Abstract

The structure of 30 monosubstituted benzenes in the first excited triplet T1 state was optimized with both unrestricted (U) and restricted open shell (RO) approximations combined with the ωB97XD/aug-cc-pVTZ basis method. The substituents exhibited diverse σ- and π-electron-donating and/or -withdrawing groups. Two different positions of the substituents are observed in the studied compounds in the T1 state: one distorted from the plane and the other coplanar with a quinoidal ring. The majority of the substituents are π-electron donating in the first group while π-electron withdrawing in the second one. Basically, U- and RO-ωB97XD approximations yield concordant results except for the B-substituents and a few of the planar groups. In the T1 state, the studied molecules are not aromatic, yet aromaticity estimated using the HOMA (harmonic oscillator model of aromaticity) index increases from ca. −0.2 to ca. 0.4 with substituent distortion, while in the S1 state, they are only slightly less aromatic than in the ground state (HOMA ≈0.8 vs ≈1.0, respectively). Unexpectedly, the sEDA(T1) and pEDA(T1) substituent effect descriptors do not correlate with analogous parameters for the ground and first excited singlet states. This is because in the T1 state, the geometry of the ring changes dramatically and the sEDA(T1) and pEDA(T1) descriptors do not characterize only the functional group but the entire molecule. Thus, they cannot provide useful scales for the substituents in the T1 states. We found that the spin density in the T1 states is accumulated at the Cipso and Cp atoms, and with the substituent deformation angle, it nonlinearly increases at the former while decreases at the latter. It appeared that the gap between singly unoccupied molecular orbital and singly occupied molecular orbital (SUMO-SOMO) is determined by the change of the SOMO energy because the former is essentially constant. For the nonplanar structures, SOMO correlates with the torsion angle of the substituent and the ground-state pEDA(S0) descriptor of the π-electron-donating substituents ranging from 0.02 to 0.2 e. Finally, shapes of the SOMO-1 instead of SOMO frontier orbitals in the T1 state somehow resemble the highest occupied molecular orbital ones of the S0 and S1 states. For several planar systems, the shape of the U- and RO-density functional theory-calculated SOMO-1 orbitals differs substantially.

1. Introduction

Each of the electronic states of a molecule has a different geometry. However, in general, the higher the state, the lower the certainty to which the molecular structure is known. The ground state of a molecule can be studied using a number of experimental structural methods supported by a lot of reliable computational techniques. The experimental geometry of a short-living excited state species can be indirectly accessible via fast spectroscopy techniques accompanied by computations.1 However, an accurate theoretical description of the excited states requires use of multireference methods instead of single reference ones adequate for the closed-shell ground states.2 Still, a high computational cost of the multireference methods is an obstacle for studying the medium and large-size open-shell molecules, whereas use of the single reference methods to excited states leaves room for uncertainty.3

The first excited triplet state (T1) is the lowest excited state of molecules with the closed-shell configuration in the ground state.4,5 The singlet–triplet transition is spin-forbidden and has low probability. Therefore, the first excited triplet state is predominantly populated via absorption to one of the excited singlet states followed by radiationless electronic and vibrational relaxations and intersystem crossing processes. The triplet state can also be achieved in electron recombination of an ionized molecule, thermal population, excitation by intermolecular energy transfer, and other processes.6,7 The emission from the first excited triplet state (phosphorescence) is spin-forbidden as well, while from the first excited singlet state (fluorescence), it is spin-allowed. Therefore, the lifetime of the former is much longer than that of the latter. Indeed, typical fluorescence lifetimes are 10–6 to 10–3 s1(n → π*) and 10–9 to 10–6 s1(π → π*), whereas for phosphorescence, they are 10–4 to 10–2 s3(n → π*) and 1 to 102 s3(π → π*).8 Utility and applications of phosphorescence stem directly from relatively long T1 lifetimes and the possibility of a high quantum yield even if the transition probability is low.9

Phosphorescence can be applied in emitters in organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs);10,11 solar cells with singlet fission converting a singlet exciton into two triplet excitons conserving spin;12−16 biological sensors and chemical probes based on luminogens with aggregation-induced emission brightened by aggregate formation,17,18 and photodynamic therapy.19−23 However, to develop better devices utilizing phosphorescence, it is necessary to follow well-justified rules rationalizing the design of the phosphorescence maximum, intensity, bandwidth, or radiation lifetime, while conserving the other molecular properties such as bioactivity, bioavailability, sensing ability, technical parameters, and so forth. The introduction of a substituent of known electron donor and/or acceptor properties to a molecule possessing a desired property is an old yet powerful method for the molecular design. The well-founded design could be based on substituent effect descriptors, but can we be sure that the descriptors known so far are adequate for the molecules in the first excited triplet state?

In the case of electronic spectroscopy, the substituent influence on the π-delocalized and σ-skeleton orbitals can be complicated by the effect of the internal heavy atom present in a substituent. A significant heavy atom effect increases probability of the singlet-triplet transitions through spin–orbit coupling and changes the quantum yields and efficiency of radiationless processes.6 Moreover, the states of different symmetry, for example, 3ππ* and 3nπ*, are influenced differently.24,25 Here, we are using density functional theory (DFT) methods inadequate to properly account for spin–orbit coupling. Therefore, hereafter, using the substituent effect, we understand only the substituent influence on the molecular geometry and charge redistribution in the π and σ valence orbitals.

The importance of the substituent effect on the first triplet state is multifold. For example, the triplet state acidities of over fifteen monosubstituted phenols were fairly correlated using ground-state Hammett substituent constants, although they were weaker than those for the first excited singlet state.26 The satisfactory Hammett correlations were found for the triplet decay constants of nine para-substituted benzophenones.27 The electron-donating substituents increased while electron-withdrawing ones decreased the energy of the 3nπ* level. The substituent effect on the triplet state of 4′-substituted 2,4,6-triisopropylbenzophenones was observed, but a regular Hammett plot was shown only for the rate of the triplet-state hydrogen abstraction from o-isopropyl methine of the 2,4,6-triisopropylbenzene moiety.28 The changes were interpreted in terms of substituent hindrance on the rotation around the bond linking the carbonyl group.

Triplet lifetimes of a series of deoxybenzoins allowed to propose the α cleavage mechanism based on the correlation of the rate constant with the Hammett constants and observation that the triplet energy and radiative lifetime remained unaffected by substituents.29 For monosubstituted benzenes, a correlation of the phosphorescence characteristics with the ground-state Hammett constants was not found. In contrast, it existed for fluorescence, and the strongly acting substituents decreased transition energies of fluorescence and phosphorescence.30 On the other hand, linear relationships between both the lowest excited singlet and triplet energy levels, and the triplet decay constants of the parasubstituted phenylanilines and pirydineanilines were obtained, yet based only on 3 to 7 substituted derivatives.31 Quenching of emission spectra of substituted flavanones and the Hammett correlations enabled authors to propose mechanisms of competing photochemical processes in and to assign the relative nπ* and ππ* contributions in the T1 states.32

The nπ* triplet-state energies of ca. 60 substituted aroyls (acetophenones, benzaldehydes, benzophenones, and anthraquinones) were found to be increased by the electron-donating substituents while decreased by the electron-withdrawing substituents, and, except for anthraquinones, they were satisfactorily correlated with the Hammett constants.33 The triplet states of halogenated biphenyls were significantly changed only for the ortho-substituents, which affected the rings twisting dependent on electronegativity and/or polarizability of the halogen.34 However, no relationship with substituent effect descriptors was considered. For a series of biradicals composed of two para-substituted phenyls connected by a substituted cyclopentane ring, the singlet state appeared to be their ground state, regardless of the substituent character.35 For the symmetrical diradicals, the singlet–triplet gap increased with the substituent π-electron-donating ability, yet the gap was large even for asymmetrical ones with one π-electron-accepting substituent.

The time-resolved phosphorescence emission decays of the Me-, Cl-, F-, and OMe-substituted 9,10-phenanthrenequinones enabled plotting the Hammett correlations showing that the singlet and triplet energies increased with the electron-donating ability of the substituent.36 The lifetimes of a series of substituted naphthalenes in the higher triplet excited states significantly correlated with the Hammett constants.37 Unexpectedly, a more significant substituent effect was observed for the second, rather than the first, triplet state. Hammett’s plot for phenol hydrogen abstraction with α-diketones in the nπ* triplet state indicated that the phenol substituent influenced the intercarbonyl dihedral angle, and thus tuned transient state electrophilicity.38

Recently, a lot of studies on triplet states are devoted to metal complexes. The phosphorescence spectra of a series of Pt–acetylide complexes with ligands substituted with a wide range of different functional groups depended strongly on spin density distribution in the triplet exciton.39 However, no regular trends with the triplet state properties were shown. A bell-like Hammett’s plot was obtained for the ruthenium bipyridine complex, in which phosphorescence was quenched using para-substituted phenols in a bimolecular process.40 The unusual plot shape originated from two quenching mechanisms: a phenolate to Ru(II) electron transfer (pKa ≪ pH) and a proton-coupled electron transfer (pKa > pH) when protonated phenol predominates. The kinetics of proton removal from water by 5-substituted NH2, OMe, H, Cl, Br, and CN quinolines have been recently studied using ultrafast transient absorption spectroscopy.41 The mechanism and kinetics of the proton capture appeared to be highly sensitive to the substituent. The proton transfer within the singlet manifold was complicated by an intersystem crossing and proton capture by the triplet states. Nevertheless, the proton capture times showed no correlation with the Hammett constants, which was attributed to the high density of excited singlet and triplet states sensitive not solely to a substituent but also to the solvent and hydrogen bonding. Emission of eight Pt-complexes with substituted 2-phenylbenzimidazole and acetylacetonate ligands has recently been attributed to a mixed triplet ligand-centered and metal-to-ligand-charge-transfer (3LC-MLCT) state.42 For absorption and emission spectra, significant correlations with redox potentials and the Hammett constants have been obtained.

In all the abovementioned investigations of substituted molecules in the triplet state, the triplet state energies, acidities, lifetimes, kinetic parameters of reactions, interactions, singlet-triplet gaps, and so forth, were correlated with the ground-state Hammett substituent effect constants. Perhaps, then, are the ground-state substituent effect descriptors adequate for studying the triplet state behavior? However, those correlations were usually obtained for less than 10 substituents, and even if 60 compounds were examined,33 the regressions were carried out for smaller homogeneous groups of structures. For the first excited singlet state, the special excited-state substituent descriptors were proposed: σCCex by the Cao research group,43−50 cSAR(ex) by Sadlej-Sosnowska and Kijak,51 and sEDA(S1) and pEDA(S1) by us.52 In contrast, as far as we know, no dedicated substituent effect descriptors were constructed for the molecules in the first excited triplet state.

In the last decade, we introduced a series of the substituent and heteroatom incorporation effect descriptors starting from the sEDA and pEDA descriptors of the classical substituent effect,53 through the heteroatom or heteroatomic group incorporation effect sEDA(II) and pEDA(II) descriptors,54 the sEDA(=) and pEDA(=) descriptors of the substitution through the double bond,55 the sEDA(III) and pEDA(III) descriptors of the heteroatom incorporation effect into the ring-junction position,56 and sEDA(S1) and pEDA(S1) for the molecules in the first excited singlet state.52 The sEDA and pEDA descriptors have very clear physical meanings: they show the amount of electrons shifted to, or withdrawn from, the σ and π valence orbitals of the core molecule by the substituent or heteroatomic group. They are calculated based on the natural bond orbital (NBO) method,57 as a difference in population of σ(sEDA) and π(pEDA) valence orbitals on the C atoms of the substituted and unsubstituted benzene rings.53

The sEDA(S1) and pEDA(S1) descriptors demonstrated that for a certain group of substituents, the ground-state descriptors adequately describe the substituent effect in the first excited singlet S1 state. For another group, the analogous description is fair, but there are numerous visible deviations. Finally, there is also a group of substituents for which a large difference between descriptors in S0 and S1 exists. The situation is reflected in the HOMO(S0) and HOMO(S1) orbitals of the ground and the first excited singlet states, respectively. For the first group, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) orbitals are almost identical, for the second, they are fairly similar, while for the last group, they are totally different.

The aim of this paper has been threefold: to optimize structures of 30 monosubstituted benzenes in the T1 state using the ωB97XD/aug-cc-pVTZ level and the unrestricted (U) and restricted open shell (RO) approximations to find geometrical characteristics for a relatively large set of substituents exhibiting diverse σ- and π-electron-donating and/or -withdrawing effects; to construct the sEDA(T1) and pEDA(T1) descriptors for the monosubstituted benzenes in the T1 state and to evaluate their usefulness in characterization of this state; and to observe changes of some T1 state parameters (e.g., aromaticity, spin redistribution, and frontier orbitals energy) with the change of the substituent.

2. Methods

Over 30 monosubstituted benzenes in the first triplet states were considered. The functional groups used covered a wide range of effects on both σ and π valence electron systems of benzenes in the ground and first excited singlet states.52,53 The structures were optimized using the unrestricted (U)58,59 and restricted open shell (RO)60,61 approximations. The ωB97XD62 DFT functional was combined with the aug-cc-pVTZ basis set,63,64 and the Gaussian 09 suite of programs in Revision D1 was applied.65 The harmonic frequencies of all reported systems were positive, and the structures were true minima on potential energy surfaces (PESs). Electron and spin populations were estimated using the NBO approach,57 as implemented in Gaussian 09. Correlation analysis was done using the SigmaPlot 13 program.66

High computational cost of the multireference methods for medium size open-shell molecules, and the semi-quantitative aim of the study, prompted us to use the single reference DFT methods to study the triplet states. However, we decided to mutually verify validity of the RO-DFT and U-DFT predictions for the exited triplet state.67,68 The U-DFT calculations are much faster than the RO-DFT ones, but the former may produce significant spin contamination, while the latter are free from this error. In the unrestricted calculations, the spatial parts of α and β spin orbitals are allowed to differ, and the artificial mixing of different spin states (spin contamination) provides wavefunctions which are not eigenfunctions of the total spin operator. The spin annihilation procedure reduces the size of the error in the unrestricted calculations, then the expectation value of the total spin ⟨S2⟩ is close to S(S + 1). On the other hand, the RO calculations produce no spin contamination and give good wavefunctions and total energies, but the singly occupied orbital energies do not rigorously obey Koopman’s theorem.

The ωB97XD functional used here contains the dispersion correction by definition.62 It includes the exact Hartree–Fock exchange in both short- and long-range and is effective in dealing with charge-transfer states.69,70 For noncovalent systems, ωB97X-D performed slightly better, while it performed much better for covalent systems and kinetics than many other dispersion-corrected functionals.71 It was also found that in the ωB97 family of functional, it was the most accurate for the excited-state calculations.70,72 In our previous study of the substituent effect in the first excited singlet state,52 we considered the ωB97XD functional together with the B3LYP with and without the D3 Grimme’s correction for dispersion forces and CAM-B3LYP. However, in the article, we presented results using only the ωB97XD functional because for many benzene derivatives, it exhibited similar performance to the others but, in general, it produced the least number of doubtful results.52

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Geometry

The monosubstituted benzenes in the ground singlet S0 state are planar,53 and, in the first excited singlet S1 state are, at most, slightly distorted.52 According to both U- and RO-ωB97XD/aug-cc-pVTZ calculations, in the T1 states, the structures of monosubstituted benzenes are split into two groups, both of nearly the CS symmetry. In one of them, the substituent is tilted from the ring plane, the symmetry plane is perpendicular to the ring and includes the Cipso–R bond. In the other, the substituent remains in the quinoid-like ring plain. The τ(CmCoCipsoR) dihedral angles show clear distinction of the groups as τ < 180 deg for the first group and τ ≈ 180 for the second (Table S1).

In the T1 states, already, the geometrical changes show that the substituent effect must be different from those in the S0 and S1 states. Indeed, pyramidization of the Cipso atom, in the BF2, BH2, B(OH)2, Br, CF3, CH3, Cl, CONH2, F, H, Li, MeSO2, NH2, OH, OMe, SH, SiH3, SMe, and tBu-benzene derivatives (Table S1), denotes that in the T1 state, this very atom takes sp3 hybridization. In turn, the π-electron-donating or -withdrawing substituent effects are less-pronounced because of inefficient overlapping of the pz orbitals in the nonplanar ring. On the other hand, the quinoid-like π-electron structure of the ring, in the CCH, CFO, CHO, CN, COCH3, COOH, NC, NMe2, NO2, and Ph benzene derivatives, forces the Cipso–R bond to become more doubled and two Cortho–Cipso bonds to become more single. Rarely, structurally close substituents, such as CONH2 and COOH, CHO, or COCH3, belong to different groups (Figure 1). This is due to the increase of a double bond character of the (O=)C–NH2 bond in the amide group, and in consequence, increase of single bond character between the phenyl ring and the substituent which induce slight piramidization of the Cipso atom. Such an effect is absent for substitution with the COOH, CHO, or COCH3 groups. Thus, instead of the classical substituent effect through the single bond, we basically deal with the substituent effect through a double bond. Increase in the double bond character of the Cipso–R bond decreases ring π-electron delocalization because it enforces the bond length alteration. However, the substituent effect on the ring σ-skeleton, that is, the functional group electronegativity,52−56 is a short-range effect which is not significantly perturbed by local structure deformations. It is really very similar in the substituted methane and benzene.53

Figure 1.

Two types of the monosubstituted benzenes predicted for the first excited triplet state (the U- and RO-ωB97XD/aug-cc-pVTZ calculations). The two kinds of structures exhibit a symmetry plane containing the C–R bond and (A) perpendicular to the ring, (B) coplanar with the ring.

The quinoid-like deformation of the benzene moiety complements the picture of the changes in the T1 state. The ring’s double to single bond lengths ratio could be a fair measure of the ring’s quinoidization degree. However, instead of introducing a new parameter, we use the harmonic oscillator model of aromaticity (HOMA) index,73−75 which was shown to be not only a measure of geometrical aromaticity but also a simple structural descriptor of molecules—be they aromatic or nonaromatic, cyclic or acyclic, or linear or branched.76−78 Moreover, it was already successfully used to study diphenylfulvenes in the first excited triplet state.79 Fulvenes are antiaromatic in the ground singlet but aromatic in the T1 state. Sadlej-Sosnowska demonstrated an increase of the HOMA aromaticity index when fulvenes change their electronic state from S0 to T1. This occurs even if the changes in the number of π electrons accompanied to the S0 → T1 transition are too small to sufficiently explain aromaticity variation (a matter of 0.1e).79 Unlike fulvenes, benzenes are aromatic in S0 and anti-aromatic in the T1 state.80−83 This stems from Baird’s rule which says that in the lowest triplet excited state, the 4n π-electron rings display the aromatic character, while the 4n + 2 ones display the antiaromatic character.80

The HOMA geometrical aromaticity index is calculated based only on the CC ring bond lengths. The benzene CC bond length is the internal standard of perfect aromaticity.73−78 The more different from benzene (HOMA = 1.0) and the more unequal and alternating the bonds are, the lower the HOMA index and the less geometrically aromatic the ring is. HOMA is expressed as follows

| 1 |

where Ri and Ropt stand for the i-th bond length in the analyzed ring and the reference benzene ring (1.3963 Å at the ωB97XD/aug-cc-pVTZ level), respectively, n is the number of the CC bonds in the ring, and α = 257.7 Å–2 is a normalization factor, making the unitless HOMA = 1 for perfectly aromatic benzene and HOMA = 0 for a perfectly alternating hypothetical nonaromatic Kekulé cyclohexatriene ring.

The HOMA geometrical aromaticity indices of the monosubstituted benzenes in the ground S0, the first excited singlet S1, and the first excited triplet states T1 were obtained based on structures optimized using the ωB97XD, TD-ωB97XD, and U-ωB97XD and RO-ωB97XD functionals combined with the aug-cc-pVTZ basis set (Figure 2a and Table S2). They show that the studied benzene derivatives are geometrically aromatic in the ground state (HOMA ≈ 1, black points, Figure 2a), visibly less aromatic in the S1 state (HOMA ≈ 0.8, blue points, Figure 2a) and either nonaromatic or slightly antiaromatic in the T1 state (HOMA ≈ 0.0 ± 0.4, green (U-DFT) and red points (RO-DFT), Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

(a) Variation of the HOMA aromaticity indices of the monosubstituted benzenes in the ground (black), first excited singlet (blue), and first excited triplet states (red and green) (S0, S1, and T1, respectively) calculated using the aug-cc-pVTZ basis set and the ωB97XD, TD-ωB97XD, and U-ωB97XD and RO-ωB97XD method, respectively. (b) Increase of the HOMA aromaticity index of the nonplanar derivatives in the T1 state with the substituent deformation angle.

However, for four exceptions (CHO, COCH3, Na, and NO2), HOMA(T1) approaches 1.0 (Figure 2a, Table S2). The situation is clear for the Na derivative: the Na atom relocates over the flat aromatic C6H5 plane. Similar holds true for Li, but this time, C6H5 is deformed, antiquinoid,82 and thus, HOMA approaches 0.4. The U- and RO-ωB97XD calculations predict CHO and COCH3 derivatives in the T1 states to be planar and aromatic (Figure 2a), which is in agreement with the previous TD-ωB97XD/6-31G** calculations70 and the more accurate multiconfigurational CASSCF/, CIPT2/, and CASPT2/cc-pVDZ calculations.84 Also, the CASSCF calculations demonstrated the NO2 group in T1 nitrobenzene to be slightly pyrimidized but attached to a planar,85 quinoidal ring.86 The biphenyl molecule exhibits HOMA(T1) greater than that of most of the monosubstituted benzenes (Figure 2a). Biphenyl in the T1 state is planar, and the rings are connected by a short inter-ring C=C bond, forcing a quinoid-like, nonaromatic distribution of the π-electron charge (SAC-CI and TD-PBE0 calculations).87 Thus, the π-electrons are delocalized over the para positions, preventing the system from higher quinolidization and loss of aromaticity. Surprisingly, HOMA ≈ 0.4 is also predicted for quite nonplanar bromobenzene. We see the reason for this in a noteworthy increase of the C–Br distance from 1.897 Å (S0) to 1.976 Å (T1) (RO-ωB97XD/aug-cc-pVTZ) and low Br electronegativity. These factors facilitate π-electron delocalization and increase aromatization of the bromobenzene ring in the T1 state. Electronegativity of chlorine is higher, and the analogous increase of the C–Cl distance is smaller [from 1.744 Å (S0) to 1.780 Å (T1)]. Thus, for chlorobenzene in the T1 state, HOMA decreases to ca. 0.2. For similar reasons, aromaticity of fluorobenzene in the T1 state is even lower (HOMA ≈ 0.1, Figure 2a).

Inhomogeneity of the HOMA(T1) values reveals a systematic, exponential trend with respect to the substituent deformation angle if the planar and metal benzene derivatives are omitted (Figure 2b). The trend is the same irrespective of whether the RO- or U-DFT approximation is used. Furthermore, it can also be seen that several other parameters of the benzene monoderivatives which are nonplanar in the T1 state depend on the substituent deformation angle.

At the end of this section, let us mention that even in the structure and aromaticity of the unsubstituted benzene in the T1 state, there is still chaos. This is probably due to symmetry constrains (D6h88−91 or D2h(92)) assumed for T1 benzene at advanced levels of calculations. The constrains accelerate expensive calculations but bias the results when postulated inaccurately. The computational level applied here cannot be used to calibrate advanced multiconfigurational calculations, but it allowed us to perform unconstrained calculations to determine harmonic frequencies in the T1 state and to obtain structures at the local minima on PESs. Interestingly, for the most stable benzene in the T1 state, our U- and RO-ωB97XD/aug-cc-pVTZ calculations concordantly indicated quinoid CS, instead of the quinoid D2h or D6h symmetry structure. In the CS structure, one CH moiety is distorted from the plane much more than the para-positioned CH moiety. However, a definitive verification of whether such a structure is correct or not is beyond the frame of this study.

3.2. sEDA(T1) and pEDA(T1) Descriptors

The sEDA(T1) and pEDA(T1) substituent effect descriptors (Table 1) can be defined in full analogy to the parent sEDA and pEDA descriptors for the substituent effect in the ground state53

|

2 |

where σi and πi denote σ or π valence electron populations at the i-th carbon atom in the phenyl ring of monosubstituted benzene in the T1 state, and superscript ref denotes the respective values in the reference unsubstituted benzene in the T1 state.

Table 1. sEDA and pEDA Substituent Effect Descriptors Calculated for Monosubstituted Benzenes in the Ground,52 First Excited Singlet,52 and First Excited Triplet State Calculated Based on the R-DFT, TD-DFT, RO-DFT and U-DFT Methods, the ωB97XD Functional, and the aug-cc-pVTZ Basis Set.

| S0 |

S1 |

T1 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-ωB97XD |

TD-ωB97XD |

RO-ωB97XD |

U-ωB97XD |

|||||

| substituent | sEDA(S0) | pEDA(S0) | sEDA(S1) | pEDA(S1) | sEDA(T1) | pEDA(T1) | sEDA(T1) | pEDA(T1) |

| BF2 | 0.153 | –0.065 | 0.127 | –0.030 | 0.262 | –0.242 | 0.175 | –0.150 |

| BH2 | 0.162 | –0.115 | 0.142 | –0.090 | 0.286 | –0.392 | 0.208 | –0.310 |

| B(OH)2 | 0.102 | –0.049 | 0.121 | –0.053 | 0.174 | –0.167 | 0.105 | –0.095 |

| Br | –0.174 | 0.051 | –0.148 | 0.060 | 0.139 | –0.279 | 0.153 | –0.293 |

| CCH | –0.175 | –0.011 | –0.166 | –0.011 | –0.061 | –0.084 | –0.049 | –0.099 |

| CF3 | –0.146 | –0.019 | –0.137 | –0.023 | –0.045 | –0.133 | –0.034 | –0.144 |

| CFO | –0.093 | –0.069 | –0.099 | –0.071 | 0.065 | –0.363 | –0.098 | 0.141 |

| CH3 | –0.218 | 0.013 | –0.207 | 0.016 | –0.111 | –0.083 | –0.095 | –0.097 |

| CHO | –0.097 | –0.075 | –0.095 | –0.103 | –0.068 | 0.036 | –0.055 | 0.021 |

| Cl | –0.251 | 0.057 | –0.229 | 0.066 | 0.092 | –0.275 | 0.108 | –0.293 |

| CN | –0.153 | –0.032 | –0.145 | –0.035 | –0.038 | –0.160 | –0.025 | –0.171 |

| COCH3 | –0.108 | –0.061 | –0.105 | –0.093 | –0.082 | 0.064 | –0.066 | 0.048 |

| CONH2 | –0.128 | –0.038 | –0.095 | –0.115 | –0.038 | –0.188 | –0.044 | –0.182 |

| COOH | –0.110 | –0.059 | –0.104 | –0.101 | 0.044 | –0.340 | –0.127 | 0.181 |

| F | –0.580 | 0.065 | –0.573 | 0.070 | –0.063 | –0.454 | –0.037 | –0.482 |

| H | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Li | 0.537 | –0.009 | 0.482 | –0.007 | –0.030 | 0.692 | –0.017 | 0.682 |

| MeSO2 | 0.006 | –0.017 | 0.024 | –0.019 | 0.086 | –0.086 | 0.094 | –0.098 |

| Na | 0.497 | –0.004 | 0.016 | –0.097 | 0.031 | –0.115 | ||

| NC | –0.390 | 0.004 | –0.366 | 0.010 | –0.264 | –0.135 | –0.248 | –0.158 |

| NH2 | –0.417 | 0.129 | –0.428 | 0.169 | –0.153 | –0.051 | –0.109 | –0.095 |

| NMe2 | –0.443 | 0.162 | –0.432 | 0.171 | –0.358 | 0.189 | –0.344 | 0.175 |

| NO2 | –0.297 | –0.056 | –0.308 | –0.111 | –0.199 | –0.061 | –0.187 | –0.074 |

| OH | –0.517 | 0.106 | –0.513 | 0.117 | –0.096 | –0.280 | –0.062 | –0.316 |

| OMe | –0.520 | 0.110 | –0.517 | 0.122 | –0.110 | –0.273 | –0.070 | –0.316 |

| Ph | –0.214 | –0.001 | –0.224 | –0.002 | –0.077 | –0.099 | –0.064 | –0.115 |

| SH | –0.139 | 0.084 | –0.104 | 0.114 | 0.105 | –0.045 | 0.125 | –0.068 |

| SiH3 | 0.184 | –0.014 | 0.209 | –0.013 | 0.076 | 0.140 | 0.072 | 0.146 |

| SMe | –0.127 | 0.097 | –0.108 | 0.115 | 0.112 | –0.006 | 0.136 | –0.034 |

| tBu | –0.222 | 0.006 | –0.214 | 0.008 | –0.139 | –0.067 | –0.125 | –0.083 |

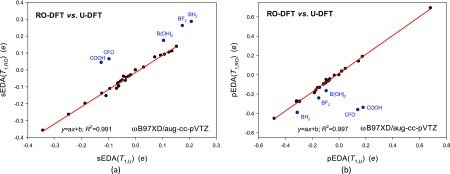

The correlations between the U-DFT or RO-DFT determined that EDA descriptors for the first triplet state are linear (Figure 3). The straight lines demonstrate that for monosubstituted benzenes in the T1 state, the U and RO approximations show essentially the same electron donor–acceptor shifts between the substituent and the phenyl ring. However, the determined descriptors deviate from the straight lines for the following five substituents: BH2, BF2, B(OH)2, CFO, and COOH (Figure 3). The deviations reveal possible limitations of approximations (or only one of them) when a substituent is attached through the B-atom or when it is coplanar with the ring. In the case of the BH2, BF2, and B(OH)2 groups, the differences result from a fairly different substituent tilt from the plane predicted using the U-DFT and RO-DFT methods (Table S1). The U-ωB97XD/aug-cc-pVTZ approximation suggests larger distortion than the RO-ωB97XD/aug-cc-pVTZ one. Why, out of many planar structures in the T1 state, only CFO and COOH deviate from the straight lines becomes clear after inspection of the frontier orbitals.

Figure 3.

Linear correlations between substituent effect descriptors calculated using the U-DFT and RO-DFT methods (ωB97XD/aug-cc-pVTZ level) for monosubstituted benzenes in the first excited triplet states: (a) sEDA(T1) and (b) pEDA(T1). Points in blue were excluded from correlations.

Unexpectedly, unlike for the S0 and S1 states,52 there are no correlations between the EDA(T1) descriptors and those of the S0 states nor the S0 ones (Figure S1). This is due to substituent distortion, ring quinoidization, and concordant charge (spin) redistribution in the T1 state. Indeed, the distortion and quinoidization are basically absent in the planar, or nearly planar, S0 and S1 states, and those states show dependence neither on the substituent deformation angle nor on geometrical aromaticity of the ring.93−95 However, for selected substituents, there are some linear trends between sEDA(T1) and sEDA or sEDA(S1) (Figure S1). This is because the substituent effect on the σ-skeleton, expressed by the sEDA type of descriptors, is a short-range effect. The closest surrounding of some substituents changes only a little, and the effects in the triplet and singlet states are somewhat similar. However, for the long-range effects through the π-electron system, expressed by the pEDA type of descriptors, no correlations are observed (Figure S1).

On the other hand, doubt arises over whether the construction of the sEDA(T1) and pEDA(T1) is correct at all. Let us look again at the ground-state sEDA(S0) and pEDA(S0) descriptors. They are based on the assumption that the σ- and π-valence orbital separation and the NBO approximation are correct. However, there exists another silent assumption about the invariability of the monosubstituted benzene geometry: in the C6H5R structure, the σ- and π-valence orbital charge redistribution does not disturb the geometry of the C6H5 moiety. This is why the sEDA(S0) and pEDA(S0) scales can selectively reflect the substituent properties. As we already demonstrated (Figures 1 and 2; Tables S1 and S2), such an assumption cannot hold true for the triplet T1 states. Indeed, if for series of R substituents, both moieties of the C6H5R molecules simultaneously undergo remarkable changes and additionally split into two types: planar and nonplanar. Then, even though the sEDA(T1) and pEDA(T1) descriptors display the σ- and π-charge redistribution over the C6H5 and R moieties for each particular molecule, they cannot form a homogeneous series of descriptors for an entire group of compounds. In conclusion, it appears that the sEDA(T1) and pEDA(T1) descriptors are probably useless in analyzing larger series of the compounds in the T1 states.

3.3. NBO-Calculated Spin Populations

The NBO approach allows for justification of σ–π valence electron separation. However, within the same approximation, we can question the spin distribution over the valence σ- and π-orbitals. Indeed, it appeared that the τav(CmCoCipsoR) correlates with the spin populations localized at the σ- and π-orbitals of the ring C-atoms of the nonplanar monosubstituted benzenes in the T1 state (Figure 4a and Table S3). As a result, if the planar structures are omitted, the greater the substituent distortion from the ring plane, the greater is the spin population localized at the σ-skeleton and the smaller the spin population localized at the π-electron structure is (Figure 4a). Similar holds true for the HOMA index of the monosubstituted benzene in the T1 state. However, the trends are weaker, and their shapes are different (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

(a) Correlations between the τav(CmCoCipsoR) torsion angle and the spin populations localized at the σ- and π-orbitals of the ring C-atoms of the nonplanar monosubstituted benzenes in the T1 state. (b) Correlations between the HOMA aromaticity index and the spin populations localized at the σ- and π-orbitals of the ring C-atoms of the nonplanar monosubstituted benzenes in the T1 state. The planar systems are omitted in the correlations.

However, distribution of the spin density in the molecules in the T1 states, without partitioning it over the valence σ- and π-orbitals, displays even more essential characteristics. It turns out that in the nonplanar derivatives, the spin density at the phenyl C-atoms is accumulated at the Cipso and Cp atoms, whereas at the other ring C-atoms, it varies erratically (Figure 5a, Table S4). Moreover, the spin densities gathered at single Cipso and Cp atoms show that the former nonlinearly increases, while the latter nonlinearly decreases, with the substituent deformation angle (Figure 5b). Also, the sum of the spin densities at the Co and Cm atoms nonlinearly increases with the substituent deformation angle (Figure 5b). It is to be noted that despite the spin density provided by U- and RO-DFT approximations being slightly different, the qualitative agreement in spin densities obtained with two approximations is excellent (Figure S2), and the U-DFT calculated variation with the deformation angle (Figure S3) is analogous to that presented in Figure 5a.

Figure 5.

(a) Correlation between the RO-DFT calculated spin density at the phenyl ring of the nonplanar monosubstituted benzenes at the T1 state and the sum of spin densities accumulated at the Cipso and Cp atoms. (b) Correlations between the substituent deformation angle and the spin densities accumulated in the Cipso (black) and Cp atoms (red) and cumulated on the sum of ortho and meta C-atoms of the ring in the nonplanar monosubstituted benzenes in the T1 state.

3.4. Frontier Molecular Orbitals

Recently, we have demonstrated that the correlation between the EDA substituent effect descriptors in the S0 and S1 states is very good when the HOMO(S0) and HOMO(S1) orbitals are very similar and show an almost perfect antisymmetry against the benzene plane.50 When the HOMO orbital antisymmetry in one of the states is either perturbed or changed, the correlation deviates slightly, and when one of the two HOMO states has the σ-character, the correlation deviates remarkably. Also, we have shown that the energies and the gap of the frontier orbitals in the two states are linearly correlated with the pEDA(S1) descriptor.

The geometries of the monosubstituted benzenes in the singlet and triplet states are so different that similar relationships between the frontier molecular orbitals in these states cannot be expected. Nevertheless, the juxtaposition of the HOMO orbital shapes of the monosubstituted benzenes in the ground S0 and first excited S1 states, and SOMO in the first excited T1 triplet states calculated with the RO- and U-ωB97XD/aug-cc-pVTZ methods is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Juxtaposition of the HOMO Orbital Shapes of the Monosubstituted Benzenes, XC6H5, in the Ground S0 and First Excited S1 States and the First Excited T1 Triplet States Calculated with the RO- and U-ωB97XD/aug-cc-pVTZ Methodsa.

HSOMO and HSOMO-1 are the highest and the second highest SOMO in the first excited T1 triplet states, respectively.

First, the HSOMO orbitals calculated using RO- and U-DFT approximations are relatively similar (Table 2). A pattern repeating over the benzene plane shows four components with two diagonal nodal lines passing through ortho1 and meta2, and the ortho2 and meta1 C-atoms (Table 2). Additional orbital components are set on substituents, and the entire picture undergoes perturbations related to the structure nonplanarity and substituent asymmetry.

Second, the HSOMO-1 orbitals differ from the HSOMO ones. Furthermore, the HSOMO-1 orbitals in BF2, BH2, B(OH)2, and CFO obtained using the RO-DFT approach, over the benzene plane, exhibit a nodal line perpendicular to the X–Cipso bond between the ortho and meta C-atoms, while those calculated using the U-DFT method exhibit a nodal line containing the X–Cipso bond (Table 2). The SOMO-1 orbitals in dimethylaniline, NMe2, are dissimilar in a slightly different manner: the nodal line is passing diagonally through ortho2 and meta1 C-atoms in the RO-DFT approximation, while it is between the ortho and meta C-atoms in the U-DFT. Even more surprising pictures are seen for the CHO, COCH3, CONH2, COOH, and NO2 derivatives. In the CONH2 and COOH substituted benzenes, the HSOMO-1 obtained with the RO-DFT method has the character of the π-orbitals and those obtained with the U-DFT method have characteristics of the σ-ones, whereas the opposite is the case for the CHO, COCH3, and NO2 groups (Table 2). For the other derivatives, the HSOMO-1 orbitals, calculated within RO- and U-DFT approximations, are relatively similar (Table 2).

Third, if the number of nodal lines over the benzene plane is accepted as a (topological) criterion of orbital similarity, the HOMO orbitals in the S0 and S1 states are topologically more similar to the HSOMO-1 than to the HSOMO orbitals. The former has one nodal line, while the HSOMO orbitals exhibit two such lines. However, the resemblance of HOMO and HSOMO-1 orbitals of Br, CCH, CH3, Cl, CN, F, H, Li, NC, NH2, OH, OMe, Ph, SH, SiH3, SMe, and tBu derivatives, is still weaker than that between the HOMO orbitals in the singlet S0 and S1 states (Table 1). Therefore, if overall correlations between the substituent effect descriptors for the S0 and S1 states were not very strong,52 it is not surprising that for T1 states, it is weaker if it even exists.

Now, let us focus on the energy of the two highest SOMO, the two lowest singly unoccupied molecular orbital (LSUMO), and the gaps between them (Table S5). It is to be noted that the LSUMO–HSOMO and LSUMO+1–HSOMO–1 gaps change because of linear change of the HSOMO and HSOMO–1 energies, while energies of the LSUMO and LSUMO+1 states remain almost unchanged: the slope of the linear change is ca. 0.06 (Figure 6a). As before, the energy of the frontier SOMO and SUMO orbitals of the nonplanar compounds in the T1 state exhibits significant nonlinear, asymmetric parabola-like (a one-extremum asymmetric function) correlations with the τav(CmCoCipsoR)-averaged torsion angle of the substituent (Figure 6b). The direction of the trend for dihedral angles greater than −160° is opposite to that of dihedral angles greater than −130° (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

(a) Relationship between the SUMO–SOMO gap calculated at the RO-ωB97XD/aug-cc-pVTZ level and component SOMO and SUMO energies. Correlations between the SOMO, SUMO, and SUMO–SOMO gap energies (eV) for the monosubstituted benzenes in the T1 state; (b) τav(CmCoCipsoR)—the averaged torsion angle of the substituent; (c) ground-state pEDA(S0) substituent effect descriptor in the range from −0.1 to 0.04 e; and (d) in the range from 0.02 to 0.2 e. Correlations in (b) and (c) are approximate, that is, in (b) ignore the planar structures and some deviating points, and in (c) ignore BH2, COCH3, NO2, and NC substituents. In the correlations (d), no substituent was omitted. (e) Correlation between the ground-state pEDA(S0) and (e) the averaged torsion angle of the substituent, and (f) HOMA index in the T1 state. The red points in (e) correspond to planar structures and were omitted in correlation. The light blue HOMA(S1) points were omitted in correlation presented in (f).

Surprisingly, there are correlations between the HSOMO, HSOMO–1, GAP1 = LSUMO–HSOMO, and GAP2 = LSUMO+1–HSOMO–1 energies in the T1 state and the pEDA(S0) substituent effect descriptor for the ground state (Figure 6c,d). The overall trend for the HSOMO and HSOMO–1 energies increases from the most π-electron-withdrawing BH2, CHO, CFO, and so forth (Figure 6c) to the most π-electron-donating OMe, NH2, and NMe2 groups (Figure 6d). However, for substituents with pEDA(S0) lower than 0.02 e (Figure 6c), a waving can also be seen, whereas for pEDA(S0) higher than 0.05 e, the increasing trend is smooth (Figure 6d). The decreasing trends for the GAP1 and GAP2 are direct consequences of relative resistance of the LSUMO and LSUMO+1 energy on the substituent (Figure 6a).

Additionally, it is observed that τav(CmCoCipsoR) of the nonplanar T1 structures significantly correlates with pEDA(S0), if four deviating substituents (Li, Na, BH2, and NMe2) are ignored (Figure 6e). The asymmetric parabola correlation function has its maximum at pEDA(S0) ≈ 0.04 e (Figure 6e). Thus, the energy of SOMO levels and the GAPs correlate similarly with τav(CmCoCipsoR) and pEDA(S0) because these two parameters correlate with each other as well.

Moreover, the HOMA(S0), HOMA(S1), and HOMA(T1) indices also correlate with the pEDA(S0) descriptor. A quadratic correlation (R2 = 0.625) is observed for HOMA(S0); a significant linear correlation (R2 = 0.750) is present for HOMA(S1), if some derivatives (substituted by π-electron withdrawing groups) are omitted; and a significant, combined linear–exponential correlation, can be found for HOMA(T1) of derivatives substituted by the π-electron donating groups with pEDA(S0) > 0.04 e (Figure 6f). A more imaginative look at the HOMA(T1) graph could lead to a supposition that there is a maximum peak or even a vertical asymptote for pEDA(S0) ≈ 0.02 e (Figure 6f). However, a larger number of substituents with pEDA(S0) ≈ 0.02 e have to be considered to verify such a hypothesis.

Furthermore, the NBO-calculated spin populations at the benzene C-atoms, the nonplanar derivatives, also correlate with the pEDA(S0) descriptor (Figure 7a). In a similar way, cubic correlations can be found between differences in zero point energies (ZPE) of monosubstituted benzenes in the T1 and the pEDA(S0) descriptor: significant for S1 and the difference between the T1 and S1 states (R2 = 0.912 and 0.874, respectively), and kind of a trend for the T1 state (Figure 7b). It is to be observed that, for the nonplanar monosubstituted benzenes, the strongly π-electron-withdrawing and strongly π-electron-donating groups decrease the ZPE difference in comparison to neutrally acting substituents with pEDA(S0) ≈ 0.0 e (Figure 7b). Finally, it is to be noted that U-calculated ZPEs follow the same correlations as RO-ones because they correlate linearly with them (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

(a) Nonlinear correlations between NBO-calculated spin population at ring’s C-atoms. Points for BH2, CCH, CFO, CHO, CN, COCH3, CONH2, COOH, Li, Na, NC, NO2, and Ph substituents were omitted. (b) Cubic correlations between difference in ZPEs of monosubstituted benzenes in the T1 and S1 states and the S0 state, as well as difference between ZPE of the T1 and S1 states and the pEDA(S1) descriptor.

4. Conclusions

Understanding the rules governing the substituent effect in the first triplet state is important because of various applications of molecules in the triplet state, for example, as emitters in OLEDs, solar cells, biological and chemical sensors, and photodynamic therapy. It is known that usually the triplet state geometry is remarkably different than that of the ground or excited singlet states; nevertheless, the ground-state substituent effect descriptors were used to describe properties of the first excited singlet state. Sometimes, they were satisfactory and sometimes they were not. However, to improve the devices reliability on the first excited state properties, it would be worth constructing parameters describing the studied state directly.

To construct parameters based directly on the first excited triplet T1 state structures, we optimized 30 monosubstituted benzene derivatives in the T1 state with unrestricted and RO methods, namely, U-ωB97XD/aug-cc-pVTZ and RO-ωB97XD/aug-cc-pVTZ. Activity of the substituents BF2, BH2, B(OH)2, Br, CCH, CF3, CFO, CH3, CHO, Cl, CN, COCH3, CONH2, COOH, F, H, Li, MeSO2, Na, NC, NH2, NMe2, NO2, OH, OMe, Ph, SH, SiH3, SMe, and tBu, covered a large spectrum of the σ- and π-electron-donating and/or -withdrawing effects. It is to be noted that a substituent can be simultaneously σ-electron-withdrawing and π-electron-donating and so forth.

The optimized structures in the T1 state split into two groups: nonplanar with the substituent distorted from the plane, in the plane perpendicular to the ring, and the planar with the substituent coplanar with the quinoidal ring. In most of the former systems, the substituent is π-electron-donating, while in most of the latter, it is π-electron-withdrawing. The U- and RO-ωB97XD approximations provide concordant results except for boron substituents and a few other groups. It appeared that these differences are reflected in the SOMO-1 (the second highest SOMOs) shapes calculated with the two methods. Surprisingly, the shapes of the SOMO-1 are somehow similar to the HOMO ones of the S0 and S1 states, while SOMO are not. Geometrical aromaticity of the monosubstituted benzenes in the T1 state is significantly depleted in comparison to the S1 and S0 states: HOMA(T1) ≈ −0.2 ÷ 0.4, while HOMA(S1) ≈ 0.8 and HOMA(S0) ≈ 1.0.

The sEDA(T1) and pEDA(T1) substituent effect descriptors for the T1 state were constructed in full analogy to the sEDA(S1) and pEDA(S1) and sEDA(S0) and pEDA(S0) substituent effect for the first excited and the ground singlet states. However, the T1 state descriptors correlate with neither those of the first excited nor those of the ground singlet states. We came to the conclusion that this is because in the T1 state, both the substituent and the ring change dramatically, whereas in the S1 and S0 states, one can assume that, in the first approximation, the ring geometry remains unperturbed and only the σ- and π-electrons shift between the substituent and the ring. Therefore, the sEDA(T1) and pEDA(T1) descriptors do not specifically characterize the functional group, and they cannot provide useful scales for analyses of the T1 states.

We found that the spin density in the T1 states is accumulated at the Cipso and Cp atoms and nonlinearly correlates with the substituent deformation angle: it increases at the Cipso while decreasing at the Cp atom. The SUMO–SOMO gap changes in line with the SOMO energy because energy of the SUMO is basically constant. For the nonplanar T1 structures, the SOMO energy correlates with the substituent deformation angle and the ground state pEDA(S0) descriptor of π-electron-donating substituents for pEDA in the range from 0.02 to 0.2 e.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Medicines Institute statutory founds for 2018 and 2019. The computational grant from the Świerk Computing Centre (CIŚ) is gratefully acknowledged. The author thanks Klaudia Cooper for her help in English language correction.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c00712.

Selected excited-state properties, total Gibbs free, and frontier orbital energies of the studied molecules, plots of correlations of minor importance, and tables with XYZ coordinates of the structures in the T1 state (PDF)

XYZ coordinates of the first excited triplet state of monosubstituted benzenes (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hoffmann R. Geometry Changes in Excited States. Pure Appl. Chem. 1970, 24, 567–584. 10.1351/pac197024030567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lischka H.; Nachtigallová D.; Aquino A. J. A.; Szalay P. G.; Plasser F.; Machado F. B. C.; Barbatti M. Multireference Approaches for Excited States of Molecules. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 7293–7361. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marian C. M.; Heil A.; Kleinschmidt M. The DFT/MRCI method. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2019, 9, e1394 10.1002/wcms.1394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis G. N.; Kasha M. Phosphorescence and the Triplet State. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1944, 66, 2100–2116. 10.1021/ja01240a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasha M. Phosphorescence and the rôle of the triplet state in the electronic excitation of complex molecules. Chem. Rev. 1947, 41, 401–419. 10.1021/cr60129a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lower S. K.; El-Sayed M. A. The Triplet State and Molecular Electronic Processes in Organic Molecules. Chem. Rev. 1966, 66, 199–241. 10.1021/cr60240a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T. Fluorescence and Phosphorescence from Higher Excited States of Organic Molecules. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 4541–4568. 10.1021/cr200166m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle B.Principles and Applications of Photochemistry; Wiley, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kasha M. The triplet state: An example of G. N. Lewis’ research style. J. Chem. Educ. 1984, 61, 204–215. 10.1021/ed061p204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yersin H.; Rausch A. F.; Czerwieniec R.; Hofbeck T.; Fischer T. The triplet state of organo-transition metal compounds. Triplet harvesting and singlet harvesting for efficient OLEDs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 2622–2652. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarma M.; Tsai W.-L.; Lee W.-K.; Chi Y.; Wu C.-C.; Liu S.-H.; Chou P.-T.; Wong K.-T. Anomalously Long-Lasting Blue PhOLED Featuring Phenyl-Pyrimidine Cyclometalated Iridium Emitter. Chem 2017, 3, 461–476. 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Rachford T. N.; Castellano F. N. Photon upconversion based on sensitized triplet–triplet annihilation. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2010, 254, 2560–2573. 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies D.; Schmidt T. W.; Frazer L. Photochemical Upconversion Theory: Importance of Triplet Energy Levels and Triplet Quenching. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2019, 12, 024023. 10.1103/physrevapplied.12.024023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tabernig S. W.; Daiber B.; Wang T.; Ehrler B. Enhancing silicon solar cells with singlet fission: the case for Förster resonant energy transfer using a quantum dot intermediate. J. Photonics Energy 2018, 8, 022008. 10.1117/1.jpe.8.022008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pun A. B.; Asadpoordarvish A.; Kumarasamy E.; Tayebjee M. J. Y.; Niesner D.; McCamey D. R.; Sanders S. N.; Campos L. M.; Sfeir M. Y. Ultra-fast intramolecular singlet fission to persistent multiexcitons by molecular design. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 821–828. 10.1038/s41557-019-0297-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins M. I.; McCamey D. R.; Tayebjee M. J. Y.. Fluctuating exchange interactions enable quintet multiexciton formation in singlet fission. 2019, arXiv:1906.08921v2. https://arxiv.org:1906.08921.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang H.; Zhao E.; Lam J. W. Y.; Tang B. Z. AIE luminogens: emission brightened by aggregation. Mater. Today 2015, 18, 365–377. 10.1016/j.mattod.2015.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Araki K.; Mutai T. Packing-directed tuning and switching of organic solid-state luminescence. Photochemistry 2016, 43, 191–225. 10.1039/9781782622772-00191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamse H.; Hamblin M. R. New photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 347–364. 10.1042/bj20150942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao L.; Song F.; Cui J.; Peng X. A near-infrared heptamethine aminocyanine dye with a long-lived excited triplet state for photodynamic therapy. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 9198–9201. 10.1039/c8cc04582h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski S.; Knap B.; Przystupski D.; Saczko J.; Kędzierska E.; Knap-Czop K.; Kotlińska J.; Michel O.; Kotowski K.; Kulbacka J. Photodynamic therapy - mechanisms, photosensitizers and combinations. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 106, 1098–1107. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malimonenko N.; Butenin A.; Mester I.; Kogan B. Nonlinear photodynamic therapy using saturation of the photosensitizer triplet states. Laser Phys. Lett. 2019, 16, 055602. 10.1088/1612-202x/ab0a5b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.; Zhou L.; Wei F.; Li L.; Zhao S.; Gong P.; Cai L.; Wong K. M.-C. Versatile Strategy To Generate a Rhodamine Triplet State as Mitochondria-Targeting Visible-Light Photosensitizers for Efficient Photodynamic Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 8797–8806. 10.1021/acsami.8b20224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pownall H. J. Solvent and substituent effects in aromatic carbonyl compounds: The triplet state of flavone. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 1974, 30, 953–959. 10.1016/0584-8539(74)80011-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruud K.; Schimmelpfennig B.; Ågren H. Internal and external heavy-atom effects on phosphorescence radiative lifetimes calculated using a mean-field spin–orbit Hamiltonian. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999, 310, 215–221. 10.1016/s0009-2614(99)00712-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wehry E. L.; Rogers L. B. Application of Linear Free Energy Relations to. Electronically. Excited States of Monosubstituted Phenols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 4234–4238. 10.1021/ja00947a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Favaro G. Substituent effect on triplet lifetimes of arylketones in benzene solution. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1973, 21, 401–405. 10.1016/0009-2614(73)80166-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y.; Nishimura H.; Umehara Y.; Yamada Y.; Tone M.; Matsuura T. Intramolecular Hydrogen Abstraction from Triplet States of 2,4,6-Triisopropylbenzophenones: Importance of Hindered Rotation in Excited States. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 1590–1597. 10.1021/ja00344a029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis F. D.; Hoyle C. H.; Magyar J. G.; Heine H. G.; Hartmann W. Substituent effects on the photochemical α-cleavage of deoxybenzoin. J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 488–492. 10.1021/jo00892a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stenberg V. I.; Singh S. P.; Kothari P. J. Excited State Theory: Monosubstituted Benzenes Fluorescence and Phosphorescence. Spectrosc. Lett. 1978, 11, 731–745. 10.1080/00387017808065110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirauchi K.; Amano T. Studies on the Phosphorimetric Determination of Amines with Halonitro Compounds. II. Substituent Effect on the Fluorescence and Phosphorescence of 4’-Substituted 4-Nitrodiphenylamines and 2-(Substituted Anilino)-5-nitropyridines. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1979, 27, 1120–1124. 10.1248/cpb.27.1120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima R.; Sakai K. Specific Photoreactions of Flavanones Typical of n,π* and π,π* Characters in Lowest Triplet States. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1986, 1217–1222. 10.1039/p29860001217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z.-P.; Aue W. A. Triplet-state energies and substituent effects of excited aroyl compounds in the gas phase. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2000, 56, 111–117. 10.1016/S1386-1425(99)00122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. W.; Pan D.; Shoute L. C. T.; Phillips D. L. Transient resonance Raman spectroscopic and ab initio MO investigation of substituent effects on the T1 triplet states of halobiphenyls. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2001, 32, 461–470. 10.1002/jrs.720. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D. Y.; Hrovat D. A.; Abe M.; Borden W. T. DFT Calculations on the Effects of Para Substituents on the Energy Differences between Singlet and Triplet States of 2,2-Difluoro-1,3-diphenylcyclopentane-1,3-diyls. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 12823–12828. 10.1021/ja0355067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togashi D. M.; Nicodem D. E. Photophysical studies of 9,10-phenanthrenequinones. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2004, 60, 3205–3212. 10.1016/j.saa.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto M.; Cai X.; Hara M.; Fujitsuka M.; Majima T. Significant effects of substituents on substituted naphthalenes in the higher triplet excited state. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 4657–4661. 10.1021/jp045608z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malval J.-P.; Dietlin C.; Allonas X.; Fouassier J.-P. Sterically tuned photoreactivity of an aromatic α-diketone family. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2007, 192, 66–73. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2007.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haley J. E.; Krein D. M.; Monahan J. L.; Burke A. R.; McLean D. G.; Slagle J. E.; Fratini A.; Cooper T. M. Photophysical properties of a series of electron-donating and -withdrawing platinum acetylide two-photon chromophores. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 265–273. 10.1021/jp104596v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahumada M.; Lissi E.; Calderón C. Anomalous Hammett’s plot in the quenching of Ru(bpy)32+ phosphorescence by p-substituted phenols. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2016, 325, 9–12. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2016.03.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll E. W.; Hunt J. R.; Dawlaty J. M. Proton Capture Dynamics in Quinoline Photobases: Substituent Effect and Involvement of Triplet States. J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 121, 7099–7107. 10.1021/acs.jpca.7b04512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanoë P.-H.; Moreno-Betancourt A.; Wilson L.; Philouze C.; Monnereau C.; Jamet H.; Jouvenot D.; Loiseau F. Neutral heteroleptic cyclometallated Platinum(II) complexes featuring 2-phenylbenzimidazole ligand as bright emitters in solid state and in solution. Dyes Pigm. 2019, 162, 967–977. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2018.11.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao C.; Chen G.; Yin Z. Excited-State Substituent Constants σCCex from Substituted Benzenes. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2008, 21, 808–815. 10.1002/poc.1387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G.-f.; Cao C.-z. Effect of Excited-State Substituent Constant on the UV Spectra of 1,4-Disubstituted Benzenes. Chin. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 22, 366–370. 10.1088/1674-0068/22/04/366-370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G.; Cao C. Substituent Effect on the UV Spectra of p-Disubstituted Compounds XPh(CH= CHPh)nY (n = 0, 1, 2). J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2010, 23, 776–782. 10.1002/poc.1660. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan H.; Cao C.-T.; Cao Z.; Chen C.-N.; Cao C. The Influence of the Excited-State Substituent Effect on the Reduction Potentials of Schiff Bases. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2016, 29, 145–151. 10.1002/poc.3511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q.; Cao C.-T.; Cao C.-Z. Extension and Application of Excited-State Constants of meta-Substituents. Wuli Huaxue Xuebao 2017, 33, 729–735. 10.3866/PKU.WHXB201611291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao C. T.; Yuan H.; Zhu Q.; Cao C. Determining the excited-state substituent constants σCC(o)ex of ortho-substituents from 2,4’-disubstituted stilbenes. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2019, 32, e3962 10.1002/poc.3962. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao C.; Sheng B.; Chen G. Determining the excited-state substituent constants σCCex of meta-substituent from 3,4’-disubstituted stilbenes. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2012, 25, 1315–1320. 10.1002/poc.3026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qu J.; Cao C.-T.; Cao C. Determining the excited-state substituent constants of furyl and thienyl groups. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2018, 31, e3799 10.1002/poc.3799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadlej-Sosnowska N.; Kijak M. Excited State Substituent Constants: To Hammett or Not?. Struct. Chem. 2012, 23, 359–365. 10.1007/s11224-011-9878-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrowolski J. C.; Lipiński P. F. J.; Karpińska G. Substituent Effect in the First Excited Singlet State of Monosubstituted Benzenes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 122, 4609–4621. 10.1021/acs.jpca.8b02209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozimiński W. P.; Dobrowolski J. C. σ- and π-electron contributions to the substituent effect: natural population analysis. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2009, 22, 769–778. 10.1002/poc.1530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek A.; Dobrowolski J. C. Heteroatom Incorporation Effect in σ- and π-Electron Systems: The sEDA(II) and pEDA(II) Descriptors. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 2608–2618. 10.1021/jo202542e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek A.; Dobrowolski J. C. The sEDA(=) and pEDA(=) Descriptors of the Double Bonded Substituent Effect. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 2997–3013. 10.1039/c3ob00017f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek A.; Dobrowolski J. C. On the Incorporation Effect of the Ring-Junction Heteroatom. The sEDA(III) and pEDA(III) Descriptors. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2015, 28, 290–297. 10.1002/poc.3409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glendening E. D.; Landis C. R.; Weinhold F. Natural Bond Orbital Methods. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 1–42. 10.1002/wcms.51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen R.; Baerends E. J. Exchange-correlation potential with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A 1994, 49, 2421–2431. 10.1103/physreva.49.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritsenko O. V.; Baerends E. J. The spin-unrestricted molecular Kohn–Sham solution and the analogue of Koopmans’s theorem for open-shell molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 8364–8372. 10.1063/1.1698561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank I.; Hutter J.; Marx D.; Parrinello M. Molecular dynamics in low-spin excited states. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 108, 4060–4069. 10.1063/1.475804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Filatov M.; Shaik S. Application of spin-restricted open-shell Kohn–Sham method to atomic and molecular multiplet states. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 116–125. 10.1063/1.477941. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S. Semiempirical GGA-Type Density Functional Constructed with a Long-Range Dispersion Correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2006, 27, 1787–1799. 10.1002/jcc.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall R. A.; Dunning T. H.; Harrison R. J. Electron affinities of the first-row atoms revisited. Systematic basis sets and wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 96, 6796–6806. 10.1063/1.462569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woon D. E.; Dunning T. H. Gaussian Basis Sets for Use in Correlated Molecular Calculations. III. The Atoms Aluminum through Argon. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 1358–1371. 10.1063/1.464303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Mennucci B.; Petersson G. A.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision D.01; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2013.

- SigmaPlot 13; Systat Software, 2017.

- Sinnecker S.; Neese F. Spin-spin contributions to the zero-field splitting tensor in organic triplets, carbenes and biradicals-a density functional and ab initio study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 12267–12275. 10.1021/jp0643303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn C. H.; Dongwook Kim D. A Comparison of the Density Functional Theory Based Methodologies for the Triplet Excited State of π-Conjugated Molecules: Time-Dependent DFT (TD-DFT), TD-DFT within Tamm-Dancoff Approximation (TDA-DFT), and Spin-Unrestricted DFT (UDFT). J. Korean Chem. Soc. 2019, 63, 73–77. 10.5012/jkcs.2019.63.2.73. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chai J.-D.; Head-Gordon M. Long-Range Corrected Double-Hybrid Density Functionals. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 131, 174105. 10.1063/1.3244209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou Q.; Subotnik J. E. Electronic Relaxation in Benzaldehyde Evaluated via TD-DFT and Localized Diabatization: Intersystem Crossings, Conical Intersections, and Phosphorescence. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 19839–19849. 10.1021/jp405574q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chai J.-D.; Head-Gordon M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom–atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. 10.1039/b810189b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemin D.; Perpète E. A.; Ciofini I.; Adamo C. Assessment of the ωB97 family for excited-state calculations. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2011, 128, 127–136. 10.1007/s00214-010-0783-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kruszewski J.; Krygowski T. M. Definition of aromaticity basing on the harmonic oscillator model. Tetrahedron Lett. 1972, 13, 3839–3842. 10.1016/s0040-4039(01)94175-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krygowski T. M.; Szatylowicz H.; Stasyuk O. A.; Dominikowska J.; Palusiak M. Aromaticity from the Viewpoint of Molecular Geometry: Application to Planar Systems. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 6383–6422. 10.1021/cr400252h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyrański M. K. Energetic Aspects of Cyclic Pi-Electron Delocalization: Evaluation of the Methods of Estimating Aromatic Stabilization Energies. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3773–3811. 10.1021/cr0300845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski S.; Dobrowolski J. C. What does the HOMA index really measure?. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 44158–44161. 10.1039/c4ra06652a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrowolski J. C.; Ostrowski S. On the HOMA index of some acyclic and conducting systems. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 9467–9471. 10.1039/c4ra15311a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrowolski J. C. Three Queries about the HOMA Aromaticity Index. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 18699–18710. 10.1021/acsomega.9b02628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadlej-Sosnowska N. Electronic properties and aromaticity of substituted diphenylfulvenes in the ground ( S0) and excited (T1) states. Struct. Chem. 2018, 29, 23–31. 10.1007/s11224-017-0995-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baird N. C. Quantum Organic Photochemistry. II. Resonance and Aromaticity in the Lowest 3ππ* State of Cyclic Hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94, 4941–4948. 10.1021/ja00769a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ottosson H. Organic photochemistry: Exciting excited-state aromaticity. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 969–971. 10.1038/nchem.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadakis R.; Ottosson H. The excited state antiaromatic benzene ring: a molecular Mr Hyde?. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 6472–6493. 10.1039/c5cs00057b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranac-Stojanović M. Triplet-State Structures, Energies, and Antiaromaticity of BN Analogues of Benzene and Their Benzo-Fused Derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 13582–13594. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b01858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui G.; Lu Y.; Thiel W. Electronic Excitation Energies, Three-State Intersections, and Photodissociation Mechanisms of Benzaldehyde and Acetophenone. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2012, 537, 21–26. 10.1016/j.cplett.2012.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takezaki M.; Hirota N.; Terazima M.; Sato H.; Nakajima T.; Kato S. Geometries and Energies of Nitrobenzene Studied by CAS-SCF Calculations. J. Phys. Chem. A 1997, 101, 5190–5195. 10.1021/jp970937v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giussani A.; Worth G. A. Insights into the Complex Photophysics and Photochemistry of the Simplest Nitroaromatic Compound: A CASPT2//CASSCF Study on Nitrobenzene. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017, 13, 2777–2788. 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b01149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda R.; Ehara M. Electronic excited states and electronic spectra of biphenyl: a study using many-body wavefunction methods and density functional theories. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 17426–17434. 10.1039/c3cp52636d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koseki S.; Toyota A. Energy Component Analysis of the Pseudo-Jahn-Teller Effect in the Ground and Electronically Excited States of the Cyclic Conjugated Hydrocarbons: Cyclobutadiene, Benzene, and Cyclooctatetraene. J. Phys. Chem. A 1997, 101, 5712–5718. 10.1021/jp970615r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feixas F.; Matito E.; Poater J.; Solà M. On the performance of some aromaticity indices: a critical assessment using a test set. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1543–1554. 10.1002/jcc.20914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gastel M. Zero-Field Splitting of the Lowest Excited Triplet States of C60 and C70 and Benzene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 10864–10870. 10.1021/jp105907e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feixas F.; Vandenbussche J.; Bultinck P.; Matito E.; Solà M. Electron delocalization and aromaticity in low-lying excited states of archetypal organic compounds. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 20690–20703. 10.1039/c1cp22239b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P.; Bernales V.; Truhlar D. G.; Gagliardi L. Valence ππ* Excitations in Benzene Studied by Multiconfiguration Pair-Density Functional Theory. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 75–81. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.8b03277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krygowski T. M.; Ejsmont K.; Stepień B. T.; Cyrański M. K.; Poater J.; Solà M. Relation between the substituent effect and aromaticity. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 6634–6640. 10.1021/jo0492113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krygowski T.; Stępień B.; Cyrański M. How the Substituent Effect Influences π-Electron Delocalisation in the Ring of Reactants in the Reaction Defining the Hammett Substituent Constants σm and σp. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2005, 6, 45–51. 10.3390/i6010045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krygowski T. M.; Dobrowolski M. A.; Zborowski K.; Cyrański M. K. Relation between the substituent effect and aromaticity. Part II. The case ofmeta- andpara-homodisubstituted benzene derivatives. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2006, 19, 889–895. 10.1002/poc.1039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.