Abstract

Sugar 1,2-orthoesters are by-products of chemical glycosylation reactions that can be subsequently rearranged in situ to give trans glycosides. They have been used as donors in the synthesis of the latter glycosides with good regio- and stereo-selectivity. Alkyl α-(1 → 2) linked mannopyranosyl disaccharides have been reported as the major products from the rearrangement of mannopyranosyl orthoesters. Recent studies in this laboratory have shown that α-(1 → 2) linked mannopyranosyl di-, tri- and tetrasaccharides can be obtained in one step from mannopyranosyl allyl orthoester under optimized reaction conditions. In addition to the expected mono- and disaccharides (56%), allyl 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranoside and allyl 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-Oacetyl-α-D-mannopyranoside were obtained in 23% and 6% isolated yields, respectively, from the oligomerization of a β-D-mannopyranosyl allyl 1,2-orthoester, along with small amounts of higher DP oligomers. Possible mechanisms for the oligomerization and side reactions are proposed based on NMR and mass spectrometric data.

Keywords: Oligosaccharide, Orthoester, Self-condensation, Oligomerization

1. Introduction

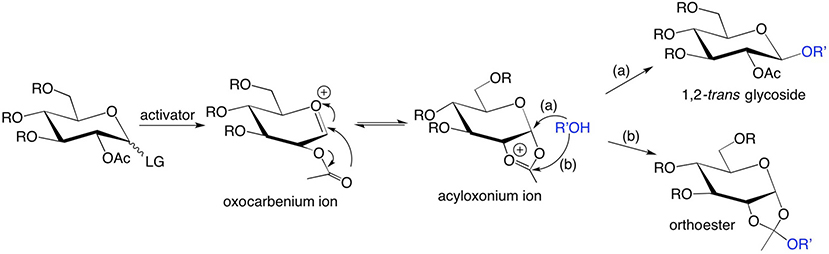

The structure of the protecting group on O2 of aldopyranosyl ring donors can greatly affect the stereochemical outcome of chemical glycosylation. For example, O-acetyl groups stabilize oxocarbenium ion intermediates by forming stable cyclic acyloxonium ion intermediates [1,2]. The acyloxonium ion intermediate provides two sites for nucleophilic attack by an acceptor, resulting in two different products (Scheme 1), one being the desired 1,2-trans glycoside (route a in Scheme 1). The second product is a sugar 1,2-orthoester, which is an undesired by-product of the reaction (route b in Scheme 1) [3–5].

Scheme 1.

Formation of (a) a 1,2-trans-glycoside via intramolecular rearrangement of an oxocarbenium ion intermediate involving the acyl oxygens at C2, followed by SN2 ring-opening of an acyloxonium ion intermediate involving R’OH, and (b) an orthoester via nucleophilic attack of the acyloxonium ion intermediate by R’OH.

Although 1,2-orthoesters are undesired side products of chemical glycosylation, recent studies have revealed their value as protecting groups and as glycosyl donors [6]. Orthoesters are stable under neutral and basic conditions and can serve as effective transient protecting groups. Glycosyl 1,2-orthoesters hydrolyze to the corresponding 2-O-acyl reducing sugars, which serve as precursors in the construction of glycosylation donors. They can also be transformed into 1-O-acetates with trifluoroacetic acid. One such application involves the use of 1,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranoside to prepare 2-deoxy-2-[19F] fluoro-D-glucose [7]. Orthoesters also react with alcohols under mildly acidic conditions [8], an example of which is the well-known Johnson-Claisen rearrangement. Sugar 1,2-orthoesters show similar reactivities [9,10] and utilities in the formation of oligosaccharides. Kong utilized them to regioselectively synthesize oligosaccharides with minimally-protected acceptors, and Fraser-Reid utilized them in the synthesis of numerous targets [2,11]. Lindhorst reported more than 20 years ago that an allyl disaccharide formed in an unusual side-reaction during orthoester rearrangement [12]. Kong later found that a methyl α-mannopyranosyl disaccharide formed from the rearrangement of the corresponding methyl orthoester, and successfully used the latter as the building block in the synthesis of large oligosaccharides [1,6]. A mechanism was proposed [6a,10], and mono- and disaccharides were reported as the only products other than those generated by hydrolysis. Recent studies in this laboratory have shown that additional short-chain trans-(1 → 2) linked oligosaccharides can be synthesized in one step during the self-condensation of sugar allyl orthoesters, and can serve as building blocks in the synthesis of high-mannose N-glycans or used directly to prepare mannose oligosaccharides. Self-condensation gave a mixture of short-chain oligosaccharides ranging from mono- to octa-saccharides, with di- and trisaccharides obtained as the major products (~56% and ~23% isolated yields, respectively).

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Characterization of reaction products

Trans (1 → 2) O-glycosidic linkages involving α-D-mannopyranosyl residues are abundant in high-mannose N-glycans such as 1 and other biologically important glycoconjugates. These sub-fragments have been synthesized from D-mannose via transglycosylation using α-mannosidases [13]. For example, Matsuo and coworkers obtained ~14 mg of αMan-(1 → 2)-αMan-(1 → 2)-αManOH from 10 g of D-mannose using this approach. Subsequent chemical syntheses of trans (1 → 2) linked α-mannopyranosyl di- and trisaccharides have been reported as precursors to the αMan-(1 → 2)-αMan-(1 → 2)-αMan arm attached to βMan (residue 3) in high-mannose N-glycan 1 in improved yield over enzymatic synthesis [14]. The latter chemical methods involved stepwise construction using a mannose monosaccharide as the starting material. For example, Matsuo and coworkers prepared a mono-glucosylated high-mannose dodecasaccharide using a mannose trisaccharide precursor [14c]. This route involved more than ten steps to give an orthogonally protected mannosyl trisaccharide precursor in an overall yield of <10%.

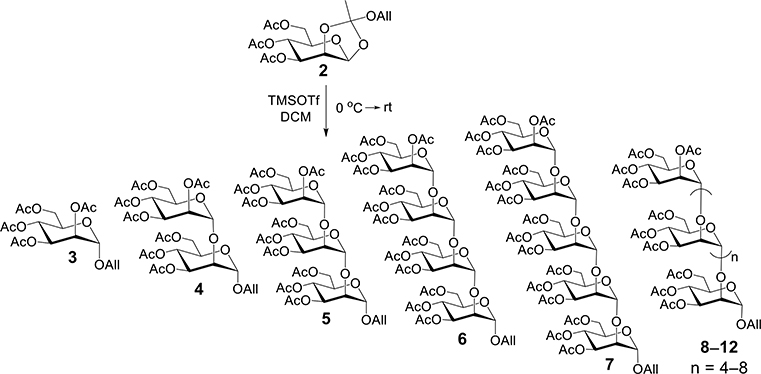

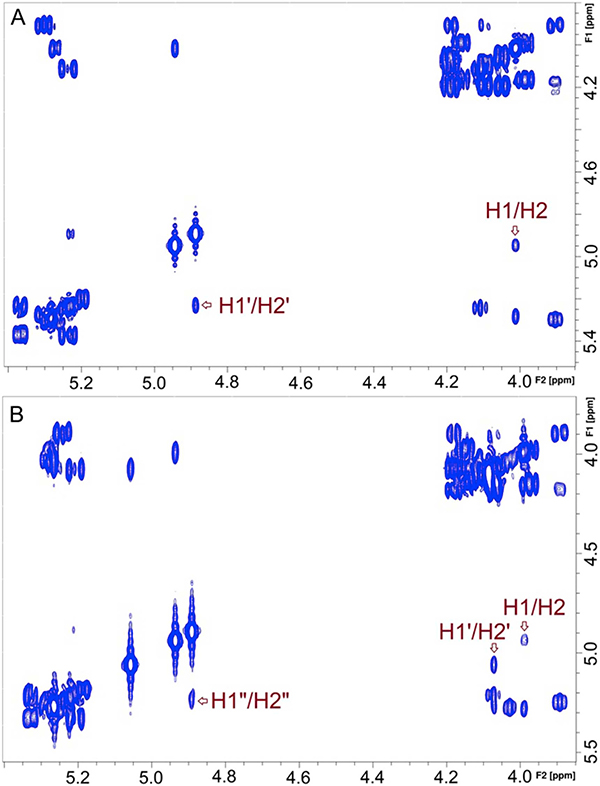

During recent chemical syntheses [15] of nested fragments of 1, the αMan-(1 → 2)-αMan-(1 → 2)-αMan arm appended to βMan (residue 3) was to be constructed from a mannose monosaccharide acceptor and a αMan-(1 → 2)-αMan disaccharide donor. The latter was to be derived from an αMan-(1 → 2)-αMan product obtained from the self-condensation of an acylated mannosyl orthoester [10,12]. It was found that the self-condensation of 3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-1,2-O-(allyloxyethylidene)-β-D-mannopyranose (2) produced polar products in addition to the expected monosaccharide 3 and disaccharide 4, all having lower Rf values on TLC than 2 (Scheme 2). After column chromatography, the two major reaction products were isolated in high purity and were identified as [αMan-(1 → 2)-αMan]x congeners. The least polar and most abundant congener was found to be α-D-Man-(1 → 2)-α-D-Man-OAll (4) as determined by NMR and MS analyses, which is consistent with previous reports [12]. 1D 1H (Fig. 1A) and 13C{1H} NMR spectra of 4 (see Supplementary Information) gave chemical shifts identical to those reported previously [6,12]. Two H1–H2 cross peaks (Fig. 2A) observed at 4.89 ppm/5.22 ppm and 4.93 ppm/4.02 ppm in the 2D 1H–1H gCOSY spectrum confirmed the O-glycosidic linkage to be α-(1 → 2) based on the H2’ signal for the O2-acetylated αMan residue being significantly downfield (5.22 ppm) of the signal arising from H2 of the O2-glycosylated αMan residue (4.02 ppm).

Scheme 2.

Monosaccharide 3 and allyl α-(1 → 2)-mannopyranosyl oligosaccharides 4–12 produced from the self-condensation of 3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-1,2-O-(allyloxyethylidene)-β-D-mannopyranose (2).

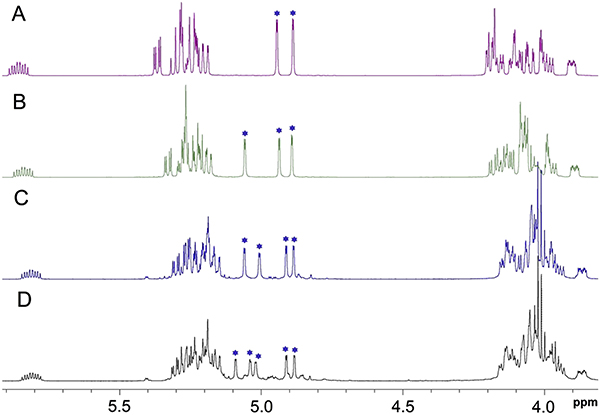

Fig. 1.

Partial 1D 1H NMR spectra of isolated αMan-(1 → 2)-αMan linked oligosaccharides 4 (A), 5 (B), 6 (C) and 7 (D) obtained from the self-polymerization of orthoester 2, showing the anomeric H1 signals labeled with blue stars. (For interpretation of the colored regions in this figure, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 2.

Partial 1H–1H gCOSY spectra of two αMan-containing homo-oligo-saccharides containing α-(1 → 2) O-glycosidic linkages obtained from the self-condensation of 2. (A) Disaccharide 4. (B) Trisaccharide 5.

The 1D 1H NMR spectrum of the more polar compound contained three signals at 4.9–5.1 ppm (anomeric hydrogen region) (Fig. 1B), suggesting trisaccharide (5) as the likely product. Mass spectrometric analysis gave a molecular ion at m/z 987.2938, which matches the calculated mass of 5 (see Supplementary Information). The 2D 1H–1H gCOSY spectrum (Fig. 2B) confirmed the linkage to be α-(1 → 2) in that the three H1–H2 cross peaks at 4.88 ppm/5.22 ppm, 4.92 ppm/3.98 ppm and 5.06 ppm/4.06 ppm indicated that only one H2 resided on a O2-acetylated αMan residue. The isolated yield of 5 was 23% or less depending on the reaction conditions.

Other products isolated from the reaction mixture included the expected monosaccharide, allyl tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranoside (3), which migrated most rapidly on TLC and gave analytical data matching that reported previously. More polar products, which migrated similarly on TLC, were isolated in reduced purity. 1D 1H NMR analysis of the latter (Fig. 1C and D) indicated that two of these products were αMan-(1 → 2)-[αMan-(1 → 2)]2-αMan (6) and αMan-(1 → 2)-[αMan-(1 → 2)]3-αMan (7) based on the number of anomeric hydrogen signals observed in their 1H NMR spectra (anomeric region 4.8–5.1 ppm), and their molecular masses determined from MS analysis (see Supplementary Information). The 2D 1H–1H gCOSY spectrum of 6 (see Supplementary Information) is similar to those of 4 and 5 and confirmed its constituent O-glycosidic linkages to be α-(1 → 2).

Additional five products 8–12 migrated on TLC very closely to 6 and 7, but they could not be fully characterized due to their small quantities and similar polarities. ESI-MS analyses indicated that they are higher molecular weight [αMan-(1 → 2)-αMan]x congeners (see Supplementary Information). An attempt was made to use ESI-MS to determine the relative abundances of these products, but the data were complicated by multiple signals caused by molecular fragmentation. LC-MS suggested the presence of minor products having structures different from the expected allyl acylated α-(1 → 2)-mannopyranosyl oligosaccharides (see Supplementary Information). Some gave mass fragments consistent with a loss of 40 or 42 amu, indicating the loss of allyl or acetyl groups, respectively. Based on the available analytical data, the α-(1 → 2)-mannopyranosyl oligosaccharides shown in Scheme 2 are believed to be the major products generated from the self- condensation of 3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-1,2-O-(allyloxyethylidene)-β-D-mannopyranose (2).

2.2. Mechanistic considerations

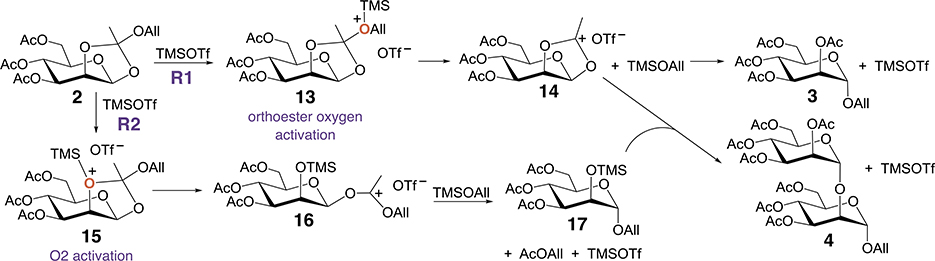

Chemical mechanisms proposed by Kong [6] and Linhorst [12] that were invoked to explain the formation of disaccharide 4 do not explain the formation of oligomers 5–12 and the formation of reaction by-products observed during the self-polymerization of 2. Four oxygen atoms of orthoester 2 [16] can potentially be activated by TMS during rearrangement, leading to different intermediates and products. Based on our results and those in prior reports (Table 1), the activation of the orthoester oxygen and O2 in 2 leads to reaction products 3 and 4, respectively (Scheme 3). Intermediate 14, produced via route R1, serves as an electrophile in reaction with TMSOAll to give 3, and in reaction with intermediate 17, produced from O2-activated 15 via route R2, to give disaccharide 4. Routes R1 and R2 are catalytic in that the net consumption of TMSOTf is zero, and if both processes are concurrent, only AcOAll accumulates as a non-carbohydrate end-product.

Table 1.

Product distributions observed from the self-condensation of 2 under different reaction conditions.

| aglycone group | protecting group | conc. (mM) | reaction T (°C) | catalyst (eq.) | product distributions (%) |

source | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | other products | ||||||

| allyl | Ac | 350 | 0 | TMSOTf (0.03) | 12 | 51 | 20 | 5 | npa | minor | b |

| allyl | Ac | 160 | 0 | TMSOTf (0.1) | 25 | 47 | 13 | 2 | 1 | minor | b |

| allyl | Ac | 322 | −30 | TMSOTf (0.01) | 6 | 56 | 23 | 6 | np | minor | b |

| allyl | Ac | 210 | −30 | TMSOTf (0.03) | 6 | 53 | 22 | 6 | 2 | minor | b |

| allyl | Ac | 35 | 0 | TMSOTf (0.03) | 12 | ~38 | np | np | np | obsc | b |

| allyl | Ac | 130 | 0 | TMSOTf (0.2) | 15 | 29 | nrd | nr | nr | nr | ref. 12 |

| allyl | Bz | 300 | −40 | TMSOTf (0.03) | 20 | 66 | nr | nr | nr | nr | ref. 6(g) |

| Me | Ac | NA | −30 | BF3·Et2O (0.3) | <5 | nr | nr | nr | nr | 86% (25) | ref. 11(e) |

np = product detected but not isolated in pure form, so its percentage could not be determined.

This study.

obs = a significant amount of these products co-eluted with 4–7 but their percentages could not be determined.

nr = none reported.

Scheme 3.

The partitioning of orthoester 2 between two routes, R1 and R2, to give monosaccharide 3 and disaccharide 4, respectively.

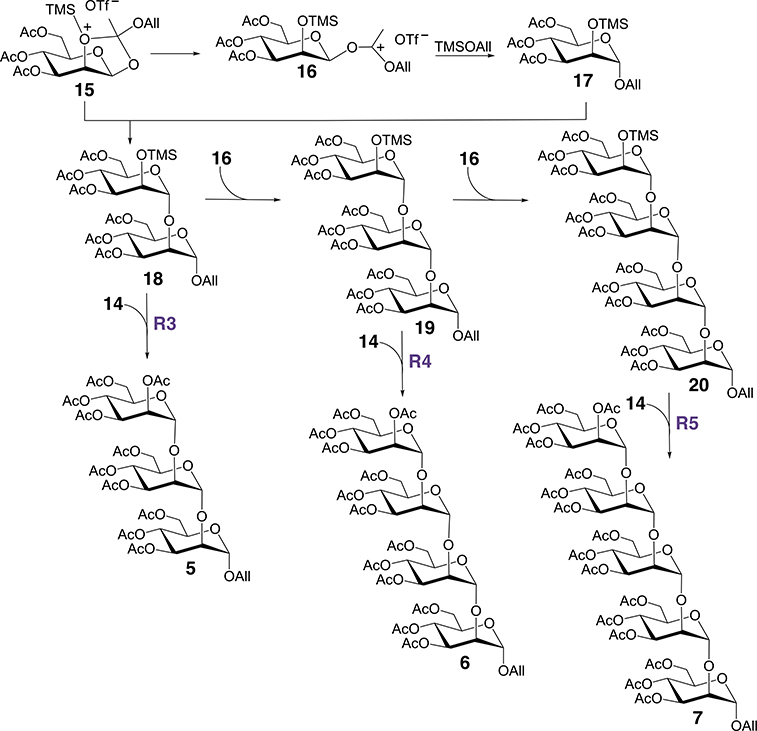

Route 2 in Scheme 3 is believed to play a key role in the production of oligosaccharides 5–7 as shown in Scheme 4. The condensation of 15 and 17 gives disaccharide 18, which is then subject to glycosylation by donor 16 to give trisaccharide 19. A similar glycosylation of 19 by 16 gives tetrasaccharide 20. Compounds 18–20 share a common TMS-activated O2 in their non-reducing terminal αMan residues, rendering them potent nucleophiles in glycosylation reactions with donor 14 (see routes R3–R5 in Scheme 4) generated from route 1 (Scheme 3). In principle, the iterative process described in Scheme 4 can continue beyond 20 to give higher-order oligomers 8–12 (Scheme 2).

Scheme 4.

Proposed mechanism for the formation of oligosaccharides 5–7 during the self-condensation of orthoester 2. Intermediates 15–17 arise from route R2 shown in Scheme 3. Both 14 and 16 serve as glycosyl donors in SN2-like processes that result in inversion of configuration at C1 of the donor.

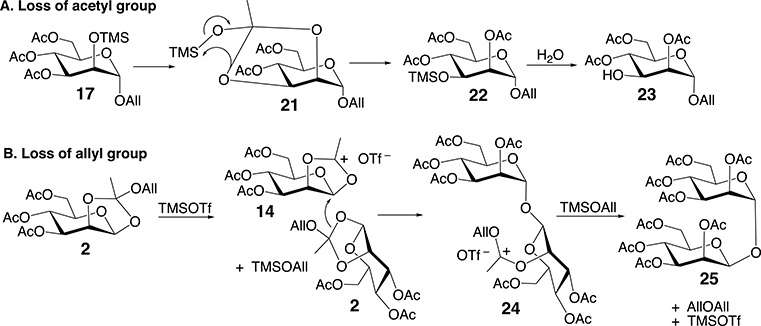

Based on Scheme 4, larger oligomers 7–12 should be favored at high reactant concentrations, whereas oligomers 4–6 and monosaccharide 3 should be the major products at low reactant concentrations. However, NMR and MS analyses of partially purified products generated at dilute reactant concentration (35 mM 2) showed the presence of by-products that co-eluted with α-(1 → 2) oligomers. NMR and mass spectrometric (see Supplementary Information) data indicated the existence of two reaction pathways shown in Scheme 5. One of these pathways (A; Scheme 5) produces monosaccharide 23, the 3-O-deacetylated derivative of 3. Experimental evidence of the formation of 23 derives from MS data showing a molecular ion having a m/z value that is 42 amu smaller than that observed for 3 (loss of –COCH3), while the 1D 1H NMR spectrum of 23 contains an H3 signal shifted upfield, relative to that in 3, due to O3 deacetylation.

Scheme 5.

Two reaction pathways detected during the self-condensation of 2, giving by-products 23 and 25.

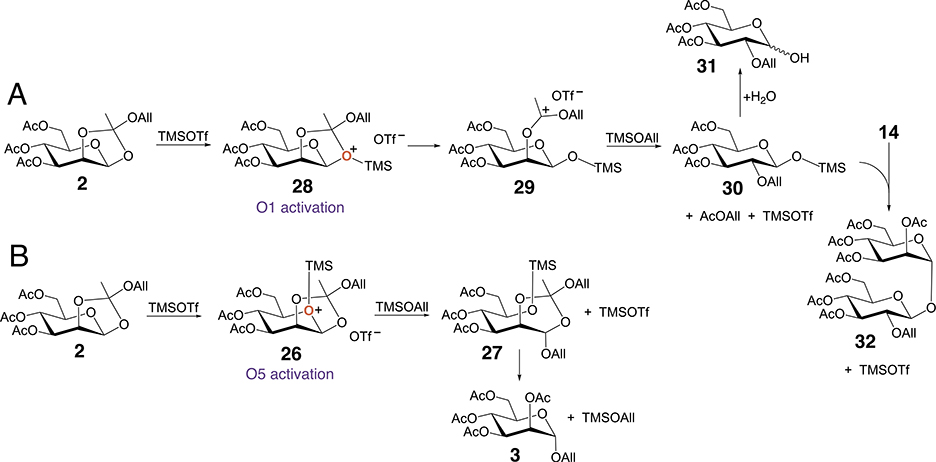

MS analysis of 25 gave a molecular ion having an m/z of 659.1816, and NMR showed no evidence of an allyl group in the structure. 1D 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 25 gave signals that matched those reported for an α,β-(1 → 1) linked disaccharide (see Supplementary Information) [11e]. These results indicate that the type(s) of oxygen activation of orthoester 2 by TMS may depend on reactant concentrations and on the Lewis acid used in the activation (TMSOTf vs BF3.Et2O) (Table 1) (Scheme 6). For example, O5 activation provides another route to 3, whereas O1 activation may lead to monosaccharide 31 and α,β-(1 → 1) disaccharide 32. The activity of the latter pathway remains uncertain because it is difficult to detect 32 in the presence of 25. Related sidereactions appear to occur during the rearrangement of galactose orthoester 33, but a complex mixture of products precluded their purification and characterization (data not shown). Based on LC-MS analysis of the reaction mixture (see Supplementary Information), minor intermediates 21 and 24 may be extended further by reaction with donors 16 and 14.

Scheme 6.

Other modes of oxygen activation of 2. (A) O1 activation leading to 31 and 32. (B) O5 activation leading to 3.

3. Conclusions

A rapid and efficient chemical method has been developed to prepare short-chain trans-(1 → 2) linked mannopyranosyl oligosaccharides in one step from the self-oligomerization of a mannopyranosyl allyl orthoester (2). The trisaccharide, allyl 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranoside (5) and disaccharide, allyl 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetylα-D-mannopyranoside (4), were obtained in 23% and 56% isolated yields, respectively, and both are useful precursors in chemical syntheses of nested fragments of high-mannose N-glycan 1 [15]. Larger αMan-(1 → 2) linked oligosaccharides (tetra- to hexasaccharides) were also obtained in high purity but lower yields for other synthetic applications.

4. Experimental section

4.1. General methods

All chemicals were purchased as anhydrous reagent grade and were used without further purification, and all reactions were performed under anhydrous conditions unless otherwise noted. Compound 2 was purchased from PracticaChem without further purification. Reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on silica gel precoated aluminum plates. Zones were detected by heat/charring with a p-anisaldehyde–sulfuric acid visualization reagent [15]. Flash column chromatography on silica gel (preparative scale) was performed on the Reveleris® X2 flash chromatography system. 1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra were recorded at 22 °C on a Bruker Avance III HD 500-MHz FT-NMR spectrometer or a Varian DirectDrive 600-MHz FT-NMR spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm (δ) relative to the 1H signal of residual CHCl3 at δ 7.26 ppm and the 13C signal at δ 77.23 ppm. Abbreviations for NMR signal multiplicities are: s = singlet; dd = doublet of doublets; d = doublet; dt = doublet of triplets; t = triplet; td = triplet of doublets; q = quartet; m = multiplet. Two-dimensional NMR spectra were recorded on the same instruments using Bruker or Varian data processing software. Mass spectrometric analyses were performed on a Bruker microTOF-Q II quadrupole time-of-flight (QTOF) mass spectrometer with an ESI source.

4.2. General oligomerization reaction conditions

Under a N2 atmosphere, 3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-1,2-O-(allyloxyethylidene)-β-D-mannopyranose (2) (5.43 g, 14.0 mmol) was dissolved in 40 mL of DCM to give a 0.35 M solution, and 4 Å molecular sieves (5.0 g) were added to the solution. The reaction solution was cooled to 0 °C and 0.03 eq. of TMSOTf was added. The reaction solution was stirred at room temperature overnight and then quenched with a few drops of Et3N. The reaction mixture was vacuum-filtered through a Celite pad, the filtrate was collected and concentrated at 30 °C in vacuo, and the residue was purified by column chromatography to give disaccharide 4 (2.40 g, 3.55 mmol, 51.0%), trisaccharide 5 (0.90 g, 0.93 mmol, 20.1%), tetrasaccharide 6 (0.22 g, 0.18 mmol, 5.0%), and larger oligomers (0.28 g) along with monomer 3 (640 mg, 1.65 mmol, 11.9%) (Scheme 2).

4.3. Analytical data on isolated products

4.3.1. Allyl 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranoside (4)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.90 (m, 1H, OCH2–CH]CH2), 5.41 (dd, J = 3.6, 10.2 Hz, 1H), 5.27–5.37 (m, 5H), 5.19 (dd, J = 10.1, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 5.16 (t, J = 9.9 Hz, 1H), 4.98–4.94 (m, 3H), 4.98 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.94 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.07–4.27 (m, 8H), 3.95 (ddd, J = 9.8, 6.9, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 2.15 (s, 3H), 2.14 (s, 3H), 2.09 (s, 3H), 2.08 (s, 3H), 2.04 (s, 3H), 2.03 (s, 3H), 2.01 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.8, 170.5, 170.4, 169.8, 169.8, 169.7, 169.4( × 2), 133.2, 118.1, 99.5, 99.2, 77.0, 70.4, 69.8, 69.2, 68.6, 68.4, 62.5, 62.2, 21.0 ( × 7). HRMS: (m/z) calcd for C29H40O18Na+ (M +Na)+ 699.2113; found 699.2117.

4.3.2. Allyl 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranoside (5)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.88 (m, 1H, OCH2–CH]CH2), 5.38 (dd, J = 3.6, 10.2 Hz, 1H), 5.22–5.35 (m, 8H), 5.11 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.98 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.94 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.15–4.25 (m, 4H), 4.00–4.18 (m, 10H), 3.94 (ddd, J = 9.8, 6.9, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 2.17 (s, 3H), 2.14 (s, 3H), 2.11 (s, 3H), 2.07 (s, 3H), 2.05 (2s, 6H), 2.03 (s, 3H), 2.02 (s, 3H), 2.01 (s, 3H), 1.99 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.1, 170.8, 170.5, 170.1 ( × 2), 169.8 ( × 2), 169.5( × 2), 169.4, 138.1, 118.2, 99.8, 99.4, 97.5, 77.4, 76.7, 70.5, 69.7, 69.6, 69.5, 69.3, 68.7( × 3), 68.4, 66.3, 66.2, 62.6, 62.2, 62.1, 21.0 ( × 10). HRMS: (m/z) calcd for C41H56O26Na+ (M+Na)+ 987.2959; found 987.2938.

4.3.3. Allyl 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1→2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranoside (6)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.88 (m, 1H, OCH2–CH]CH2), 5.30 (dd, J = 3.6, 10.2 Hz, 1H), 5.14–5.28 (m, 11H), 5.06 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 5.00 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.91 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.88 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 3.94–4.15 (m, 14H), 3.97 (ddd, J = 9.8, 6.9, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 2.06 (s, 3H), 2.03 (s, 3H), 2.02 (2s, 6H), 1.99 (2s, 6H), 1.98 (s, 6H), 1.95 (2s, 6H), 1.94 (s, 6H), 1.93 (2s, 6H), 1.91 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.1, 170.8, 170.7 ( × 2), 170.5, 170.0 ( × 2), 169.5 ( × 2), 169.4 ( × 2), 169.3, 133.1, 118.1, 99.8, 99.6, 99.2, 97.4, 77.0, 76.4, 70.4, 69.8, 69.6, 69.5 ( × 3), 69.2, 68.7, 68.6 ( × 3), 68.4, 66.4, 66.3, 66.2, 66.1, 62.5, 62.1 ( × 3), 21.0 ( × 10). HRMS: (m/z) calcd for C53H72O34Na+ (M+Na)+ 1275.3804; found 1275.3792.

4.3.4. Allyl 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranoside (7)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.82 (m, 1H, OCH2–CH]CH2), 5.31 (dd, J = 3.6, 10.2 Hz, 1H), 5.14–5.28 (m, 14H), 5.09 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 5.06 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 5.05 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.91 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.88 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 3.92–4.15 (m, 17H), 3.87 (ddd, J = 9.8, 6.9, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 2.06 (s, 3H), 2.04 (s, 6H), 2.01 (2s, 6H), 1.99 (s, 3H), 1.98(3s, 15H), 1.97 (s, 3H), 1.95 (s, 3H), 1.94 (3s, 15H), 1.93 (2s, 6H), 1.91 (s, 3H). HRMS: (m/z) calcd for C65H88O42Na+ (M +Na)+ 1563.4650; found 1563.4684.

4.3.5. Allyl 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-Dmannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-Dmannopyranoside (8)

HRMS: (m/z) calcd for C77H104O50Na+ (M+Na)+ 1851.5496; found 1851.5466.

4.3.6. Allyl 2,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-α-D-mannopyranoside (23)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.81 (m, 1H, OCH2–CH]CH2), 5.21, 5.15 (m, 2H, OCH2–CH]CH2), 5.00 (dd, J = 3.6, 1.7 Hz, H-2), 4.99 (dd, J = 10.1, 9.8 Hz, H-4), 4.81 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, H-1), 4.19 (dd, J = 12.2, 5.5 Hz, H-6a), 4.08 (m, 1H, OCH2–CH]CH2), 4.02 (dd, J = 12.2, 2.3 Hz, H-6b), 4.01 (dd, J = 9.8, 3.6 Hz, H-3), 3.93 (m, 1H, OCH2–CH]CH2), 3.84 (ddd, J = 10.1, 5.5, 2.3 Hz, H-5), 2.07 (s, 3H), 2.03 (s, 3H), 2.01 (s, 3H). HRESIMS: (m/z) calcd for C15H22O9Na+ (M +Na)+ 369.1192; found 369.1228.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

AS thanks the National Science Foundation (CHE 1707660), and AS and QP thank the National Institutes of Health (SBIR Contract HHSN261201500020C), for financial support.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carres.2019.107897.

References

- [1].(a) Freudenberg K, Scholz H, Chem. Ber. 63 (1930) 1969–1972; [Google Scholar]; (b) Braun E, Chem. Ber. 63 (1930) 1972–1974; [Google Scholar]; (c) Bott HG, Haworth WN, Hirst EL, J. Chem. Soc. (1930) 1395–1405; [Google Scholar]; (d) Wang W, Kong F, J. Org. Chem. 63 (1998) 5744–5745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].(a) Lemieux RU, Morgan AR, Can. J. Chem. 43 (1965) 2198–2204; [Google Scholar]; (b) Lemieux RU, Hendricks KB, Stick RV, James K, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 97 (1975) 4056–4062; [Google Scholar]; (c) Lemieux RU, Morgan AR, Can. J. Chem. 43 (1965) 2214–2221; [Google Scholar]; (d) Kochetkov NK, Khorlin AJ, Bochkov AF, Tetrahedron 23 (1967) 693–707; [Google Scholar]; (e) Zurabyan SE, Thkhomirov MM, Nesmeyanov VA, Khorlin AY, Carbohydr. Res. 26 (1973) 117–123; [Google Scholar]; (f) Hanessian S, Banoub J, Carbohydr. Res. 44 (1975) C14–C17; [Google Scholar]; (g) Banoub J, Bundle DR, Can. J. Chem. 57 (1979) 2091–2097; [Google Scholar]; (h) Ogawa T, Matsui M, Carbohydr. Res. 51 (1976) C13–C18; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Wulff G, Schmidt W, Carbohydr. Res. 53 (1977) 33–46; [Google Scholar]; (j) Tsui DS, Gorin PAJ, Carbohydr. Res. 144 (1985) 137–147; [Google Scholar]; (k) Matsuoka K, Nishimura S-I, Lee YC, Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 68 (1995) 1715–1720; [Google Scholar]; (l) Uriel C, Ventura J, Gomez AM, Lopez JC, Fraser-Reid B, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012 (2012) 3122–3131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].(a) Kochetkov NK, Khorlin AJ, Bochkov AF, Tetrahedron Lett. 5 (1964) 289–293; [Google Scholar]; (b) Kochetkov NK, Khorlin AJ, Bochkov AF, Tetrahedron 23 (1967) 693–707; [Google Scholar]; (c) Kochetkov NK, Bochkov AF, Snyatkova VJ, Carbohydr. Res. 16 (1971) 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- [4].(a) Kochetkov NK, Tetrahedron 43 (1987) 2389–2436; [Google Scholar]; (b) Ogawa T, Matsui M, Carbohydr. Res. 51 (1976) C13–C18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].(a) Hiranuma S, Kanie O, Wong C-H, Tetrahedron Lett 40 (1999) 6423–6426; [Google Scholar]; (b) Seeberger PH, Eckhardt M, Danishefsky S, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119 (1997) 10064–10072. [Google Scholar]

- [6].(a) Wang W, Kong F, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 38 (1999) 1247–1250; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang W, Kong F, J. Carbohydr. Chem. 18 (1999) 451–460; [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang W, Kong F, Tetrahedron Lett. 39 (1998) 1937–1940; [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhu Y, Kong F, J. Carbohydr. Chem. 19 (2000) 837–848; [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhu Y, Chen L, Kong F, Carbohydr. Res. 337 (2002) 207–215; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Chen L, Zhu Y, Kong F, Carbohydr. Res. 337 (2002) 383–390; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Zhu Y, Kong F, Synlett 12 (2000) 1783–1787. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fowler JS, Ido T, Semin. Nucl. Med. 32 (1) (2002) 6–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].(a) Kumar HMS, Joyasawal S, Reddy BVS, Charkravarthy PP, Krishna AD, Yadav JS, Indian J Chem. B 44B (2005) 1686–1692; [Google Scholar]; (b) Kumar R, Tiwari P, Maulik PR, Misra AK, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006 (2006) 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Plѐ K, Carbohydr. Res. 338 (2003) 1441–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yang Z, Lin W, Yu B, Carbohydr. Res. 329 (2000) 879–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].(a) Fraser-Reid B, Grimme S, Piacenza M, Mach M, Schlueter U, Chemistry 9 (2003) 4687–4692; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jayaprakash KN, Fraser-Reid B, Carbohydr. Res. 342 (2007) 490–498; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Uriel C, Gómez AM, López JC, Fraser-Reid B, Org. Biomol. Chem. 10 (2012) 8361–8370; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Fraser-Reid B, Ganney P, Ramamurty CV, Gómez AM, López JC, Chem. Commun. 49 (2013) 3251–3253; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Uriel C, Ventura J, Gómez A, López JC, Fraser-Reid B, J. Org. Chem. 77 (2012) 795–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lindhorst T, J. Carbohydr. Chem. 16 (1999) 237–243. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Matsuo I, Isomura M, Miyazaki T, Sakakibara T, Ajisaka K, Carbohydr. Res. 305 (1998) 401–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].(a) Liu Y, Chen G, J. Org. Chem. 762 (2011) 8682–8689; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ramos-Soriano J, de la Fuente MC, de la Cruz N, Figueiredo RC, Rojo J, Reina J, Org. Biomol. Chem. 15 (2017) 8877–8882; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Matsuo I, Wada M, Manabe S, Yamaguchi Y, Otake K, Kato K, Ito Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125 (2003) 3402–3403; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Fujikawa K, Seko A, Takeda Y, Ito Y, Chem. Rec. 16 (2016) 35–46; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Jiang R, Liang X, Jin S, Lu H, Dong Y, Wang D, Zhang J, Synthesis 48 (2016) 213–222; [Google Scholar]; (f) Ma Q, Sun S, Meng XB, Li Q, Li S-C, Li Z-J, J. Org. Chem. 76 (2011) 5652–5660; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Ramos-Soriano J, de la Fuente MC, de la Cruz N, Figueiredo RC, Rojo J, Reina JJ, Org. Biomol. Chem. 15 (2017) 8877–8882; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Ogawa T, Yamamoto H, Carbohydr. Res. 102 (1982) 271–283; [Google Scholar]; (i) Pantophlet R, Trattnig N, Murrell S, Lu N, Chau D, Rempel C, Wilson IA, Kosma P, Nat. Commun. 8 (2017) 1601–1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].(a) Zhang W, Pan Q, Serianni AS, J. Label. Comp. Radiopharm. 59 (14) (2016) 673–679; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Meng B, Wang J, Wang Q, Serianni AS, Pan Q, Tetrahedron 73 (2017) 3932–3938; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Meng B, Wang J, Wang Q, Serianni AS, Pan Q, Carbohydr. Res. 467 (2018) 23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Demchenko AV, Other methods for glycoside synthesis, in: Demchenko AV (Ed.), Handbook of Chemical Glycosylation, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2008, pp. 382–412. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.