Abstract

In this report, fluorescent systems consisting of two Rhodamine B moieties were designed and synthesized employing the solid-phase synthetic approach. The compounds were tested for their chemosensing behavior upon the addition of various metal ions over UV–vis absorption and fluorescence spectra. Two probes, 1 and 3, exhibited the best affinity to Sn(IV) ions, resulting in strong fluorescence as well as absorbance enhancement with the low detection limits (2.78 and 2.56 μM, respectively). Compound 3 having two excitations as well as emission maxima was used for the construction of the light dimmer with the alarm for detection of too low pH. The system is operated by a change of pH and can be used as a molecular electronic device.

Introduction

Rhodamine B (RhB) is a widely used fluorescent dye that has found a great deal of interest in many applications, including pH determination,1 redox,2 or metal3,4 sensing. RhB is distinguished due to its good price availability in small as well as higher quantity, chemical stability, photostability, advantageous spectroscopic, mainly fluorescent properties, etc. Therefore, this dye is commonly used in the construction of new probes and sensors solely or in combination with other dyes. This combination, often establishing the FRET effect, enables us to detect some markers or construct a device for molecular electronics.

Fluorescent properties of conjugates between Rhodamine B and other dyes affected by metal ions enabled the construction of various molecular logic gates.5−7 For example, the combination of RhB with indole and naphthalene fluorescent dyes exhibited sequential dual FRET processes used for multiple logic gate operations via the response signals of Fe(III) and Hg(II) ions.5 A combination of Rhodamine B with fluorescein was used for the construction of a “half adder” molecular logic gate in microfluidic devices operated by pH change.6 The change of UV–vis and fluorescence of the RhB-nitrosalicyl derivative in the presence of Cu(II) and Al(III) ions was used for the construction of the YES logic function with an INHIBIT logic gate.7

The fluorophores having two rhodamine moieties in one molecule were used for the detection of metal ions as well. However, the studies are limited mainly to Fe(III)8−11 and Hg(II),12−16 rarely to Cu(II)17,18 ion selectivity. Some of these bis-Rhodamine B dyes were used for the construction of molecular logic gates of the INHIBIT type.8,16,18

Here, we report a study of new bis-Rhodamine B derivatives suitable for the detection of metal ions with increased selectivity to the tetravalent tin. Moreover, our molecules might be suitable for the construction of the light dimmer operated by pH connected with a detector of too low pH value.

Results and Discussion

Solid-Phase Synthesis of Compounds 1–4

The novel chemosensors bearing two Rhodamine B fluorophores 1–4 are depicted in Figure 1. They are composed of the central pyrimidine core enabling substitution in positions 4, 5, and 6 to implement various moieties with, namely, NH groups as typical chelating agents. We chose position 6 for binding of rhodamine dyes via p-phenylenediamine (all probes) and position 5 for binding of other substituents via an amino group (probes 1 and 2) or longer linker (probes 3 and 4). This substitution leads to the systems with rhodamine dyes bound via aliphatic and aromatic amine groups. Furthermore, the 2-(2-ethoxyethoxy)acetic acid moiety was selected as a substituent in position 4 to increase the system solubility. Moreover, we substituted the nitrogen of one rhodamine unit by the methyl group (probes 2 and 4). This alkylation should block the spirolactam cyclization of one rhodamine moiety, assuring to keep fluorescence regardless of the analyte pH. The synthesis is based on the knowledge reported earlier for similar systems with one rhodamine dye.19,20 We extended the reported synthesis for further reaction sequences and bound another rhodamine moiety (Schemes 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Derivatives 1–4 bearing two Rhodamine moieties designed as new chemosensors.

Scheme 1. Solid-Phase Synthesis of Derivatives 1 and 2.

(i) 1-(9H-fluoren-9-yl)-3-oxo-2,7,10-trioxa-4-azadodecan-12-oic acid (PEG), HOBt, DMAP, DIC, DMF/DCM (1:1), rt, 16 h. (ii) 50% piperidine, DMF, rt, 15 min. (iii) 4,6-dichloro-5-nitro-pyrimidine, DIEA, dry DMF, rt, 2 h. (iv) p-phenylenediamine, DIEA, dry DMF, rt, 2 h. (v) Rhodamine B, HOBt, DIC, DMF/DCM (1:1), rt, 16 h. (vi) Na2S2O4, K2CO3, ethyl viologen diiodide, H2O/DCM, rt, 16 h. (vii) 4-nitrobenzenesulfonyl chloride (4-Nos-Cl), 2,6-lutidine, DCM, rt, 16 h. (viii) MeOH, PPh3, DIAD, THF, rt, 0.5 h. (ix) 2-mercaptoethanol, DBU, DMF, rt, 5 min. (x) SnCl2.2H2O, DIEA, DMF, N2, rt, 16 h. (xi) 50% TFA in DCM, rt, 1 h.

Scheme 2. Solid-Phase Synthesis of Derivatives 3 and 4.

(i) 1-(9H-fluoren-9-yl)-3-oxo-2,7,10-trioxa-4-azadodecan-12-oic acid (PEG), HOBt, DMAP, DIC, DMF/DCM (1:1), rt, 16 h. (ii) 50% piperidine, DMF, rt, 15 min. (iii) Rhodamine B, HOBt, DIC, DMF/DCM (1:1), rt, 16 h. (iv) 50% TFA in DCM, rt, 1 h.

Spectral Properties of 1–4

First, probes 1–4 were characterized by UV–vis (Figure S13 to S16) and fluorescence spectroscopy (Table 1). The UV–vis absorption spectra of probes 1 and 3 revealed a very low response of the typical absorption for rhodamine compounds in the range from 500 to 600 nm and so very low molar extinction coefficients (ε = 603 dm3·mol–1·cm–1 for 1 and 3260 dm3·mol–1·cm–1 for probe 3, determined in an EtOH at 560 nm). On the other hand, permanently opened rhodamine moiety of probes 2 and 4 showed evident absorption in the range from 500 to 600 nm and thus a higher molar extinction coefficient (ε = 91,600 and 51,600 dm3·mol–1·cm–1, respectively).

Table 1. Fluorescent Properties of New Probes.

| ex (nm) |

em (nm) |

QYa (%) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | DMSO | H2O | EtOH | MeOH | DMSO | H2O | EtOH | MeOH | DMSO | H2O | EtOH | MeOH |

| 1 | 567 | 555 | 567 | 563 | 590 | 578 | 580 | 583 | 7.7 | 1.3 | 4. 0 | 11.9 |

| 324 | 326 | 491 | 462 | |||||||||

| 2 | 567 | 572 | 568 | 563 | 592 | 597 | 582 | 585 | 1.2 | 8.0 | 2.5 | 10.8 |

| 3 | 567 | 558 | 567 | 563 | 590 | 591 | 580 | 583 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 4.8 | 16.2 |

| 332 | 332 | 489 | 462 | |||||||||

| 4 | 567 | 572 | 566 | 563 | 592 | 597 | 583 | 585 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

QY, fluorescence quantum yield determined at 520 nm with Rhodamine B in DMSO as a reference, according to the previously published protocol.22 In the case of dual emission, the yield is determined for the higher wavelength.

The fluorescence measurements exhibited the typical rhodamine excitation and emission maxima (Table 1), slightly different according to the used solvent (λex = 555–572 nm; λem = 578–597 nm). Interestingly, compounds 1 and 3 exhibited evident excitation/emission maxima at 324–332/462–491 nm, respectively, besides typical rhodamine excitation and emission maxima. Further, we assessed the quantum yields of probes 1–4 in four different solvents (DMSO, H2O, EtOH, and MeOH). This measurement revealed a strong solvent dependence, as shown in Table 1. Very low quantum yields might be explained by the fluorescence quenching produced by the aggregates of the zwitterion and the cationic molecular forms of rhodamine moiety.21

The pH Dependence of Probes 1–4

To investigate the influence of the different pH on the spectra of probes 1–4, we measured the spectroscopic properties in Britton–Robinson buffer (0.05 M) with various pH values (Figure 2). Not surprisingly, all probes showed a pH dependence of fluorescence intensities at pH 2–4, as shown in Figure 2a. While probes 1 and 3 lost almost all emission at around pH 4, their N-methylated analogous 2 and 4 expectedly kept the fluorescence at a significant level above this pH. Further, the pH-dependent variation of absorbance in the rhodamine typical region (around 570 nm) revealed the evident differences between probes 1/3 and 2/4 (Figure 2 and Figures S17 to S20). While the absorbance of 1 and 3 remains very low in the whole range of studied pH, probes 2 and 4 exhibit appreciably increased absorbance in this pH region due to one ring being permanently opened. Moreover, only a slight change of absorbance at 565 nm between acidic and basic pH is observable in all probes (Figure 2 and Figures S17 to S20). These results point to the fact that the pH-mediated opening of the lactame ring in all probes in acidic pH is not so efficient for all the probes, and the equilibrium is shifted to the closed form. This can be caused by stacking, micelle formation, mutual intra/intermolecular interaction, etc.

Figure 2.

(a) pH-dependent variation of fluorescent intensity at an emission wavelength of 583 nm (excitation at 563 nm). (b) pH-dependent variation of absorbance at 565 nm of 1 and 3 (c = 10 μM) measured in Britton–Robinson buffer (0.05 M) with various pH values. (c) pH-dependent variation of absorbance at 565 nm of 2 and 4 (c = 10 μM) measured in Britton–Robinson buffer (0.05 M) with various pH values.

Although both compounds 1 and 3 exhibited two fluorescence excitation and emission maxima (see Table 1), only probe 3 showed a different pH dependence upon a used excitation wavelength (Figure 3). As depicted in Figure 3a, when the excitation wavelength of probe 3 was 563 nm, the maximum fluorescence intensity was reached at pH 2. The emission was still significant at pH 3 but disappeared at pH 4. In higher pH, the system is turned off. On the contrary, probe 3 upon excitation at 325 nm showed that the intensity of the fluorescence peak reached maxima at pH 12. In a range of pH 4–12, the fluorescence intensity is tunable by pH change (Figure 3b). Probe 1 exhibited insignificant changes in fluorescence intensity at excitation at 325 nm.

Figure 3.

Fluorescence intensity dependence of 3 (c = 10 μM) measured in Britton–Robinson buffer (0.05 M) with various pH values at (a) λex = 563 and (b) 325 nm.

Absorption and Fluorescence Titrations of 1–4 with Metal Ions

We further investigated the change of spectral properties of compounds 1–4 after the addition of various cations (Figures 4 to 7). The cations were studied as chlorides or nitrates of Sn(IV), Sn(II), Fe(II), Fe(III), Ca(II), Cd(II), Al(III), Ba(II), Ce(III), K(I), Na(I), Li(I), Hg(II), Zn(II), Cu(I), Cu(II), Mg(II), Ag(I), Pb(II), Cr(III), and Cs(I) ions in a concentration of 50 μM with application of the probes in a concentration of 10 μM.

Figure 4.

(a) Fluorescence emission and (b) UV–vis spectra of 1 (10 μM) in the presence of various metal ions (50 μM) in MeOH/H2O (2:1, v/v).

Figure 7.

Job plots for probes (a) 1 and (b) 3 (in a MeOH/H2O solution (2:1, v/v)) with a total concentration of rhodamine derivatives and Sn(IV) 10–6 M. Absorbance was measured at 560 nm.

The fluorescence spectra of 1 and 3 displayed the very low intensity of characteristic emission band in the range from 500 to 600 nm (in MeOH/H2O (2:1, v/v)). The addition of various metal ions caused a significant increase in the fluorescence intensity with an emission maximum at around 583 nm (Figures 4a and 5a). This observation supported the formation of the complex between 1 or 3 and the ions. The highest emission was observed for Sn(IV) ions for which the fluorescence increased approximately seven times in the case of 1 and thirteen times in the case of 3. The selectivity of 1 and 3 toward tetravalent tin compared to other ions is also obvious from the fluorescence response depicted in Figure 6. The addition of various metal ions to the solution of probes 2 or 4 displayed almost no change in the fluorescence intensity, which indicated clear unsuitability of these compounds as chemosensors for ion determination.

Figure 5.

(a) Fluorescence emission and (b) UV–vis spectra of 3 (10 μM) in the presence of various metal ions (50 μM) in MeOH/H2O (2:1, v/v).

Figure 6.

Selectivity of (a) probes 1 (10 μM) and (b) 3 (10 μM) toward various metal ions (50 μM) in MeOH/H2O (2:1, v/v).

Subsequently, the UV–vis absorption spectra measured for intact compounds 1 and 3 also revealed a very low intensity of the typical absorption for rhodamine compounds in the range from 500 to 600 nm (Figures 4b and 5b). Upon addition of metal ions, the absorption band at 560 nm, indicating the rhodamine spirolactam ring opening, appeared. Its intensity is dependent on the type of metal ions. The highest intensity of absorbance came up upon the addition of Sn(IV), which was accompanied by a remarkable color change (from colorless to pink) and the increasing molar extinction coefficients (ε = 10,758 dm3·mol–1·cm–1 for 1 and 14,560 dm3·mol–1·cm–1 for 3).

A comparison of the fluorescence after the addition of the individual ions is depicted in Figure 6. The most significant increase of the fluorescence was observed after the addition of Sn(IV) ions. Appreciable fluorescence enhancement was also observed after the addition of Al(III), Sn(II), Fe(II), and Fe(III) ions. On the other hand, the fluorescence even decreased when Cs(I) ions were added in the case of probe 3.

Further, to investigate the interaction between our probes and Sn(IV), the fluorescent titration experiments were performed (Figures S21 and S22). The Job plot shows 1:1 stoichiometry between probe 1 and Sn(IV), which indicates the formation of a 1:1 complex (Figure 7a). On the other hand, the stoichiometry of 3 and Sn(IV) indicates the formation of a 3:2 complex (Figure 7b). Moreover, calculations for the binding constant using fluorescence titration data were performed. The association constant for the formation of rhodamine complexes were evaluated using the Benesi–Hildebrand plot,23,24

where I represents the emission intensity at a certain concentration of the metal ion added, Imax represents the maximum emission intensity in the presence of added metal ions, and I0 represents the emission intensity of free probe at 582 nm (λexc = 563 nm). The association constant (K) for binding of Sn4+ ions by 1 and 3 was estimated from the emission titration experiments as 1.57 × 104 and 1.63 × 104 M–1, respectively (Figures S23 and S24). The detection limit of probes 1 and 3 for the Sn(IV) determination was calculated to be 2.78 and 2.56 μM, respectively (Figure S25 and S26), which is comparable with the best-published results (0.9 μM).25

Further, we measured the time course changes in the fluorescence intensity of the complexation between the 1 or 3 probe and Sn(IV). Our results revealed that, while the fluorescence intensity for compound 1 remarkably increased for the first 25 min, the fluorescence intensity for compound 3 was practically constant from the beginning (Figure 8). According to these results, compound 3 is the final one suitable for tin ion sensing.

Figure 8.

Time courses of fluorescence intensity of 1 and 3 upon the addition of Sn(IV) in MeOH/H2O (2:1, v/v) (λext = 563 nm).

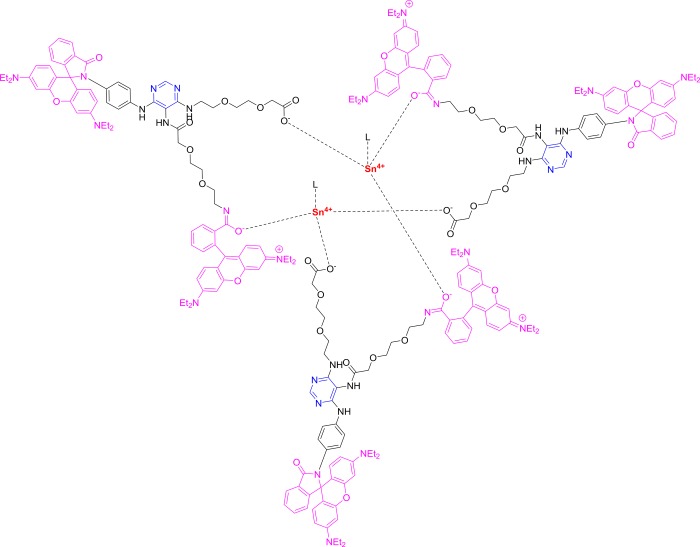

From the molecular structure and spectral results of sensors 1 and 3, a possible sensing mechanism was postulated (Figures 9 and 10). This sensing mechanism based on the Sn(IV)-triggered spirolactam ring-opening process comprises the two carbonyl O atoms as the most likely binding sites for Sn(IV) on compound 1 (Figure 9). On the other hand, the Job plot indicated the 3:2 coordination mode between probe 3 and Sn(IV). These results suggest the proposed interaction mode of 3 and Sn(IV), as shown in Figure 10, where Sn(IV) is coordinated with the three carbonyl oxygen atoms of 3.

Figure 9.

Proposed complexation of Sn(IV) ions and probe 1.

Figure 10.

Proposed complexation of the Sn(IV) ions and probe 3.

As it follows from Figure 3, the variation of the fluorescence intensity with pH altering after excitation at 325 nm can be used for the construction of a light dimmer with emission intensity operated by pH in the range of 4–12. Moreover, when pH decreases under 4, the excitation at 563 nm will afford emission at 590 nm. This fact can be used for the detection/alarm activation of pH lower than 4. Derivative 3 can serve as the molecular electronics device imitating a more complicated classical electronics device depicted in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Scheme of a molecular dimmer operated by pH with the too low pH alarm.

The dimmer itself is operated by two inputs IpH and I325. The first belongs to a circuit constructed by, e.g., a glass electrode, the potential of which is dependent on pH. An appropriate current of variable intensity generated by a combination of the glass electrode and resistor RpH comes into the operational amplifier OA1. The second input I325 is constant and forms an analog of an excitation wavelength of 325 nm used in the case of a molecular device.

The amplifier OA2 has the input I563 of the constant value imitating the excitation of 563 nm when the molecular device is used. The second input is the variable current coming from the pH electrode. The combination of resistors R1 to R3 allows the throughput of the OA2 only if the intensity of the current input corresponds to pH < 4. In such a case, this current will light on the diode emitting at 590 nm.

Conclusions

We have synthesized four fluorescent probes bearing two Rhodamine B moieties in their structure. Two of them, probes 1 and 3, exhibited increased absorbance and evident fluorescence enhancement upon the addition of Sn(IV) ions with a micromolar detection limit that is comparable with the best-published results. Moreover, probe 3 showed pH dependence dual excitation as well as emission maxima (563 and 325 nm) with inverse sensitivity under the different pH values. This property was used for the construction of a molecular dimmer, enabling to tune the light intensity by the change of pH with a detector of too low pH. This system can be used in molecular electronics as a pH guard with an alarm signaling potential damage caused by high acidity.

Experimental Section

Materials and Methods

Solvents and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA) or Fluorochem (UK). The polystyrene resins were purchased from Aapptec (Canada). The synthesis was performed on domino blocks in disposable polypropylene reaction vessels obtained from Torviq (Niles, MI).

All reactions were carried out at room temperature (21 °C) unless stated otherwise. Resin slurry was washed with the appropriate solvent (10 mL per 1 g) by shaking for 1 min. All intermediates were characterized by the LC–MS analysis. For this purpose, a sample of the polymer-bound compound (∼5 mg) was treated with 50% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in dichloromethane (DCM) for 30 min. Residual solvents were evaporated by a stream of nitrogen and residuum extracted into 1 mL of MeOH.

The LC–MS analyses were carried out on the UHPLC–MS system (Waters). This system consists of UHPLC chromatograph ACQUITY with a photodiode array detector and single quadrupole mass spectrometer and uses a XSelect C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm) at 30 °C and a flow rate of 600 μL/min. The mobile phase was (A) 10 mM ammonium acetate in HPLC grade water and (B) HPLC grade acetonitrile. A gradient was formed from 10% A to 80% of B in 2.5 min; kept for 1.5 min. The column was reequilibrated with a 10% solution of B for 1 min. The ESI source was operated at a discharge current of 5 μA, a vaporizer temperature of 350 °C, and a capillary temperature of 200 °C.

Purification was carried out on a C18 reverse-phase column (YMC, 20 × 100 mm for 5 μm particles). The gradient was formed from 10 mM aqueous ammonium acetate and acetonitrile at a flow rate of 15 mL/min. The purity of all compounds after HPLC purification is >95%.

NMR 1H/13C spectra were recorded on a JEOL ECA400II (400 MHz) spectrometer at magnetic field strengths of 9.39 T (with operating frequencies of 399.78 MHz for 1H and 100.53 MHz for 13C). Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in parts per million (ppm), and coupling constants (J) are reported in Hertz (Hz). NMR spectra were recorded at room temperature (21 °C) and were referenced to the residual signals of DMSO-d6. The residual acetate salts exhibited a signal at 1.7–1.9 ppm (1H) and two signals at 173 and 23 ppm (13C).

HRMS analysis was performed on an LC chromatograph (Dionex UltiMate 3000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) with an Exactive Plus Orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) operating in positive scan mode in the range of 1000–1500 m/z. Electrospray was used as a source of ionization. Samples were diluted to a final concentration of 0.1 mg/mL in a solution of water and acetonitrile (50:50, v/v). The samples were injected into the mass spectrometer following HPLC separation on a Phenomenex Gemini column (C18, 50 × 2 mm, 3 μm particle) using an isocratic mobile phase of 0.01 M MeCN/ammonium acetate (80/20) at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min.

Solid-Phase Synthesis of Compounds 1–4

Derivatives 1 and 2 were synthesized according to the procedure depicted in Scheme 1. Derivatives 3 and 4 were synthesized according to the procedure depicted in Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Linker 1 (Acylation with PEG)

The Wang resin (loading 1.0 mmol/g, ∼1 g) was washed three times with DCM. A solution consisting of 1-(9H-fluoren-9-yl)-3-oxo-2,7,10-trioxa-4-azadodecan-12-oic acid (2 mmol), HOBt (2 mmol), DMAP (0.5 mmol), and DIC (2 mmol) in DMF/DCM (1:1, v/v, 10 mL) was added to the resin. The resin slurry was shaken at rt for 16 h. The resin was washed three times with DMF and three times with DCM. Next, the Fmoc protecting group was removed by exposure to 50% piperidine in DMF (v/v, 10 mL) for 15 min, and then, the resin was washed three times with DMF and three times with DCM.

Reaction with 4,6-Dichloro-5-nitropyrimidines (Resin 2)

Resin 1 (∼1 g) was washed three times with dry DMF and reacted with a solution consisting of 4,6-dichloro-5-nitropyrimidines (5 mmol) and DIEA (5 mmol) in dry DMF (10 mL) at rt for 16 h. The resin was washed five times with DMF and three times with DCM.

Reaction with p-Phenylenediamine (Resin 3)

Resin 2 (∼0.5 g) was washed three times with dry DMF and reacted with a solution consisting of p-phenylenediamine (2.5 mmol) and DIEA (2.5 mmol) in dry DMF (5 mL) at rt for 16 h. The resin was washed three times with DMF and three times with DCM.

Acylation with Rhodamine B (Resins 4, 6, 7, 9, 12, and 13)

Resins 3, 5, 8, 10, and 11 (∼0.5 g) were each washed three times with DCM. A solution consisting of Rhodamine B (1.5 mmol), HOBt (1.5 mmol), and DIC (1.5 mmol) in DMF/DCM (1:1, v/v, 5 mL) was added to the resin. The resin slurry was shaken at rt for 16 h. The resin was washed eight times with DMF and eight times with DCM.

Sulfonylation with 4-Nitrobenzenesulfonyl Chloride, Fukuyama–Mitsunobu Reaction with Methanol and Removal of the Nos Group (Resin 7)

Resin 3 (∼250 mg) was washed three times with DCM and three times with DMF. A solution consisting of 4-nitrobenzenesulfonyl chloride (0.75 mmol) and 2,6-lutidine (0.825 mmol) in DCM (2.5 mL) was added to the resin, and the reaction slurry was shaken at rt for 16 h. The resin was washed five times with DCM.

The resin was washed three times with anhydrous THF. A solution consisting of alcohol (0.625 mmol) and PPh3 (0.625 mmol) in anhydrous THF (2.5 mL) was added. The resin was stored in a freezer for 30 min followed by reaction with DIAD (0.625 mmol) at rt for 1 h. The resin was washed three times with THF and five times with DCM.

The resin was washed three times with DMF and was reacted with a solution consisting of 2-mercaptoethanol (0.6 mmol) and 0.2 M DBU (0.2 mmol) in DMF (2.5 mL) for 5 min.

Cleavage from Resin with TFA (Compounds 1–4)

Resins 6, 9, 12, and 13 (∼250 mg) were each treated with 2 mL of a solution consisting of TFA/DCM (1:1, v/v) for 1 h. The cleavage cocktail was collected, and the resin was washed three times with 50% TFA in DCM. The combined extracts were evaporated by a stream of nitrogen, and the crude products were purified by reversed-phase HPLC.

Characterization of Compound 1

Yield 99.2 mg (79%) of pink amorphous powder. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.93–7.88 (m, 1 H), 7.86–7.80 (m, 2 H), 7.75–7.64 (m, 2 H), 7.59–7.47 (m, 2 H), 7.26 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.02–6.97 (m, 1 H), 6.85–6.78 (m, 2 H), 6.66–6.57 (m, 4 H), 6.56–6.49 (m, 2 H), 6.44–6.30 (m, 4 H), 6.29–6.22 (m, 3 H), 6.17–6.06 (m, 2 H), 4.92 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 1 H), 3.88 (s, 2 H), 3.54–3.25 (m, 16 H, overlapped with water), 3.14–3.03 (m, 4 H), 3.03–2.93 (m, 4 H), 1.10–1.02 (m, 18 H), 0.85–0.77 (m, 6 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.1, 166.4, 165.4, 159.3, 156.8, 155.6, 154.3, 154.2, 153.4, 152.0, 149.1, 148.7, 148.6, 148.5, 148.3, 136.9, 132.7, 132.6, 132.2, 130.6, 129.3, 128.5, 128.4, 128.2, 128.1, 128.0, 127.9, 127.5, 125.2, 125.1, 124.1, 123.2, 122.9, 122.3, 120.7, 108.0, 107.8, 106.9, 106.7, 105.8, 105.7, 97.6, 97.4, 97.3, 94.8, 69.5, 69.2, 68.4, 67.7, 67.2, 66.0, 63.6, 43.4, 43.3, 12.1, 11.9. HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C72H79N10O8+ [M + H]+ 1211.6077, found 1211.6090.

Characterization of Compound 2

Yield 83.6 mg (85%) of dark pink amorphous powder. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.93 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.87 (s, 1 H), 7.77–7.53 (m, 5 H), 7.25 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2 H), 6.95–6.83 (m, 7 H), 6.82–6.70 (m, 1 H), 6.65–6.51 (m, 2 H), 6.45–6.32 (m, 3 H), 6.32–6.18 (m, 2 H), 6.15–6.05 (m, 2 H), 4.83–4.75 (m, 1 H), 3.66–3.22 (m, 17 H, overlapped with water), 3.20–3.10 (m, 4 H), 3.03–2.89 (m, 7 H), 2.79–2.68 (m, 1 H), 1.18 (q, J = 6.7 Hz, 12 H), 1.06 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 6 H), 0.78 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 6 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.2, 167.4, 165.6, 159.3, 156.8, 156.7, 156.6, 155.6, 154.9, 154.2, 154.1, 152.4, 149.2, 148.6, 148.4, 137.5, 136.7, 135.6, 132.6, 132.2, 131.3, 131.2, 130.0, 129.6, 129.2, 129.1, 128.5, 128.1, 127.6, 124.6, 124.1, 123.7, 123.0, 120.0, 113.6, 113.5, 112.6, 112.5, 110.8, 108.1, 107.9, 106.9, 106.6, 97.4, 95.6, 95.0, 70.3, 69.5, 69.4, 68.7, 68.3, 67.2, 45.1, 45.0, 43.5, 43.4, 43.2, 12.1, 12.0, 11.9. HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C73H82N10O8+ [M + H]+ 1225.6233, found 1225.6244.

Characterization of Compound 3

Yield 38 mg (47%) of pink amorphous powder. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.74 (br. s., 1 H), 7.94 (s, 1 H), 7.85–7.79 (m, 2 H), 7.73–7.67 (m, 1 H), 7.56–7.48 (m, 2 H), 7.48–7.40 (m, 2 H), 7.27–7.21 (m, 2 H), 7.06–7.02 (m, 1 H), 6.97 (dd, J = 1.6, 5.7 Hz, 1 H), 6.57–6.46 (m, 4 H), 6.38–6.22 (m, 9 H), 6.20 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 2 H), 4.02–3.97 (m, 2 H), 3.91–3.87 (m, 2 H), 3.51–3.43 (m, 8 H), 3.42–3.20 (m, 20 H, overlapped with water), 3.09 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2 H), 2.96 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2 H), 1.06–0.97 (m, 24 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 169.9, 167.0, 166.5, 158.6, 155.3, 155.0, 153.4, 153.2, 152.6, 152.4, 148.4, 148.3, 138.7, 133.1, 132.7, 130.3, 130.2, 128.6, 128.4, 128.3, 128.2, 126.7, 123.9, 123.6, 122.7, 122.3, 120.4, 108.2, 108.1, 105.6, 104.8, 97.2, 96.7, 70.0, 69.9, 69.8, 69.6, 69.3, 69.2, 68.2, 67.0, 66.4, 65.5, 64.0, 62.6, 43.7, 43.6, 12.4. HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C78H90N11O11+ [M + H]+ 1356.6816, found 1356.6810.

Characterization of Compound 4

Yield 59 mg (62%) of dark pink amorphous powder. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.96 (s, 1 H), 7.77–7.69 (m, 2 H), 7.65–7.58 (m, 1 H), 7.58–7.51 (m, 1 H), 7.49–7.40 (m, 3 H), 7.28–7.17 (m, 3 H), 7.01–6.92 (m, 3 H), 6.90–6.74 (m, 4 H), 6.50 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2 H), 6.39–6.22 (m, 8 H), 3.65–3.62 (m, 2 H), 3.58–3.39 (m, 20 H), 3.35–3.00 (m, 14 H, overlapped with water), 2.95 (s, 3 H), 1.16 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 12 H), 1.05 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 12 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 169.5, 167.4, 166.6, 158.1, 156.8, 154.9, 154.8, 154.2, 154.0, 153.0, 152.4, 148.4, 138.8, 136.7, 135.4, 132.2, 131.3, 130.2, 129.9, 129.5, 129.0, 128.9, 127.9, 125.2, 123.2, 121.9, 119.5, 113.7, 112.5, 111.3, 108.1, 105.1, 97.3, 95.6, 70.8, 69.7, 69.6, 69.5, 69.0, 68.9, 66.9, 63.8, 45.0, 43.3, 12.1, 12.0. HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C79H92N11O11+ [M + H]+ 1370.6972, found 1370.6967.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Jiří Mach from Cynological Club Bystrovany for a valuable discussion about electronic systems and the layout of the dimmer used in Figure 11. This work was supported by the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic (project TE02000058) and internal grants of Palacky University (IGA_LF_2019_019 and IGA_PrF_2019_027).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c00218.

Copies of 1H/13C NMR HRMS and UV–vis spectra of compounds 1–4, dependence of absorption on pH for compounds 1–4, fluorescence titration experiments of probes 1 and 3 by Sn(IV) ions, association constant calculation graphs for binding of Sn(IV) ions by compounds 1 and 3, and calculation of detection limit for Sn(IV) determination with the use of probes 1 and 3 (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Cui P.; Jiang X.; Sun J.; Zhang Q.; Gao F. A water-soluble rhodamine B-derived fluorescent probe for pH monitoring and imaging in acidic regions. Methods Appl. Fluoresc. 2017, 5, 024009 10.1088/2050-6120/aa69c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierat R. M.; Thaler B. M. B.; Krämer R. A fluorescent redox sensor with tuneable oxidation potential. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 1457–1459. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.03.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Pradhan T.; Wang F.; Kim J. S.; Yoon J. Fluorescent Chemosensors Based on Spiroring-Opening of Xanthenes and Related Derivatives. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1910–1956. 10.1021/cr200201z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J. W.; Rao B. A.; Son Y.-A. Rhodamine-chloronicotinaldehyde-based ″OFF-ON″ chemosensor for the colorimetric and fluorescent determination of Al3+ ions. Sens. Actuators, B 2015, 208, 75–84. 10.1016/j.snb.2014.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.; Wu X.; Yoon J. A dual FRET based fluorescent probe as a multiple logic system. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 111–113. 10.1039/C4CC08245A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kou S.; Lee H. N.; van Noort D.; Swamy K. M. K.; Kim S. H.; Soh J. H.; Lee K.-M.; Nam S.-W.; Yoon J.; Park S. Fluorescent molecular logic gates using microfluidic devices. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 872–876. 10.1002/anie.200703813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-S.; Angupillai S.; Son Y.-A. A dual chemosensor for both Cu2+ and Al3+: A potential Cu2+ and Al3+ switched YES logic function with an INHIBIT logic gate and a novel solid sensor for detection and extraction of Al3+ ions from aqueous solution. Sens. Actuators, B 2016, 222, 447–458. 10.1016/j.snb.2015.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan F.; Zheng T.; Guo S.; Shi D.; Han Z.; Zhou S.; Chen L. New fluorescence probe for Fe3+ with bis-rhodamine and its application as a molecular logic gate. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2015, 151, 881–887. 10.1016/j.saa.2015.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerasinghe A. J.; Schmiesing C.; Varaganti S.; Ramakrishna G.; Sinn E. Single- and multiphoton turn-on fluorescent Fe3+ sensors based on bis(rhodamine). J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 9413–9419. 10.1021/jp1034568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Hong H.; Han R.; Zhang D.; Ye Y.; Zhao Y.-f. A New bis(rhodamine)-Based Fluorescent Chemosensor for Fe3+. J. Fluoresc. 2012, 22, 789–794. 10.1007/s10895-011-1022-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chereddy N. R.; Suman K.; Korrapati P. S.; Thennarasu S.; Mandal A. B. Design and synthesis of rhodamine based chemosensors for the detection of Fe3+ ions. Dyes Pigm. 2012, 95, 606–613. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2012.05.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.; Rao B. A.; Son Y.-A. A highly selective fluorescent chemosensor for Hg2+ based on a squaraine-bis(rhodamine-B) derivative: Part II. Sens. Actuators, B 2015, 210, 519–532. 10.1016/j.snb.2015.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soh J. H.; Swamy K. M. K.; Kim S. K.; Kim S.; Lee S. H.; Yoon J. Rhodamine urea derivatives as fluorescent chemosensors for Hg2+. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 5966–5969. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.06.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Huang X.-J.; Zhu Z.-J. A reversible Hg(ii)-selective fluorescent chemosensor based on a thioether linked bis-rhodamine. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 24891–24895. 10.1039/c3ra43675f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han R.; Yang X.; Zhang D.; Fan M.; Ye Y.; Zhao Y. A bis(rhodamine)-based highly sensitive and selective fluorescent chemosensor for Hg(II) in aqueous media. New J. Chem. 2012, 36, 1961–1965. 10.1039/c2nj40638a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z.; Tian X.; Chen Y.; Hou J.; Ma J. Rhodamine group modified SBA-15 fluorescent sensor for highly selective detection of Hg2+ and its application as an INHIBIT logic device. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 2227–2233. 10.1039/C2RA21864J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chereddy N. R.; Thennarasu S. Synthesis of a highly selective bis-rhodamine chemosensor for naked-eye detection of Cu2+ ions and its application in bio-imaging. Dyes Pigm. 2011, 91, 378–382. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2011.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z.; Li H.; Guo D.; Liu Y.; Tian Z.; Yan S. A novel piperazine-bis(rhodamine-B)-based chemosensor for highly sensitive and selective naked-eye detection of Cu2+ and its application as an INHIBIT logic device. J. Lumin. 2015, 167, 156–162. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2015.06.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brulikova L.; Okorochenkova Y.; Hlavac J. A solid-phase synthetic approach to pH-independent rhodamine-type fluorophores. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 10437–10443. 10.1039/C6OB01772J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brulikova L.; Krupkova S.; Labora M.; Motyka K.; Hradilova L.; Mistrik M.; Bartek J.; Hlavac J. Synthesis and study of novel pH-independent fluorescent mitochondrial labels based on Rhodamine B. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 23242–23251. 10.1039/C5RA20183G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- López Arbeloa F.; Ruiz Ojeda P.; López Arbeloa I. Fluorescence self-quenching of the molecular forms of Rhodamine B in aqueous and ethanolic solutions. J. Lumin. 1989, 44, 105–112. 10.1016/0022-2313(89)90027-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Würth C.; Grabolle M.; Pauli J.; Spieles M.; Resch-Genger U. Relative and absolute determination of fluorescence quantum yields of transparent samples. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 1535–1550. 10.1038/nprot.2013.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra A. K.; Manna S. K.; Mandal D.; Das Mukhopadhyay C. Highly Sensitive and Selective Rhodamine-Based ″Off-On″ Reversible Chemosensor for Tin (Sn4+) and Imaging in Living Cells. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 10825–10834. 10.1021/ic4007026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benesi H. A.; Hildebrand J. H. A spectrophotometric investigation of the interaction of iodine with aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1949, 71, 2703–2707. 10.1021/ja01176a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J.; Yang E.; Ding P.; Tang J.; Zhang D.; Zhao Y.; Ye Y. Two rhodamine based chemosensors for Sn4+ and the application in living cells. Sens. Actuators, B 2015, 221, 688–693. 10.1016/j.snb.2015.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.