Abstract

During the transition to adulthood, effective and culturally relevant supports are critical for families of youth with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). There is a dearth of documented program development and research on supports for Spanish-speaking Latino families during this life stage. The present work describes the cultural adaptation process of an evidence-based transition program for Latino families of youth with ASD. A model of the actions necessary to meaningfully conduct a cultural adaptation in this context is described. After implementing the culturally adapted program titled Juntos en la Transición with five Spanish-speaking families, parents reported high social validity of the program through surveys and interviews. The cultural adaptation process followed in this work is important for the further development of programs that address the transition needs of Latino youth with ASD and their families. Our impressions may also be useful to those who aim to develop culturally sensitive and ecologically valid multi-family group intervention programs for families from cultural and linguistic minority groups.

Keywords: autism, culture, latino, transition, adaptation, family

The transition to adulthood has long been noted as a period of life marked by significant change, often resulting in prolonged periods of stress (Hall, 1904). The stresses of moving from adolescence into adulthood can be particularly acute for youth with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and their families. Not only do youth with ASD face normative shifts in roles and experiences similar to youth without disabilities (e.g., changes in educational, relational, and occupational domains; Arnett, 2000), but they and their families must also navigate transitions in service systems that are critical sources of support (e.g., going from public school services to adult services; Blacher, 2001). After exiting high school, youth with ASD experience a significant loss of services that is greater than that of their peers with other disabilities, and the loss of services is highest for individuals from minority and low-income backgrounds (Shattuck, Wagner, Narendorf, Sterzing, & Hensley, 2011). Furthermore, many individuals with ASD struggle to find meaningful daytime activities following high school exit. National data suggests that 42% of adults with ASD in their early twenties have never been employed, with even higher rates of chronic unemployment among culturally and linguistically diverse individuals (e.g., 66% of Latinos with ASD; Roux, Shattuck, Rast, Rava, & Anderson, 2015). However, currently there are few empirically-based programs to support individuals with ASD and their families during the transition to adulthood, with no transition intervention studies centered on Latino families to our knowledge. The main purpose of this paper is to describe the cultural adaptation process used to develop a program that addresses this need, called Juntos en la Transición (JET).

Latinos in Transition

For Latino families, factors such as inadequate preventive health care and health insurance, language and cultural barriers, and the lack of proximity to services (Arredondo, Gallardo-Cooper, Delgado-Romero, & Zapata, 2014) may compound the stressors associated with having a transition-aged child with ASD. Pervasive disparities in access to autism services have been well-documented, with trends of later and lower rates of educational and medical ASD diagnoses as well as decreased access to ASD-specific knowledge, interventions, and supports among racial and ethnic minority groups including Latinos (Bernier, Mao, Yen, 2010; Bishop-Fitzpatrick & Kind, 2017; Liptak et al., 2008; Magaña, Lopez, Aguinaga, & Morton, 2013; Mandell & Novak, 2005; Travers, Tincani, & Krezmien, 2011). The interplay of such autism-related service disparities is likely a contributing factor to the observed poorer health and lower levels of education and income among Latino adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities compared to their White counterparts (Magaña, Parish, Morales, Li, & Fujiura, 2016).

Special considerations are often necessary to effectively address disability-related transition needs of families from cultural and linguistic minority groups including Latino families (Trainor, Lindstrom, Simon-Burroughs, Martin, & Sorrells, 2008). For example, culture-related differences in areas including but not limited to disability conceptualization, experiences within the education and health care systems, and cultural expectations for transition age youth often require special attention. A lack of acknowledgement of cultural identity and familial differences in transition planning may further marginalize cultural and linguistic minority youth with disabilities and their families, likely resulting in postsecondary transition plans that are ineffective in addressing individual needs (Trainor, 2005; Trainor et al., 2008; Valenzuela & Martin, 2005).

Past research has helped identify specific concerns and needs among stakeholders for Latino youth with disabilities in the transition process. Rueda, Monzo, Shapiro, Gomez, and Blacher (2005) found that Latina mothers of transition-aged youth with ASD believed that the transition process should be centered around the home and family, as opposed to independence in the greater community. Critical transition-related concerns of these mothers included: the importance of adaptive and social skills, values of family and collectivism, expectations that the mother cares for and makes decisions for children, inaccessibility of information on transition, and lack of supervision outside of the home post high school (Rueda et al., 2005). Other researchers such as Povenmire-Kirk, Lindstrom, and Bullis (2010) have interviewed school and transition professionals as well as Latino youth with disabilities and their families. They identified five categories of barriers for families and their transition-aged youth: language, citizenship concerns, inadequate family-school partnerships, lack of culturally aware practices, limited resources, and biased professional attitudes. Povenmire-Kirk et al. (2010) also found that Latino families had a different perception of independent living for individuals with disabilities than families from the dominant White culture, with a stronger expectation to live with one’s family of origin until marriage. Overall, the body of research on Latino families of youth with ASD suggests a need for culturally relevant evidence-based programs and supports during the transition from adolescence to adulthood. While evidence exists for multi-family group transition programs in general (e.g., DaWalt, Greenberg, & Mailick, 2018), there is a dearth of work examining cultural adaptation or development of such programs to improve outcomes for Latino families in particular and for families from other minority cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

Transitioning Together Program

The original intervention of focus in the current cultural adaptation, Transitioning Together (TT), is an evidence-based program for families of youth with ASD designed to increase parental skills, knowledge, and readiness for supporting their child in the transition to adulthood (Dawalt et al., 2018). Per the TT program design, prior to attending a series of multi-family group sessions, each individual family participates in a joining session during which interventionists build rapport and learn about each family’s unique background, history, social supports, and access to community resources. Next, all families attend eight joint 1.5 hour weekly meetings. These include two simultaneous, separately held sessions: a parent psychoeducation group and a social group session for the youth with ASD. The topics for the eight TT parent sessions are: (1) ASD in adulthood, (2) transition planning, (3) problem solving, (4) family topics, (5) community involvement, (6) achieving goals for independence in adulthood, (7) legal issues, and (8) health and well-being. During the third parent group session, a problem-solving process is presented and practiced; at each subsequent parent group session, a group problem solving activity is held as the final group activity. The youth group is designed to include various fun and meaningful social activities, as well as activities that target specific individualized goals. These goals are self-directed by the youth, and can be either personal or professional in nature.

The original TT program (DaWalt, Greenberg, & Mailick, 2018) was developed, piloted, and evaluated in English, largely with White mothers (i.e., 95% of participating parents were White, 88% were mothers). The program has built-in features that encourage group facilitators to individualize implementation based on individual family needs and interests. Much of the content is either flexible and individualized, or is generally useful for families of youth with ASD in the process of transitioning to adulthood within the context of U.S. laws, communities, and service systems. The content is also relevant to individuals across the autism spectrum whose diagnoses specify all levels of support (i.e., requiring support, substantial support, or very substantial support). Given its flexibility, individualization, and broad relevance within the U.S., TT appears to be a promising start-point for devoloping transition interventions centered on families of youth with the broad diagnosis of ASD who belong to cultural and linguistic minority groups in the U.S.

Why is Cultural Adaptation Important?

While evidence-based interventions for youth with ASD and their families such as TT exist, it is important to ensure that such interventions are thoroughly attuned to the cultural and linguistic backgrounds of their recipients. This critical need is evidenced with meta-analytic findings showing that interventions targeted to a specific cultural group were four times more effective than interventions provided to groups consisting of clients from a variety of cultural backgrounds, and that interventions conducted in clients’ native languages were twice as effective as interventions conducted in English (Griner & Smith, 2006). Family intervention programs must be oriented to the cultural beliefs and attitudes of the groups being served. At times, it will be desired to create programs that are originally grounded in the contexts of minority cultures and languages (e.g., Magaña, Lopez, & Machalicek, 2017). In practice however, this is not always feasible, as existing programs designed for the dominant culture are often the most realistic starting points for programming. For the field to advance toward the goal of offering culturally relevant and linguistically appropriate interventions for families, cultural adaptations of programs that were initially developed for the dominant culture are a crucial part of the process (Castro, Barera, & Holleran Steiker, 2010; Valdez, Abegglen, & Hauser, 2013).

How Is Cultural Adaptation Conducted?

Cultural adaptations systematically combine the best available research-based practices with culture and context to address ecological validity issues while maintaining scientific integrity (Bernal & Domenech Rodríguez, 2012; Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Domenech-Rodriguez & Wieling, 2005). The ecological validity framework (EVF; Bernal, Bonilla, & Bellido, 1995) is used to guide what areas of change should be considered for culturally sensitive interventions and treatments. The eight EVF dimensions that should be targeted to achieve congruence between the intervention and culture of the target population are summarized in Table 1 (Bernal et al., 1995). Researchers have used the EVF in cultural adaptations across many programs and populations, such as: (a) the Parent Management Training-Oregon Model for Latino immigrant families in the U.S. (Parra-Cardona et al., 2017), (b) the Adolescent Coping with Depression Course for group psychotherapy with Haitian American adolescents (Nicolas, Arntz, Hirsch, & Schmiedigen, 2009), and (c) Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for deaf families who communicate with American Sign Language (Day, Costa, Previ, & Caverly, 2018).

Table 1.

Ecological Validity Framework Dimension Definitions

| Dimension | Definition |

|---|---|

| Language | Culturally appropriate verbal and written communication |

| Persons | Family-therapist relationship, interactions, and match |

| Metaphors | Cultural symbols, sayings, and concepts |

| Content | Cultural knowledge, values, customs, and traditions |

| Concepts | Congruence between concepts in treatment and cultural context of families |

| Goals | Treatment goals created within context of family values, customs, and traditions |

| Methods | Manner through which treatment goals are achieved |

| Context | Changing social, political, economic, acculturative, and other contexts of families |

While the EVF provides valuable and widely followed guidance for cultural adaptation dimensions, there is no clear gold standard or consistently used model for how to actually carry out cultural adaptation. Multiple researchers across different prevention and intervention contexts have developed such models, frameworks, and guidelines, but seemingly in isolation and without awareness of one another’s work (Domenech Rodríguez & Bernal, 2012). A review of published models indicates some degree of concurrent validity in that the various cultural adaptation process frameworks share some common concepts and recommendations (Domenech Rodríguez & Bernal, 2012). Specifically, there are similar elements that appear across the following seven different cultural adaptation models that have been proposed: Domenech-Rodríguez and Wieling’s Cultural Adaptation Process Model (CAPM; 2005), Leong and Lee’s Cultural Adaptation Model (CAM; 2006), Barrera and Castro’s (2006) Heuristic Framework combined with Lau (2006)’s Selective and Directive Treatment Adaptation Framework, Whitbeck’s Culturally Specific Prevention model (CSP; 2006), Wingwood & Diclemente’s framework for adapting HIV prevention programs (ADAPT-ITT; 2008), Hwang’s Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy (FMAP; 2009), and Kumpfer, Pinyuchon, Teixeira de Melo, and Whiteside’s (2008) cultural adaptation process for international dissemination of the Strengthening Families Program. The authors of these models and frameworks rarely referenced one another. Each of the following actions are described across at least three and as many as five models, albeit with unique terminologies and within varying broad conceptual frameworks: (a) carefully select an appropriate intervention and assure that it requires adaptation, (b) create a working alliance between program developers and community members, (c) generate knowledge by collaborating with community members and stakeholders, (d) assess needs via formative interview and assessment, (e) review relevant literature on culture-specific knowledge (f) collaborate with program content area experts and review literature on content area, (g) make preliminary iterations and present them to stakeholders for feedback that informs next iterations, (h) train carefully selected staff and test a pilot implementation of the program, and (i) evaluate the adapted program and continue refining it based on ongoing feedback and advances in the field.

Pertinent information for cultural adaptations can also be gathered using cultural consensus modeling with community stakeholders (e.g., parents, teachers, family members, youth, and leaders within a community). Given the diversity and heterogeneity that exists within ethnic, linguistic, and cultural groups including those who fall within the umbrella term of “Latinos,” cultural consensus modeling is a useful method to aggregate responses and assess the extent to which informants share common cultural beliefs (Grinker, et al., 2015; Romney, Weller, Batchelder, 1986). In cultural consensus modeling, procedures such as free-listing, ranking, and pile sorting are often used to determine relevant cultural domains and themes.

Cultural Adaptations with Latino Families of Youth with ASD

While studies have shown the importance of considering cultural diversity and the utility of incorporating cultural components into interventions (Benish, Quintana, & Wampold, 2011; Griner & Smith, 2006; Lau, 2006), to date, only a few evidence-based interventions have been culturally adapted or are culturally derived for Latino families of children with ASD. Further, studies exploring the cultural relevance of interventions for families of youth with ASD have primarily focused on early childhood, not the transition into adulthood (Buzhardt, Rusinko, Heitzman-Powell, Trevino-Maack, & McGarth, 2016; Magaña, Lopez, & Machalicek, 2017).

In meeting the needs of culturally and linguistically diverse families, interventions that are developed with a specific cultural group in mind can address unique cultural needs from onset. One culturally derived intervention focused on Latino families of young children with ASD is Magaña et al.’s (2017) work creating a program specifically for Latina immigrant mothers of children with ASD geared to meaningfully consider their unique needs and barriers in service access. Using the EVF (Bernal et al., 1995) and emphasizing cultural strengths, the authors devised an ecologically valid program that promoted engagement, satisfaction, and empowerment among participants (Magaña et al., 2017). Culturally derived programs like these, as well as cultural adaptations of appropriate existing evidence-based programs are essential steps to providing adequate, accessible, relevant supports and services for culturally and linguistically diverse families of youth with ASD. It is prudent to complete such work across developmental stages, from early childhood to the school age years, the transition to adulthood, and beyond.

Goals of the Present Cultural Adaptation

Below we present our cultural adaptation process as an example that can be followed in other adaptation work. Our work had two primary aims: (a) to identify a methodological process to culturally adapt evidence-based multi-family intervention programs in a manner that maximizes access, relevance, and effectiveness and (b) to apply this methodology to culturally adapt an evidence-based group transition program for Spanish-speaking Latino families of youth with ASD.

Case Study: The Cultural Adaptation of Transitioning Together

Interest from a community-based support and education group for Latino families of youth with ASD inspired a cultural adaptation of the TT program. After reviewing the literature for evidence-based approaches to the cultural adaptation process, we found that the EVF (Bernal et al., 1995) provided critical guidance on what needed to be adapted. In contrast, we combined pertinent stages and guidelines that are suggested in multiple models of how to collect and apply information needed to inform adaptations (Barrera & Castro, 2006; Domenech-Rodríguez & Wieling, 2005; Hwang, 2009; Lau, 2006; Leong & Lee, 2006; Whitbeck, 2006; Wingwood & Diclemente, 2008).

Cultural Adaptation Process

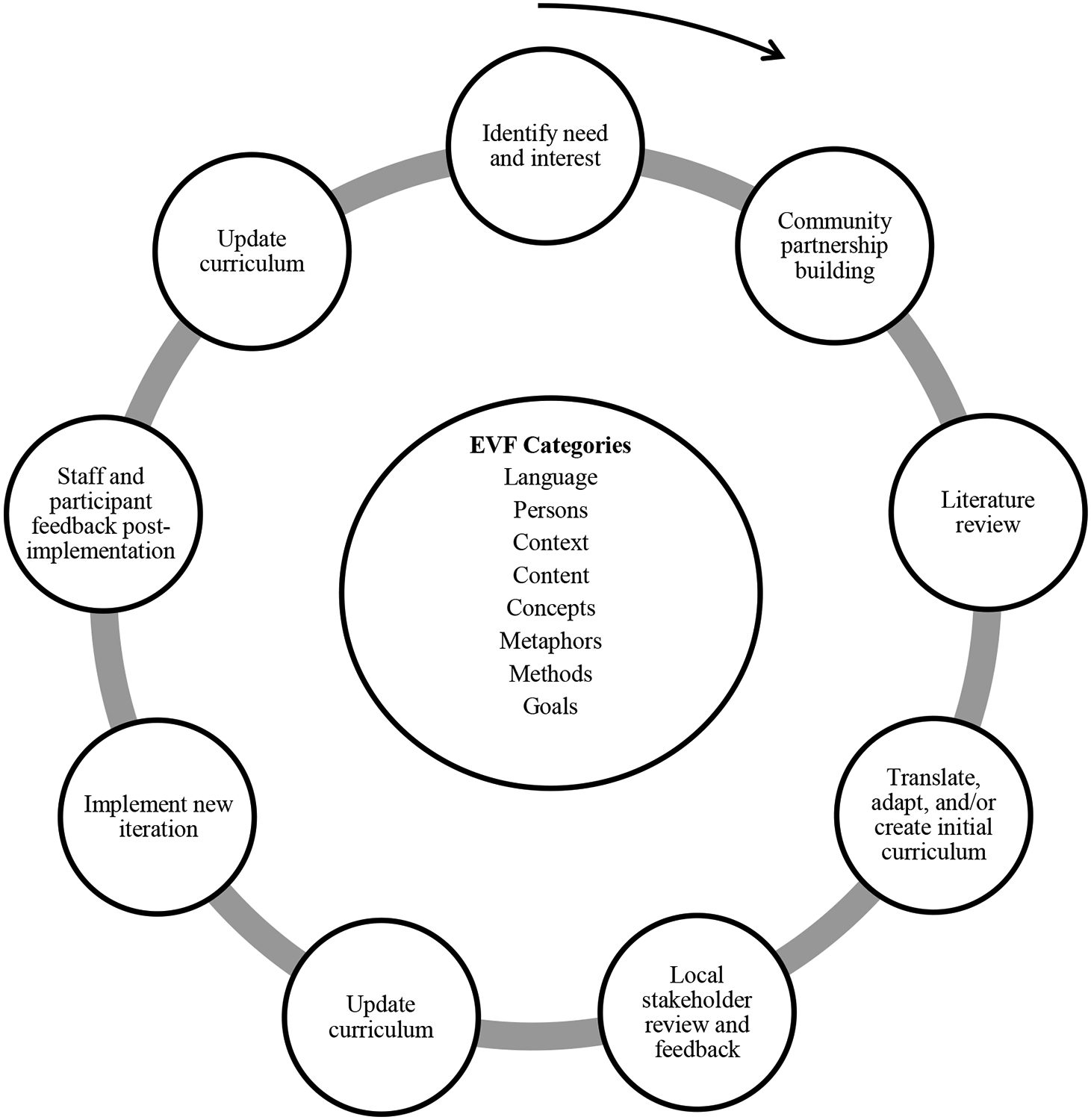

Figure 1 presents the methodological process that we developed and implemented in the cultural adaptation of the TT program. The EVF dimensions for cultural adaptation appear in the model’s center (Bernal et al., 1995). The actions necessary to appropriately inform adaptations of EVF categories appear in nine distinct phases on the outer wheel. It is important to note that the movement through the nine phases began with identification of a local need, and that it was fluid with overlapping phases. Further, the process was iterative and required information from multiple sources.

Figure 1.

Cultural Adaptation Process Including Steps to Inform Adaptations of EVF Categories

We carried out this cultural adaptation in the spirit of cultural consensus modeling (Romney et al., 1986), in that an aggregation of responses from multiple informants within a community were collectively used to inform adaptations. Informants included community leaders, parents, and youth affiliated with a community-based support group; among them, cultural beliefs with common implications for the program were expressed. The actions within each of the nine phases of our process are described in the following paragraphs.

Identify needs and interests.

A vital first step in culturally adapting TT was to learn about the specific interests and needs of the community members who had expressed a desire for implementation of a multi-family transition program in Spanish. Initially, needs and interests were assessed through informal conversations with community leaders. Next, bilingual program developers attended several support group meetings to obtain a better understanding of the community members’ culture, concerns, and current supports. Over time, the program developers were able to learn and gather relevant information regarding cultural aspects and issues for families who regularly attended the support group. Last, formal meetings were held, at which the match between the TT program and community needs were formally discussed, as well as logistics with adding the program to the community’s existing service and resource network.

Community partnership building.

Partnership building between program developers and the community members occurred simultaneously with the identify needs and interests phase, yet served distinct foundational purposes. At formal and informal meetings, the program developers listened and learned about characteristics of the families in the community and openly shared information about themselves and TT. In addition, trust was carefully built during ongoing collaboration between the program developers and the community members.

Literature review.

Research-based findings on beliefs and values that are common among Latino groups were explored (e.g., espiritualismo, familismo, fatalismo, marianismo), as well as the ways in which these factors can impact psychological treatment (e.g., Arredondo et al., 2014). In addition, literature on program content areas was reviewed when making additions and changes to the program content. Further, existing cultural adaptation guidelines within the field were reviewed to ensure that all appropriate considerations were made. Constant reference to the literature allowed for the extant research to inform changes and ongoing processes.

Create or translate and adapt initial curriculum.

Initially, a professional interpretation service was hired to directly translate the TT curriculum to Spanish. It should be noted that this action only applied given the desire to begin with an existing English curriculum. Based on the information collected through the literature review and community partnership building phases, a first round of adaptations was made to the translated Spanish curriculum.

Local stakeholder feedback.

Community stakeholders reviewed information and content from the recent curriculum iteration and provided feedback to program developers during a 2-hour focus group. Nine adult family members of youth with ASD between the ages of 10 and 14 volunteered their opinions regarding utility and acceptability of the program, usefulness of topics covered, absence of necessary topics, and implementation logistics such as timing and location. All participants reported identifying as ethnically Latino and spoke Spanish fluently. The focus group session was recorded with consent of all participants, transcribed, and reviewed for overarching themes relevant to cultural adaptation.

Update program.

Changes to the program were continually made based on specific local stakeholder feedback provided at the focus group, continued conversations with community partners, and ongoing literature review.

Implement new iteration.

The opportunity to organize the delivery of the culturally adapted program to interested families (i.e., mother and/or father and child with ASD) within the partnering community arose. An updated iteration of the curriculum was created based on information collected in all prior phases. Additionally, tips for facilitators geared to increase culturally competent delivery of the program were written. Graduate students and a developmental psychologist from two partnering midwestern universities implemented the program with support from community leaders.

Post-implementation feedback.

Parents completed social validity questionnaires as part of their participation at the end of each group session. Additionally, program developers conducted semi-structured exit interviews to collect additional feedback from parent participants after the entire program ended. The exit interviews included close-ended questions with response options on a Likert scale and open-ended questions. Parents were asked whether they found the program to be beneficial, useful, comprehensible, satisfactory, and unique given prior knowledge, experience, and personal needs. They were asked for critical feedback such as content that may have been irrelevant or inadequately addressed. Last, the program implementers met to share their own opinions on the program’s ecological validity and their reactions to the parents’ feedback.

Update program.

After implementation of the culturally adapted program in this community was complete, the program developers reflected on the information gathered throughout the adaptation process and further adjusted the curriculum for future implementations.

All phases including curriculum updates should continue as the program is delivered to new groups. Now that the cultural adaptation process has resulted in a program that is believed to be ecologically valid for a community of Latino families with youth with ASD (i.e., JET), it will be critical to carry out rigorous research investigating the outcomes of this program with additional communities within the Latino population before then scaling up the intervention to make it more universally available.

Resulting Cultural Adaptations and Pilot Implementation

Adaptations Prior to Implementation

Overall, the Latino family members (i.e., mothers, fathers, and grandparents) of youth with ASD who participated in the focus group had similar concerns to the primarily English-speaking parents who participated in focus groups as part of the original TT program development (Smith, Greenberg, & Mailick, 2012). The Latino focus group participants reaffirmed themes from the initial groups and were strongly interested in all topics from the original TT program, further justifying the use of this English program as a starting point.

Specific needs and preferences were also expressed that required adjustments for the JET program. There was interest in sexual education for the purpose of supporting youth through puberty. Participants also shared a motivation to learn about how to better navigate the service system (e.g., psychiatrists, transportation, assisted living) and address legal issues (e.g., guardianship, special needs trusts, immigration issues). Last, they wished for additional content on how to learn to help their youth plan to meet future educational and vocational goals.

The TT program calls for flexibility in terms of timing and location of group sessions to make attendance as convenient as possible for the families. The original TT program has eight weekly group sessions that last for 1.5 hours, typically during a weeknight evening. Focus group participants expressed concerns about this schedule, as they lived in various neighborhoods across a large city and some parents worked in the evenings. They suggested a major structural change for the program implemented in their community: fewer, but longer sessions held on Saturday afternoons. This would allow families to spend less time commuting to group sessions and to receive more information from each session. Given that the participating families were active members of a monthly support group that took place on Saturday mornings, this also aligned with existing community supports. Although this meant a fewer total number of meetings for this particular group, the families would be able to maintain their connections with one another by continuing to attend the existing support group. Families suggested that JET include an option for a sibling group or for hired caregivers to watch siblings while parents attended. Lastly, it was suggested for the joining session meetings to take place in a location close to each family’s home or, if invited, in their home.

Summary of adaptations.

Feedback from multiple informants across the multiple pre-intervention stages of the cultural adaptation drove changes to the program. First, the program structure was changed to include two topics during each of four sessions that lasted approximately 2.5 hours each. The ordering and grouping of topics were adjusted to include autism in adulthood (i.e., the developmental course of ASD), family topics (i.e., the impact of ASD on family systems and environmental impacts on functioning of individuals with ASD), and problem solving (i.e., introducing and practicing a problem solving method) in the first parent session. The second parent session covered autism in adulthood (i.e., trends for adults with ASD and strategies for behavior management during late adolescence and early adulthood) and community involvement, which consisted of discussions around self-advocacy in the community, community-based activities and social opportunities, and safety concerns. The third parent session covered guardianship and legal issues (i.e., information on long-term planning: guardianship, wills, trusts, immigration issues, etc.) as well as transition planning regarding strategies and services for post-secondary education and employment. The fourth session topics were risks to health and well-being (i.e., risks and protective factors for parental health and well-being) and intimate relationships and sexuality (i.e., issues related to puberty and development of intimate relationship). In addition to structural and content changes, the program materials and facilitator tip manuals were carefully reviewed to assure incorporation of feedback from the multiple sources. The cultural adaptation changes that were made across the EVF dimensions are described in the following paragraphs.

Language.

In the area of language, the curriculum was translated into Spanish and all newly added content was written directly in Spanish. All handouts and communication occurred in Spanish. The language across all materials were also reviewed for comprehensibility by native Spanish-speaking stakeholders.

Persons.

Within the persons dimension, all staff facilitating the parent sessions were bilingual professionals including one native Spanish-speaker. A parent advocate who presented on disability law and education advocacy during the third session was also bilingual in English and Spanish. Additionally, the facilitator tips related to rapport building within culturally competent service delivery were added (e.g., actively listening to individuals to avoid making cultural assumptions).

Context.

The multi-family group sessions were held at a convenient time and location for the families, with more content spread across fewer sessions to reduce burdens related to scheduling and transportation. An option for siblings to come with the rest of the family to group sessions and be appropriately supervised was added. Facilitator tips were edited to include information on the importance of program implementers having familiarity with the community’s culture and values.

Content and Concepts.

To better align with values of familismo, family topics were expanded and moved to the first session. Information and discussion related to immigration was added to the legal issues content and a new topic was added to cover intimate relationships and sexuality. Additionally, aligning values of the program with personalismo, time was set aside for informal gathering and a full meal was provided at each group session.

Metaphors.

Videos and news articles used to exemplify issues and to spark discussion were changed to be sourced from Latino media.

Methods.

The program development and program implementation were flexible to community needs. Community partnerships were carefully fostered and value was placed on strengthening connections between youth with ASD, between parents, and between community stakeholders and program developers.

Goals.

Parents and youth who participated in the program created individualized goals based on their own experiences, needs, and contexts. The problem-solving sessions that occurred at each of the parent sessions focused on discussing and solving problems that parents directly expressed.

Implementation of the Culturally Adapted Program

The culturally adapted TT program, titled JET, was carried out across four sessions at the same local university building where the existing support group community held monthly meetings. Our recruitment goal was to enroll five to eight Latino families of transition-age youth with ASD, and a total of five families participated in the program. Families were defined as one or two primary caregivers (e.g., mother) and their transition-aged child with ASD. At the start of the program, the youth with ASD were an average of 13 years, 6 months. On average, the parents reported first noting concerns of autism symptoms in their child at 18 months and age of ASD diagnosis at 2 years, 10 months. Four of the youth with ASD were males and one was female. All youth with ASD were born in the U.S. Four of the participating parents were born in Mexico and one was born in Colombia. On average, the families had between one and two children in addition to their child with ASD. Of the five participating families, all parents were members of a local Spanish-speaking support group for families of children with ASD, four had previously attended educational workshops related to ASD, three belonged to a church, and two had involved their child with ASD in Special Olympics.

The four JET sessions lasted approximately 2.5 hours each on Saturday afternoons. The parent sessions were conducted in Spanish, facilitated by native and fluent Spanish-speaking professionals. One sibling was welcomed to be in the room with parents and was provided with preferred quiet activities (e.g., coloring). The youth with ASD participated in concurrent social group sessions, which were led by graduate student trainees. The youth social group sessions included activities to promote social participation, collaboration, and communication. Only one of the participating youths was able to complete a youth group satisfaction survey and therefore youth satisfaction surveys were not collated.

Social Validity Findings

Satisfaction Survey.

According to formative post-session satisfaction survey reports, 60% percent of the parents felt very satisfied with the group, while 40% felt satisfied. 100% reported that the materials were easy to understand and that presentation of information was accessible and helpful. Parents often reported a desire for more session time, which may pertain to the large amount of content in each session, and the need for increased access to resources in general.

Post-Program Feedback

Experience with previous transition services and support programs.

Parents generally reported that they had previously received transition-related information from their children’s schools. Some had participated in past workshops offered by local community agencies and parent support groups. They reported that the information provided by these workshops was limited in scope (e.g., education system) and often not available in Spanish; furthermore, these workshops provided little information on services and supports for individuals past age 18. Parents generally found past workshops and information sessions useful, particularly as they related to specific issues (e.g., social stories, challenging behaviors). However, barriers were prevalent in accessing specific resources and care for their child with ASD. For example, the language of previously available workshops deterred one family because of the obstacle of finding an interpreter.

Overall perception of JET program.

Parents reported that they enjoyed participating in the JET program overall, primarily because they felt it provided them with important information on transition. However, they also acknowledged that there was still much left to learn. Two families remarked that they felt additional time was needed for each session to cover more information and to learn more from the other participating families. In terms of benefits, one mother reported that the sessions felt like a “lluvia de ideas” (shower of ideas). Other parents reported feeling assured that their child with ASD could become independent and empowered because they had acquired tools that would help their child in the future. Parents remarked that the JET program increased their awareness of other transition-related issues (e.g., identification card, guardianship) that they had not been aware of prior to their participation. Topics related to guardianship, sexuality, and problem solving were reported to be the most important, with one family reporting that the introduction to ASD was not as important. In terms of benefits for youth with ASD, parents reported that their child with ASD enjoyed attending the teen sessions and felt the sessions provided them with opportunities to practice their social skills.

Recommendations for future programming.

During exit interviews, parents were asked about recommendations on how to improve JET. They reported that given the breadth of issues related to transition, more time should be allotted to cover a greater array of topics. They suggested the inclusion of the following: issues related to different life transitions (e.g., middle school to high school, high school to post-high school), issues that may arise with development (e.g., physical and mental health), and links to agencies and resources for specific needs (e.g., vocational training, therapy, employment). Additionally, parents commented that programming should be offered continuously as needs and priorities may shift throughout the youth’s development and that involving more families and agencies would be beneficial.

Conclusions

The major purpose of this cultural adaptation was to identify and apply a process that adequately addressed what components should be adjusted in the cultural adaptation of an evidence-based multi-family transition intervention program and how to collect the meaningful community feedback necessary to inform those adaptations. See Figure 1 for the stages of the developed cultural adaptation process.

In summary, the process included overlapping actions that are suggested across the cultural adaptation literature (Barrera & Castro, 2006; Domenech-Rodríguez & Wieling, 2005; Hwang, 2009; Kumpfer et al., 2008; Leong & Lee, 2006; Lau, 2006; Whitbeck, 2006; Wingwood & Diclemente, 2008). Completion of these actions led to the collection of information to address each category of the EVF (Bernal et al., 1995). This fluid cycle may continue as additional iterations of this program are tested and additional communities are identified with needs and interests that call for further adaptation. The particular process that we followed per various existing frameworks and models throughout literature may be useful for clinicians and program developers who are culturally adapting other evidence-based caregiver psychoeducation and family group therapy programs.

Overall, application of the present cultural adaptation process led to the successful implementation of a transition program for a community of families with cultural and linguistic backgrounds that differed from those for whom the original program was developed. To our knowledge, no ASD-related transition programs have previously been designed or adapted for cultural or linguistical minority groups. National statistics on Latinos with ASD in their early twenties showed that 71% had never attended any form of postsecondary education, 42% were socially isolated, and 66% had never been employed (Roux et al., 2015), indicating the need for accessible and culturally relevant transition programming.

According to feedback from the Latino families who participated in the culturally adapted JET program, the content and delivery were viewed as acceptable, accessible, and useful overall. Notwithstanding the positive preliminary impressions of the team who piloted JET and the positive feedback from participating families, the clinical outcomes of JET have not yet been evaluated. Conducting a rigorous study on the outcomes of JET with various Latino communities across the U.S. is an essential next step prior to making the JET program more universally available. This is particularly important because of significant heterogeneity within the U.S. Latino population. While Latino family members and stakeholders who participated in the current cultural adaptation appeared to reach consensus regarding needs, values, and attitudes, the adaptations that took place may not be relevant for others who fit under the umbrella term of “Latino.” Cultural beliefs, language preferences, and immigration status of those who participated may have led to changes that would not have been necessary or would have been different in the context of other Latino communities.

Future research centered around testing this more ecologically valid, culturally adapted transition program with Latino families of youth with ASD should systematically evaluate both treatment outcomes and social validity with both youth and parents. These future research directions of the JET program point out an important next step in the field of evidence-based practices for families overall: the need to use rigorous research methods to evaluate the outcomes of culturally adapted programs with families from cultural minority groups. Such research will allow practitioners and policy-makers to better identify what programs work best with whom, and in what contexts. It will also provide clarification around the issue of balancing fidelity to evidence-based intervention implementation with the departure from fidelity that is often necessary when seeking to attain ecological validity.

References

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo P, Gallardo-Cooper M, Delgado-Romero EA, & Zapata AL (2014). Culturally Responsive Counseling with Latinas/os. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association. [Google Scholar]

- Benish SG, Quintana S, & Wampold BE (2011). Culturally adapted psychotherapy and the legitimacy of myth: A direct-comparison meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(3), 279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Bonilla J, & Bellido C (1995). Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: Issues for cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 23, 67–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal GE, & Domenech Rodríguez MM (2012). Cultural adaptations: Tools for evidence-based practice with diverse populations. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bernier R, Mao A, & Yen J (2010). Psychopathology, families, and culture: Autism. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 19(4), 855–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blacher J (2001). Transition to adulthood: Mental retardation, families, and culture. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 106, 173–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32, 582–590. [Google Scholar]

- Buzhardt J, Rusinko L, Heitzman‐Powell L, Trevino-Maack S, & McGrath A (2016). Exploratory evaluation and initial adaptation of a parent training program for Hispanic families of children with Autism. Family Process, 55(1), 107–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, & Holleran Steiker LK (2010). Issues and challenges in design of culturally adapted evidenced-based interventions. Annual Reviews of Clinical Psychology, 6, 213–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DaWalt LS, Greenberg JS, & Mailick MR (2018). Transitioning together: A multi-family group psychoeducation program for adolescents with ASD and their parents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day LA, Costa EA, Previ D, & Caverly C (2018). Adapting Parent–Child Interaction Therapy for Deaf Families That Communicate via American Sign Language: A Formal Adaptation Approach. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 25(1), 7–21. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2017.01.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Domenech-Rodriguez M, & Wieling E (2005). Developing culturally appropriate, evidence-based treatments for interventions with ethnic minority populations In Rastogi M, & Wieling E (Eds.), Voices of color: First-person accounts of ethnic minority therapists (pp. 313–333). Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Domenech Rodríguez MM, & Bernal G (2012). Frameworks, models and guidelines for cultural adaptation In Bernal G & Domenech Rodríguez MM (Eds.), Cultural adaptations: Tools for evidence-based practice with diverse populations (pp. 23–44). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Griner D, & Smith T (2006). Culturally adapted mental health adaptations: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 43, 531–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinker RR, Kang-Yi CD, Ahmann C, Beidas RS, Lagman A, & Mandell DS (2015). Cultural adaptation and translation of outreach materials on Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(8), 2329–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GS (1904). Adolescence: Its psychology and its relations to physiology, anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, religion, and education. New York, NY: Appleton. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang W (2009). The formative method for adapting psychotherapy (FMAP): A community-based developmental approach to culturally adapting therapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(4), 369–377. doi: 10.1037/a0016240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Pinyuchon M, Teixeira de Melo A, & Whiteside HO (2008). Cultural adaptation process for international dissemination of the strengthening families program. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 31(2), 226–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS (2006). Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13, 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Leong FTL, & Lee SH (2006). A cultural accommodation model for cross-cultural psychotherapy: Illustrated with the case of Asian Americans. Special issue: Culture, race, and ethnicity in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 43(4), 410–423. 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liptak GS, Benzoni LB, Mruzek DW, Nolan KW, Thingvoll MA, Wade CM, & Frver GE (2008). Disparities in diagnosis and access to health services for children with autism: Data from the National Survey of Children’s Health. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 29(3), 152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaña S, Lopez K, & Machalicek W (2017). Parents Taking Action: A Psycho-Educational Intervention for Latino Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Family Process, 56(1), 59–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaña S, Lopez K, Aguinaga A, & Morton H (2013). Access to diagnosis and treatment services among Latino children with autism spectrum disorders. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 51, 141–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaña S, Parish S, Morales MA, Li H, & Fujiura G (2016). Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities among People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 54(3), 161–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, & Novak M (2005). The role of culture in families’ treatment decisions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 11(2), 110–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas G, Arntz DL, Hirsch B, & Schmiedigen A (2009). Cultural Adaptation of a Group Treatment for Haitian American Adolescents. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(4), 378–384. 10.1037/a0016307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Cardona JR, Bybee D, Sullivan CM, Rodríguez MMD, Dates B, Tams L, & Bernal G (2017). Examining the Impact of Differential Cultural Adaptation with Latina/o Immigrants Exposed to Adapted Parent Training Interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(1), 58–71. 10.1037/ccp0000160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povenmire-Kirk TC, Lindstrom L, & Bullis M (2010). De escuela a la vida adulta/From school to adult life: Transition needs for Latino youth with disabilities and their families. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 33(1), 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Romney AK, Weller SC, & Batchelder WH (1986). Culture as consensus: A theory of culture and informant accuracy. American Anthropologist 88(2), 313–338. [Google Scholar]

- Roux AM, Shattuck PT, Rast JE, Rava JA, & Anderson KA (2015). National Autism indicators report: Transition into young adulthood. Philadelphia, PA: Life Course Outcomes Research Program, A.J. Drexel Autism Institute, Drexel University; Retrieved from http://drexel.edu/autismoutcomes/publications-and-reports/publications/National-Autism-Indicators-Report-Transition-to-Adulthood/#sthash.V4YjBzEn.dpuf [Google Scholar]

- Rueda R, Monzo L, Shapiro J, Gomez J, & Blacher J (2005). Cultural models of transition: Latina mothers of young adults with developmental disabilities. Exceptional Children, 71(4), 401–414. [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck PT, Wagner M, Narendorf S, Sterzing P, & Hensley M (2011). Post-high school service use among young adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine, 165, 141–146. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LE, Greenberg JS, & Mailick MR (2012). Adults with autism: Outcomes, family effects, and the multi-family group psychoeducation model. Current Psychiatry Reports, 14, :732–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainor AA (2005). Self-determination perceptions and behaviors of diverse students with LD during the transition planning process. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38(3), 233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainor A, Lindstrom L, Simon-Burroughs M, Martin J, & Sorrells A (2008). From marginalized to maximized opportunities for diverse youths with disabilities. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 31(1), 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Travers JC, Tincani M, & Krezmien MP (2011). A multiyear national profile of racial disparity in Autism identification. The Journal of Special Education, 47(1), 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Valdez CR, Abbegglen J, & Hauser CT (2013). Fortalezas familiars program: Building sociocultural and family strengths in Latina women with depression and their families. Family Process, 52, 394–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela R, & Martin J (2005). Self-directed IEP. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 28(1), 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB (2006). Some guiding assumptions and a theoretical model for developing culturally specific preventions with Native American people. Journal of Community Psychology, 34, 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, & Diclemente RJ (2008). The ADAPT-ITT model: A novel method of adapting evidence-based HIV interventions. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 47(Suppl. 1), 40–46. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605df1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]