Abstract

The prevalence and consequences of central sleep apnea (CSA) in adults are not well described. By utilizing the large Veterans Health Administration (VHA) national administrative databases, we sought to determine the incidence, clinical correlates, and impact of CSA on healthcare utilization in Veterans. Analysis of a retrospective cohort of patients with sleep disorders was performed from outpatient visits and inpatient admissions from fiscal years 2006 through 2012. The CSA group, defined by International Classification of Diseases-9, was compared with a comparison group. The number of newly diagnosed CSA cases increased fivefold during this timeframe; however, the prevalence was highly variable depending on the VHA site. The important predictors of CSA were male gender (odds ratio [OR] = 2.31, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.94–2.76, p < 0.0001), heart failure (HF) (OR = 1.78, 95% CI: 1.64–1.92, p < 0.0001), atrial fibrillation (OR = 1.83, 95% CI: 1.69–2.00, p < 0.0001), pulmonary hypertension (OR = 1.38, 95% CI:1.19–1.59, p < 0.0001), stroke (OR = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.50–1.82, p < 0.0001), and chronic prescription opioid use (OR = 1.99, 95% CI: 1.87–2.13, p < 0.0001). Veterans with CSA were at an increased risk for hospital admissions related to cardiovascular disorders compared with the comparison group (incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 1.50, 95% CI: 1.16–1.95, p = 0.002). Additionally, the effect of prior HF on future admissions was greater in the CSA group (IRR: 4.78, 95% CI: 3.87–5.91, p < 0.0001) compared with the comparison group (IRR = 3.32, 95% CI: 3.18–3.47, p < 0.0001). Thus, CSA in veterans is associated with cardiovascular disorders, chronic prescription opioid use, and increased admissions related to the comorbid cardiovascular disorders. Furthermore, there is a need for standardization of diagnostics methods across the VHA to accurately diagnose CSA in high-risk populations.

Keywords: central sleep apnea, heart failure, prescription opioids, health care utilization, obstructive sleep apnea, cardiovascular morbidity, incidence, prevalence, hospital admission

Statement of Significance

This retrospective study describes for the first time, the distribution, risk factors, and clinical correlates of central sleep apnea (CSA) in a large administrative database of veterans. Comorbid cardiovascular disorders and chronic prescription opioid use are strongly associated with CSA. A novel finding was that CSA was associated with an increased risk for cardiac disease–related hospital admissions. A prior diagnosis of heart failure was further associated with an increased risk for admissions in patients with CSA, thus underscoring the need for aggressively identifying and managing CSA in high-risk populations. Although the large national database was the strength of the study, the limitations included potential inaccurate diagnostic coding, unavailability of opioid dosing, and inability to determine whether the patients had received therapy.

Introduction

A large body of literature elucidates the risk factors and consequences of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) [1–7]. However, very little has been reported on the prevalence and consequences of central sleep apnea (CSA) in adults. The prevalence of OSA is estimated to be very high in veterans, up to 60 per cent [8, 9], in contrast to 4%–9% in the general population [10, 11]. Conversely, CSA, which is characterized by respiratory pauses during sleep due to the absence of respiratory effort [12, 13], has a high prevalence only in specific populations with heart failure [14, 15], chronic opioid use [16], and in older adults [17, 18]. However, the impact of CSA on clinical outcomes has not been studied in large clinical populations. Additionally, the distribution and the clinical correlates of CSA in the veteran population remain unknown [19]. This poses a major gap in the literature, as the scarcity of clinical outcomes data prevents delineation and prioritization of care for patients with CSA.

Thus, we sought to investigate the clinical characteristics of CSA in a large cohort of patients in the Veteran health care system by studying the national Veterans Health Administration (VHA) outpatient and the inpatient administrative databases. Our objectives were as follows: to (1) assess the incidence and prevalence of CSA, (2) determine the comorbid medical conditions associated with CSA, and (3) determine the impact of CSA on healthcare utilization, particularly hospital admissions related to cardiovascular disorders in the veteran population.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board and Clinical Investigation Committees of Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and the Ann Arbor Human Research Department approved this project and the use of the national VHA administrative databases.

Design

This is a retrospective cohort of patients with sleep disorders. The cohort was defined using VHA Medical SAS Datasets for outpatient visits and inpatient admissions from fiscal years (FY) 2006 through 2012 (VHA fiscal year is from October–September). The outpatient database includes all outpatient visits at the VHA outpatient clinics (hospitals and Community-Based Outpatient Clinics [CBOCs]). Each outpatient record contains a primary diagnosis, up to nine additional secondary diagnoses, as well as current procedural technology (CPT) procedure codes. All diagnosis codes follow the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) coding system [20]. The inpatient database includes all inpatient admissions that occurred at VHA hospitals nationwide. Each inpatient record contains the primary diagnosis and up to 12 additional secondary diagnoses. We also used the inpatient encounters database, which contains records of outpatient encounters that occurred during a hospitalization. In addition to care received at VHA facilities, veterans may be eligible for benefits to receive care at non-VHA facilities. These data are recorded in the VHA Fee-basis database and includes diagnosis and procedure codes for both inpatient and outpatient care. Thus, we also included these databases because not all VHA clinics have sleep laboratories (lab) available for sleep testing, and in such cases, patients are referred to the private-sector sleep labs to undergo sleep studies. Given that opioids and sedatives have been associated with sleep-disordered breathing, opioid and sedative medication data from the Decision Support System (DSS), VHA outpatient pharmacy database containing medication name and days supply was also used to track patient medication use. Finally, we used the VHA’s Corporate Data Warehouse Vital Signs table to obtain information on patient height and weight.

Cohort

Our cohort included veteran patients with at least one sleep-related diagnosis from FY2006–FY2012 (Supplementary Table S1). We then divided this cohort into two distinct groups for comparison: (1) patients with CSA and (2) patients with other sleep disorders (comparison group). Additionally, we excluded patients from both cases and controls (comparison group) who did not have a sleep test.

CSA group

Any patient diagnosed with CSA during our study period was included in this group. CSA was defined using outpatient or inpatient diagnosis codes of 327.71, 327.27, or 786.04 (Cheyne–Stokes respiration [CSR]) [12, 20]. The date of the patient’s first CSA diagnosis was used as the index date for all analyses.

Comparison group

The comparison group included all other patients with a sleep-related diagnosis, inpatient or outpatient, excluding patients who were diagnosed with either CSA or OSA. Thus, our comparison group includes all VA patients who have a sleep-related diagnosis as well as a documented sleep test during our study period who do not have either CSA or OSA. We excluded patients with OSA from the comparison group to minimize potential biases with misdiagnoses or inaccurate coding of OSA as CSA and vice versa. The index date for the comparison group was the date of their first sleep-related diagnosis.

Covariates

Demographics, comorbid medical conditions, sleep tests, and medications were included as covariates in the regression models. All demographics, sleep tests conducted, comorbid medical disorders, and medications are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Comorbid conditions included hypertension, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, obesity, asthma, pulmonary hypertension, atrial fibrillation, other arrhythmias, and ischemic heart disease. All comorbid medical conditions were defined as any diagnosis in the year prior to the patient’s index date. We also used CPT codes (Supplementary Table S1) to assess the presence of polysomnography (PSG) and limited channel sleep tests (home sleep apnea testing, HSAT) to determine how often CSA diagnosis was accompanied by the appropriate testing procedure. We allowed for tests to be within ±1 year of the index sleep diagnosis in order to catch potential miscodings in the sleep lab data.

Table 1.

Comparison of patient demographics and sleep tests between patients with CSA vs. other sleep-related diagnoses with a documented sleep test

| Condition | CSA | Comparison group | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 6002) | (n = 291,241) | ||

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Age | 59.7 ± 12.1 | 54.2 ± 12.9 | <0.0001 |

| Age group | |||

| 18–29 | 77 (1.3%) | 13,769 (4.7%) | <0.0001 |

| 30–39 | 270 (4.5%) | 27,456 (9.4%) | |

| 40–49 | 725 (12.1%) | 53,776 (18.5%) | |

| 50–59 | 1752 (29.2%) | 86,174 (29.6%) | |

| 60–69 | 2010 (33.5%) | 81,465 (28.0%) | |

| 70–79 | 839 (14.0%) | 22,836 (7.8%) | |

| 80+ | 329 (5.5%) | 5,765 (2.0%) | |

| Obese (diagnosis) | 2443 (40.7%) | 101,388 (34.8%) | <0.0001 |

| BMI* | 32.7 ± 6.7 | 33.6 ± 6.6 | <0.0001 |

| Male | 5862 (97.7%) | 271,775 (93.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Race | |||

| White | 4198 (69.9%) | 185,784 (63.8%) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 970 (16.2%) | 50,976 (17.5%) | |

| Other/missing | 834 (13.9%) | 54,481 (18.7%) | |

| Sleep Test | |||

| PSG | 5,700 (95.0%) | 224,722 (77.2%) | <0.0001 |

| VHA | 4,523 (75.4%) | 168,833 (58.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Fee-basis | 1,568 (26.1%) | 64,792 (22.3%) | <0.0001 |

| LCS | 892 (14.9%) | 85,486 (29.4%) | <0.0001 |

| VHA | 855 (14.3%) | 75,446 (25.9%) | <0.0001 |

| Fee-basis | 44 (0.7%) | 10,364 (3.6%) | <0.0001 |

CSA = Central sleep apnea; LCS = Limited channel study or home sleep test; PSG = Polysomnography, includes in-lab diagnostic sleep; split-night sleep and positive airway pressure titration studies; VHA = Veterans health administration.

*BMI = Body mass index, available for about 96 per cent of patients.

Diagnosis of obesity is used in modeling instead of BMI due to missing data for BMI.

Table 2.

Comparison of patient comorbid medical disorders and medications between patients with CSA vs. other sleep-related diagnoses with a documented sleep test

| Condition | CSA | Comparison group | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 6,002) | (n = 291,241) | ||

| Comorbid medical disorders | |||

| Hypertension | 4346 (72.4%) | 177,153 (60.8%) | <0.0001 |

| Heart failure | 1416 (23.6%) | 24,037 (8.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2007 (33.4%) | 55,098 (18.9%) | <0.0001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 549 (9.2%) | 11,402 (3.9%) | <0.0001 |

| COPD | 1320 (22.0%) | 44,346 (15.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 2261 (37.7%) | 84,408 (29.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Asthma | 388 (6.5%) | 18,564 (6.4%) | 0.78 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 263 (4.4%) | 3782 (1.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Arrhythmia | 1155 (19.2%) | 21,373 (7.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 876 (14.6%) | 13,366 (4.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Medications taken in year prior | |||

| Chronic opioids* | 1475 (24.6%) | 35,192 (12.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Opioid count | 3.12 ± 5.44 | 1.44 ± 3.58 | <0.0001 |

| Opioid (30 day) count | 2.80 ± 5.80 | 1.18 ± 3.50 | <0.0001 |

| Chronic benzo use | 697 (11.6%) | 28,215 (9.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Benzo count | 1.11 ± 3.13 | 0.89 ± 2.87 | <0.0001 |

| Benzo (30 day) count | 1.04 ± 3.05 | 0.82 ± 2.64 | <0.0001 |

| Opioid and benzo | 748 (12.5%) | 23,076 (7.9%) | <0.0001 |

| Opioid and benzo (30 day) | 537 (9.0%) | 15,754 (5.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic nonbenzo use | 292 (4.9%) | 6817 (2.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Nonbenzo sedative | 0.43 ± 1.81 | 0.20 ± 1.21 | <0.0001 |

| Nonbenzo (30 day) sedative | 0.38 ± 1.71 | 0.18 ± 1.12 | <0.0001 |

Benzo benzodiazepine medications; Nonbenzo (NBZ) = nonbenzodiazepine benzodiazepine receptor agonists; COPD = Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PSG = Polysomnography study; LCS = Limited channel study (home sleep apnea testing).

*See text for definition of chronic medication use.

We included four medication classes: opioids, benzodiazepines, sedatives, and nonbenzodiazepine receptor agonists (NBZ) (Supplementary Table S1). For descriptive analyses, we calculated the number of prescription fills in each class during the prior year, as well as the number of fills where the days supply was greater than or equal to 30. For all adjusted analyses, we created a “chronic use” variable for each class that we defined as use of at least three prescription fills for at least 30 days in the prior year.

To estimate the actual prevalence of CSA, we used data from the VHA Support Service Center (VSSC) in order to determine the total number of patients that received care at each site by fiscal year. This was calculated as the number of unique patients at each facility each fiscal year. The number of patients at each site was then summed over all sites to calculate the total number of veterans receiving care at the VHA each FY. Actual prevalence was calculated as the number of CSA-diagnosed patients divided by the number of patients seen at each site as well as VHA wide. Incidence of CSA was calculated as the number of new CSA-diagnosed patients in the given FY divided by the number or patients seen in the VHA during that FY.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were utilized to describe the cohort characteristics (mean ± SD for continuous variables, frequency, and percentages for categorical variables). t-Tests and chi-square tests were performed to test for differences between the CSA and comparison group. Trends over time for sleep tests and new CSA diagnoses were displayed graphically. We then conducted a series of multivariable models to (1) examine factors associated with CSA diagnosis; (2) compare actual and expected CSA prevalence by site; (3) assess the impact of CSA diagnosis (vs. comparison group) on the number of cardiac disease–related hospitalizations after the index date. All models were adjusted for age, gender, hypertension, heart failure, ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease (stroke and transient ischemic attack), COPD, diabetes, obesity, asthma, pulmonary hypertension, atrial fibrillation, other arrhythmias, chronic opioid use, chronic benzodiazepine use, and chronic NBZ receptor agonist use. Diagnosis of obesity was used in modeling instead of body mass index (BMI) due to missing data for BMI. Final models contained all factors significantly associated with the outcome. We removed variables where issues of collinearity were present. Collinearity was determined by correlation coefficients and changes in β-coefficient values as additional factors were included in the model.

To evaluate factors associated with CSA diagnosis, we used multilevel logistic regression with random intercepts for each site, which allowed us to account for correlation among patients from the same site. The evaluation of CSA prevalence by site revealed marked differences in the number of CSA diagnoses at each site. To examine the potential causes of this phenomenon, we calculated the expected prevalence of CSA at each site using a logistic regression model to generate predicted probabilities for CSA, which were then summed for each site. In addition to the previously mentioned predictors, we also adjusted for the two types of sleep tests. This model did not account for correlation among patients within the same site as our aim was to estimate the expected prevalence assuming that all sites were the same (i.e. diagnosis patterns did not differ across sites). Graphical procedures were used to display expected versus actual prevalence of CSA by site. Finally, multilevel negative binomial regression was used to determine the impact of CSA on the number of future cardiac disease–related hospitalizations (i.e. admission with a primary diagnosis code of heart failure, ischemic heart disease, arrhythmia, or atrial fibrillation) following the diagnosis of CSA or following the diagnosis of other sleep diagnoses, for the CSA and comparison groups, respectively. Differential follow-up time was accounted for by use of an offset (i.e. regression coefficient set to (1) for the number of days from index to the end of the study period [or death]). The main predictor of interest was CSA (vs. comparison group) and in addition to the previously mentioned health factors, we also examined all pairwise interactions between CSA diagnosis and medical comorbidities. The final model contained all interactions that were statistically significant. All statistical tests were performed using α = 0.05. SAS V9.4 (Cary, NC) and Stata 14/MP (College Station, TX) were utilized for statistical analysis.

Sensitivity analyses were performed for both the multilevel logistic regression model with CSA as the outcome and the multilevel negative binomial model using future cardiac disease–related hospitalizations. The results from these models can be found in Supplementary Material. The models were run for the following cohorts of patients: current cohort of patients with OSA-diagnosed patients added back into the comparison group, cohort of patients that did not undergo a sleep test with OSA-diagnosed patients removed from the comparison group, and cohort of patients that did not require a sleep test with patients with OSA added back into the comparison group.

Results

CSA distribution

Our cohort originally included 1,336,873 patients from 130 VAMCs who were diagnosed with a sleep disorder between FY2006 and 2012. Of these, 8500 (0.6%) were also diagnosed with CSA, whereas in the comparison group, 1,328,373 (99%) had a nonsleep apnea sleep disorder. However, only 297,243 (22.2%) of these patients in either group had a sleep study leaving us with 6002 (2.0%) patients diagnosed with CSA and the remaining 291,241 (98%) in the comparison group. In addition, 3849/6002 (64.1%) of CSA group patients also had a diagnosis of OSA either at index date or in the year prior. The results presented below are from patients with documented sleep tests (n = 297,243), whereas results from the original cohort (n = 1,336,873) can be found in Supplementary Tables S4–S7.

Baseline characteristics of patients with CSA versus the comparison group are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Patients diagnosed with CSA were older, were more likely to be diagnosed as “obese,” and more likely to be male (p < 0.0001). The patients with CSA were also more likely to have several medical comorbidities. Notably, patients diagnosed with CSA were over three times more likely to have pulmonary hypertension (4.4% vs. 1.3%) and atrial fibrillation (14.6% vs. 4.6%) and nearly three times more likely to have heart failure (23.6% vs. 8.3%) and other arrhythmias (19.2% vs. 7.3%). Compared with the comparison group, patients with CSA were nearly twice as likely to have chronic prescription opioid use (24.6% vs. 12.1%) in the previous year and, on average, had 1.6 more 30 day opioid prescriptions in that year (2.80 vs. 1.18).

Based on CPT codes (Supplementary Table S1), 95 per cent of CSA-diagnosed patients underwent in-lab PSG testing within a year of their diagnosis, with 75.4 per cent tested at a VA sleep lab and 26.1 per cent outside the VA as a fee-basis visit. Approximately 15 per cent of patients with CSA had HSAT. The full array of sleep tests by study group can be found in Table 1.

Comorbid health factors associated with CSA diagnosis

We used a multilevel logistic regression model to examine factors associated with a CSA diagnosis (Table 3). Among the factors studied, two were associated with two times greater risk of CSA diagnosis: male gender (odds ratio [OR] = 2.31, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.94–2.76, p < 0.0001) and chronic opioid use (OR = 1.99, 95% CI: 1.87–2.13, p < 0.0001). Several other factors were associated with approximately 1.5 times greater risk of CSA diagnosis: pulmonary hypertension (OR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.19–1.59, p < 0.0001), atrial fibrillation (OR = 1.83, 95% CI: 1.69–2.00, p < 0.0001), other arrhythmias (OR = 1.49, 95% CI: 1.38–1.82, p < 0.0001), cerebrovascular disease (OR = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.50–1.82, p < 0.0001). Ischemic heart disease, obesity, and age were also associated with increased risk of CSA. Chronic use of benzodiazepine medications was associated with increased risk of CSA diagnosis in unadjusted models (OR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.11–1.31, p ≤ 0.0001), but due to collinearity with chronic opioids, this relationship reversed and therefore was not included in our final model (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multilevel logistic regression results: predictors of CSA diagnosis among VA patients with a documented sleep test (N = 297,243)

| Variable | OR | 95% C.I. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (5 year increase) | 1.13 | 1.11 | 1.14 | <0.0001 |

| Gender (male) | 2.31 | 1.94 | 2.76 | <0.0001 |

| Heart failure | 1.78 | 1.64 | 1.92 | <0.0001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1.17 | 1.10 | 1.25 | <0.0001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.65 | 1.50 | 1.82 | <0.0001 |

| Obese | 1.11 | 1.05 | 1.17 | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1.38 | 1.19 | 1.59 | <0.0001 |

| Arrhythmia | 1.49 | 1.38 | 1.82 | <0.0001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.83 | 1.69 | 2.00 | <0.0001 |

| Chronic opioids | 1.99 | 1.87 | 2.13 | <0.0001 |

| Chronic nonbenzo | 2.22 | 1.95 | 2.53 | <0.0001 |

The results presented in the table represent the final regression model.

For the reasons noted earlier (see Methods), we also repeated all analyses with patients with a sleep test with the diagnosis of OSA included in the comparison group and found that the results were similar except that the odd ratios for a few of the comorbid factors were somewhat attenuated (pulmonary hypertension and atrial fibrillation) and obesity was no longer a significant predictor (Supplementary Table S2).

Actual vs. expected CSA prevalence

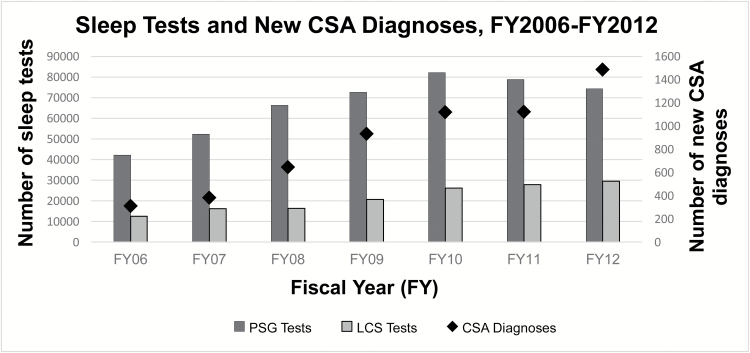

The overall prevalence of CSA across all VA sites was 0.096 per cent in FY 2012. There was a statistically significant increase in incidence of the diagnosis of CSA over the 7 years included in this study and the trend for increase over time was significant, p < 0.0001 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trends over time (FY 2006 to FY 2012) for all in-lab PSG and limited channel (LCS) sleep tests as well as new CSA diagnoses. The dark grey bars represent in-lab sleep studies, including diagnostic, split-night and PAP titration studies. The light grey bars present LCS or home sleep tests and the black diamond represents the number of new CSA diagnoses. All three parameters increased significantly over time (p for trend < 0.0001).

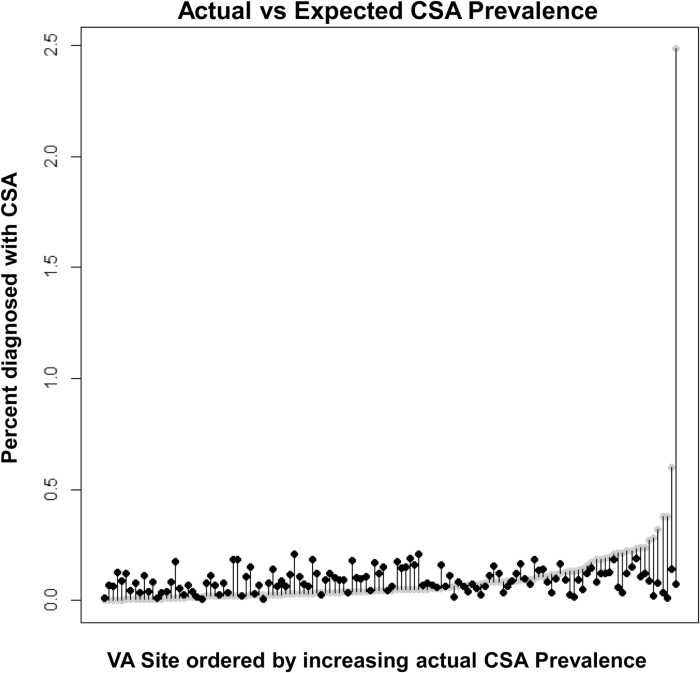

The distribution of CSA-diagnosed patients was highly variable across the 130 included VA facilities with a minimum of 0 diagnosed patient and a maximum of 1062 diagnosed patients. Given this unexpected distribution of CSA-diagnosed patients, we calculated a patient-level, factor adjusted expected count of CSA diagnoses for each site via logistic regression. These results revealed a more uniform expected distribution across the sites (minimum = 0.6, maximum = 206). The site with the highest actual CSA diagnosis count (1062 patients) was only expected to have 88 diagnosed patients (8.3% of their actual count).

After accounting for the total number of patients receiving care at each site using the VSSC data, the actual prevalence of CSA across VHA facilities ranged from 0 to 2.5 per cent. Our adjusted analysis resulted in expected prevalence ranging from 0.005 to 0.21 per cent. A comparison of actual prevalence versus the expected prevalence is shown in Figure 2. In this figure, the gray points represent each site’s actual prevalence, whereas the black points represent the expected prevalence. The largest differences are noted on the far right of the figure where the facilities have far greater prevalence of CSA than expected.

Figure 2.

Comparison of predicted and actual CSA prevalence by site demonstrates the prevalence of CSA calculated as the number of CSA diagnoses per average number of patients seen at each site during FY 2006–2012. Data on the x-axis represent VA sites ordered with increasing actual prevalence. Data on the y-axis represent actual and predicted CSA prevalence; grey circles represent the actual prevalence and black circles represent the predicted prevalence. Note that the largest differences are on the far right of the figure where the facilities have far greater prevalence of CSA than expected.

Hospital admissions related to cardiac disorders following initial CSA diagnosis

Future admissions due to cardiac disorders (heart failure, ischemic heart disease, arrhythmia, or atrial fibrillation) were observed in 6.6 per cent of all patients evaluated during the study period. However, among CSA-diagnosed patients, admissions due to cardiac disorders increased to 10.6 per cent. CSA-diagnosed patients averaged nearly two times greater number of admissions than the comparison group patients (0.22 vs. 0.12). After adjusting for other health factors (Table 4), CSA diagnosis remained associated with increased risk of future cardiac disease–related hospitalizations (incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 1.50, 95% CI: 1.16–1.95, p = 0.002). There were three significant interactions with CSA diagnosis: hypertension, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation. All three of these comorbidities were associated with significant increases in future cardiac admissions among the comparison group patients (IRR = 1.57, 95% CI: 1.51–1.64, p < 0.0001; IRR = 3.32, 95% CI: 3.18–3.47, p < 0.0001; IRR = 2.30, 95% CI: 2.18–2.44, p < 0.0001, respectively). Among the patients with CSA, hypertension was no longer significant (IRR = 1.09, 95% CI: 0.83–1.42, p = 0.55), atrial fibrillation was associated with increased risk, but this risk was attenuated (IRR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.21–1.97, p < 0.0001), and heart failure was associated with even greater risk of future admissions (IRR = 4.78, 95% CI: 3.87–5.91, p < 0.0001). These results indicate that not only is CSA independently associated with future hospital admissions, but it also modifies the risk due to other important comorbidities. Additionally, the presence of concomitant OSA did not increase the risk for future cardiac disease–related admissions among patients with CSA (IRR 0.82, 95% CI: 0.66–1.03, p = 0.09). Finally, all comorbidities in our final model were associated with increased risk of future cardiac disease–related admissions, with male gender, ischemic heart disease, diabetes, pulmonary hypertension, and other arrhythmias associated with at least 1.5 times increased risk of future cardiac admissions (Table 4). Similar results were also noted when studying effects of CSA diagnosis on hospital admissions in patients who underwent a sleep test but with patients with OSA included in the comparison group (Supplementary Table S3).

Table 4.

Multilevel regression results: predictors of cardiac disease–related admissions after index diagnosis among patients with a documented sleep test (N = 297,243)

| Variable | IRR | 95% C.I. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (5 year increase) | 1.12 | 1.11 | 1.13 | <0.0001 |

| Gender (male) | 1.90 | 1.72 | 2.09 | <0.0001 |

| CSA | 1.50 | 1.16 | 1.95 | 0.002 |

| Hypertension | 1.57 | 1.51 | 1.64 | <0.0001 |

| Heart failure | 3.32 | 3.18 | 3.47 | <0.0001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2.69 | 2.60 | 2.79 | <0.0001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.20 | 1.12 | 1.28 | <0.0001 |

| COPD | 1.37 | 1.32 | 1.43 | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 1.74 | 1.68 | 1.80 | <0.0001 |

| Obese | 1.15 | 1.11 | 1.19 | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1.52 | 1.38 | 1.68 | <0.0001 |

| Arrhythmia | 1.62 | 1.55 | 1.71 | <0.0001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.30 | 2.18 | 2.44 | <0.0001 |

| Chronic opioids | 1.17 | 1.12 | 1.22 | <0.0001 |

| CSA* hypertension | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.90 | 0.01 |

| CSA* heart failure | 1.44 | 1.16 | 1.79 | 0.001 |

| CSA* atrial fibrillation | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.86 | 0.002 |

CSA = Central sleep apnea; COPD = Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IRR = Incidence rate ratio.

*Indicates interaction between CSA and the associated comorbid condition.

The results presented in the table represent the final regression model.

Discussion

This study describes for the first time, the distribution, risk factors for and clinical correlates of CSA in the US veteran population. Our review of the national VHA administrative databases revealed that (1) the incidence (new cases) of CSA diagnosis in US veterans increased approximately fivefold over a period of 7 years; (2) there was considerable variability in the prevalence of CSA across different VA medical centers; we speculate that this may be potentially related to variability in diagnostic methodology and in ICD coding; (3) among veterans with sleep disorders who had undergone a sleep test, the important predictors of CSA were heart failure, atrial fibrillation, other arrhythmias, pulmonary hypertension, stroke, and chronic prescription opioid use; and (4) veterans with CSA were at an increased risk for hospital admissions related to cardiac diseases (heart failure, stroke, arrhythmias) compared with patients with non-sleep apnea sleep disorders. (5) Analyses also showed that among patients with CSA, presence of heart failure (HF) was associated with an even higher risk of future admissions compared with patients without CSA.

Prevalence and distribution of CSA in veterans

Although this study relied solely on administrative data in veterans, the results do provide an overall pattern of CSA in the US veteran population. Our findings corroborate large cross-sectional epidemiological studies demonstrating higher prevalence of CSA among men, older adults [17, 18]. However, no prior studies have demonstrated the increasing incidence of CSA in a specific population. We observed that over a period of 7 years, there was an increasing number of new cases of CSA (p < 0.0001). This trend could be related to various reasons, including growing familiarity with the ICD-9 code for CSA which was introduced in 2006, true increase in CSA incidence, and an increase in the number of diagnostic sleep studies (Figure 1).

There was also a wide variation in the prevalence of CSA diagnosis among the different Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (VAMCs) across the nation. Our model fit to calculate expected prevalence by site showed that even after accounting for important patient characteristics (demographics, comorbidities, sleep tests, medications), the distribution of CSA diagnosis across the VAMCs greatly differed from what was expected. This suggests that there are unobserved differences between the VAMCs that are driving the variation in the diagnosis of CSA. Potential sources of this unexplained variation include differences in the use of diagnostic thresholds, tools, and definitions for CSA and differences in coding patterns. The inaccurate characterization of patients in a VA clinical database has been described in prior studies. For example, it has been previously demonstrated that only half of patients in a VA cohort labeled as having COPD actually had airflow obstruction on spirometry [21]. In contrast, our study cohort only included patients who had a documented sleep study, decreasing the likelihood CSA was diagnosed empirically. Sleep lab diagnostic testing practices need to be reviewed in detail to examine the potential sources of variation in the occurrences of CSA across the different VAMC sleep labs. Only a few VAMC sleep labs in the United States are accredited by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM). Even in 2012, an inventory of VA sleep medicine programs demonstrated considerable variability in the types of sleep services offered; only 28 per cent of VA sites provided the whole gamut of sleep services, whereas 46 per cent were “intermediate” programs and 17 per cent did not offer any formal sleep services [22].

Notably, the overall low prevalence of CSA in our cohort compared with a prevalence of 0.4 per cent in a prospective population-based sample [17] may suggest that there is under-diagnosis of CSA in the VHA population. The reason for the overall lower prevalence in this VHA sample cannot be ascertained from our study. The diagnosis of CSA requires the presence of at least five central apneas or central hypopnea events per hour that comprise 50 per cent of all respiratory events for that study night [13]. Thus, a sleep study, preferably an in-lab attended full night or a split night PSG study, is required to make the diagnosis [23]. A technically adequate HSAT [23] can also detect the presence of CSA; however, a HSAT that is negative for CSA does not reliably confirm the absence of CSA. Given that access to in-lab sleep studies has been limited in the VAMCs, it is very likely that CSA may have remained under diagnosed following a negative HSAT. Moreover, the classification of central vs. obstructive hypopneas remains ambiguous even when using standard methodologies [24] and given that most labs do not routinely use an esophageal catheter, the central apnea index is likely underestimated in clinical sleep studies. We speculate that the above reasons may have contributed to the variable and lower estimates of prevalence from the VHA databases. Hence, we recommend the use of uniform definitions and testing methods to enhance the accuracy and detection of CSA in the veteran population.

Comorbid medical disorders and prescription opioid use

Our findings affirm results from prior studies in from smaller clinical populations that have noted increased risk of CSA in the presence of heart failure [14, 25], atrial fibrillation, other arrhythmias [14], stroke [26], and chronic opioid use [16, 27]. Veterans with CSA were obese. Increased risk of CSA among obese individuals may reflect the presence of OSA or heart disease in this group. We also observed that majority (64.1%) of the CSA group patients had comorbid OSA. This corroborates our findings from a previous smaller study from our sleep lab [28]. The presence of concomitant OSA in patients with CSA highlights the pathophysiological link between central and obstructive apnea. Specifically, patients with OSA demonstrate increased propensity to central apnea [29], which is reversible with the use of nasal CPAP. Thus, increased central apnea propensity may be due to chronic intermittent hypoxia and ensuing increase in chemoreflex sensitivity [29, 30]. Likewise, pharyngeal narrowing or occlusion during episodes of central apnea may be a precursor for OSA [31]. The aforementioned observations may provide a physiological explanation for the benefit of nasal CPAP in treating central apnea in over half of the patients with CSA [28]. However, additional analyses showed largely similar associations with OSA included in the comparison group (Supplementary Material) as well as in the CSA group with CSA and concomitant OSA diagnoses. OSA also did not significantly increase the risk of cardiac-related admissions among patients with CSA (IRR = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.66–1.03, p = 0.09).

The use of chronic prescription opioids for pain [32] and increased mortality related to their use are serious problems in the veteran population [33]. We noted that the percentage of patients chronically using prescription opioid drugs in the CSA population was significantly higher than the comparison group, with 24.6 per cent of patients with CSA found to be chronic opioid users compared with 12.1 per cent in the comparison group. In small retrospective sleep clinic–based studies, CSA was present in 25%–30% of patients on chronic opioids vs. only 5 per cent of patients not on chronic opioids [16] with a dose-dependent relationship between the morphine dose and severity of sleep apnea [27]. Although CSA has been reported even at lower doses of opioid medications with a wide dose range of effect on central apneas [27], unfortunately, our study did not evaluate the exact prescription opioid doses dispensed to the CSA population and may have underestimated the prevalence of CSA in chronic opioid users due to the lack of recognition and testing. Moreover, due to the cross-sectional nature of the analyses, our study did not evaluate the impact of opioid dose on the risk for developing incident CSA. Conversely, selection bias may lead to overestimation of the prevalence of CSA among chronic opioid users in studies that demonstrated a very high prevalence of CSA. Other differences from other studies may have been in the definition of “chronic opioid” use or the absence of a threshold dose of chronic opioids that may pose as a risk factor for the development of CSA. Future studies need to determine the risk for opioid-induced CSA and the impact of opioid dose on clinical consequences in the veteran population.

Impact on healthcare utilization

Our study also revealed the important novel finding that veterans diagnosed with CSA also experienced increased risk of hospital admissions for cardiac disorders, including heart failure. Notably, although the presence of hypertension was also associated with an increased risk for hospital admissions in our comparison group, there was no additional risk for these patients in the CSA group. Conversely, the risk among heart failure patients appears to be much greater in patients with CSA compared with our comparison patients. This highlights the importance of properly diagnosing CSA as it is not only associated with increased future cardiac disease–related hospital admissions, but it also affects the associations of other important predictors of future admissions. This association cannot be ignored when caring for these high-risk patients. While a prior study reported an increased rate for heart failure–related readmissions in veterans with OSA, it had excluded patients with CSA [34]. Our data suggest that although CSA was associated with increased risk for admissions related to cardiovascular disease, the presence of comorbid OSA in the CSA group did not seem to enhance the risk. Whether these patients with CSA were adequately titrated with positive airway pressure therapy (PAP) for CSA could not be determined from our review of the database. Moreover, whether the increased hospitalization risk is due to untreated CSA per se or whether it indicates the severity of underlying comorbid conditions or both cannot be determined from our database analyses. However, the results identify a high-risk veteran population group that may require heightened awareness of the respiratory effects of chronic heart failure or chronic opioid use and more careful management of the underlying disease conditions. Moreover, patients with cardiac disease and chronic opioid medication use should undergo an in-lab PSG study, if HSAT is negative for CSA. Our study results underscore the need for actively seeking and detecting CSA in high-risk populations. Thus, clinical pathways should incorporate CSA with heart failure as “high-risk” for probability for hospitalizations when designing disease management pathways.

Study limitations

The main strength of this study was the use of a large database that encompasses multiple regions of the country and includes a wide age range with multiple ethnicities and comorbidities. However, the potential limitations related to using administrative data are implicit to the current study results. These include inaccuracies of ICD-9 and CPT coding to make the sleep diagnoses and the absence of sleep tests in large portion of the original cohort. Hence, we narrowed our analyses only to the population that had undergone a sleep test based on the appropriate CPT code. Although diagnoses made using VHA administrative data seem to have good agreement (κ) with actual chart review [35], studies have also reported inaccurate characterization of patients in a VA clinical database. Moreover, the BMI data had inaccuracies due to missing data. Instead, we used obesity as a diagnosis rather than BMI in our models. Due to the male-predominant population of the VHA databases, the results may or may not be generalizable to the general population.

Additionally, due to the cross-sectional nature of the analyses, a causal relationship or the direction of association between CSA and comorbid conditions cannot be determined from this study. There may be potential residual confounding that may be unaccounted for in the regression models. Hence, only potential associations are implied from our analyses. For example, we were only able to identify admissions within the VHA, as the database does not store information regarding hospital admissions not paid for by the VHA. Additionally, we did not have opioid medication dosing information available to us for these analyses, but acknowledge that dose may play an important role in our findings related to opioids. We also did not have access to outside (non-VA) medication data, which could lead us to underestimating the medication use in our cohort. Finally, analyses of administrative databases did not allow us to determine whether the patients had received therapy for CSA or whether they were adherent to PAP or oxygen therapy for CSA or not. However, irrespective of the presence or absence of therapy, CSA appeared to confer an overall increased risk for hospital admissions related to cardiac diseases.

Significance and Relevance to Veteran Care

For the first time, this observational study provides an estimate of the new cases of CSA, and the prevalence and clinical correlates of CSA in a very large national database. Most importantly, our analyses suggest that there is increased healthcare utilization, in terms of increased cardiac disease–related hospitalizations in association with CSA. The wide variability of actual prevalence of CSA between the VA medical sites highlights the need for standardization of in-lab PSGs using AASM-established criteria for the diagnosis of CSA and OSA [13, 23] in patients at high risk for CSA and for cardiovascular disease–related hospitalizations.

Arguably, there is a need for establishing a prospective longitudinal cohort of veterans with sleep apnea that will determine whether there is a causal relationship between CSA and adverse health outcomes, including increased cardiovascular events and mortality and poor quality of life. Future studies should also evaluate whether or not there is effect modification on outcomes and mortality based on adequate PAP adherence or other therapies (e.g. supplemental oxygen) for CSA [28]. We anticipate that our study results will drive the development of risk-stratification models to lessen hospital-admissions in patients with CSA and eventually improve the overall health of veterans suffering from chronic diseases.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at SLEEP online.

Funding

Support for this work was provided by a Career Development Award-2 from the Department of Veterans Affairs (#CDA-2-019-07F, to S.C.) and the Metropolitan Detroit Research and Education Foundation.

Notes

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1. Nieto FJ, et al. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep Heart Health Study. JAMA. 2000;283(14):1829–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peppard PE, et al. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(19):1378–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marin JM, et al. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1046–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yaggi HK, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(19):2034–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Campos-Rodriguez F, et al. Cardiovascular mortality in women with obstructive sleep apnea with or without continuous positive airway pressure treatment: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(2):115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Martínez-García MA, et al. Cardiovascular mortality in obstructive sleep apnea in the elderly: role of long-term continuous positive airway pressure treatment: a prospective observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(9):909–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moon K, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and type 2 diabetes in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2015;31(1):139–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sharafkhaneh A, et al. Sleep apnea in a high risk population: a study of Veterans Health Administration beneficiaries. Sleep Med. 2004;5(4):345–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling elderly. Sleep. 1991;14(6):486–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Young T, et al. ; Sleep Heart Health Study Research Group. Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling adults: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(8):893–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peppard PE, et al. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(9):1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders 3rd Ed Darien, IL USA: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Berry et al. for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications, Version 2.4. www.aasmnet.org. Darien, Illinois: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Javaheri S, et al. Sleep apnea in 81 ambulatory male patients with stable heart failure. Types and their prevalences, consequences, and presentations. Circulation. 1998;97(21):2154–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Javaheri S. Central sleep apnea in congestive heart failure: prevalence, mechanisms, impact, and therapeutic options. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;26(1):44–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang D, et al. Central sleep apnea in stable methadone maintenance treatment patients. Chest. 2005;128(3):1348–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bixler EO, et al. Effects of age on sleep apnea in men: I. Prevalence and severity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(1):144–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hoch CC, et al. Comparison of sleep-disordered breathing among healthy elderly in the seventh, eighth, and ninth decades of life. Sleep. 1990;13(6):502–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jackson M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of sleep apnea among US male veterans, 2005-2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth revision, Clinical Modification: ICD-9-CM. Vol 4th ed Washington, DC, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Collins BF, et al. Factors predictive of airflow obstruction among veterans with presumed empirical diagnosis and treatment of COPD. Chest. 2015;147(2):369–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sarmiento K, et al. ; VA Sleep Network. The state of veterans affairs sleep medicine programs: 2012 inventory results. Sleep Breath. 2016;20(1):379–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kapur VK, et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(3):479–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pamidi S, et al. ; American Thoracic Society Ad Hoc Committee on Inspiratory Flow Limitation. An official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report: noninvasive identification of inspiratory flow limitation in sleep studies. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(7):1076–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Javaheri S, et al. ; Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study Research Group. Sleep-disordered breathing and incident heart failure in older men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(5):561–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Javaheri S, et al. Sleep apnea: types, mechanisms, and clinical cardiovascular consequences. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(7):841–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Walker JM, et al. Chronic opioid use is a risk factor for the development of central sleep apnea and ataxic breathing. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(5):455–461. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chowdhuri S, et al. Treatment of central sleep apnea in U.S. veterans. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8(5):555–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Salloum A, et al. Increased propensity for central apnea in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: effect of nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(2):189–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chowdhuri S, et al. Effect of episodic hypoxia on the susceptibility to hypocapnic central apnea during NREM sleep. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2010;108(2):369–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Badr MS, et al. Pharyngeal narrowing/occlusion during central sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1995;78(5): 1806–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lovejoy TI, et al. Correlates of prescription opioid therapy in Veterans with chronic pain and history of substance use disorder. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(1):25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bohnert AS, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1315–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sommerfeld A, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with increased readmission in heart failure patients. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40(10):873–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Borzecki AM, et al. Identifying hypertension-related comorbidities from administrative data: what’s the optimal approach?Am J Med Qual. 2004;19(5):201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.