Abstract

Retention in preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) care is critical to elimination of human immunodeficiency virus. We reviewed all Howard Brown Health patients receiving PrEP (n = 5583) from 2012 to 2017. Among those with 12 months of follow-up, 43% remained in care, yet only 15% had all 4 quarters with a PrEP visit. Insurance status and comorbid conditions were drivers of retention in care.

Keywords: pre-exposure prophylaxis, men who have sex with men, retention in care

Retention in PrEP care is critical to elimination of human immunodeficiency virus. We reviewed all Howard Brown Health patients receiving PrEP (n = 5583) from 2012 to 2017. Among those with 12 months of follow-up, 43% remained in care, yet only 15% had all 4 quarters with a PrEP visit. Insurance status and comorbid conditions were drivers of retention in care.

Retention in preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) care is a critical step in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) preventive care continuum [1] and a cornerstone to maximizing PrEP efficacy. Most PrEP retention in care findings have been generated from placebo-controlled and open-label studies [2–4], which may not reflect retention in real-world routine PrEP care. These projects may not be representative owing to differences in populations enrolled, use of incentives, and deployment of other nonroutine care practices that maintain contact with patients or bypass complex insurance systems to provide medication at no cost to the patient.

Although these studies demonstrated high retention rates, we know very little about individuals who are not retained and have limited information on racial and ethnic minorities, and there continues to be a paucity of information on longer-term retention, beyond 12 months. A study in 3 cities demonstrated suboptimal adherence at 6 months, intermittent retention among African Americans and 3 seroconversions, not related to drug failure [5]. Promising reports of zero HIV transmission events in Northern California are of interest [6]; however, we do not know patterns of retention and what patient-level factors were associated with retention in care.

Although it is possible that eligible persons retained in care may find a provider who is willing to prescribe PrEP without an HIV test, or infrequent sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing, current recommendations do not support this practice; as such, those experiencing retention in care failure are probably not receiving PrEP and are thus at greater risk for seroconversion. Improved retention in PrEP care is likely to have a number of additional health benefits, ranging from routine STI testing, screening for and treatment of other comorbid conditions to treatment of mental health and other substance use disorders. The purpose of the analysis presented here is to provide descriptive information on retention in care patterns in routine clinical care and to explore some of the baseline factors related to retention that may inform clinical practice, mathematical models, and future retention in PrEP care prevention interventions.

METHODS

Study Setting

Howard Brown Health (HBH), with a network of 6 clinical sites, is inclusive of a large sexual and gender minority patient base, with 20671 active patients in 2016. HBH has Federally Qualified Health Center status, with clinics located in diverse community areas and with 2 new clinics opened in 2016 on the South Side of the city in one of Chicago’s major HIV epicenters. Since 2012, HBH has been one of the leading PrEP prescribers in the country. PrEP has been provided to existing primary care patients and those presenting for care.

Eligibility and Patient-Level Measures

Data were reviewed in the electronic health record for all patients starting PrEP from January 2012 through December 2017. PrEP initiation was defined as any patient visiting a HBH provider where tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine monotherapy was prescribed and without a diagnosis of HIV at the prescribing event or with other antiretrovirals started on the same day. Other patients excluded were those receiving postexposure prophylaxis and those with hepatitis B in whom tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine monotherapy was prescribed, unless postexposure prophylaxis administration or hepatitis B infection occurred after an initial PrEP visit.

A sample of charts were reviewed (n = 100) to validate the case definition and ongoing audits of any new infections during PrEP were performed. Variables abstracted from the electronic health record also included, age, sex assigned at birth, current gender identity, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, residence, baseline and follow-up syphilis, gonorrhea/chlamydia (a potential proxy for sexual risk), and hepatitis B testing and results, patient visit history before PrEP initiation, prior comorbid conditions (including depression, anxiety, other mental illnesses, trauma, sexual assault, alcohol use, diabetes, endocrine disorder [not otherwise specified], hypertension, asthma, and HIV exposure), and dates of initial and follow-up clinic visits.

Retention in Care Measures

Retention in PrEP care does not have a standard definition. Most research and implementation analyses have examined PrEP retention in care as remaining in PrEP care by 6 months [7]. Retention has many facets, and several measures have been proposed for HIV care [8]. Although there are critical differences between retention in PrEP and retention in HIV care, retention in HIV care has well-established retention metrics, with varying performances [9]. Because PrEP retention measures have not been validated, we use the metric that focuses on regular consecutive intervals—visit constancy—given existing guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [10] that support visits every 3 months with a PrEP provider. Although visit constancy is more computationally challenging than other retention in care metrics, its advantages include that it better accounts for loss to follow-up than missed visits or adherence measures, is amenable to analyses that compare exposures and outcomes, and can be applied to longer time periods. We use visit constancy as the primary retention in care measure.

Analyses

Bivariate and multivariate analyses were performed in the subset of individuals who had the potential for 12 months of follow-up (PrEP started 31 December 2016 or earlier). We used χ2 tests to assess the bivariate associations of potential predictors with the outcome of visit constancy. Variables associated at P ≤ .2 were selected to be included in final models. A multinomial regression was built beginning with all associated predictors and reduced using backward selection, removing 1 variable at a time based on P value. Variables identified a priori to be controlled for based on the conceptual framework were age, race, gender, year of PrEP initiation, and the patient’s status as an existing client of the healthcare center. Retention in care models were conducted for those with ≥12 months of follow-up. Data management was performed with SAS 5.1 software, and analysis with Stata 11 software. All analyses were approved by 2 separate institutional review boards.

RESULTS

Overall, 5583 individuals started PrEP from January 2012 through December 2017. Those included in the primary analysis were limited to individuals who started PrEP on 31 December 2016 or earlier (n = 3451), to allow for 12 months of follow-up for each individual. This analytic group accumulated 4523 person-years of PrEP use.

Characteristics of the analytic sample can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Starting Preexposure Prophylaxis at Howard Brown Health (n = 3451), 2012–2016

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |

| Age, y | |

| <18 | 8 (0.2) |

| 18–24 | 749 (21.7) |

| 25–29 | 975 (28.3) |

| 30–34 | 675 (19.6) |

| 35–39 | 397 (11.5) |

| 40–49 | 448 (13.0) |

| ≥50 | 199 (5.8) |

| Gender identity | |

| Cis male | 3175 (92.0) |

| Cis female | 65 (1.9) |

| Transfemale | 161 (4.7) |

| Transmale | 41 (1.2) |

| Gender nonconforming | 8 (0.2) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.03) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 1977 (57.9) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 536 (15.5) |

| Hispanic | 670 (19.4) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 194 (5.6) |

| Unknown | 54 (1.6) |

| MSM | |

| Gay cis male | 2734 (79.2) |

| Bisexual cis male | 225 (6.5) |

| Queer or something else cis male | 116 (3.4) |

| Non-MSM | 376 (10.9) |

| Residence | |

| Chicago | 2896 (83.9) |

| Non-Chicago | 555 (16.1) |

| Insurance | |

| Private insurance | 2061 (59.7) |

| Medicaid or Medicare | 646 (18.7) |

| Uninsured | 744 (21.6) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Previous PEP | |

| No PEP ever | 2914 (84.4) |

| PEP before PrEP | 537 (15.6) |

| No. of comorbid conditionsa | |

| 0 | 356 (10.3) |

| 1 | 1923 (55.7) |

| 2 | 753 (21.8) |

| ≥3 | 419 (12.1) |

| No. of mental health conditions | |

| 0 | 2561 (74.2) |

| 1 | 712 (20.6) |

| ≥2 | 178 (5.2) |

| Syphilis baseline | |

| No test | 426 (12.3) |

| Negative | 2813 (81.5) |

| Positive | 212 (6.1) |

| Gonorrhea/chlamydia baseline | |

| No test | 224 (6.5) |

| Negative | 2700 (78.2) |

| Positive | 527 (15.3) |

| Hepatitis B baseline | |

| No test | 946 (27.4) |

| Immune | 2041 (59.4) |

| Susceptible | 278 (8.1) |

| Active or evolving infection | 5 (0.1) |

| Unknown | 181 (5.2) |

| Existing HBH patient | |

| No prior diagnoses | 997 (28.9) |

| Any prior diagnosis | 2454 (71.1) |

| PrEP-related outcomes | |

| Monthly unique PrEP starts | |

| 2012 | 2 (0.6) |

| 2013 | 5 (1.8) |

| 2014 | 46 (16.1) |

| 2015 | 93 (32.3) |

| 2016 | 141 (49.2) |

| STI positive after PrEP initiation | |

| No test | 434 (12.6) |

| Negative | 1404 (40.7) |

| Positive | 1613 (46.7) |

| Seroconversion (12 mo) | |

| No seroconversion | 3406 (98.7) |

| Seroconversion | 45 (1.3) |

| 12-mo Visit constancya | |

| No follow-up | 543 (15.7) |

| Quarters with follow-up | |

| 1/4 | 700 (20.3) |

| 2/4 | 824 (23.9) |

| 3/4 | 856 (24.8) |

| 4/4 | 528 (15.3) |

| 12-mo Follow-up | |

| No follow-up | 543 (15.7) |

| No follow-up after 3 mo | 371 (10.8) |

| No follow-up after 6 mo | 358 (10.4) |

| No follow-up after 9 mo | 689 (20.0) |

| Remains in care at 12 mo | 1490 (43.2) |

| Visit HRSA measure | |

| No visits separated by ≥3 mo | 1342 (38.9) |

| ≥2 Visits separated by ≥3 mo | 2109 (61.1) |

Abbreviations: HBH, Howard Brown Health; HRSA, Health Resources and Services Administration; MSM, men who have sex with men; PEP, postexposure prophylaxis; PrEP, preexposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

aAmong patients eligible for 12 months of follow-up.

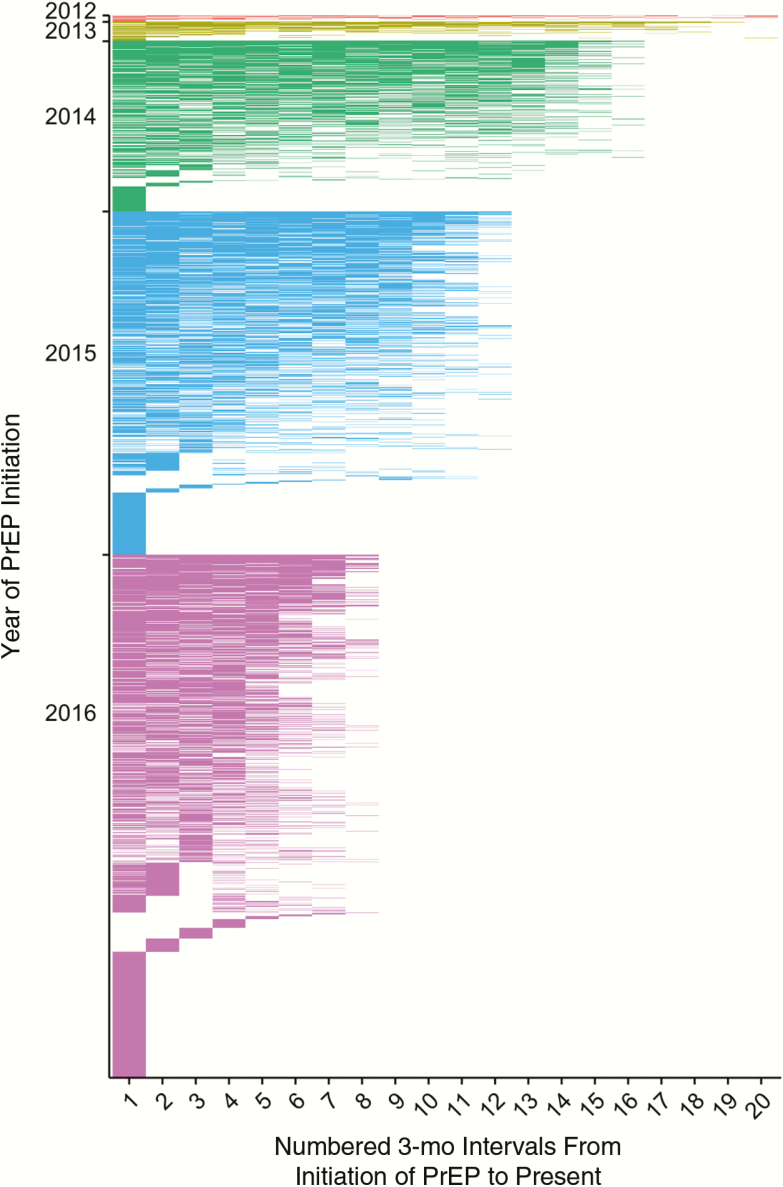

There were approximately 141 monthly PrEP starts in 2016; 1066 (61%) of clients starting PrEP in 2015 or earlier have been receiving PrEP for ≥24 months, 1613 (47%) had an STI during follow-up (12% with syphilis, 31% with gonorrhea, and 30% with chlamydia), and 34% had ≥2 other clinical diagnoses at PrEP initiation. With respect to PrEP retention in care, just under half (43%) were retained in care for ≥12 months, yet only 15% had high visit constancy (clinic visit in all 4 quarters) consistent with CDC guidelines [10] during the first 12 months of PrEP care. Figure 1 depicts the pattern of visit constancy among clients over the 5-year time frame. In final multinomial regression models, factors associated with PrEP visits in ≥1 quarter included the number of other comorbid conditions (adjusted odds ratio for 1 comorbid condition, 1.73 [95% confidence interval, 1.26–2.37]; 2 comorbid conditions, 1.99 [1.31–3.03]; and ≥3 comorbid conditions, 3.20 [1.73–5.90]). In addition, with higher visit constancy of 3 of 4 or 4 of 4 quarters with a PrEP visit, uninsured clients were less likely to be retained in care (adjusted odds ratio, 0.38 [95% confidence interval, .28–.52] and 0.43 [.30–.62], respectively).

Figure 1.

Heat map of retention in care after preexposure prophylaxis initiation at Howard Brown Health in Chicago, Illinois (July 2012 to December 2016; n = 3451). Each row represents a unique patient. Each color represents a calendar year. Abbreviation: PrEP, preexposure prophylaxis.

DISCUSSION

We present several important findings from one of the largest in routine care PrEP cohorts that illuminate natural trajectories of PrEP retention in care within a domestic HIV epicenter. First, we find that overall PrEP retention falls short of CDC guidelines [10], which recommend 3-month visit constancy. A fundamental question based on these data is whether the current schedule is too stringent for this younger sexual and gender minority (and particularly male) clinic population. It is unclear whether low rates of retention are due to the need for longer gaps between scheduled visits for adherent patients, whether risk and perception of risk are dynamic, or whether social and structural factors are impeding clinic visits.

Second, we find that baseline comorbid conditions were associated with increased visit constancy over time. This is significant given the interest in integrating PrEP care with other routine clinical care for younger sexual and gender minority populations. Third, we find that retention in care at high levels, such as making 3 of 4 quarters or a perfect 4 of 4 quarters, was lower among the uninsured, suggesting that consistent insurance coverage [11] is critical when considering high levels of retention in care, in line with existing guidelines. Notably, though we did find similar low retention rates overall, as in prior studies, we did not see any differences in retention by race/ethnicity or age. In addition, retention in PrEP care was not associated with having a diagnosed STI, suggesting that individuals who are retained in care are not retained owing to behaviors associated with STIs. Finally, this sample includes the largest group of transgender and gender-nonconforming persons reported to date, and we did not find any differences in PrEP retention by gender status.

Our finding that having additional clinical diagnoses was highly associated with retention in care suggests that many clients may need additional reasons for visiting their healthcare provider other than PrEP. Follow-up in the form of other health and well-being visits seems to be important, and PrEP care can become integrated into those visits. Interestingly, specific comorbid conditions, such as STIs, mental health issues, and substance use were not associated with retention in care; rather, it was the total number of diagnoses that was associated. In addition, comorbid conditions at the first PrEP prescription were significant, and these were associated with retention in care irrespective of whether the patient was an existing clinic patient when PrEP was prescribed or was new to the clinic. We do not know whether the association between a higher number of comorbid conditions and increased retention is driven by the provider, the patient, or both.

Our finding that insurance is important for longer-term PrEP retention underscores the benefits of healthcare coverage for office visits and laboratory tests that are typically not covered by pharmaceutical or other publicly funded PrEP benefit programs. Another study did not find insurance status or medication costs to be associated with PrEP maintenance; however, the follow-up period was short, at 6 months [5]. Similar to this study, we also found a limited association between insurance status and making 2 visits annually, but for more consistent visits over longer periods of time, our findings suggest that insurance status is an important factor in longer-term retention in PrEP care.

Within a larger context, this work is conducted in the setting of significant gaps in existing programs for PrEP retention in care. Although the HIV treatment literature suggests many strategies to retain HIV-infected persons in care, PrEP care is not comparable, given that retention in care may be a function of dynamic sexual risks, and adoption of HIV retention in care interventions is unwarranted. In the PrEP context, it is unclear whether low rates of retention are due to a need for longer gaps between scheduled visits for adherent patients, whether risk and perception of risk are dynamic, or whether social and structural factors are impeding clinic visits. In addition, the relationship between STIs, sexual behavior and PrEP use needs further investigation.

Future work must further unpack the reasons for failure of retention in care. Interventions for PrEP will need to carefully determine the individual reasons behind failed clinic visits, differentially engage patients based on their dynamic behavior, and assess for other structural factors that may impede retention in care. Thus, identifying clients at risk for retention failure, including those without any other comorbid conditions or the uninsured, is critical to PrEP implementation and ongoing HIV elimination efforts.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the Howard Brown Health preexposure prophylaxis client navigation and healthcare provider teams for their work in implementing comprehensive PrEP care.

Financial support. This work was supported in part by grants R34 MH11139201 (NIMH), R01 DA039934 (NIDA) and the NIH-funded Third Coast Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) (P30 AI117943).

Potential conflicts of interest. L. K. R.’s institution receives some salary support for salary paid to her from the Gilead Focus Grant through November 2017. K. K. has received payment for lectures including services on speakers bureaus from Gilead and Merck for human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus programs. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. McNairy ML, El-Sadr WM. A paradigm shift: focus on the HIV prevention continuum. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59(suppl 1):S12–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. ; iPrEx Study Team Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:2587–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grant R, Anderson P, McMahan V, Liu A, Amico K, Mehrotra M. Results of the iPrEx open-label extension (iPrEx OLE) in men and transgender women who have sex with men: PrEP uptake, sexual practices, and HIV incidence. Presented at: 20th International AIDS Conference; 2014; Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Bacon O, et al. High interest in preexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men at risk for HIV infection: baseline data from the US PrEP demonstration project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015 Apr 1; 68:439–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chan PA, Mena L, Patel R, et al. Retention in care outcomes for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation programmes among men who have sex with men in three US cities. J Int AIDS Soc 2016; 19:20903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, et al. No new HIV infections with increasing use of HIV preexposure prophylaxis in a clinical practice setting. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:1601–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hosek SG, Rudy B, Landovitz R, et al. ; Adolescent Trials Network (ATN) for HIVAIDS Interventions An HIV preexposure prophylaxis demonstration project and safety study for young MSM. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017; 74:21–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mugavero MJ, Davila JA, Nevin CR, Giordano TP. From access to engagement: measuring retention in outpatient HIV clinical care. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2010; 24:607–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mugavero MJ, Westfall AO, Zinski A, et al. ; Retention in Care (RIC) Study Group Measuring retention in HIV care: the elusive gold standard. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 61:574–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2014 clinical practice guidelines. Atlanta GA: CDC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marks SJ, Merchant RC, Clark MA, et al. Potential healthcare insurance and provider barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis utilization among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017; 31:470–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]