Abstract

miR-532-3p is a widely documented microRNA (miRNA) involved in multifaceted processes of cancer tumorigenesis and metastasis. However, the clinical significance and biological functions of miR-532-3p in bone metastasis of prostate cancer (PCa) remain largely unknown. Herein, we report that miR-532-3p was downregulated in PCa tissues with bone metastasis, and downexpression of miR-532-3p was significantly associated with Gleason grade and serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels and predicted poor bone metastasis-free survival in PCa patients. Upregulating miR-532-3p inhibited invasion and migration abilities of PCa cells in vitro, while silencing miR-532-3p yielded an opposite effect on invasion and migration abilities of PCa cells. Importantly, upregulating miR-532-3p repressed bone metastasis of PCa cells in vivo. Our results further demonstrated that overexpression of miR-532-3p inhibited activation of nuclear facto κB (NF-κB) signaling via simultaneously targeting tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 1 (TRAF1), TRAF2, and TRAF4, which further promoted invasion, migration, and bone metastasis of PCa cells. Therefore, our findings reveal a novel mechanism contributing to the sustained activity of NF-κB signaling underlying the bone metastasis of PCa.

Keywords: miR-532-3p, bone metastasis, NF-κB signaling, prostate cancer

In this study, we report that miR-532-3p was downregulated in PCa tissues with bone metastasis, and downexpression of miR-532-3p was significantly associated with Gleason grade and serum PSA levels, and it predicted poor bone metastasis-free survival in PCa patients.

Introduction

Metastasis to bone is a principal characteristics of prostate cancer (PCa),1 which contributes to poor quality of life and survival time in PCa patients.2 Thus, exploring the signaling networks underlying this clinical phenomenon is crucial to facilitate the development of a novel anti-bone metastasis therapeutic strategy in PCa.

The nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway is a pivotal signaling molecule implicated in bone metastasis in several cancer types, such as PCa3 and breast cancer.4 Since its discovery,5 several studies have documented that NF-κB signaling plays an important role in inflammation and immunity.6,7 By binding their respective ligands, the receptors recruit different receptor-associated proteins, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factors (TRAFs), and induce the K-63 polyubiquitination of receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1) as a ubiquitin ligase, which leads to activation of the TAK1/TAB2/3 complex. Finally, nuclear translocation of NF-κB is dramatically enhanced when the activated TAK1/TAB2/3 complex phosphorylates the inhibitor of NF-κB kinase (IKK)-α/β/γ complex.8,9 Constitutive activation of NF-κB signaling has been extensively identified and involved in the development and progression in a variety of cancers.6,10, 11, 12 Accumulating studies have shown that activity of NF-κB signaling significantly contributes to the bone metastasis of various types of cancers13,14 via promoting the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), invasiveness, and survival of cancer cells.15, 16, 17 Therefore, it is of great necessity to uncover the underlying mechanism responsible for constitutive activation of NF-κB signaling in the bone metastasis of PCa.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of endogenous non-coding RNAs, and they post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression via interacting with the 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) of downstream target genes.18 miRNAs exert their functions in several biological processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and cardiogenesis.18,19 Moreover, aberrant expression of miRNAs has been widely reported to be implicated in progression and metastasis in several types of cancer,20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 including bone metastasis of cancers.3,27,28 miR-532-3p, one of the originally discovered miRNAs, has been reported to play a paradoxical role in different types of cancer that is dependent on cellular context or functional relevance. A study from Subat et al.29 has reported that upregulation of miR-532-3p driven by epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation promoted the progression of lung adenocarcinoma; conversely, miR-532-3p expression was reported to be reduced in gastric cancer30 and Hodgkin’s lymphoma.31 However, the clinical significance and functional role of miR-532-3p in bone metastasis of PCa have not yet been investigated.

In the current study, our results revealed that miR-532-3p was dramatically downregulated in PCa tissues with bone metastasis compared with that in PCa tissues without bone metastasis, which was positively associated with Gleason grades and serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels and predicted poor bone metastasis-free survival in PCa patients. Upregulating miR-532-3p inhibited, whereas silencing miR-532-3p enhanced, invasion and migration of PCa cells in vitro, and, importantly, upregulating miR-532-3p repressed bone metastasis of PCa cells in vivo. Our results further showed that miR-532-3p inhibited invasion and migration abilities of PCa cells by inactivating NF-κB signaling via targeting TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4. Collectively, our results reveal a novel mechanism contributing to activation of NF-κB signaling in bone metastasis of PCa, supporting the evidence that miR-532-3p functions as a tumor suppressor in bone metastasis of PCa.

Results

miR-532-3p is Downregulated in PCa Tissues with Bone Metastasis

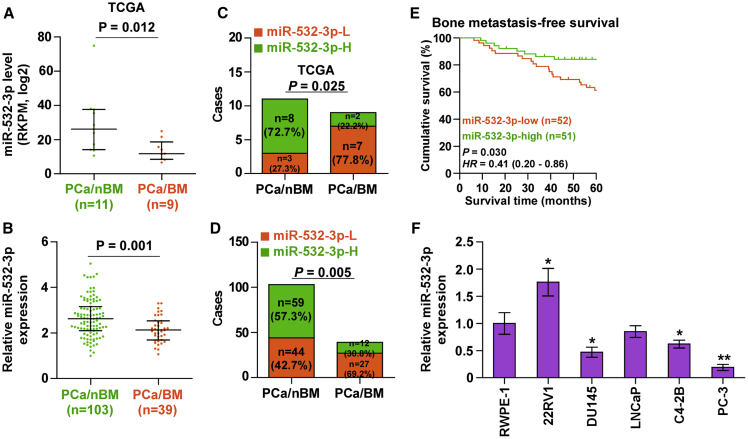

To first investigate the expression level of miR-532-3p in PCa tissues with bone metastasis (PCa/BM) and PCa tissues without bone metastasis (PCa/nBM), we further analyzed the miRNA sequencing dataset of PCa from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). As shown in Figure 1A, we found that miR-532-3p was downregulated in PCa/BM (n = 9) compared with that in PCa/nBM (n = 11). The expression levels of miR-532-3p in a larger group of PCa tissues were further examined. Consistent with the result from TCGA, miR-532-3p expression was dramatically reduced in PCa/BM compared with that in PCa/nBM (Figure 1B). Furthermore, the percentage of low levels of miR-532-3p was higher in PCa/BM than that in PCa/nBM in TCGA and in our results (Figures 1C and 1D). The statistical analysis of miR-532-3p expression with clinicopathological characteristics in PCa patients revealed that downexpression of miR-532-3p was positively correlated with serum PSA levels, Gleason grade, and bone metastasis status in PCa patients (Table 1), and, more importantly, downexpression of miR-532-3p predicted shorter bone metastasis-free survival in PCa patients (Figure 1E). miR-532-3p expression was further measured in normal prostate epithelial cells (RWPE-1) and five PCa cell lines, including primary PCa cells (22RV1), brain metastatic PCa cells (DU145), lymph node metastatic PCa (LNCaP) cells, and two bone metastatic PCa cells (C4-2B and PC-3). As shown in Figure 1F, we found that compared with that in RWPE-1 cells, miR-532-3p expression was elevated in 22RV1 cells, but differentially reduced in metastatic PCa cell lines, particularly in bone metastatic PCa cells (PC-3). Collectively, these results indicated that downexpression of miR-532-3p may be implicated in the bone metastasis of PCa.

Figure 1.

miR-532-3p Is Downregulated in PCa Tissues with Bone Metastasis

(A) miR-532-3p expression levels in 9 PCa tissues with bone metastasis (PCa/BM) and 11 PCa tissues without bone metastasis (PCa/nBM) as assessed by analyzing the TCGA PCa miRNA sequencing dataset. (B) Real-time PCR analysis of miR-532-3p expression in 103 PCa/nBM and 39 PCa/BM samples. Transcript levels were normalized to U6 expression. ∗p < 0.05. (C and D) Percentages and number of samples showed high or low miR-532-3p expression in our (C) and TCGA (D) PCa samples. p < 0.001. (E) Kaplan-Meier analysis of bone metastasis-free survival curves of the PCa patients stratified by miR-532-3p expression. (F) Real-time PCR analysis of miR-532-3p expression levels in the indicated cell lines. Transcript levels were normalized to U6 expression. ∗p < 0.05.

Table 1.

The Relationship between miR-532-3p and Clinicopathological Characteristics in 142 Patients with Prostate Cancer

| Parameters | No. of Cases | miR-532-3p Expression |

p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | |||

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤71 | 72 | 37 | 35 | 0.737 |

| >71 | 70 | 34 | 36 | |

| Differentiation | ||||

| Well/moderate | 65 | 31 | 34 | 0.613 |

| Poor | 77 | 40 | 37 | |

| Serum PSA | ||||

| <23.6 | 66 | 32 | 34 | |

| >23.6 | 76 | 39 | 37 | 0.043∗ |

| Gleason grade | ||||

| ≤7 | 81 | 31 | 50 | |

| >7 | 61 | 40 | 21 | <0.001∗ |

| BM status | ||||

| BM-free | 103 | 44 | 59 | |

| BM | 39 | 27 | 12 | 0.005∗ |

PSA, prostate-specific antigen; BM, bone metastasis. ∗p < 0.05.

Upregulating miR-532-3p Represses Bone Metastasis of PCa In Vivo

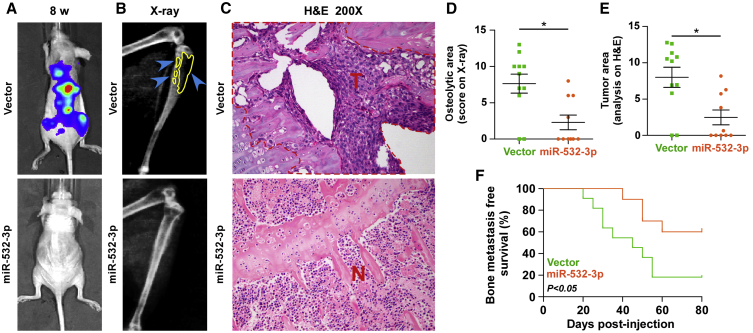

The abovementioned results implied that downexpression of miR-532-3p contributes to the bone metastasis of PCa. Therefore, the effect of miR-532-3p on the bone metastasis of PCa in vivo was further investigated in a mouse model of bone metastasis, where the luciferase-labeled vector or miR-532-3p-stably overexpressing PC-3 cells were inoculated respectively into the left cardiac ventricle of male nude mice to monitor the progression of bone metastasis by bioluminescence imaging (BLI) and X-ray (Figure S1A). As shown in Figures 2A–2C, upregulating miR-532-3p dramatically inhibited bone metastasis ability of PC-3 cells in vivo compared with the control group by BLI and X-ray, as well as reduced the tumor burden in bone via H&E staining of the tumor sections from the tibias of injected mice. Moreover, overexpression of miR-532-3p reduced bone metastatic scores and the osteolytic area of metastatic tumors, but it prolonged bone metastasis-free survival compared with the vector group (Figures 2D–2F). These findings indicated that upregulating miR-532-3p represses the bone metastasis of PCa in vivo.

Figure 2.

Upregulating miR-532-3p Represses Bone Metastasis of PC-3 Cells In Vivo

(A) Representative BLI signal of bone metastasis of a mouse from the indicated groups of mice at week 8. (B) Representative radiographic images of bone metastases in the indicated mice (blue arrows indicate osteolytic lesions). (C) Representative H&E-stained sections of tibias from the indicated mouse (T, tumor; N, the adjacent non-tumor tissues). (D) The sum of bone metastasis scores for each mouse in tumor-bearing mice inoculated with vector or miR-532-3p-overexpressing cells. (E) Histomorphometric analysis of bone osteolytic areas in the tibia of the indicated groups. ∗p < 0.05. (F) Kaplan-Meier analysis of mouse bone metastasis-free survival in the vector and miR-532-3p-overexpression groups.

Upregulating miR-532-3p Inhibits Migration, Invasion, and Proliferation

To determine the functional role of miR-532-3p in bone metastasis of PCa, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) based on miRNA expression data from TCGA was also performed. As shown in Figure 3A, low expression of miR-532-3p was significantly correlated with metastatic propensity. We further exogenously overexpressed miR-532-3p and endogenously silenced miR-532-3p via viral transduction in another bone metastatic PCa cell line (C4-2B) that expressed medium levels of miR-532-3p (Figure S1B). Invasion and migration assays were further carried out, and the results showed that upregulating miR-532-3p inhibited the invasion and migration abilities of PCa cells (Figures 3B and 3C); however, silencing miR-532-3p dramatically enhanced the invasion and migration abilities of PCa cells (Figure 3C). Moreover, upregulating miR-532-3p inhibited, whereas silencing miR-532-3p promoted, proliferation in PCa cells via colony formation and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dimethyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays (Figures 3D and 3E). The effects of miR-532-3p on the expression levels of anti-apoptotic proteins BCL2 and BCL2L1 were further examined in PCa cells. As shown in Figure 3F, upregulating miR-532-3p reduced BCL2 and BCL2L1 expression in PCa cells; conversely, silencing miR-532-3p increased expression levels of BCL2 and BCL2L1 in C4-2B cells. Taken together, these results demonstrated that overexpression of miR-532-3p suppresses invasion, migration, and proliferation as well as promotes anti-apoptotic ability in PCa cells in vitro.

Figure 3.

Upregulating miR-532-3p Inhibits Invasion and Migration in PCa Cells In Vitro

(A) GSEA revealed that low expression of miR-532-3p expression was significantly correlated with metastatic propensity. (B) Overexpression of miR-532-3p reduced invasion and migration abilities in PC-3 cells. ∗p < 0.05. (C) Overexpression of miR-532-3p reduced, whereas silencing miR-532-3p enhanced, invasion and migration abilities in C4-2B cells. ∗p < 0.05. (D) Overexpression of miR-532-3p reduced, whereas silencing miR-532-3p enhanced, colony formation abilities in PCa cells. ∗p < 0.05. (E) The effect of miR-532-3p on proliferation of PCa cells was assessed by an MTT assay. ∗p < 0.05. (F) The effect of miR-532-3p on expression of anti-apoptotic proteins, BCL2 and BCL2L1, was assessed by western blot. α-Tubulin served as the loading control.

miR-532-3p Targets TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4

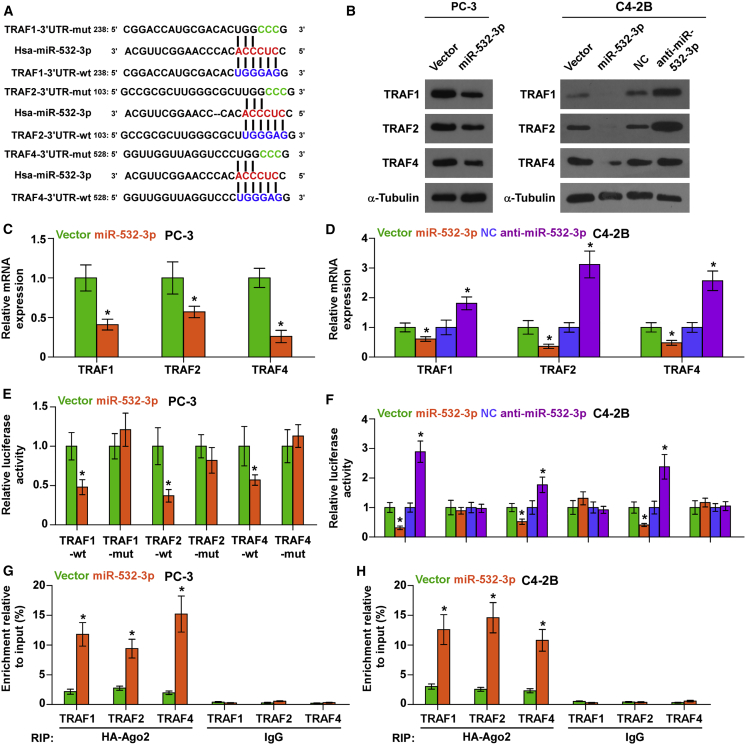

Through analyzing several publicly available algorithms, we found that multiple TRAF members, including TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4, may be potential targets of miR-532-3p (Figure 4A). Real-time PCR and western blotting analysis showed that overexpression of miR-532-3p reduced, whereas silencing miR-532-3p increased, the messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein expression of TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4 (Figures 4B–4D). Furthermore, upregulating miR-532-3p reduced, whereas silencing miR-532-3p elevated, the luciferase reporter activity of wild-type 3′ UTRs of TRAF1, TRAF2 and TRAF4, but had no effect on the mutant 3′ UTR of TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4 in PCa cells (Figures 4E and 4F). In addition, a direct association of miR-532-3p with TRAF1, TRAF2 and TRAF4 transcripts was demonstrated via a micro-ribonucleoprotein (miRNP) immunoprecipitation (IP) assay (Figures 4G and 4H). Taken together, our results demonstrated that TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4 are direct targets of miR-532-3p.

Figure 4.

miR-532-3p Targets TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4

(A) Predicted miR-532-3p targeting sequence and mutant sequences in 3′ UTRs of TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4. (B) Western blotting of TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4 expression in the indicated cells. α-Tubulin served as the loading control. (C and D) Real-time PCR analysis of TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4 expression in the indicated PC-3 (C) and C4-2B (D) cells. ∗p < 0.05. (E and F) Luciferase assay of cells transfected with pmirGLO-3′ UTR reporter of TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4 in the indicated PC-3 (E) and C4-2B (F) cells. ∗p < 0.05. (G and H) miRNP IP assay showing the association between miR-532-3p and TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4 transcripts in the indicated PC-3 (G) and C4-2B (H) cells. Pulldown of IgG antibody served as the negative control.

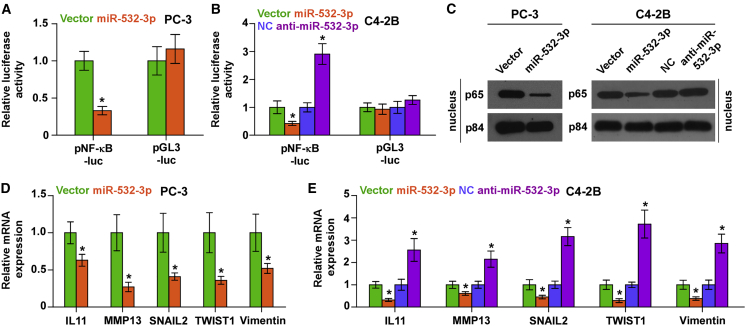

Upregulating miR-532-3p Inhibits the NF-κB Signaling Pathway in PCa Cells

As an adaptor protein of NF-κB signaling, the TRAF protein family mediates TNF-induced activation of NF-κB signaling.8,9 Thus, we further investigated the effect of miR-532-3p on NF-κB signaling. A luciferase reporter assay showed that overexpression of miR-532-3p reduced, whereas silencing miR-532-3p enhanced, NF-κB-dependent luciferase activity in PCa cells (Figures 5A and 5B). Moreover, overexpression of miR-532-3p decreased, whereas silencing miR-532-3p increased, nuclear accumulation of NF-κB/p65 via cellular fractionation and western blotting analysis (Figure 5C). Real-time PCR analysis demonstrated that upregulating miR-532-3p differentially repressed expression of multiple NF-κB signaling downstream metastasis-related target genes, including IL11, MMP13, SNAIL2, TWIST1, and Vimentin (Figures 5D and 5E). Conversely, silencing miR-532-3p increased expression levels of these targeted genes in PCa cells (Figure 5E). These results indicated that upregulating miR-532-3p inhibits NF-κB signaling in PCa cells.

Figure 5.

Upregulating miR-532-3p Inhibits NF-κB Signaling Activity

(A and B) NF-κB transcriptional activity was assessed by luciferase reporter constructs in the indicated PC-3 (A) and C4-2B (B) cells. ∗p < 0.05. (C) Western blotting of nuclear NF-κB/p65 expression. The nuclear protein p84 was used as the nuclear protein marker. (D and E) Real-time PCR analysis of Vimentin, SNAIL2, TWIST1, MMP13, and IL11 in the indicated PC-3 (D) and C4-2B (E) cells. Transcript levels were normalized to U6 expression. ∗p < 0.05.

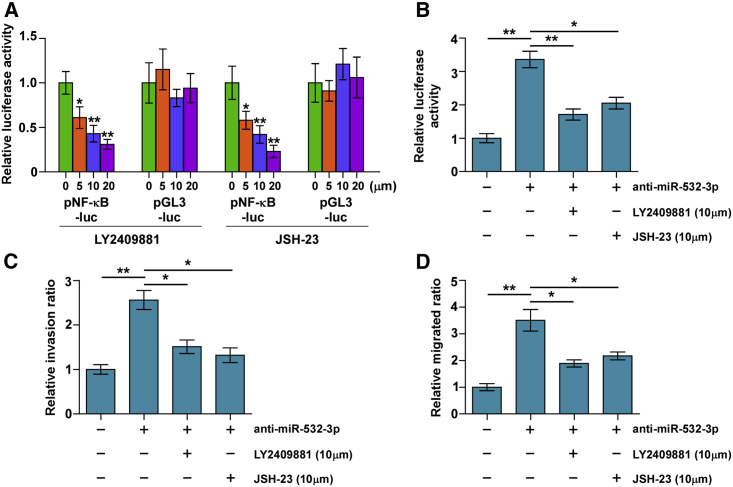

Silencing miR-532-3p Promotes Invasion and Migration via NF-κB Signaling

To determine the invasion and migration-stimulatory roles of silencing miR-532-3p in PCa cells via activating NF-κB signaling, NF-κB signaling inhibitors JSH-23 and LY2409881 were used in miR-532-3p-silenced C4-2B cells. First, both LY2409881 and JSH-23 showed gradient inhibition of the NF-κB reporter activity in a dose-dependent manner inC4-2B cells (Figure 6A). Importantly, JSH-23 and LY2409881 further reduced NF-κB-dependent luciferase activity in miR-532-3p-silenced C4-2B cells (Figure 6B). Furthermore, the stimulatory effects of miR-532-3p downexpression on migration and invasion in C4-2B cells were impaired by LY2409881 and JSH-23 (Figures 6C and 6D). Therefore, these results indicated that NF-κB signaling activation is essential for the pro-metastasis role of miR-532-3p downregulation in PCa cells.

Figure 6.

Activity of NF-κB Signaling Is Essential for Pro-invasiveness of miR-532-3p Downregulation in PCa Cells

(A) NF-κB signaling inhibitors LY2409881 and JSH-23 inhibited the NF-κB transcriptional activity in a dose-dependent manner in the indicated cells. Error bars represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05. (B) NF-κB signaling inhibitors LY2409881 (10 μM) and JSH-23 (10 μM) attenuated the stimulatory effect of miR-532-3p downregulation on NF-κB transcriptional activity in the indicated cells, respectively. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01. (C) LY2409881 and JSH-23 attenuated the stimulatory effect of miR-532-3p downregulation on invasion ability in the indicated cells, respectively. (D) LY2409881 and JSH-23 attenuated the stimulatory effect of miR-532-3p downregulation on migration ability in the indicated cells, respectively. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

Discussion

In the current study, our results found that miR-532-3p expression was reduced in PCa tissues with bone metastasis, which was positively correlated with Gleason grade and serum PSA levels and exhibited shorter bone metastasis-free survival in PCa patients. Our results further revealed that upregulating miR-532-3p repressed bone metastasis of PCa via inhibiting NF-κB signaling via directly targeting TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4. Therefore, our results elucidate the tumor-suppressive role of miR-532-3p in bone metastasis of PCa.

Numerous studies have reported that miR-532-3p expression was reduced in gastric cancer,30 metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma,32 and Hodgkin’s lymphoma,31 and downexpression of miR-532-3p was implicated in cancer tumorigenesis and metastasis via varying mechanisms.30, 31, 32 In contrast, miR-532-3p has been identified to be upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma,33 lung adenocarcinoma,29 and esophageal cancer.34 These findings suggested that the pro-cancer and anti-cancer roles of miR-532-3p are dependent on tumor type. It is noteworthy that miR-532-3p was reported to be dramatically downregulated in metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma, which was positively associated with metastatic progression in hepatocellular carcinoma.32 This finding implied that low levels of miR-532-3p may be significantly correlated with metastatic phenotypes of cancer. Consistently, our results further demonstrated that miR-532-3p expression was reduced in PCa tissues with bone metastasis, and low expression of miR-532-3p predicted poor bone metastasis-free survival in PCa patients. A gain-of-function assay showed that upregulating miR-532-3p reduced invasion and migration abilities of PCa cells in vitro, as well as repressed bone metastasis of PCa cells in vivo. Our results further revealed that miR-532-3p inhibited bone metastasis of PCa via inactivating NF-κB signaling. Collectively, our results determined the tumor-suppressive role of miR-532-3p in bone metastasis of PCa.

Constitutive activation of NF-κB signaling has been observed in multiple human cancer types.35, 36, 37 Furthermore, accumulating evidence has shown that activity of NF-κB signaling is essential for the bone metastasis of cancers.13,14 An important target of NF-κB signaling, granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), constitutively sustained NF-κB activity in breast cancer cells, which further facilitated the development of osteolytic bone metastasis.4 Furthermore, activity of NF-κB signaling was also reported to be crucial for the metastasis of PCa cells to bone.14 However, the specific mechanism of the constitutive activation of NF-κB signaling underlying the bone metastasis of PCa remains to be further clarified. In this study, we report that upregulating miR-532-3p inhibited activity of NF-κB signaling through directly targeting TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4 in PCa cells, resulting in the repression of bone metastasis of PCa in vivo and invasion and migration abilities of PCa cells in vitro. Our results further demonstrated that inhibition of NF-κB signaling by JSH-23 and LY2409881 reversed the pro-metastatic role of silencing miR-532-3p upon invasion and migration of PCa cells. Therefore, our results reveal a novel mechanism by which miR-532-3p inhibits NF-κB signaling in bone metastatic PCa cells.

Ubiquitination- and phosphorylation-mediated signaling transduction are critical regulatory mechanisms responsible for activation of NF-κB signaling,8,38 where TRAF proteins play important roles in TNF-induced activation of NF-κB signaling as an ubiquitin ligase.8,9 Several lines of evidence have reported that dysregulation of TRAFs contributes to cancer metastasis and progression via activating NF-κB signaling. Wang et al.39 have reported that TBC1D3-activated NF-κB signaling is dependent on the elevated transcription of TRAF1, which promoted migration of breast cancer cells. In addition, overexpression of TRAF2 due to amplification or rearrangement in 15% of human epithelial cancer constitutively activated NF-κB signaling.40 TRAF4 has been reported to promote the proliferation of anti-apoptosis of breast cancer cells by activating NF-κB signaling,41 and downregulating TRAF4 repressed proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of breast cancer cells via inhibiting NF-κB signaling.42 However, how these TRAFs proteins are simultaneously disrupted in the context of cancer remains undefined. In this study, our results demonstrated that several TRAF proteins, including TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4, were concomitantly targeted by miR-532-3p, which inhibited NF-κB signaling and repressed the bone metastasis of PCa. Thus, our findings reveal a plausible mechanism responsible for the anti-bone metastatic role of miR-532-3p in PCa, further supporting the critical role of NF-κB signaling in the bone metastasis of PCa.

In summary, our results demonstrate that regulation of miR-532-3p inactivates the NF-κB signaling pathway via targeting TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4, which finally represses bone metastasis of PCa. Therefore, a better understanding of the specific function and the underlying mechanism of miR-532-3p in the bone metastasis of PCa will facilitate the development of a potential anti-bone metastasis therapeutic avenue in PCa.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

The normal prostate epithelial cells (RWPE-1) and the human PCa cell lines 22RV1, LNCaP, PC-3, and C4-2B were obtained from Shanghai Chinese Academy of Sciences cell bank (China). RWPE-1 cells were grown in defined keratinocyte serum-free medium (SFM) (1×) (Invitrogen). All PCa cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Life Technologies) and cultured under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C.

RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription, and Real-Time PCR

Total RNA from tissues or cells was extracted using an RNA Isolation Kit (QIAGEN, USA). mRNA and miRNA were reverse transcribed from total mRNA using the RevertAid first-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was amplified and quantified on the CFX96 system (Bio-Rad, USA) using iQ SYBR Green (Bio-Rad, USA). The sequences of primers are provided in Table 2. Real-time PCR was performed as described previously.43 Primers for U6 and miR-532-3p were synthesized and purified by RiboBio (Guangzhou, China). U6 or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as the endogenous controls. Relative fold expressions were calculated with the comparative threshold cycle (2−ΔΔCt) method.

Table 2.

Primers Used in the Reactions for Real-Time RT-PCR

| Real-Time PCR Primer | 5′→3′ |

|---|---|

| TRAF1-forward | CTTCCCTTGAAGGAGCAGC |

| TRAF1-reverse | CTATAAGCCCAGGAAGCCG |

| TRAF2-forward | GCTCATGCTGACCGAATGTC |

| TRAF2-reverse | GCCGTCACAAGTTAAGGGGAA |

| TRAF4-forward | CAGGAGAGTGTCTACTGTGAGA |

| TRAF4-reverse | CCACACCACATTGGTTGGG |

| MMP13-forward | AACATCCAAAAACGCCAGAC |

| MMP13-reverse | GGAAGTTCTGGCCAAAATGA |

| TWIST1-forward | TCCATTTTCTCCTTCTCTGGAA |

| TWIST1-reverse | GTCCGCGTCCCACTAGC |

| SNAIL2-forward | TGACCTGTCTGCAAATGCTC |

| SNAIL2-reverse | CAGACCCTGGTTGCTTCAA |

| Vimentin-forward | ATTCCACTTTGCGTTCAAGG |

| Vimentin-reverse | CTTCAGAGAGAGGAAGCCGA |

| IL11-forward | TGAAGACTCGGCTGTGACC |

| IL11-reverse | CCTCACGGAAGGACTGTCTC |

| GAPDH-forward | ATTCCACCCATGGCAAATTC |

| GAPDH-reverse | TGGGATTTCCATTGATGACAAG |

Plasmid, Small Interfering RNA (siRNA), and Transfection

The human miR-532-3p gene was PCR amplified from genomic DNA and cloned into a pMSCV-puro retroviral vector (Clontech, Japan). The 3′ UTR regions of human TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4 were PCR amplified from genomic DNA and cloned into pmirGLO vectors (Promega, USA). The control plasmids and pNFκB-luc (Clontech, Japan) were applied to quantitatively examine the activity of transcription factors. Anti-miR-532-3p was purchased from RiboBio. Transfection of miRNA, siRNAs, and plasmids was performed as previously described.44

Western Blotting

Nuclear/cytoplasmic fractionation was accomplished with a cell fractionation kit (Cell Signaling Technology, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and whole-cell lysates were extracted with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Cell Signaling Technology). Western blotting was performed as previously described.45 Antibodies against TRAF1, TRAF2, TRAF4, BCL2 and BCL2L1 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, p65 was from Proteintech, and p84 was from Invitrogen. The membranes were stripped and reprobed with an anti-α-tubulin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) as the loading control.

Luciferase Assay

The luciferase reporter assay was performed as previously described.46 Cells were transfected with pmirGLO-TRAF1-3′ UTR, pmirGLO-TRAF2-3′ UTR, or pmirGLO-TRAF4-3′ UTR luciferase plasmid, 100 ng of the pNFκB reporter plasmid, plus 5 ng of pRL-TK, the Renilla plasmid (Promega), using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Luciferase and Renilla signals were measured 36 h after transfection using a Dual-Luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

miRNA IP

Cells were co-transfected with HA-Ago2, followed by HA-Ago2 IP using anti-HA-antibody. Real-time PCR analysis of the IP material was performed to test the association of the mRNAs of TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF4 with the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC).

Invasion and Migration Assays

The invasion and migration assays were performed using a Transwell chamber consisting of 8-mm membrane filter inserts (Corning Life Sciences) with or without coated Matrigel (BD Biosciences), respectively, as previously described.47 Briefly, the cells were trypsinized and suspended in serum-free medium. Then, 1.5 × 105 cells were added to the upper chamber, and the lower chamber was filled with the culture medium supplemented with 10% FBS. After incubation for 24–48 h, cells were passed through the coated membrane to the lower surface, where they were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with hematoxylin. The cell count was performed under a microscope (×100).

MTT Assay

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates in triplicate at the initial density of 0.2 × 104 cells/well. At various time points, groups of cells were incubated with 100 μL of 0.5 mg/mL sterile MTT (Sigma) for 4 h at 37°C. The culture medium was then removed, and 150 μL of DMSO (Sigma) was added. The absorbance values were measured at 570 nm, using 655 nm as the reference wavelength.

Colony Formation Assays

Cells were plated in six-well plates (0.5 × 103 cells/plate), cultured for 7 days, fixed with 10% formaldehyde for 5 min, and stained with 1% crystal violet for 30 s prior to quantification of the number of colonies.

Animal Study

For the bone metastasis study, BALB/c-nu mice (5–6 weeks old, 18–20 g) were anesthetized and inoculated into the left cardiac ventricle with 1 × 105 PC-3 cells in 100 μL of PBS. Bone metastases were monitored by BLI as previously described.48 Osteolytic lesions were identified on radiographs as radiolucent lesions in the bone. The area of the osteolytic lesions was measured using the MetaMorph image analysis system and software (Universal Imaging), and the total extent of bone destruction per animal was expressed in square millimeters. Each bone metastasis was scored based on the following criteria: 0, no metastasis; 1, bone lesion covering < 1/4 of the bone width; 2, bone lesion involving 1/4∼1/2 of the bone width; 3, bone lesion across 1/2∼3/4 of the bone width; and 4, bone lesion >3/4 of the bone width. The bone metastasis score for each mouse was the sum of the scores of all bone lesions from four limbs. For survival studies, mice were monitored daily for signs of discomfort and were either euthanized all at one time or individually when presenting signs of distress, such as a 10% loss of body weight, paralysis, or head tilting.

Patients and Tumor Tissues

A total of 142 PCa tissues, including 39 PCa tissues with bone metastasis and 103 PCa tissues without bone metastasis, were obtained at The First People’s Hospital of Guangzhou City (Guangzhou, China) between January 2008 and October 2016. Patients were diagnosed based on clinical and pathological evidence, and the specimens were immediately snap-frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen tanks. For the use of these clinical materials for research purposes, prior patient consent and approval from the Institutional Research Ethics Committee were obtained. The clinicopathological features of the patients are summarized in Table 3. The median miR-532-3p expression in PCa tissues was used to stratify high and low expression of miR-532-3p.

Table 3.

Clinicopathological Characteristics in 142 Patients with Prostate Cancer

| Parameters | No. of Cases |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| ≤71 | 72 |

| >71 | 70 |

| Differentiation | |

| Well/moderate | 65 |

| Poor | 77 |

| Serum PSA at diagnosis (μg/mL) | |

| <23.6 | 66 |

| >23.6 | 76 |

| Gleason grade | |

| ≤7 | 81 |

| >7 | 61 |

| miR-532-3p expression | |

| <4.26 | 71 |

| >4.26 | 71 |

| BM status | |

| BM-free | 103 |

| BM | 39 |

PSA, prostate-specific antigen; BM, bone metastasis.

Statistical Analysis

All values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Significant differences were determined using GraphPad 5.0 software (GraphPad, USA). A Student’s t test was used to determine statistical differences between two groups. The chi-square test was used to analyze the relationship between miR-532-3p expression and clinicopathological characteristics. p < 0.05 was considered significant. All experiments were repeated three times.

Author Contributions

P.H. and S.H. developed ideas and drafted the manuscript. Q.W., C.Z., and Z. Lin conducted the experiments and contributed to the analysis of data. S.H., X.P., and D.X. contributed to the analysis of data. Z. Liao and H.H. conducted the experiments. C.Y. and B.W. contributed to the analysis of data and revised the manuscript. D.R. edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to revision of the manuscript and approved the final version for publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81860322, 81872172, 81802555, 81702671, 81660362, and 81902941); the Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (2017A030310149 and 2017ZC0247); the Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (A2018002 and A2018302); the Science and Technology Planning Project of Health and Family Planning Commission of Jiangxi Province (20181026); the Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (2018A030313077 and 2016A030313215); and by the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (201904010440).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omto.2020.03.024.

Contributor Information

Shuai Huang, Email: huang-shuai@hotmail.com.

Peiheng He, Email: hepeiheng1234@sina.com.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Carlin B.I., Andriole G.L. The natural history, skeletal complications, and management of bone metastases in patients with prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;88(12, Suppl):2989–2994. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000615)88:12+<2989::aid-cncr14>3.3.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bubendorf L., Schöpfer A., Wagner U., Sauter G., Moch H., Willi N., Gasser T.C., Mihatsch M.J. Metastatic patterns of prostate cancer: an autopsy study of 1,589 patients. Hum. Pathol. 2000;31:578–583. doi: 10.1053/hp.2000.6698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ren D., Yang Q., Dai Y., Guo W., Du H., Song L., Peng X. Oncogenic miR-210-3p promotes prostate cancer cell EMT and bone metastasis via NF-κB signaling pathway. Mol. Cancer. 2017;16:117. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0688-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park B.K., Zhang H., Zeng Q., Dai J., Keller E.T., Giordano T., Gu K., Shah V., Pei L., Zarbo R.J. NF-κB in breast cancer cells promotes osteolytic bone metastasis by inducing osteoclastogenesis via GM-CSF. Nat. Med. 2007;13:62–69. doi: 10.1038/nm1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sen R., Baltimore D. Multiple nuclear factors interact with the immunoglobulin enhancer sequences. Cell. 1986;46:705–716. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90346-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karin M., Greten F.R. NF-κB: linking inflammation and immunity to cancer development and progression. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:749–759. doi: 10.1038/nri1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayden M.S., Ghosh S. Shared principles in NF-κB signaling. Cell. 2008;132:344–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adhikari A., Xu M., Chen Z.J. Ubiquitin-mediated activation of TAK1 and IKK. Oncogene. 2007;26:3214–3226. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Z.J. Ubiquitin signalling in the NF-kB pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:758–765. doi: 10.1038/ncb0805-758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoesel B., Schmid J.A. The complexity of NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2013;12:86. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang S., Wa Q., Pan J., Peng X., Ren D., Huang Y., Chen X., Tang Y. Downregulation of miR-141-3p promotes bone metastasis via activating NF-κB signaling in prostate cancer. J. Clin. Exp. Cancer Res. 2017;36:173. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0645-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X., Ren D., Wu X., Lin X., Ye L., Lin C., Wu S., Zhu J., Peng X., Song L. miR-1266 contributes to pancreatic cancer progression and chemoresistance by the STAT3 and NF-κB signaling pathways. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2018;11:142–158. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burnett R.M., Craven K.E., Krishnamurthy P., Goswami C.P., Badve S., Crooks P., Mathews W.P., Bhat-Nakshatri P., Nakshatri H. Organ-specific adaptive signaling pathway activation in metastatic breast cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:12682–12696. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen P.C., Cheng H.C., Tang C.H. CCN3 promotes prostate cancer bone metastasis by modulating the tumor-bone microenvironment through RANKL-dependent pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:1669–1679. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Y., Deng J., Rychahou P.G., Qiu S., Evers B.M., Zhou B.P. Stabilization of Snail by NF-κB is required for inflammation-induced cell migration and invasion. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:416–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huber M.A., Azoitei N., Baumann B., Grünert S., Sommer A., Pehamberger H., Kraut N., Beug H., Wirth T. NF-κB is essential for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in a model of breast cancer progression. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:569–581. doi: 10.1172/JCI21358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song R., Song H., Liang Y., Yin D., Zhang H., Zheng T., Wang J., Lu Z., Song X., Pei T. Reciprocal activation between ATPase inhibitory factor 1 and NF-κB drives hepatocellular carcinoma angiogenesis and metastasis. Hepatology. 2014;60:1659–1673. doi: 10.1002/hep.27312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartel D.P. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Velu V.K., Ramesh R., Srinivasan A.R. Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers in health and disease. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2012;6:1791–1795. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2012/4901.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo W., Ren D., Chen X., Tu X., Huang S., Wang M., Song L., Zou X., Peng X. HEF1 promotes epithelial mesenchymal transition and bone invasion in prostate cancer under the regulation of microRNA-145. J. Cell. Biochem. 2013;114:1606–1615. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang C., Yu M., Xie X., Huang G., Peng Y., Ren D., Lin M., Liu B., Liu M., Wang W., Kuang M. miR-217 targeting DKK1 promotes cancer stem cell properties via activation of the Wnt signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2017;38:2351–2359. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X., Liu J., Zang D., Wu S., Liu A., Zhu J., Wu G., Li J., Jiang L. Upregulation of miR-572 transcriptionally suppresses SOCS1 and p21 and contributes to human ovarian cancer progression. Oncotarget. 2015;6:15180–15193. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang S., Zou C., Tang Y., Wa Q., Peng X., Chen X., Yang C., Ren D., Huang Y., Liao Z. miR-582-3p and miR-582-5p suppress prostate cancer metastasis to bone by repressing TGF-β signaling. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2019;16:91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X., Liu F., Lin B., Luo H., Liu M., Wu J., Li C., Li R., Zhang X., Zhou K., Ren D. miR-150 inhibits proliferation and tumorigenicity via retarding G1/S phase transition in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2017;50:1097–1108. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2017.3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ren D., Lin B., Zhang X., Peng Y., Ye Z., Ma Y., Liang Y., Cao L., Li X., Li R. Maintenance of cancer stemness by miR-196b-5p contributes to chemoresistance of colorectal cancer cells via activating STAT3 signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8:49807–49823. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dai Y., Wu Z., Lang C., Zhang X., He S., Yang Q., Guo W., Lai Y., Du H., Peng X., Ren D. Copy number gain of ZEB1 mediates a double-negative feedback loop with miR-33a-5p that regulates EMT and bone metastasis of prostate cancer dependent on TGF-β signaling. Theranostics. 2019;9:6063–6079. doi: 10.7150/thno.36735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren D., Wang M., Guo W., Huang S., Wang Z., Zhao X., Du H., Song L., Peng X. Double-negative feedback loop between ZEB2 and miR-145 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stem cell properties in prostate cancer cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;358:763–778. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-2001-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colden M., Dar A.A., Saini S., Dahiya P.V., Shahryari V., Yamamura S., Tanaka Y., Stein G., Dahiya R., Majid S. MicroRNA-466 inhibits tumor growth and bone metastasis in prostate cancer by direct regulation of osteogenic transcription factor RUNX2. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2572. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Subat S., Inamura K., Ninomiya H., Nagano H., Okumura S., Ishikawa Y. Unique microRNA and mRNA interactions in EGFR-mutated lung adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Med. 2018;7:419. doi: 10.3390/jcm7110419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo W., Chen Z., Chen Z., Yu J., Liu H., Li T., Lin T., Chen H., Zhao M., Li G., Hu Y. Promotion of cell proliferation through inhibition of cell autophagy signalling pathway by Rab3IP is restrained by microRNA-532-3p in gastric cancer. J. Cancer. 2018;9:4363–4373. doi: 10.7150/jca.27533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paydas S., Acikalin A., Ergin M., Celik H., Yavuz B., Tanriverdi K. Micro-RNA (miRNA) profile in Hodgkin lymphoma: association between clinical and pathological variables. Med. Oncol. 2016;33:34. doi: 10.1007/s12032-016-0749-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han J., Wang F., Lan Y., Wang J., Nie C., Liang Y., Song R., Zheng T., Pan S., Pei T. KIFC1 regulated by miR-532-3p promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via gankyrin/AKT signaling. Oncogene. 2019;38:406–420. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0440-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 33.Wang Y., Yang Z., Wang L., Sun L., Liu Z., Li Q., Yao B., Chen T., Wang C., Yang W. miR-532-3p promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by targeting PTPRT. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019;109:991–999. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao B.S., Liu S.G., Wang T.Y., Ji Y.H., Qi B., Tao Y.P., Li H.C., Wu X.N. Screening of microRNA in patients with esophageal cancer at same tumor node metastasis stage with different prognoses. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013;14:139–143. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang L., Lin C., Song L., Wu J., Chen B., Ying Z., Fang L., Yan X., He M., Li J., Li M. MicroRNA-30e∗ promotes human glioma cell invasiveness in an orthotopic xenotransplantation model by disrupting the NF-κB/IκBα negative feedback loop. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:33–47. doi: 10.1172/JCI58849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang L., Wu J., Yang Y., Liu L., Song L., Li J., Li M. Bmi-1 promotes the aggressiveness of glioma via activating the NF-kappaB/MMP-9 signaling pathway. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:406. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Helbig G., Christopherson K.W., 2nd, Bhat-Nakshatri P., Kumar S., Kishimoto H., Miller K.D., Broxmeyer H.E., Nakshatri H. NF-κB promotes breast cancer cell migration and metastasis by inducing the expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:21631–21638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen Z.J. Ubiquitination in signaling to and activation of IKK. Immunol. Rev. 2012;246:95–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01108.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang B., Zhao H., Zhao L., Zhang Y., Wan Q., Shen Y., Bu X., Wan M., Shen C. Up-regulation of OLR1 expression by TBC1D3 through activation of TNFα/NF-κB pathway promotes the migration of human breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2017;408:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen R.R., Zhou A.Y., Kim E., O’Connell J.T., Hagerstrand D., Beroukhim R., Hahn W.C. TRAF2 is an NF-κB-activating oncogene in epithelial cancers. Oncogene. 2015;34:209–216. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang X., Wen Z., Sun L., Wang J., Song M., Wang E., Mi X. TRAF2 regulates the cytoplasmic/nuclear distribution of TRAF4 and its biological function in breast cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013;436:344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.05.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu L., Zhang S., Huan X., Mei Y., Yang H. Down-regulation of TRAF4 targeting RSK4 inhibits proliferation, invasion and metastasis in breast cancer xenografts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018;500:810–816. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.04.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dai Y., Ren D., Yang Q., Cui Y., Guo W., Lai Y., Du H., Lin C., Li J., Song L., Peng X. The TGF-β signalling negative regulator PICK1 represses prostate cancer metastasis to bone. Br. J. Cancer. 2017;117:685–694. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu N., Ren D., Li S., Ma W., Hu S., Jin Y., Xiao S. RCC2 over-expression in tumor cells alters apoptosis and drug sensitivity by regulating Rac1 activation. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:67. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3908-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ren D., Wang M., Guo W., Zhao X., Tu X., Huang S., Zou X., Peng X. Wild-type p53 suppresses the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stemness in PC-3 prostate cancer cells by modulating miR-145. Int. J. Oncol. 2013;42:1473–1481. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ren D., Dai Y., Yang Q., Zhang X., Guo W., Ye L., Huang S., Chen X., Lai Y., Du H. Wnt5a induces and maintains prostate cancer cells dormancy in bone. J. Exp. Med. 2019;216:428–449. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang M., Ren D., Guo W., Huang S., Wang Z., Li Q., Du H., Song L., Peng X. N-cadherin promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell-like traits via ErbB signaling in prostate cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2016;48:595–606. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Y.N., Yin J.J., Abou-Kheir W., Hynes P.G., Casey O.M., Fang L., Yi M., Stephens R.M., Seng V., Sheppard-Tillman H. miR-1 and miR-200 inhibit EMT via Slug-dependent and tumorigenesis via Slug-independent mechanisms. Oncogene. 2013;32:296–306. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.