Abstract

Regenerative pain medicine, which seeks to harness the body’s own reparative capacity, is rapidly emerging as a field within pain medicine and orthopedics. It is increasingly appreciated that common analgesic mechanisms for these treatments depend on neuroimmune modulation. In this Review, we discuss recent progress in mechanistic understanding of nociceptive sensitization in chronic pain with a focus on neuroimmune modulation. We also examine the spectrum of regenerative outcomes, including preclinical and clinical outcomes. We further distinguish the analgesic mechanisms of regenerative therapies from those of cellular replacement, creating a conceptual and mechanistic framework to evaluate future research on regenerative medicine.

While acute pain brings attention to injuries, chronic pain has no biological benefits. Chronic pain often arises from disease (e.g., arthritis, cancer) and trauma (e.g., nerve injury, spinal cord injury); it affects up to 30% of adults worldwide and costs the US economy more than $600 billion per year (1, 2). Arthritis alone affects more than 53 million individuals in the US (3), and current nonsurgical therapies have limitations due to low efficacy and side effects, such as steroid injections (4), hyaluronic acid (HA) viscosupplementation (5), and opioid therapy (6). Novel approaches to treating arthritis and other common painful conditions (e.g., back and neck injury, neuropathic pain) are critically needed. One of these advances, the field of regenerative pain therapies, seeks to harness the body’s own reparative capacity, and is built on our improved understanding of the neurobiologic mechanisms that mediate and modulate pain perception and sensitization, coupled with our understanding of how inflammatory processes impact dynamic “pain circuits.” Here, we discuss recent advances in research areas that are mechanistically related to regenerative pain medicine.

Primary afferent pathways that contribute to pain perception and sensitization

Specialized sensory neurons called nociceptors sense pain by detecting noxious stimuli (7–9). Nociceptor sensitization (or peripheral sensitization) may be the most direct cause of pathological or persistent pain (10) and the most appropriate target for peripheral regenerative therapies. Nociceptors are characterized by wide molecular and functional diversity, comprising both unmyelinated C-fibers and myelinated Aδ-fibers as the largest population of primary sensory neurons in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG), trigeminal ganglion, and glossopharyngeal ganglion. In addition to noxious thermal, mechanical, and chemical stimuli, light can also induce or suppress pain when nociceptors express light-sensing ion channels (11). Using transcriptional profiling analysis at the whole-population and single-cell levels, Chiu et al. revealed molecular diversity within six distinct groups of mouse DRG neurons (12). Usoskin et al. used unbiased single-cell RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), revealing 11 types of mouse DRG neurons (3574 ± 2010 genes per cell), including three low-threshold mechanoreceptive, two proprioceptive, and six principal types of nociceptive neurons (13). Using high-coverage single-cell RNA-Seq (10,950 ± 1218 genes per neuron) with functional characterization, Li et al. identified 10 types and 14 subtypes of mouse DRG neurons (14). Deep sequencing of eight DRG neuron subtypes using individual mouse genetic lines revealed differentially expressed and functionally distinct genes, including the voltage-gated potassium channels Kv1–Kv4 (15).

Recent work has generated human nociceptors by reprograming fibroblasts; this technique recapitulated some aspects of human disease phenotypes in vitro to model “pain in a dish” (16). Humans and mice display some key differences in gene expression and function of DRG neurons (17, 18): human DRGs have higher expression of Nav1.7 (19), a sodium channel subtype critical for normal and abnormal pain sensation in humans (20, 21). Nav1.7 expression and function are upregulated in rodent and human DRG neurons by paclitaxel, a chemotherapy drug that induces neuropathy in rodents and humans (19, 22), as well as in DRG neurons of patients with neuropathic pain (22).

Touch hypersensitivity or tactile allodynia is a common feature of acute and chronic pain (23). Low-threshold Aβ-fiber neurons express Tlr5 (13, 15), and recent evidence suggests that pharmacological inhibition of these neurons blocks mechanical allodynia (24). Interestingly, in both mice and humans, application of the TLR5 ligand flagellin onto primary afferent neurons results in increased membrane permeability to QX-314, a membrane-impermeable lidocaine derivative, and subsequent silencing of TLR5-expressing A-fibers, without affecting the function of C-fibers (24). Moreover, a combination of flagellin and QX-314 blocked Aβ-fiber–evoked compound potentials in the sciatic nerve (24), Aβ-fiber–evoked synaptic transmission in spinal cord neurons (25), and mechanical allodynia in mice after nerve injury and chemotherapy (24). In contrast, C-fiber blockade with capsaicin/QX-314 (26) inhibited heat hyperalgesia after nerve injury without affecting mechanical allodynia after chemotherapy (24).

Notably, single-cell RNA-Seq may miss certain low-expression but important genes in sensory neurons. For example, the autism-associated gene Shank3 is not detected by single-cell analysis (13), but is indeed present in DRG neurons. SHANK3 loss in sensory neurons results in decreased heat sensitivity but increased mechanical sensitivity (27, 28). Thus, SHANK3 expression in sensory neurons contributes to pain and touch dysregulation in autism patients (27, 28). Partial knockdown of SHANK3 with siRNA is sufficient to block the capsaicin response and TRPV1 function in human DRG neurons (27). Programmed death protein-1 (PD-1, encoded by Pdcd1) is typically expressed by immune cells and serves as a target of immune therapy for cancer (29). Electrophysiological studies revealed that functional PD-1 is present in both mouse and human DRG neurons, and its activation by the ligand PD-L1 silences nociceptive neurons (30). Behavioral studies further demonstrate that PD-L1/PD-1 signaling inhibits physiological and pathological pain in mice (30). In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry showed Pdcd1/Pd1 mRNA expression and PD-1 protein expression in mouse DRG neurons (30), although single-cell RNA-Seq failed to detect Pdcd1 mRNA expression (13). Together, these findings suggest that PD-L1/PD-1 may act as an endogenous inhibitory system for pain (30).

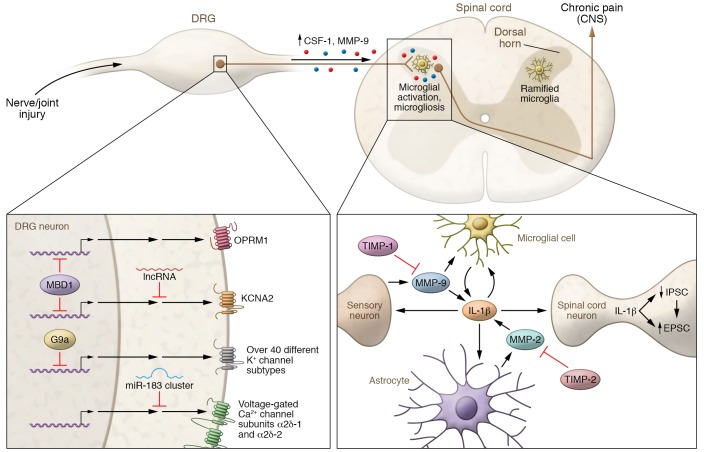

Accumulating evidence suggests an important role for epigenetic regulation of gene expression in primary sensory neurons for the pathogenesis of pain (Figure 1). Methyl-CpG–binding domain protein 1 (MBD1), an epigenetic repressor, regulates neuropathic pain by suppressing μ-opioid receptor (Oprm1) and potassium channel Kv1.2 (encoded by Kcna2) expression in primary sensory neurons (31). A long noncoding RNA that induces neuropathic pain by silencing Kcna2 was also identified in primary afferent neurons (32). In DRG neurons, nerve injury increased the activity of euchromatic histone-lysine N-methyltransferase-2 (G9a), which drives neuropathic pain via epigenetic silencing of potassium channels (33). Furthermore, mechanical allodynia in neuropathic pain is controlled by sensory neuron expression of the microRNA-183 (miR-183) cluster, which regulates the expression of voltage-gated calcium channel subunits α2δ-1 and α2δ-2; these subunits are the molecular targets of gabapentin, a common treatment for neuropathic pain (34). Sensory neurons also express histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) after chemotherapy, and HDAC6 activation results in mechanical allodynia and a loss of intraepidermal nerve fibers (35).

Figure 1. Pathogenesis of neuropathic pain and arthritic pain via gene regulation in DRG neurons and neuroinflammation in the spinal cord.

Lower left: Epigenetic regulation in DRG neurons in peripheral sensitization after nerve injury. In primary sensory neurons, MBD1 epigenetically suppresses expression of μ-opiod receptor and potassium channel subtype Kv1.2 (encoded by Kcna2). Kcna2 expression is also silenced by long noncoding RNA (lncRNA). Activity of G9a in DRG neurons increases following nerve injury, resulting in epigenetic silencing of more than 40 potassium channel subtypes. Voltage-gated calcium channel subunits α2δ-1 and α2δ-2, the molecular targets of gabapentin, are regulated by the miR-183 cluster. Right: Spinal cord microglia activation in chronic pain. Nerve injury and joint injury induce upregulation of MMP-9 and CSF-1 in DRG neurons. MMP-9 and CSF-1 undergo axonal transport to the spinal cord dorsal horn. Upon release, MMP-9 and CSF-1 induce microglia activation (e.g., p38 phosphorylation) and microgliosis (proliferation and morphological changes) in the ipsilateral spinal cord, leading to the development of chronic pain. Lower right: Spinal cord neuroinflammation in central sensitization and chronic pain. Upon activation, microglia produce and release IL-1β, which induces central sensitization and chronic pain via both presynaptic and postsynaptic regulations, leading to increased EPSCs and decreased IPSCs. IL-1β also modulates the activation of microglia and astrocytes in the spinal cord. Delayed but persistent MMP-2 production in astrocytes contributes to late-phase neuropathic pain. Both MMP-9 and MMP-2 are involved in regulating the cleavage and activation of IL-1β. Inhibition of MMP-9 and MMP-2 by TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 blocks neuropathic pain.

Neuro-immune interactions and neuroinflammation in chronic pain

The past decade has also seen substantial progress in revealing non-neuronal mechanisms of pain (36, 37). Bidirectional signaling between the immune and nervous systems contributes to the development and maintenance of chronic pain (38–40). Microarray studies show that after nerve injury, immune-related genes are among the most differentially regulated genes in the spinal cord (41). Moreover, transcripts correlating with tactile hypersensitivity are immune cell–centric; depletion of macrophages or T cells reduced neuropathic tactile allodynia but not cold hypersensitivity (42). Neuroinflammation is local, resulting from glia activation in the PNS (e.g., Schwann cells and satellite glial cells) and the CNS (e.g., microglia and astrocytes), as well as from the activation and infiltration of immune cells (e.g., macrophages and T cells) (43–45). While neuroinflammation in the PNS drives peripheral sensitization, neuroinflammation is also implicated in central sensitization, widespread chronic pain, and comorbidities, such as fibromyalgia and temporomandibular disorders (46). Central sensitization, which is mediated by the enhancement of pain processing within the spinal cord and brain, manifests as an increase in excitatory neurotransmission and/or disinhibition, i.e., reduction or loss of inhibitory synaptic transmission in CNS pain circuits (47). Central sensitization opens the spinal cord “gate,” rendering low-threshold Aβ-fiber stimulation such as light touch sufficient to induce mechanical allodynia (48).

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are extracellular matrix proteins with major roles in neuroinflammation and pathological pain (49) (Figure 1). The gelatinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 are among the most studied MMP-s and contribute to the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain in mice (50). Nerve axonal injury induces a rapid but transient increase in MMP-9 expression and activity in DRG neurons. Secreted MMP-9 activates microglia, leading to early-phase neuropathic pain. Intrathecal injection of MMP-9 is sufficient to evoke persistent mechanical allodynia and p38 phosphorylation in spinal microglia, a critical event of microglial signaling in pathological pain (51–53). MMP-9 has also been observed to be upregulated in the synovial fluid of patients with joint fracture (54). Nerve injury also causes delayed but persistent MMP-2 production in glial cells, leading to late-phase neuropathic pain mediated by ERK phosphorylation in astrocytes (51), a critical event for astrocyte activation during the maintenance of neuropathic pain (55). Tissue inhibitor of MMPs (TIMP) proteins, endogenous MMP inhibitors with relative selectivity of TIMP-1 for MMP-9 and TIMP-2 for MMP-2, suppress neuropathic pain in different phases: TIMP-1 alleviates early-phase neuropathic pain, and TIMP-2 attenuates late-phase neuropathic pain (51). Mice lacking TIMP-1 exhibited rapid onset of thermal and mechanical hypersensitivity at the site of inflammation (56). Genetic pathway analysis revealed a major role for extracellular matrix organization in inflammatory and neuropathic pain (57).

MMP-9 and MMP-2 are involved in IL-1β activation and signaling in neuropathic pain (51). The proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β induces pain hypersensitivity in rodents by increasing nociceptor excitability and modulating spinal synaptic transmission through neuronal receptors (58, 59). In particular, IL-1β powerfully modulates both excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission in the spinal dorsal horn (Figure 1). At the presynaptic level, IL-1β increases NMDA receptor activity and inhibits the frequency of spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) in the spinal pain circuit (59, 60). At postsynaptic and extrasynaptic sites, IL-1β reduces the IPSC amplitude and GABA- and glycine-induced currents (59, 61). In contrast, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra), which opposes the actions of IL-1β, is downregulated in chronic pain conditions (62). IL-1β release results from NLRP3 inflammasome activation and is associated with enhanced neuropathic pain after chronic opioid exposure (63).

TGF-β1, an antiinflammatory cytokine, is downregulated in chronic pain conditions in both animals (64) and patients (65). TGF-β1 is a potent inhibitor of neuropathic pain, and has been shown to suppress spinal cord glial activation and neuroinflammation after nerve injury (66, 67). In addition to canonical signaling through gene transcription, TGF-β1 plays an unconventional role in neuromodulation in the DRG: it can rapidly activate TGF-β1 receptors on neurons, normalizing nerve injury–induced DRG neuronal hyperexcitability and spinal cord synaptic plasticity within minutes (66). Interestingly, TGF-β1 is a target of miR-30c-5p, which is increased in the spinal cord, DRG, cerebrospinal fluid, and plasma after sciatic nerve injury in rats (68). TGF-β1 is downregulated by miR-30c-5p and upregulated by miR-30c-5p inhibitor after nerve injury.

IL-10 is probably the best-studied antiinflammatory cytokine in pain research. In early life, neuropathic pain after nerve injury is constitutively suppressed by IL-10–mediated antiinflammatory neuroimmune regulation in the mouse spinal cord (69). Gene therapy via enhancement of endogenous production of IL-10 produces long-term relief of neuropathic pain in rats (70). Endogenous IL-10 is also implicated in pain relief by exercise (71), acupuncture (72), and CD8+ T cell transplantation (73) in rodent models of neuropathic and muscle pain. Mechanistically, IL-10 suppresses abnormal paclitaxel-induced spontaneous discharges in DRG neurons in vitro (73). Infant nerve injury also triggers upregulation of another antiinflammatory cytokine, IL-4, which is correlated with lack of neuropathic pain in early life in mice (69). By contrast, nerve injury decreases spinal IL-4 levels in adult mice, and IL-4 mediates the analgesia produced by low-intensity exercise in neuropathic pain (74).

Resolution of inflammation requires the production of specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs) (e.g., resolvins, maresins, and protectins), which are derived from omega-3 unsaturated fatty acids such as docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid (75), during the resolution phase of inflammation. Notably, resolvin D1 is induced after sham surgery, a resolution condition that is associated with acute inflammation and acute pain in mice (76). SPMs not only possess potent antiinflammation and pro-resolution actions but also produce powerful antinociception via both immunomodulation and neuromodulation (75, 77). For example, resolvin E1 inhibits inflammatory pain in mice in part by blocking TRPV1 signaling in nociceptors via its G protein–coupled receptor ChemR23 (77).

Tremendous progress has been made in elucidating the neurocircuits of pain, including those that mediate mechanical allodynia in the spinal cord (78–81). Nerve injury–induced allodynia in mice is mediated by direct cortical-spinal projections (82), and molecular and inflammatory mediators within these circuits represent important potential therapeutic targets for regenerative pain medicine (46).

Recent progress has demonstrated sex dimorphism in neuroinflammation regulation in pathological pain. For example, spinal microglia regulate inflammatory and neuropathic pain in male animals (83–85), whereas T cell signaling appears more critical in female animals (83). However, sex dimorphism in astrocytes in inflammatory and neuropathic pain is less evident (86).

Sex differences in peripheral immune regulation of pain have also been revealed. Adoptive transfer of paclitaxel-activated macrophages can elicit mechanical allodynia in both sexes. However, macrophage-derived TLR9 regulates chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in male mice (87). It is of great interest to investigate sex differences in macrophage signaling and the underlying mechanisms of sex-dependent macrophage-nociceptor interactions.

Importantly, these exciting advancements in our mechanistic understanding of pain may facilitate development of new therapeutic solutions. In Figures 2 and 3, we present where regenerative pain medicine, including blood-derived products (platelet-rich plasma and autologous conditioned serum) and cell-derived products (mesenchymal stromal cells and stem cells), can produce long-lasting pain relief via control of neuroinflammation in the pain-transmitting system.

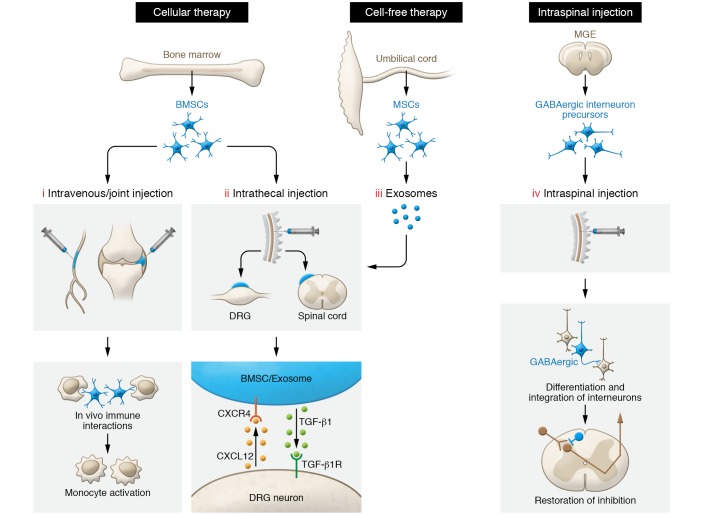

Figure 2. Preclinical models of cellular and cell-free exosome therapies for chronic pain.

(i) Single systemic or local injection of BMSCs can reverse mechanical allodynia by in vivo immune interactions and activation of monocytes. (ii) Intrathecally injected BMSCs migrate to meninges of injured DRG neurons and spinal cord dorsal horn via a CXCL12/CXCR4 homing mechanism. TGF-β1 secretion by BMSCs confers potent long-term pain relief by activation of the neuronal TGF-β receptor (TGF-βR). (iii) Intrathecal injection of exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal cells can serve as cell-free therapy for neuropathic pain. (iv) Transplantation of embryonic cortical GABAergic interneuron precursors from the medial ganglionic eminence (MGE) into the spinal cord leads to the development of inhibitory neurons. Furthermore, these GABAergic neurons integrate into spinal nociceptive circuits, mediating pain relief by release of GABA that acts on host-transplant inhibitory synaptic circuits.

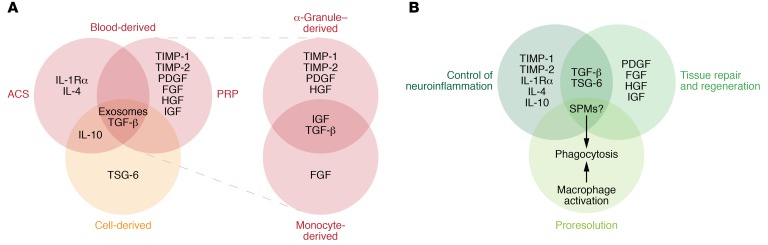

Figure 3. Clinically used blood-derived and cell-derived pain therapies and their mechanisms of action via production of therapeutic mediators.

(A) PRP contains (a) α-granule–derived growth factors such as PDGF, TGF-β, and HGF, as well as TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 and (b) monocyte-derived factors including TGF-β, FGF, and IGF. ACS provides factors including IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Rα), IL-4, IL-10, and TGF-β. MSCs have been found in clinical treatments to alter macrophage phenotypes, leading to direct and indirect production of IL-10 and TGF-β. MSCs also produce TSG-6 to inhibit inflammation and promote wound healing. Blood- and cell-derived therapies could also contain exosomes.(B) Common therapeutic mediators and mechanisms of action include (a) control of neuroinflammation, (b) tissue repair, and (c) pro-resolution processes. Notably, PRP, ACS, and MSCs may also contain or produce SPMs that produce multiple beneficial effects. ACS, autologous conditioned serum; MSC, mesenchymal stromal cells; PRP, platelet-rich plasma; SPM, specialized pro-resolving mediators.

Regenerative pain medicine

Regenerative medicine, defined as “the process of creating living, functional tissues to repair or replace tissue or organ function lost due to age, disease, damage, or congenital defects” (88), has garnered a great deal of enthusiasm over the past few years, not only because of its tissue-restoring potential, but also because of the emerging evidence of analgesic benefit in degenerative arthritis and neurologic conditions. Current regenerative pain therapies cover various treatments and technologies and may be split into two general categories: cellular products derived from bone marrow, lipid, umbilical cord, etc., and blood-derived products such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and autologous conditioned serum (ACS) (89–91). Stem and precursor cells are now available from a wide variety of sources (e.g., embryos, gestational and adult tissues, and reprogrammed differentiated cells).

Mesenchymal cells exist in the perivascular space of nearly all organs. These multipotent cells are capable of differentiating into other mesodermic tissues such as cartilage, fat, muscle, and bone with appropriate culturing techniques. These cells, sourced from a broad array of tissues such as bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord tissue, and peripheral blood, are the basis of what is broadly termed “mesenchymal stem cells” and what many now refer to as “mesenchymal stromal cells” or “medicinal signaling cells” (92). In this Review, we collectively refer to this heterogeneous cell population as “MSCs.” These cellular constituents are extracted from the source tissues and may or may not be cultured/expanded. As such, these processes create a divergent spectrum of cell lines with various cell surface markers and characteristics.

Preclinical studies of MSCs and neuronal precursor cells.

Bone marrow–derived MSCs (BMSCs) were first described in 1968 by Friedenstein et al. (93), and the culturing techniques used to form mesodermal phenotypes from these cells were later developed and described by Caplan (94). Preclinical studies have examined the efficacy of a variety of cellular therapies in different animal models of clinical neuropathic pain conditions. Special attention has been paid to BMSCs, as numerous early studies investigated the efficacy of BMSC treatment by intravenous (systemic) injection or localized injection directly into the site of injury (95). These studies demonstrated the analgesic effects of BMSC treatment in a wide range of rodent models of neuropathic pain after nerve injury, spinal cord injury, streptozotocin-induced diabetic neuropathy, and arthritic pain, using cells sourced from mouse, rat, and human bone marrow (95).

In 2011, Guo et al. showed that a single intravenous or local (lesion site) injection of rat BMSCs reversed mechanical allodynia in rats after tendon injury. The opioid receptor antagonist naloxone blocked this anti-allodynic effect, suggesting endogenous opioid involvement (96). The group’s follow-up study further demonstrated that in vivo immune interactions and monocyte activation underlie the long-lasting pain-relieving effects of these cells (97) (Figure 2). Sustained analgesia by BSMCs requires activation of central brain stem μ-opioid receptors and CXCL1/CXCR2 chemokine signaling (97).

Chen et al. demonstrated that intrathecal administration is also an effective way to deliver BMSCs for long-term pain relief (66). A single injection of 250,000 murine BMSCs via lumbar puncture provided rapid-acting, potent, and long-lasting pain relief for more than 6 weeks in mouse models of neuropathic pain (66). After intrathecal injection, dye-labeled BMSCs migrated to the DRG and spinal cord meninges, where they survived for up to 3 months (66) (Figure 2). Interestingly, after nerve ligation, the injured DRG neurons upregulated CXCL12, a chemotactic signal that guides BMSCs to the damaged DRGs via a CXCR4/CXCL12 homing mechanism. Importantly, TGF-β1 secretion by BMSCs was the specific factor conferring potent pain relief (66). Notably, intrathecal administration of anti–TGF-β1 neutralizing antibody selectively reversed the analgesic effect conferred by intrathecal BMSC treatment (66). Intrathecal BMSCs also effectively reduce nerve injury–induced neuroinflammation in the spinal cord, including microglia and astrocyte activation and increased expression of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF (66) (Figure 2).

The MSC treatment reversed microglia and astrocyte activation, suggesting that MSCs may regulate immune cells and neurons by paracrine activity of TGF and IL-10 (98, 99). With this further confirmation of the analgesic effects of intrathecally and intravenously administered BMSCs and adipose-derived MSCs in rat chronic constriction injury (CCI) nerve injury models (100), the preclinical studies of MSC populations and products demonstrate powerful potential in treating chronic neuropathic conditions. Hua et al. found new applications of stem cell therapy in the realm of pain medicine, particularly the therapy’s ability to also prevent and reverse opioid tolerance (OT) and opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) (98). MSC transplantation (intrathecal or intravenous) had significant therapeutic effects in both preventing the onset of OT and OIH when delivered prior to initiation of daily morphine injections, and reversing established OT and OIH in rats and mice.

It is noteworthy that exosomes derived from human umbilical cord MSCs also serve as a cell-free therapy for nerve injury–induced neuropathic pain in rats (101) (Figure 2). A single intrathecal injection of exosomes reversed mechanical and thermal hypersensitivities for 24 hours, and continuous infusion of exosomes into the intrathecal space prevented and reversed nerve ligation–induced pain for 2 weeks. The exosomes migrated specifically to the spinal dorsal horn, DRG, and peripheral axons associated with the ipsilateral nerve injury, and suppressed glial activation. Exosomes depressed TNF and IL-1β levels and reciprocally enhanced levels of IL-10, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor in DRGs with axonal injury (101). Future studies are warranted to compare the analgesic impact of MSC-derived exosomes versus MSCs per se.

Several antiinflammatory cytokines, including TGF-β, IL-10, IL-4, and TIMPs, are implicated in the analgesic actions of MSCs (Figures 2 and 3). MSCs mediate immunomodulatory actions via TGF-β (102, 103), and TGF-β is required for generating persistent analgesia following intrathecal administration of BMSCs (66). IL-10 release from BMSCs was relatively low, and IL-10 neutralization failed to reverse BMSC-induced inhibition of neuropathic pain in mice (66). However, a recent study showed that IL-1β–pretreated BMSCs enhanced analgesia of intrathecally injected BMSCs in rat neuropathic pain after spinal nerve ligation, and these analgesic effects were reversed by both TGF-β1 and IL-10 antibody neutralization (104). Recently, human umbilical cord plasma was found to be enriched with TIMP-2, an endogenous inhibitor of MMP-2 and neuroinflammation; this study revealed that systemic treatments with umbilical cord plasma and TIMP-2 increased synaptic plasticity and hippocampal-dependent cognition in aged mice (105). Intra-articular injection of MSCs produces TNF-stimulated gene 6 protein (TSG-6) that acts as an arthritis-associated hyaluronan binding protein, and displays antiinflammatory and cartilage-protective actions (106). BMSC-secreted TSG-6 also attenuates intervertebral disc degeneration by inhibiting the TLR signaling in rats (107).

In addition to MSCs, Braz et al. showed that embryonic cortical GABAergic interneuron precursors from the medial ganglionic eminence (MGE) could survive in mouse spinal cord after transplantation (108). MGE cell transplantation in the spinal cord either before or after nerve injury induced development of inhibitory neurons that integrated into nociceptive circuits, forming GABA-A–mediated inhibitory synapses in host mice, ultimately leading to either prevention or reduction of neuropathic pain (108, 109). Additional studies revealed that MGE cell transplantation mediates pain relief specifically via synaptic GABA release into the newly formed host-transplant inhibitory synaptic circuits (110) (Figure 2).

PRP in clinical applications.

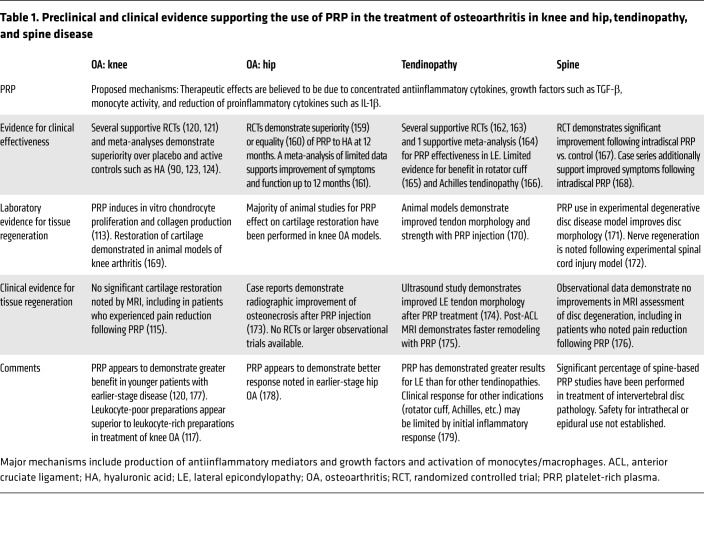

The use of PRP for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions and arthritis has grown substantially over the past couple of decades, secondary to its rich supply of α-granule–based growth factors (111) (Table 1). Platelet-derived growth factors include TGF-β, PDGF, and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF). TGF-β appears to promote chondrocyte activity and cartilage growth (65). PRP-based factors have been shown to reduce inflammatory cytokine activation (112), promote collagen and proteoglycan production in vitro (113), and enhance endogenous hyaluronic acid (HA) secretion in arthritis patients (114). However, PRP does not appear to contribute substantially to radiographic restoration of cartilage in humans (115).

Table 1. Preclinical and clinical evidence supporting the use of PRP in the treatment of osteoarthritis in knee and hip, tendinopathy, and spine disease.

PRP contains monocytes and neutrophils in varying concentrations, depending on the method of preparation. While proinflammatory neutrophil activity was shown to be detrimental to synoviocytes (116) and associated with worse outcomes in the treatment of osteoarthritis (117), monocytes, especially macrophages with antiinflammatory M2 phenotype, secrete growth factors including TGF-β, FGF, and IGF (118) that promote endogenous hematopoietic stem cell and progenitor cell recruitment to the delivery site (119). Other important anabolic constituents of PRP include TIMPs, with previously discussed important roles in attenuating the early- and late-phase development of neuropathic pain (51).

The majority of randomized clinical trials using PRP explored the treatment of knee osteoarthritis (120, 121) and support its functional benefits. Not all studies demonstrate PRP’s superiority over current treatments (e.g., HA) in osteoarthritis patients (122), although the method of platelet preparation in one of the negative trials was criticized for a potentially high leukocyte count and greater inflammatory signal (112). There are now multiple meta-analyses and systematic reviews of randomized clinical trials supporting the superiority of PRP versus HA at 6 months (123) and at 12 months or greater (90, 124).

ACS in clinical applications.

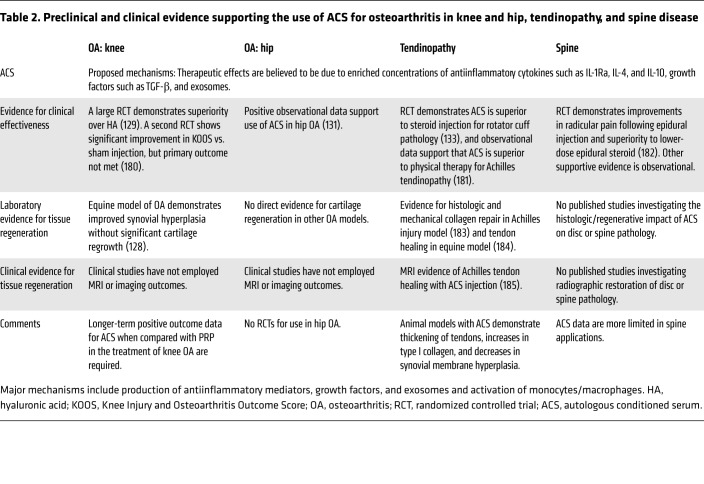

Another blood-derived regenerative product, ACS, was developed with the knowledge that augmented levels of IL-1Ra, a cartilage-protective cytokine, reduces both pain and joint damage in arthritis (91) (Table 2). Laboratory studies furthermore revealed that whole blood, given proper incubation conditions, produced not only substantial amounts of IL-1Ra, but also anabolic growth factors such as TGF-β, antiinflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10, and extracellular vesicles such as exosomes, collectively described as a whole blood clot secretome (91, 125, 126). The multifactorial analgesic mechanisms of ACS-induced analgesia are supported by the observation that intra-articular recombinant IL-1Ra alone does not produce clinically meaningful results in osteoarthritis patients (127). Processing techniques have been subsequently studied and standardized for clinical use, avoiding the variability seen in PRP production (91). In animal models, ACS treatment produces tendon thickening, greater concentrations of type I collagen, and decreases in synovial membrane hyperplasia (128).

Table 2. Preclinical and clinical evidence supporting the use of ACS for osteoarthritis in knee and hip, tendinopathy, and spine disease.

A randomized, blinded trial with 376 participants revealed superior outcomes of ACS over intra-articular HA or placebo. The ACS group’s improvements were maintained for at least 2 years (129). The longer-term impact of ACS is also supported by a 2-year observational trial in 118 patients in combination with physical therapy (130). Patients noted 62% and 56% decreases in Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and WOMAC pain scale scores, respectively. Positive observational results also support the use of ACS for hip arthritis (131). A randomized trial of ACS injection in patients who had undergone anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction additionally demonstrated superior pain scale scores and reduced bone-tunnel widening in the treatment group at all time points (132). ACS furthermore demonstrates superiority to steroid injection for the treatment of rotator cuff tendon pathology (133).

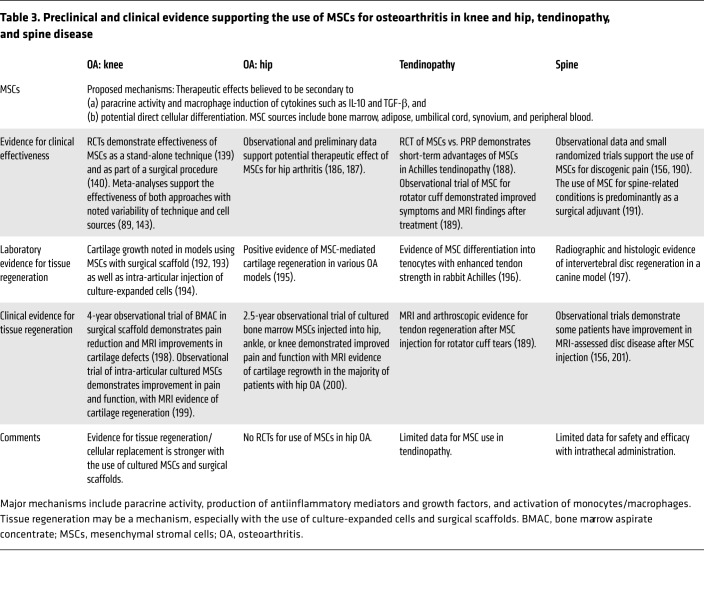

MSCs in clinical applications.

Extensive preclinical work demonstrated the potential therapeutic effects of MSCs through expanded and cultured cell lines (95). MSC treatment is known to suppress the release of inflammatory factors from chondrocytes and improve radiographic and histologic markers of osteoarthritis in experimental arthritis models (134, 135). It appears that cartilage regeneration is further facilitated when differentiated chondrocytes are used (136). Systemically infused MSCs have a short life expectancy, but induce a phenotypic change in macrophages with subsequent production of anabolic and antiinflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β (137).

MSC therapies defy standard classification systems to an even greater extent than PRP does, given not only the multiple methodologies for preparation, but diverse cellular sources (Table 3). MSCs additionally go through several types of mechanical or biochemical extraction, and may be injected immediately or cultured for days to weeks prior to injection. At the time of administration, they have variable phenotypes with cell surface markers consistent with mesenchymal cells, hematologic cells, or a hybrid. In human clinical studies, important distinctions should be made between products that are cultured and expanded, demonstrating mesenchymal cell surface molecules such as CD73, CD90, or CD105, and products that are processed and injected in the same surgical/procedural setting. This multitude of processes for isolating and culturing MSCs prompted the International Society for Cellular Therapy to establish and identify criteria for MSCs (138). However, these criteria are rarely used in current publications.

Table 3. Preclinical and clinical evidence supporting the use of MSCs for osteoarthritis in knee and hip, tendinopathy, and spine disease.

A growing number of trials demonstrate favorable results for the use of MSCs in the treatment of osteoarthritis, including studies using cells derived from bone marrow (139, 140), adipose tissue (141), and peripheral blood (142) (Table 3). The positive therapeutic impact of MSCs for the treatment of arthritis is supported by both recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses (89, 143), although concerns about bias have been expressed (144).

Enthusiasm about the possibility of cartilage regrowth with MSC therapies was further inspired by demonstration that MSCs alleviated cartilage defects to a greater extent when added to surgical interventions such as microfracturing (145) or as an isolated nonsurgical procedure (146). As a result, MSC therapies are now commonly employed as a stand-alone procedure (143), or in conjunction with surgical repair, using bioengineered scaffolds to support cellular growth (140). A divergence between clinical effect and cartilage regrowth was observed in studies demonstrating improved function and pain despite persistent cartilage defects (147), implying that the analgesic benefits may result from nonregenerative mechanisms.

Concluding remarks and future directions

Neuroinflammation is associated with various chronic pain conditions and contributes to central and peripheral sensitization (46). Genetic and psychological factors such as chronic stress and comorbidities such as depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline are also associated with neuroinflammatory upregulation and chronic pain (46, 148). Furthermore, treatments for chronic pain, such as opioid usage, may paradoxically worsen neuroinflammation, leading to opioid-induced tolerance, hyperalgesia, and subsequent dose escalation, highlighted in the ongoing opioid crisis (149, 150). Peripheral drivers of osteoarthritis pain, including inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF (151), are especially important in early disease (152). Conversely, diminished production of antiinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1Ra (62) and TGF-β (65) plays an important role in the progression of degenerative joint disease.

Based on the growing biochemical understanding of pain in osteoarthritis, the use of biologically based regenerative pain therapies has grown dramatically over the past decade. Common treatments include autologous blood products such as PRP and ACS, and cellular therapies such as MSCs. It has historically been believed that tissue regeneration with MSC-based interventions is critical to the pain and functional improvements seen after treatment; however, recent studies highlight that the analgesic effects of these therapies may be largely independent of cellular replacement (Figure 3) and more related to paracrine effects and immune modulation (153–155). Supporting this concept, Pettine et al. actually noted that positive clinical outcomes of MSC treatment for degenerative disc disease correlated with the concentration of CD34 cell surface markers (a marker for hematologic cells, not mesenchymal cells) detected on injected MSCs (156). Furthermore, it has been noted that the majority of BMSCs are trapped in the lung immediately after intravenous infusion (157) and their survival time in the host is inconsistent with their duration of pain relief (several months) (97). It has been hypothesized that the cartilage regeneration noted in some MSC-based clinical trials may be due to the cellular components acting as an anabolic substrate for endogenous cartilage growth; analgesia across the spectrum of regenerative therapies may be secondary to common immune mechanisms.

There remain several outstanding questions for future studies. First, it is increasingly clear that regenerative therapies need ongoing mechanistic studies and rigorous clinical trials to better define the optimal indications, safety, sources, and processing for this wealth of products. Second, SPMs play critical roles in the resolution of inflammation and pathological pain (75, 77), and human peritoneal stem cells release SPMs during antimicrobial activities (158). It remains unknown whether SPMs are also among the therapeutic mediators produced by PRP, ACS, and MSCs (Figure 3). Third, sex dimorphism has been revealed in immune regulation of pain in animals (83, 86, 87). It is of great interest to investigate whether pain relief by BMSCs is sex-specific. Last but not least, clinical guidelines based on preclinical scientific research and clinical evidence must be established to provide a framework for decision-making in the application of these blood and cellular products. The potential to ameliorate symptoms and modulate disease processes with regenerative therapies exists but will require a conscientious and scientifically driven approach to be fulfilled.

In summary, regenerative therapies play a growing role in the treatment of degenerative musculoskeletal and neurologic conditions with widespread use across the world. The effectiveness of these treatments is supported by a growing body of evidence that demonstrates improvements in function and pain after treatment, and some evidence for tissue regeneration. The observed divergence between the positive clinical outcomes and evidence for tissue regeneration further highlights the importance of immune modulation and neuro-immune interactions across the spectrum of regenerative therapies (Figure 3). Thus, this Review creates a conceptual and mechanistic framework to evaluate future research of regenerative medicine.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by the Duke University Anesthesiology Research Fund, a Department of Defense grant (10669042 to JC), and the Lisa Dean Moseley Foundation (LDMF1709JC to JC).

Version 1. 04/06/2020

Electronic publication

Version 2. 05/01/2020

Print issue publication

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: RRJ is a consultant for Boston Scientific and received research support from the company. He serves on the board of directors of Ascletis Pharma. He filed a patent, “Methods for treating pain” (WO2017011352A1), from Duke University. TB is a consultant for Mainstay Medical, Summus, and Best Doctors. WM is a consultant for and on the supervisory board of Orthogen AG, a company that focuses on regenerative medicine.

Copyright: © 2020, American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Reference information: J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2164–2176.https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI134439.

Contributor Information

Thomas Buchheit, Email: thomas.buchheit@duke.edu.

Yul Huh, Email: yul.huh@duke.edu.

William Maixner, Email: william.maixner@duke.edu.

Jianguo Cheng, Email: CHENGJ@ccf.org.

Ru-Rong Ji, Email: ru-rong.ji@duke.edu.

References

- 1.Pizzo PA, Clark NM. Alleviating suffering 101—pain relief in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(3):197–199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gereau RW, et al. A pain research agenda for the 21st century. J Pain. 2014;15(12):1203–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arthritis Foundation. What is Arthritis? https://www.arthritis.org/about-arthritis/understanding-arthritis/what-is-arthritis.php Accessed February 27, 2020.

- 4.McAlindon TE, et al. Effect of intra-articular triamcinolone vs saline on knee cartilage volume and pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(19):1967–1975. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.5283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jevsevar D, Donnelly P, Brown GA, Cummins DS. Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review of the evidence. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(24):2047–2060. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624–1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woolf CJ, Ma Q. Nociceptors—noxious stimulus detectors. Neuron. 2007;55(3):353–364. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gold MS, Gebhart GF. Nociceptor sensitization in pain pathogenesis. Nat Med. 2010;16(11):1248–1257. doi: 10.1038/nm.2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Julius D, Basbaum AI. Molecular mechanisms of nociception. Nature. 2001;413(6852):203–210. doi: 10.1038/35093019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hucho T, Levine JD. Signaling pathways in sensitization: toward a nociceptor cell biology. Neuron. 2007;55(3):365–376. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iyer SM, et al. Virally mediated optogenetic excitation and inhibition of pain in freely moving nontransgenic mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(3):274–278. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiu IM, et al. Transcriptional profiling at whole population and single cell levels reveals somatosensory neuron molecular diversity. Elife. 2014;3:e04660. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Usoskin D, et al. Unbiased classification of sensory neuron types by large-scale single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(1):145–153. doi: 10.1038/nn.3881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li CL, et al. Somatosensory neuron types identified by high-coverage single-cell RNA-sequencing and functional heterogeneity. Cell Res. 2016;26(8):967. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng Y, Liu P, Bai L, Trimmer JS, Bean BP, Ginty DD. Deep Sequencing of Somatosensory Neurons Reveals Molecular Determinants of Intrinsic Physiological Properties. Neuron. 2019;103(4):598–616.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wainger BJ, et al. Modeling pain in vitro using nociceptor neurons reprogrammed from fibroblasts. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(1):17–24. doi: 10.1038/nn.3886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davidson S, Copits BA, Zhang J, Page G, Ghetti A, Gereau RW. Human sensory neurons: membrane properties and sensitization by inflammatory mediators. Pain. 2014;155(9):1861–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Hartung JE, Friedman RL, Koerber HR, Belfer I, Gold MS. Nicotine evoked currents in human primary sensory neurons. J Pain. 2019;20(7):810–818. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang W, Berta T, Kim YH, Lee S, Lee SY, Ji RR. Expression and role of voltage-gated sodium channels in human dorsal root ganglion neurons with special focus on Nav1.7, species differences, and regulation by paclitaxel. Neurosci Bull. 2018;34(1):4–12. doi: 10.1007/s12264-017-0132-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waxman SG. Painful Na-channelopathies: an expanding universe. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19(7):406–409. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett DL, Woods CG. Painful and painless channelopathies. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(6):587–599. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, et al. DRG voltage-gated sodium channel 1.7 is upregulated in paclitaxel-induced neuropathy in rats and in humans with neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2018;38(5):1124–1136. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0899-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costigan M, Scholz J, Woolf CJ. Neuropathic pain: a maladaptive response of the nervous system to damage. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu ZZ, et al. Inhibition of mechanical allodynia in neuropathic pain by TLR5-mediated A-fiber blockade. Nat Med. 2015;21(11):1326–1331. doi: 10.1038/nm.3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan H, et al. Identification of a Spinal Circuit for Mechanical and Persistent Spontaneous Itch. Neuron. 2019;103(6):1135–1149.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Binshtok AM, Bean BP, Woolf CJ. Inhibition of nociceptors by TRPV1-mediated entry of impermeant sodium channel blockers. Nature. 2007;449(7162):607–610. doi: 10.1038/nature06191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orefice LL, et al. Targeting peripheral somatosensory neurons to improve tactile-related phenotypes in ASD models. Cell. 2019;178(4):867–886.e24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han Q, et al. SHANK3 Deficiency Impairs Heat Hyperalgesia and TRPV1 Signaling in Primary Sensory Neurons. Neuron. 2016;92(6):1279–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Topalian SL, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen G, et al. PD-L1 inhibits acute and chronic pain by suppressing nociceptive neuron activity via PD-1. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20(7):917–926. doi: 10.1038/nn.4571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mo K, et al. MBD1 contributes to the genesis of acute pain and neuropathic pain by epigenetic silencing of Oprm1 and Kcna2 genes in primary sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2018;38(46):9883–9899. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0880-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao X, et al. A long noncoding RNA contributes to neuropathic pain by silencing Kcna2 in primary afferent neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(8):1024–1031. doi: 10.1038/nn.3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laumet G, et al. G9a is essential for epigenetic silencing of K(+) channel genes in acute-to-chronic pain transition. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(12):1746–1755. doi: 10.1038/nn.4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peng C, et al. miR-183 cluster scales mechanical pain sensitivity by regulating basal and neuropathic pain genes. Science. 2017;356(6343):1168–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma J, et al. Cell-specific role of histone deacetylase 6 in chemotherapy-induced mechanical allodynia and loss of intraepidermal nerve fibers. Pain. 2019;160(12):2877–2890. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ji RR, Chamessian A, Zhang YQ. Pain regulation by non-neuronal cells and inflammation. Science. 2016;354(6312):572–577. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ji RR, Donnelly CR, Nedergaard M. Astrocytes in chronic pain itch. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2019;20(11):667–685. doi: 10.1038/s41583-019-0218-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baral P, Udit S, Chiu IM. Pain and immunity: implications for host defence. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19(7):433–447. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0147-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ren K, Dubner R. Interactions between the immune and nervous systems in pain. Nat Med. 2010;16(11):1267–1276. doi: 10.1038/nm.2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McMahon SB, La Russa F, Bennett DL. Crosstalk between the nociceptive and immune systems in host defence and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(7):389–402. doi: 10.1038/nrn3946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griffin RS, et al. Complement induction in spinal cord microglia results in anaphylatoxin C5a-mediated pain hypersensitivity. J Neurosci. 2007;27(32):8699–8708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2018-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cobos EJ, et al. Mechanistic differences in neuropathic pain modalities revealed by correlating behavior with global expression profiling. Cell Rep. 2018;22(5):1301–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ji RR, Xu ZZ, Gao YJ. Emerging targets in neuroinflammation-driven chronic pain. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(7):533–548. doi: 10.1038/nrd4334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ellis A, Bennett DL. Neuroinflammation and the generation of neuropathic pain. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(1):26–37. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Costigan M, et al. T-cell infiltration and signaling in the adult dorsal spinal cord is a major contributor to neuropathic pain-like hypersensitivity. J Neurosci. 2009;29(46):14415–14422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4569-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ji RR, Nackley A, Huh Y, Terrando N, Maixner W. Neuroinflammation and central sensitization in chronic and widespread pain. Anesthesiology. 2018;129(2):343–366. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Latremoliere A, Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: a generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J Pain. 2009;10(9):895–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu Y, et al. A feed-forward spinal cord glycinergic neural circuit gates mechanical allodynia. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(9):4050–4062. doi: 10.1172/JCI70026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vandooren J, Van Damme J, Opdenakker G. On the structure and functions of gelatinase B/matrix metalloproteinase-9 in neuroinflammation. Prog Brain Res. 2014;214:193–206. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63486-3.00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ji RR, Xu ZZ, Wang X, Lo EH. Matrix metalloprotease regulation of neuropathic pain. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30(7):336–340. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawasaki Y, et al. Distinct roles of matrix metalloproteases in the early- and late-phase development of neuropathic pain. Nat Med. 2008;14(3):331–336. doi: 10.1038/nm1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jin SX, Zhuang ZY, Woolf CJ, Ji RR. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is activated after a spinal nerve ligation in spinal cord microglia and dorsal root ganglion neurons and contributes to the generation of neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2003;23(10):4017–4022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04017.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsuda M, Mizokoshi A, Shigemoto-Mogami Y, Koizumi S, Inoue K. Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in spinal hyperactive microglia contributes to pain hypersensitivity following peripheral nerve injury. Glia. 2004;45(1):89–95. doi: 10.1002/glia.10308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adams SB, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases in the synovial fluid after intra-articular ankle fracture. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36(11):1264–1271. doi: 10.1177/1071100715611176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhuang ZY, Gerner P, Woolf CJ, Ji RR. ERK is sequentially activated in neurons, microglia, and astrocytes by spinal nerve ligation and contributes to mechanical allodynia in this neuropathic pain model. Pain. 2005;114(1-2):149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Knight BE, et al. TIMP-1 attenuates the development of inflammatory pain through MMP-dependent and receptor-mediated cell signaling mechanisms. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12:220. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parisien M, et al. Genetic pathway analysis reveals a major role for extracellular matrix organization in inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Pain. 2019;160(4):932–944. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Binshtok AM, et al. Nociceptors are interleukin-1beta sensors. J Neurosci. 2008;28(52):14062–14073. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3795-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kawasaki Y, Zhang L, Cheng JK, Ji RR. Cytokine mechanisms of central sensitization: distinct and overlapping role of interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in regulating synaptic and neuronal activity in the superficial spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2008;28(20):5189–5194. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3338-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yan X, Jiang E, Gao M, Weng HR. Endogenous activation of presynaptic NMDA receptors enhances glutamate release from the primary afferents in the spinal dorsal horn in a rat model of neuropathic pain. J Physiol (Lond) 2013;591(7):2001–2019. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.250522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan X, Jiang E, Weng HR. Activation of toll like receptor 4 attenuates GABA synthesis and postsynaptic GABA receptor activities in the spinal dorsal horn via releasing interleukin-1 beta. J Neuroinflammation. 2015;12:222. doi: 10.1186/s12974-014-0222-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arend WP, Malyak M, Guthridge CJ, Gabay C. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist: role in biology. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:27–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grace PM, et al. Morphine paradoxically prolongs neuropathic pain in rats by amplifying spinal NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(24):E3441–E3450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602070113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lantero A, Tramullas M, Díaz A, Hurlé MA. Transforming growth factor-β in normal nociceptive processing and pathological pain models. Mol Neurobiol. 2012;45(1):76–86. doi: 10.1007/s12035-011-8221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pujol JP, et al. Interleukin-1 and transforming growth factor-beta 1 as crucial factors in osteoarthritic cartilage metabolism. Connect Tissue Res. 2008;49(3):293–297. doi: 10.1080/03008200802148355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen G, Park CK, Xie RG, Ji RR. Intrathecal bone marrow stromal cells inhibit neuropathic pain via TGF-β secretion. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(8):3226–3240. doi: 10.1172/JCI80883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Echeverry S, Shi XQ, Haw A, Liu H, Zhang ZW, Zhang J. Transforming growth factor-beta1 impairs neuropathic pain through pleiotropic effects. Mol Pain. 2009;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tramullas M, et al. MicroRNA-30c-5p modulates neuropathic pain in rodents. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(453):eaao6299. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao6299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McKelvey R, Berta T, Old E, Ji RR, Fitzgerald M. Neuropathic pain is constitutively suppressed in early life by anti-inflammatory neuroimmune regulation. J Neurosci. 2015;35(2):457–466. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2315-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sloane EM, Soderquist RG, Maier SF, Mahoney MJ, Watkins LR, Milligan ED. Long-term control of neuropathic pain in a non-viral gene therapy paradigm. Gene Ther. 2009;16(4):470–475. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grace PM, et al. Prior voluntary wheel running attenuates neuropathic pain. Pain. 2016;157(9):2012–2023. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.da Silva MD, Bobinski F, Sato KL, Kolker SJ, Sluka KA, Santos AR. IL-10 cytokine released from M2 macrophages is crucial for analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of acupuncture in a model of inflammatory muscle pain. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;51(1):19–31. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8790-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Krukowski K, et al. CD8+ T Cells and Endogenous IL-10 Are Required for Resolution of Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathic Pain. J Neurosci. 2016;36(43):11074–11083. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3708-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bobinski F, Teixeira JM, Sluka KA, Santos ARS. Interleukin-4 mediates the analgesia produced by low-intensity exercise in mice with neuropathic pain. Pain. 2018;159(3):437–450. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Serhan CN. Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature. 2014;510(7503):92–101. doi: 10.1038/nature13479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang L, et al. Distinct analgesic actions of DHA and DHA-derived specialized pro-resolving mediators on post-operative pain after bone fracture in mice. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:412. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xu ZZ, et al. Resolvins RvE1 and RvD1 attenuate inflammatory pain via central and peripheral actions. Nat Med. 2010;16(5):592–597. doi: 10.1038/nm.2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peirs C, Seal RP. Neural circuits for pain: recent advances and current views. Science. 2016;354(6312):578–584. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Duan B, Cheng L, Ma Q. Spinal circuits transmitting mechanical pain and itch. Neurosci Bull. 2018;34(1):186–193. doi: 10.1007/s12264-017-0136-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Duan B, et al. Identification of spinal circuits transmitting and gating mechanical pain. Cell. 2014;159(6):1417–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Braz J, Solorzano C, Wang X, Basbaum AI. Transmitting pain and itch messages: a contemporary view of the spinal cord circuits that generate gate control. Neuron. 2014;82(3):522–536. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu Y, et al. Touch and tactile neuropathic pain sensitivity are set by corticospinal projections. Nature. 2018;561(7724):547–550. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0515-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sorge RE, et al. Different immune cells mediate mechanical pain hypersensitivity in male and female mice. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(8):1081–1083. doi: 10.1038/nn.4053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Taves S, et al. Spinal inhibition of p38 MAP kinase reduces inflammatory and neuropathic pain in male but not female mice: ex-dependent microglial signaling in the spinal cord. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;55:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sorge RE, et al. Spinal cord Toll-like receptor 4 mediates inflammatory and neuropathic hypersensitivity in male but not female mice. J Neurosci. 2011;31(43):15450–15454. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3859-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen G, Luo X, Qadri MY, Berta T, Ji RR. Sex-dependent glial signaling in pathological pain: distinct roles of spinal microglia and astrocytes. Neurosci Bull. 2018;34(1):98–108. doi: 10.1007/s12264-017-0145-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Luo X, et al. Macrophage Toll-like receptor 9 contributes to chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain in male mice. J Neurosci. 2019;39(35):6848–6864. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3257-18.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. [No authors listed]. Regenerative Medicine. National Institutes of Health. https://archives.nih.gov/asites/report/09-09-2019/report.nih.gov/nihfactsheets/ViewFactSheetc0d0.html?csid=62&key=R#R Updated June 30, 2018. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- 89.Goldberg A, Mitchell K, Soans J, Kim L, Zaidi R. The use of mesenchymal stem cells for cartilage repair and regeneration: a systematic review. J Orthop Surg Res. 2017;12(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s13018-017-0534-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Meheux CJ, McCulloch PC, Lintner DM, Varner KE, Harris JD. Efficacy of intra-articular platelet-rich plasma injections in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(3):495–505. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Evans CH, Chevalier X, Wehling P. Autologous conditioned serum. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2016;27(4):893–908. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells: time to change the name! Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6(6):1445–1451. doi: 10.1002/sctm.17-0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Friedenstein AJ, Petrakova KV, Kurolesova AI, Frolova GP. Heterotopic of bone marrow. Analysis of precursor cells for osteogenic and hematopoietic tissues. Transplantation. 1968;6(2):230–247. doi: 10.1097/00007890-196803000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ding DC, Shyu WC, Lin SZ. Mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Transplant. 2011;20(1):5–14. doi: 10.3727/096368910X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Huh Y, Ji RR, Chen G. Neuroinflammation, bone marrow stem cells, and chronic pain. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1014. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Guo W, et al. Bone marrow stromal cells produce long-term pain relief in rat models of persistent pain. Stem Cells. 2011;29(8):1294–1303. doi: 10.1002/stem.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Guo W, et al. In vivo immune interactions of multipotent stromal cells underlie their long-lasting pain-relieving effect. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):10107. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10251-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hua Z, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells reversed morphine tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32096. doi: 10.1038/srep32096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Li F, Liu L, Cheng K, Chen Z, Cheng J. The use of stem cell therapy to reverse opioid tolerance. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;103(6):971–974. doi: 10.1002/cpt.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu L, et al. Comparative efficacy of multiple variables of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation for the treatment of neuropathic pain in rats. Mil Med. 2017;182(S1):175–184. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shiue SJ, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes as a cell-free therapy for nerve injury-induced pain in rats. Pain. 2019;160(1):210–223. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhao ZG, Li WM, Chen ZC, You Y, Zou P. Immunosuppressive properties of mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Immunol Invest. 2008;37(7):726–739. doi: 10.1080/08820130802349940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nemeth K, et al. Bone marrow stromal cells use TGF-beta to suppress allergic responses in a mouse model of ragweed-induced asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(12):5652–5657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910720107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Li J, et al. Interleukin-1β pre-treated bone marrow stromal cells alleviate neuropathic pain through CCL7-mediated inhibition of microglial activation in the spinal cord. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42260. doi: 10.1038/srep42260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Castellano JM, et al. Human umbilical cord plasma proteins revitalize hippocampal function in aged mice. Nature. 2017;544(7651):488–492. doi: 10.1038/nature22067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ichiseki T, et al. Intraarticularly-injected mesenchymal stem cells stimulate anti-inflammatory molecules and inhibit pain related protein and chondrolytic enzymes in a monoiodoacetate-induced rat arthritis model. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(1):E203. doi: 10.3390/ijms19010203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yang H, et al. TSG-6 secreted by bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells attenuates intervertebral disc degeneration by inhibiting the TLR2/NF-κB signaling pathway. Lab Invest. 2018;98(6):755–772. doi: 10.1038/s41374-018-0036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bráz JM, et al. Forebrain GABAergic neuron precursors integrate into adult spinal cord and reduce injury-induced neuropathic pain. Neuron. 2012;74(4):663–675. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Etlin A, et al. Functional synaptic integration of forebrain GABAergic precursors into the adult spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2016;36(46):11634–11645. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2301-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Basbaum AI, Bráz JM. Long-term, dynamic synaptic reorganization after GABAergic precursor cell transplantation into adult mouse spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 2018;526(3):480–495. doi: 10.1002/cne.24346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Xie X, Zhang C, Tuan RS. Biology of platelet-rich plasma and its clinical application in cartilage repair. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(1):204. doi: 10.1186/ar4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.van Buul GM, et al. Platelet-rich plasma releasate inhibits inflammatory processes in osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(11):2362–2370. doi: 10.1177/0363546511419278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Akeda K, et al. Platelet-rich plasma stimulates porcine articular chondrocyte proliferation and matrix biosynthesis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2006;14(12):1272–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Anitua E, et al. Platelet-released growth factors enhance the secretion of hyaluronic acid and induce hepatocyte growth factor production by synovial fibroblasts from arthritic patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(12):1769–1772. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hart R, Safi A, Komzák M, Jajtner P, Puskeiler M, Hartová P. Platelet-rich plasma in patients with tibiofemoral cartilage degeneration. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2013;133(9):1295–1301. doi: 10.1007/s00402-013-1782-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Braun HJ, Kim HJ, Chu CR, Dragoo JL. The effect of platelet-rich plasma formulations and blood products on human synoviocytes: implications for intra-articular injury and therapy. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1204–1210. doi: 10.1177/0363546514525593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Riboh JC, Saltzman BM, Yanke AB, Fortier L, Cole BJ. Effect of leukocyte concentration on the efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(3):792–800. doi: 10.1177/0363546515580787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hickey DG, Frenkel SR, Di Cesare PE. Clinical applications of growth factors for articular cartilage repair. Am J Orthop. 2003;32(2):70–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Crane JL, Cao X. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and TGF-β signaling in bone remodeling. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(2):466–472. doi: 10.1172/JCI70050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Patel S, Dhillon MS, Aggarwal S, Marwaha N, Jain A. Treatment with platelet-rich plasma is more effective than placebo for knee osteoarthritis: a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(2):356–364. doi: 10.1177/0363546512471299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Vaquerizo V, et al. Comparison of intra-articular injections of plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF-Endoret) versus Durolane hyaluronic acid in the treatment of patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(10):1635–1643. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.07.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Di Martino A, et al. Platelet-rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid injections for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: results at 5 years of a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(2):347–354. doi: 10.1177/0363546518814532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Laudy AB, Bakker EW, Rekers M, Moen MH. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma injections in osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(10):657–672. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Dai WL, Zhou AG, Zhang H, Zhang J. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy. 2017;33(3):659–670.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Meijer H, Reinecke J, Becker C, Tholen G, Wehling P. The production of anti-inflammatory cytokines in whole blood by physico-chemical induction. Inflamm Res. 2003;52(10):404–407. doi: 10.1007/s00011-003-1197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. doi: 10.1089/rej.2019.2263. Shirokova L, Noskov S, Gorokhova V, Reinecke J, Shirokova K. Intra-articular injections of a whole blood clot secretome, autologous conditioned serum, have superior clinical and biochemical efficacy over platelet-rich plasma and induce rejuvenation-associated changes of joint metabolism: a prospective, controlled open-label clinical study in chronic knee osteoarthritis [published online February 10, 2020]. Rejuvenation Res . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 127.Chevalier X, et al. Intraarticular injection of anakinra in osteoarthritis of the knee: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(3):344–352. doi: 10.1002/art.24096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Frisbie DD, Kawcak CE, Werpy NM, Park RD, McIlwraith CW. Clinical, biochemical, and histologic effects of intra-articular administration of autologous conditioned serum in horses with experimentally induced osteoarthritis. Am J Vet Res. 2007;68(3):290–296. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.68.3.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Baltzer AW, Moser C, Jansen SA, Krauspe R. Autologous conditioned serum (Orthokine) is an effective treatment for knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2009;17(2):152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Baselga García-Escudero J, Miguel Hernández Trillos P. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee with a combination of autologous conditioned serum and physiotherapy: a two-year observational study. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0145551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Baltzer AW, Ostapczuk MS, Stosch D, Seidel F, Granrath M. A new treatment for hip osteoarthritis: clinical evidence for the efficacy of autologous conditioned serum. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2013;5(2):59–64. doi: 10.4081/or.2013.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Darabos N, Haspl M, Moser C, Darabos A, Bartolek D, Groenemeyer D. Intraarticular application of autologous conditioned serum (ACS) reduces bone tunnel widening after ACL reconstructive surgery in a randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(suppl 1):S36–S46. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Damjanov N, Barac B, Colic J, Stevanovic V, Zekovic A, Tulic G. The efficacy and safety of autologous conditioned serum (ACS) injections compared with betamethasone and placebo injections in the treatment of chronic shoulder joint pain due to supraspinatus tendinopathy: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Med Ultrason. 2018;20(3):335–341. doi: 10.11152/mu-1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Toghraie FS, et al. Treatment of osteoarthritis with infrapatellar fat pad derived mesenchymal stem cells in Rabbit. Knee. 2011;18(2):71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Jin R, Shen M, Yu L, Wang X, Lin X. Adipose-derived stem cells suppress inflammation induced by IL-1β through down-regulation of P2X7R mediated by miR-373 in chondrocytes of osteoarthritis. Mol Cells. 2017;40(3):222–229. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2017.2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Latief N, Raza FA, Bhatti FU, Tarar MN, Khan SN, Riazuddin S. Adipose stem cells differentiated chondrocytes regenerate damaged cartilage in rat model of osteoarthritis. Cell Biol Int. 2016;40(5):579–588. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.de Witte SFH, et al. Immunomodulation by therapeutic mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) is triggered through phagocytosis of MSC by monocytic cells. Stem Cells. 2018;36(4):602–615. doi: 10.1002/stem.2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Dominici M, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Vega A, et al. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis with allogeneic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: a randomized controlled trial. Transplantation. 2015;99(8):1681–1690. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Huh SW, et al. Autologous bone marrow mesenchymal cell induced chondrogenesis for the treatment of osteoarthritis of knee. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2016;13(2):200–209. doi: 10.1007/s13770-016-9125-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Russo A, Condello V, Madonna V, Guerriero M, Zorzi C. Autologous and micro-fragmented adipose tissue for the treatment of diffuse degenerative knee osteoarthritis. J Exp Orthop. 2017;4(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s40634-017-0108-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Saw KY, et al. Articular cartilage regeneration with autologous peripheral blood stem cells versus hyaluronic acid: a randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(4):684–694. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Yubo M, Yanyan L, Li L, Tao S, Bo L, Lin C. Clinical efficacy and safety of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation for osteoarthritis treatment: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Pas HI, Winters M, Haisma HJ, Koenis MJ, Tol JL, Moen MH. Stem cell injections in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review of the literature. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(15):1125–1133. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Wakitani S, Imoto K, Yamamoto T, Saito M, Murata N, Yoneda M. Human autologous culture expanded bone marrow mesenchymal cell transplantation for repair of cartilage defects in osteoarthritic knees. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2002;10(3):199–206. doi: 10.1053/joca.2001.0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Orozco L, et al. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis with autologous mesenchymal stem cells: a pilot study. Transplantation. 2013;95(12):1535–1541. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318291a2da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Koh YG, Choi YJ, Kwon OR, Kim YS. Second-look arthroscopic evaluation of cartilage lesions after mesenchymal stem cell implantation in osteoarthritic knees. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(7):1628–1637. doi: 10.1177/0363546514529641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Maixner W, Fillingim RB, Williams DA, Smith SB, Slade GD. Overlapping chronic pain conditions: implications for diagnosis and classification. J Pain. 2016;17(9 suppl):T93–T107. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Watkins LR, Hutchinson MR, Rice KC, Maier SF. The “toll” of opioid-induced glial activation: improving the clinical efficacy of opioids by targeting glia. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30(11):581–591. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.DeLeo JA, Tanga FY, Tawfik VL. Neuroimmune activation and neuroinflammation in chronic pain and opioid tolerance/hyperalgesia. Neuroscientist. 2004;10(1):40–52. doi: 10.1177/1073858403259950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]