–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Borlaug BA, Melenovsky V, Koepp KE.. Inhaled sodium nitrite improves rest and exercise hemodynamics in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Res 2016;119:880–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Simon MA, Vanderpool RR, Nouraie M, Bachman TN, White PM, Sugahara M, Gorcsan J 3rd, Parsley EL, Gladwin MT.. Acute hemodynamic effects of inhaled sodium nitrite in pulmonary hypertension associated with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JCI Insight 2016;1:e89620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]