Abstract

Since a thorough review in 2011 by Spruyt, into the integral pitfalls of pediatric questionnaires in sleep, sleep researchers worldwide have further evaluated many existing tools. This systematic review aims to comprehensively evaluate and summarize the tools currently in circulation and provide recommendations for potential evolving avenues of pediatric sleep interest. 144 “tool”-studies (70 tools) have been published aiming at investigating sleep in primarily 6–18 years old per parental report. Although 27 new tools were discovered, most of the studies translated or evaluated the psychometric properties of existing tools. Some form of normative values has been established in 18 studies. More than half of the tools queried general sleep problems. Extra efforts in tool development are still needed for tools that assess children outside the 6-to-12-year-old age range, as well as for tools examining sleep-related aspects beyond sleep problems/disorders. Especially assessing the validity of tools has been pursued vis-à-vis fulfillment of psychometric criteria. While the Spruyt et al. review provided a rigorous step-by-step guide into the development and validation of such tools, a pattern of steps continue to be overlooked. As these instruments are potentially valuable in assisting in the development of a clinical diagnosis into pediatric sleep pathologies, it is required that while they are primary subjective measures, they behave as objective measures. More tools for specific populations (e.g., in terms of ages, developmental disabilities, and sleep pathologies) are still needed.

Keywords: sleep duration, sleep quality, sleep hygiene, questionnaire, child, review

Introduction

There is significant power in the efficiency and cost-effective nature of questionnaires and surveys as contributors to aetiological discoveries of a wide range of medical disorders. These instruments however, do not always possess the objective nature of medically advised and established tools, e.g., polysomnography, and can become a hindrance to adequate diagnoses, particularly when neglecting recommendations of their development (1). Despite these problems, there has been considerable effort to transform the structure of health questionnaires, specifically in the field of pediatric sleep, to reflect a systematic approach of the highest concordance to medical diagnostic standards. The systematic review by Spruyt et al. (2, 3) in 2011, publicly summarized the shortcomings of questionnaires and their developmental standards while advising a thorough procedure in which to follow to adequately evaluate or develop a tool.

Since this time, a variety of tools have been established, both adhering to and overlooking the recommended steps. More detailed information on the 11 steps can be found in Spruyt et al. (3). Briefly, Step 1 is to reflect on the variable(s) of interest and targeted sample(s). Step 2 is to consider the research question that the instrument will be used to address. Thus, the goal of this step is to reflect on whether the tool will be suitable to collect the type of data required to address your hypothesis. Steps 3 (response format) and Step 4 (items) build on the two preceding steps. They allow us to reflect not only on “which” questions and “which’” answers assesses the variable(s) of interest, but also on “how” a question is formulated and “how” it can be answered. The common goal of steps 1–4 is that we want the underlying “concepts” and/or “assumptions” contained in the questions, such as language (e.g., jargon), meaning and interpretation of the wording to be identically understood by all respondents. Getting as close as this ideal as possible will minimize errors of comprehension and completion. Step 5 involves piloting of your drafted tools. Piloting also prevents disasters with the actual data collection. In fact, Steps 2–5 should be an iterative process, meaning that we do them repeatedly, until a consensus has been reached among experts and/or respondents with descriptive statistics underpinning those decisions. Assessing the performance of individual test items, separately and as a whole, is Step 6 (item analysis). There are two main approaches to item analysis: classical test theory and the item-response theory, either of which should be combined with missing data analysis. The next step is about identifying the underlying concepts of the tool (Step 7 Structure) because only rarely is a questionnaire unidimensional. Steps 8 and 9 are about assessing the reliability and validity, respectively. Reliability does not imply validity, although a tool cannot be considered valid if it is not reliable! Several statistical, or psychometric, tests allow us to assess a tool’s reliability and validity (cfr. textbooks written on this topic). For instance, validation statistics of the tool may involve content validity, face validity, criterion validity, concurrent validity or predictive validity. Step 10 is about verifying the stability, or robustness, of the aforementioned steps. It is the step in which you assess the significance, inference, and confidence (i.e., minimal measurement error) of your tool, using the sample(s) for which it was designed. Step 11 involves standardization and norm development, allowing large-scale usage of your tool.

This review aims to conclude the trends associated with these questionnaires, and reinforce the importance of certain stages of tool development and highlight the direction of research that would be ideal to follow.

Materials and Methods

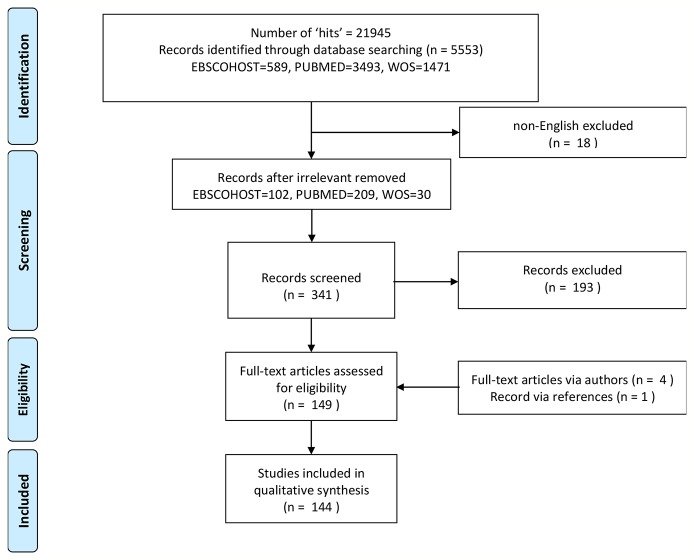

To achieve consistency and retrieve relevant studies to the Spruyt (2, 3) review, the search terms(*) and databases were mirrored; “Sleep” AND (“infant” OR “child” OR “adolescent”) AND (“questionnaire,” “instrument,” “scale,” “checklist,” “assessment,” “log,” “diary,” “record,” “interview,” “test,” “measure”). The databases included PubMed, Web of Science (WOS), and EBSCOHOST (per PRISMA guidelines). Additional limitations to the search criteria were applied for date and age range of the respective study populations. Database-wide searches were conducted between 18th of April 2010 (Spruyt, 2011 publication date of search) and 1st of January 2020. Age categories listed in PubMed filters between 0 and 18 years were also applied to restrict the search to pediatric populations alone. Contrastingly, language criteria were not specified but post hoc constrained to English. Papers in other languages could not be evaluated by one of the authors, in case a consensus on the psychometric evaluation was needed. The search for relevant studies extended to authors in listserver groups PedSleep2.0 and the International Pediatric Sleep Association (IPSA) in order to achieve maximal inclusion. The refinement of these study characteristics ensured that the systematic review would evaluate relevant studies in pediatric tool development, adaptation, and validation. Final search count was sizeable (refer to Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of studies included.

Full-text access was achieved through the literary database “Library Genesis” or author contact if necessary (see Acknowledgments). All flagged citations were then manually screened for relevant keywords in their respective titles, abstracts and methods to further refine studies relevant to the systematic review—these being 11 psychometric steps (2, 3) and 7 sleep categories (sleep quantity, sleep quality, sleep regularity, sleep hygiene, sleep ecology, and sleep treatment) (4). Consequently, independent studies were highlighted and screened, and each study’s descriptive variables were extracted and collated. Any absence of indispensable information regarding the tools use was addressed through contact of authors.

Statistical Analysis

A total of 11 steps (2) and 7 sleep categories (4) were extracted and were statistically analyzed for frequency and descriptive assessment (refer to Tables 1 and 2 ). Any variables unmentioned or neglected were described as “empty,” and tabulated as such in the forthcoming interpretations. Continuous variables will be described as mean values (± standard deviation) and categorical variables will be shown as absolute and relative values. Statistical analyses were performed with Statistica version 13 (StatSoft, Inc. (2009), STATISTICA, Tulsa, OK).

Table 1.

Basic information of studies evaluated.

| Tool acronym | First author | Year | Place of origin | Sample size | Age (years) | Number of questions | Scale | Respondent | Timeframe | Reference has questionnaire | Steps fulfilled |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIS (5) | Chung | 2011 | Hong Kong, China | 1,516 | 12–19 | 8 | three-point Likert | self | in the last month | no | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9 |

| setting : three schools with different levels of academic achievement | |||||||||||

| ASHS (6) | Storfer-Isser | 2013 | Boston, USA | 514 | 16–19 | 32 | six-point ordinal | self | in the past month | no | 1,2,6,7,8,9,10 |

| setting : Cleveland Children's Sleep and Health Study, a longitudinal, community-based urban cohort study | |||||||||||

| ASHS (7) | de Bruin | 2014 | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 186 normal and 112 insomnia | 12–19 | 28 | six-point rating | self | in the past month | yes | 1,2,8,9 |

| setting : a community sample of adolescents and a sample of adolescents with insomnia (registered through a website) | |||||||||||

| ASHS (8) | Chehri | 2017 | Basel, Switzerland | 1,013 | 12–19 | 24 | six-point rating | self | in the past month | no | 1,2,4,6,7,8,9,10 |

| setting : classroom – individual | |||||||||||

| ASHS (9) | Lin | 2018 | Qazvin, Iran | 389 | 14–18 | 24 | six-point rating | self | in the past month | no | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 |

| setting : classroom – individual | |||||||||||

| ASQ (10) | Arroll | 2011 | Auckland, New Zealand | 36 | >15 | 30 | mixed | self | mixed | yes | 1,2,3,4,5,6,9 |

| setting : primary care patients | |||||||||||

| ASWS (11) | Sufrinko | 2015 | north Carolina, USA | 467 | 12–18 | 10 | self | no | 1,2,6,7,8,9,10 | ||

| setting : classroom – individual | |||||||||||

| ASWS (12) | Essner | 2015 | Seattle, USA | 491 | 12–18 | 28 | six-point Likert | self | previous month | no | 1,2,7,8,9 |

| setting : data were pooled from five research studies with heterogeneous samples of adolescents with nondisease-related chronic pain, sickle cell disease, traumatic brain injury, or depressive disorders, as well as adolescents who were otherwise healthy, from three sites in the Northwest and Midwestern United States. | |||||||||||

| BEARS (13) | Bastida-Pozuelo | 2016 | Murcia, Spain | 60 | 2–16 | 7 | yes/no | parent | no | 1,2,4,6,9 | |

| setting : first time visit at National Spanish Health Service's mental healthcare centre | |||||||||||

| BEDS (14) | Esbensen | 2017 | Ohio, USA | 30 | 6–17 | 28 | five-point Likert | parent | in last 6 months | no | 1,2,6,8,9 |

| setting : take-home questionnaires and sleep diary | |||||||||||

| BISQ (15) | Casanello | 2018 | Barcelona, Spain | 87 | 3–30 months | 14 | mixed | parent | yes | 1,2,4,5,6,8,9 | |

| setting : clinic based (self-report and follow-up interview) | |||||||||||

| BRIAN-K (16) | Berny | 2018 | Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil | 373 | 7–8 | 17 | three-point Likert | parent | in the last 15 days | yes | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 |

| setting : classroom – individual | |||||||||||

| CAS-15 (17) | Goldstein | 2012 | New York, USA | 100 | 2–12 | 15 | mixed | clinician | yes | all steps except 10 | |

| setting : children referred to the pediatric otolaryngology outpatient offices for evaluation of snoring and suspected sleep disordered breathing | |||||||||||

| CBCL (18) | Becker | 2015 | Cincinnati, OH, USA | 383 | 6–18 | 7 sleep items | three-point Likert | parent/self | no | 1,2,6,8,9 | |

| setting : referred patients to tertiary-care pediatric hospital | |||||||||||

| CCTQ (19) | Dursun | 2015 | Erzurum, Turkey | 101 | 9–18 | 27 | mixed | parent | on work and free days | no | 1,2,6,8,9 |

| setting : sample from clinical (outpatient psychiatry) and community settings | |||||||||||

| CCTQ (20) | Ishihara | 2014 | Tokyo, Japan | 346 | 3–6 | 27 | mixed | parent | on work and free days | no | 1,2,6,8,9 |

| setting : mailed to parents via kindergartens | |||||||||||

| CCTQ (21) | Yeung | 2019 | Hong Kong, China | 555 | 7–11 | 27 | mixed | parent | no | 1,2,3,4,5,6,8,9 | |

| setting : five primary schools in the Hong Kong SAR | |||||||||||

| CRSP (22) | Cordts | 2016 | Kansas, USA | 155 | 9.82 | 62 | self | no | 1,2,6,7,9,10 | ||

| setting : take-home questionnaire/classroom group | |||||||||||

| CRSP (23) | Meltzer | 2013 | Denver, Colorado, USA | 456 | 8–12 | 60 | mixed | self | mixed | yes | 1,2,4,8,9,10 |

| setting: primary care pediatricians' offices, an outpatient pediatric sleep clinic, community flyers and advertisements, two independent Australian schools, two different pediatric sleep laboratories, and outpatient clinics or inpatient units of a children's hospital for oncology patients | |||||||||||

| CRSP (24) | Meltzer | 2014 | Denver, Colorado, USA | 570 | 13–18 | 76 | mixed | self | mixed | no | 1,2,4,7,8,9,10 |

| setting: from several studies: pediatric sleep clinics at two separate children's hospitals, outpatient clinics and inpatient units of a children's hospital for oncology patients, two independent Australian schools, an Internet based sample of adolescents, including those with asthma (categorized in clinic group) and those without asthma (categorized in community group) | |||||||||||

| CRSP (25) | Steur | 2019 | Amsterdam, Netherlands | n= 619 general n=34 clinic |

7–12 | 26 (total score on 23) | three-point | self | one week | no (English items listed) | 1,4,7,8,9,10,11 |

| setting : online data collection in cooperation with the Taylor Nelson Sofres Netherlands Institute for Public Opinion, an outpatient sleep clinic | |||||||||||

| CRSP-S (26) | Meltzer | 2012 | Denver, Colorado, USA | 388 | 8–12 | 5 | 5-point rating | self | no | 1,2,6,7,8,9,10 | |

| setting : primary care pediatrician's offices: the Sleep Clinic at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), through community flyers and advertisements in the Delaware Valley, through two independent schools in Adelaide, South Australia, while waiting for an overnight polysomnography at CHOP or the Children's Hospital of Alabama, or during outpatient clinic visits or on the inpatient unit at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital | |||||||||||

| CSAQ (27) | Chuang | 2016 | Taichung, Taiwan | 362 | 8–9 | 44 | four-point Likert | parent | no | all steps except 11 | |

| setting : elementary school | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (28) | Markovich | 2015 | Halifax, Canada | 30 | 6–12 | 45 (33 scored question) | three-point Likert | parent | in the previous week | no | 1,2,8,9 |

| setting : data were collected from two larger studies | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (29) | Dias | 2018 | Braga, Portugal | 299 | 2 weeks–12 months | 48 | four-point Likert | parent | mixed | yes | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9 |

| setting : women were contacted at the third trimester of pregnancy; send by email | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (30) | Ren | 2013 | Beijing, China | 912 | 6–12 | 33 | three-point Likert | parent | no | 1,2,6,7 | |

| setting : Parent meeting at primary and elementary students in Shenzhen | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (31) | Liu | 2014 | Chengdu, China | 3,324 | 3–6 | 33 | three-point Likert | parent | a typical week | no | 1,2,6,7,8,9,10 |

| setting : 21 mainland Chinese cities; take-home questionnaire | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (32) | Tan | 2018 | Shanghai, China | 171 | 4–5 | 33 | three-point and four-point Likert | parent | no | 1,2,6,7,8,9,10 | |

| setting : distributed at the schools; take-home questionnaire | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (33) | Waumans | 2010 | Amsterdam Netherlands | 1,502 | 5–12 | 33 | four-point Likert | parent | no | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,10 | |

| setting : primary schools and daycare centers | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (34) | Steur | 2017 | Amsterdam Netherlands | 201 | 2–3 | 33 | three-point Likert | parent | 1-week | no | 1,2,4,6,7,8,10,11 |

| setting : online questionnaire via a Dutch market research agency | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (35) | Mavroudi | 2018 | Thessaloniki, Greece | 112 | 6–14 | 45 | four-point Likert | parent | a “common” recent week | no | 1,2,8,9 |

| setting : patients were ascertained sensitive to a variety of aeroallergens | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (36) | Johnson | 2016 | Florida USA | 310 (177+34+99) | 2–10 | 33 | a 1–3 rating + yes/no | parent | no | 1,2,6,7,8 | |

| setting : enrolled from three study sites : 24-week, multisite randomized controlled trial of parent training (PT) versus parent education; an 8-week randomized trial of a PT program; Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (37) | Sneddon | 2013 | Vancouver, BC, Canada | 105 | 2–5 | 33 | three-point Likert | mother | no | 1,2,6,7,8,9 | |

| setting : early intervention programs, outpatient mental health clinics; general community | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (short) (38) | Masakazu | 2017 | Tokyo, Japan | 178; 432; 330 | 6–12 | 19 | three-point rating | parent | a typical recent week | no | 1,2,3,4,5,6,8,9,10 |

| setting : different collection times/settings: elementary school; pediatric psychiatric hospital; community | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (39) | Schlarb | 2010 | Tübingen, Germany | 298;45 | 4–10 | 48 | three-point + yes/no | parent | no | 1,2,4,6,7,8,9 | |

| setting : community sample via schools, clinical sample | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (40) | Silva | 2014 | Lisbon, Portugal | 315 | 2–10 | 33 | three-point rating | parent | a recent more typical week | no | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9 |

| setting : community sample | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (41) | Lucas-de la Cruz | 2016 | Cuenca, Spain | 286 | 4–7 | 33 | three-point rating | parent | no | 1,2,4,6,7,8,9 | |

| setting : cross-over cluster randomized trial from 21 schools | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (42) | Fallahzadeh | 2015 | Kashan, Iran | 300 | 5–10 | 33 | three-point rating | parent | no | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9 | |

| setting : public and private schools | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (43) | Loureiro | 2013 | Lisbon, Portugal | 574 | 7–12 | 26 | three-point Likert | parent | no | 1,2,4,5,6,8,9 | |

| setting : community and clinical samples | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (short) (44) | Bonuck | 2017 | Boston, Masacheusettes | 151;218 | 4–10; 24–66 months | 23 | parent | no | 1,2,6,9 | ||

| setting : clinic sample data (two datatest were reused for this study: Owens (1997/8) and Goodlin-Jones (2003-5), respectively) | |||||||||||

| CSHQ (14) | Esbensen | 2017 | Cincinnati, OH, USA | 30 | 6–17 | 33 | three-point Likert | parent | no | 1,2,6,8,9 | |

| setting: community-based study in children with Down syndrome | |||||||||||

| CSM (45) | Jankowski | 2015 | Warsaw, Poland | 952 | 13–46 | 13 | mixed | self | yes | 1,2,4,6,8,9 | |

| setting : residents from Warsaw and Mielec districts | |||||||||||

| CSRQ (46) | Dewald | 2012 | Amsterdam Netherlands | 166; 236 | 12.2–16.5; 13.3–18.9 | 20 | ordinal response categories ranging from 1 to 3 | self | previous 2 weeks | no | 1,2,4,6,7,8,10 |

| setting : five high schools in and around Amsterdam and from five high schools in Adelaide and Outer Adelaide | |||||||||||

| CSRQ (47) | Dewald-Kaufmann | 2018 | Amsterdam Netherlands | 298 | 20 | ordinal response categories ranging from 1 to 3 | self | previous 2 weeks | no | 1,2,9,11 | |

| setting : participants were recruited from high schools around Amsterdam; referred to the Centre for Sleep–Wake Disorders and Chronobiology of Hospital Gelderse Vallei in Ede, the Netherlands; adolescents who received cognitive behavioural therapy for their sleep onset and maintenance problems (see de Bruin et al) | |||||||||||

| CSWS (48) | LeBourgeois | 2016 | Boulder, CO, USA | 161; 485; 751; 55;85 | 2–8 (different across studies) | 25 (different across studies) | four-point (different across studies) | parent | no | all steps except 11 | |

| setting : 5 studies with independent samples (different across studies) | |||||||||||

| DBAS (49) | Lang | 2017 | Basel, Switzerland | 864 | 17.9 | 16 | 10-point Likert | self | no | 1,2,4,6,7,8,9,10 | |

| setting : students in vocational education and training; in a classroom setting | |||||||||||

| DBAS (50) | Blunden | 2012 | Queensland Australia | 134 | 11–14 | 10 | mixed | self | no | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 | |

| setting : From sleep education intervention | |||||||||||

| ESS (51) | Krishnamoorthy | 2019 | Puducherry, India | 789 | 10–19 | 8 | four-point Likert | self | no | all steps | |

| setting : villages of rural Puducherry, a union territory in South India | |||||||||||

| ESS (52) | Crabtree | 2019 | Memphis, Tennessee | 66 | 6–20 | 8 | four-point Likert | self | in various everyday situations | no | 1,2,8,9,11 |

| setting : children and young adults (ages 6 to 20 years) were assessed by the M-ESS after surgical resection, if performed, and before proton therapy | |||||||||||

| ESS-CHAD (53) | Janssen | 2017 | Victoria, Australia | 297 | 12–18 | 8 | four-point Likert | self | thinking of the last two weeks | no | 1,2,6,7,8,9,10 |

| setting : Part of a broader research project; schools in regional Victoria (qualtrics survey) | |||||||||||

| FoSI (54) | Brown | 2019 | Washington, DC, USA | 147 | 14–18 | 11 | five-point Likert | self | last month | no | 1,2,6,7,8,9,10 |

| setting : two school-based health centers in the Washington Metropolitan Area | |||||||||||

| I SLEEPY (55) | Kadmon | 2014 | Ontairo, Canada | 150 | 3–18 | 8 | yes/no | parent/self | yes | 1,2,4,5,6,9 | |

| setting : referred for evaluation at a pediatric sleep clinic | |||||||||||

| IF SLEEPY (55) | Kadmon | 2014 | Ontairo, Canada | 150 | 3–18 | 8 | yes/no | parent/self | yes | 1,2,4,5,6,9 | |

| setting : referred for evaluation at a pediatric sleep clinic | |||||||||||

| I'M SLEEPY (55) | Kadmon | 2014 | Ontairo, Canada | 150 | 3–18 | 8 | yes/no | parent/self | yes | 1,2,4,5,6,9 | |

| setting : referred for evaluation at a pediatric sleep clinic | |||||||||||

| ISI (5) | Chung | 2011 | Hong Kong, China | 1,516 | 12–19 | 8 | five-point Likert | self | in last 2 weeks | no | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9 |

| setting : three schools with different levels of academic achievement | |||||||||||

| ISI (56) | Kanstrup | 2014 | Solna, Sweden | 154 | 10–18 | 5 | five-point rating | self | past 2 weeks | no | 1,2,4,6,8,9 |

| setting : patients with chronic pain referred to a tertiary pain clinic upon first visit | |||||||||||

| ISI (57) | Gerber | 2016 | Basel, Switzerland | 1,475 adolescents, 862 university students and 533 adults | 11–16 | 7 | eight-point Likert | self | yes | 1,2,4,6,7,8,9,10 | |

| setting : 3 cross-sectional studies; via schools | |||||||||||

| JSQ (58) | Kuwada | 2018 | Osaka, Japan | 4,369; 100 | 6–12 | 38 | mixed (6 point intensity rating) | parent | no | 1,2,7,8,9,10,11 | |

| setting : 17 elementary schools; 2 pediatric sleep clinic | |||||||||||

|

JSQ (preschool) (59) |

Shimizu | 2014 | Osaka, Japan | 2,998;102 | 2–6 | 39 | six-point Likert | parent | no | 1,2,4,6,7,8,9,11 | |

| setting : private kindergarten, nursery school, and recipients of regular physical examinations at the age of 3 years; two pediatric sleep clinics | |||||||||||

| LSTCHQ (60) | Garmy | 2012 | Lund, Sweden | 116 child respondents; 44 parent respondents | 6–13 | 11 | mixed | parent/self | yes | 1,2,4,5,8,9 | |

| setting : school-based distriution | |||||||||||

| MCTQ (61) | Roenneberg | 2003 | Basel, Switzerland | 500 (142 being <21years) | 6–18 | ~9* | seven-point rating; mixed | self | free/work days | yes | 1,2,5,6 |

| setting : distributed in Germany and Switzerland in high schools, universities, and the general population. This paper was added because of its relevance despite being outside the timeframe of the current review | |||||||||||

| MEQ (62) | Cavallera | 2015 | Milan, Italy | 292 | 11–15 | 17 | self | no | 1,2,4,5,7,8,9 | ||

| setting : convenience school-based samples | |||||||||||

| (r)MEQ (63) | Danielsson | 2019 | Uppsala, Sweden | 671 | 16–26 | 5 | self | no | 1,2,6,7,8,9 | ||

| setting : selected randomly from the Swedish Population Register | |||||||||||

| aMEQ (64) | Rodrigues | 2016 | Aveiro district, Portugal | 300 | 12–14 | 19 | mixed | self | no | 1,2,4,5,6,8,9,11 | |

| setting: 80% public and 20% private schools from the district of Aveiro | |||||||||||

| aMEQ-R (65) | Rodrigues | 2019 | Aveiro district, Portugal | n1=300 (same 2016) n2= 217 |

12–14 | 10 | mixed | self | no | 1,2,4,5,6,8,9,11 | |

| setting: several schools of the Aveiro district | |||||||||||

| MESC (66) | Diaz-Morales | 2015 | Madrid, Spain | 5,387 | 10–16 | self | no | 1,2,4,6,7,8,9,10 | |||

| setting: public high schools in Madrid and the surrounding area | |||||||||||

| MESSi (67) | Demirhan | 2019 | Sakarya, Turkey | 1,076 | 14–47 | 15 | five-point Likert | self | yes | 1,4,5,7,8,9,10 | |

| setting: high school and university students | |||||||||||

| MESSi (68) | Weidenauer | 2019 | Tuebingen, Germany | 215 | 11–17 | 15 | five-point Likert | self | yes | 1,6,8,9,10 | |

| setting: three different gymnasia (highest stratification level of school teaching) in SW Germany, Baden-Wuerttemberg | |||||||||||

| My Sleep and I (69) | Rebelo-Pinto | 2014 | Lisbon, Portugal | 654 | 10–15 | 27 | five-point Likert | self | no | 1,2,3,4,7,8,9,10 | |

| setting: schools in Portugal part of project Sleep More to Read Better | |||||||||||

| My children's sleep' (69) | Rebelo-Pinto | 2014 | Lisbon, Portugal | 612 | 21–68 | 27 | five-point Likert | parent | no | 1,2,3,4,7,8,9,10 | |

| setting: schools in Portugal part of project Sleep More to Read Better | |||||||||||

| NARQoL-21 (70) | Chaplin | 2017 | Gothenburg, Sweden | 158 | 8–13; 15–17 | 21 | five-point Likert | self | no | all steps | |

| setting : patient and control group | |||||||||||

| NSD (71) | Yoshihara | 2011 | Tochigi, Japan | 40 | 6 months–6 years | 2 | parent | diary | yes | 1,2,3,4,5,6 | |

| setting : take home diary | |||||||||||

| NSS (72) | Ouyang | 2019 | Beijing, China | n=53 pediatric n= 69 adult | >8 years | 15 | no | 1, 2, 7, 8, 9 | |||

| setting : sleep lab | |||||||||||

| OSA Screening Questionnaire (73) | Sanders | 2015 | Southampton, UK | infancy to 6 years | 33 | parent | over a week | yes | 1,2,3,4,5,6,9 | ||

| setting : via a local Down syndrome parent support group | |||||||||||

| OSA-18 Questionnaire (74) | Huang | 2015 | Hsinchu, Taiwan | 163 | 6–12 | 18 | seven-point ordinal | parent | past 4 weeks | yes (English) | 1,2,4,7,8,9,10 |

| setting : via schools | |||||||||||

| OSA-18 Questionnaire (75) | Kang | 2014 | Taipei, Taiwan | 109 | 2–18 | 18 | seven-point ordinal | parent | yes | 1,2,4,6,8,9 | |

| setting : recruited from the respiratory, pediatric, psychiatric, and otolaryngologic clinics | |||||||||||

| OSA-18 Questionnaire (76) | Bannink | 2011 | Rotterdam, Netherlands | 119 patients; 162 (child);459 parent | 2–18 | 18; OSA-12 in children, OSA-18 in parents | seven-point ordinal | parent/self | yes | 1,2,4,6,8,9 | |

| setting : patients with syndromic craniosynostosis; convenience sample of parents | |||||||||||

| OSA-18 Questionnaire (77) | Mousailidis | 2014 | Athens, Greece | 141 | 3–18 | 18 | seven-point ordinal | parent | yes | 1,2,4,6,8,9 | |

| setting : children who were referred for overnight polysomnography at the Sleep Disorders Laboratory | |||||||||||

| OSA-18 Questionnaire (78) | Fernandes | 2013 | Guimarães, Portugal | 51 | 2–12 | 18 | seven-point ordinal | parent | past 4 weeks | yes (English) | 1,2,4,5,6,8,9 |

| setting : sleep clinic | |||||||||||

| OSA-18 Questionnaire (79) | Chiner | 2016 | Alicante, Spain | 60 | 2–14 | 18 | seven-point ordinal | parent | 4 weeks | yes | 1,2,4,6,7,8,9 |

| setting : children with suspected apnea-hypopnea syndrome were studied with polysomnography | |||||||||||

| OSA-5 Questionnaire (short) (80) | Soh | 2018 | Melbourne, Australia | 366 and 123 | 2–17.9 | 5 | four-point Likert | parent | past 4 weeks | yes | all steps except 11 |

| setting: Melbourne Children's Sleep Centre for polysomnography | |||||||||||

| OSD-6 QoL Questionnaire (81) | Lachanas | 2014 | Larissa, Greece | 91 | 3–15 | 6 | seven-point ordinal | parent | yes (Greek and English) | 1,2,4,5,6,8,9 | |

| setting : children undergoing polysomnography | |||||||||||

| oSDB and AT (82) | Links | 2017 | Baltimore, USA | 32 | 39 | three-point rating | parent | yes | 1,2,4,6,8,9 | ||

| setting : online Questionnaire | |||||||||||

| OSPQ (83) | Biggs | 2012 | Adelaide, Australia | 1,904 | 5–10 | 26 | four-point Likert | parent | last typical school week | no | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,10,11 |

| setting : via 32 elementary schools in Adelaide | |||||||||||

| PADSS (84) | Arnulf | 2014 | Paris, France | 73; 98 | >15 | 17 | self | no | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 | ||

| setting : patients with sleepwalking or sleep terror referred to the sleep disorder unit; controls | |||||||||||

| PDSS (85) | Felden | 2015 | Curitiba, Brazil | 90 | 10–17 | 8 | five-point Likert | self | yes | 1,2,4,5,8,9 | |

| setting : two private schools | |||||||||||

| PDSS (86) | Komada | 2016 | Tokyo, Japan | 492 | 11–16 | 8 | self | no | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9 | ||

| setting : one elementary school, one junior high school and one high school, located in suburbs of Japan | |||||||||||

| PDSS (87) | Bektas | 2015 | Izmir, Turkey | 522 | 5–11 | 8 | four-point Likert | self | no | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 | |

| setting : students were in grade 5-11 | |||||||||||

| PDSS (88) | Ferrari Junior | 2018 | Florianópolis, SC, Brazil | 773 | 14–19 | 8 | five-point Likert | self | no | 1,7,8,9,10 | |

| setting : state schools of Paranaguá, Paraná | |||||||||||

| PDSS (89) | Randler | 2019 | Petrozavodsk, Russia | n1= 285 n2= 267 n3= 204 |

7–12 | 8 | five-point Likert | self | yes | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 | |

| setting : Schools from six different settlements located in North-Western Russia (Murmansk region) participated in the study during our framework project "Sleep Health in Russian Arctic" | |||||||||||

| Pediatric Sleep CGIs (90) | Malow | 2016 | Nashville, USA | 20 | 5.3 | 14 | seven-point rating | parent | yes (link) | 1,2,4,5,6,9 | |

| setting : participants in a 12-week randomized trial of iron supplementation in children with autism spectrum disorders | |||||||||||

| PedsQL (fatigue scale) (91) | Al-Gamal | 2017 | Amman, Jordan | 70 | 5–18 | 18 | three- and five-point Likert | self | no | 1,2,4,5,6,8,9 | |

| setting : oncology outpatient clinic | |||||||||||

| PedsQL (fatigue scale) (92) | Qimeng | 2016 | Guangzhou, China | 125 | 2–4 | 18 | five-point Likert | parent | no | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9 | |

| setting : diagnosed to have acute leukemia for 1 month at the least | |||||||||||

| PedsQL(fatigue scale) (93) | Nascimento | 2014 | São Paolo, Brazil | 216; 42 children (8–12 years), 68 teenagers (13–18 years), and 106 caregivers (parents or guardians) | 8–18 | 18 | five-point Likert | parent/self | no | 1,2,4,6,7,8,9,10 | |

| setting : oncology inpatient and outpatient pediatric clinics | |||||||||||

| PISI (94) | Byars | 2017 | Cincinnati, OH, USA | 462 | 4–10 | 6 | six-point Likert | parent | yes | 1,2,4,6,7,8,9,10 | |

| setting : behavioral sleep medicine evaluation clinic | |||||||||||

| PNSSS (95) | Whiteside-Mansell | 2017 | Little Rock, Arkansas, USA | 72 | 1 week to 28 weeks | 14 | four-point scale | professional | no | 1,2,8 | |

| setting : a naturalistic study of participants enrolled in two home visitation support programs | |||||||||||

| PosaST (96) | Pires | 2018 | Porte Alegre, Brazil | 60 | 3–9 | 6 | five-point rating | self | yes | 1,2,4,5,8,9 | |

| setting : children undergoing polysomnography | |||||||||||

| PPPS (97) | Finimundi | 2012 | Porto Alegre, Brasil | 144 | 10–17 | mixed | five-point rating | self | no | 1,2,9 | |

| setting : adolescent students attending elementary school in two public schools in the state of Rio Grande do Sul (municipalities of Esteio and Farroupilha – great Porto Alegre, and Serra Gaúcha | |||||||||||

| P-RLS-SS (98) | Arbuckle | 2010 | Cheshire, United Kingdom | cognitive debriefing interviews with 21 of the same children/adolescents and 15 of their parents | 6–17 | 26 morning and 28 evening items | Wong and Baker pain faces scale | parent/self | no | 1,2,4,5,6 | |

| setting : four pediatric sleep disorders specialists | |||||||||||

| PROMIS (99) | van Kooten | 2016 | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 6 experts, 24 adolescents and 7 parents | 12–18 | 27 (PROMIS-SD), 16 (PROMIS-SRI) | through Computerized AdaPOINTive Testing | self/parent/expert | no | 1,2,9 | |

| setting : distributed to the adolescents in the classroom | |||||||||||

| PROMIS (100) | van Kooten | 2018 | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 1,046 | 11–19 | 27 (PROMIS- Sleep Disturbance), 16 (PROMIS- Sleep-Related Impairment) | Self | no | 1,2,6,7,9,10 | ||

| setting : online; schools from all educational levels and from different regions of the Netherlands | |||||||||||

| PROMIS (101) | Forrest | 2018 | Philadelphia, PA, USA | 1,104 children (8–17 years old) and 1,477 parents of children 5–17 years old | 5–17 | 43; the final item banks included 15 items for Sleep Disturbance and 13 for Sleep-Related Impairment | frequency-based (1: never, 2: almost never, 3: sometimes, 4: almost always, 5: always) | self/parent | 7-day | yes | 1,2,6,7,8,9,10 |

| setting : a convenience sample of children and parents recruited from a pediatric sleep clinic | |||||||||||

| PROMIS (102) | Bevans | 2019 | Philadelphia, PA, USA | 8 expert sleep clinician-researchers, 64 children ages 8–17 years, and 54 parents of children ages 5–17 years | children ages 8–17 and parents of children ages 5–17. | The final item pool contains 43 child-report items and 49 parent-report items | five-point Likert | Self/Parent | In the past 7 days | yes | 1,2,3,4,5,6,9 |

| setting : A preliminary child sleep health conceptual framework was generated based on the two PROMIS Adult Sleep Health item banks. Thereafter, the framework was refined based on expert and child and parent interviews | |||||||||||

| PSIS (103) | Smith | 2014 | Texas, USA | 155 | 3–5 | 12 | five-point Likert | parent | no | 1,2,6,8,9 | |

| setting : identified using a commercial mailing list and print advertisements distributed throughout local schools, daycares, community centers, and health care providers | |||||||||||

| PSQ (104) | Ishman | 2016 | Ohio, USA | 45 | 16.7 | 22 | yes/no/don't know | parent | no | 1,2,6,8 | |

| setting : teen-longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery (Teen-LABS) participants at high-risk for obstructive sleep apnea | |||||||||||

| PSQ (105) | Yüksel | 2011 | Manisa, Turkey | 111 | 2–18 | 22 | yes/no and I don't know | parent | no | 1,2,4,5,6,8,9 | |

| setting : pediatric allergy and pulmonology outpatient department | |||||||||||

| PSQ (106) | Bertran | 2015 | Santiago, Chile | 83 | 0–15 | 22 | yes/no/don't know | parent | no | 1,2,6,7 | |

| setting: habitually snoring children referred for polysomnography | |||||||||||

| PSQ (107) | Hasniah | 2012 | Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | 192;554 | 6–10 | 22 | "yes=1," "No=0," and "Don't know=Missing" | parent | no | 1,2,4,5,6,8,9 | |

| setting : part of the national epidemiological study of the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in Malaysian school children | |||||||||||

| PSQ (108) | Chan | 2012 | Hong Kong, China | 102 | 2–18 | 22 | yes/no/don't know | parent | no | 1,2,9,11 | |

| setting : underwent overnight sleep polysomnography studies for suspected OSA in the sleep laboratory | |||||||||||

| PSQ (109) | Ehsan | 2017 | Cincinatti, USA | 160 | 2–18 | 22 | yes/no/don't know | parent | no | 1,2,6,9 | |

| setting : using an existing clinical database encompassing all children referred to the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Sleep Center for polysomnography | |||||||||||

| PSQ (110) | Li | 2018 | Beijing, China | 9,198 | 3.0–14.4 | 22 | yes/no/don't know | parent | no | 1,2,6,7,8,9 | |

| setting : 11 kindergartens, 7 primary schools and 8 middle schools from 7 districts of Beijing, China | |||||||||||

| PSQ (111) | Longlalerng | 2018 | Chiang Mai, Thailand | 62 | 7–18 | 22 | yes/no/don't know | parent | no | 1,2,4,5,8,9 | |

| setting : clinic based retrieval classified as overweight or obese according to the International Obesity Task Force and diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea | |||||||||||

| PSQ (112) | Raman | 2016 | Ohio, USA | 636 | 4–25.5 | 36 | parent | yes | 1,2,4 | ||

| setting : patients scheduled for a sleep study | |||||||||||

| PSQ (113) | Certal | 2015 | Porto, Portugal | 180 | 4–12 | 22 | yes/no | self | yes | 1,2,4,5,6,8,9 | |

| setting : via schools north Portugal | |||||||||||

| PSQ (114) | Jordan | 2019 | Paris, France | 201 | 2–17 | 22 | "yes," "no" or "don't know," | parent | yes | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 | |

| setting : admitted to the Odontology Center of the Rothschild Hospital (Assistance Publique e Hopitaux de Paris) | |||||||||||

| PSQI (115) | Passos | 2017 | Pernambuco, Brazil | 309 | 10–19 | 19 | 0–3 rating | self | no | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 | |

| setting : subjects who engaged in amateur sports practice | |||||||||||

| PSQI (116) | Raniti | 2018 | Melbourne, Australia | 889 | 12.08–18.92 | 18 | four-point Likert scale | self | 1 month | no | 1,7,8,9,10 |

| setting : 14 Australian secondary schools | |||||||||||

| RLS (117) | Schomöller | 2019 | Potsdam, Germany | 33 (11 RLS) | 6–12 and 13–18 | 12 | mixed | self/parent | yes | 1,2,3,4,6,8,9 | |

| setting : with the support of medical somnologists, who recruited pediatric patients from their practice or sleep laboratories, newsletter announcements in the Restless Legs Association journal, and via local selfhelp groups. | |||||||||||

| SDIS (118) | Graef | 2019 | Cincinnati, Ohio | 392 | 2.5–18.99 | SDIS-C, 41 items, 2.5–10 years; SDIS-A, 46 items, 11–18 years | seven-point Likert scale | parent | no | 1,9 | |

| setting : Youth with insomnia, of whom 392 underwent clinically indicated diagnostic PSG within ± 6 months of SDIS screening | |||||||||||

| SDPC (119) | Daniel | 2016 | Philadelphia, USA | 20;6 | 3–12 | 41 | 0–4 rating | parent | Interview modelling | no | 1,2,4,6,9 |

| setting : parents of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and medical providers | |||||||||||

| SDSC (120) | Huang | 2014 | Guangzhou, China | 3,525 | 5–16 | 26 | five-point scale | parent | six months | no | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 |

| setting : selected from five primary schools in Shenyang | |||||||||||

| SDSC (121) | Putois | 2017 | Sierre, Switzerland | 447 | 4–16 | 25 | five-point scale | parent | six months | yes | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 |

| setting: schools; pediatric sleep clinic | |||||||||||

| SDSC (122) | Saffari | 2014 | Isfahan, Iran | 100 | 6–15 | 26 | five-point scale | parent | six months | no | 1,2,4,5,6,8,9 |

| setting: primary and secondary schools in Isfahan City, Iran | |||||||||||

| SDSC (14) | Esbensen | 2017 | Cincinnati, OH, USA | 30 | 6–17 | 26 | five-point scale | parent | 6 months | no | 1,2,6,8,9 |

| setting: part of a larger community-based study down syndrome sample | |||||||||||

| SDSC (123) | Cordts | 2019 | Portland, OR, USA | 69 | 3–17 | 26 | five-point Likert | parent | 6 months | no | 1,6,8,9 |

| setting: longitudinal pediatric neurocritical care programs at two tertiary academic medical centers within 3 months of hospital discharge | |||||||||||

| SDSC (124) | Mancini | 2019 | Western Australia, Australia | 307 | 4–17 | 26 | five-point Likert | parent | 6 months | no | 1,2,10 |

| setting: recruited via the Complex Attention and Hyperactivity Disorders Service (CAHDS), in Perth, Western Australia | |||||||||||

| SDSC* (125) | Moo-Estrella | 2018 | Yucatán, Mexico | 838 | 8–13 | 25 | number of days : 0 = 0 days, 1 = 1–2 days, 2 = 3–4 days, 3 = 5–6 days, and 4 = 7 days. | self | during the last week | no | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 |

| setting : between the third and sixth grades of elementary school, recruited by convenience sampling | |||||||||||

| SHI (126) | Ozdemir | 2015 | Konya, Turkey | 106 patients with major depression; 200 volunteers recruited from community sample | 16–60 | 13 | Always, Frequently, Sometimes, Rarely, Never | self | no | 1,2,6,7,8,9,10 | |

| setting : university based retrieval | |||||||||||

| SHIP (127) | Rabner | 2017 | Boston, USA | 1,078 | 7–17 | 15 | three-point Likert | parent/self | no | 1,2,6,8,9 | |

| setting: parents and children each completed questionnaires individually within 1 week prior to the child's multidisciplinary headache clinic evaluation | |||||||||||

| Sleep Bruxism (128) | Restrepo | 2017 | Medellın, Colombia | 37 | 8–12 | 1 | yes/no | parent | 5-day diary | yes (English) | 1,2,4 |

| setting : recruited from the clinics at Universidad CES | |||||||||||

| SNAKE (129) | Blankenburg | 2013 | Datteln, Germany | 224 | <10 | 54 | 1–4 rating (mixed) | parent | yes (English) | all steps | |

| setting : children with severe psychomotor impairment; questionnaire-based, multicenter, cross-sectional survey | |||||||||||

| SQI (5) | Chung | 2011 | Hong Kong, China | 12–19 | 8 | three-point Likert | self | In past 3 months | no | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 | |

| setting: three schools with different levels of academic achievement | |||||||||||

| SQ–SP (130) | Maas | 2011 | Maastricht, Netherlands | 345 | 1–66 | 45 | seven-point Likert | parent | last three months | yes | 1,2,6,7,8,9,10, |

| setting: individuals who consulted the sleep clinic for individuals with ID; individuals from a control group who attended a special day care center, special school or adult activity center for individuals with ID; participants of two published studies Maas et al., 2008, 2009); individuals who consulted a psychiatric clinic for children and adolescents with ID | |||||||||||

| SQS-SVQ (131) | Önder | 2016 | Sakarya, Turkey | 1,198 | 11–15 | 15* | self | yes | 1,2,4,7,8,9,10 | ||

| setting: an instrument adaptation study with different groups | |||||||||||

| SRSQ (132) | van Maanen | 2014 | AmsterdamNetherlands | 951;166;236;144;66 | 14.7 (mean) | 9 | three-point ordinal | self | previous 2 weeks | no | 1,2,6,8,9 |

| setting : various samples from the general and clinical populations; online and paper and pencil | |||||||||||

| SSR (133) | Orgilés | 2013 | Alicante, Spain | 1,228 | 8–12 | 26 | three-point | self | yes | 1,2,4,6,7,8,9,10 | |

| setting : 9 urban and suburban schools; per 20 in group | |||||||||||

| SSR (43) | Loureiro | 2013 | Lisbon, Portugal | 306 | 7–12 | 26 | three-point | self | no | 1,2,4,5,6,8,9 | |

| setting : community and clinical samples | |||||||||||

| SSSQ (134) | Yamakita | 2014 | Koshu, Japan | 58 | 9–12 | Please note your bedtime and wake time on both weekdays and weekends | self | log | no | 1,2,8,9 | |

| setting : a typical elementary school in Koshu City | |||||||||||

| STBUR (135) | Tait | 2013 | Michigan, USA | 337 | 2–14 | 5 | yes/no, and don't know | parent | yes | 1,2,3,4,6,7 | |

| setting : parents of children scheduled for surgery | |||||||||||

| STQ (136) | Tremaine | 2010 | Adelaide, Australia | 65 | 11–16 | 18 | time | self | no | 1,2,9 | |

| setting : 3 different private (independent) schools in South Australia | |||||||||||

| The Children's Sleep Comic (137) | Schwerdtle | 2012 | Landau, Germany | 201 | 5–10 | 37 | tick in applicable square | self | no (examples) | 1,2,4,9 | |

| setting : three primary schools in Germany (group) | |||||||||||

| The Children's Sleep Comic (138) | Schwerdtle | 2015 | Würzburg, Germany | 176;393 | 5–11 | 20 | tick in applicable square | parent/self | no (examples) | 1,2,3,4,6,8,9,11 | |

| setting : three primary schools in Germany (group) | |||||||||||

| TuCASA (139) | Leite | 2015 | São Paolo, Brazil | 62 | 4–11 | 13 | parent | yes | 1,2,4,8,9 | ||

| setting : sleep-disordered breathing diagnosed by polysomnography and controls | |||||||||||

| YSIS (140) | Liu | 2019 | Shandong Province, China | 11,626 | 15.0 ±1.5 | 8 | five-point Likert | self | past month | yes | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 |

| setting : Shandong Adolescent Behavior and Health Cohort, five middle and three high schools in three counties of Shandong Province, China | |||||||||||

Steps: 1: purpose; 2: research question; 3: response format; 4: generate items; 5: pilot; 6: item-analysis, nonresponse; 7: structure; 8 reliability; 9: validity; 10: confirmatory analyses; 11: standardize and develop norms

Table 2.

Overview of psychometric analyses performed.

| Tool acronym |

NPTA | in Spruyt et al | Sleep categories | Factor analysis | Reliability analyses | Validity analyses | Confirmatory analysis | ROC | Normative values or cutoffs | Clinical classification | Specific population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIS (5) | P | quality | structure | test-retest; internal | convergent/discriminant | yes; a total score ≥7 |

original AIS developed per ICD-10 | DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of insomnia by interview | |||

| ASHS (6) | P | yes | regularity, hygiene, ecology, | structure | internal | convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | ||||

| ASHS (7) | P | yes | regularity, hygiene, ecology, | test-retest, internal | construct; convergent/discriminant | insomnia per DSM-IV-TR | |||||

| ASHS (8) | PT (Farsi) |

yes | regularity, hygiene, ecology | structure | test-retest, internal | convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | ||||

| ASHS (9) | PT (Persian) | yes | regularity, hygiene, ecology | structure | test-retest, internal | content; construct | confirmatory | ||||

| ASQ (10) | N | quality, sleepiness | face | ICSD | |||||||

| ASWS (11) | P | yes | quantity, hygiene | structure | internal | content; construct | confirmatory | ||||

| ASWS (12) | P | yes | quantity, hygiene | structure | internal | construct | |||||

| BEARS (13) | PT (Spanish) | yes | quantity, quality, sleepiness | criterion | ICD-10 diagnoses assigned to these children, prior to the commencement of the parent group intervention were: F90, F98.2, F93.3, F80.1, F93.0, Z62 |

||||||

| BEDS (14) | A | yes | quantity, quality, hygiene, ecology | test-retest; internal | construct; convergent/discriminant | Down syndrome | |||||

| BISQ (15) | T (Spanish) | yes | quantity, hygiene | test-retest; interrater/observer | content; construct | ||||||

| BRIAN-K (16) | N | regularity, hygiene, | structure | internal | content; construct | ||||||

| CAS-15 (17) | P | quality | structure | test-retest; internal; interrater/observer | construct; criterion; convergent/discriminant | yes; a score ≥32 | |||||

| CBCL (18) | P | yes | quantity, quality,sleepiness | test-retest | convergent/discriminant | patients were diagnosed with sleep disorders according to ICSD-2 | |||||

| CCTQ (19) | T (Turkish) | quantity, regularity | internal | content | |||||||

| CCTQ (20) | P | quantity, regularity | test-retest; internal | criterion | |||||||

| CCTQ (21) | PT (Chinese) | quantity, regularity | test-retest. internal | content; construct | |||||||

| CRSP (22) | P | quantity, quality, sleepiness, hygiene | structure | content; construct | confirmatory | ||||||

| CRSP (23) | N | quantity, quality, sleepiness, hygiene | internal | construct; criterion; convergent/discriminant | |||||||

| CRSP (24) | P | quantity, quality, sleepiness, hygiene | structure | test-retest; internal | construct; criterion; convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | |||||

| CRSP (25) | PT | quantity, quality, sleepiness, hygiene | structure | internal | convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | mean (SD)/n(%) | ||||

| CRSP-S (26) | P | sleepiness | structure | test-retest; internal | construct; convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | |||||

| CSAQ (27) | N | quantity, quality, sleepiness | structure | test-retest; internal; interrater/observer | content; construct; convergent/discriminant | ||||||

| CSHQ (28) | P | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | test-retest | construct; criterion | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | ||||||

| CSHQ (29) | AT (Portuguese) | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | structure | test-retest; internal | convergent/discriminant | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | |||||

| CSHQ (30) | P | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | structure | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | |||||||

| CSHQ (31) | P | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | structure | test-retest; internal | content; construct | confirmatory | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | ||||

| CSHQ (32) | P | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | structure | internal | content; construct | confirmatory | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | ||||

| CSHQ (33) | T (Dutch) | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | structure | test-retest; internal; interrater/observer | confirmatory | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | |||||

| CSHQ (34) | T (Dutch) | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | structure | internal | confirmatory | a mean total CSHQ score of 41.9±5.6 | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | ||||

| CSHQ (35) | A | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | internal | convergent/discriminant | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | allergic rhinitis | |||||

| CSHQ (36) | A | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | structure | internal | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | autism spectrum disorder | |||||

| CSHQ (37) | P | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | structure | internal | criterion | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | |||||

|

CSHQ (short) (38) |

A | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | internal | convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | yes; a total CSHQ score of ≥ 24 | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | clinical samples diagnoses based on the DSM-IV: pervasive developmental disorders, attention-deficit and disruptive behavior disorders, anxiety disorders; depressive disorders, and others and also without psychiatric disorder |

|||

| CSHQ (39) | PT (German) | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | structure | test-retest; internal | content | yes; per subscale provided | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | sleep disorders per ICSD II | |||

| CSHQ (40) | T (Portuguese) | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | structure | test-retest; internal | face | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | |||||

| CSHQ (41) | PT (Spanish) | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | structure | test-retest; internal | face; content; construct | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | |||||

| CSHQ (42) | T (Persian) | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | structure | test-retest; internal | face; content; construct; convergent/discriminant | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | |||||

| CSHQ (43) | T (Portuguese) | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | test-retest; internal | content | yes; a cutoff total score of 44 | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | ICSD II for Sleep Related Breathing Disorder, Parasomnia, Behavioral Sleep Disorder | ||||

|

CSHQ (short) (44) |

A | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | convergent/discriminant | yes; a cutoff total score of 30 | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | ||||||

| CSHQ (14) | P | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | internal | construct; convergent/discriminant | original was designed to identify sleep problems based on ICSD-1 | Down syndrome | |||||

| CSM (45) | T (Polish) | regularity, sleepiness | internal | content; construct | accumulated percentile distribution | ||||||

| CSRQ (46) | T (English) | yes | quantity, regularity, sleepiness | structure | internal | confirmatory | |||||

| CSRQ (47) | P | quantity, regularity, sleepiness | criterion | yes; ≥35; optimal sensitivity : 27.5; optimal specificity: 50.5 | |||||||

| CSWS (48) | P | yes | quantity, regularity | structure | test-retest; internal | content; construct | confirmatory | children with Sleep-Onset Association Problems per ICSD | |||

| DBAS (49) | T (German) | quantity, quality, regularity | structure | internal | content | confirmatory | |||||

| DBAS (50) | P | quantity, quality, regularity | structure | test-retest; internal | content | ||||||

| ESS (51) | PT (Tamil) | yes | sleepiness | structure | internal | face; content; construct | confirmatory | >11 = excessive daytime sleepiness; 11-14 = moderate and >15 = high | |||

| ESS (52) | P | yes | sleepiness | internal | convergent/discriminant | yes. cutoff score of 6 | |||||

| ESS-CHAD (53) | P | yes | sleepiness | structure | test-retest; internal | construct; criterion | |||||

| FoSI (54) | PA | quality | structure | internal | convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | |||||

| I SLEEPY (55) | N | quality, sleepiness | criterion | yes; those endorsing three or more symptoms or complaints on the questionnaires | |||||||

| IF SLEEPY (55) | N | quality, sleepiness | criterion | yes; those endorsing three or more symptoms or complaints on the questionnaires | |||||||

| I'M SLEEPY (55) | N | quality, sleepiness | criterion | yes; those endorsing three or more symptoms or complaints on the questionnaires | |||||||

| ISI (5) | P | quality | structure | test-retest; internal | criterion; convergent/discriminant | yes; a total score ≥9 | partially diagnostic criteria of insomnia in DSM-IV |

DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of insomnia by interview | |||

| ISI (56) | T (Swedish) | quality | internal | criterion | partially diagnostic criteria of insomnia in DSM-IV |

chronic pain | |||||

| ISI (57) | T (German) | quality | structure | internal | convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | partially diagnostic criteria of insomnia in DSM-IV |

||||

| JSQ (58) | P | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene | structure | internal | content | confirmatory | yes; 80 for total score | standardized T scores by age and gender; 50.00 ± 10.00 | |||

|

JSQ (preschool) (59) |

P | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene | structure | internal | face; criterion | yes; cutoff 84 | standardized T scores by age and gender; 50.00 ± 10.00 | ||||

| LSTCHQ (60) | N | quantity, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | test-retest | face; content; construct | |||||||

| MCTQ (61) | N | no, therefore added here | regularity | ||||||||

| MEQ (62) | T (Italian) | regularity, sleepiness | structure | internal | content | ||||||

| MEQ (63) | P | regularity, sleepiness | structure | internal | convergent/discriminant | ||||||

| aMEQ (64) | PT (European Portuguese) |

regularity, sleepiness | internal | face; content | mean ± 1SD, percentiles 10 and 90, and the less restrictive percentiles 20/80; cut-points for the males and females |

||||||

| aMEQ-R (65) | PA | regularity, sleepiness | internal | content; criterion; convergent/discriminant | aMEQ (≤45 and ≥60); aMEQ-R (≤23 and ≥33) | ||||||

| MESC (66) | P | yes | regularity, sleepiness | structure | internal | convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | ||||

| MESSi (67) | PT (Turkish) | regularity, sleepiness | structure | internal | face; content; convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | |||||

| MESSi (68) | P | regularity, sleepiness | internal | convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | ||||||

| My Sleep and I (69) | P | quantity, hygiene, ecology | structure | internal | convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | |||||

| My children's sleep (69) | P | quantity, hygiene, ecology | structure | internal | convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | |||||

| NARQoL-21 (70) | NT (English) | quality, sleepiness | structure | test-retest; internal; | content; construct; convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | yes; a NARQoL-21 score below 42 | diagnostic criteria for narcolepsy according to ICSD-3 |

|||

| NSD (71) | NA | quality | Asthma per Global Initiative for Asthma classification |

||||||||

| NSS (72) | AT (Chinese) |

sleepiness | structure | internal | face; content; convergent/discriminant | ICSD-3 criteria |

|||||

| OSA Screening Questionnaire (73) | N | quality | face; content | Down syndrome | |||||||

| OSA-18 Questionnaire (74) | T (Chinese) | quality | structure | test-retest; internal | construct; convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | yes; cutoff scores ranging from 55 to 66 | OSA per ICSD 2 | |||

| OSA-18 Questionnaire (75) | T (Chinese) | quality | test-retest; internal | construct; criterion | |||||||

| OSA-18 Questionnaire (76) | T (Dutch) | quality | test-retest; internal | convergent/discriminant | craniosynostosis | ||||||

| OSA-18 Questionnaire (77) | T (Greek) | quality | test-retest; internal | criterion | |||||||

| OSA-18 Questionnaire (78) | T (Portuguese) | quality | internal | convergent/discriminant | |||||||

| OSA-18 Questionnaire (79) | T (Spanish) | quality | structure | test-retest; internal; interrater/observer | construct; convergent/discriminant | ||||||

|

OSA-5 Questionnaire (short) (80) |

A | quality | structure | internal | content | confirmatory | |||||

| OSD-6 QoL Questionnaire (81) | T (Greek) | yes | quality | test-retest; internal | criterion | ||||||

| oSDB and AT (82) | N | quality, treatment | internal | face; content; construct; criterion | |||||||

| OSPQ (83) | N | quality, regularity, sleepiness | structure | test-retest; internal | face | confirmatory | the cutoffs for the 95th percentile (T-score of 70) by sex and age |

||||

| PADSS (84) | N | quality | structure | test-retest; internal | face; construct | yes; cutoff for the overall scale was located at 13/14 |

sleepwalking or sleep terror per ICSD | ||||

| PDSS (85) | T (Brazilian Portuguese) | quantity, regularity, sleepiness | test-retest; internal | content | |||||||

| PDSS (86) | T (Japanese) | quantity, regularity, sleepiness | structure | test-retest; internal | content | ||||||

| PDSS (87) | T (Turkish) | quantity, regularity, sleepiness | structure | internal | content; construct | confirmatory | |||||

| PDSS (88) | P | quantity, regularity, sleepiness | internal | construct | confirmatory | ||||||

| PDSS (89) | PAT (Russian) |

quantity, regularity, sleepiness | structure | test-retest; internal | face; content | confirmatory | |||||

| Pediatric Sleep CGIs (90) | N | quantity, hygiene, ecology | convergent/discriminant | elements of insomnia as defined by the ICSD |

Autism Spectrum Disorders |

||||||

| PedsQL(fatigue scale) (91) | AT (Arabic) | sleepiness | internal | content; construct; convergent/discriminant | cancer | ||||||

| PedsQL (fatigue scale) (92) | AT (Chinese) | sleepiness | structure | internal | content; construct; criterion | confirmatory | acute leukemia | ||||

| PedsQL(fatigue scale) (93) | PT (Brazilian Portuguese) | sleepiness | structure | internal | construct; convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | cancer | ||||

| PISI (94) | P | quality | structure | test-retest; internal | content; construct; convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | items per group consensus regarding the following ICSD-II general insomnia criteria |

||||

| PNSSS (95) | P | ecology | interrater | assess five of the AAP recommendations related to sleep practices | |||||||

| PosaST (96) | T (Brazilian Portuguese) | quality | internal | criterion | yes; using the cumulative score ≥2.72 of the original scale | ||||||

| PPPS (97) | P | quantity; regularity, sleepiness, hygiene | internal | ||||||||

| P-RLS-SS (98) | N | quality | face; content | including also ADHD subgroup per DSM-IV criteria |

|||||||

| PROMIS (99) | P | quality, regularity, sleepiness | internal | face; content | |||||||

| PROMIS (100) | P | quality, regularity, sleepiness | structure | content | confirmatory | ||||||

| PROMIS (101) | P | quality, regularity, sleepiness | structure | internal | content; construct | confirmatory | |||||

| PROMIS (102) | PA | quality, regularity, sleepiness | content | ||||||||

| PSIS (103) | P | quality, regularity | internal | content; construct | child psychopathology and functioning per DSM-IV-TR | ||||||

| PSQ (104) | P | quality | internal | obese adolescents undergoing bariatric surgery | |||||||

| PSQ (105) | T (Turkish) | quality | internal | content; construct | items similar DSM-IV | ||||||

| PSQ (106) | T (Spanish) | quality | structure | yes; cutoff score >0.33 | |||||||

| PSQ (107) | T (Malay) | quality | test-retest; internal | face; content | |||||||

| PSQ (108) | P | quality | criterion | yes; original 0.33 and AHI>1.5 | |||||||

| PSQ (109) | P | quality | face; content | yes; cutoff of 0.72–0.76. | asthma per ICD 9 | ||||||

| PSQ (110) | PT (Chinese) | quality | structure | test-retest | content; construct | ||||||

| PSQ (111) | T (Thai) | quality | test-retest; internal | face; content | yes; a cutoff of >0.33 | ||||||

| PSQ (112) | P | quality | yes; a cutoff value of seven points | ||||||||

| PSQ (113) | PT (Portuguese) | yes | quality | test-retest; internal | face; content | ||||||

| PSQ (114) | PT | yes | quantity, quality, regularity | structure | test-retest; internal | face; construct | confirmatory | ||||

| PSQI (115) | T (Brazilian Portuguese) | yes | quantity, quality, regularity | structure | test-retest; internal | content | confirmatory | ||||

| PSQI (116) | P | yes | quantity, quality, regularity | structure | internal | content; convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | ||||

| RLS (117) | NP | quality | test-retest; internal | face; content | calculated RLS index (difference in score between 14 day time points); one control subject had a higher index value (14) than two RLS-diagnosed (10 and 13) |

criteria for children established by the International Restless Legs Syndrome study group |

|||||

| SDIS (118) | P | yes | quantity, quality, sleepiness | convergent/discriminant | insomnia per ICSD-2 or ICSD-3 |

||||||

| SDPC (119) | P | quantity, quality, sleepiness | content | cancer | |||||||

| SDSC (120) | T (Chinese) | yes | quantity, quality, sleepiness | structure | internal | construct | confirmatory | original SDSC fits ASDC | |||

| SDSC (121) | T (French) | yes | quantity, quality, sleepiness | structure | test-retest; internal; interrater/observer | construct; convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | T-score >70 | original SDSC fits ASDC | ||

| SDSC (122) | T (Persian) | yes | quantity, quality, sleepiness | internal | construct; convergent/discriminant | original SDSC fits ASDC | |||||

| SDSC (14) | P | yes | quantity, quality, sleepiness | internal | construct; convergent/discriminant | original SDSC fits ASDC | Down syndrome | ||||

| SDSC (123) | P | yes | quantity, quality, sleepiness | internal | construct; convergent/discriminant | original SDSC fits ASDC | neurocritical care acquired brain injury | ||||

| SDSC (124) | P | yes | quantity, quality, sleepiness | confirmatory | ADHD | ||||||

| SDSC* (125) | N | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness | structure | internal | content | ICSD 2 as reference | |||||

| SHI (126) | T (Turkish) | quantity, quality, sleepiness | structure | test-retest; internal | construct | confirmatory | major depressive disorder per DSM-IV criteria |

||||

| SHIP (127) | N | quantity, regularity, sleepiness | internal | content; construct; criterion; convergent/discriminant | chronic headache per International Headache Classification | ||||||

| Sleep Bruxism (128) | N | quality | |||||||||

| SNAKE (129) | N | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene, ecology | structure | test-retest; internal | construct; convergent/discriminant |

confirmatory | T-score and percentage rank for raw score per factor | per ICSD-2 | severe psychomotor impairment | ||

| SQI (5) | P | quality | structure | internal | convergent/discriminant | yes; total score ≥5 | DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of insomnia by interview | ||||

|

SQ–SP

(130) |

P | yes | quantity, quality, sleepiness, | structure | test-retest; internal | construct; convergent/discriminant |

confirmatory | individuals with intellectual disability | |||

| SQS-SVQ (131) | AT (Turkish) | quantity, regularity, ecology | structure | test-retest; internal | criterion | confirmatory | sleep quality items comparable to DSM IV insomnia criteria | ||||

| SRSQ (132) | N | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness | test-retest; internal | content | yes; a cutoff of 17.3 | ||||||

| SSR (133) | T (Spanish) | quality, regularity, sleepiness | structure | internal | construct; convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | original items per ICSD | ||||

| SSR (43) | T (Portuguese) | quality, regularity, sleepiness | internal | content | original items per ICSD | ||||||

| SSSQ (134) | N | quantity, regularity | test-retest | criterion | |||||||

| STBUR (135) | N | quality | structure | yes; 10.40 (1.37–218.3) for 5 items | |||||||

| STQ (136) | P | quantity, regularity | convergent/discriminant | ||||||||

| The Children's Sleep Comic (137) | N | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene | content; construct | ICSD-2 | |||||||

| The Children's Sleep Comic (138) | P | quantity, quality, regularity, sleepiness, hygiene | internal | content; convergent/discriminant | yes; a total intensity of sleep problem score of 9 |

stanine value (5±2), percentile rank and relative frequency for the raw intensity of sleep problem score | ICSD-2 | ||||

| TuCASA (139) | AT (Portuguese) | yes | quality | internal | content; convergent/discriminant | ||||||

| YSIS (140) | NT (English) | quality | structure | test-retest; internal | face; content; construct; convergent/discriminant | confirmatory | yes: Normal ∶< 22 (< 70th percentile); Mild insomnia ∶ 22 (70th percentile)−25; Moderate insomnia/clinical insomnia ∶ 26 (85th percentile)−29; Severe insomnia/clinical insomnia ∶≥ 30 (95th percentile |

based on ICSD-3 [12] and DSM-V [13] diagnostic criteria |

Results

Studies Included

As described by Figure 1 , the total number of studies generated from the database search was sizeable, at n=341. Key emphasis of a pediatric diagnostic tools’ use, development or validation deemed it eligible for review, as well as the general translation and consequent adaptation of any pediatric questionnaire, survey, log, diary, etc. The titles and abstracts of each report were screened accordingly, resulting in the omission of 193 articles and final inclusion of 144 articles. Exported abstracts were then assigned their respective full-text. Complete text access was not available for 14, while retrieved from either the literature database “Library Genesis” or via author permission (n=4, see Acknowledgments), leaving 144 or 70 tools eligible for review based on the search conducted.

A more thorough examination of methodological processes was then executed to reveal categories to which each article was suitably assigned for ease of future assessment (refer to Table 1 ); “New Development (N),” “Psychometric Analysis (P),” and “Translation (T)/Adaptation (A),” or a combination thereof. Each paper was assigned to the appropriate criteria; “Development” if the report’s main purpose was to produce an unprecedented tool, “Psychometric Analysis” if the explicit objective was to assess the reliability and validity of said tool, and “Translation and/or Adaptation” for all studies that in any way translated or altered a tool to suit a specific population, culture, and/or nation. Overall ( Table 2 ), 36.8% of the studies aimed to merely psychometrically evaluate a pediatric sleep tool, while 9% additionally translated it. 24.3% of the studies aimed to independently translate while 4.2% additionally adapted their tool. As for lone adaptations, there were 4.2% of studies that performed this, while 18.8% created an entirely new tool. 1.4% of the studies conducted both a new tool development and translation and alike, 0.7% of studies adapted their new tool to particular population, culture, or other.

Study Characteristics

The structural organization and publication features of each study are detailed in Table 1 . In the Appendix are the acronyms for each tool reviewed. Since the 2011 Spruyt review on pediatric diagnostic and epidemiological tools, approximately 144 “tool”-studies have been published. The focus into pediatric tool evaluation peaked in 2014 where 16.7% of all studies were conducted, closely followed by 2017 (13.9%), and 2016 and 2019, each at 13.2% as well as 2015 at 12.5%. As for the remaining years of this decade, between 2010 and 2014, 2018 , the percentage of total studies published ranged from 0.7%–9.7% (n=1–10) per year. Over a third of the total studies were published in Europe (38.9%), followed by North America (25%), Asia (18.1%), Middle East (2.8%), South America (7.6%), Australia and Oceania (6.3%), and the United Kingdom (1.4%).

Across all 144 studies evaluated, it was evident that sleep tools were predominantly developed and evaluated for a combination of children and adolescents between the ages of 6–18 years (27.1%), followed closely by tools for adolescents 13–18 years at 22.2% and children 6–12 years alone at 16.7%. Only 10 studies covered the 0–18 years age range, and one did not define its range (82). Meanwhile, only 5.6% of all the studies assessed tools for preschool-aged children (2–5 years) alone and 1.4% for infants (0–23 months) alone. As for the studies remaining, a combination of age ranges was investigated with the most predominant combination being both preschool children and children (ages of 2–12 years) at 8.3% of the total studies. The lesser frequent combinations of age ranges for which tools were assessed in these studies, ranged from 0.7–7.6% per combination.

As for the sample size, this ranged between 20 and 11,626 children inclusive of adult (6–13) participants across all publications, where 15.6% of all studies used a sample size >1,000 participants large ( Table 2 ). Of these study samples, approximately 46.5% of respondents were parents, 41% were self-report, and 11.1% either a combination of experts, children, mothers, and parents. For two, the respondent is primarily a professional (17, 95).

Sleep Categories

As exemplified in Table 2 , the overall focus of these studies was overwhelmingly directed at tools measuring the quality of sleep or identification of sleep pathologies in all pediatric age classifications (68.1%), followed by the levels of sleepiness (55.6%) and duration of sleep (48.6%). Various secondary coobjectives of these studies were to investigate tools measuring the sleep regularity (46.5%) and sleep hygiene practices (29.2%). Rarely but in existence, was the singular assessment of sleep ecology and treatment around sleep pathologies at a frequency of 21.5% and 0.7%, respectively. About 19 studies (13.2%) queried simultaneously nearly all categories (except treatment).

The 11 Steps

Regarding the psychometric evaluation step-by-step guide proposed by Spruyt (2, 3), less than half the required 11 steps (chiefly 1, 2, 6, 8, and 9 were done) were fulfilled across all studies. Steps 3 and 10 were often not reported (i.e., 84.7% and 63.2%, respectively). Three studies reported all steps (2.1%), three only lack step 11 (2.1%), and four (2.8%) only lack steps 10 and 11. The most common combination of steps (7.7%) reported are 1, 2, and 4 joined with 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 or 5, 6, 8, 9 or 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. After a decade, only 18 papers (12.5%) reported some form of norms. An in-depth description of the steps fulfilled is described in the categorically-divided (per purpose, see Methods) results below.

Tools Newly Developed

According to our search criteria, a total of 27 novel pediatric sleep tools were developed between 2010 and 2020 (refer to Table 2 and shaded). Of these, approximately eight were published in Europe (29.6%), eight in North America (29.6%), four in Asia (14.8%), three in South America (11.1%), two in Australia and Oceania (7.4%), and two in the United Kingdom (7.4%). The majority were developed for child-adolescent age ranges (66.7%), while one for preschool children (2–5 years) and one for all three aforementioned ages (2–18 years). All newly developed tools possessed a multipurpose objective, most of which assessed sleep quality (77.8%), followed by the assessment of sleepiness (51.9%) and sleep regularity (41.7%) and sleep quantity (41.7%), while more rarely assessing hygiene (25%), ecology (12.5%), and treatment (4.2%).

In addition, three tools being newly created are an English translation of the NARQoL-21 (70) and YSIS (140), and also an adaptation, the nighttime sleep diary (NSD) (71). The latter being a diary adapted to monitor nighttime fluctuations in young children with asthma.

Only two tools were developed according to the 11 aforementioned steps required for psychometric validation of a tool; the NARQoL-21 (70) and SNAKE (129) (refer to Table 2 ). One other tool, OSPQ (83) also developed normative scores for widespread usage while fulfilling most steps but steps 3 and 9. Whereas the CSAQ (27) fulfilled all steps except step 11, and the BRIAN-K (16), PADSS (84), and SDSC* (125) except steps 10 and 11. The outstanding tools were mostly absent of steps 5, 7, 8, 9, and 10. For the newly developed diary, NSD (71) steps 1–6 were fulfilled.

Almost half of the tools queried general sleep problems (41.7%). Twenty-five percent aimed at surveying sleep disordered breathing. While others such as sleep bruxism (128), PADSS (84), P-RLS-SS (98), RLS (117), NARQoL-21(70), YSIS (140), and NSD (71) focused on a specific sleep problem (16.7%). Tools aimed at investigating sleep complaints in children with (developmental) disabilities are besides NSD (71), the OSA Screening Questionnaire (73), Pediatric Sleep CGIs (90), SHIP (127), and SNAKE (129).

Tools Translated

In total, 35 out of the total 144 studies primarily aimed to translate an existing tool alone (refer to Table 2 ). Namely, 17 tools have been translated: BISQ (15), CCTQ (19), CSHQ (29, 33, 34, 40–43), CSM (45), CSRQ (46), DBAS (49), ISI (56, 57), MEQ (62), OSA-18 (74–79), OSD-6 (81), PDSS (85–87), PosaST (96), PSQ (105–107, 110, 111, 113), PSQI (115), SDSC (120–122), SHI (126), and SSR (43, 133). The most frequently translated tools were: OSA-18 (17.1%), CSHQ (14.3%), and PSQ (11.4%). The most common translation was to Portuguese (n=4), Spanish (n=4), and Turkish (n=4), followed by Brazilian Portuguese (n=3), Chinese (n=3), and Dutch (n=3). Less often, tools were translated to German, Persian, and Greek as well as English, Italian, Polish, Swedish, Japanese, French, Malay, and Thai. Again, primarily tools for child/adolescent age ranges as parental reports have been translated. Of these, the main categorical foci, and often overlapping, were sleep quality (77.1%), quantity (48.6%), and sleepiness (48.6%).

When ranked from most to least prevalent step, apart from steps 1 and 2, we found: step 8 (97.1%), step 4 (91.4%), step 9 (88.6%), step 6 (85.7%), step 5 (57.1%), step 7 (51.4%), and step 10 (34.3%) being performed across the studies. The CSHQ (34) and SDSC (120, 121) included norm development (step 11). Step 3 is missing in all translations. Only the translation of the SDSC fulfilled nearly all steps with (121) missing step 3 and (120) missing steps 3 and 9. Receiver Operator Curve (ROC) analyses were performed in five : OSA-15 (74), PosaST (96), PSQ (106, 111), and CSHQ (43).

Tools Adapted

Moreover, six studies (see Table 2 ) specifically aimed to adapt a tool from a preexisting one, most notably the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) (66.7%), among these a shortened version and infant adaptation, along with the BEDS (14) (16.7%) adapted toward children with Down syndrome, and the OSA-18 Questionnaire (16.7%), which was also shortened [toward OSA-5 (80)] to suit the sample of interest. Although the number of items may have changed, no substantial changes to the answer categories could be noted. Only 33.3% reported steps 3, 4, 5, 7, 10 yet steps 6, 8, 9 were analyzed in 83.3%. None developed norms. In two studies (38, 44) ROC analyses were pursued for the CSHQ.

Tools Adapted and Translated

Six studies adapted and also translated existing tools (see Table 2 ): CSHQ (29), PedsQL (91, 92), SQS-SVQ (131), TuCASA (139), and NSS (72). The CSQH and TuCASA were adapted and translated to Portuguese, the PedsQL to Arabic and Chinese, while SQS-SVQ to Turkish and NSS to Chinese. The adaptations involved an infant version of CSHQ and child-sample for NSS, the PedsQL to children with cancer and acute leukemia, and the TuCasa was adapted toward children of low socioeconomic status. Regarding the SQS-SVQ it was modified based on personal communication with the authors of the original version. That is, four items were added.