Abstract

Aortic valve sclerosis is a highly prevalent, poorly characterized asymptomatic manifestation of calcific aortic valve disease and may represent a therapeutic target for disease mitigation. Human aortic valve cusps and blood were obtained from 333 patients undergoing cardiac surgery (n = 236 for severe aortic stenosis, n = 35 for asymptomatic aortic valve sclerosis, n = 62 for no valvular disease), and a multiplex assay was used to evaluate protein expression across the spectrum of calcific aortic valve disease. A subset of six valvular tissue samples (n = 3 for asymptomatic aortic valve sclerosis, n = 3 for severe aortic stenosis) was used to create RNA sequencing profiles, which were subsequently organized into clinically relevant gene modules. RNA sequencing identified 182 protein-encoding, differentially expressed genes in aortic valve sclerosis vs. aortic stenosis; 85% and 89% of expressed genes overlapped in aortic stenosis and aortic valve sclerosis, respectively, which decreased to 55% and 84% when we targeted highly expressed genes. Bioinformatic analyses identified six differentially expressed genes encoding key extracellular matrix regulators: TBHS2, SPARC, COL1A2, COL1A1, SPP1, and CTGF. Differential expression of key circulating biomarkers of extracellular matrix reorganization was observed in control vs. aortic valve sclerosis (osteopontin), control vs. aortic stenosis (osteoprotegerin), and aortic valve sclerosis vs. aortic stenosis groups (MMP-2), which corresponded to valvular mRNA expression. We demonstrate distinct mRNA and protein expression underlying aortic valve sclerosis and aortic stenosis. We anticipate that extracellular matrix regulators can serve as circulating biomarkers of early calcific aortic valve disease and as novel targets for early disease mitigation, pending prospective clinical investigations.

Keywords: aortic stenosis, aortic valve sclerosis, calcific aortic valve disease, genomics, proteomics

INTRODUCTION

Calcific aortic valve disease (CAVD) defines a spectrum of valvulopathy ranging from initial structural valve remodeling to outflow obstruction and constitutes a prevalent source of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality worldwide (26, 39). The condition is degenerative and progressive and is expected to increase in prevalence in parallel with an increasingly elderly population. Few randomized clinical trials have sought to halt or reverse aortic cusp calcification and reduce aortic stenosis (AS), without success (6, 25, 29). Despite a large consensus that the window for therapeutic opportunity for AS is very narrow, little attention has been devoted to the initial phase of CAVD, aortic valve sclerosis (AVSc).

American Heart Association-American College of Cardiology guidelines define AVSc as focal areas of aortic valve (AV) calcification and leaflet thickening with a velocity <2.5 m per second (43). This clinical state is by definition asymptomatic without any hemodynamic derangement related to the valvulopathy, making noninvasive diagnosis exceedingly difficult. Notably, only ~10% of patients with AVSc will develop symptomatic AS. Once AVSc is detected, however, there is an increased risk of cardiovascular events, with reduced survival from the expected event-free survival. At the onset of mild symptoms (early AS), survival deviates even more from expected, with a dramatic decline in cases of severe symptomatic AS (1, 3, 18, 27). Presently, surgical or transcatheter interventions constitute the only effective therapeutic options for AS.

Whereas therapeutic agents such as HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system modulators have mitigated many key elements of CAVD in vitro, no efficacy has been demonstrated during clinical trials (23). This result may be related to the virtually unavoidable focus on patients with symptomatic CAVD who might be beyond the window of opportunity for nonsurgical management, as patients enrolled in prospective studies or clinical trials pertaining to the medical management of CAVD are generally symptomatic at the time of enrollment. In addition, much of the valvular tissue harvested for CAVD studies is obtained from patients with advanced disease. This is particularly problematic, as AS appears to be characterized by irreversible remodeling and decreased valve interstitial cell (VIC) pluripotency, and thus this advanced form of CAVD may not be amenable to nonsurgical intervention (4, 30). AVSc remains a prevalent clinical entity within the spectrum of CAVD and may represent an understudied substrate for novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies (10, 35).

The pathophysiology underlying structural changes during CAVD remains incompletely understood but has been characterized as an interplay between inflammation and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), lipid accumulation, and osteogenic transdifferentiation of VICs, ultimately culminating in hemodynamically significant derangements in valvular microarchitecture and function (5). Prior work from our group has demonstrated differential expression, mRNA variants, protein-protein interactions, and posttranslational modifications of osteopontin, a putative biomarker of CAVD previously implicated in ectopic calcification, at different time-points of CAVD progression, thus purporting the existence of unique biomarker profiles corresponding to different stages of the disease (8, 9, 32, 33, 36, 37, 42). Osteopontin belongs to a heterogeneous family of matricellular proteins previously implicated in CAVD structural valve remodeling (20). We and others have proposed that modulation of matricellular proteins may lead to novel preventative, diagnostic, and therapeutic strategies for CAVD mitigation. For example, we have previously demonstrated that Noggin-mediated antagonism of BMP4 attenuates osteogenic transdifferentiation of VICs (34) and that adenoviral transduction of antioxidant enzymes can reverse VIC transdifferentiation (5). Recently we utilized MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+, a superoxide-dismutase mimic currently being utilized in several ongoing clinical trials, to inhibit VIC activation and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling in a murine model (2). This body of work has emphasized the plasticity of valvular structure and function during the early, asymptomatic stages of CAVD, and has provided further evidence suggesting that AVSc is a promising clinical target for disease management. Herein, we characterize mRNA and both local and circulating protein expression across the spectrum of CAVD and discuss the potential significant clinical implications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

Patients undergoing surgical AV replacement or orthotopic heart transplant (OHT) between 2010 and 2017 were enrolled according to approved Institutional Review Board protocols from University of Pennsylvania (#809349), Columbia University (#AAAR6796), and the Valley Hospital (#NRBUTS1109). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for study enrollment, and clinical information was obtained by patient interview and chart review. Exclusion criteria included presence of bicuspid AV, genetic diseases associated with aortic aneurysm formation such as connective tissue disorders, previous myocardial infarction, severe heart failure (New York Heart Association class IV), endocarditis, and active cancer. Control and AVSc specimens were obtained from patients undergoing OHT. Blood was collected via central venous catheter at the time of surgery or by venipuncture for control and AVSc patients. A total of 333 patients met the inclusion criteria: n = 62 Controls, n = 35 with AVSc, n = 236 with AS. See Table 1 for patient demographics. For RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) analyses, six AV tissue samples were utilized (n = 3 for asymptomatic AVSc, n = 3 for severe AS).

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Control | Sclerotic | Stenotic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 62 | 35 | 236 |

| Age, yr, mean ± SE | 50.61 ± 1.60 | 55.09 ± 1.97 | 74.04 ± 0.57 |

| Sex | 53 men (85.5% | 11 men (31.4%) | 91 men (38.6%) |

| 9 women (14.5%) | 23 women (65.7%) | 145 women (61.4%) | |

| 1 unknown (2.9%) | |||

| Ethnicity | 40 white (64.5%) | 13 white (37.1%) | 216 white (91.5%) |

| 5 black (8.1%) | 9 black (25.7%) | 2 black (0.85%) | |

| 7 Hispanic (11.3%) | 13 unknown (37.1%) | 1 Hispanic (0.42%) | |

| 10 Asian/PI (16.1%) | 2 Asian/PI (0.85%) | ||

| History of smoking | 23 (37.1%) | 4 (11.4%) | 90 (38.1%) |

| Heart failure | 0 | 13 (37.1%) | 33 (14.0%) |

| CAD | 0 | 6 (17.1%) | 122 (51.7%) |

| Diabetes | 4 (6.5%) | 10 (28.6%) | 63 (26.7%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0 | 15 (42.9%) | 129 (54.7%) |

| Hypertension | 3 (4.8%) | 18 (51.4%) | 156 (66.1%) |

CAD, coronary artery disease; PI, Pacific Islander.

RNA-Seq alignments and differentially expressed genes tests.

The RNA-Seq raw paired-end fastq files were aligned in Gencode v19 by STAR with default options. The mapped SAM files were converted to BAM files and sorted by SAMTOOLs. Read depth after sorting ranged from 54 million to 68 million reads with a mean read of 58 million. Transcripts were assembled using Cufflinks version 2.2.1 with template Gencode v19 (40). For each protein-encoding gene we compared the estimated expression level measured as fragments per kilobase of transcript per million (FPKM). This procedure was carried out for all tissues together and then repeated separately for each of the different tissue types: AVSc and AVS. The genes were considered differentially expressed only if their false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted P value (q value) was ≤ 0.05, and the gene enrichment analyses in gene ontology and biological pathways were done utilizing the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) Gene Functional Classification Tool (12). The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in National Center for Biotechnology Information’s (NCBI's) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE138531 (7).

Gene module detection.

The gene modules were generated based on weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA) (19). WGCNA is an R package used to form a correlated gene network based on expression; gene modules are generated if gene expression converges. The program surveyed a list of genes that were differentially expressed between AS and AVSc, generating a “threshold,” which was employed to search for different gene modules based on hierarchical clusters, ultimately yielding the optimal number of gene modules and assigning respective colors. Based on previous simulations, a small cluster number indicates that genes could not be separated based on expression, whereas a very large cluster number indicates insufficient genes in each module.

Measurement of circulating biomarkers in AVS and AVSc.

A Luminex bead-based multiplex assay (Bristol Myers-Squibb, Ewing Township, NJ) of 48 circulating biomarkers previously associated with cardiovascular conditions was performed on 333 patients selected based on their echocardiographic reports. All 48 protein biomarkers were measured from the same aliquot of participant plasma. A complete list of analytes is reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Analytes measured by Luminex

| Analyte | Low Std, pg/ml | Analyte | Low Std, pg/ml |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cystatin-C | 728.4 | TNF RI | 176.5 |

| FABP4 | 938.3 | TSG-14 | 506.2 |

| FAS | 125.5 | VEGF | 23.3 |

| GDF-15 | 40.3 | Adiponectin | 3204.1 |

| ICAM-1 | 6477.4 | ANG-2 | 113.0 |

| IL-1 beta | 41.7 | CHI3-L1 | 275.2 |

| IL-10 | 11.1 | CRP | 116.2 |

| IL-6 | 28.8 | Endoglin | 555.6 |

| IL-8 | 18.6 | Endostatin | 238.7 |

| MMP-12 | 35.4 | Endothelian-1 | 9.5 |

| MMP-2 | 294.1 | FABP3 | 2293.4 |

| MMP-3 | 58.7 | FGF-21 | 497.8 |

| MMP-7 | 572.1 | FGF-23 | 37.0 |

| MMP-8 | 494.1 | Galectin-3 | 21.4 |

| MMP-9 | 304.4 | Lipocalin | 105.3 |

| MPO | 162.6 | NT-Pro-ANP | 193.4 |

| OPN | 3193.4 | OPG | 4.5 |

| pro-BNP | 14.4 | PAI-1 | 25.0 |

| P-Selectin | 236.6 | Syndecan-1 | 181.1 |

| Renin | 313.2 | Syndecan-4 | 78.2 |

| ST2 | 1099.3 | TIMP-4 | 25.5 |

| Tenascin-C | 42.0 | TNF RII | 5.5 |

| TIM-1/KIM-1 | 108.6 | Troponin T | 246.9 |

| TIMP-1 | 32.9 | VEGF R1 | 21.4 |

| TNF alpha | 27.7 |

Statistical analysis.

Continuous and categorical variables were compared between the groups by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and χ2 tests, respectively. mRNA and protein levels were log-transformed to improve the normality of the distribution. Biomarker levels were compared by ANOVA. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed with FDR adjustments when the overall ANOVA test was significant. All probability values are two tailed. Statistical significance was defined alpha < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with CuffDiff (Cufflinks, v 2.2.1) (40).

RESULTS

Identification of functional regulators of the ECM in AVSc.

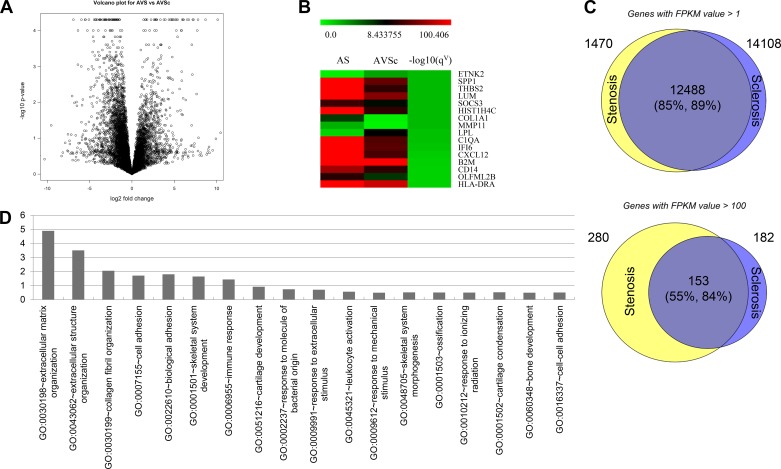

By RNA-Seq we identified 257 differentially expressed genes in AVSc vs. AS (q value ≤ 0.05) including 182 protein-encoding genes (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Table S1; https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10003193.v1). Full data are deposited on the GEO-NCBI database archive with access number GSE138531 (7). Expressed genes in AS and AVSc patients were highly similar: for genes with an FPKM value >1, the overlap rate was 85% and 89% (Supplemental Tables S2, S3, and S4; https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10003259.v1), respectively, for expressed genes in AS and AVSc (Fig. 1C); however, for highly expressed genes (FPKM ≥ 100), the overlap ratio is decreased significantly to 55% and 84%, respectively (Supplemental Tables S5, S6, and S7; https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10003259.v1). The results indicate that although the expressed genes are qualitatively similar, the quantitative expression levels are different for the two phenotypes. A heat map illustrates some of the most differentially expressed genes (Fig. 1B). Notably, this partial list is highly enriched in matricellular proteins previously implicated as ECM regulators such as SPP1 (osteopontin), THBS2, MMPs, LUM, Col11A1, and others. Gene enrichment analysis showed the 182 protein-encoding genes are enriched in disease categories such as IMMUNE (q value = 2.5 × 10−3) and CARDIOVASCULAR (q value = 1.7 × 10−1). Gene Ontology (GO) Consortium-based analyses demonstrated gene enrichment in ECM organization (q value = 5.7 × 10−4) and collagen fibril organization (q value = 5.7 × 10−2) (Fig. 1D). Among those 182 genes, 116 (64%) are expressed to a greater extent in AS, whereas 66 (36%) are expressed to a greater extent in AVSc.

Fig. 1.

Differential gene expression in aortic stenosis (AS) compared with aortic valve sclerosis (AVSc). A: volcano plot demonstrating RNA sequencing results with differential gene expression in AS compared with AVSc. B: heat map of highly expressed genes in AS compared with AVSc, with red and green corresponding to high and low expression, respectively. C: graphical representation of qualitative gene activation in AS and AVSc, stratified by low [fragments per kilobase of transcript per million (FPKM) > 1] and high (FPKM > 100) degrees of gene expression. D: Gene Ontology (GO)-based analysis of gene enrichment among pathways of extracellular matrix and cellular regulation.

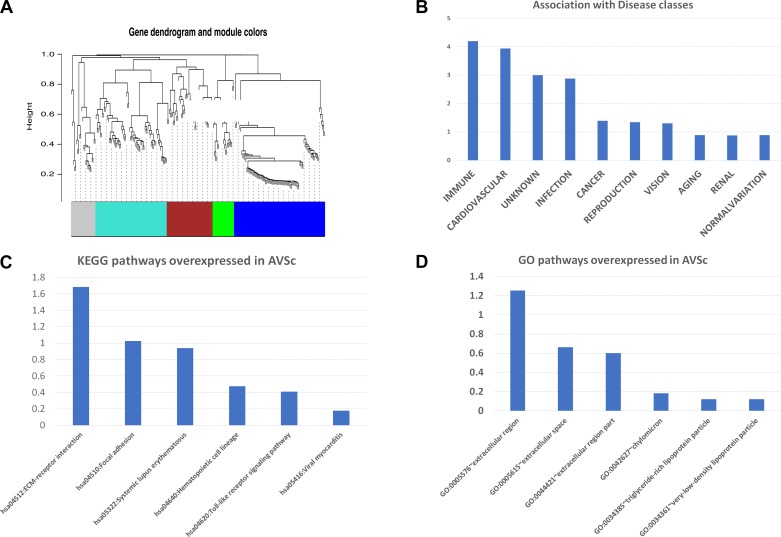

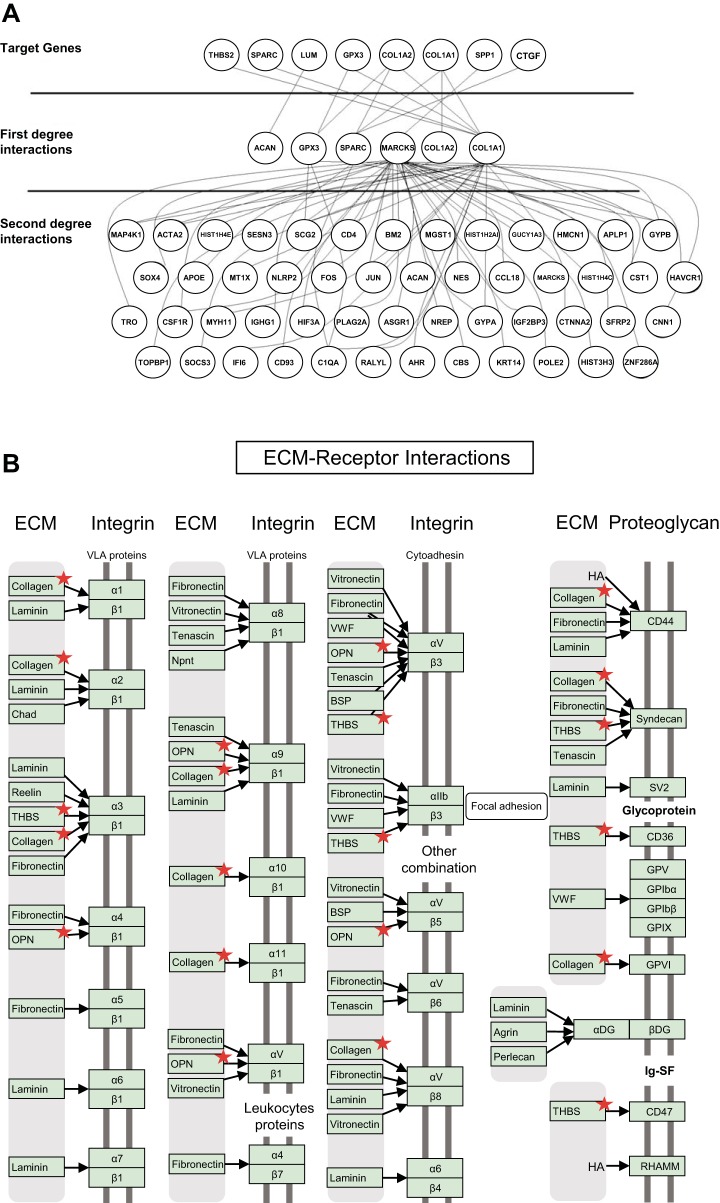

The metabolic processes underlying AVSc are complex, suggesting that the evolution from mild to severe stages of degeneration is likely not determined by a single gene but rather by groups of genes that become integrated into “gene modules.” Gene modules integrate these genes to become functional toward specific metabolic processes. Using the WGCNA algorithm described in materials and methods, we utilized the 182 gene list for gene module analysis. Five gene modules were generated based on WGCNA algorithms for this gene list (clustered by color in Fig. 2A), the largest of which, module light blue, comprises 59 genes. Within this module, only two genes (3%) demonstrate higher expression in the AVSc cohort: ETNK2 and LPL, the latter of which encodes lipoprotein lipase (LpL). Multiple functional enrichments of biological processes previously implicated in the pathogenesis of CAVD resulted for module light blue, including the previously implicated ROS-associated IMMUNE disease category, and important processes in AS such as cell adhesion and ECM receptor regulators identified in Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and GO-based analysis (Fig. 2, B–D). Six genes critical in the remodeling of the ECM were selected based on the RNA-Seq analysis and on their biological relevance to clinical phenotype: THBS2 (encodes thrombospondin-2), SPARC (encodes osteonectin), COL1A2 (encodes alpha-2 type I collagen), COL1A1 (encodes alpha-1 type I collagen), SPP1 (encodes osteopontin), and CTGF (encodes connective tissue growth factor). These genes were cross-referenced with the Biological General Repository for Interaction Datasets (BioGRID), which is a curated biological database of protein-protein interactions, genetic interactions, chemical interactions, and posttranslational modifications. The interacted genes were further filtered only if they were human genes and only if they were included in the 257 differentially expressed gene list mentioned in the previous section. The interacted genes/proteins in first and second degrees are shown in Fig. 3A, illustrating the myriad downstream interactions resultant of first-degree protein interaction. These genes were further analyzed in the context of ECM-receptor interactions, which identified several encoded ECM proteins differentially expressed between AVSc and AS (Fig. 3B), thus linking the aforementioned genes and protein products to their putative roles in ECM regulation and valvular remodeling. Among the relatively small number of genes differentially expressed in AVSc vs. AS, these ECM regulators have profound ramifications within the total number of genes analyzed and may ultimately contribute to valvular remodeling across the spectrum of CAVD.

Fig. 2.

Gene module organization: A: weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA) algorithm-derived gene dendrogram illustrating 5 modules of gene expression. B: gene enrichment profile of the largest gene module (light blue), notable for IMMUNE and CARDIOVASCULAR enrichment. KEGG (C) and GO pathways (D) notable for overexpression of extracellular matrix regulatory genes in aortic valve sclerosis (AVSc).

Fig. 3.

First- and second-degree interactions of differentially expressed aortic valve sclerosis (AVSc) genes with genes and proteins: A: visual representation of the complex and numerous downstream effects of genes highly expressed in AVSc; each node represents a gene, and each line between two nodes indicates an experimentally proven gene interaction; B: differentially expressed genes (indicated by red star) in aortic stenosis (AS) and AVSc demonstrate enrichments in functional pathways, such as in the extracellular matrix (ECM) receptor pathways shown here.

Circulating and tissue biomarkers for the identification of AVSc.

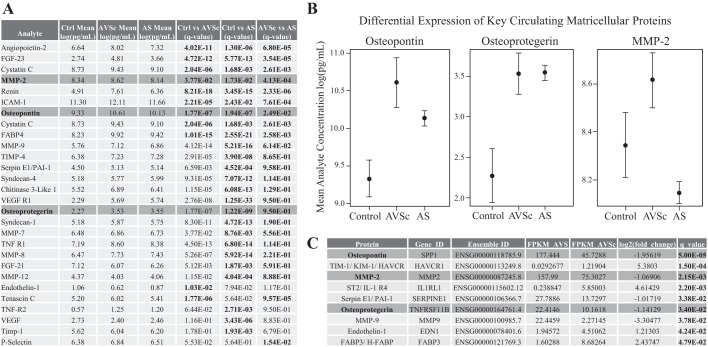

The previous sections highlight the impact of ECM regulators on AV architecture in AVSc. We identified several protein markers that were differentially expressed in each phase of the disease. Figure 4, A and B, demonstrates differential expression for key proteins in Control vs. AVSc, Control vs. AS, and AVSc vs. AS groups, respectively. Among others, we noted: Osteopontin, a matricellular protein key in the early remodeling of the cusps is differentially expressed in Control vs. AS patients (q = 1.94 × 10−7), in agreement with previous reports (9); osteoprotegerin, a marker of osteogenic differentiation, is differentially expressed in controls vs. AS patients (q = 1.22 × 10−9); MMP-2, associated with pathological remodeling and degradation of ECM components, is differentially expressed in AVSc vs. AS patients (q = 4.13 × 10−4). A full list of differentially expressed analytes is reported in Supplemental Table S8 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10003268.v1). Finally, we sought to determine whether the same circulating markers were also differentially expressed in the AV mRNA profiles by RNA-Seq, which yielded results consistent with our protein analyses (see Fig. 4C). A full multivariate analysis of circulating analytes is reported in Supplemental Table S9 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10003268.v1).

Fig. 4.

Multiplex assay for circulating and valvular biomarkers of calcific aortic valve disease. A: differential expression of select matricellular protein expression represented by 95% confidence intervals. B: control and AVSc (Osteopontin, q = 1.94 × 10−7), Control vs. AS (Osteoprotegerin, q = 1.22 × 10−9), and AVSc vs. AS (MMP-2, q = 4.13 × 10−4) cohorts, respectively. C: differential expression of key genes implicated in extracellular remodeling correlates with that of differential protein expression in AVSc vs. AS. Boldface indicates statistical significance. For a full list of differential protein expression, see Supplemental Table S8 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10003268.v1).

DISCUSSION

Despite ongoing sophistication of surgical techniques and technologies associated with definitive CAVD management, there are presently no medical therapies available for the prevention or treatment of the disease (24). Furthermore, the transition from asymptomatic AVSc to symptomatic AS remains poorly characterized. In this study we describe, for the first time, the differential expression of mRNA and protein expression in AVSc compared with AS. Notably, several functional regulators of AV architecture are differentially expressed in both RNA-Seq analyses (AV tissue extracts) and multiplex assays (circulating markers) suggesting their potential diagnostic and therapeutic roles in AVSc.

RNA-Seq demonstrated that, although mRNA expression across the CAVD spectrum is qualitatively similar, there is a significant difference in relative, quantitative mRNA expression in AVSc compared with AS. This novel finding illustrates distinct genomic profiles underlying AVSc and AS, which raises the possibility of preventative or therapeutic strategies tailored to each disease state. This becomes particularly significant for AVSc, as the potential for early recognition and treatment during this asymptomatic clinical state may obviate the need to manage the more advanced, potentially irreversible, and symptomatic stages of AS. Early recognition and management of AVSc as a distinct clinical entity may additionally halt the progression of the known cardiovascular consequences of CAVD including but not limited to myocardial fibrosis, heart failure, aortic insufficiency, and myocardial infarction (17, 28, 41).

Differential mRNA expression was further analyzed within the context of functional gene modules, which identified several putative functional ECM regulators. The largest of these functional modules, module light blue (Fig. 2A), comprises 59 genes. Two of these genes demonstrated elevated expression in the AVSc cohort, notably including the gene encoding LpL. Diffuse LpL expression has previously been demonstrated in stenotic human AVs and has been implicated in fibrocalcific AV remodeling and cardiac myocyte lipid regulation; however, our study is the first to demonstrate a relative increase in expression in AVSc compared with AS (16, 21, 22). Given the putatively atherosclerosis-like mechanism underlying CAVD progression, LpL’s role in the regulation of cardiac and systemic lipid regulation may indicate potential utility as a biomarker or therapeutic target of CAVD progression. Furthermore, previous work by our group and others has identified ECM remodeling as an early pathologic stage of AVSc, characterized by ROS accumulation, inflammation, and VIC activation. VIC activation induces phenotypic changes conducive to osteogenesis, thus constituting one mechanism underlying AV calcification and eventual dysfunction (11, 13). Additional work from our group has demonstrated a functional role for antioxidant therapy in the amelioration of ECM remodeling, sclerosis, and calcification (2).

As demonstrated in Figs. 2 and 3, modulation of the six genes identified through RNA-Seq and subsequent analyses has diverse and profound downstream implications for the functions of ECM constituents and regulators. These selected genes have previously been implicated in CAVD pathogenesis and may constitute novel targets for early disease recognition and therapy. In analyzing the associated gene products, we identified several proteins differentially expressed across the clinical spectrum of CAVD, including but not limited to OPN, a bone matrix protein whose production is augmented by osteogenic VICs and is implicated in both valvular inflammation and mineralization; osteoprotegerin, which has been shown in vivo to attenuate valvular calcification; and MMP-2, which contributes to ECM remodeling through proteolytic digestion of several ECM elements (14, 15, 31, 42). Furthermore, the numerous and complex ECM-receptor interactions implicated in Fig. 3B may explain the calcium-independent processes and remodeling mechanisms underlying the noncalcific aspect of CAVD progression, which may ultimately represent the window of opportunity for disease mitigation. Although the aforementioned proteins have previously been implicated in the pathogenesis of CAVD, their respective expression levels have never been evaluated within a patient population of nonvalvulopathic controls and in the setting of AVSc and AS. This is an important distinction that may explain why clinical trials have failed to yield evidence of beneficial medical CAVD regimens: these prior studies focused on patient cohorts with advanced disease (AS), and, given the difference in mRNA and protein expression between AVSc and AS, results may not be applicable to a patient population characterized by mild, asymptomatic CAVD (9, 38); CAVD therapies that demonstrated promising results in vivo but failed in human studies of AS may be more appropriate for earlier AVSc mitigation and prevention of CAVD progression before the onset of irreversible AS.

There are limitations associated with this study. Whereas the stenotic AVs obtained for our study were excised from patients with isolated severe AS at the time of isolated valve replacement, the explantation of healthy or sclerotic AVs is an exceptionally rare occurrence. Consequently, for the control and sclerotic cohorts, we relied upon AVs explanted from OHT recipients. These valves either lacked radiologic and gross evidence of aortic valvulopathy (control) or met the radiologic criteria for AVSc without any gross or radiologic evidence of AS. Although the etiologies of these patients’ heart failure were nonvalvular in nature, the possibility of valvular remodeling secondary to the primary pathology must be considered. Furthermore, although the samples were ultimately obtained from patients with similar cardiovascular pathologies and comorbidities within and between each study cohort, nonidentical patient demographics and comorbidities, particularly between the OHT samples and AV replacement samples, remain a potential source of confounding.

In the absence of reliable strategies for the mitigation of symptomatic CAVD, prevention and early recognition are essential in reducing the quantity of patients requiring AV repair or replacement. Radiologic limitations in the diagnosis of AVSc make early recognition of this asymptomatic condition exceptionally difficult. Consequently, the identification of protein biomarkers associated with early CAVD may constitute a significant component of screening and surveillance strategies for patients at risk for the disease. We have demonstrated distinct and congruent mRNA and protein expression underlying two ends of the CAVD spectrum: AVSc and AS. We anticipate that functional ECM regulators can serve as both circulating biomarkers of early CAVD as well as novel targets for early CAVD mitigation, pending future prospective clinical investigations.

GRANTS

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01-HL-122805 (to G. Ferrari), R01-HL-131872 (to G. Ferrari and R. J. Levy), and T32-HL-007854 (to A. P. Kossar); The Kibel Fund for Aortic Valve Research (to G. Ferrari and R. J. Levy); The Valley Hospital Foundation “Marjorie C. Bunnel” charitable fund (to G. Ferrari); and both Erin’s Fund and the William J. Rashkind Endowment of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (to R. J. Levy).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

W.A., J.B.G., Y.L., A.S., D.J.R., R.J.L., and G.F. conceived and designed research; W.A., Y.L., A.S., L.S., L.Z., M.E.C., Z.L., M.Y., and N.R. performed experiments; A.P.K., W.A., Y.L., A.S., S.L.C., L.S., L.Z., M.E.C., Z.L., M.Y., N.R., and G.F. analyzed data; A.P.K., W.A., J.B.G., Y.L., A.S., S.L.C., N.R., D.J.R., R.J.L., and G.F. interpreted results of experiments; A.P.K., W.A., Y.L., A.S., S.L.C., and G.F. prepared figures; A.P.K. drafted manuscript; A.P.K., S.L.C., R.J.L., and G.F. edited and revised manuscript; A.P.K., W.A., J.B.G., Y.L., A.S., S.L.C., L.S., L.Z., M.E.C., Z.L., M.Y., N.R., D.J.R., R.J.L., and G.F. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aikawa E, Otto CM. Look more closely at the valve: imaging calcific aortic valve disease. Circulation 125: 9–11, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.073452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anselmo W, Branchetti E, Grau JB, Li G, Ayoub S, Lai EK, Rioux N, Tovmasyan A, Fortier JH, Sacks MS, Batinic-Haberle I, Hazen SL, Levy RJ, Ferrari G. Porphyrin-Based SOD Mimic MnTnBu OE -2-PyP5+ Inhibits Mechanisms of Aortic Valve Remodeling in Human and Murine Models of Aortic Valve Sclerosis. J Am Heart Assoc 7: e007861, 2018. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumgartner H, Otto CM. Aortic stenosis severity: do we need a new concept? J Am Coll Cardiol 54: 1012–1013, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogdanova M, Zabirnyk A, Malashicheva A, Enayati KZ, Karlsen TA, Kaljusto M-L, Kvitting J-PE, Dissen E, Sullivan GJ, Kostareva A, Stensløkken K-O, Rutkovskiy A, Vaage J. Interstitial cells in calcified aortic valves have reduced differentiation potential and stem cell-like properties. Sci Rep 9: 12934, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49016-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Branchetti E, Sainger R, Poggio P, Grau JB, Patterson-Fortin J, Bavaria JE, Chorny M, Lai E, Gorman RC, Levy RJ, Ferrari G. Antioxidant enzymes reduce DNA damage and early activation of valvular interstitial cells in aortic valve sclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33: e66–e74, 2013. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowell SJ, Newby DE, Prescott RJ, Bloomfield P, Reid J, Northridge DB, Boon NA; Scottish Aortic Stenosis and Lipid Lowering Trial, Impact on Regression (SALTIRE) Investigators . A randomized trial of intensive lipid-lowering therapy in calcific aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 352: 2389–2397, 2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 207–210, 2002. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrari G, Sainger R, Beckmann E, Keller G, Yu P-J, Monti MC, Galloway AC, Weiss RL, Vernick W, Grau JB. Validation of plasma biomarkers in degenerative calcific aortic stenosis. J Surg Res 163: 12–17, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grau JB, Poggio P, Sainger R, Vernick WJ, Seefried WF, Branchetti E, Field BC, Bavaria JE, Acker MA, Ferrari G. Analysis of osteopontin levels for the identification of asymptomatic patients with calcific aortic valve disease. Ann Thorac Surg 93: 79–86, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hermans H, Herijgers P, Holvoet P, Verbeken E, Meuris B, Flameng W, Herregods M-C. Statins for calcific aortic valve stenosis: into oblivion after SALTIRE and SEAS? An extensive review from bench to bedside. Curr Probl Cardiol 35: 284–306, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins CL, Isbilir S, Basto P, Chen IY, Vaduganathan M, Vaduganathan P, Reardon MJ, Lawrie G, Peterson L, Morrisett JD. Distribution of alkaline phosphatase, osteopontin, RANK ligand and osteoprotegerin in calcified human carotid atheroma. Protein J 34: 315–328, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s10930-015-9620-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Tan Q, Collins JR, Alvord WG, Roayaei J, Stephens R, Baseler MW, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. The DAVID Gene Functional Classification Tool: a novel biological module-centric algorithm to functionally analyze large gene lists. Genome Biol 8: R183, 2007. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hulin A, Hego A, Lancellotti P, Oury C. Advances in Pathophysiology of Calcific Aortic Valve Disease Propose Novel Molecular Therapeutic Targets. Front Cardiovasc Med 5: 21, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2018.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jian B, Jones PL, Li Q, Mohler ER III, Schoen FJ, Levy RJ. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 is associated with tenascin-C in calcific aortic stenosis. Am J Pathol 159: 321–327, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61698-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaden JJ, Vocke DC, Fischer CS, Grobholz R, Brueckmann M, Vahl CF, Hagl S, Haase KK, Dempfle CE, Borggrefe M. Expression and activity of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in calcific aortic stenosis. Z Kardiol 93: 124–130, 2004. doi: 10.1007/s00392-004-1021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan RS, Lin Y, Hu Y, Son N-H, Bharadwaj KG, Palacios C, Chokshi A, Ji R, Yu S, Homma S, Schulze PC, Tian R, Goldberg IJ. Rescue of heart lipoprotein lipase-knockout mice confirms a role for triglyceride in optimal heart metabolism and function. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 305: E1339–E1347, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00349.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kupari M, Laine M, Turto H, Lommi J, Werkkala K. Circulating collagen metabolites, myocardial fibrosis and heart failure in aortic valve stenosis. J Heart Valve Dis 22: 166–176, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurtz CE, Otto CM. Aortic stenosis: clinical aspects of diagnosis and management, with 10 illustrative case reports from a 25-year experience. Medicine (Baltimore) 89: 349–379, 2010. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181fe5648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 9: 559, 2008. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lok ZSY, Lyle AN. Osteopontin in Vascular Disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 39: 613–622, 2019. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahmut A, Boulanger M-C, Fournier D, Couture C, Trahan S, Pagé S, Arsenault B, Després J-P, Pibarot P, Mathieu P. Lipoprotein lipase in aortic valve stenosis is associated with lipid retention and remodelling. Eur J Clin Invest 43: 570–578, 2013. doi: 10.1111/eci.12081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mead JR, Ramji DP. The pivotal role of lipoprotein lipase in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res 55: 261–269, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00405-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moura LM, Ramos SF, Zamorano JL, Barros IM, Azevedo LF, Rocha-Gonçalves F, Rajamannan NM. Rosuvastatin affecting aortic valve endothelium to slow the progression of aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 49: 554–561, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myasoedova VA, Ravani AL, Frigerio B, Valerio V, Moschetta D, Songia P, Poggio P. Novel pharmacological targets for calcific aortic valve disease: Prevention and treatments. Pharmacol Res 136: 74–82, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP III, Guyton RA, O’Gara PT, Ruiz CE, Skubas NJ, Sorajja P, Sundt TM III, Thomas JD; ACC/AHA Task Force Members . 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 129: 2440–2492, 2014. [Erratum in Circulation 129: e650, 2014] doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otto CM. Calcific aortic valve disease: new concepts. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 22: 276–284, 2010. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owens DS, Otto CM. Is it time for a new paradigm in calcific aortic valve disease? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2: 928–930, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park JY, Ryu SK, Choi JW, Ho KM, Jun JH, Rha S-W, Park S-M, Kim HJ, Choi BG, Noh Y-K, Kim S. Association of inflammation, myocardial fibrosis and cardiac remodelling in patients with mild aortic stenosis as assessed by biomarkers and echocardiography. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 41: 185–191, 2014. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parolari A, Tremoli E, Songia P, Pilozzi A, Di Bartolomeo R, Alamanni F, Mestres CA, Pacini D. Biological features of thoracic aortic diseases. Where are we now, where are we heading to: established and emerging biomarkers and molecular pathways. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 44: 9–23, 2013. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pawade TA, Newby DE. Treating aortic stenosis: arresting the snowball effect. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 13: 461–463, 2015. doi: 10.1586/14779072.2015.1037284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perrotta I, Sciangula A, Aquila S, Mazzulla S. Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Expression in Calcified Human Aortic Valves: A Histopathologic, Immunohistochemical, and Ultrastructural Study. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 24: 128–137, 2016. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poggio P, Branchetti E, Grau JB, Lai EK, Gorman RC, Gorman JH III, Sacks MS, Bavaria JE, Ferrari G. Osteopontin-CD44v6 interaction mediates calcium deposition via phospho-Akt in valve interstitial cells from patients with noncalcified aortic valve sclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34: 2086–2094, 2014. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.303017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poggio P, Grau JB, Field BC, Sainger R, Seefried WF, Rizzolio F, Ferrari G. Osteopontin controls endothelial cell migration in vitro and in excised human valvular tissue from patients with calcific aortic stenosis and controls. J Cell Physiol 226: 2139–2149, 2011. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poggio P, Sainger R, Branchetti E, Grau JB, Lai EK, Gorman RC, Sacks MS, Parolari A, Bavaria JE, Ferrari G. Noggin attenuates the osteogenic activation of human valve interstitial cells in aortic valve sclerosis. Cardiovasc Res 98: 402–410, 2013. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajamannan NM, Greve AM, Moura LM, Best P, Wachtell K. SALTIRE-RAAVE: targeting calcific aortic valve disease LDL-density-radius theory. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 13: 355–367, 2015. doi: 10.1586/14779072.2015.1025058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sainger R, Grau JB, Branchetti E, Poggio P, Lai E, Koka E, Vernick WJ, Gorman RC, Bavaria JE, Ferrari G. Comparison of transesophageal echocardiographic analysis and circulating biomarker expression profile in calcific aortic valve disease. J Heart Valve Dis 22: 156–165, 2013. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sainger R, Grau JB, Poggio P, Branchetti E, Bavaria JE, Gorman JH III, Gorman RC, Ferrari G. Dephosphorylation of circulating human osteopontin correlates with severe valvular calcification in patients with calcific aortic valve disease. Biomarkers 17: 111–118, 2012. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2011.642407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teo KK, Corsi DJ, Tam JW, Dumesnil JG, Chan KL. Lipid lowering on progression of mild to moderate aortic stenosis: meta-analysis of the randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials on 2344 patients. Can J Cardiol 27: 800–808, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Towler DA. Molecular and cellular aspects of calcific aortic valve disease. Circ Res 113: 198–208, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol 28: 511–515, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yarbrough WM, Mukherjee R, Ikonomidis JS, Zile MR, Spinale FG. Myocardial remodeling with aortic stenosis and after aortic valve replacement: mechanisms and future prognostic implications. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 143: 656–664, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu P-J, Skolnick A, Ferrari G, Heretis K, Mignatti P, Pintucci G, Rosenzweig B, Diaz-Cartelle J, Kronzon I, Perk G, Pass HI, Galloway AC, Grossi EA, Grau JB. Correlation between plasma osteopontin levels and aortic valve calcification: potential insights into the pathogenesis of aortic valve calcification and stenosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 138: 196–199, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yutzey KE, Demer LL, Body SC, Huggins GS, Towler DA, Giachelli CM, Hofmann-Bowman MA, Mortlock DP, Rogers MB, Sadeghi MM, Aikawa E. Calcific aortic valve disease: a consensus summary from the Alliance of Investigators on Calcific Aortic Valve Disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34: 2387–2393, 2014. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.302523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]